Marc Lesser's Blog, page 7

April 18, 2024

The Practice of Effort and Effortlessness

In this issue:

· Insights Into Practices

· A Poem, by Naomi Shihab Nye

· Half Day Retreat

· Weekend Retreat

The Practice of Effort and Effortlessness

One of my favorite stories about effort and effortlessness is about a martial arts student who asks his teacher,

“How long will it take for me to become a black belt?”

The teacher responds, “Ten years.”

The student looks puzzled and impatient and says,

I’ll work harder and push myself to excel. I’ll be the best student. How long will it take in that case?”

The teacher pauses to consider this additional information, smiles, looks at his student and says,

“In that case, it will take 20 years.”

Aldous Huxley referred to this as the “Law of Reversed Effort” expressing that when we overly exert ourselves or try too hard to achieve a particular outcome, we may actually impede our progress.

Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki addresses this issue by saying “The most important point in our practice is to have right or perfect effort.”

He goes on to say:

“If your effort is headed in the wrong direction, especially if you are not aware of this, it is deluded effort. Our effort in our practice should be directed from achievement to non-achievement.”

Usually when you do something, you want to achieve something, you are attached to some result. Moving from achievement to non-achievement means releasing any sense of attachment and getting rid of unnecessary and bad results of effort.

When you make some special effort to achieve something, some excessive quality, some extra element is involved in it. You should get rid of extra or excessive things.

People ask what it means to practice meditation with no gaining idea, what kind of effort is necessary. The answer is: “effort to get rid of something extra.”

Practice:

For most of us, engaging with effort and effortlessness is an enormous challenge. We live in a world where accomplishment, and getting things done is essential. How paradoxical that more, or extra effort might not lead to the results we aim for.

I’ve noticed in my executive coaching practice that most leaders think they need to be really hard on themselves in order to get anything done. The experiment I suggest is to try being more kind and accepting of yourself and see how that impacts your productivity. I’ve rarely been disappointed with the outcome of this experiment: insights arise in how more awareness and kindness lead to both greater productivity and enjoyment.

As Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki describes, the practice is to bring more awareness to the way you exert effort — are you doing anything extra?

Experiment with appreciating and enjoying the process, explore a bit more kindness and appreciation of yourself and the process. See what happens.

Explore envisioning an outcome without worry, without fear, with less extra effort.

A Poem

Famous, Naomi Shihab Nye

The river is famous to the fish.

The loud voice is famous to silence,

which knew it would inherit the earth

before anybody said so.

The cat sleeping on the fence is famous to the birds

watching him from the birdhouse.

The tear is famous, briefly, to the cheek.

The idea you carry close to your bosom

is famous to your bosom.

The boot is famous to the earth,

more famous than the dress shoe,

which is famous only to floors.

The bent photograph is famous to the one who carries it

and not at all famous to the one who is pictured.

I want to be famous to shuffling men

who smile while crossing streets,

sticky children in grocery lines,

famous as the one who smiled back.

I want to be famous in the way a pulley is famous,

or a buttonhole, not because it did anything spectacular,

but because it never forgot what it could do.

Half Day Sitting, In-Person and Online

Sunday, May 26th, 9:00 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. in Mill Valley.

I really like half day retreats, where there is time for some extended meditation periods, some walking, and time to process with a small community. Then, time to enjoy a Sunday afternoon.

Weekend Retreat at Green Gulch Farm

November 1 – 3

In our world of busyness, of more, faster, better, this retreat offers time to stop, reflect, and renew – a time to step fully into the richness of your life. Together we’ll follow a gentle schedule of sitting and walking meditation, interspersed with talks and discussions from the wisdom of Zen teaching as we explore how these stories and dialogues may be utilized in our relationships, our work, and our lives.

This retreat is open to all people interested in stopping, exploring, and bringing more awareness and mindfulness to daily life.

The post The Practice of Effort and Effortlessness appeared first on Marc Lesser.

April 11, 2024

The Problem: Ignoring Problems

In this issue:

· Insights Into Practices

· Kaizan

· A Poem

· Weekend Workshop at Green Gulch Farm, November 1 – 3

“Don’t stop the line.” For many years this was an agreement, almost an unwritten law of the General Motors assembly lines building cars and trucks. Management believed that keeping the car assembly line going at all times was essential. According to a 30-year GM employee, management assumed that “If the line stopped workers would play cards or goof off.” As a result of this philosophy and way of working, problems were ignored instead of addressed. Defective cars, some missing parts, or cars with parts put on backwards were put into their own special “defective” lot. This lot grew to enormous proportions. Addressing and fixing these problem cars became too costly.

In late 2008, a group of General Motors assembly workers were sent to Fremont, California, as part of a GM/Toyota collaboration called NUMMI. Several GM managers were flown to Japan to learn Kaizan, the Japanese methodology for building cars. What they discovered— was an amazing aha! Anyone on the assembly line who had a concern about the quality of a part could stop the line at any time. Problems were addressed immediately. Groups of workers got together and solved problems. Toyota managers assumed that their workers wanted to build the best cars possible, and though facing problems immediately might have short term negative consequences, it would have enormous long-term benefits. Toyota consistently built better quality cars with more efficiency and lower costs.

General Motors resisted change, went into bankruptcy, and needed to be bailed out in 2008 by American taxpayers for many reasons. There were so many problems facing the company, but one notable contribution to its downfall was producing a poor quality product caused in part by not stopping and solving problems.

It is easy to look at GM and see their folly, and this particular GM tale is a well-known story in today’s organizational effectiveness lore. But what about my company and my life, and your company or your life?

When do we not face “small” problems and put them off till later?

In my coaching and consulting practice, I notice many versions of “don’t stop the line.” It might take the form of:

Don’t question the boss.

We’ve always done it this way.

Don’t confront the rude star salesperson.

We are just too busy right now!

There are many subtle and not so subtle behaviors and habits of overlooking and avoiding problems in the world of work (and outside of work.) Stopping, admitting mistakes, working collaboratively and improving processes that are for the good of the organization, require courage, and the willingness to stop, pause, and ask difficult questions.

Some questions:

What version of “don’t stop the line” is embedded in your organization, relationships, and your life?

What might stopping look like?

How might your work and life benefit from stopping and pausing? What are the risks? What might the rewards be?

Kaizan

Here are some of the core steps from the Kaizan approach:

1. Identify the problem. Start small.

2. Learn from mistakes:

Figure out what went wrong, learn, and move on.

3. Celebrate small wins:

The small things add up.

4. Value feedback:

Listen to what others say.

Their insights can help you improve.

5. Get others involved:

Teamwork is important and valuable.

7. Reflect on your progress:

Take time to look back at your improvements.

Then, set new goals.

8. Repeat, with patience and possibility:

There’s almost always room for improvement.

Keep looking for ways to learn, grow, and to find solutions.

A Poem

Our Story, by William Stafford

Remind me again—together we

trace our strange journey, find

each other, come on laughing.

Some time we’ll cross where life

ends. We’ll both look back

as far as forever, that first day.

I’ll touch you—a new world then.

Stars will move a different way.

We’ll both end. We’ll both begin.

Remind me again.

Step Into Your Life: A Zen Inspired Retreat

November 1 – 3

Green Gulch Farm

In our world of busyness, of more, faster, better, this retreat offers time to stop, reflect, and renew – a time to step fully into the richness of your life. Together we’ll follow a gentle schedule of sitting and walking meditation, interspersed with talks and discussions from the wisdom of Zen teaching as we explore how these stories and dialogues may be utilized in our relationships, our work, and our lives.

We will practice with the essence of meditation, just sitting with what is. And we will experience a variety of guided meditations, exploring our inner voices, our intuition, and our emotions. Through meditations, conversations, awareness practices, and writing we’ll create a safe, vital, and meaningful time of learning together. This retreat is open to all people interested in stopping, exploring, and bringing more awareness and mindfulness to daily life.

The post The Problem: Ignoring Problems appeared first on Marc Lesser.

April 4, 2024

Thinking And Doing Impossible Things

In this issue:

· Insights Into Practices

· A Poem, Maybe You Are King?

· One Half-day Retreat

· Books For Doing Impossible Things

Insights Into Practices: Thinking And Doing Impossible Things

I often think about the time I arrived at an improv for beginner’s class and the teacher announced, “Today we are going to be doing improvised Shakespeare.”

My heart sank. My stomach clenched. I wanted to bolt. I quickly and nervously approached the teacher and said, “I never really studied much Shakespeare…”

Immediately, before I could express my doubts and concerns she looked at me with a big grin and excitedly responded, “Great!”

It turned out to be a lot of fun and lots of learning, right within the discomfort, fear, and thinking “impossible!”

The reason I took improv classes was to face my fears, especially my fears around public speaking. At that time, I couldn’t imagine being in front of a group without a fully written script of what I would be saying. I used to make several copies, for back-ups and put them in several of my pockets, just in case.

It makes me smile to look back at things I used to think were impossible. I now appreciate teaching and public speaking. Working with groups of leaders and with companies is one of my favorite things in the world to do. I savor being able to help create a safe space and engage in ways to integrate work, leadership, and mindfulness practices. And, I still feel nervous, sometimes fear, and usually some discomfort.

These days I think that doing the things we might label as impossible may be important, perhaps essential, for our own well being and in making a positive difference:

· Living a fully integrated life where your work, family, friends, and spiritual practice are healthy and seamless. This often feels impossible and aspirational. Especially when children are involved, transitions, unsatisfying work, health challenges, and on and on…

· Building a caring, and effective work culture. Cynicism is easy. Struggle and disconnect at work are easy. Building a culture that is loving and vibrant often seems impossible.

· Starting or being part of a meaningful and successful business: taking an idea and making it useful, serving others, and effective. Is this really possible?

· Keeping your heart open while the world is at war, while our politics is insane and depressing, and there are unspeakable divisions and violence. Impossible, and yet…what is the alternative?

· How do we practice and live our daily lives, knowing that we will say goodbye to everyone and everything we love? Impossible. And yet…

My daily meditation practice these days feels like an exercise in doing the impossible and becoming more comfortable with discomfort — aspiring to let go of my usual judgments, and instead focusing on being curious, kind, and loving. My mind continues to spin and the various voices in me rarely fall silent. And yet, this feels like an important practice for me, staying with it, every morning, in supporting all of my daily impossible tasks.

(Playing with a wild bear in Mill Valley, California.)

I’ve come to believe that we are impossible beings who live in impossible times.

I believe it is important to train ourselves to enter challenges and difficulties that help us to act, to try things, to keep our hearts open, even and especially when it looks challenging, difficult, or impossible.

A Poem: Maybe You Are King?

This poem called A Story That Could Be True, by William Stafford, poses these questions: “Who are you really, wanderer?” and a possible response “Maybe I’m A King?”

If you were exchanged in the cradle and

your real mother died

without ever telling the story

then no one knows your name,

and somewhere in the world

your father is lost and needs you

but you are far away.

He can never find

how true you are, how ready.

When the great wind comes

and the robberies of the rain

you stand on the corner shivering.

The people who go by—

you wonder at their calm.

They miss the whisper that runs

any day in your mind,

“Who are you really, wanderer?”—

and the answer you have to give

no matter how dark and cold

the world around you is:

“Maybe I’m a king.”

Half Day Retreat, In-person and Online, Sunday April 7th

9:00 a.m. – 12:30 p.m., in Mill Valley, CA

In our world of busyness, of more/faster/better, this half-day retreat offers time to stop, reflect, and renew. We will explore the practices of effort and effortless as a path to well-being and “stepping into your life.”

Together we’ll follow a gentle schedule of sitting and walking meditation, a talk, and some discussion. Anyone looking to begin or deepen a meditation and mindfulness practice is invited to attend.

What is meditation? I like a definition proposed by Zen teacher Dogen, the 13th century founder of Zen in Japan: “The practice I speak of is not meditation. It is simply the dharma gate of repose and bliss…It is the manifestation of ultimate reality…Once its heart is grasped, you are like a dragon when he gains the water, like a tiger when she enters the mountains.”

Some Books About Doing Impossible Things

The Wright Brothers, by David McCullough. Orville and Wilbur Wright set off on a mission to find a way for humans to fly. Impossible!

Zen And the Art of Saving The Planet, by Thich Nhat Hanh. Zen, reversing climate change? Really?

Zen Mind Beginner’s Mind, by Shunryu Suzuki. Transform yourself into a spiritual, trustworthy, and effective person. Who would ever take this on?

The Art of The Impossible, by Steven Kotler. The title says it all…

Love In The Time of Cholera, by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Beautiful novel of love and extreme, impossible challenges.

The post Thinking And Doing Impossible Things appeared first on Marc Lesser.

March 28, 2024

Belonging. So Much To Admire and Weep Over. Don’t Wait.

In this issue:

· Insights Into Practices: Belonging

· My Favorite Fact This Week: The Bar-Tailed Godwit

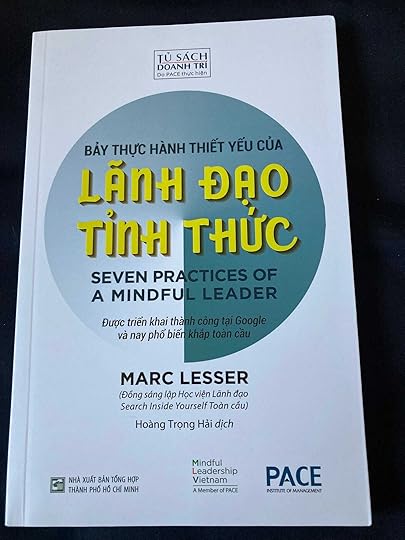

· Seven Practices Of A Mindful Leader, In Vietnamese

· One Half-day Retreat

Insights Into Practices: So Much To Admire and Weep Over.

It’s been a full, rich, and intense week. I’m grieving over the unexpected death of a young woman friend; a hiking accident. At the same time, I’m grieving and celebrating the loss of another close friend who died in London several months ago. On Sunday I helped hold space for family and friends in Los Angeles to celebrate her life.

I gave the Saturday morning public talk at the San Francisco Zen Center this week and began by reading this poem, by Mary Oliver, called The Fourth Sign of the Zodiac. See if you can slow down enough to take it in, hear each word, each line, as though it were an offering or a gift, a gift to support your wellbeing:

“I know, you never intended to be in this world.

But you’re in it all the same.

So why not get started immediately.

I mean, belonging to it.

There is so much to admire, to weep over.

And to write music or poems about.

Bless the feet that take you to and fro.

Bless the eyes and the listening ears.

Bless the tongue, the marvel of taste.

Bless touching.

You could live a hundred years, it’s happened.

Or not.

I am speaking from the fortunate platform of many years,

none of which, I think, I ever wasted.

Do you need a prod?

Do you need a little darkness to get you going?

Let me be as urgent as a knife, then, and remind you of Keats,

so single of purpose and thinking, for a while,

he had a lifetime.”

(I had to look up the reference to Keats: He died of tuberculosis at age 25. When he was 8, his father fell of a horse and died. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was 14 and he lived with his grandmother.)

Three themes in this poem stand out to me:

Belonging – Feeling alone and separate are easy. Belonging, is our innate place and gift. Belonging seems to require practice, awareness, and taking time.

I’ve been reading Thich Nhat Hanh’s Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, and appreciate his words about belonging and love:

“If we look with the eyes of non-duality, we can establish a very close relationship between our heart and the heart of the Earth. When we can see that our beautiful Earth is not inert matter but a living being, right away something is born in us; some kind of connection, a kind of love. We admire, we love the Earth and we want to be connected.

That is the meaning of love, to be one with. And when you love someone, you want to say I need you. I take refuge in you. It’s a kind of prayer, yet it’s not superstition.”

This feels like belonging.

So Much To Admire and Weep Over – Admiring and blessing everything, is so obvious, and yet, easy to forget or not pay attention to. And weeping, more and more feels like a very close cousin of admiring and blessing.

Don’t Wait – “You could live a hundred years, or not.” There is something about this contrast, and the power of the words “or not.”

Practice

· Take time to be with this poem, to explore belonging, letting go of not belonging. Try on as Thich Nhat Hanh suggests, “look with the eyes of non-duality” beyond belonging or not belonging.

· Practice appreciating this life. Take time. Take even more time. Relax, chill, see what happens without extra effort.

· Be wary of putting things off. What matters today, now?

My Favorite Fact This Week

I was reading that brains of birds have a lot in common with human brains. And, that there are some things they can do that our human brains are incapable of. For example, I read in this week’s NY Times Science Section that bar-tailed godwit flies 7,000 miles from Alaska to New Zealand in eight days of continues flight. During this time, one hemisphere of its brain can sleep while the other hemisphere is awake. Perhaps someday we humans will evolve to perform this feat!

And, 7,000 miles of flight. Wow!

Seven Practices of a Mindful Leader: Lessons From Google and a Zen Monastery Kitchen , in Vietnamese

I just received this copy of Seven Practices, translated to Vietnamese. Something magical about books, helps me appreciate the art and privilege of writing and publishing, and how books can spread and influence, in very unexpected places.

And, my books, in English can be found here.

Half Day Retreat, In-person and Online, Sunday April 7th

9:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m., in Mill Valley, CA

In our world of busyness, of more/faster/better, this half-day retreat offers time to stop, reflect, and renew. We will explore the practices of effort and effortless as a path to well-being and “stepping into your life.”

Together we’ll follow a gentle schedule of sitting and walking meditation, a talk, and some discussion. Anyone looking to begin or deepen a meditation and mindfulness practice is invited to attend.

What is meditation? I like a definition proposed by Zen teacher Dogen, the 13th century founder of Zen in Japan: “The practice I speak of is not meditation. It is simply the dharma gate of repose and bliss…It is the manifestation of ultimate reality…Once its heart is grasped, you are like a dragon when he gains the water, like a tiger when she enters the mountains.”

The post Belonging. So Much To Admire and Weep Over. Don’t Wait. appeared first on Marc Lesser.

March 21, 2024

The Art and Practice of Mindful Communication

In this issue:

· Insights Into Practices: High standards and flexibility

· Non-violent communication

· A Poem: Why I Am Happy, by William Stafford

· Half-day Retreat: In-person and online

Insights Into Practices: Not Avoiding and Not Over-reacting

I love how in my executive coaching practice I often learn and grow from the richness of the conversations I’m having with my clients. Recently a CEO asked me how to most skillfully work with one of his leaders who he described as an important part of his team. He told me that this person has very high standards, is detail oriented, and has high expectations of others. These were all positive attributes that the CEO wanted to support.

At the same time, this CEO was aware that this leader sometimes lacked flexibility. Those who worked with him often felt criticized and at times unfairly judged and not supported.

What to do?

We want the people we work with to have high standards. It’s useful to recognize that the shadow side of high standards can be being overly critical and demanding of others.

We also want flexibility and a sense of understanding from those we work with. We want leaders who value empathy and are curious about other’s experiences. It’s useful to acknowledge that the shadow side of flexibility and empathy can be a lack of holding to high standards and a lowering of striving for excellence.

I asked the CEO I was coaching how it might go if he were to have a direct conversation with this leader that might go something like:

“I really appreciate your efforts, and all you do for the company. I appreciate that you hold yourself and others to high standards, standards of excellence. That’s a quality I value and want from everyone in the company.

At the same time, I’ve observed, and hear from some of the people who work with you, that you can at times be experienced as harsh and demanding.

Without giving up your high standards, I need to you be more aware and more flexible. This means practicing perspective-taking; being aware of how your words and actions impact others, and to be interested in how you can skillfully coach and mentors those who work with you.

Is this something you are aware of? Have you received this feedback in this role, or in previous roles, or in other parts of your life?”

I noticed that the CEO was taking lots of notes as we spoke. I too was taking notes – noticing how important and how challenging it can be to not avoid or suppress my feelings and at the same time to not get caught, to get emotionally charged, and over-react.

He said this felt like a really important conversation to have. And, that there were many important conversations within his organization, (and in his life) that needed to take place.

We spoke about this being one of the great challenges and opportunities of leadership. As a leader it’s important to be aware and tuned in to how people around you are communicating, and to be aware of your own feelings and emotions. Then, to not avoid or suppress and not over-react. The practice and aspiration is to have healthy and effective conversations.

Practice:

Where do you fall on the spectrum of holding yourself and others to high standards and at the same time, flexibility and understanding?

Do you tend to under-react or to over-react? How can you train yourself to be more aware, curious, and skillful?

What is your leadership edge? What do you need to develop more of?

Non-violent Communication

After re-reading what I wrote above, I couldn’t help notice that my suggestion was very much aligned with the Non-violent Communication model as originally developed by Marshall Rosenberg.

The four parts of this model are:

Observe – state what you have seen or heard

Feelings – name your feelings, as best as you can

Needs – state your needs

Requests – make a clear request

I followed this model fairly closely in the coaching example.

· I’ve observed that you are a valuable team member and can be experienced as harsh at times.

· I feel concerned about how you are communicating.

· I need you to be more aware of how you influence others.

· I request that you explore being more empathic and understanding.

One of my favorite books on the topic of non-violent communication is Being Genuine, by Thomas d’Ansembourg

A Poem

Why I Am Happy, by William Stafford

Now has come, an easy time. I let it

roll. There is a lake somewhere

so blue and far nobody owns it.

A wind comes by and a willow listens

gracefully.

I hear all this, every summer. I laugh

and cry for every turn of the world,

its terribly cold, innocent spin.

That lake stays blue and free; it goes

on and on.

And I know where it is.

Half Day Meditation Retreat, Sunday, April 7th

Mill Valley and Online

9:30 a.m. – 12:30 a.m.

In our world of busyness, of more/faster/better, this half-day retreat offers time to stop, reflect, and renew. We will explore the practices of effort and effortless as a path to well-being.

Together we’ll follow a gentle schedule of sitting and walking meditation, a talk, and some discussion. Anyone looking to begin or deepen a meditation and mindfulness practice is invited to attend.

What is meditation? I like a definition proposed by Zen teacher Dogen, the 13th century founder of Zen in Japan: “The practice I speak of is not meditation. It is simply the dharma gate of repose and bliss…It is the manifestation of ultimate reality…Once its heart is grasped, you are like a dragon when he gains the water, like a tiger when she enters the mountains.”

The post The Art and Practice of Mindful Communication appeared first on Marc Lesser.

November 30, 2023

We Are All Poets

We begin today’s episode with a short guided meditation focused on being present, fully here with nothing to accomplish. I give a short talk on embracing the mind of the poet and the mind of the business person, exploring these distinctions and lack of distinctions and how we can live and work and play with more meaning and connection.

And today’s Zen Puzzler comes from a traditional koan about a buffalo jumping through a window. The aim of this puzzler is about letting go of our predicting minds and instead seeing the world as fresh and mysterious.

Listen on:

Apple Podcasts

Apple Podcasts  Google Podcasts

Google Podcasts  Podbean App

Podbean App  Spotify

Spotify  Amazom Music

Amazom Music  iHeartRadio

iHeartRadio  Podchaser

Podchaser EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

[music]

Marc Lesser: Welcome to Zen Bones. This is Marc Lesser. Zen Bones is a bi-weekly podcast featuring conversations with leading teachers and activists and an exploration of Zen teachings and practices. Please support our work by making a donation at marclesser.net/donate. We begin today’s episode with a short guided meditation focused on being present here with nothing to accomplish and then do a short talk on embracing the mind of the poet and the mind of the business person. Exploring these distinctions and lack of distinctions in how we live and work and play.

Today’s Zen puzzler comes from a traditional koan about a buffalo jumping through a window. The aim of this puzzler is about letting go of our predicting minds and instead seeing the world as fresh. Seeing through the world of possibility. I hope you enjoy today’s episode. Now let’s begin with a few minutes of sitting practice together.

[bell ringing]

[bell ringing]

[bell ringing]

Marc: Dropping in as much as possible. Dropping into this place where there’s nothing to accomplish. Nothing that needs to be changed or improved. Bringing attention to the body. Finding a way to sit where you can be relaxed, comfortable, and alert at the same time. Noticing the whole body. Relaxing the muscles in the face, relaxing the jaw, shoulders, back, legs, feet. These amazing bodies that we take for granted, usually until something hurts or goes wrong. If there’s anything hurting, giving that some attention. I’ve been paying particular attention to my right foot. I’m giving it some attention right now and loosening the muscles in the bottom of my foot.

Wherever, whatever needs attention for you. Noticing the breath, bringing attention to the breath. Simply allowing the breath to be full and fluid. Breathing in. I know that I’m breathing in. Breathing out. I’m aware. I know that I’m breathing out. It’s one of the earliest teachings of the historical Buddha as the path toward freedom is awareness of the breath. Noticing any, what your approach is. What feelings or mood you’re bringing to this time right now. Whatever that might be, inserting some sense of warm-hearted curiosity. Warm-hearted curiosity. What is it like to be here? What is it like to be alive right now? Let it all go, to let it go. Fading away, right? Fading, let it fade away. No forcing necessary. Keeping it simple. Keeping it simple. Coming back to the breath. Back to the body. Here. Now. Alive. I’m going to ring the bell. Please feel free to continue sitting for as long as you would like to.

[music]

Marc: Finding your inner poet and your inner business person. Finding or embracing. Embracing your inner poet and inner business person. This is what I want to talk about today. I think regardless of our work roles or our usual identities, I think we can all benefit and find greater clarity, meaning, satisfaction in embracing our inner poet as well as our inner business person. I don’t usually think of myself as a poet since I don’t write much poetry. I do love poetry. I do associate as feeling like I’m a business person in a strange way. I think when I was a young person in college, I would not have associated with business people.

There was a certain resistance that I had. I think I had no experience with the world of business, just had some idea. I noticed today, especially it’s interesting, I joke that my Zen friends, my Zen community thinks of me as a business person. I think my business friends, the people in the business community think of me as a Zen student or Zen teacher. It’s interesting just to be curious about these identities for ourselves or for others. What is it that what resistance do we have? Do you have about thinking about poetry or thinking about business?

I think poets and business people there’s our artistic minds and our getting stuff done minds. I think both the mind of the poet and the mind of business people can be quite creative. Through the perspective of poets, our lives I think are mysterious and sacred. I felt this the other day holding a young a newborn baby in my hands, my grandson who miraculously came out of my daughter’s body.

I’ve also recently accompanied a good friend through the dying process. I was in London recently with a good old friend helping her and it’s funny I think she thought I was helping but really she was helping me. She was opening my perspective and body to courageously facing death. Saying hello and goodbye at the same time. This feeling that we are always immersed in again this

holding my newly-born grandson and being with someone as she was dying. For me, at the same time, I’m training leaders in how to listen more attentively, to be more effective. I find the mind of the businessperson is making decisions, leadership presence, and having difficult conversations. As a businessperson, there’s the mind of needing to be responsive, to keep our calendar straight, to be tracking finances, and to be tracking people. Interesting, I think, the mind of a poet and the mind of a businessperson. Maybe they probably overlap in many places, but one is about finding more clarity, right? I think clarity. I’ve been thinking a lot about this topic because I have a fairly new book out called Finding Clarity. One of the things that I write about is, in this book, I say, to me, clarity begins with acknowledging and embodying that the world is not always what it seems. A tree on one level is just a tree. A tree can be dissected and explained in biological terms, yet, when looked at from the perspective of larger reality, a tree is a complete mystery.

We don’t really know what it is or how it got here. The same is true of everything, including us. We humans here on earth, birth, life, death, blood, hearts and hands, stone and sky, consciousness, all are mysteries, sacred mysteries to behold with wonder and awe. Clarity means seeing the world from both perspectives, the ordinary and the everyday, where a tree is just a tree, and the mysterious, which means acknowledging the unknown source of reality.

Clarity is the larger reality. It means seeing beyond or outside of these dualistic, relative ways of perception. On this level, clarity dissolves distinctions. It’s interesting, right? The distinction of the mind of a poet and the distinction of the mind of a business person, and I think we both need to live in a distinct dualistic world. How interesting to let these distinctions dissolve. It makes me think of a conversation that I had with my friend, the poet, Jane Hirshfield. She was talking about surprise, and to me, again, one of my favorite topics, and I think one of Jane’s favorite topics.

In our conversation, she said, everything is surprising to me. Surprise is the great unrecognized emotion of our life, or neurochemistry of our life, perhaps. That surprise is what throws open the brain’s portals to recognize something new and changed. I’ve become more and more interested in this moment of permeability and vulnerability that surprise offers. A long time ago, a study was done, which has stayed with my mind, where neuroscientists were first beginning to study meditation, and they would put people into fMRI machines and monitor their brains. Normal people, if you ring a bell repeatedly every 50 seconds, eventually the attention extinguishes itself, and the sound of the bell no longer evokes any big response in the brainwaves. When they put experienced meditators in the same situation, every ring of the bell evoked a fresh and complete response. It was always new. This was something that Jane had to say.

A part of me likes to transform or question these ideas into practice. How can we practice with the duality, the distinctions between being the mind of a poet, mind of a business person? How do we work with these, and how do we work with the mysteries? One way to practice is to experiment with the mind of a poet, maybe through journal writing. You might explore the prompts, what surprises me about my life right now? Or I’m a poet, when? Or love is, love is. You might read a little poetry every day, even for a minute or two, the poetry of Jane Hirshfield, or Rumi, or Hafez, or Mary Oliver, David White, Naomi Shihab Nye, William Stafford, or you may have your favorite poems.

Reading poems and just seeing what happens, seeing what happens with poetry. I think it’s worth also stepping in fully to the mind of a business person, maybe reading or listening to podcasts of business people. People like Adam Grant, the book Think Again. Maybe the book Dare to Lead by Brene Brown, Atomic Habits by James Clear. Yes, so interesting, I think, and useful, right? We’re all poets, we are all poets, we live in the world, the mystery of our birth and lives and death. We’re all business people. We all need to get stuff done. I want to just read a short poem by Jane Hirshfield, a poem is called Optimism.

More and more I have come to admire resilience.

Not the simple resistance of a pillow,

whose foam returns over and over to the same shape,

but the sinuous tenacity of a tree, finding the light newly blocked on one side, it turns in another.

A blind intelligence, true.

But out of such persistence arose turtles, rivers, mitochondria, figs, all this resinous, untractable earth.

More and more, I have come to admire resilience.

Not the simple resistance of a pillow,

whose foam returns over and over to the same shape,

but the sinuous tenacity of a tree, finding the light newly blocked on one side, it turns in another.

A blind intelligence, true.

But out of such persistence arose turtles, rivers, mitochondria, figs, all this resinous, unretractable earth.

I would add, out of this resilience, resistance, we humans, our consciousness, our bodies, and minds and consciousness arose. Please do explore the mind of poetry and the mind of being an effective, successful, resilient business person.

[music]

Marc: Welcome to the Zen Bones Puzzler, where I will regularly be presenting a story or a Zen koan or a poem, something to contemplate, to think about, a story that has purpose. It’s about developing greater insight and reflection. Not so much for a solution, but as a way to support your practice, a meditation in daily life.

Today’s Zen puzzler, I’m going to return to one of my favorite Zen koans. It’s actually a very traditional Zen koan, which is this image. I’m sure I’ve talked about this before, but it’s a little bit like what Jane was saying about meditation students, is that everything is new and everything is fresh. These Zen stories are meant to come back to and see how it’s the same words, the same image, but how it’s now making it fresh and new, making everything in our lives fresh and new, because it is fresh and new. We don’t have to make it. It’s dropping the predictive nature of our brains, which can– and we want things to be safe. Now this story, what I love about this story is a traditional Zen story about a buffalo that is going through a window. In this Zen story, this Zen koan, it describes how a buffalo jumps through the window and the head and the body and the arms and the legs, everything passes through the window. Everything except for the tail, the tail does not go through the window. This is the story. This is the very traditional Zen koan from the Blue Cliff Record. I think, to me, it’s about the impossibility of our lives a little bit like the traditional Zen vows, right? Beings are numberless. I vow to save them. Delusions are inexhaustible. I vow to end them or I vow to transform them.

Again, these are so core to Zen practice. I think to human practice of embracing, stepping into what is aspirational, mysterious, and impossible. One of the books I’ve been reading, and it’s a book called Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake. It’s a book about seeing the world through the lens of mycelium, through the lens of mushrooms and seeing what happens when we are less human-centric and more the mysterious network of mycelium that we walk on and that in some ways is within or has helped the bacteria with the millions and trillions of bacteria that live inside of us and that support our bodies and minds.

I think this koan, right, the buffalo jumping through the window is don’t be so sure, don’t be so sure of anything, certainly of not labeling yourself as a failure or a success or as a poet or as a business person. See what happens when we let go of the predicting brain and allow every moment to be fresh and new and mysterious. Yes. Whether it’s holding a baby in your arms or being with someone who’s dying or simply noticing a tree. Like, wow, how did that happen? How did that happen? I think this is the feeling that this Zen story brings up. I was thinking of, I did a week-long retreat several years ago where the whole topic was inanimate objects preach the Dharma.

It was an essay by the 13th-century Zen teacher Dogen and really it was again the same topic about not being so sure of things. At the very end of this seven-day retreat, I asked, I asked the last question. This was Shohaku Okamura was the teacher, a wonderful Zen teacher who is Japanese, has been leading a Zen group in Bloomington, Indiana. I asked the last question, which is, we just spent a week on this topic of inanimate objects preach the Dharma. What should I tell my brother who happens to be an electrical engineer in New Jersey? What will I tell him that we did? How did we spend this week of our time? Without hesitating, Shohaku said, you can tell your brother, the world is not what it seems.

The world is not what it seems. I think this is really the message of this koan of the buffalo jumping through the window, leaping through the window. Everything passes except the tail. That darn tail. Something to reflect on. What is it about our predictive minds? How do we keep ourselves safe and narrow? How might we find the courage to ask really openly without knowing why doesn’t the tail go through the window? Thank you very much.

[music]

Marc: I hope you’ve appreciated today’s episode. To learn more about my work and my new book, Finding Clarity, you can visit markcesser.net. This podcast is offered freely and relies on the financial support from listeners like you. Please donate at marclesser.net/donate. Thank you very much.

[00:27:34] [END OF AUDIO]

The post We Are All Poets appeared first on Marc Lesser.

November 16, 2023

Money As a Force For Positive Change with Kristin Hull

Kristin is founder and CEO at Nia Impact Capital. She is a pioneer in the field of impact investing. She is devoted to re-envisioning capitalism, to changing the face of finance, and to promoting inclusion and diversity in leadership.

In our conversation we talk about the importance of understanding money, finance, and investing and the life-changing force that money has. We speak about creating healthy cultures and how Kristin is on the front lines of gender lens investing, both through leading a women-owned company and supporting women-owned companies.

Listen on:

Apple Podcasts

Apple Podcasts  Google Podcasts

Google Podcasts  Podbean App

Podbean App  Spotify

Spotify  Amazom Music

Amazom Music  iHeartRadio

iHeartRadio  Podchaser

Podchaser EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

[music]

[00:00:03] Marc Lesser: Welcome to Zen Bones. This is Marc Lesser. Zen Bones is a biweekly podcast featuring conversations with leading teachers and activists, and an exploration of Zen teachings and practices. Please support our work by making a donation at marclesser.net/donate.

[music]

[00:00:29] Marc: My guest today is Kristin Hull. Kristin is founder and CEO at Nia Impact Capital. She’s a pioneer in the field of impact investing and is re-envisioning capitalism, changing the face of finance and promoting inclusion and diversity in leadership. She founded Nia Community Investments in 2010, and it’s 100% mission-aligned investment fund focused on social justice, environmental sustainability, and she’s based in Oakland, California.

In our conversation today, we talk about the importance of understanding money, finance, and investing, and the life-changing force that money can be. We speak about creating healthy cultures and how Kristin is on the front lines of gender lens investing, both through leading a women-owned company and supporting women-owned companies through investments. I hope you enjoy today’s episode.

[music]

[00:01:36] Marc: I’m very pleased to welcome Kristin Hull. I consider you almost a family member through some of my connections with one of my mentors. Kristin is one of the real pioneers in the realm of impact investing, gender lens investing through Nia Impact Capital. Kristin, good morning.

[00:01:57] Kristin Hull: Good morning, Marc. So nice to be here with you.

[00:02:01] Marc: One of the things that– It’s interesting. I’m teaching a class all day today. It’s a spirit rock based class on mindful leadership. The structure that we’ve been using for that class is the through line and connection between the individual and wellbeing, relationships, and how relationships– what that has to do with creating healthy cultures, and then impact with the larger community in the world. I thought that might be a– We’ll see what happens, but it’s a way I’m thinking of our conversation. I’m curious, what do you do for your own wellbeing these days?

[00:02:53] Kristin: Oh, Marc, it’s such a good question. With the challenging times that our world is going through, figuring out our communities, who are our communities now? Are we feeling the threats of climate change? Are we feeling healthy and well while there’s war in the world? Being able to ground, being able to really check in internally, definitely connecting with nature and taking those times for stillness is really part of my daily routine. Also, really connecting with intention and purpose, which is what we do at Nia, but starting my day in a quiet way, and then also finding those moments in between Zooms and in between busy times to be quiet.

[00:03:33] Marc: I was going to say I made the mistake of, I don’t know, I also have to say I appreciate the practice of reading the newspaper in the morning. Man, here we are, this time of two wars happening. One of the things that really jumped out at me in today’s paper was the buildup of nuclear arms in China. It’s hard to not live in a state of fear, and how to face the challenge, the wars, climate change, nuclear arms, and yet to remain centered, grounded, and even optimistic in the work that we’re doing, and with our children and families. Hard to do. I don’t know how anyone does it without a regular practice of some kind, I have to say.

[00:04:35] Kristin: We definitely see that we all need hope, and I’m one of those that see and believe that action actually brings hope. I mentioned that getting grounded and being still and listening in is really an important part, and yet we’re very much actors. Thinking about the change that we can make and knowing that change really can happen one conversation at a time. We’re very intentional about the conversations we have, be it with clients to empower women with their investing, or with really large corporations about their practices and how they can change to be more equitable. Whether it’s bringing in more diverse leadership, whether it’s being really conscious about their emissions and reporting on their scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions or setting a Paris alignment, we do have these conversations one at a time and in a really conscious and intentional way.

[00:05:31] Marc: I assume you’re aware of it, but I feel your energy so shift when you talk about acting and doing. I’m this funny creature, probably people feel my energy shift when it comes to not doing, but I think both and how we can integrate the non-doing but with the doing, there’s an expression, “Those who do, can.” It’s turning around, “Those who can, do.” What I heard you just saying is, there’s something about doing. There’s something about acting and learning from that. It sounds like you’re really on the front lines. I could feel your energy. The front lines of acting about getting people to rethink the world of money, the world of impact, the world of investing.

[00:06:23] Kristin: Yes. That is our purpose, and that does wake me up in the morning. We have this economy that is very linear, and it works for very few people. For our economy and our world to work for our planet and our people, we really need to make some shifts. Moving into circularity, into reciprocity, to having our economy in Wall Street feel less transactional and more relational is what we’re really about. Really seeing the people behind the ticker symbols and getting to know those people in big corporations, and then also, welcoming people into owning what they own and knowing what they own and ideally, investing to be really proud of what they own.

[00:07:10] Marc: Kristin, I really so appreciate and admire the work that you do and think that it’s so important. Most people, and I feel like I’m still learning, what’s happening with our money? Where do we put our savings? Where do we put our savings accounts, our retirement accounts? Where do companies and colleges put their funds? How important it is how we utilize our money and that you’re in that world having real impact?

I so admire the work that you’re doing around money and the importance of where our money sleeps at night and how our money is active during the day. I know you now have a research team and a mutual fund. I’m interested in learning more about how you decide what companies to invest in, not invest in, and also your theory of change about why this is so important about where we put our money.

[00:08:18] Kristin: Marc, I so appreciate that. Yes. This is what gets me up in the morning and what gets me excited, because in the US and in other places, we’re so separate from our money and yet we really do get the economy that we invest into. That’s how the economy gets created, with dollars. If we can be more conscious about where we’re directing our dollars, we really can have the world that we want to see.

Choosing those companies that are actually working on the transition to our next just and sustainable economy, those companies that are going to be inclusive and build a sense of belonging for their employees, and those that really respect the environment, biodiversity, and all of the things that we need to live safely and in a healthy way on this planet. Building portfolios of those solutions-focused companies, and then really bringing transparency where the financial industry really hasn’t had that. We actually have an interesting history in the US about investments.

With those people coming from Europe, if you think back to pilgrims and that era, those people weren’t just coming to the US forever. They were checking it out to see if it was going to work out and whether they were going to give up what they had in Europe, so they actually had one foot in and one foot out. That meant that a lot of the people that were trying out the US had investments, properties, projects going on in Europe, and they left them in trust with a financial person, a trusted person. As you can imagine, we didn’t have cell phones or computers, so there was very much trust and almost no transparency, and almost no communication about what was happening while they were over here in the US or vice versa.

That legacy of zero transparency and very little communication has carried forward, and that’s almost what we expect about our money. Being conscious about what we own requires more communication and a lot more transparency. We’re working to build that, such that people can be really proud of what they own. They can know what they own, and then be really empowered to direct their money towards those things that they really care about, and the areas of the economy that we need to see grow where there can be a financial return.

[00:10:41] Marc: Yes, it’s interesting. I was noticing, I wrote down as you were speaking, environment, inclusiveness, trust, transparency, and consciousness. Then it’s interesting at the end, you talked about the need for a return. I think there’s been so much tension around retraining all of us, that you can have not only good returns, but great returns by working– well, how we define return.

It’s funny, I remember it used to be that investing in socially responsible companies meant that you were sacrificing a certain return. It’s beautiful how that’s changed, and now there’s the sense that perhaps not only is the return equivalent, but there’s some evidence that you can get an even better return by investing in companies that are working toward the environment, toward this major shift that we’re in the new energy economy especially.

[00:11:52] Kristin: Absolutely, there is. We do need to really check where we’re getting the messaging from. Those people that started that narrative were pretty attached to the status quo investments, and so really understanding where the messaging is coming from and whether there’s any research to back that up. In this case, there wasn’t, and yet the voice was loud, and because many of us are so separated from our investments, and it’s not something we learn about in high school. Last time I checked, California is certainly not one of them. I think there were 11 states that offer required some financial literacy to graduate from high school. College also doesn’t require that.

Even for economics majors, even for MBAs, there isn’t a personal investing component most often, and so this is something that gets passed down sometimes at the dinner table. Often times it’s very patriarchal, like many things in our society and women are left out of those conversations, and so really learning about how to do our investment is something that we often have shame about.

It’s interesting, because, again, we haven’t learned how to do it. There hasn’t been oftentimes an actual curriculum, and yet it’s something we’re expected to do. You think about it, in the US, we have to pay for our bodies, ourselves, our feeding, our home, our clothing, and our families, and yet we’re not taught how to grow that wealth and how to manage it. Is fascinating, I think, just as far as our society.

Breaking that down, what it does, and this is also the patriarchy does play into this, where women in particular feel a certain amount of shame that we don’t know how to do this even though we weren’t taught this. You think about it, I don’t know how to do heart surgery. I didn’t study that, and I don’t have any shame about not knowing how to do that. Similarly, building a skyscraper, don’t have a clue. It doesn’t keep me up at night and I don’t have any shame, and I’m not even sure we should have skyscrapers. I’m not sure how that– At any rate, it’s not something I’ve shame about. Yet, when you talk to most women and many people of color, they carry a lot of shame about not knowing about their investments.

It also keeps us isolated because then we don’t talk about it. At Nia, we’re really encouraging people to talk about their investments. We want to help empower people to talk about it. Then with that consciousness and understanding can come directing it to the things that they really care about that benefit us and society, and will, as you mentioned, have a multiple bottom line. Financial returns, social returns, and environmental returns are what we’re looking for. We absolutely know that companies that are working and really conscious of those areas do really well.

There’s even examples of companies that rather than disposing of waste are looking to recycle that waste or reuse it or partner with another company where there could be a symbiotic exchange where one person’s waste is actually a component needed for something else in another industry or sector. Then they can actually save money and be even more economically smart while they’re being environmentally smart.

There’s a few other examples. Diverse teams make better decisions over 80% of the time. Looking to have a diverse team and leadership, we want short-term thinkers. We want long-term thinkers, and we want everybody at the table to really make the best decisions. We look for that in our companies. We also know that women in leadership bring some really interesting attributes that can be really beneficial to a company. These are some of the things we’re working on at Nia.

[00:15:42] Marc: Do you have some resources in terms of books, podcasts, courses, anything? Like, if someone listening to this says, “Geez, I need to up my education and game here in terms of the world of money and investing.” Anything that top of mind for you?

[00:16:01] Kristin: Sure. I write a money doula blog, The Money Doula. We at Nia are actually just redoing our website. It’ll be out in a couple of weeks. We’ll have many more resources at niaimpactcapital.com. We actually are launching our own podcast as well. We’ll be excited to share different ways to invest with a racial justice and a racial equity lens, and what does that look like and how to do that.

We also write a lot about investing to be gender smart and with a gender lens and centering women in investments, and how that can really play out in a positive way, both for the women and the people doing the investments as well as the financial returns in the companies, et cetera. Thinking about products and services, thinking about leadership, thinking about policies and practices within companies that lead to inclusion and belonging, which generally is better and brings more loyalty for employees, which we really like. Writing a lot. We’ll be having this podcast as well. Then let me think about more resources that I can send.

[00:17:05] Marc: Yes, I look forward to hearing your podcast. I’ve just started reading your blog. It’s interesting, you talked about expertise, skyscrapers or heart surgery, but money it’s just so part of our daily lives that for many of us it’s invisible both in day-to-day, how we work with money. It’s interesting. I noticed. Where was I? I was buying something the other day.

Oh, I took my grandson out for ice cream, and without thinking I opened my wallet and was going to pay in cash, and I realized I’ve not opened my wallet and paid something in cash. I can’t remember the last– It makes me realize how invisible money is, and using a credit card all the time makes it even more invisible. Our savings accounts tend to be a whole another level of invisibility, so I appreciate the work of making it conscious and making our choices conscious at so many different levels.

[00:18:16] Kristin: Thanks, Marc. When you mentioned where is your money sleeping at night, our banks really are doing so much work, and when you’re banking locally at a local bank or a CDFI, they’re sometimes called as well, those banks are loaning out the money. It’s not like we put the money in a deposit and it just sits there. Their business model is that they take that money and then make loans with it, and they’re making a profit while you have a deposit of savings, checking, et cetera. Watching to see where they’re loaning that money can make a really big difference.

Is it going to local businesses in your community, the ice cream shop where you shop, and really putting it into women, people of color, small businesses? That’s what local banks do by charter, by their mission. That’s what their goals are to do, and that’s their business model. Some of the larger banks with the really big name brands, those are multinational banks that largely are financing the fossil fuel industry and other industries that may or may not match your values. Choosing where you bank can be a really big indicator. It can be a really big power move.

When people are shifting banks, I definitely recommend opening the account first at the local place and doing it in steps so that you’re not thinking you’re going to do all this at one time, because the financial industry really does move slowly. Having expectations about how quickly you can align your money with your values, and then getting some coaching and bring a friend. Because the more we can talk about it and share like, “Hey, where are you banking? How’s that working for you? Do you like your bankers?” The more we start talking about that– it’s almost been taboo. We really, in US culture don’t talk about how much money we make.

We certainly don’t talk about how much money we make, and then we don’t talk about where we put it or how we invest it. That’s a stereotype. There are lots of people, particularly Silicon Valley, [unintelligible 00:20:14], Porsche, those people are talking and they’re making deals on the golf course and other places, whereas most of us really aren’t spending that much time sharing our investments with others. The more we can be transparent, conscious, and open about that, I think there’s more change and more conversations where we can make different decisions.

[00:20:35] Marc: I think there’s an enormous room and need for improvement and transparency in this. As you say, how hard it is for people to talk about money. You and I met, I believe we met first at a social venture network, and it was always so curious to me, even in that environment where in some way it was an environment of socially responsible business, consciousness, transparency, almost everything got talked about there except for money. You looked around the room and you knew that there’s some really wealthy people here. There’s some really poor people here.

We have no idea, and it’s interesting the– That’s true. It’s funny even. I lived and I’m still very involved in the Zen community, and money is just one of the things that for the most part, just rarely, rarely gets talked about. I think there’s some shame about it or some– It’s interesting, the secretiveness around wealth and money and where one puts their money. I have to admit, I was a little slow in moving my money out of Wells Fargo and into– I now happily bank with Redwood Credit Union.

It was interesting when I was shifting my accounts, the people who were serving me at Wells Fargo said, “We all bank at Redwood Credit Union, too.” It was so interesting experience, and I just feel better knowing that I’m working with a smaller local bank. I have to say, Wells Fargo was just fine with me, but when you look at where– They’re still investing in the fossil fuel industry.

[00:22:25] Kristin: That’s right. There’s some resources, when you asked about resources, Rainforest Action Network actually puts out a report card of all of the banks every year, and we love that because they really dive in to see who’s funding coal, who’s funding oil, and then they give a report card, and then they also challenge their activism depending on what those grades are, A through F.

I do recommend look up your bank and see how it’s doing. They’re only rating the really large banks, the local banks, pretty much by definition, they can’t actually bid for those large international pipeline projects, so they’re not– Again, by definition, they are lending locally. You brought up something. If you do change, decide to move either advisors, who’s managing your money or your bank, to the extent you feel comfortable.

I do recommend having that conversation and letting people know why. It can be so empowering to have other people know what you’re doing and why. Who knows if you might be inviting a friend. There’s a group of women in New York that have breakup with your bank parties. They have pink t-shirts, they all wear, they bring cupcakes, and they celebrate with the tellers who often are really proud of them, and excited, and they’re often banking somewhere else as well. It can be social and it can actually be fun.

Then I also wanted to just say, just using that voice with your friends and your community, similarly, we use it with the companies that we invest in, offering, almost consulting sometimes and just raising our voice about how we see they could do better, whether it is on tracking their emissions, scopes 1, 2, and 3, and reporting that out in a Paris alignment so that they are really thinking about both the potential risks of climate change, and then also the opportunities, and how could they be part of the solution.

We really do get into conversation and sometimes relationship with them about this. We also raise our voice about diversity, equity, and inclusion issues. I mention this because these conversations do lead to change. We’ve had some really significant changes at some really large companies and some small companies that are really making a difference. When all of us can do this together as far as either choosing an asset manager who wants to be part of the solution, all of us can be part of the solution that way with our money.

[00:24:54] Marc: I love the energy and the action here. It is a realm where we all– I found it very empowering, actually, to have the conversation, “I’m taking my money out because I don’t want to be supporting fossil fuels.” It was interesting to see the people at the bank applaud me. I feel like there’s still so much more work that I can do personally in understanding.

I want to shift a little bit. I’m curious, Kristin, about how you go about– When I think about impact, mostly there’s the impact of the work that you’re doing and how you are engaging in the world of money and companies, but also looking into your own company, some things that you’re doing and learning about building a great culture internally. I wonder how that’s going and how you go about staying aligned with your company values and building a healthy, vibrant working organization. How’s that going and what are some of the best practices that you are doing or learning or wanting to do?

[00:26:04] Kristin: Marc, I really appreciate that. Before the pandemic, we had all sorts of practices. We worked out of a co-working space. Our staff would do yoga at lunchtime, and we would have community meals, and we would have our check-in meetings over breakfast next door at the Black woman-owned restaurant. We had practices that we felt really did unite us. We do support a lot of local nonprofits, and we do sponsor their events, so we do go to those together now.

Largely, we’re working remotely and on screen, and so trying to figure out those practices. One, it starts with hiring– I guess recruitment, actually, about what type of firm we want to be and being really intentional. We’re very different. We’re women-led and women-owned, and of all the asset managers in the US, 0.7%, so less than 1% of the money that’s managed is by a women-led team in a women-owned firm.

Just by being who we are, we’re sending a different message and we’re doing things differently. That has been really interesting as far as our own culture. We also have a Change the Face of Finance internship program where we welcome in young people and teach them about sustainable finance. We teach them about our research methods, and we teach them about how we’re active and how to be engaged with companies and also with our community.

Our practices really do lead a lot to our culture. We also were the very first firm to be gender equity now certified. I thought, “Well, we’re women led, we invest with a gender lens, hand us over the certification.” I thought it would be a pretty quick process. It turns out it was eight months of due diligence on our firm, looking at policies and practices, and it’s all research-based. We learned so much in that process, and our staff got really engaged with that, and so empowering our staff to work on the issues that matter. We’re also a B Corp and having our staff work on that certification process and really tracking and monitoring all of the impact that we’re having as part of our culture.

Then we do team lunches. We’re actually, today, we’ll have a celebratory team lunch. We celebrate birthdays. We also have a star of the week program where each of our staff is the star. All of our staff are the stars, but they get their own special week where they get to direct meetings. We have a company stretch each week that somebody directs and check-ins and checkouts about feelings of how we’re doing, and then also celebrating the milestones, so the small ones.

We have a setting an intention or a purpose for the day where we share a goal for the day, and then we also share a win in our chats, and so everyone gets to share and be celebrated. Changing the face of finance is a long road, and it’s a tough road to be a women-led asset manager, and yet each one of us is playing such a big part that we want to really celebrate each of our team members to the extent that we can over Zoom.

[00:29:14] Marc: I appreciate your energy around and your aspiration to have a really healthy culture. My experience is that it’s humbling and hard to. One of the things I’m fond of saying, which I think is a truism, is that if you’re not building trust in organization, you are building cynicism. That cynicism is easy in places where there’s money and power and hierarchy, and how to completely be, as much as one can, genuine and authentic and caring in the world of work and money takes skill and presence and work, and it feels like you’re wholeheartedly aspiring to walk that path.

[00:29:59] Kristin: We do wake up with intention and purpose, and as you mentioned, it’s really hard. Just connecting each person and building that trust with our staff, with our clients, with our community members and with the companies we invest in.

[00:30:12] Marc: Kristin, I feel like this is part one. Maybe we can at some point continue this conversation, but I just want to thank you for the important– I feel like it’s really important work that you’re doing. I just want to appreciate you as a leader, pioneer, but just as a lovely, lovely human being. Thank you for this time.

[00:30:33] Kristin: Marc, thank you so much. I look forward to following up and having another conversation about this. Really appreciate you.

[music]

[00:30:45] Marc: I hope you’ve appreciated today’s episode. To learn more about my work and my new book, Finding Clarity, you can visit marcLesser.net. This podcast is offered freely and relies on the financial support from listeners like you. Please donate at marclesser.net/donate. Thank you very much.

[music]

[00:31:14] [END OF AUDIO]

The post Money As a Force For Positive Change with Kristin Hull appeared first on Marc Lesser.

November 2, 2023

The Power of Priming

Today’s podcast features The Power of Priming. We begin with a short meditation. Then Marc talks about how the world tends to prime us for anxiety and speed. As an antidote and practice, we can prime ourselves to be present, open, curious, and creative. Meditation practice is a form of priming. We can utilize priming in all parts of our days, from waking up to starting meetings.

Today’s Zen puzzler is based on a quote about staring and impermanence.

Listen on:

Apple Podcasts

Apple Podcasts  Google Podcasts

Google Podcasts  Podbean App

Podbean App  Spotify

Spotify  Amazom Music

Amazom Music  iHeartRadio

iHeartRadio  Podchaser

Podchaser EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Marc Lesser: Welcome to Zen Bones. This is Marc Lesser. Zen Bones is a bi-weekly podcast featuring conversations with leading teachers and activists and an exploration of Zen teachings and practices. Please support our work by making a donation at marclesser.net/donate.

[theme music]

Marc: Today’s podcast features the power of priming. We begin with a short guided meditation, and then I talk about how the world tends to prime us for anxiety and speed. As an antidote and practice, we can prime ourselves to be more present, open, curious, and creative. Meditation practice is a form of priming and we can utilize priming in all parts of our days, from waking up to starting meetings, to any place. Today’s Zen Puzzler is based on a quote about staring and impermanence. I hope you enjoy today’s episode. Let’s do some sitting practice together.

[gong chime]

Marc: Simply stopping. Pausing. Arriving. Just being here. I was saying to someone that I like to start these days my morning meditations with breathing in and breathing in and in and holding my breath, filling up my lungs to capacity, and then exhaling. I was, I was shown this method many years ago in Japan by, I think it was a 93-year-old Zen priest who said this was the secret to his longevity was this daily practice of lung, breath, breathing to capacity, holding the breath, so let’s do that. Simply breathing in and in and in and holding. Holding the breath and whenever you’re ready, releasing and exhaling. Maybe again, breathing in and in and in and in and filling up the lungs and holding, holding, holding, and whenever you’re ready, releasing.

[silence]

Now, just being here with the breath, with the body. Letting go as much as possible of our to-do lists, any sense of comparisons and judgments. Hitting the reset button on our lives right now. Arriving, emptying out, emptying out. Nothing to gain, nothing to lose. Just being fully here. Fully here. No other place. Here, no other time than now. Here, filled with emptying out and filling up with appreciation, with gratitude for being here, alive. Beyond any sense of wholeness or lack of wholeness, radically whole, radically generous.

Acknowledging how much we are given here to receive and to give, receiving and giving. Nothing hidden, nothing folded. Open to receive, open to give. Host and guest, host and guest at the same time. No difference. Keeping it simple. Just coming back to the breath, to the body with radical appreciation. Warm hearted, warm hearted curiosity. I am going to shift gears. You are welcome to continue sitting or stay with me. Whichever feels right for now.

[gong chime]

[theme music]

Marc: I want to talk about priming, the power of priming. In some way, meditation practice is many things, but in some way, it is priming ourselves for warm-hearted curiosity, priming ourselves to live, to think and live and act in a more warm-hearted way, a less dualistic way. Less getting caught by the usual right and wrong or this and that. Of course, of course, we need to, we do live in the ordinary world where right and wrong matter and this and that matter, and our to-do lists matter. There’s something about readying ourselves, priming ourselves, contextualizing things in a way where we emphasize what really matters.

What really matters are our own spirit, our own readiness. Readiness of mind and readiness of heart. There are some really interesting studies that you might be familiar with about priming. There’s one where a group of college students, these were, they were 18 to 22-year-olds, were asked to make sentences using these, using five words. One group was given words like find, it, he, yellow, instantly. Another group were given words that evoked a sense of old age, words like bald, forgetful, Florida, gray, wrinkles.

Then, following this task, each person was instructed to walk down a hallway to participate in another study. In this study, the researchers very unobtrusively measured how long it took for each person to walk. Those who had the old age words like Florida and forgetful and bald took significantly more time to walk down the hallway than the other group. This is the power of priming, and this was called the Florida effect. How simply working with, simply engaging with words that evoke being older influence people’s behavior, influence their thinking even when they had no conscious awareness of the connection. They were asked if they were aware of it, and they weren’t.

Then there was another study in which participants, again, were filling out a form and were asked to make copies. They went to the copy machine and the researchers for one group left a dime on the copy machine. The participants in this study who found the dime reported afterwards that their moods were significantly better moods. We were priming for finding, for receiving. Again, this was a little bit like the meditation that we did earlier is somewhat, in a way, it’s priming ourselves to, we don’t need to find a dime, we can find the eyes of a child or our own hand, or the trees outside, or the sunshine and clouds. We are being gifted. We are being gifted everywhere. It’s using the practice of priming.

We often prime ourselves for a horrendous day or for anxiety, or for what’s missing. Again, this is partly the power of the negativity bias. This more positive priming can be an antidote to the negativity bias, but can also be much more than that. We can consciously use the power of priming to cultivate more awareness, more calmness, more focus. We can prime ourselves by what we read, by what we watch, by the words that we use, and the environment that we create.

We can prime ourselves to be more open-hearted, more empathic, more creative. Of course, we can prime ourselves for stress and anxiety as well. Just being aware, being aware of the power of priming, noticing the words and images in our space, and making sure, as much as we can, to bring in the kinds of words, images that we aspire to. How do we want to show up? How do we want to live?

I was remembering I used to spend a lot of time teaching mindfulness at Google. There was a meeting that was called by some of the leadership at Google and wanted to know, how could we more deeply, more sustainably change the culture here. These were the leaders who were in charge of this mindful leadership program. They were directors fairly high up in the Google hierarchy, wanting to know how, who sincerely wanted to know how to make these kinds of culture changes.