Stewart Brand's Blog, page 75

March 15, 2013

World’s Largest and Oldest Audio Archive

Over the past 12 years, audio archivists at the The Macaulay Library archive at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology have digitized 7,513 hours of analog recordings of natural sounds. The collection houses the largest and oldest scientific archive of biodiversity audio and video recordings, and the entire collection is now accessible online.

These archived recordings started in 1929 when Cornell Lab founder Arthur Allen made the very first recordings of a Song Sparrow at Stewart Park in Ithaca, New York. Since then, the collection has grown to around 150,000 digital audio recordings and represents about 9,000 different species. Clips range from the 1966 recording of an ostrich chick inside its egg to the call of a male walrus:

Once heard, the “coda” song of the male walrus is one of those unforgettable sounds in the world. It is comprised of two basic types of elements, series of evenly-delivered taps followed by an extraordinary bell or gong-like sound. The ringing quality of this latter element is astonishing, especially in an aquatic environment, and that such a sound is produced by a walrus seems all the more improbable (but true). The function is not fully understood, but may convey dominance status to potential mates and rivals.

The Macaulay Library’s goal is to build the most comprehensive collection of natural sounds and to preserve such recordings. There is even an “Audio Most Wanted” list to help build the archive.

March 13, 2013

TEDxDeExtinction: A Primer

This Friday, March 15th, Long Now’s Revive & Restore project, in partnership with the National Geographic Society, are hosting TEDxDeExtinction, an independently organized TED event. To be held at National Geographic’s headquarters in Washington, DC, the event will feature 25 talks about the emerging science of de-extinction.

Speakers include practitioners in the field of molecular biology who are developing new techniques to make de-extinction possible, conservation biologists and ecologists who can speak to the challenges of re-introducing extinct species into the wild, ethicists who wonder if we should even attempt such things, and artists who’ve depicted endangered and extinct species in paintings and photographs.

Researchers around the world have been working to bring back extinct species, and, in fact, have done so on one occasion already. As this science matures, a robust public discussion can help guide de-extinction practitioners along a path that maximizes the benefits of these new capabilities while keeping ethical, social, and ecological concerns in mind. It can also help educate the public. One de-extinction scenario popular in the public imagination is that of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park. In reality, DNA decays at a known half-life and is completely destroyed after 6.8 million years. Cloned dinosaurs, therefore, are not a realistic concern. But the development of this science in secrecy, as depicted in the film, is. With TEDxDeExtinction and other activities, Revive & Restore seeks to support awareness and public comprehension of de-extinction science and to encourage scientists in the field to work openly and collaboratively.

Stewart Brand discussed this emerging field and Revive & Restore at TED 02013:

National Geographic Society authors and researchers are also extensively exploring the implications, challenges and prospects for de-extinction on their website and in the April issue of the Magazine. Among the work is a cover story by author and former SALT speaker Carl Zimmer (previewed on his blog, The Loom), an argument against de-extinction by conservationist Stuart Pimm, and a slideshow of popular revival candidate species such as the Woolly Mammoth.

Reviving any extinct species will be a difficult and long-term project. It will require the consideration of many human, ecological and technological factors. At Pharyngula, Chris Clarke makes a strong case for reviving the Shasta Ground Sloth, a 400-pound cousin of today’s tree-dwelling variety. Through the example of arguing for a particular species, his essay surveys many of the issues de-extinction raises.

TEDxDeExtinction is divided into four sessions: Who, How, Why and Why Not, and Wild Again. It begins at 8:30am EDT on Friday March 15th and you can attend in person, stream it live on the web, find a viewing party to watch with, or wait until the videos are posted online afterwards. We hope you’ll participate in the discussion on Facebook and Twitter. And, for or updates on de-extinction science beyond this week’s TEDx, follow Revive & Restore on Facebook and Twitter.

March 12, 2013

The First 250 years of the “Biblioteca Palatina di Parma”

We’ve got another long-term dispatch from our man-on-the-ground in Italy, Davide Bocelli:

We all know that libraries tend to burn. It has been true for the Library of Alexandria and even for the fictional library of the abbey that Umberto Eco created in his “The Name of the Rose”. In October 02012 a short circuit occurred in one of the oldest galleries of the Biblioteca Palatina di Parma, one of the richest collections of rare and ancient books in the world. The fire stopped just before turning into a cultural disaster. Now the library is closed and inaccessible to the public, so the librarians decided to create a temporary office to keep distributing books, documents and information to a local and international community of students and researchers. Suddenly the mission of this multi-centennial institution has turned from the preservation of books to the preservation of its existence and identity. The economic crisis in Italy has brought deep cuts to the cultural budget of the nation; the expenses to return the library to a safe condition are far beyond the available public funds. The solution is to let the world understand the value, the importance, and the usefulness of such a rich institution in the contemporary world. To some extent, it’s like saying that in the last couple of centuries we learned to take care of the books, now we have to move to the next step – let the people enjoy them.

The Palatina Library has an almost uninterrupted lineage of librarians that dates back to the foundation of the institution in 01761, following the visionary cultural project by Guillame du Tillot, prime minister of the Duke of Parma, Philippe of Bourbon. In 02013 the director is Sabina Magrini, Phd.

The first librarian was Paolo Maria Paciaudi, who used a card catalogue for the first time in Italy. It took 8 years to collect the first set of books and to prepare the galleries in the Pilotta palace in Parma. The rooms and the original shelves were designed by the French architect Ennemond Alexandre Petitot. The Palatina opened to the public in 01769.

The library was named ‘Palatina’ in order to recall the ancient library created inside the Temple of Apollo Palatinus in ancient Rome.

This is the place where you can read an original letter by Galileo Galilei, Niccolò Machiavelli, Martin Luther or Giuseppe Verdi. Here you can read a Divina Commedia by Dante Alighieri in a XIV century illustrated manuscript with miniatures or a Hypnerotomachia Poliphyli in the Manutio’s Edition of 01499.

The book collections started in 01761 continued for centuries. Most of their volumes were bought all over Europe upon the generous funding by Duchess Marie Luise of Austria (01791-01847), wife of Napoleon. It has been a cultural investment for future generations as the collections constitute a unique example in the world’s heritage.

The most remarkable collections of the Palatina Library are:

The Library of Giovanni De Rossi, with 1,432 hebrew codices, Oriental manuscripts and printed books: one of the oldest surviving Jewish libraries in the world;

The Ortalli collection: around 40,000 prints and drawings of German, Italian, Flemish and French art from 15th to 19th centuries;

The typographical material (e.g. the original lead fonts), the editions and the documents belonging to Giambattista Bodoni (01740-01813), one of the most important typographers and type designers of the pre-industrial era.The library contains the Bodoni Museum which is an international bibliographic and research center. Many of the original sets of the Bodoni types are shown in this museum.

It is interesting to see that this difficult moment and the temporary closure will lead the institution to exceed its original scope. While the digitization of the books, prints and manuscripts will decrease the stress on the original artifacts, the institution will concentrate on the local and global communities’ awareness of conservation challenges and the usefulness of humanities research. To reopen the library completely to students and researchers, a major part of the funding will come for the first time in its history, not from the Government but from private donations. Funny enough, in the long run the Library has to explain itself to guarantee its future.

Thanks to:

Sabina Magrini, director of the Palatina Library

Laura Casalis, FAI Parma, The Reopen Palatina Committee

Corrado Mingardi, Library of the Cariparma Foundation in BussetoLinks:

Biblioteca Palatina [Soon in English]

Museo Bodoniano [in Italian]

Reopen Palatina [English]

Thanks, Davide!

March 7, 2013

The Conversation: 1 motorcycle, 9 months, 40 interviews & countless futures

Over much of 02012, Angeus Anderson rode a motorcycle across the United States. Along the way, he recorded conversations with 40 different people espousing diverse critiques of the present and a plethora of visions for the future, “thinkers and doers, from transhumanists to neoprimitivists, urban farmers to musicians.” These interviews, produced by Anderson and Micah Saul, are called The Conversation.

Anderson spoke with Long Now’s Alexander Rose about the 10,000-Year Clock during the early part of his trip. He’s since concluded his travels and reflected on the ideas and perspectives he encountered by mapping the concepts covered to those who discussed them.

Browse all the episodes, or explore the concept map.

March 5, 2013

George Dyson Seminar Primer

Tuesday March 19, 02013 at the Herbst Theater, San Francisco

Photo: Joe Pugliese

George Dyson grew up playing with spare parts from some of the world’s earliest computers at the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study. His father, Freeman Dyson, was one of the original collaborators with John von Neumann and Alan Turing in building these computers, which gave him an early glimpse into the functioning and future of digital technologies. After realizing that computers were going to, in his words, “take over the world”, Dyson built a treehouse in Vancouver to research and build upon indigenous kayak designs. While working in the wilderness, Dyson learned to track the signs of living creatures, but eventually started noticing similar clues in the digital world. The trail he found led him back to civilization, where he began studying the emergence of life-like systems within computers. By now, organic metaphors have saturated the digital landscape, but Dyson formulated, supported and propagated these metaphors well before they’d entered the mainstream.

Often called “an historian among futurists”, George Dyson’s scholarship carefully digs into the recent past to understand what lies before us. His first book, Darwin Among The Machines, gives a prehistory of computing, charting the characters that brought the computer into existence. His most recent book, Turing’s Cathedral, is the culmination of years of deep research into his childhood home, The Institute for Advanced Study. Dyson picks up where he left off in Darwin Among the Machines to examine the culture, structures, decisions, and people that led to the first computers and atomic weapons. Not merely history, Dyson explores what computers actually do when we’re using them and even while we aren’t:

We have created this expanding computational universe, and it’s open to the evolution of all kinds of things. It’s cycling faster and faster, and it’s way, way, way more than doubling in scale every year. Even with the help of Google and YouTube and Facebook, we can’t consume it all. And we aren’t really aware what this vast space is filling up with. From the human perspective, computers are idle 99 percent of the time, just waiting for the next instruction. While they’re waiting for us to come up with instructions, more and more computation is happening without us, as computers write instructions for each other. And as Turing showed mathematically, this space can’t be supervised. As the digital universe expands, so does this wild, undomesticated side.

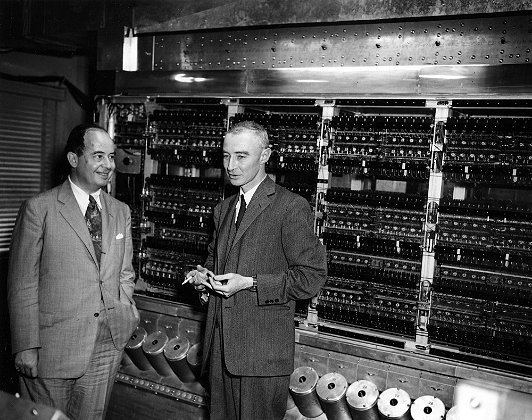

Photo: John von Neumann and J. Robert Oppenheimer in front of MANIAC, the computer that was built at the Institute for Advanced Study during Dyson’s childhood. Photo Credit.

When we turned on the first computer, we turned on a universe—a computational universe. In this universe, numbers are not merely descriptors, but also actors. They send instructions to other packets of numbers that generate more numbers, ad infinitum:

Like our own universe at the beginning, it’s more exploding than expanding. We’re all so immersed in it that it’s hard to perceive … You can’t predict how software will behave by inspecting it. The only way you can tell is to actually run it. And this fundamental unpredictability means you can never have a complete digital dictatorship with one government or company controlling our digital lives—not because of politics but because of mathematics. There will always be codes that do unpredictable things. This is why the digital universe will never be a national park; it will always be an undomesticated, unpredictable wilderness. And that should be reassuring to us.

George Dyson will discuss the digital universe and how it affects our notions of time on March 19th at the Herbst Theatre on Van Ness. You can reserve tickets, get directions, and sign up for the podcast on the Seminar page. If you are a member, please check your email for special ticketing instructions.

Subscribe to the Seminars About Long-term Thinking podcast for more thought-provoking programs.

March 4, 2013

From Flood Control to Controlled Flooding

When a devastating flood destroyed much of the southwestern Netherlands in 01953, its government decided it was time for action. Over the next few decades, the nation poured research and financial resources into the construction of the Deltawerken, a massive network of dams and storm barriers that now protects the country’s lowest lying provinces from the kinds of floods that are encountered once in a millennium – and even against those that might occur once every 10,000 years.

As Long Now’s Alexander Rose explained in a 02011 blog post, the Maeslant barrier – one of the largest man-made moving structures in the world – has already begun to repay the cost of its construction by offering the Rotterdam port protection from surging seas on multiple occasions. It has been an example of effective water management for other low-lying regions of the world.

But these days, it seems the Netherlands are changing their approach to the battle with rising sea levels. Faced with continuing climate change, the Dutch are responding not by raising the height of their barriers, but by breaking through their dykes. As New York Times reporter Michael Kimmelman recently explained,

“… the evidence is leading them to undertake what may seem, at first blush, a counterintuitive approach, a kind of about-face: the Dutch are starting to let the water in. They are contriving to live with nature, rather than fight (what will inevitably be, they have come to realize) a losing battle. Why? The reality of rising seas and rivers leaves no choice. Sea barriers sufficed half a century ago, but they’re disruptive to the ecology and are built only so high, while the waters keep rising. American officials who now tout sea gates as the one-stop-shopping solution to protect Lower Manhattan should take notice. In lieu of flood control the new philosophy in the Netherlands is controlled flooding.”

In other words, the Dutch approach is no longer one of fighting the inevitable consequences of climate change, but rather of strategically harnessing natural resources to mitigate its impact on human life. The government’s new focus is a project called Room for the River, a $3 billion investment in land redevelopment. What was once agricultural land is now being transformed into multipurpose flood plains and spillways. Farms have been displaced, and polders are converted into recreational nature zones that can hold overflow from surging rivers if need be.

“By lowering the dike along the northern edge of the two-square-mile Overdiepse Polder, the Bergse Maas canal will be able to spill in [to the polder], diminishing the water level in the canal by a foot, enough to spare the 140,000 residents of Den Bosch, upriver, in the event of once-every-25-year floods. By displacing farmers, in other words, residents in that city can breathe a little easier.”

The cost-benefit analysis adds up, but needless to say, the project has left some farmers quite unhappy. In negotiation with the government, they were able to settle on a compromise: a series of mounds would be built at the edges of the floodplains, on which at least some of the displaced farms could be rebuilt.

Kimmelman sees a lesson here: an efficient response to climate change requires compromise and tough decisions. In other words: it calls for a collective engagement in long-term thinking, and a willingness to make the necessary sacrifices.

“[G]ood government makes those decisions while giving affected residents adequate knowledge and agency: the ability to make choices, and the responsibility to live by them. Politically that may be trickier than commissioning sea barriers or making dikes into boardwalks or redesigning waterfronts and neighborhoods to accommodate floods and storms. But it’s necessary. And it may be the most important lesson that the Netherlands has to offer at the moment.”

March 1, 2013

Long Now Board Members at TED 02013

This year’s TED conference has two of Long Now’s board members presenting, Stewart Brand and Danny Hillis. Although the videos will not be published on the TED site until later this year, some attendees graciously summarized and illustrated the talks for the rest of us. The cartoons below come from Fever Pitch, a group of artists that put information in illustrated form. You can find the rest of their TED illustrations on their Facebook page.

De-Extinction

Stewart’s talk introduces the concept of de-extinction to the TED community. First giving an overview of the technology and previous research, he goes on to explain how the newly launched Revive & Restore project is working on bringing back other extinct species, starting with the passenger pigeon. Revive & Restore will be hosting TEDxDeExtinction in Washington DC on March 15th to further explore this project.

The Internet Needs a Plan B

Danny’s talk calls for the creation for a plan B in the case of internet failure. Michael Copeland from Wired also gives a good summary of the key points of the talk for those that were not physically present.

Chris Anderson Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

The Makers Revolution

Tuesday February 19, 02013 – San Francisco

Video is up on the Anderson Seminar page for Members.

*********************

Audio is up on the Anderson Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

Desktop manufacturing changes world – a summary by Stewart Brand

We’re now entering the third industrial revolution, Anderson said. The first one, which began with the spinning jenny in 1776, doubled the human life span and set population soaring. From the demographic perspective, “it’s as if nothing happened before the Industrial Revolution.”

The next revolution was digital. Formerly industrial processes like printing were democratized with desktop publishing. The “cognitive surplus” of formerly passive consumers was released into an endless variety of personal creativity. Then distribution was democratized by the Web, which is “scale agnostic and credentials agnostic.” Anyone can potentially reach 7 billion people.

The third revolution is digital manufacturing, which combines the gains of the first two revolutions. Factory robots, which anyone can hire, have become general purpose and extremely fast. They allow “lights-out manufacturing,” that goes all night and all weekend.

“This will reverse the arrow of globalization,” Anderson said. “The centuries of quest for cheaper labor is over. Labor arbitrage no longer drives trade.” The advantages of speed and flexibility give the advantage to “locavore” manufacturing because “Closer is faster.” Innovation is released from the dead weight of large-batch commitments. Designers now can sit next to the robots building their designs and make adjustments in real time.

Thus the Makers Movement. Since 2006, Maker Faires, Hackerspaces, and TechShops (equipped with laser cutters, 3D printers, and CAD design software) have proliferated in the US and around the world. Anderson said he got chills when, with the free CAD program Autodesk 123D, he finished designing an object and moused up to click the button that used to say “Print.” This one said “Make.” A 3D printer commenced building his design.

Playing with Minecraft, “kids are becoming fluent in polygons.” With programs like 123D Catch you can take a series of photos with your iPhone of any object, and the software will create a computer model of it. “There is no copyright on physical stuff,” Anderson pointed out. The slogan that liberated music was “Rip. Mix. Burn.” The new slogan is “Rip. Mod. Make.”

I asked Anderson, “But isn’t this Makers thing kind of trivial, just trailing-edge innovation?” “That’s why it’s so powerful,” Anderson said. “Remember how trivial the first personal computers seemed?”

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

How long is humanity’s future?

Much like the Centre for Existential Risk at Cambridge, the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford spends significant effort grappling with scenarios that could lead to the human species’ demise.

The Institute is headed by Nick Bostrom, a scholar of philosophy, physics, computational neuroscience, and mathematical logic. Aeon Magazine’s Ross Anderson recently spoke with Bostrom and several other researchers at the Institute to ask what kinds of risks we should really be taking seriously:

The risks that keep Bostrom up at night are those for which there are no geological case studies, and no human track record of survival. These risks arise from human technology, a force capable of introducing entirely new phenomena into the world.

Studying risk of any kind leads inevitably to questions of statistics and probability – things human intuition is generally very very bad at comprehending. Fortunately, what nature did not give us, we can still nurture in ourselves. Bostrom is relentless is his mathematical and logical approach to the probability of different possibilities and the utility they afford the human race. Depicting his utilitarian approach, Anderson paraphrases Bostrom’s explanation for why studying existential risk is so valuable:

We might be 7 billion strong, but we are also a fire hose of future lives, that extinction would choke off forever. The casualties of human extinction would include not only the corpses of the final generation, but also all of our potential descendants, a number that could reach into the trillions.

Read: Omens by Ross Anderson

February 28, 2013

Encapsulated Universes

In a recent conversation with Edge, Stanford Psychologist and former SALT speaker Lera Boroditsky explores intriguing – and still controversial – questions about the relationship between the language we speak, and the way we think about the world.

Weaving her thoughts together with examples from a variety of different languages, Boroditsky shows us that languages differ in the kind of contextual information they prioritize. Hebrew assigns everything in the world a gender, whereas Finnish does not. Russian verbs specify when an event took place, while Indonesian verbs are timeless. And where English sentences can be vague about the causality of an event, Japanese tends to be much more explicit about who did what. In other words, language shapes the things we notice about our environment.

“Think about it this way. We have 7,000 languages. Each of these languages encompasses a world-view, encompasses the ideas and predispositions and cognitive tools developed by thousands of years of people in that culture. Each one of those languages offers a whole encapsulated universe. So we have 7,000 parallel universes, some of them are quite similar to one another, and others are a lot more different.”

This does not mean that language dictates what we do and do not experience about our world – speakers of Finnish are still able to recognize the difference between men and women, and Indonesians know whether something happened in the past or the present. But it does mean that language is more than simply a way to convey meaning. In prioritizing certain pieces of information over others, language adds a certain color to our universe. In other words, meaning emerges from the fabric of language itself:

“Those interconnections between words are not simply the webbing on top of an otherwise pure logical knowledge system. Rather, in fact, meaning exists in the way that we use words; the patterns of word use create the system of meaning. There’s no getting away from language in getting to complex meanings.”

Exploring a new language, then, is truly a way to explore new worlds – and to celebrate the “flexibility and the ingenuity of the human mind.”

“The fact that we’re able to take so many different perspectives and create such an incredibly diverse set of ways of looking at the world, that is something first to be celebrated, but also something to learn from: flexibility and diversity are at the very heart of what makes us human and what makes us so smart. I think the more we understand how people are able to take all these different perspectives, and able to change the way they think, the better we’ll understand the nature of being human.”

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers