Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 140

December 5, 2014

Prayer After Eric Garner

Nishmat Kol Chai / Breath of All Life:

Your breath enlivened the first man,

You breathe

the breath of life in each of us.

Today our breath is shortened

as we remember Eric Garner gasping

"I can't breathe," an elbow pressed

around his neck.

Breathe into us

determination to build a better world

where no innocent is killed

by those sworn to serve and protect.

Ignite us toward justice.

Eric Garner was made in Your image.

His six children, bereaved: in Your image.

Every Black man, woman, and child

twenty times likelier to be killed by police

than their white neighbors:

in Your image.

Help us to root out from every heart

the hidden prejudice

which causes police to open fire in fear,

which transforms a child in a hoodie

into a hoodlum, a person into a threat.

Comfort the families of all who grieve.

Strengthen us to work for a world redeemed.

And we say together: Amen.

Nishmat Kol Chai is a Hebrew name for God; it means "The Breath of All Life." It is also the name of a prayer which explores this theme, recited on Shabbat and festivals.

On "Your breath enlivened the first man," see Torah, Bereshit (Genesis) 2:7.

On "twenty times likelier to be killed by police / than their white neighbors, see Pro Publica's report Deadly force, in black and white.

For more on the connections between the Hebrew n'shima (breath) and neshama (soul), and how these relate to the death of Eric Garner, see Rabbi Pam Wax's post I Can't Breathe -- IMO Eric Garner.

Here's a statement from T'ruah: the Rabbinic Call for Human Rights on the death of Eric Garner and our justice system: Justice for Eric Garner.

December 4, 2014

Justice, justice shall you pursue

We have three-strikes laws for petty crimes but when the justice system fails over and over again nothing happens to change it.

— kaya oakes (@kayaoakes) December 3, 2014

I know that I do not understand the American legal system as well as I could. I know that I particularly don't have a nuanced understanding of grand juries and how they function. But even from my relatively inexpert standpoint I can tell that something is not working right in our justice system.

You probably know by now that a grand jury has decided not to charge the NYPD officer who choked Eric Garner to death. Apparently the officer thought he was selling loose cigarettes. Which he wasn't. But that's not the point. Eric gasped "I can't breathe" eleven times before he died.

Chokeholds, as it happens, are banned by NYPD's standards. Eric was unarmed when the officer choked him and killed him. The whole awful incident was caught on video tape. And now the grand jury has decided not to press charges against this officer who killed an innocent Black man.

If the case had gone to trial, prosecutors and defenders could have argued the facts of the case. But the grand jury's decision means it won't go to trial. Exactly like the recent grand jury decision which means that officer Darren Wilson won't be tried for the killing of Michael Brown, either.

These are not separate tragedies. This is a pattern. Wake up, white America. #EricGarner #BlackLivesMatter #Ferguson #MikeBrown #solidarity

— Ayesha Mattu (@Ayesha_Mattu) December 3, 2014

What message can this grand jury decision possbibly send to Americans of color? Judging by the Black voices in my Twitter stream, what it says is that Black lives are insignificant. How else to interpret the reality that someone who kills a Black man in full view of the public isn't even brought to trial?

Congressional Black Caucus "this nation seems to have heard one message loud & clear: there'll be no accountability for taking Black lives"

— Ayman Mohyeldin (@AymanM) December 3, 2014

People of color do not feel safe in this country, and I can understand why not. Don't believe me? Read about how Black moms have to have "The Talk" with their kids -- about how to appear unthreatening, and accept humiliation as necessary, in order to not be killed by trigger-happy fearful white people.

It is terrible enough that people live in fear of their children being mistreated, humiliated, or killed because of the color of their skin -- because a Black teenager (even in his own home!) might be mistaken for a criminal, or if he reaches for a bag of skittles he might be "reaching for a gun."

It is so much worse that people live in fear of the police and the legal system which are supposed to protect us from precisely that kind of prejudice and injustice. Cops are supposed to keep us safe. The legal system is supposed to be righteous and just. And right now those seem to be questionable.

2. Almost every blk person in the US feels under siege right now. That system design to protect us might in fact kill us, & get away with it

— Joshua DuBois (@joshuadubois) December 3, 2014

This isn't just about officer Daniel Pantaleo and the fact that he will not see trial. It's about the fact that white people and people of color experience different systems of justice. It's about the shameful truth in W. Kamau Bell's On Being a Black Man, Six Feet Four Inches Tall, in America in 2014. (Read it -- the shame lies not in his fear of police, but in the fact that today's reality gives him reason to fear.)

I am holding the grieving family of Eric Garner in my prayers. And I am doing my best to listen to people of color in this country about the reality they inhabit, and to take their lead on working toward change. I do not want to live in a country where the following tweet seems so painfully true:

...With liberty and justice for some. #ICantBreathe

— Akilah Hughes (@AkilahObviously) December 3, 2014

December 3, 2014

In a time beyond time

Breath comes slow.

Behind the curtain

a gurgling: fish tank?

Medical equipment?

I don't part the veil.

Snatches of liturgy

wash over me and are gone.

My God, the soul You placed

in me is pure. Shelter

her beneath Your wings.

Now and forever.

Now is forever.

And when the soul is ready

to let go, tether trailing

like spider-silk...?

The sages say

sleep is one-sixtieth

of death. Perhaps one

who rarely wakes

can glimpse the other side.

"My God, the soul You have placed within me is pure..." comes from the prayer Elohai Neshama. My favorite translation contains the line "You created it, you formed it, you placed it within me, and you will take it from me in a time beyond time."

The imagery of a soul sheltered beneath the wings of Shekhinah is drawn from the prayer El Maleh Rachamim.

The teaching that sleep is 1/60th of death comes from the Talmud.

December 2, 2014

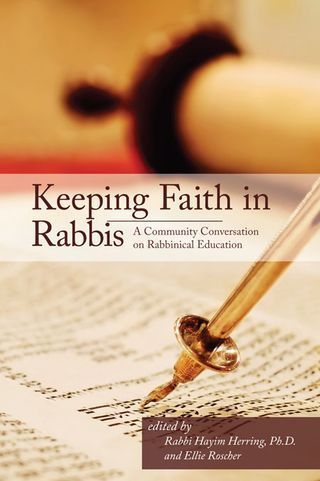

An essay in Keeping Faith in Rabbis

I'm delighted to be able to announce that I have an essay in a new volume called Keeping Faith in Rabbis: A Community Conversation on Rabbinical Education, edited by Ellie Roscher and Rabbi Hayyim Herring, new this month from Avenida Books.

I'm delighted to be able to announce that I have an essay in a new volume called Keeping Faith in Rabbis: A Community Conversation on Rabbinical Education, edited by Ellie Roscher and Rabbi Hayyim Herring, new this month from Avenida Books.

Here's how the editors describe the volume:

Keeping Faith in Rabbis: A Community Conversation on Rabbinical Education is an original book of essays by rabbis, academics and lay leaders who explore the question, “What goes into the making of a 21st Century rabbinical leader?” Keeping Faith in Rabbis does not prescribe formulas for rabbinical education. Rather, it is an intentionally curated conversation across ideological boundaries that both celebrates the work of rabbis and suggests new paradigms of rabbinical education and leadership.

The list of contributors includes some real luminaries. My essay "In the Right Direction: Hashpaah and Spiritual Life" appears alongside "Speaking Torah: from Stammering to Song" by Rabbi Sharon Cohen Anisfeld; "The Loneliness of the Rabbi" by Rabbi Harold M. Schulweiss; "A Letter to a New Reform Rabbi" by Rabbi Rami Shapiro; and "Growing Rabbis" by Rabbi David A. Teutsch. (I'm also especially looking forward to reading "The Roar of the Cat Rabbi: The Vital Role of Introverts in the Congregational Rabbinate" by Rabbi Edward C. Bernstein� -- because I straddle the line between introvert and extrovert, and I just love that essay's title.)

It is a particular delight for me that my words will appear alongside the words of some of my ALEPH colleagues, including Rabbi Julie Hilton Danaan and Rabbi Geela Rayzel Raphael, and some of my Rabbis Without Borders colleagues, including Rabbi Richard Hirsh.

Here's some of what others have said about it so far:

“Keeping Faith in Rabbis is like having coffee with 33 rabbis and lay leaders who speak to you as a trusted confidant. Before you get to the last drop, you’ve been challenged, and inspired to re-imagine the future of rabbinic leadership and education for our changing world.” –Cyd Weissman, Director of Innovation, Congregational Learning, The Jewish Education Project, Adjunct Lecturer Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion

“Keeping Faith in Rabbis delivers even more than it promises. Through the conversation about raising up the rabbis of tomorrow, the essays in this volume put forth bold visions of what Jewish life in America could yet be. These are voices of leadership, unfettered.” –Professor Shaul Kelner, Professor of Sociology and Jewish Studies at Vanderbilt University

“Passionate, deeply personal, funny, erudite (though worn lightly), sometimes confessional, always thoughtful and reflective, the essays in Keeping Faith in Rabbis probe the changing demands on and possibilities for rabbinic leadership. Essential reading for everyone who cares about the future of Jewish life.” –Dr. Ronald Krebs, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Minnesota

Keeping the Faith in Rabbis is available from Avenida Books and on Amazon (Print edition $17.95 | Kindle edition $9.99). If you're interested in Jewish community or in questions of where the Jewish future may lie, I think this book will be a terrific resource -- and also hopefully a conversation-starter, both in our communities and in other liberal religious communities where the questions raised in this book will resonate. Pick up a copy today!

December 1, 2014

December / Kislev: be kind to yourself, and remember that you are enough

We're well into the lunar month of Kislev (which contains Chanukah), and on the Gregorian calendar today is the first day of the month of December. I remembered that I'd written something about this season which had to do with gentleness to oneself, so I went back to look -- and found that two years ago I shared excerpts from the very posts I was looking for. So I'm sharing the same excerpts again today.

Here is what I have to offer: be kind to yourself during these days. Pay attention to what your body is saying, to what your heart is saying, to the places where your mind gets tied in knots. What are the stories you tell yourself about this time of year? What are the old hurts to which you can't help returning, what are the old joys which you can't help anticipating?

Listen to your heart. Discern what awakens joy in you, as you anticipate the month of Kislev unfolding, and what awakens sadness or fear. Tell your emotions that you understand, you hear them, they don't have to clamor for your attention. Gentle them as you would gentle a spooked horse or an overwrought child.

-- A call for kindness during Kislev, 2011

[T]he matter of having enough, or not having enough, is surely an emotional one, as much as or more than it is a fiscal one. Scarcity is a kind of mitzrayim, a narrow place. And the fear of scarcity can be even worse, in the way the fear of a thing is usually worse than the thing itself. Fear of scarcity can be existential, can make the whole world seem constrained.

Fear of not having enough can blur into fear of not being enough. Fear that if we're not smart enough, or rich enough, or thin enough, we won't be valued. Won't be seen for who we really are. Won't be loved.

-- Enough, 2007

November 27, 2014

Gratitude, Thanksgiving, and the golden land

A still from "This Is America, Charlie Brown: The Mayflower Voyagers," 1973.

Today we remember a long-ago feast of gratitude. Perhaps that feast was held by Pilgrims along with their Wampanoag neighbors, who had helped the colonists survive the hardships of a brutal winter marked by sickness and loss (which had come after a difficult transatlantic crossing). Now there was a good harvest and sense of plenitude. (See Thanksgiving History | Plimoth Plantation.) That's more or less how the story unfolds on the Peanuts "This is America, Charlie Brown: The Mayflower Voyagers" special, and if Charles Schulz illustrated it, it must be true, right? (Hint: depends on who you ask.)

As a Jew I've always felt some identification with the Pilgrims who fled religious persecution and set off for a land where they could worship as they chose in peace. The same was true of both of my sets of grandparents during the 20th century. For many Eastern European Jews America was the Goldene Medina, the golden land of opportunity where all were equal and where religious freedom was guaranteed. In America anyone could get ahead if only they were willing to work hard. Something in me will always resonate with this vision of the United States as a place of equality and freedom.

Of course, the Pilgrims' arrival here was the beginning of an era of European colonization which left this land's Native inhabitants disenfranchised. That complicates the religious freedom narrative a bit. European religious freedom and expansion came at a high cost. Between European notions of land ownership and that era's triumphalist sensibilities -- not to mention "manifest destiny," the establishments of Indian reservations, and the import of smallpox and other European diseases -- the colonists set in motion a paradigm shift which would badly damage the fabric of Native life.

The tale of the First Thanksgiving may be biased mythologizing. And the fantasy of an America entirely free from prejudice, where anyone could "bootstrap" their way to prosperity, turns out to be not exactly the whole truth either. Both that classic Jewish immigrant story, and the Thanksgiving story as I learned it when I was a kid, are sanitized and rosy-hued. Intellectually I know that there is more to both of those realities than the neat narratives can explain. And yet there's something about these stories which is still compelling for me, even though I know they're not the whole truth.

What do these tales do for us? What purpose do they serve in our psychospiritual lives? I think the persistence of these stories shows us something about how we want to see ourselves and our nation. I think both stories encode a yearning for a home where harvests are plentiful, gratitude is free-flowing, and opportunities abound. They can teach us something real and true -- not about the way things were or are, necessarily, but about the way we wish things were.

In Jewish tradition we say that Shabbat offers us a taste of the world to come. When we tell these old stories about America as a haven of perfect equality and freedom, about the Pilgrims and the Indians sitting down in harmony, about a place of opportunity where a Jew can aspire even to the highest office in the land, I think we're seeking that same kind of taste of what it would be like for our nation to live up to our holiest ideals. Maybe today we celebrate the abundance, freedom, and thankfulness which characterize the America of our deepest hopes.

Happy Thanksgiving to all who celebrate.

November 26, 2014

Praying for what's possible

What does it mean to cultivate hope when the doctors say "there's nothing more we can do"? Hopes for a cure have to be set aside. There will be no miracle, no Hail Mary pass, no eleventh-hour wonder. Every specialist has been seen, every possible avenue of treatment or exploration exhausted. All of the tests have been run. What does it mean to pray for healing when the body cannot be healed?

What does it mean to cultivate hope when the doctors say "there's nothing more we can do"? Hopes for a cure have to be set aside. There will be no miracle, no Hail Mary pass, no eleventh-hour wonder. Every specialist has been seen, every possible avenue of treatment or exploration exhausted. All of the tests have been run. What does it mean to pray for healing when the body cannot be healed?

Every Shabbat morning after we read from Torah we offer a prayer called Mi Sheberach, "May the One Who Blessed..." It asks God, Who blessed our ancestors, to bless our sick loved ones with healing. Some years ago at my shul we began using an alternative text. We still ask God to bless those in need of healing of body, mind, and spirit. To be with them, comfort them, strengthen them and revive them.

But not to heal them. Because we recognize that not everyone who is ill can be healed. And as one of my congregants has taught me, asking God repeatedly for healing which we know is never coming can be painful. And it can lead to (entirely understandable) fury at God for not fulfilling the yearned-for wish. Her perspective is actually quite aligned with Jewish tradition, in a certain way. Tradition teaches us not to pray for the impossible, lest we damage our own faith in the Source of blessing.

During the dry season in the land of Israel, it never rains. So all over the world during that season, when we reach the line in our daily prayer which asks God for the nourishment we derive from water, Jews pray instead for dew. Because rain is simply not possible (in the place where our prayers originated), and we don't pray for things which are impossible, perhaps because doing so would be tantamount to "testing" God.

Jewish tradition teaches that when one hears a fire truck going by with sirens wailing, one shouldn't pray "please, God, let it not be my house burning" -- either it is, or it isn't, but the prayer won't change whatever is already real. I learned this when I first studied Mishna several years ago (see Brachot chapter 9) -- one who prays over something which has already happened is praying in vain. Sometimes a medical diagnosis can be like that. All we can change is how we respond to what is.

When a loved one cannot be healed, perhaps a time comes when we stop asking God for healing. We can ask for perspective, for strength, for loving care. We can ask God to be with our loved one and help them find blessings in each day. We can ask for comfort, for some sweetness to mitigate our loved one's suffering or grief. We can ask God to be with their caregivers, and to strengthen the work of their hands. We can ask for what is possible, and that has to be enough.

November 25, 2014

Injustice: the Ferguson grand jury's decision

I'm mostly offline this week, but I just saw the news that officer Darren Wilson, who shot unarmed teenager Michael Brown on August 9, will not face trial. (See Ferguson police officer won’t be charged in fatal shooting and Ferguson smolders day after grand jury decides not to indict officer.) Apparently this means that the grand jury decided that there was not "probable cause" that Wilson had committed a crime. The chair of the Congressional Black Caucus says that the Ferguson decision shows that black lives have no value.

This decision is part of a pattern (see Ferguson Cop Darren Wilson Is Just The Latest To Go Unprosecuted For A Fatal Shooting, which looks at shootings by police in the St. Louis area: "Since 2004, St. Louis County police officers have killed people in at least 14 cases. Few faced grand juries, and none was charged.") And I know that this is not only a problem in St. Louis. (See 'Epidemic of police violence in US’: Black person killed every 28 hours, and on CNN.com, Ferguson: the signal it sends about America.) While I'm sharing links, don't miss Chronicle of a riot foretold by Jelani Cobb in the New Yorker, which I found both painful and powerful.

My computer time right now is limited, and I don't have the spaciousness to craft an impassioned essay about how and why this is not the America of my hopes and dreams. (Instead I'll link you back to what I wrote a few days after Michael Brown's killing -- Grief at the deaths of unarmed black men.) But I am holding the family of Michael Brown (may his memory be a blessing) in my prayers. And I pray for change and for justice. In the words of the prophet Amos, "May justice roll like a river, righteousness like an ever-flowing stream."

Edited to add: I commend to you rabbinic student Sandra Lawson's A Prayer for Ferguson.

November 24, 2014

Dealing With Chronic Illness at The Wisdom Daily

I'm deeply delighted that the folks at The Wisdom Daily, a publication which I greatly admire, wanted to reprint a version of a blog post which first appeared here.

They reposted my piece about Toni Bernhard's book How to Be Sick as Dealing With Chronic Illness: Can You Do Well At Being Sick?

If you didn't read that post when it appeared here, or if you'd like a refresher, feel free to click through and read the (deftly edited) version they shared with their readers.

Thanks, Wisdom Daily!

November 21, 2014

Peace Parsha at APN - If this is so, then why am I?

Earlier this fall I was honored by the invitation to offer some words of Torah as part of the Peace Parsha series at Americans for Peace Now.

Earlier this fall I was honored by the invitation to offer some words of Torah as part of the Peace Parsha series at Americans for Peace Now.

You can read my commentary on parashat Toldot at APN: If this is so, then why am I? I'm also archiving it below.

"The children struggled in her womb, and she said, 'If this is so, then why am I?'" -- Genesis 25:22

We read in this week's Torah portion that even in the womb, Rebecca's children Jacob and Esau quarreled. And their perennial struggle brought her to an existential outcry: if this is so, then why am I? If this is the only possibility for my sons, she seems to be saying, then my motherhood -- even my whole existence -- feels called into question. If fighting is all there is, then what's the point?

I suspect that many of us who care deeply about Israel and Palestine have those moments of heartfelt crying-out. If this is so, then why am I? If struggle and violence are inevitable, "then why am I" giving my heart and soul to working toward peace?

The twins are different in every way. Esau is the elder son, bigger and stronger; Jacob is the younger son who prevails by his wits. Esau is an outdoorsman who likes to hunt; Jacob prefers their mother's tents. Generations of commentators saw Jacob as the proto-yeshiva-bucher and Torah scholar. (One midrash holds that whenever the pregnant Rebecca passed a yeshiva, Jacob would strain within her womb to lead her there.) As the story unfolds, Jacob outwits Esau out of his birthright (land inheritance), and then with Rebecca's help tricks Isaac into giving him the elder son's blessing, too.

As Jews we identify with Jacob, in part because our story tells us that he is the progenitor of our family line. But I think we also cheer for Jacob because he is an underdog who prevails through wits rather than through strength. Historically, that's how Jews have made our way in the world. As the younger brother, Jacob wasn't supposed to receive the blessing or the property inheritance due to the firstborn, but he outsmarted a system of inheritance which was weighted against him. We who have historical memories of being denied full citizenship, and living memories of being denied entry into universities and country clubs, can't help but cheer at Jacob's triumph.

Many of the family stories in Genesis are stories of inversion, where a younger brother prevails over the older. Just so, with God's help, we have prevailed for millennia in an often unkind world. When we struggled under Roman empire, we associated Esau with Rome. It's easy to interpret Israel's presence among many (sometimes hostile) Arab nations as another Jacob-and-Esau story, where once again we are the underdog who wrests control away from a region of Esau after Esau.

There's another way to map those two brothers onto today's Middle East. When the modern state of Israel was founded, the idea of a "new Jew" came into vogue. Brawny and tough, hardened by tilling the earth, the identity of the sabra veered away from the Jacob-style timidity which had, some said, made the horrors of the Shoah all too possible. The mythology of the early decades of the modern State of Israel aligned us for a change with Esau, the brawny hunter-gatherer, instead of with Jacob. Never again will we rely only on our wits: now we have an army.

But in the decades since 1967, that army has been tasked with . Maintaining ownership by military might has not led to peace between the two peoples any more than Jacob's claiming the firstborn's blessing by trickery led to peace between the two brothers. It would appear that whether we place ourselves in the Jacob role or the Esau role, peace is beyond our grasp. But are these our only choices? Is enmity between brothers the only possible paradigm for Jacob and Esau -- and, by extension, for Israelis and Palestinians?

Later in Torah, Jacob meets up again with his brother Esau after many years apart. (It's on the cusp of that fateful meeting that Jacob wrestles with the angel, gaining a new name in the process -- Israel, one who wrestles with God.) The brothers embrace and Esau offers words of joy. He marvels at his brother's good fortune -- by this time Jacob is quite wealthy, with wives and children and herds and flocks -- and invites his brother to travel with him. But Jacob is unable to trust his brother's overture. He makes excuses to take a different route, and they never meet again.

Every year when I read these verses, I wonder whether Jacob made the right call. Granted, his brother had threatened to kill him back in the day; he has good reason to fear. But what if Esau had grown and changed? What if his offer of peace and brotherhood were sincere? We'll never know; Jacob didn't have the inner resources to take the risk of finding out. But in our day we need to live out a different choice. We need to open our hearts to the leadership of courageous peacemakers on both sides. We need to learn how to act out of hope, not out of fear. We need to write a different ending to this story.

Torah teaches that the two brothers wrestled in the close confines of Rebecca's womb. Today Israelis and Palestinians are in an equally tight place: pressed together cheek by jowl and village by settlement, intertwined and struggling for dominance. Can we imagine a new birthing out of that narrow place, one which would lead to the emotional expansiveness required for coexistence?

Rebecca cried out to God in anguish at the tussling of her sons. She felt as though their struggle would annihilate her. Last summer when Israel and Gaza were at war, my heart broke again and again. Every time I read a news story, saw a Facebook update, glimpsed the war even from this distance, I felt as though witnessing that struggle in a place which I love would shatter my heart. And I wept at how the fighting was shattering the land and its inhabitants.

Our tradition teaches that it was the Israelites' cries, from the narrow place of slavery, which sparked the outflow of divine mercy leading to the Exodus. This is what the Zohar calls אתערותא דלתתא, "arousal from below." If our hearts break as we witness continued struggle in Israel and Palestine, and we cry out as Rebecca did, what new possibilities might we call forth from God's infinite reservoirs of compassion?

If eternal hatred and bloodshed are our only options, then Rebecca's cry still resonates: if this is so, then why am I? But I believe that a different reality is possible. If we will it, we can make it more than a dream.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers