Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 137

January 22, 2015

Gratitude for my body

I sat down this morning wanting to do some writing, and when I let my mind clear, what emerged was this subject. Even as I was writing this post, I had the sneaking feeling I had written something similar before -- but I intentionally didn't seek out that older post until I had finished drafting this one. It turns out that I've written almost this exact post before -- two years ago in deep midwinter, just like now. Apparently this is stuff I think about a lot, maybe especially at this time of year.

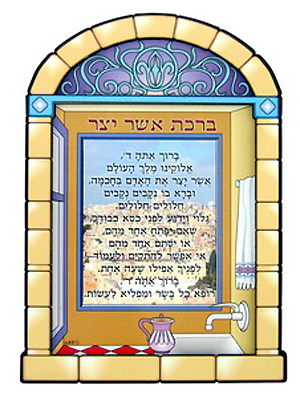

I don't manage to say 100 blessings every day. Actually, I'm not certain of that; it's not as though I'm keeping score, making a note on my phone every time I remember to bless. There may in fact be days when I organically offer a hundred moments of gratitude to God. But I suspect that most days my count is lower than that. Still, one blessing I offer every day is the asher yatzar. Here's how it goes:

I don't manage to say 100 blessings every day. Actually, I'm not certain of that; it's not as though I'm keeping score, making a note on my phone every time I remember to bless. There may in fact be days when I organically offer a hundred moments of gratitude to God. But I suspect that most days my count is lower than that. Still, one blessing I offer every day is the asher yatzar. Here's how it goes:

Blessed are You, Adonai our God, source of all being; You formed the human body with wisdom, and placed within it many openings and closings. It is known before Your throne of glory that if one of these were to be opened where it should be closed, or closed where it should be opened, we would not be able to stand before You and offer praise. Blessed are You, Adonai, healer of all flesh and worker of miracles!

I first became conscious of this blessing as a practice because it was printed on laminated posters which hung just outside the bathrooms at the old Elat Chayyim in Accord, New York. The words were there as a reminder to us that in Jewish tradition, even the act of elimination can be sanctified with words of blessing. I'm pretty certain that when I first encountered it I was charmed by the fact that we have blessings for pretty much everything. But I know it didn't really hit home for me then.

The blessing made a whole new kind of sense to me once I landed in the hospital with that second stroke. It is known that if one of these were to be closed where it should be opened... if a blood clot, for instance, should travel to the brain and block the flow of blood where it is needed... I would be unable to stand before You, indeed. My own brushes with illness have brought this truth home for me in a new way. And although I am (thank God) healthy and hearty now, the blessing's truth remains.

The truth is, having a body which more or less works most of the time is a flat-out miracle. Most of us don't tend to think of it that way, because it's incredibly difficult to live in the world while also feeling genuine wonder at every single miracle which occurs. My heart is beating: that's amazing! Hey, it's still beating: amazing! My kidneys are filtering my blood without my conscious control: amazing! No one can live with that awareness all the time. But our lack of awareness doesn't negate the miracle.

When I became pregnant I started experiencing the blessing in yet another way. Because I was a stroke survivor, and pregnancy increases the risk of stroke, I needed to inject myself with blood thinner every day. I am one of those people who shies away from needles even at the safe distance of seeing them on tv, so I was anxious about having to begin every day with an injection. So I developed the practice of reciting the asher yatzar while administering the blood thinner each morning.

Pregnancy also offered me new opportunities to marvel at the things my body does without my conscious intervention. Not only does my heart continue to beat, not only do my organs continue to do all of the things they're meant to do, but somehow my body knew how to grow a human being. I certainly wasn't driving that bus. My body knew what it was doing without me needing to be in charge. My body knew how to grow and change in ways I couldn't possibly have imagined.

And then our son was born, and the injections ended, and my relationship with my body went through a rollercoaster of changes: wonder that I had grown a human being from component cells, amazement that my body could produce the nourishment he needed, and then exhaustion and postpartum depression which deadened me to the wonder of my body (and of anything else.) I think there was a period of time when I wasn't saying many blessings for anything at all, my body included.

These days I silently recite the blessing every morning while I'm doing the incredibly mundane task of moisturizing my skin. This is a kind of routine wintertime maintenance for me. Between the cold dry air outside and the heated air indoors my skin gets dry and itchy at this time of year. It's a minor affliction, and it can be averted with a little bit of lotion. I try to use the moisturizing time to cultivate gratitude for my body. And as soon as I reach for the lotion, the blessing pops into my head.

Along with the words comes a melody. I sing them silently to myself using the trope, the melody-system, for Song of Songs. In rabbinic school I learned to use that melody for the sheva brachot, the seven blessings at the heart of every Jewish wedding. (I think that's a beautiful tradition. It makes sense that we would sing wedding blessings using the melody-system designed for Tanakh's great love-text.) So if it's a melody I associate with wedding blessings, why am I humming it to myself?

Because one of those seven blessings begins with the same words as the asher yatzar blessing -- "Blessed are You Adonai our God, Source of all being, Who creates the human being..." The wedding blessing goes on from there in a different direction, but because I have sung those words so frequently to this melody, the melody and the words have become intertwined. So when I am reciting the asher yatzar blessing to myself in the morning, that's the melody which arises.

I love praying the asher yatzar blessing to this melody because it makes the prayer feel like a love song both to my body, flawed and imperfect as it is, and to the One Who creates me anew in every moment. Singing a love song to my body isn't always easy. I know I'm not alone in looking in the mirror and seeing everything I like least about this physical form. But this blessing reminds me to look beyond those things to the miracle which underlies them. My heart is beating: that's amazing!

I can't live in constant awareness of these miracles. But if saying the blessing every day offers me an opportunity to glimpse the wonder again for a moment, that feels like enough.

Related:

Sanctifying the body, 2005

Morning blessings for body and soul, 2007

Every body is a reflection of God, 2013

A daily love song to my body, 2013

January 20, 2015

Legends of the Talmud: fantastical stories, in fantastic art

Donating to Kickstarter campaigns is like giving a gift to one's future self. I didn't come up with that idea myself -- it's Ethan's -- but I thought of it a few days ago when I received a copy of a book I had helped to fund, but had forgotten would be arriving eventually in my mailbox: Legends of the Talmud: A Collection of Ancient Magical Jewish Tales, by Leah Vincent and Samuel Katz, illustrated by Aya Rosen. (I reviewed Leah Vincent's memoir Cut me loose a bit less than a year ago.)

Here's how the project was described on its Kickstarter page:

Legends of the Talmud will introduce readers aged 6+ to one of the oldest and most influential texts of Judaism: the Talmud. Although often viewed as a collection of religious laws, the Talmud is also a cultural legacy filled with foundational Jewish ideas and magical tales.

The five stories curated in Legends of the Talmud are presented without doctrinal overlay. They are recounted exactly as they are in the original text: cultural treasures that depict earthy and frank experiences of love, suffering, hope and persistence that all humans grapple with as we move through life.

Written by Leah Vincent and Samuel Katz and illustrated by Aya Rosen, this revolutionary book will introduce children of all backgrounds to the Talmud and allow Jewish legends to proudly take their place in the global library of ancient magical stories.

The book does what the Kickstarter promised and then some. It is stunning.

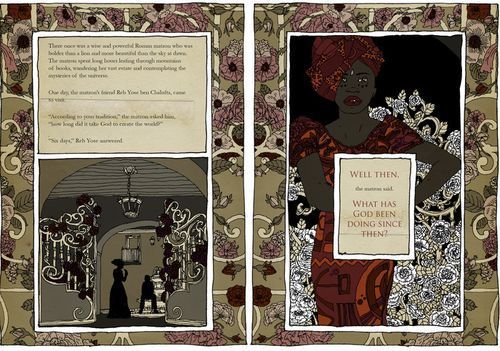

A two-page spread from one of the book's stories, "The Matron and Reb Yose."

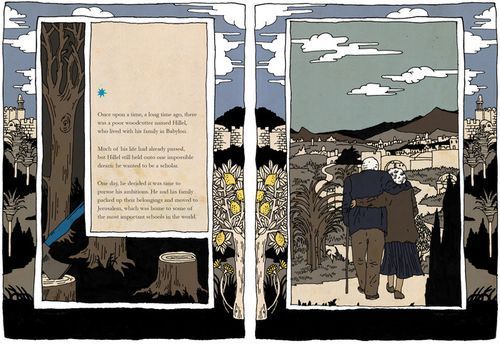

This is a richly-illustrated collection of short stories. (I can't exactly call it a graphic novel, because it isn't a novel, but it's very much in that vein -- beautiful illustrations which are themselves the story, not just accompaniments to the story.) It contains five vignettes from the Talmud: For the Love of Chanina, Hillel the Sage, the Test of the Bitter Waters, It is Not in Heaven, and the Matron and Reb Yose.

In these tales we read about how the sage Chanina loved learning more than he loved the law (and what the consequences of that love turned out to be). How the sage Hillel allowed himself to freeze overnight on the skylight of the house of study (and his famous on-one-foot encapsulation of Torah). How the sotah ritual, the "test of the bitter waters," allowed a woman who knew she had not sinned to prove her innocence. How the rabbis reminded God that interpretation of Torah is not in heaven, but here on earth, which means that it is in our hands. And how God spends God's spare time making love matches here on earth, which is a more difficult task than we tend to think.

A two-page spread from the tale of Hillel the Sage.

These are all stories that I know, and if you have spent any time studying Talmud, you know them too. But even if they are familiar to you, this volume's sparse retelling (and especially Aya Rosen's gorgeous artwork) will bring them to life for you in a new way. And if you know someone who doesn't know these tales from the Talmud, oh, is that person in for a treat!

I want to give this book to everyone I know who loves graphic novels, because it's a beautiful introduction to some foundational Jewish stories. (I give the authors particular props for including the whole "It is not in heaven" story -- not ending with God's joyful shout of "my children have defeated me," but going all the way to the story's conclusion, which is considerably more emotionally complicated.) And I want to give it to everyone I know who loves Talmud, because it's such a lovely addition to the corpus of Talmudic lore.

Leah Vincent's website says the books will be available at our favorite booksellers in spring of 2015, and a Twitter conversation with her confirms that. Follow the book's Facebook page to get an update when the book is available to the general public. Ass soon as that happens, I'm buying a pile of these -- to give to my b'nei mitzvah students and to share with comics-loving friends, and especially one to give to our son.

January 15, 2015

A Year of Deep Ecumenism - including a Jew in the Lotus 25th Anniversary weekend

The very first class I took, when I was in the process of preparing to apply to the ALEPH rabbinic ordination program, was Deep Ecumenism. (It's a required class for all students in the ALEPH ordination programs.) Deep Ecumenism was one of the pillars of Reb Zalman's thinking. It's a way of relating to other faith-traditions which goes beyond the shallow waters of "interfaith dialogue," and which eschews the old-paradigm triumphalism which held that there's only one path to God.

The idea of Deep Ecumenism wasn't Reb Zalman's alone. Centuries ago, Meister Eckhart wrote that "Divinity is an underground river that no one can stop and no one can dam up." Following on Meister Eckhart's teaching, Reverend Matthew Fox wrote "we would make a grave mistake if we confused [any one well] with the flowing waters of the underground river. Many wells, one river. That is Deep Ecumenism." Deep Ecumenism teaches that no single religious tradition is "The" way to reach God.

Reb Zalman built on that thinking when he wrote (and taught and spoke, time and again) that each religious tradition is an organ in the body of humanity. Our differences are meaningful, and our commonality is significant. No single tradition is the whole of what humanity needs; no single tradition contains all the answers. And that's great! Because it means that we can learn from and with each other across our different traditions. "The only way to get it together, is together."

Deep Ecumenism teaches us that we can best serve the needs of all humanity when we not only respect other religious paths, but collaborate with them in our shared work of healing creation. No one tradition contains all the answers, but every tradition can be (in the Buddha's words) "a finger pointing at the moon," directing our hearts toward our Source.

Reb Zalman z"l taught that we can and should find nourishment in traditions other than our own. No single spiritual path contains all of the "vitamins" that are needed. He wrote that we must undertake "the more intrepid exploration of deep ecumenism in which one learns about oneself through participatory engagement with another religion or tradition."

In engaging with the other, we learn about ourselves. When we learn from and collaborate with fellow-travelers on other spiritual paths, our own practices are enriched — and we come one step closer to a world without religious prejudice or fear.

(That's from the Deep Ecumenism page on the new ALEPH website.) This is one of the things I've always loved about Jewish Renewal. Reb Zalman's teaching that each religious tradition is an organ in the body of humanity -- each necessary; each individual and different; and each needing to be in communication with the others because we're all part of the same great whole -- speaks to me. And I think that this kind of shift, in interreligious relations, is something that humanity needs.

Over the course of 2015, ALEPH will be presenting a variety of programs relating to Deep Ecumenism. One will be a weekend gathering over the 4th of July in Philadelphia, titled GETTING IT TOGETHER: Reb Zalman’s Legacy and The Jew in the Lotus 25th Year Retrospective. (I'm incredibly excited about that; longtime readers may recall that Rodger Kamenetz's The Jew in The Lotus is the book which introduced me to Reb Zalman and to Jewish Renewal in the first place!)

Another will be a week-long retreat at Ruach Ha'Aretz (ALEPH's mobile summer retreat program) focusing on Deep Ecumenism. I know that some terrific Jewish Renewal teachers will be there, and the organizers are also exploring having teachers from other religious traditions as well. A third will be an interfaith pilgrimage to Israel and Palestine [pdf], to be co-led by Rabbis Victor and Nadya Gross, among others. And there are other projects in the works -- literary, liturgical, and so on.

When I think about why I'm glad to be on the ALEPH board of directors; when I think about the kinds of things ALEPH is doing which feed my spirit, and which I think have the capacity to be world-changing; this Deep Ecumenism work is one of top things on my list. This is one of the reasons I came to ALEPH in the first place -- because I found Reb Zalman's mode of interacting with, relating to, and learning from other traditions (as described in The Jew in the Lotus) to be so meaningful.

I'll post more about that 25th anniversary gathering as more information becomes available, but for now -- save the date, and consider joining us that weekend? I know that many of the original participants in that journey will be joining us, among them Rabbi Yitz and Blu Greenberg, Rabbi Moshe Waldoks, and of course Rodger Kamenetz himself. And it will take place on the Gregorian anniversary of Reb Zalman's leaving this life -- a sweet time to remember his work, and to rededicate ourselves to carrying that work forward in the world.

Va'era, freedom, and Reverend Martin Luther King

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul for parashat Va'era. (At least, this is the script from which I spoke. Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

Here's the d'var Torah I offered yesterday at my shul for parashat Va'era. (At least, this is the script from which I spoke. Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

God spoke to Moshe saying: go and tell Pharaoh, King of Egypt, to let the Israelites depart from his land. (Exodus 6:10)

This week we move deeper into our people's central story: we were enslaved to a Pharaoh in Egypt, and God brought us out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. This year, our reading of this holy story falls on the weekend when we prepare to observe Martin Luther King Day.

The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr -- alav hashalom / peace be upon him -- was a man in the mold of Moses. He worked tirelessly to end the injustice of segregation. He led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott. He organized nonviolent protests in Birmingham, Alabama, which attracted national attention because television crews captured the brutal police response. He dared to dream of a world redeemed in which the evils of racism would be a thing of the past.

As Jews, we twice a year recount the story of how we were slaves to a Pharaoh in Egypt -- during the weekly round of Torah readings, and at the Passover seder. We also thank God for our liberation from slavery in daily prayer and in the Friday night kiddush.

Our liberation is spiritual, not literal. None of us here today were actually slaves in Egypt. And many of you have heard me say before that it doesn't matter to me whether or not that story is historically true. What matters is that it's the story we tell about who we are.

But for Martin Luther King, the story of liberation wasn't about freedom from internal constriction, the "narrow places" in our lives or in our hearts. His ancestors were slaves to plantation owners and overseers in the American South. Not in the mythic mysts of ancient history, but a short few hundred years ago. And the unthinkable injustices of that system which treated Black human beings as subhuman chattel have not yet been wholly rooted-out.

Because stop-and-frisk policies disproportionately target Americans of color -- in New York City, 80% of those pulled over by police are people of color; and of those pulled over, only 8% of Whites are frisked, compared with 85% of Black and Latinos.

Because according to a study done by ProPublica, Black Americans are twenty-one times more likely than white Americans to be shot by police.

Because African Americans are incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of whites. And the U.S. Sentencing Commission reports that in the federal system, Black offenders receive sentences that are 10% longer than White offenders for the same crimes.

Because one in ten Americans still believes that businesses should be free to refuse service to African Americans... and, for that matter, to Jews. But although Jews have faced discrimination over the millennia, in this nation, today, we enjoy unprecedented acceptance. And those of us who are or appear White experience privilege which is denied to our Black sisters and brothers.

I'll let Ta-Nehisi Coates offer us the overview:

Having been enslaved for 250 years, black people were not left to their own devices. They were terrorized. In the Deep South, a second slavery ruled. In the North, legislatures, mayors, civic associations, banks, and citizens all colluded to pin black people into ghettos, where they were overcrowded, overcharged, and undereducated. Businesses discriminated against them, awarding them the worst jobs and the worst wages. Police brutalized them in the streets. And the notion that black lives, black bodies, and black wealth were rightful targets remained deeply rooted in the broader society.

It's an awful litany, isn't it?

The injustices against which Reverend Martin Luther King worked so tirelessly are not yet behind us. There may no longer be "whites only" signs on buses and water fountains, but racism and inequality persist in a million subtle and systemic ways.

And in the wake of a police officer's killing of unarmed Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO -- and the ensuing violence we have seen directed at peaceful protestors there and around the country in recent months -- we know that the violence with which Reverend King's peaceful protests were met is also not yet a thing of our nation's past.

In our Torah portion, when God tells Moses to go and tell the Israelites that freedom is coming, they can't hear his message of hope because their hearts have been crushed by bondage. I know that the hearts of many Americans of color have been crushed by the bondage of racism, both hidden and overt. I know that the work to which Reverend Martin Luther King dedicated his life is not complete.

But our tradition has something to say about unfinished labor. In Pirkei Avot, a collection of rabbinic wisdom, we read the saying of Rabbi Tarfon: it is not incumbent on us to finish the task, but neither are we free to desist from it. We can't stop trying; we can't give up hope. It was Martin Luther King who wrote that "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice." Aleinu -- it's up to us -- to help to see that vision through.

As we remember Reverend Martin Luther King this weekend, may we be galvanized to follow in his footsteps. To work tirelessly for justice. To overcome systemic racism in our nation -- and, since we who are hearing this today in this shul are white, I want to add: to educate ourselves about the realities our Black sisters and brothers face, and to eradicate racism in ourselves. It's up to us to build a future in which our grandchildren will find tales of early 21st-century American racism as unimaginable as we find our nation's history of slavery.

That's how we can honor the memory of a great man, a tzaddik in his generation. And that's how we can honor the liberation narrative at our people's heart.

January 14, 2015

Channeling smicha for the first time

I wrote recently about three ineffable moments from late last week -- visiting the prayer space where Reb Zalman z"l used to daven, leading prayer with my friend Rabbi Evan Krame, and savoring the davenen on Shabbat morning at the Shabbaton (Shabbat retreat) preceding the ALEPH ordination programs' smicha (ordination) ceremony and the OHALAH conference. But Sunday was ordination day, and it was more intense, more powerful, and more beyond-words than any of those.

On Sunday I got to do something which brought me more joy than I know how to describe. On that day, my beloved friend David became Rabbi David Markus. And at the moment of the rabbinic smicha -- the laying-on of hands and the speaking of the holy words which transform a student into a rabbi forevermore -- because I had been one of his teachers, I was privileged and honored to be able to be one of the people who stood behind him, through whom the words and the transmission flowed.

Along with others among our teachers and colleagues, I placed my hands on his shoulders. He closed his eyes and leaned back into our hands. And we called forth the words which created the change. In English, some of them are these:

Herewith we ordain you

To officiate as rabbis in Israel,

To publicly teach Torah,

And to clarify and pronounce truth in ways

that make a tikkun for the Shekhinah.

We hereby appoint you as delegates and emissaries

just as those who appointed us

delegated us and sent us to be rabbis...

May your hands be like ours

Your decree like our decree

Your rabbinic acts, valid like ours...

They are awesome words. Awesome in the original sense of that word; they awaken awe in me. Ever since the first smicha I ever attended, every time I hear them they go straight to my core.

It was only four years ago that I stood in front of my community, leaned back into the loving hands of my teachers, and took in the transmission of their blessing and their energy. I remember how it felt to receive that. I remember how it felt to walk around afterwards, my spirit buzzing and tingling, my heart as wide-open as the Colorado skies, feeling as though my spiritual DNA were being rewritten. And this time I got to be one of the channels for that transmission, that blessing, that change.

And then I got to look into the eyes of one of my dearest friends, who has been an integral part of my life for well more than twenty years -- who in college gave me the Rodger Kamenetz book which set me on the path to finding Jewish Renewal; who gave me my tefillin when I turned thirty; who took my advice and enrolled in a Jewish Renewal training program even though he wasn't certain where the path would lead; who has been my hevruta and my brother and my friend -- and call him Rabbi.

Naming him Rabbi felt as though something fundamental were snapping into place. Of course, it's transformative speech, like saying "I do" -- the words create change in the world. But it wasn't just the words. It was also the touch, the press of hands, the honored teachers clustered behind and around, their love and intention flowing through me along with my own. Serving as a channel for the transmission of smicha reminded me spiritually of birthing: something coming through me.

ALEPH's smicha ceremony always brings me joy. And every smicha I've attended since my own has reminded me of my own, and has strengthened my sense of smicha. (It's like the way that going to a good wedding reminds me of my own -- or, as I've heard my Christian colleagues say, the way every baptism invites the adults present to renew their own baptismal covenant.) But this year was different. This year the joy was multiplied: a hundredfold, a thousandfold, I can't quantify it.

This year, when I helped to confer smicha on my dearest friend, I also changed myself. I became not only a recipient of this incalculable gift, but also a transmitter. Not only someone who has received, but also someone who's opened a space so the gift can flow through me into others. And then there are the particularities of the two of us. He led me here, I led him here in return. I had the indescribable privilege of channeling smicha for him, and in return he enabled me to grow even deeper into my own.

I can't quite grasp words to explain how that felt, how it still feels. Can you imagine hearing music -- maybe the songs of the angels on high -- which, once heard, leaves you forever changed? Can you imagine the upwelling joy of the harmonies, soaring and uplifting, the way your heart would brim over with gratitude and surrender? Can you imagine how you might feel in the silence after the song, the harmonies lingering long after the melody has faded from the air?

January 13, 2015

Ruth Messinger on tikkun olam at OHALAH 2015

The theme of this year's OHALAH conference is "Integral Tikkun Olam." One of the keynote speakers is Ruth Messinger, the head of the American Jewish World Service. Here are some glimpses of the latter part of her Monday morning keynote.

As I enter the room -- having unfortunately missed the first hour of her address; apologies for not being able to blog her earlier remarks -- Ruth is talking about Burma. (Which is intriguing to me in part because Ethan was there relatively recently and it's a place in which I am personally interested, and also because I'm not sure I've ever heard Burma discussed in a Jewish communal setting.)

In Burma, she tells us, Muslims are in danger from fundamentalist Buddhists. (A ripple runs through the room when she says that. She notes tartly that Jewish groups often struggle with this one. Clearly our communities have some prejudices which we need to recognize and overcome.) While the current government is better than the previous, things are still not good for minorities in Burma.

The addition of a little bit of democracy, she says, can sometimes make it more possible for people to turn on each other. There are huge efforts to protect the Rohyinga Muslim population; there was a successful Twitter hashtag campaign called #justsaytheirname, designed to bring pressure on President Obama when he was there recently, to mention them and ask about their future.

@ajws Great update - see it live on Voice Rohingya: http://t.co/9D3ihiIBNR

— Voice of Rohingya (@VoiceRohingya) November 13, 2014

(She also noted that oppression can take many forms; the Burmese government is taking a census, and has instructed their census-takers to ask what religion people are and if they say Muslim, not to count them.)

Then she shifts focus from Burma to violence against women. "A huge piece of our work," she says, "our biggest current campaign, is the #WeBelieve campaign, to address the global epidemic of violence against women and girls."

She tells a story about Teresa, in Nicaragua, who married at nineteen and had six children. "For thirty years, Teresa suffered physical abuse at the hands of her husband," Ruth tells us. "She had no idea who to turn to or what possible help there could be for her. And then a few years ago her oldest daughter told her that her husband was molesting their daughters as they came of age. Teresa and that daughter then spent two years conspiring to never leave the younger girls alone with him, but she had no place to go."

"And then one day she listened to the radio, a powerful tool in the global South, and heard an ad from AMEWAS, one of AJWS' grantees, which is dedicated to educating women and girls about their rights and to expanding womens' access to the judicial system. Because of this one radio ad, Teresa went to her brother and decided to leave her home." She took her children, went to the AMEWAS shelter, and they supported her in pressing charges against her husband and in 2011 he was sentenced to years in prison. AMEWAS then worked in a precedent-setting case to transfer possession of their property to Teresa.

"We have many Teresas," Ruth says. "We have many partner organizations and many stories. And we share the stories so that people will see the human beings who are affected by our work, and understand that all of these are ways to make a difference."

"We are interested in debating with people the tensions that come up in our community -- the tensions between the local and the global, as if they were entirely disconnected; the tensions between the particular and the universal." People are often persuaded that they should do local, or that they should do global, but not that they should do both. But, Ruth argues, we live in an interdependent world. How we act locally can impact people elsewhere. What we do in Washington can make a dramatic difference for people tens of thousands of miles away.

Ruth mentions the International Violence Against Women Act, which will promote the dignity of millions of women and girls around the world; it has been introduced to Congress four times since 2005, and represents an unprecedented commitment by the US government to support the needs of women and girls... if Congress will pass it. (This has become one of AJWS' major campaigns - see We Believe.)

Ruth mentions the International Violence Against Women Act, which will promote the dignity of millions of women and girls around the world; it has been introduced to Congress four times since 2005, and represents an unprecedented commitment by the US government to support the needs of women and girls... if Congress will pass it. (This has become one of AJWS' major campaigns - see We Believe.)

She praises grassroots groups like AMEWAS who are doing work on the ground around the world, and notes that the IVAWA would make it more possible for women and girls to earn an income, to collect food and water without fear of harassment, to live without fear of rape and violence. If the IVAWA were passed, she says, "organizations like AMEWAS, of which there are thousands in the developing world, would finally get some of the funding and recognition that they deserve."

This act would provide public education campaigns. It would allow the US government to raise the question of the prevalence of gender-based violence in all of its negotiations with any country, and would require us to raise it in our dealings with countries where the problem is most significant. "It would move this crisis of violence against women and girls from being an invisible source of shame to being a public issue which governments are working to solve."

"Don't laugh," she says, "but we have a new Congress." Rueful laughter runs around the room; how many of us believe that Congress is actually capable of creating positive meaningful change? "At this moment in time, any piece of legislation which mentions women is assumed by some in Congress to have something to do with abortion," she notes, "so even though IVAWA absolutely does not, that poses a challenge... But there are members of Congress who are supporting this work, including many female Jewish members of Congress." (That draws a cheer from the crowd.) Working on IVAWA is an uphill climb, but it matters.

Ruth urges us as Jewish Renewal clergy to think, speak, and act globally; to care about people far beyond our borders, whatever our borders may be; to learn about the needs and struggles of people around the world, to share their stories; to help AJWS not only identify the policies which need change but also the legislators who need help relating to parts of the world to which they have been persistently blind. And she urges us to think about getting engaged in the IVAWA effort and the WeBelieve effort and in the ongoing work they are doing with the support of the American Jewish community.

She closes with a quote from Grace Paley: "the only recognizable feature of hope is action." Let's act for women and girls, for indigenous people, for those around the world who are suffering the worst ravages of oppression and injustice. It's our mandate as Jews, and it's the legacy we can carry forward into the future together.

January 11, 2015

Remembering

Today is ordination day.

I'm remembering the first smicha ceremony I ever witnessed, nine years ago, when I was new to the ALEPH ordination programs.

And I'm especially remembering my own ordination, four years ago:

...And then the seven rabbinic candidates are called forth beneath the chuppah to stand in front of our teachers.

Someone murmurs "lean back," and I do. I can feel Reb Laura's hands on me, and Reb Sami's, and the weight of the va'ad and the other teachers standing with them all clustered together holding us up. Are they leaning on us, or are we leaning on them? I close my eyes; the world feels too luminous. It's like the period when I was birthing Drew; the doctor invited me to look in the mirror and see him emerging, but all I could do was close my eyes and go inside to be present to what was unfolding...

I can't wait to hear the Torah which I know today's candidates for smicha will give over. I can't wait to celebrate my friends and beloveds as they take this leap and are transformed into something new.

January 10, 2015

Ineffable

It is difficult to describe the experience of entering into Reb Zalman (z"l)'s prayer room. Parting the curtains, entering a little cave filled with prayer books and holy items and meaningful photographs. Sitting in one of the chairs facing his empty seat. Gazing at the items on the table -- the small keyboard, the little velvet pouch -- and feeling as though I had entered into a still life painting. Or as though I were in Pompeii, some vital and vibrant place where everything just stopped. Nothing has been moved. It feels as though he could have just been here, as though I just missed him. The room vibrates. The moment I sit down in the chair I burst into tears, so sudden and intense that I am surprised by their presence. I think: this is how a place becomes holy -- when someone sits here and prays, day after day after day; when visitors come seeking teaching and counsel, year after year; when hope and heart and tears and love are poured into a place so intensely that they leave an imprint.

2. Friday

It is difficult to describe the joy of leading davenen with a dear friend. Leading a community of a couple dozen ALEPH board members, all of whom we know well, all of whose voices are dear to us, all of whom know the flow of the prayers as intimately as we do. Beginning with the "Cowboy Modah Ani" (which has never felt so perfectly appropriate as it it does in Colorado.) Starting R' Hanna Tiferet's "Ashrei" round, and having everyone in the room not only sing along but also spontaneously take up the round, as R' Shefa Gold drums. Invoking (and imitating) the angelic choirs while singing "Holy, holy, holy." (Soon-to-be) Rabbi Evan Krame singing the Mi Chamocha prayer of redemption to the melody of a Zulu hymn, a test run for Shabbat. Me singing spontaneous prayers on the themes of the thirteen "request" blessings of the weekday Amidah. Closing with riotous laughter as we honor the snowy landscape outside by singing "Adon Olam" to the melody of "Winter Wonderland."

3. Saturday

It is difficult to describe the joy of Shabbat morning services with some two hundred people, many of whom are known and beloved to me. The service led by people I know and love. (Soon-to-be) Hazzan Daniel Kempin playing his guitar. Singing the hymn Siyahamba in Zulu, and then in Spanish, and then Hebrew, and then German, and then English -- "We are walking in the light of God!" -- which transitions seamlessly into into Mi Chamocha, the song of our redemption at the Sea of Reeds, when we walked in the light of God from slavery into freedom. Dancing in the aisles, feeling tears of joy prickle the back of my eyelids as we shift to "We are singing in the light of God" and finally "we are praying in the light of God." Hearing (soon to be) Rabbi David Markus' extraordinary d'var Torah about Moshe at the burning bush, and chaplaincy, and "rookie moves," and how our times of turning away can become inflection points in our spiritual paths. The harmonies. The heart. The joy.

January 7, 2015

ALEPH and OHALAH in Colorado: reuniting with my hevre again

I'm on my way today to Colorado. I've been going there at this time of year since I started the ALEPH rabbinic program, which is when I became a student member of OHALAH (the association of Jewish Renewal clergy) and began attending the OHALAH conference and the Shabbaton which precedes it. (The ALEPH ordination programs hold our smicha ceremony on the Sunday afternoon in between that Shabbat retreat and the conference proper.)

I'm on my way today to Colorado. I've been going there at this time of year since I started the ALEPH rabbinic program, which is when I became a student member of OHALAH (the association of Jewish Renewal clergy) and began attending the OHALAH conference and the Shabbaton which precedes it. (The ALEPH ordination programs hold our smicha ceremony on the Sunday afternoon in between that Shabbat retreat and the conference proper.)

Usually I head out in time for Shabbat, or in time for the ordination. This year I'm going a few days earlier than in years past, because now I serve on the board of directors of ALEPH: the Alliance for Jewish Renewal, and the ALEPH board meets in person before the OHALAH conference every year. We meet via teleconferencing every month, but I was only able to be tele-present for our summer retreat in Oregon, so I'm looking especially forward to being part of this board gathering in person.

I'm especially excited about davening with everyone (we'll begin our board meeting days with shacharit, morning services, co-led by different board members each day) -- meeting our new Executive Director Shoshanna Schechter-Shaffin in person for the first time -- conversations about the Deep Ecumenism programming we'll be sharing over the course of 2015 -- and to the rejuvenation of my Jewishness which always happens after sustained time with my Jewish Renewal hevre.

Of course, this will be our first winter gathering without Reb Zalman z"l. Many of us came together in August for the Remembering Reb Zalman Shabbaton and memorial, but I know that it will still be strange to be there without him. Like a giant family reunion without our beloved grandparent. Even though he had been stepping back in recent years, he's the one who brought us all together in the first place. I'm not yet used to the reality that he's no longer here, that his legacy rests in our hands.

I dreamed a few nights ago that I was at a summer camp, and it was Friday night, and I went to the theater and found that there was davenen there. I slid into the back row because I was running a bit late, and saw that Reb Zalman z"l was sitting in the row in front of me, merrily singing along. I knew, in the dream, that he was sitting in the back (instead of in his customary front-row seat) because he didn't have the energy to be his usual front-row presence, but he was happy to be with us.

Wishful thinking? Sure, maybe. But to me it felt like a clear sign that his presence will be with us when we gather this week for Shabbat and for the smicha ritual on Sunday. From the back row, as it were, because he's left the role of the rebbe's chair behind -- but I think we'll feel his loving presence with us as we sing and celebrate, and especially as ordain the next links in the chain of our lineage which connects us back with him and with generations of sages and teachers in our tradition.

To all who are joining me in Colorado today, or Friday, or Sunday -- I wish you smooth travels and a gentle landing!

Image: license plate which reads "Sh'viti," a reference to a line from psalms ("I have placed God before me always") -- photograph taken at last year's OHALAH conference.

January 6, 2015

Shabbat, technology, and tube socks

It really wasn't my intention to base multiple Hebrew school lessons this year around repurposed undergarments. But sometimes this rabbinic life takes me into places I didn't exactly expect to go. Case in point: yesterday I found myself preparing for my fifth-through-seventh-grade class by standing in line at the local Dollar Store (not my favorite shopping destination, but this time it was suitably affordable for my needs) with a double armful of cheap white tube socks.

I wanted to teach my students about Shabbat. I knew I wanted to begin with a short conversation about who creates holiness, God or us. (Psst: both, together.) I knew I wanted to convey that Shabbat is the holiest day of the year and it happens each week; that on Shabbat, we who are made in God's image rest as Torah teaches that God rested on the seventh day of creation; that Shabbat is a day to stop doing and to just be, to be "human beings" instead of "human do-ings."

In years past, I haven't been wholly satisfied with our conversations about different Jewish ways of understanding the commandment to rest and not do work. One year I taught a lesson about the 39 forms of labor which are traditionally understood to be prohibited on Shabbat, but it was hard to connect those to my students' lived experiences. It's too easy for them to start seeing Shabbat practices as deprivations, instead of as opportunities for connection, holiness, a different state of mind.

I know that most of my students have cellphones. And I'm pretty sure that if I suggested to them that they turn off their phones every Shabbat, they would balk. (As might their parents.) What I wanted instead was to get them thinking not about whether they use technology on Shabbat, but how they use it. For instance: is there a difference between using one's phone to call a friend and connect, vs. using one's phone to play a solitary game which keeps one disconnected from the world?

If nothing else, I thought there might be some interesting fodder for conversation.

So I decided to make and decorate cellphone bags. Not with an eye toward shaming my kids for using their phones on Saturdays, but with an eye toward shifting how they use those phones on that special day. (And even if they don't actually use the bags most of the time, maybe the act of making them would be a consciousness-raiser.) The challenge was, I don't have a very large education budget, and I didn't want to spend money on fancy cellphone cases which I wasn't even sure the kids would use.

Enter the tube socks.

Here is the demo version I made before class to show them how the project might look.

We began the class by talking briefly about holiness and how both we and God make things holy. I offered some teachings about Shabbat and what makes it special. We brainstormed what it might mean for them to "not work" on Shabbat -- "to not do my chores," one suggested; "not cleaning my room;" "not doing homework" -- and then I shifted into talking about other ways of understanding that commandment, including the practice in many Jewish communities of eschewing electricity use.

We were briefly sidetracked into a conversation about cooking, because a few of my students had never heard of the idea of not cooking on Shabbat. Some found it fascinating; others thought it sounded gross. (Though one student who attends Jewish summer camp exclaimed "Oh! That's why we always have cold sandwiches on Saturdays!" It was gratifying to see that lightbulb go on.) And then I pointed out that using our technological devices, like cellphones, constitutes electricity use.

"I spent a whole day without using technology once," one kid volunteered. "It was awful!" Agreement rippled around the table. As the boys in particular started agreeing vociferously that a day without video games sounded like punishment, I started asking the questions I posed above -- is there a difference between using a phone in a solitary way and using it in a connective way? For instance, is it Shabbat-appropriate to use one's cellphone to say something unkind about someone else?

Is there a difference between using one's cellphone for gossip (which we know can be spread in unretractable ways -- there's the parable of the person who comes to the rabbi seeking a way to make amends for gossip; the rabbi tells them to cut open a pillow and let the feathers blow away, and then notes tartly that it would be easier to gather those feathers than to undo gossip once it's spread on the winds of conversation) vs. using that same phone to call someone and express kindness and caring?

Is there a difference between using one's phone as a way to keep other people at bay (playing videogames instead of actually talking with family), vs. using one's phone as a way to connect with other people via voice or text -- either those in the room, or those whom we love but who are far away? Maybe I asked the questions in a leading manner, but they all seemed to get the point I was making. Technology can alienate us, or it can connect us. Shabbat is a day to seek connection.

And then we decorated cellphone bags. Everyone's bag says שבת שלום on it (and some also say "Shabbat Shalom" in English.) Some wound up adorned with flowers, or stars of David, or stripes and patterns. I have no idea whether or not the kids will actually use them this weekend. But I hope that perhaps making them will be memorable. Maybe it will plant a seed in the back of their minds which could someday flower into a Shabbat practice of mindful technology use.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers