Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 142

November 7, 2014

How to be sick well: Toni Bernhard's guide for the chronically ill

This book is written for people who are ill and aren't going to get better, and also for their caregivers, people who love them and suffer along with them in wishing that things were different. It speaks most specifically about physical illness. In the largest sense, though, I feel that this book is for all of us. Sooner or later, we are all going to not "get better."

That's acclaimed Jewish-Buddhist teacher Sylvia Boorstein in her introduction to How to Be Sick: A Buddhist-Inspired Guide for the Chronically Ill and Their Caregivers by Toni Bernhard.

The book was recommended to me by one of my congregants who cares for a chronically ill loved one. She described Bernhard's book as "How to be sick well" -- how to achieve emotional and spiritual wellness even when one's body remains sick.

Bernhard became ill in 2001 and has suffered from chronic illness ever since. The first two chapters tell the story of her illness. Beginning in chapter three she shares how her Buddhist learning offered her a way of approaching her illness as a spiritual practice. She wanted to know "how to live a life of equanimity and joy despite my physical and energetic limitations." This book offers her answers to that question.

Early in that third chapter she writes about the power of "just being" with what is:

Just "being" life as it is for me has meant ending my professional career years before I expected to, being house-bound and even bed-bound much of the time, feeling continually sick in the body, and not being able to socialize very often. [Drawing on Buddhist teaching,] I was able to use these facts that make up my life as a starting point. I began to bow down to these facts, to accept them, to be them. And then from there, I looked around to see what life had to offer. And I found a lot.

I struggle a little bit with her language of "bowing down to" these facts. And yet I recognize that there is wisdom in accepting what is, instead of getting caught up in wishing that things were different. I know that in my own life I get into trouble when I get attached to my expectations of how something will be, and I feel more open to blessings when I can simply be with what is.

This is a book rooted in Buddhist terminology and thinking. But Bernhard does a good job of explaining how these concepts relate to the life we all share. For instance, the "first noble truth" of the Buddha is that dukkha, usually rendered as "suffering," is an inevitable part of human life. Bernhard notes that it is balanced by the equally true reality that joy and happiness are also part of human life. Most of us prefer to focus on the joy and avoid or ignore the suffering, but both of these are part of being alive.

The Buddha taught that he could offer an end to suffering, but he didn't mean physical suffering, which is an inescapable part of the human condition. Human beings have bodies; bodies feel pain and discomfort; there is no way to entirely avoid that in this life. But the Buddha's teachings offered Bernhard a valuable path toward ending mental suffering. No matter what we are experiencing in our bodies, we can always cultivate a mental state which will lift us out of that suffering. She writes:

I work on treating thoughts and moods as wind, blowing into the mind and blowing out. We can't control what thoughts arise in the mind. (Telling yourself not to think about whether you'll feel well enough to join the family for dinner is almost a guarantee that it's exactly what you will think about!) And moods are as uncontrollable as thoughts. Blue moods arise uninvited, as does fear or anxiety. By working with this wind metaphor, I can hold painful thoughts and blue moods more lightly, knowing they'll blow on through soon -- after all, that's what they do.

I offer words similar to these (about thoughts arising and passing) every week at our meditation minyan. And I like her teaching that moods are ultimately changeable, too -- though I will note that when I have wrestled with substantive anxiety or depression, moods have been more pervasive than what she describes. (Dear reader: if you are experiencing a "blue mood" which does not pass, please seek the counsel of a therapist.)

Bernhard writes about Buddhism's four "sublime states" of lovingkindness; compassion; joy in the joy of others; and equanimity, a mind that is at peace in all circumstances. (I've posted about equanimity a few times, drawing on teachings from Hasidic and Mussar traditions: Shviti and Cultivating equanimity.) "Cultivating joy in the joy of others has been central in coming to terms with the life I can no longer lead. Without this, I'd be steeped in envy," she writes.

Lovingkindness, compassion, and equanimity are all familiar ideas to me from my own tradition. But the idea of specifically cultivating joy in the joy of others was new to me. Bernhard explains that she has made a conscious effort to feel genuinely glad for people who got to do things she couldn't do, and to consciously affirm joy in their good fortune. At first, she admits, that felt "fake" to her-- but over time the fake practice became real, and now it is second nature.

The "fake it 'til you make it" approach is something I've experienced in Jewish practice, as well. As Rabbi Jeff Roth taught me many years ago, on mornings when I can't access genuine gratitude as I pray the words of the modah ani, I can recite the words in the hope that gratitude will arise for me again. If I waited until I fully felt the meaning before I said the words, I might never pray at all. Sometimes saying the words with regularity is part of what trains my heart and soul to feel the gratitude and the awe which the words express.

I noticed, as I was reading, that some parts of the book resonated with me, and other parts of the book made me want to argue. For instance, I felt some discomfort when I encountered her teaching that suffering can arise from one's desire for certainty and predictability. I felt an immediate and visceral push-back: Hey, what's wrong with wanting predictability? I try hard to create predictability for our child in my parenting life! (Which, of course, says more about me and my attachments than about it does about her teaching.)

And yet I recognize that for someone who is chronically ill, certainty and predictability are in short supply. On a given day, Bernhard may or may not feel up to getting out of bed, or seeing people, or leaving the house. Those are no longer the kinds of things on which she can count. But she writes poignantly about how, when she can let go of the desire for certainty, she can access a different kind of freedom. She writes:

Our tendency is, of course, to want our desires to be fulfilled. But if our happiness depends on that, we've set ourselves up for a life of suffering.

Reading that, I thought of something I've been reminding our son gently as his birthday approaches and as he notices ever more toys in the world which he would like to own: it's great that there are so many things in the world to want, and it's okay that he's not going to get them all. It's a tough lesson for a five-year-old to learn, though this book helped me recognize how we are all prone to the challenges of thwarted desires. Of course we all want things. And, we all have to learn how to be okay with the fact that we don't always get what we want... whether what we want is a new toy, or healing from an illness which isn't going away.

It's better, she writes, to learn to choose a different train of thought:

As I lay in bed, the flu-like symptoms were indeed physically unpleasant. But, instead of mindlessly allowing aversion to arise as I had done thousands of times in the past, I realized I had a choice of where to put my mind. So I consciously moved my mind to lovingkindness, silently repeating "Dear sweet, innocent body, working so hard to support me." Directing this well-wishing at my own body was my doorway out of dukkha [suffering]. I got off the wheel of suffering. I was free from aversion to my illness and from all that can follow from that aversion -- for example, becoming and being reborn as a bitter and resentful person.

(When she speaks about being reborn, she isn't referring to reincarnation per se, but to the idea that we are reborn in every moment. If I cultivate anger, then I am being reborn as an angry person. If I cultivate equanimity, then I help myself to be reborn in this moment as someone who is calm and at peace. I think this relates to the idea of carving new grooves on heart and mind.)

Bernhard offers several valuable mental practices. One of my favorites is "dropping it." First, she teaches, focus on something sad in the past ("there are treatments I regret having tried, and recalling them gives rise to stressful thoughts such as 'Am I sicker today because of that potentially toxic antiviral I took for a year with no positive results'") -- and then just drop it. "Maybe you can drop it for only a microsecond, but just drop it and direct your attention to some current sensory input," she urges, and feel the relief which ensues. And make this a regular practice. "With practice, you'll find that at the command 'drop it,' the memory is gone and so is the suffering that accompanied it."

I also really like her teaching about how to respond to one's own frustrations with compassion. For instance, someone who is feeling sad and frustrated about missing a family gathering due to illness might say to themself, compassionately, "It's so hard not to be able to join the family for dinner." Like the teaching about thwarted desire, this one too makes me think of our son, because I often try to comfort him in this way: by letting him know that I hear him, and I understand what he's feeling, and I empathize with where he's at. But I hadn't thought in terms of bringing that same kind of compassionate listening to the cries of one's own heart.

Toward the end of the book, she writes:

Living well with chronic illness is a work in progress for me. Some days, I still cry out:

"I can't stand this oppressive, sickly fatigue one more day!"

"I don't care if stressful thoughts exacerbate my physical symptoms!"

"I don't want to hear that laughter coming from the living room!"

"I don't care if this is the Way Things Are: I don't want to be sick!"

When this happens I "put my head in the lap of the Buddha," as the Dalai Lama suggests, and again take refuge in one of the practices I've shared in this book.

This is a brave and necessary book, and I admire Bernhard tremendously for writing it. I hope that having read it will help me be a more compassionate and caring pastoral presence.

November 6, 2014

Thanks, Berkshires Week!

Many thanks to Kate Abbott of Berkshires Week, the weekly magazine which is part of The Berkshire Eagle, for the lovely article about Jewish Book Month happenings in Berkshire County. The article begins with a quote from one of the poems in my first book 70 faces: Torah poems (Phoenicia, 2011.) It continues with some history of Jewish Book Month, and a recounting of a conversation between Kate and me:

I asked Rachel what books she would recommend, if she and I were putting together a list of wonderful things to suggest to people this month -- people who would love words and stories as much as we do and see new worlds to explore.

Off the top of her head, she suggested "The Rabbi's Cat," a gentle graphic novel by Joann Sfar; "The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay," a novel set in the early days of comic books by Michael Chabon; "The Golem and the Jinni" by Helene Wecker...

Read the whole thing here: Berkshires Join Jewish Book Month. (For those who are interested: I posted about The Rabbi's Cat 2 here back in 2008, and about The Golem and the Jinni in January of this year.)

Thanks, Kate and Berkshires Week, for sharing word of some nice Jewish happenings in our county!

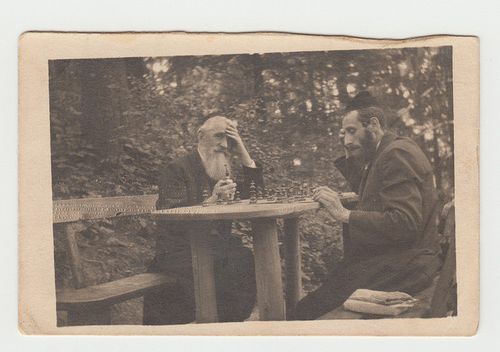

Chess

No one knows who these men are or why their photograph has been handed down in our family. If I had to guess, I would say that this photo is probably from Belarus, childhood home to my grandfather Isaac, a.k.a. Eppie (may his memory be a blessing). It is a tiny photo, only three and a half inches by two and a quarter inches. It was in a box of miscellaneous family photographs at my parents' house; I found it in a small envelope labeled "treasures old and new" in my mother's handwriting.

Who were these men? Religious Jews, it seems clear; they are bearded and wearing yarmulkes. Then again, they don't have peyos, the sidecurls which are seen on many Hasidic or Orthodox Jews, and their beards are trimmed neatly. (Though apparently peyos were banned in the Russian Empire in 1845.) It appears that they're wearing long black coats and black kippot, though that may or may not have been a signifier of anything in that place and time, whatever that place and time were.

I looked through The Family History of Alice Fried Epstein and Isaac Epstein, M.D., a volume which contains the transcript of oral history interviews conducted with my maternal grandparents. I remembered that the book contained a variety of black and white photographs, many of which were taken in Europe and date to the early years of the last century when my grandparents were young. But I didn't find either of these men in any of those pictures from early 20th-century Belarus or Prague.

Every time I look at this photograph I'm drawn to the man on the left, with the white beard, who has looked up from their chess game to regard the unknown photographer. I am charmed by his subtle smile. Presumably he knew whoever was taking this picture. Maybe he was winning the chess game. Maybe it was just a beautiful day in the park and he was happy to be alive. Could he have imagined this print traveling across the ocean and surviving more than a century to wind up in my hands?

I'm taking advantage of the #throwbackthursday / #tbt meme -- which usually involves posting old photos on Thursdays -- as an opportunity to write short snippets of remembrance, sparked by whatever old photo I find to post.

November 5, 2014

Preparing for shiva

Looking for a printable shiva minyan liturgy? There's one at the end of this post.

I almost always begin a shiva minyan by telling a story about what we're doing and why we're doing it. (Shiva means seven and minyan means the group of at-least-ten who gather together to pray; a shiva minyan is a prayer gathering during the week called shiva, the first week after a loved one's burial.)

The custom of the shiva minyan came about, I explain, at a place and time where it was assumed that all Jewish men considered themselves obligated to pray three times a day. (This often draws forth a chuckle from the room, because we know that this is not how most of us in the room approach our prayer lives.) Imagine that you have the custom of going to shul every day: both because you feel metzuveh (commanded / obligated) to daven (pray) in community, and because you want to help the community make a minyan, the quorum of ten which is required for our call-and-response prayers, among them the Mourner's Kaddish.

Suddenly your life is ruptured by loss. A loved one dies. Now your days feel strange and measureless as you navigate this new landscape of aveilut, mourning and bereavement. The sages of our tradition recognized that in the wake of a loved one's death, the mere prospect of getting dressed nicely and leaving the house may feel completely overwhelming. So during the first week of mourning, the minyan comes to you. The community comes to your home; they bring prayerbooks, they bring food, they sit with you and listen to you and daven with you so that you can recite the Mourner's Kaddish in the embrace of loving community.

A shiva minyan, in other words, is intended to be something to soothe and comfort the mourner -- not yet-another-thing for the mourner to worry about doing, or doing "right." It's not supposed to be an onerous obligation; it's supposed to remove the onerousness from the obligation which one has already taken on, the obligation of daily communal prayer. But for those who don't have a practice of daily communal liturgical prayer, and/or who may not be especially comfortable with the Hebrew of traditional Jewish liturgy, the prospect of a shiva minyan may seem daunting. It may feel like an unwanted obligation, or be a source of discomfort, which is exactly the opposite of its purpose.

What might make a shiva minyan more approachable, even comforting, rather than intimidating? What matters most, I think, is the gentle presence of someone who can create a safe container for worship and for grieving. It is the hearts of the people present, and perhaps especially the heart of the person leading the prayer and seeking thereby to open a channel between the community and God, which create a shiva minyan that can offer healing. But it doesn't hurt to also have a set of prayer materials which will speak to people where they are.

Maybe that means transliterations. Maybe it means skillful translations. Maybe it means augmenting the traditional texts with a well-chosen poem or song -- bearing in mind that the purpose of the shiva minyan is to allow the mourner to slot into the familiar groove of reciting Mourner's Kaddish, and that too much ornamentation would risk detracting from that holy purpose.

All of this has been on my mind as I've been updating my shul's shiva minyan booklets, with grateful acknowledgement to my predecessor Reb Jeff from whom I inherited a lovely, simple, and classical homegrown booklet for evening prayer in a house of mourning. After some years of being carted around from house to house, many copies had disappeared, and the ones which remained were getting a bit worn. It was time to reprint, which meant there was also an opportunity to revise.

The heart of any shiva minyan booklet is the standard daily service. Since our community does not have a weekday morning minyan, our shiva minyanim are always in the evening -- which means the core liturgy is the evening liturgy, which typically takes about 30 minutes to pray. I began with the same material which was in our old booklets: the lighting of a memorial candle, the call to prayer, the Shema and her blessings, the silent Amidah / standing prayer which is at the heart of daily Jewish worship, the closing prayer known as the Aleinu, a special prayer of remembrance called Eil Maleh Rachamim ("God, full of compassion!"), and the Mourner's Kaddish.

And then I added a few things which I hope might speak to people for whom the traditional liturgy is opaque. Two poems from Beloved on the Earth: 150 Poems of Grief and Gratitude, which is one of my favorite resources. Reb Zalman's beautiful English rendering of the Shema. Some art which I found via Open Siddur. A set of one-line affirmations or meditations, on the themes of the weekday blessings in the Amidah, created by Reb Zalman (z"l) and by Rabbi Daniel Siegel, which I first encountered thanks to Rabbi Chava Bahle. A poem by Jane Kenyon, of blessed memory. And Reb Zalman (z"l)'s English rendering of the Mourner's Kaddish, which opens up a new level of understanding of the familiar cadences of the Aramaic.

It's still a simple folded xeroxed booklet. And I know that it doesn't matter nearly as much as whatever heart and presence I am able to muster. But I'm grateful to have had the opportunity to immerse myself for some hours in the combination of weekday liturgy and poems and prayers of mourning. I hope that the end result brings comfort.

If you have come to this post in search of a shiva booklet, you are welcome to use ours. The attached pdf is meant to be printed duplex (two-sided); the pages are oriented so that when you print it that way and then fold the sheaf in half, everything will be right-side-up and in the right order.

If you are alone and in mourning, you may prefer to substitute the special version of the Kaddish designed for solo prayer, which you can find on Reb Daniel's blog.

May the Source of Peace bring peace to all who mourn, and comfort to all who are bereaved.

Revised-Shiva-Booklet [pdf] 368kb

Thanks, Moment!

It's lovely to be the Jewish Renewal voice quoted in this Moment magazine article about cultured meat and its putative kashrut. (Science fiction future, here we come?) Here's how it begins:

In Genesis, God granted humans dominion over animals. In modern times, that dominion has spawned one of the planet’s biggest threats: a livestock industry that spews greenhouse gases, guzzles resources and renders the lives of billions of animals brutish and short. Last August, vexed by the problem, a Dutch physiologist named Mark Post came up with a solution: a burger no cow had to die for. He called it the “test-tube burger.”...

Read the whole thing here: Test Tube Burgers: Holy Cow? (I don't chime in until the very end, but I'm honored to have the last word!)

November 4, 2014

This just in - no poetry reading on Thursday

I posted yesterday about a poetry reading I was scheduled to give this Thursday. That reading has been canceled because I will be doing a funeral at that time. Please join me in holding the bereaved family in our hearts and in our prayers.

November 3, 2014

We have to build a better world than this

This post talks about violence against women. If that is likely to be triggering for you, please guard your own boundaries and read with care.

What can I say in response to the many awful things wrong in the world? The endless news ticker of atrocities both large and small, the many entirely legitimate reasons to be furious and to feel despair? This week my Twitter stream is peppered with posts about Gamergate and Jian Ghomeshi -- two currently-unfolding stories having to do with rape, assault, intimidation, and violence against women.

Violence against women -- from rape, to "doxxing," to other forms of silencing and intimidation -- is everywhere. We read about it in Torah (see On the silencing of Dinah) and we read about it in the news. I am trying to hold all women who have been victimized in my prayers. May they know healing and wholeness, safety and comfort, integrity of body and integrity of spirit. May they not be afraid.

It's harder for me to pray for the men who have committed these transgressions. I find myself thinking of the generation of Israelites who left Egypt and didn't make it to the promised land, their psyches too scarred by slavery to allow them the expansiveness of a new way of being. I wonder whether it's possible to redeem men who are so steeped in toxic entitlement that they would commit such acts.

And then I remind myself that ultimately forgiveness and consequences are in God's hands, not mine. (Thank God for that.) But I do have control over how I cultivate my own compassion and kindness. And I can do everything in my power to show the boys whom I teach, and the boy who I am raising, how to treat women with the respect due to one who is made b'tzelem Elokim, in the divine Image.

Pirkei Avot teaches that it's not incumbent on us to finish the work, but neither are we free to refrain from beginning it. Creating a world where women can live without fear -- that's part of the work. We have to build a better world than this. Full disclosure: I'm not sure how. People hurt other people out of alienation, and I don't know how to heal that. I don't know how to fix a problem this systemic.

But I know that we have to try. That the world needs more kindness. That we all long to feel at-home and cherished for who we are. That Jewish tradition teaches us to cultivate hope in place of despair. It's not incumbent on us to finish the work, but neither are we free to refrain from beginning it. Write, teach, help, listen, pray, mentor, be kind: what can you to do begin creating the world we need?

Resources:

For survivors: Ritualwell has a good collection of resources on healing from trauma and abuse, and some of those resources are tagged specifically for survivors of rape.

Worth reading: Lisa Batya Feld's GamerGate: Why We All Lose at the JWA (Jewish Women's Archive / Jewesses With Attitude) blog

Poetry reading in Pittsfield

November is Jewish Book Month. Jewish Book Month is an annual event of the Jewish Book Council dedicated to the celebration of (what else?) Jewish books. The Jewish Federation of the Berkshires is sponsoring a variety of Jewish Book Month events around the county during November.

I'm delighted to be able to let y'all know that Jewish Federation of the Berkshires has invited me to be part of the county's Jewish Book Month programming. I'll be sharing some of my poems at 1pm on Thursday, November 6 at Knesset Israel on Colt Road in Pittsfield.

A kosher hot lunch will be provided at Knesset Israel at 12pm; the poetry reading will follow at 1pm, and all are welcome to come for one or both. If one comes only to the reading, the cost is $3 (I believe that the kosher hot lunch requires a reservation -- you can confirm that by calling Jewish Federation or Knesset Israel.)

Here's a description of the event:

Poetry of Sacred Time

Join poet and rabbi Rachel Barenblat (author of 70 faces: Torah poems and Waiting to Unfold, both published by Phoenicia Publishing, and of the forthcoming Open My Lips, coming from Ben Yehuda Press) for a poetry reading which dips into the wellsprings of Jewish sacred time. Rabbi Barenblat will share Torah poems, motherhood poems, and poems which engage with Jewish liturgy and with the unfolding of our festival year. Q-and-A and booksigning to follow.

If you're in the area, I hope you'll join us. I'll have copies of my books available for sale and am happy to inscribe them. They make great Chanukah gifts!

November 2, 2014

The One Who Sees Me: a short d'var Torah for parashat Lech Lecha

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul. (Cross-posted to my congregational From the Rabbi blog.)

In this week's Torah portion God calls to Avram with the words "lech-lecha" -- "go forth!" or "go you forth!" or perhaps even "go forth into yourself." God calls Avram to leave the house of his father and venture forward to the place which God will show him. God promises him that his descendants will be as numerous as the stars. But his wife Sarai is unable to conceive. She gives him her slave-woman Hagar as a concubine so that Avram can father an heir.

In this week's Torah portion God calls to Avram with the words "lech-lecha" -- "go forth!" or "go you forth!" or perhaps even "go forth into yourself." God calls Avram to leave the house of his father and venture forward to the place which God will show him. God promises him that his descendants will be as numerous as the stars. But his wife Sarai is unable to conceive. She gives him her slave-woman Hagar as a concubine so that Avram can father an heir.

Once Hagar is pregnant, she treats her mistress with disdain. Sarai, in turn, is so abusive that Hagar runs away. That's when Hagar has the encounter with the angel.

The angel tells her that her descendants will be too numerous to count -- the same promise which was given by God to Avram. He tells her that she will bear a son and will call him Ishma-el, because "shama El," God has heard you. (If you remember the story of Chanah who yearned for a son, which we read on the first day of Rosh Hashanah, her son's name Shmuel comes from those same words, and means the same thing.)

In return for learning her future son's name, Hagar gives a new name to God. She names God as El Ro'i, "The One Who Sees Me." And on that theme of seeing, she asserts that she has seen God: "even here I have seen the back of the One Who looks upon me!"

Many generations later, Moshe will plead to be shown God's glory. God will shelter him in the crevice of a rock and as God's goodness passes by, Moshe will see God's back, or perhaps God's afterimage, a reverberation of divine Presence. Our tradition considers Moshe the greatest prophet who ever was or will be; Moshe had a direct relationship with God! And yet now we see that Hagar, "The Stranger," the slavewoman, has just seen God in the same way.

Later in this week's Torah portion, God renames Avram as Avraham and Sarai as Sarah. In Torah, a changed name means a changed inner being. , which can represent divine presence, or divine breath, or the deep hidden wisdom of the Five Books of the Torah. So what does God's new name tell us about the nature of God?

Hagar names God in a very personal way: not only "The One Who Sees," but "The One Who Sees Me." God is the One Who sees each of us, in our triumph and in our distress. God is the One Who sees through our masks and pretenses to the core of who we most deeply are. God sees our hopes, our fears, and our dreams. When we try to flee from the things in our lives which are most difficult or painful, God sees us where we are.

Being truly seen means being vulnerable. Maybe that's frightening. I think it's also a gift. God is the One Who Sees Me. And you. And you. And you.

I experience Torah not only as a story about those people then, but also about each of us now. Each of us is Avram, called by God to go forth, to go deeply into ourselves. Each of us is Sarai, trying to do the right thing, and struggling with jealousy sometimes. And each of us is Hagar, seen by God and seeing God in turn.

As we walk the journey of self-discovery, we are never alone. Even in times of despair, may each of us feel in our hearts that God is El Ro'i, the One Who Sees Me and responds with love.

October 31, 2014

"To boldly go": on Lech Lecha and Star Trek

Space: the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Its continuing mission: to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no one has gone before. [Source]

If you're a Star Trek fan, just reading those words has probably caused the theme music to swirl wildly through your head.

(I've just revealed myself as a fan of Next Generation, since those are the opening lines of that second iteration of the show. In the original series, the opening lines referenced the Enterprise's "five-year mission," and closed "where no man has gone before." Among my college friends, it was common to whoop and cheer out loud when we heard Sir Patrick Stewart intone "no one has gone before.")

This week's Torah portion begins on a similar note. We're reading Lech-Lecha this week, which begins:

וַיֹּאמֶר ה' אֶל-אַבְרָם, לֶךְ-לְךָ מֵאַרְצְךָ וּמִמּוֹלַדְתְּךָ וּמִבֵּית אָבִיךָ, אֶל-הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר אַרְאֶךָּ...

The Eternal said to Abram: "go forth from your land, your birthplace, your father's house, to the land that I will show you....

These are the voyages of the patriarch Abraham. (He'll inherit the extra syllable in this week's portion.) His continuing mission: to explore the ancient Near East, to seek out new tribes and new civilizations, and -- spiritually, at least -- to boldly go where no one had gone before.

Abraham is regarded as the first monotheist. Midrash holds that his father Terach was a maker of idols, and that young Abram knew them as false gods and smashed them in his father's workshop. (The same story appears in the Qur'an, as I've mentioned before.) In this week's Torah portion, God tells Abram to boldly go toward a destination which will be revealed as he gets there.

Abraham's travels show the importance of the journey. He displays emunah, faith and trust, by allowing himself to wander where God will take him. Jewish tradition holds that he was a paragon of hospitality whose tent was open to all comers. In that, he's not so different from the crew of the USS Enterprise -- though their wanderings aren't explicitly theological. Theirs is a secular humanist vision.

Abraham's descendants, too, will wander in what could be seen as a continuation of his voyages. (Judaism: The Next Generation.) Jewish tradition imputes meaning even to the wandering in the wilderness which the Israelites will endure after the Exodus from Egypt, and Moses' life too seems to be more about the journey than the destination. I think we're still on Abraham's journey of discovery.

I like to read the opening words of this week's parsha, "lech-lecha," not only as "go forth" but "go forth into yourself." Each of us is Abraham. Each of us is on a voyage of discovery. We're all always going wherever God will lead us. And we're all always exploring new worlds -- even if we're doing so internally, on emotional and spiritual planes, rather than in the vastness of the Gamma quadrant.

With gratitude to Joy Fleisig (@datadivajf) and Lee Weissman (@jihadijew) for the Twitter conversation which sparked this idea!

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers