Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 135

February 18, 2015

Terumah: the Torah of 40

Here's the d'var Torah I had intended to offer yesterday at my shul. As it turned out, I touched on a few of these ideas and then went in a different direction, as we were davening at the local nursing home, but I hope you'll read the prepared text anyway.

God spoke to Moshe saying: tell the children of Israel that they should bring Me gifts...from every person whose heart is so moved.

This week's Torah portion, Terumah, begins with this instruction to bring gifts for use in the construction of the mishkan, the portable sanctuary intended to be a dwelling-place for God. Terumah, the name of the Torah portion, is usually translated as "gifts."

Earlier this week I studied a Hasidic text written by the grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, Rabbi Moshe Chaim Ephraim of Sudilkov. In his book the Degel Machaneh Efraim, he offered a fascinating interpretation of the word terumah.

Terumah, he said, can mean more than simply gifts. The word terumah can be deconstructed, the letters rearranged, into תורה מ / "Torah Mem" -- the Torah of forty. (Remember, Hebrew letters double as numbers.)

Torah was revealed atop Sinai over 40 days, he writes -- just as a human being, in ancient rabbinic thought, achieved its form in the womb over a period of 40 days. He's drawing on a longstanding rabbinic interpretation which connects the number 40 with the time it takes for something to go from beginning to fruition. The rabbis also taught that 40 are the days between planting and harvest, and 40 are the weeks between conception and birth.

So Torah comes to us through 40 (days), and a human being comes to us through 40 (either days or weeks.) What happens if we re-read the opening lines of this week's Torah portion through this lens?

God spoke to Moshe saying: tell the children of Israel that they should bring Me the Torah of completeness and fruition; the Torah of every human being.

Human beings and Torah both require 40 units of time to emerge into this world. Ergo, each person is a Torah! This is a radical teaching, because in Hasidic thought the Torah is the most valuable thing imaginable -- it's a direct transmission of God's essence.

Later in this week's Torah portion we read:

Let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell within them.

What can it mean to say that God dwells within us? The Degel teaches that that we bring God into ourselves when we study Torah, because Torah is one long and complex Name of God.

"God and Torah are one," says the Zohar -- so if we study Torah, and bring Torah into ourselves, then we are also bringing God into our hearts. The Zohar also teaches that God, Torah, and Israel are one, which is to say: we, and God, and God's Name as expressed in Torah, are all part of the same unity. In the language of the Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, we and Torah and God "inter-are."

The gifts we're called to bring before God are gifts of ourselves; gifts of our own completeness; gifts of new creation which only we can bring. The root of the word terumah is רם, which connotes raising something high. When we understand that we, and God, and Torah "inter-are," then we can bring our most unique personal gifts, and in so doing be elevated to the highest of spiritual planes. May it be so!

My infinite thanks are due to my hevruta partners Rabbi David Markus and Rabbi Cynthia Hoffman for translating this text with me, and especially to R' David for helping me tease out its deeper spiritual implications.

If the idea of "inter-being" is new to you, read this tiny excerpt from Thich Nhat Hanh -- from his book The Heart of Understanding, which R' David and I also studied together some 25 years ago!

February 16, 2015

Mindful speech

The Christian season of Lent is almost here. I know that many of the Christians I know online choose to use this season as a time to "fast" from particular qualities or forms of internet use -- fasting from Facebook or Twitter, for instance, and using the time they would otherwise have spent on social media in prayer or contemplation. Yesterday I saw a reference to such a practice online. In response I tweeted that even those of us who don't celebrate Lent might consider thinking twice before we type.

Even if you don't observe Lent... MT @mtjofmcap try thinking twice before typing something snarky or narrow-minded.

— R' Rachel Barenblat (@velveteenrabbi) February 16, 2015

Some do this during Elul too. I like the idea of moderating tone rather than departing the internet altogether. @JYuter @mtjofmcap

— R' Rachel Barenblat (@velveteenrabbi) February 16, 2015

Rabbi Josh Yuter asked what I meant by moderating tone. I found myself quoting Rabbi Harry Brechner's threefold rule: "Is it true? Is it kind? Is it important?" (I wrote about that in my 2013 post To shame someone is to shed their blood, about the "emerging Gemara" of ethical internet behavior.) In turn, R' Yuter noted that outrage is rarely kind. He has a good point. Our broken world demands justice, and sometimes the need to pursue justice may trump my desire to cultivate kindness.

And, at the same time -- I've found that when I give too much energy to justice and not enough energy to kindness, my soul doesn't flourish. Kabbalah teaches us that God's qualities of chesed (lovingkindness) and gevurah (boundaries / strength) need to be kept in balance. Too much of either one isn't good for creation. I wonder whether each of us has a subtly different balance of healthy chesed and gevurah in our hearts and souls. My heart definitely calls for leaning toward kindness.

I read a powerful article in the New York Times recently -- How One Stupid Tweet Blew Up Justine Sacco's Life. (If you haven't read it yet, I recommend it.) There are countless upsides of this interconnected world. One of those upsides is that we can use social media to create positive change. The shadow side is that sometimes we cause harm. We have new ways of hurting each other. Careless statements made online can be shared around the world in incredibly destructive ways.

Most religious traditions preach the importance of moderating one's speech, and Judaism is no exception. In Mishlei (Proverbs) 10:19 we read, "Where there is much talking, there is no lack of transgressing, but the one who curbs the tongue shows sense." And in Pirkei Avot 6:6, moderation in speech is listed as one of the 48 qualities through which one acquires Torah, which can mean something like accessing deep wisdom or accessing flow of blessing from the divine.

As a poet and a liturgist, I try to take language seriously. With our words we can create worlds -- and we can also shatter them. I can always use a reminder to pay attention to what I say and how I say it, both online and off. (And when we reach the period of the Omer, the 49 days we count between Pesach and Shavuot, I might follow Mussar practice and try to cultivate those qualities from Pirkei Avot 6:6 each day -- including moderation in speech, which for me includes what I signal-boost and retweet.)

One rubric I sometimes use is: whatever I'm about to say, would I be comfortable saying it where my teachers could hear me? I have a particular group of teachers in mind -- but it could be your parents, your children, your sensei: someone(s) in your life whose opinion you value. For those of us who cultivate a personal relationship with God, that's another way to make the decision: if you were called before God tomorrow, would you feel glad about this remark, or would you regret having said it?

I'm as prone as anyone to the Someone is wrong on the internet syndrome -- and sometimes my desire to correct all of those wrong people does me no favors. But I'm trying to train myself to pause and to be thoughtful. Over the years I've trained myself to click into the groove of the morning prayer of gratitude, as close to the moment of waking as I can manage. I'd like for kindness and thoughtfulness to be the same kind of reflexive acts, so innate that I don't even have to instigate them any more.

New moon is coming

I awoke recently in the night and saw the enormous icicles hanging down from our bedroom windows limned by moonlight. All I could think in my sleep-muddled state was that we were surrounded by an icicle forest! But the moonlight shining on our icicles has been decreasing. Right now the moon is waning away to nothing. And once it reaches nothing, it will begin its monthly rebirth.

I awoke recently in the night and saw the enormous icicles hanging down from our bedroom windows limned by moonlight. All I could think in my sleep-muddled state was that we were surrounded by an icicle forest! But the moonlight shining on our icicles has been decreasing. Right now the moon is waning away to nothing. And once it reaches nothing, it will begin its monthly rebirth.

It's been too cold in New England for outdoor stargazing, but if I had been outdoors the last few nights I would have seen increasing numbers of stars. When the moon is big, she drowns out some of the complexity of the night sky. But when the moon wanes, more stars become visible to the naked eye -- tiny pinpricks of light which don't add up to the moon's brilliance, but they're beautiful nevertheless.

In Jewish tradition, every new moon heralds a new month. When the moon begins to grow again in a few days, we'll enter into the month of Adar. "When Adar enters, joy increases," goes the saying -- this is the month which contains Purim, our joyful festival in which we celebrate not only our people's survival in the face of a terrible tyrant (what else is new) but also life's topsy-turviness in general.

I've been thinking about what kind of joy I'd like to see increase as Adar rolls in. I have friends and loved ones who've undergone surgery recently; I hope that Adar will bring them healing. I know that people are grieving recent terror attacks (on Jews in Copenhagen; on Muslims in Chapel Hill); I hope that Adar will bring them comfort. For me -- I'm hoping that Adar will bring early stirrings of spring.

I'm not expecting warmth, not here -- right now this is a land of giant snowdrifts and six-foot icicles. But every day there is just a little bit more daylight. And in two more weeks when we reach Purim, the secular calendar will flip over to March, and that always feels good too. Meanwhile, the best joy instructor I know is our five-year-old son. Maybe this is a good time of year for me to learn from him.

Rosh Chodesh Adar will arrive on Thursday. For more on the meanings of Adar, try my 2013 post Happy Adar!

February 15, 2015

Mishpatim: the angry ox and the Chapel Hill shooting

Here's the brief d'var Torah I offered at my shul yesterday morning. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

In this week's Torah portion we receive a wealth of ethical commandments.

In this week's Torah portion we receive a wealth of ethical commandments.

For instance: When an ox gores someone to death, kill the ox, but don't punish its owner. But, if the ox has been in the habit of goring, and its owner knows that but fails to guard it, and it gores someone to death -- then punish its owner, because the person who had responsibility failed to act.

I've read this verse many times before. But this year I couldn't help reading it through the lens of the news story I've been following this week.

A few days ago in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, a man entered the apartment of two neighbors and shot the couple and the woman's younger sister in the head, execution-style. He later turned himself in and claimed that he killed them over a parking dispute.

The three young people who were murdered were Deah Shaddy Barakat, Yusor Mohammad, and Razan Mohammad Abu-Salha, aged 23, 21, and 19. Deah and Yusor were newlyweds, married in December. They were dentistry students who donated their dental expertise to the local homeless community, taught kids about dental hygiene at the local library in their spare time, and raised money and dental supplies to take to Turkey so they could help Syrian regufees. Razan was a college kid, a student of architecture and environmental design. All three of them were pillars of their community. Deah, Yusor, and Razan were Muslim.

This act would be atrocious no matter who the victims were. But it is extra-heartbreaking to me because they were so young, and so idealistic, and so full of life.

The man who killed them was a known anti-theist -- not merely an atheist, but someone who loathed religion. He had posted nasty anti-Muslim language on Facebook. He had harassed these victims before. The young married woman had told her father, "He hates us because of who we are."

What he did was beastly. And when I read the verses about the ox who gores someone to death, I think of this man who killed three innocent souls for reasons I cannot begin to fathom.

And then I wonder: who is responsible for the behavior of the ox? In the Torah, the answer is clear: its owner, if that owner had any suspicion that the ox would behave in such a way.

In Torah, it is also clear that we are to regard ourselves as our brothers' keepers. We are responsible for each other. Torah calls us to guide each other in lives of righteousness and to rebuke each other when needed. Granted, Torah is speaking in terms of the "us" of the children of Israel, the Jewish community. Torah presumes that Jews are obligated to take care of Jews.

But today our world is more pluralistic. We're part not only of the Jewish community, but also the American community. And many of us have connections to other religious communities, through marriage or friendship or affinity. In today's paradigm, Torah might teach that we all have a civic obligation to each other.

American culture, media, and stereotypes devalue the lives of Muslims and the lives of people of color. This happens in a million tiny ways and it is constant and omnipresent. I fear that this persistent devaluing of these lives teaches us, subconsciously, that these lives have lesser value.

I don't know whether this massacre could have been prevented. But I believe that an American culture of fear and suspicion of Muslims contributed to this killer's willingness to shoot these three young Americans in the head in their own home. And I believe that if we don't act to change our nation's culture, there will be more killings like this one -- and all of us who sat idly by will be the ox owner who could have stopped the ox.

How can we change the culture of our entire nation? It's too big a task. But we can begin by teaching our children that we value diversity. We can teach them that the great thing about a world filled with people who look, dress, or worship differently than we do is that we can learn from and about each other -- we don't need to be afraid of each other.

We can begin by educating ourselves about the experiences of other people and other communities in this country. We can begin by expanding the circle of people about whom we care.

One of the reasons I care so much about this story is that people in my life care about it. On Wednesday morning as the news was breaking, I was home sick with a virus, and was in bed with my iPad. I watched, on Twitter, as my Muslim friends grieved these killings. I learned about the victims. I read Muslim responses to the awful news. My heart went out to my friends, and by extension to their whole community.

I came to care deeply about this story because people who are important to me cared about it. People with whom I have shared meals, prayer, conversation, togetherness. These killings impacted them, and because I feel connected with them, the killings impacted me.

Many of us in this room have that kind of relationship with Israel: we know people there, or we have family there, or we've visited there, or we feel connected with our fellow Jews there. So we pay attention to the news from there, and when there is death there we grieve. My husband Ethan has that relationship with Ghana: he's lived there, he has a deep network of community there, and because he cares deeply about West Africa, he's emotionally invested in what happens there.

It's easier to care about something -- a person, a place, a community -- when you have a personal connection. How can we grow our personal connections with communities beyond our own, so that when something like this happens to someone in another religious community, we feel it too?

We can begin by striving to teach ourselves to respond to difference not with fear or anxiety, but with kindness and compassion. The verse most oft-repeated in Torah is "love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt." For me, the place where this work always begins -- where it has to begin -- is with love.

February 13, 2015

Shabbat

This has been a week with more than its share of heartache. And I know that every week fits that bill for someone, somewhere.

This has been a week with more than its share of heartache. And I know that every week fits that bill for someone, somewhere.

Shabbat is supposed to offer us a taste of the world to come. A drink from the fountain of eternity. A stroll through the orchard of Eden where we can linger with the Beloved to our hearts' content.

I wonder how many of us will struggle to shed the week now ending when sundown falls tonight. Will we have a hard(er than usual) time setting workday, weekday, worldly worries aside?

Weeks like this one, I realize how truly radical the idea of Shabbat is. That no matter how broken the world, no matter how important the work, we are called to set it all aside tonight and be with our loved ones and with God.

No one can struggle all the time. Whether it's an external struggle against hatred and intolerance, or an internal struggle with burnout or depression -- we all need to be able to set our burdens down.

When I light candles tonight I will pray with all my heart for more light.

When I bless wine tonight I will pray with all my heart for the joy it represents.

When I bless our son I will pray with all my heart that every parent who grieves tonight be comforted.

May this Shabbat bring joy to our homes and balm to our hearts.

February 12, 2015

On the Chapel Hill shootings

The most heartfelt -- and heartbreaking -- piece I've read about the Chapel Hill shootings is this one: My best friend was killed and I don't know why. I commend it to you, along with this NPR piece -- 'We're All One,' Chapel Hill Shooting Victim Said in StoryCorps Talk:

"Growing up in America has been such a blessing," Yusor Abu-Salha said in a conversation with a former teacher that was recorded by the StoryCorps project last summer...

"There's so many different people from so many different places and backgrounds and religions — but here we're all one, one culture."

What a terrible shame it is that we are only getting to know these luminous young people on the national stage because they were shot in the forehead, execution-style, in Deah and Yusor's own home.

For my response to the killings of 23-year-old Deah Shaddy Barakat, 21-year-old Yusor Mohammad, and 19-year-old Razan Mohammad Abu-Salha, click through to The Wisdom Daily:

My first response to this news is grief. I imagine myself in the position of the parents of the victims, and my heart aches. I can only imagine what their families are going through. (Yusor and Razan were sisters - grief compounded.) Their deaths are atrocious. That would be true no matter who they were. But somehow, their murder is all the more horrifying because the victims were young, and idealistic, and by all accounts were trying to make the world a better place...

...[H]ad the shooter been Muslim, surely the headlines would have been emblazoned with "terrorism." But because the shooter was White and the victims were Muslim, this story gets reported as a "fatal shooting" or a "possible hate crime." Those covering the crime use softer words, as though they could make the reality any less terrible, and as though they could remove our own sense of guilt for living in a society where Islamophobia may lead to senseless violence...

Read the whole thing here: Shock in Chapel Hill - Should We Call It Terrorism?

I'm grateful to the editors of The Wisdom Daily for including me among their roster of contributors, and hope you'll click through and read. (Also, if you're on Twitter, consider following them - @WisdomDailyNews.)

February 10, 2015

Natural history of a world that never was

One of the things I frequently love about science fiction and fantasy is that it opens up the possibilities of worlds other than our own. In that sense it's a very redemptive genre, because it holds out hope that the way things are is not necessarily the only way they could possibly be.

One of the things I frequently love about science fiction and fantasy is that it opens up the possibilities of worlds other than our own. In that sense it's a very redemptive genre, because it holds out hope that the way things are is not necessarily the only way they could possibly be.

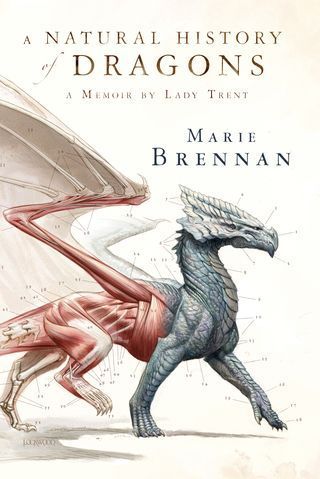

The most recent SF/F book I've devoured does this -- with a twist. The setting isn't futuristic, but the past, in a world which is clearly not this one but has enough in common with our own that the changes are striking. The book in question is Marie Brennan's A Natural History of Dragons: A Memoir by Lady Trent, which purports to be the illustrated memoir written by the woman who pioneered the study of those magnificent beings.

All the world, from Scirland to the farthest reaches of Eriga, know Isabella, Lady Trent, to be the world's preeminent dragon naturalist. She is the remarkable woman who brought the study of dragons out of the misty shadows of myth and misunderstanding into the clear light of modern science. But before she became the illustrious figure we know today, there was a bookish young woman whose passion for learning, natural history, and, yes, dragons defied the stifling conventions of her day.

Here at last, in her own words, is the true story of a pioneering spirit who risked her reputation, her prospects, and her fragile flesh and bone to satisfy her scientific curiosity; of how she sought true love and happiness despite her lamentable eccentricities; and of her thrilling expedition to the perilous mountains of Vystrana, where she made the first of many historic discoveries that would change the world forever.

(That's how the book is described on the author's website.) It's a pitch-perfect rendering of a Victorian memoir, with the most delightfully plucky and well-rounded heroine one could ask for. And -- you will probably not be surprised to discover that this is a part I thought was neat -- the book hints at a kind of alternate version of Judaism in this unfamiliar world. Or, actually, two versions. My first clue was the passing reference to Lady Trent having published her memoirs in 5658. That sounds like the Jewish way of counting time, not the Christian one. But that one detail wasn't enough to convince me that this world's alternate Judaism was intentional.

My second glimpse was when Lady Trent, offhandedly, mentions that the Vystrani pray and study scripture in Lashon, whereas in Scirland they use the vernacular. "Hm," thought I. "Lashon means 'The Language' in Hebrew. I wonder whether that's an intentional shout-out, or whether she just chose the syllables because they sounded nice." I shouldn't have doubted; everything else about the book is so thoughtful, of course Brennan made her imaginary linguistic choices intentionally. Sure enough, immediately after the reference to Lashon vs. vernacular, we learn that both variations of this world's dominant religious tradition make use of a "blessing at the end, with fingers divided," and that the blessings final words are "and bring you peace." If that's not the Priestly blessing, I'll eat my kippah.

Religious practice in Scirland and in Vystrana are not the book's primary theme. We catch glimpses of this world's religious life only insofar as it's relevant to the unfolding plot. There are two primary forms of the dominant religious tradition, one Temple / sacrifice-based and the other centered around study. In Vystrana the locals are highly concerned with purity, and require immersion in "living waters" when the visitors encounter a potential spiritual contamination. (Hello, mikvah immersion! That, in turn, reminded me of one time when I followed ancestral practice and immersed in an outdoor source of living waters before Yom Kippur...which was awfully cold, though not nearly as bad as what Isabella expriences.)

Also when the visitors encounter that contamination, the townspeople rush them with graggers, which Isabella notes she's only ever encountered before at a particular religious festival when the noisemakers are used to drown out the name of the villain, wicked Khumban. That festival will be Purim, in our world, which is coming up in just a few weeks, so that reference made me grin.

Part of what's delightful for me about this is that Brennan doesn't make any kind of big deal about Judaism (or variations thereupon) being central to the book. It's just part of the background, part of how Isabella processes the world around her. Brennan's written about her decisions to work with Judaism in these ways in a guest post at AlmaNews -- Marie Brennan on 'Natural History of Dragons.' See also Prodding the Defaults, episode 316. One of the things which can be frustrating about being part of a minority religious tradition, in our world, is that the imagery, iconography, and assumptions of the dominant tradition are everywhere, and no one questions that default setting. I enjoyed reading about a world in which traditions and practices are intriguing variations on my own, rather than variations on Christianity.

Anyway, it's a lovely book, and I'm already looking forward to the sequel.

February 9, 2015

The Zohar and the Force

"Its energy surrounds us and binds us," says Yoda to Luke Skywalker, describing the Force. "Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter!"

We've had a lot of snow days recently in New England. Snow days mean playing outside, sledding, hot cocoa, building things with LEGO -- and also cuddling on the couch and watching movies. We've been showing our son the early Star Wars movies -- the ones which came out when we were kids. Recently that's meant The Empire Strikes Back.

George Lucas is on record as saying that Joseph Campbell's writings about the hero's journey were a major influence on these films. And a quick internet search reveals a lot of essays about the theology implicit in the films, from Star Wars Spirituality in Christianity Today to Monomaniacal in Tablet. What strikes me, watching the movies again now with our son, is how Star Wars makes me think of the germinal work of Jewish mysticism, the Zohar.

We read in the Zohar ממלא כל עלמין וסובב כל עלמין -- "You fill all worlds and surround all worlds." The Zohar also teaches that God clothed the first human beings not in garments of skins, but in garments of light. (The Hebrew word for light אור and the Hebrew word for skin עור are homonyms: they are both pronounced or.) In the world to come, teaches the Zohar, we will wear garments made of light, woven from the mitzvot we performed in this life.

Luminous beings are we. And the Force pervades all worlds. Sounds pretty Zoharic to me.

It turns out I'm not the first person to make that observation either -- Eliezer Segal's The Force is With Us notes a variety of places where Star Wars aligns with kabbalistic teachings: not only the binarism between darkness and light, but also the idea of descending into the darkness in order to defeat it. For that matter, the whole idea of the "Dark Side" is parallel to the kabbalistic idea of the sitra achra, the "other side" to which darkness cleaves.

(I'm ignoring altogether the nonsense about midichlorians which George Lucas inserted into the later films, which turned the Force into something which can be measured in the bloodstream. As far as I'm concerned, that was a retrofitting of the original mythology, and not an interesting one.)

I wonder what our son is taking away from these movies. He probably sees them as an epic battle between good guys and bad guys, which is simplistic but age-appropriate. Someday when he's old enough, I hope he'll be interested in learning some Zohar with me, or with another teacher who speaks to his heart. And maybe when he does, he'll remember these Star Wars movies and smile.

February 6, 2015

Morning. Prayer.

This morning I sat in our sanctuary, put on my tallit and tefillin, and quietly played guitar for a while. This was one of those days when no one showed up for Friday morning meditation -- which was not a surprise to me; the thermometer in my car read -7 when I dropped our son off at preschool -- so I got to spend a quiet 20 minutes there by myself.

This morning I sat in our sanctuary, put on my tallit and tefillin, and quietly played guitar for a while. This was one of those days when no one showed up for Friday morning meditation -- which was not a surprise to me; the thermometer in my car read -7 when I dropped our son off at preschool -- so I got to spend a quiet 20 minutes there by myself.

I played the cowboy Modah Ani, and sang the words into the silence of the room. It always makes me smile, not only because the "moo" is silly but also because it reminds me of the beloved rabbi friends from whom I learned the melody in the first place. I played Rabbi Shefa Gold's Elohai Neshama -- "my God, the soul which You have placed within me is pure..."

I sang some morning blessings. I sang part of a psalm of gratitude. I sang some of the words to the Yotzer Or blessing which praises God Who creates light -- not only the light of the sun and moon and stars, but also the light of wisdom and insight. I sang some of the words to the Ahavah Rabbah blessing which praises God Who loves us with an unending love.

I picked out the chords which accompany weekday nusach, the minor melodic scale which I have learned to use on weekdays for singing the prayers at the heart of our service. I sang the Shema, declaration of the Unity at the heart of all things. I sang words of gratitude for redemption. And then I sat in silence for a while, words and melodies swirling in my mind and heart.

A moment ago I typed "worlds and melodies" instead of "words and melodies." I think both are true. Daily we bless the One Who speaks the world into being -- and our words too contain worlds. Create worlds. Can destroy worlds. All of these whipped around in my mind like the dry sparkling snow forming dust devils on this morning's cold roads. I spoke silently about these things with God.

I have learned to integrate prayers (and prayer, not just the words of our liturgy but the intention) into my mornings -- to cultivate gratitude on waking with Modah Ani, to bless the One Who revives me with the bracha m'chayyei ha-meitim when I sip the day's first coffee or tea. But I'm also always grateful when I get the chance to sink deeper into prayer at the beginning of my day.

On these days surrounding Tu BiShvat I've been thinking of how each human being is like a tree. How I am like a tree. How much I need light. How much I need soil. How prayer is the water which feeds my roots. When I daven, I send rootlets down to find water. When I can draw it up into my whole being, that's when I am able to bring forth the gifts I want to give to the world.

Shabbat shalom, y'all.

February 5, 2015

Snowy Tu BiShvat

I've come to love celebrating Tu BiShvat in the snow. I know that in the Mediterranean, where this festival originates, this time of year means blooming fruit trees. In south Texas, which has a very Mediterranean-like climate, things are beginning to bloom at this season too. (Plenty of things which thrive around the Mediterranean -- oleander, bougainvillea, date palms -- are native flora where I grew up too.) In a climate like that, it makes sense to think of this as a season of new life.

But in New England -- maybe especially in the Berkhire hills which I call home -- this January-February corridor usually means snow. And this year we've got even more of it than usual. On our deck, the snow reaches almost to the tabletop of the glass-topped table, and then tops that table with a two-foot-tall white cap. Our barbecue grill: topped with a two-foot-tall white cap. Even the bird feeder is topped with a comical little cone of snow. The world around me is white on white on white.

This is our deck with table and chairs.

It's fortunate for me that I really like snow. It was so magical and unusual when and where I grew up that even after more than two decades living in the north, I'm still not tired of it. (Sleet and freezing rain, on the other hand, I could do entirely without.) And I've learned, over the years, that a snowy winter often presages a good sugaring season. When the mercury rises above freezing during the day and dips back down at night, those are the conditions which make for good sweet sap.

I love Tu BiShvat because it feels like the first step out of winter and toward spring. Even though everything around me is snow-covered, Tu BiShvat reminds me that there are stirrings of growth deep beneath the surface. The trees will awaken, and in time they'll unfurl leaves. And along with them, what in me is biding its time and preparing to blossom? What would it feel like to truly grow where I'm planted? What sweetness might rise in my heart and my spirit as these winter days unfold?

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers