Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 134

March 4, 2015

Disagreement for the sake of heaven

I had the opportunity to do something really neat last night -- to participate in a livestreamed Torah discussion with two colleagues, organized as part of 9 Adar: the Jewish Day of Constructive Conflict. What's 9 Adar? Glad you asked:

I had the opportunity to do something really neat last night -- to participate in a livestreamed Torah discussion with two colleagues, organized as part of 9 Adar: the Jewish Day of Constructive Conflict. What's 9 Adar? Glad you asked:

The 9 Adar project seeks to strengthen the Jewish culture of constructive conflict and healthy disagreements. In our ancient texts, it is called machloket l’shem shemayim (disagreements for the sake of Heaven). It means arguing the issues while respecting and maintaining good relationships with the other side, making sure that your personal motivation is to come to the best solution and not just to win, admitting when you are wrong, and acknowledging that both sides might be right. Approximately 2,000 years ago on the 9th of Adar, two major ideological schools of thought, Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai, allowed their disagreements to degrade into terrible conflict. Today, we are using the day to promote the original culture of healthy and constructive conflict.

There have been a variety of 9 Adar events in various places over recent days and weeks. (The ninth day of the lunar month of Adar was actually a few days ago; our event happened a few days after the date itself, but was nevertheless part of the same "Jewish Day of Constructive Conflict" initiative.)

The conversation was between me, my fellow Rabbi Without Borders Rabbi Alana Suskin of Americans for Peace Now, and Rabbi Joseph Kolakowski (profiled as The Chareidi Rabbi from Virginia, though he's no longer there; he's now the assistant rabbi at Congregation Beth Sinai in Kauneonga Lake, NY and Crescent Hill Synagogue in Rock Hill, NY), moderated by Lex Rofes and Caroline Morganti of Open Hillel. The question we were given was:

The figure of Korach has fascinated readers of the Torah for millennia. To what extent do you sympathize with his mindset, and with his challenge to authority? To what extent, alternatively, do you feel that his behavior was ill-advised, or even malicious? Most importantly, what lessons can we learn about this story as we explore our relationships to conflict and authority today?

(Korach, you may recall, was the fellow in Torah who rebelled against Moses' authority; he argued that the whole congregation was holy, so why did Moses hold himself above everyone? Moses said okay, fine, let's put this to God and we'll see who God prefers; and the earth swallowed up Korach and his followers.)

We began by going around the virtual room and each of us offering a few thoughts about Korach. Here's more or less what I intended to say in my opening remarks about Korach and his story:

I find that when I'm teaching Korach to my b'nei mitzvah students, they universally take his side. "What's so bad about Korach? He just didn't want all of the power to be in Moses' hands. And who elected Moses leader, anyway?" -- that kind of thing. I know that I have at times felt great empathy with Korach -- and yet I've noticed that over the last 15 years my empathy for Moses has risen and my empathy for Korach has decreased, and maybe that's a function of me becoming a rabbi, or maybe it's a function of me just getting older, I don't know!

For me, the Korach story is a useful illustration of how not to handle conflict in my congregation. If someone becomes angry with me and how I'm doing things, and I respond with my own defensiveness, then I'm setting the stage for some kind of disaster -- the earth might not literally open up and swallow anyone, but there could be hurt feelings, damaged reputations, etc. We have to find a better way of settling our disputes.

For me the critical question is: was Korach actually acting out of a sense that everyone in the community is holy? Or was he jockeying for more power of his own? If it's really about his own ego and self-aggrandizement (e.g. he wanted some of Moshe's power), then it makes more sense that the earth swallowed him up -- because his makhloket (argument) wasn't really l'shem shamayim (for the sake of heaven).

For me that's what this all boils down to: how to keep our disagreements (including those around Israel/Palestine) for the sake of heaven, instead of for the sake of me being right and you being wrong.

"If the argument is based in love and mutual respect for one another, then it's an argument for the sake of heaven," said Rabbi Kolakowski, quoting the Satmar rebbe. "The way to tell if someone's a zealot and is just arguing for the sake of arguing is, how does that person lead their life in general? Does he argue about everything, or is it only when it's something important and for the sake of heaven that he gets excited and speaks up?"

Rabbi Suskin began by noting that she feels strongly ambivalent about Korach. It's hard for us as moderns not to feel some sympathy for the position of "we're all holy here" -- and yet our commentaries on Korach are pretty strongly negative. It's difficult to do with Torah what we want to do with other kinds of stories, and tell the story from the point of view of the "bad guy" and thereby redeem him.

She pointed out that the rabbis suggested that the reason that Korach's argument was not for the sake of heaven was that when he protested that "all of the people are holy," what he was really saying was not that we all have the capacity to be holy, but that in and of ourselves, without doing anything, regardless of what we do, we're holy. She argued that it's not really Jewish to say "I'm holy no matter what I do; no one can judge me." We're part of the community; our behavior impacts those around us.

From there we shifted into talking about what it means for disagreement to be holy -- Rabbi Brad Hirschfield's You Don't Have To Be Wrong For Me To Be Right -- the Talmudic stories of Reish Lakish and of Kamza and Bar Kamza -- the obligation to rebuke, and also the obligation to recognize where people are and to speak to them in a way that they will hear -- finding the partial truth in opinions with which we disagree -- and more! Here's the video of our conversation, which ran for about 65 minutes:

And if you can't see the embedded video, you can go to it on YouTube - 9 Adar Interdenominational Text Study. If this sounds like fun to you, I hope you'll go and watch.

Purim approaches

Purim begins tonight at sundown. I used to not really get the appeal of this holiday, but over the years I've grown fonder of Purim.

Purim begins tonight at sundown. I used to not really get the appeal of this holiday, but over the years I've grown fonder of Purim.

Yes, for kids it's a fun opportunity to dress up and to make noise in the synagogue (drowning out the name of the wicked Haman.) But there's something here for adults, too. Purim comes one month before Pesach; it's a stepping-stone toward the coming spring.

Purim offers us a megillah (scroll) in which God is never explicitly megaleh (revealed). God's explicit presence is nistar (hidden) in this book -- as Esther (whose name shares a root with nistar) hides her Jewishness when she enters the royal palace.

But Esther reveals her Jewishness when her people need her, and God's presence is palpable throughout the story in the twists and turns of providence. Purim is a holiday of hiding and revealing: Vashti refuses to reveal her body; Esther hides until she needs to reveal her identity; God hides in plain sight.

And Purim is a holiday of inversions: Achashverosh exiles Vashti rather than accede to a woman's will -- and then winds up doing what Esther wants. Haman builds a gallows for Mordechai, and winds up swinging on it himself. Haman tells the king what should be done for someone the king wants to honor, and then has to enact that reward for Mordechai instead of himself. Haman orchestrates the massacre of the Jews, and instead the Jews are given the right to defend ourselves.

Purim is an opportunity to play. To turn things upside-down. To be silly. To hear a pulp fiction soap opera chanted or acted-out from the bimah (pulpit) instead of the kinds of material rabbis usually aim to present -- and to find the hidden meaning even in the silliness. And for the Hasidic master known as the Sfat Emet, it's an opportunity to ascend the tree of knowledge until we reach the high vantage point where our limited human notions of "good" and "evil" disappear into the Oneness of God. I can get behind that.

A freilichen Purim -- may your Purim be joyful!

If you like poetry, you might enjoy a pair of Purim poems I wrote a few years back: Hidden and Purim Pantoum.

March 2, 2015

Women in Religion at Williams College

This Thursday evening I'll be participating in a panel discussion featuring female religious leaders, moderated by my friend Reverend Rick Spalding (the head of chaplaincy at Williams College, my alma mater.) The discussion will be at 7pm on March 5 in Thompson Memorial Chapel, the big stone chapel that's right on route 2. Here's how the event is described on the college calendar:

This Thursday evening I'll be participating in a panel discussion featuring female religious leaders, moderated by my friend Reverend Rick Spalding (the head of chaplaincy at Williams College, my alma mater.) The discussion will be at 7pm on March 5 in Thompson Memorial Chapel, the big stone chapel that's right on route 2. Here's how the event is described on the college calendar:

The Williams College Feminist Collective is hosting a panel of female religious leaders to discuss their careers and how gender has played a role in their religious lives and careers. Panelists including Rabbi Rachel Barenblat, Reverend Beth Wieman, and Chaplain Celene Lizzio-Ibrahim.

I'm delighted to take part, for a variety of reasons. During my own time at Williams I was one of the creators of the Williams College Feminist Seder, so it's neat to be invited back by the current feminist students' group. Also, I know Celene Lizzio-Ibrahim from the Retreat for Emerging Jewish and Muslim Religious Leaders, at which both of us were alumna facilitators last year. I'm looking very forward to meeting Rev. Beth Wieman. And it will be fun to talk with them, for a public audience, about our religious vocations and our lives as women and how those things intersect.

If you're in or near northern Berkshire county, join us -- the evening is free and open to the public.

March 1, 2015

A reminder: psalm workshop coming up

The Berkshire Festival of Women Writers begins today. It's a pretty extraordinary month-long festival; there will be an event every day this month showcasing the voices and words of women here in Berkshire county. (In fact there will be 53 events at 33 venues, and most of them are free.) Pretty amazing, especially given that we're in a semi-rural area hours away from the nearest big city.

I'm taking part in two ways, and one of them is teaching a workshop on writing one's own psalms. (I posted about this a few weeks ago.) I'm teaching at 3pm on March 10 at Congregation Beth Israel in North Adams.

Writing Your Own Psalms

The psalms are a deep repository of praise, thanksgiving, grief, and exaltation, an ancient collection of poetry which also functions as prayer. In this class, each of us will become a psalmist. We'll explore what makes a psalm, read psalms both classical and contemporary, talk about the emotional tenor of the psalms and how they work both as poetry and as prayer, warm up our intellectual muscles with generative writing exercises, and enter into a safe space for creativity as we each write our own psalms. After sharing our psalms aloud and sharing our responses to each others' work, we'll close with a psalm of thanksgiving for our time together.

If you'd like to sign up, you can go to the event's Facebook page and indicate there that you are coming. I look forward to seeing some of y'all there!

February 25, 2015

More light

I snapped this photograph out of our bedroom window yesterday morning. The giant mass of ice at the right of the frame is a series of icicles -- some of which are far taller than I am! -- which have begun to merge into a rippling wall of ice since we've had a few slightly warmer days. I love the delicate pink of the icicles washed by the first rays of morning sun. That color only lasts for a moment.

One of my strategies for surviving a long (and this year, both very-cold and very-snowy) winter is trying to find the beauty in the world around me. At this time of year, that might mean admiring the sweep of bare tree branches, or the way those branches are limned with freshly-fallen snow. On clear days, it definitely means admiring the pinks and golds of early morning daylight.

One day recently I picked our son up at preschool to take him to an after-school activity which we hadn't done in a few weeks. "But Mom," he said, "you usually pick me up when it's getting dark!" I explained to him that 4:30 is dark in December and January, but by late February, 4:30 is still daylight. To my great delight, it was still light at 5:30 when his afterschool activity ended, too.

Our son keeps talking about how March will be spring. (I think there is a calendar at his school which features a picture of flowers and green grass, and I keep trying to explain to him that all of this snow is not magically going to disappear on Sunday -- and that it can snow here all the way through March!) But March will feel more like spring, even with the snow. Because in March we get more light.

Next week will bring Purim, which is definitely a sign of spring. And with Purim comes the knowledge that Pesach is only one month away, and that's one of the sweetest signs of spring I know. Someday the snow will melt and the robins will return. For now, I'll keep looking for glimpses of beauty in the wintery world around us, and thanking God for more light -- more light -- more light.

February 24, 2015

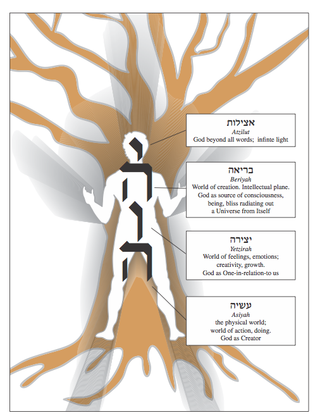

Preparing for a funeral in all four worlds

When I hear news of a death, I feel as though I'm clicking into a higher gear. Life gets faster, details sharper. Everything extraneous falls away. On a practical level (in the world of assiyah) there are so many things which need to be decided: when will the funeral be held? How many nights of shiva does the family wish to observe? Is the obituary drafted, have family members been notified...?

When I hear news of a death, I feel as though I'm clicking into a higher gear. Life gets faster, details sharper. Everything extraneous falls away. On a practical level (in the world of assiyah) there are so many things which need to be decided: when will the funeral be held? How many nights of shiva does the family wish to observe? Is the obituary drafted, have family members been notified...?

On an emotional level (in the world of yetzirah) there's a heightened sense of awareness. It's as though a sense-organ which usually lies dormant has been wakened. How do the family members seem to be feeling? What does this seem to be like for them, what do they need from me, how can I be there for them? And then there's my own emotional landscape: what is this awakening in me? I file that away to be considered at a later time.

Intellectually (in the world of briyah) there's the task of writing the hesped, the eulogy. The goal is to write something meaningful, something which gives a sense for the life which has now ended. The hesped needs to tell stories. It needs to feel real. And it needs to be utterly transparent: this isn't about me as a writer, not about my oratory skills or turns of phrase. It's about the life I'm trying to honor as best I can. My job is to get out of the way.

Spiritually (in the world of atzilut), all of those things intermingle. Death is a doorway into the unknown, a brush with Mystery. I think of it as returning to the Cosmic Source from which we came, like drops of water -- having spent a lifetime falling in slow motion over the waterfall as individual droplets -- rejoining the mighty rush of the river. But it's one thing to say that, and another thing to really face the fact that a life has come to its end, that a soul has gone beyond where we can reach.

The physical world, the emotional world, the intellectual world, the spiritual world. These four worlds are hinted-at, say the kabbalists, in the four letters of God's holiest Name. Those same letters can be mapped on to the human form. Each of us is an expression of that Name. Each of us contains worlds within us. When someone dies, their unique manifestation of those worlds returns to its Source. We are all reflections of that Name; in that sense we are all the same. And we're also all different.

One of my favorite text from Talmud speaks about how God is greater than Caesar. Because when Caesar puts his image, his likeness, on every coin in the realm they all look identical. But when God puts God's image, God's likeness, on every human being we are all different. (Rabbi Arthur Waskow has written beautifully about this: God & Caesar - the Image on the Coin.) We are each a facet of God's image; all alike, because we all contain a holy spark -- and all different, because God is infinite.

When the body's life has ended, the soul returns to the One from Whom it came. From the finitude of a single human body and a single human consciousness, to the infinity of our Source. I believe that there is no suffering on the "other side." I believe that all of our human hurts and fears melt away as we rejoin Infinity. And I know that no matter what I believe about what happens after death, right now my faith isn't as important as my obligation to try to tend to and care for those who grieve.

(Image source: Kol ALEPH.)

February 21, 2015

Praying in the nursing home

When I arrived at the nursing home with my guitar and a pile of prayerbooks, they kindly gave me a bellhop's cart. Better yet, they provided a staff person who could lead me through the labyrinth to the right elevator which would take me to the hallway nearest to the private dining room. In that room there is a china closet with wine glasses inside, and a window with a distant mountain view. Aside from the speaker mounted in the corner, periodically blaring announcements, it feels almost like a home.

When I arrived at the nursing home with my guitar and a pile of prayerbooks, they kindly gave me a bellhop's cart. Better yet, they provided a staff person who could lead me through the labyrinth to the right elevator which would take me to the hallway nearest to the private dining room. In that room there is a china closet with wine glasses inside, and a window with a distant mountain view. Aside from the speaker mounted in the corner, periodically blaring announcements, it feels almost like a home.

We'd never done this before -- bringing the service in to the nursing home. I have one congregant there, and he used to be among our most faithful daveners. We've missed him, the last few years as he's been increasingly unable to come to shul. And then his daughters asked whether we could bring shul to him. So we put the word out, and we hung a sign on the door of the synagogue in case anyone dropped by this morning expecting our usual services, and we met in the nursing home instead.

I had brought ten copies of a handout I had prepared, containing a song and a tiny excerpt from this week's Torah portion. I had brought a pile of fifteen siddurim. At first it seemed as though that would be sufficient, but as more and more people arrived, we pulled extra chairs in from the dining hall next door. Eventually people shared prayerbooks and looked on with each other, which had not been intentional on my part, though I think it actually led to a deeper feeling of connection with each other.

We sang as many old melodies as I could come up with, from "Mah Tovu" to "Adon Olam." The music is a carrier wave for the meaning behind the prayers, and I wanted to reach the patriarch who sat with us, eyes closed, clenching his daughters' hands. We touched on every prayer in the morning service, but did some of them in abbreviated form; what I wanted most was for the rhythms and sounds to gently enter our elder's heart. I chanted a bit of Torah and offered a blessing for everyone present.

After the Torah reading I shared a glimpse of the ideas about which I had planned to speak, about the Torah of wholeness and how each of us is a Torah (stay tuned -- I'll post that tomorrow), and then I offered an impromptu teaching about how our ancestors carried in the ark both the second set of tablets and the shattered first set of tablets. From this we learn to cherish not only our wholeness, but also our brokenness. We are precious not only when vigorous, but also when broken by illness or age.

When it was time for the kiddush afterwards we stood in a circle around the refreshments which our patriarch's daughters had provided. We sang the borei pri hagafen blessing over bunches of grapes because we had gotten our wires crossed about who was bringing juice and wine; we sang the borei minei m'zonot blessing over coffee cake because the same miscommunication had meant there was no challah. It didn't matter. All around the room were smiles, and clasped hands, and open hearts.

I love leading services in the sanctuary at my shul. We have an extraordinarily beautiful space, with tall windows looking out over an amazing panorama of wetlands and mountains and meadow. And yet there's something special about bringing our community and our familiar prayers into a setting like this. As a friend noted to me afterwards, praying in this way helps one to realize that the words and the heart behind them are what connects us -- not the building, no matter how beautiful it may be.

February 20, 2015

Spreading a little bit of hope

The world is full of terrible news, including news about inter-religious mistrust, hatred, and violence. And since it's Adar and we're supposed to be joyful, I thought I'd signal-boost a few hopeful things which have come across my transom recently. First is a small one -- a reminder that there are individuals out there who buck trends of mistrust between different religious communities:

MOROCCO: Lahcen, Berber Muslim from Arazan has kept a promise for 70 years to clean the grave of his Jewish friends. pic.twitter.com/jzbqI31oLx

— Children of Peace (@ChildrenofPeace) February 19, 2015

I found this image beautiful -- the care with which he is tending to the Hebrew-inscribed headstone speaks to me of meaningful relationship. A bit of online digging reveals that there have been Jews in Morocco since Roman times, though today only about 2,500 remain. You can read a bit more about Lahcen and his spiritual generosity here: 8 touching stories of Jewish and Muslim friendship.

Next, here's one which involves a lot more people. You've probably read about the recent shootings outside a Copenhagen synagogue and free speech rally. 30,000 Danes marched peacefully in response to those shootings, and the Prime Minister of Denmark spoke in solidarity with Danish Jews. (Read all about it: 'Attack on Jews is an attack on all of us': Thousands of Danes Rally in Copenhagen.)

Here's another response to the violence in Copenhagen, and to the bigger picture of how members of different minority religious traditions relate to each other in Europe: Muslims plan 'peace ring' around Oslo synagogue. That was the first (brief) article I read about the intention of one Muslim community to make a statement about caring for local Jews. Here's a longer one, from the Washington Post:

The headlines have been grim...But the future of tolerance and multiculturalism in Europe is far from bleak. The bigotry on view has been carried out by a fringe minority, cast all the more in the shade by the huge peace marches and vigils that followed the deadly attacks. And some communities are trying to build solidarity in their home towns and cities...

Ervin Kohn, a leader of Oslo's small Jewish community, had agreed to allowing the event on the condition that more than 30 people show up — a small gathering would make the effort look "counter-productive," Kohn said. Close to 1,000 people have indicated on Facebook that they will attend.

(Read the whole thing: Norwegian Muslims Will Form a Human Shield Around Oslo Synagogue.) Obviously something like forming a "human shield" or "peace ring" is a onetime happening, but to me the fact that so many people are interested in participating says to me that this is a meaningful expression of support which will, God willing, last beyond the day of the peace ring's formation.

On a related note, I've been watching the #IGoToSynagogue hashtag on Twitter. The hashtag began as a Jewish initiative, a way for Jews to proudly assert that despite violence at one of our houses of worship, we will still continue to gather, live, pray, mourn, and celebrate as holy community. Dayenu, that would have been enough. But the hashtag is also being used in an unexpected way.

Here's the image which I'm seeing all over my Twitter and Facebook feeds -- Muslims Ayse Cindilkaya and Bacem Dziri at a synagogue, holding a sign bearing that hashtag and declaring that they stand for the safety and sanctity of all houses of worship, not only their own. The photo bears the logo of the European Muslim Jewish Dialogue group, and it's a lovely show of solidarity with Jews:

1 tweet says it all RT @lezarub #igotosynagogue pic.twitter.com/n17HFtaMOf

— Ben Af Rothenberg (@RisingRedStorm) February 19, 2015

(If the above image doesn't appear, you can go directly to it by clicking on this link.) And last but not least, speaking of solidarity with one another: here's an article in the Times of Israel which I found worth reading -- London's Faithful Walk Together in Show of Solidarity.

[A]s they walked, wide-eyed, into the airy piazza of the mosque, to greet and meet people of all faiths and none, there was a palpable relaxing of shoulders and a cheerful atmosphere.

The mosque was the first stage in a simple but charming initiative, called the Coexist Pilgrimage, devised by faith leaders in response to the attacks in Paris in January. The alumni of the Cambridge Coexist Leadership Program already knew each other. So when a rabbi – Masorti Senior Rabbi Jonathan Wittenberg — and a Christian minister, the Rev Margaret Cave, put their heads together with the assistant secretary-general of the Muslim Council of Britain, Sheikh Ibrahim Mograbi, it wasn’t hard to come up with the idea of the faith walk...

At a moment in time when we're hearing a lot about the awful ways that human beings can treat one another, here are some glimmers of common ground and of hope. Shabbat shalom to all who celebrate.

February 19, 2015

It's Adar! Let's be happy!

Chodesh tov -- happy new month of Adar!

This is the month of which our sages said, "When Adar enters, joy increases." In light of that, here's a setting of the c. 11th century hymn "Adon Olam," which is part of traditional daily prayer and which we sing at my shul every single Shabbat, set to the melody of Pharrell Williams' 2014 hit "Happy."

(Speaking of which -- if you missed Ethan's piece in The Atlantic last year, YouTube Parody as Politics: How The World Made Pharrell Cry, it's worth reading. And there are some amazing international "Happy" videos at We Are Happy From -- the one I remember from Madagascar seems to have been taken down, but there's a lovely one from Namibia...)

Here's to Adar and to being happy!

February 18, 2015

Celebration and change in deep winter

I wonder sometimes how it came to pass that so many cultures have celebrations / carnivals / festivals around this time of year. Christians have Mardi Gras, the "Fat Tuesday" carnival which precedes the Lenten season; Hindus have Holi, the festival of colors celebrated at the full moon nearest to the spring equinox; Jews have Purim, our festival of costumes and disguises and topsy-turviness, also at full moon, also near the spring equinox. Maybe there's something about deep winter which awakens a cross-cultural human yearning for bright colors, merriment, and change.

Giant painted wooden gragger, showing a scene from the Megillah of Esther.

The shortest days of the year are well behind us. (And I am grateful for that. I thrive on longer light.) But just as summer's strongest heat comes well after the longest day of the year, winter's deepest cold comes well after the shortest day. The thermometer in my car this morning registered -5 as I drove our son to preschool. He is fascinated by the fact of negative numbers, and we talk about them often. I'm not sure I knew what negative numbers were when I was his age. Then again, I didn't grow up in a place where negative numbers routinely register on the thermometer as winter unfolds.

By mid-morning the mercury had risen some 25 degrees, and by comparison the air feels -- well, balmy would be an overstatement, but certainly more comfortable! The sun on the snow is so bright that it creates the illusion of warmth; I opened the windows in my car to let in some crisp fresh air. And today is a bright, cloudless, blue-sky day. Sunshine sparkles on the dry dunes of snow. But even with the sun, this is a time of year when winter seems to be lingering. February may be the shortest month on the Gregorian calendar, but experientially, it can drag longer than any of the others.

Intellectually I know that winter will end. But the deep freeze feels as though it couldn't possibly budge. Like one of the doors of our house which keeps freezing shut -- it feels as though winter has frozen into place and will never melt. This is exactly when I need Purim most: the raucous cry of the graggers drowning out the name of wicked Haman, the over-the-top soap opera qualities of the Megillah of Esther, the costumes, the nip of celebratory schnapps. Purim comes to remind us that things aren't always what they seem and that God -- while sometimes hidden -- is always present.

One of Purim's themes is change. The wicked vizier winds up hoisted by his own petard; the hidden heroine shows her true colors; the Jews who were going to be victims of a massacre emerge victorious. (Okay, actually the violence at the end of the story is problematic for me, but that's another post.) If those things can change, surely something as simple as the season will change too, in the fullness of time. One of the names by which we know God is Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh, "I am becoming Who I am becoming." God is always-becoming, never-standing-still. We find God in the simple fact of change.

It's easy to slide into late-winter doldrums. And for those of us who live in snowy climes like this one, this is a time of year when the eye craves color. Everything around us is white and grey and brown, snow and slush and dirt. My bright purple coat and red hat feel necessary, as though their bright colors were actually nourishing. (They may not nourish my body, but surely they nourish my soul.) This is exactly when we need something to shake us up and remind us that there's more to life than slush and road salt. Enter these late-winter festivals, the first early harbingers of the coming spring.

In case you were wondering: Mardi Gras was yesterday; Purim will be two weeks from tonight; Holi will be two weeks from Friday.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers