Stewart Brand's Blog, page 73

April 24, 2013

Wait for it.

There have been many comic strips that run for a long long time, but rarely does a single entry take on a prodigious life of its own. Randall Munroe has been publishing xkcd since 02005 - not a bad run – and regularly stretches the medium’s definition. Entries can range from a single panel, to massive informational charts. From the beginning of the strip, time, and vast quantities of it, has been a common theme. One recent foray into this subject matter garnered the strip a mention, alongside Long Now, in The Economist because it’s been updating for almost a month now.

“Time,” as the piece is called, started off as a single panel with two people sitting on a beach. xkcd’s punchlines are generally hidden in the image’s title text, but in this case it simply says “Wait for it.” Every half-hour the image is updated, forming a very, very slow animation. (Most animated films, for instance, move along at 24 frames per second; this is more like .0006 frames per second.) The characters have been building a sandcastle and fortifying it against a rising sea since March 25th, 02013. You can see the whole thing, sped up, on Explain xkcd, a wiki created about the comic.

The eventual fate of the sandcastle and its creators, as well as the ultimate length of this story, remain unknown. Wait for it.

Stewart Brand Seminar Tickets

Seminars About Long-term Thinking

Stewart Brand on “Reviving Extinct Species”

TICKETS

Tuesday May 21, 02013 at 7:30pm SFJAZZ Center

Long Now Members can reserve 2 seats, join today! General Tickets $15

About this Seminar:

Death is still forever, but extinction may not be—at least for creatures that humans drove extinct in the last 10,000 years. Woolly mammoths might once again nurture their young in northern snows. Passenger pigeon flocks could return to America’s eastern forest. The great auk may resume fishing the coasts of the northern Atlantic.

New genomic technology can reassemble the genomes of extinct species whose DNA is still recoverable from museum specimens and some fossils (no dinosaurs), and then, it is hoped, the genes unique to the extinct animal can be brought back to life in the framework of the genome of the closest living relative of the extinct species. For woolly mammoths, it’s the Asian elephant; for passenger pigeons, the band-tailed pigeon; for great auks, the razorbill. Other plausible candidates are the ivory-billed woodpecker, Carolina parakeet, Eskimo curlew, thylacine (Tasmanian tiger), dodo, Xerces blue butterfly, saber-toothed cat, Steller’s sea cow, cave bear, giant ground sloth, etc.

The Long Now Foundation has taken “de-extinction” on as a project called “Revive & Restore,” led by Ryan Phelan and Stewart Brand. They organized a series of conferences of the relevant molecular biologists and conservation biologists culminating in TEDxDeExtinction, held at National Geographic in March. They hired a young scientist, Ben Novak, to work full time on reviving the passenger pigeon. He is now at UC Santa Cruz working in the lab of ancient-DNA expert Beth Shapiro.

This talk summarizes the progress of current de-extinction projects (Europe’s aurochs, Spain’s bucardo, Australia’s gastric brooding frog, America’s passenger pigeon) and some “ancient ecosystem revival” projects—Pleistocene Park in Siberia, the Oostvaardersplassen in the Netherlands, and Makauwahi Cave in Kaua’i. De-extinction has been described as a “game changer” for conservation. How might that play out for the best, and how might it go astray?

In an era of “anthropocene ecology,” is it now possible to repair some of the deepest damage we have caused in the past?

April 23, 2013

Nicholas Negroponte Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

Beyond Digital

Wednesday April 17, 02013 – San Francisco

Audio is up on the Negroponte Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

A world of convergence – a summary by Stewart Brand

In education, Negroponte explained, there’s a fundamental distinction between “instructionism” and “constructionism.” “Constructionism is learning by discovery, by doing, by making. Instructionism is learning by being told.” Negroponte’s lifelong friend Seymour Papert noted early on that debugging computer code is a form of “learning about learning” and taught it to young children.

Thus in 2000 when Negroponte left the Media Lab he had founded in 1985, he set out upon the ultimate constructionist project, called “One Laptop per Child.” His target is the world’s 100 million kids who are not in school because no school is available. Three million of his laptops and tablets are now loose in the world. One experiment in an Ethiopian village showed that illiterate kids can take unexplained tablets, figure them out on their own, and begin to learn to read and even program.

In the “markets versus mission” perspective, Negroponte praised working through nonprofits because they are clearer and it is easier to partner widely with people and other organizations. He added that “start-up businesses are sucking people out of big thinking. So many minds that used to think big are now thinking small because their VCs tell them to ‘focus.’”

As the world goes digital, Negroponte noted, you see pathologies of left over “atoms thinking.” Thus newspapers imagine that paper is part of their essence, telecoms imagine that distance should cost more, and nations imagine that their physical boundaries matter. “Nationalism is the biggest disease on the planet,” Negroponte said. “Nations have the wrong granularity. They’re too small to be global and too big to be local, and all they can think about is competing.” He predicted that the world is well on the way to having one language, English.

Negroponte reflected on a recent visit to a start-up called Modern Meadow, where they print meat. “You get just the steak—no hooves and ears involved, using one percent of the water and half a percent of the land needed to get the steak from a cow.” In every field we obsess on the distinction between synthetic and natural, but in a hundred years “there will be no difference between them.”

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

The Doctor Prescribes Brian Eno

Last week Long Now board member Brian Eno unveiled two new installations at Montefiore Hospital in Hove, England. The pieces are designed to be soothing for patients in the hospital and provide a sense of respite from the harsh realities of its clinical environment. In the lobby of the new hospital, Eno’s 77 Million Paintings will be on permanent display. The artwork, like the chime sequence for the 10,000 year clock, uses generative music techniques pioneered by Eno to ensure endless unique combinations of video and music to relax the viewer.

The other work in the hospital is a quiet room for patients of the hospital that plays a new ambient album by Eno entitled Quiet Room for Montefiore. The album will only be able to be heard in the hospital, somewhat of a hurdle for serious Eno fans. News of the installation has spread quickly, and Eno’s spokesman has confirmed that four other hospital architects are currently in conversation with Eno about putting similar rooms into the hospitals they are currently building. In talking about the new turn, Eno notes that this projects flowed quite naturally from his previous works:

“It seemed a natural step for me to take as I’ve been dealing with this idea of functional music for quite a few years.”

For those that won’t be able to make it to England, Brian Eno’s 77 Million Paintings will also go on display in New York at the Red Bull Music Academy from May 3rd until June 2nd.

A recently released interview from Alfred Dunhill also gives a glimpse into Eno’s general philosophy and approach to art:

April 22, 2013

Our Digital Afterlives

In 02006, Long Now Board Member David Eagleman wrote in Nature:

There is no afterlife, but a version of us lives on nonetheless.

At the beginning of the computer era, people died with passwords in their heads and no one could access their files. When access to these files was critical, companies could grind to a halt. That’s when programmers invented death switches.

With a death switch, the computer prompts you for your password once a week to make sure you are still alive. When you don’t enter your password for some period of time, the computer deduces you are dead, and your passwords are automatically e-mailed to the second-in-command. Individuals began to use death switches to reveal Swiss bank account numbers to their heirs, to get the last word in an argument, and to confess secrets that were unspeakable during a lifetime.

In other words, a “death switch” is a way for us to pre-program an afterlife for our digital selves. Despite the relatively short lifespan of software platforms, it is likely that the data we post on the internet will live on – somewhere – after we ourselves expire.

Eagleman, along with several others, is urging us to think about what will happen to our digital legacy after death: to decide where we want our data to live, and who will have the privilege to engage with it. Do we want to place our legacy in the hands of an heir, or do we want our online presence to be erased? Alternatively, do we perhaps want to designate our own computers as executors of our estate, and have it send out friendly messages to our descendants every once in a while?

Over the past two years, a series of Digital Death Day “unconferences” has brought people together to talk about these kinds of questions. Evan Carroll and John Romano published a book and host an accompanying blog about ways to shape our digital afterlives. And most recently, Google introduced its Inactive Account Manager: a new tool that allows you to decide what will happen to your emails, photo albums, posted videos and personal profiles when your account becomes inactive.

Planning for our digital beyond is a way to save our own lives from receding into a digital dark age – and as such, it may be a way to keep something of ourselves alive after our bodies die. Eagleman muses:

This situation allows us to forever revisit shared jokes, to remedy lost opportunities for a kind word, to recall stories about delightfully earthly experiences that can no longer be felt. Memories now live on their own, and no one forgets them or grows tired of telling them. We are quite satisfied with this arrangement, because reminiscing about our glory days of existence is perhaps all that would have happened in an afterlife anyway.

April 17, 2013

Almost half of the world’s languages are endangered

On the blog of Long Now’s Rosetta Project, intern Karin Wiecha describes the recently published findings of a major linguistics research effort:

ELCat uses the metaphor of biodiversity to illustrate the gravity of the loss of an entire language family: If we compare the extinction of a language to the extinction of an animal species, the death of a language family would equal the loss of a whole branch of the animal kingdom, for example all felines.[4] We know of a hundred language families that have gone extinct over the course of history – 24% of the world’s linguistic diversity. But the fact that 28 of them have gone extinct over the relatively short time span of the last 50 years is symptomatic of the accelerated rate of language loss we are experiencing in recent times.

The Endangered Languages Catalogue (ELCat) “aims to compile a comprehensive up-to-date catalogue on all languages considered to be in danger.” At the 3rd International Conference on Language Documentation & Conservation (ICLDC 3) earlier in 02013, ELCat’s director presented several years’ worth of research, including the above facts.

Beyond those that we’ve already lost, ELCat has found that 457 languages – almost 10% of humanity’s living languages – are spoken by just 10 or fewer people and are on the brink of extinction, while 3,176 – almost half – are endangered. In fact, ELCat puts the current rate of linguistic extinction at about one language every three months.

Learn more, including what people are doing about it, on the Rosetta Blog.

April 11, 2013

Humanity’s Last Game

Former SALT speaker and professor of religion James Carse distinguishes between “finite” and “infinite” games:

“A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the game.”

We might think of games as things we ‘play’ – as make-believe universes in which we might wander around for a period of time, engaged in activities that have little to no bearing on our ordinary lives. But ordinary life can, in many ways, also be thought of as a form of ‘play’. In the real world, too, we (mostly) play by the rules; we employ strategies in order to achieve certain objectives, and we interact with fellow players.

At last week’s Game Developer’s Conference, designer Jason Rohrer presented a new game that brings all these different dimensions of ‘play’ together. In response to a design challenge prompt that asked developers to come up with “the last game that humanity will ever play,” Rohrer designed a game that is both infinite and finite, lived and ‘played’ – and very, very long term.

Rohrer’s game is intended not to be played for another 2,000 years. In order to ensure its longevity, he built its board and pieces out of solid machined titanium. Anticipating a temporal language barrier between himself and future generations, he wrote the game’s instructions in the form of symbols and visual diagrams.

In order to ensure that the game would not be played before its time, Rohrer buried it at a precise but unknown location in the Nevada desert – and turned the process of finding it into a game itself. At his conference presentation, Rohrer gave each member of his audience a sheet that listed 900 unique GPS coordinates. Taken together, these handouts contained a million possible locations, only one of which corresponds to the game’s actual site. If one person checks one of these GPS coordinates each day, it is guaranteed that the game will be found within one million days, or 2,737 years.

In the last chapter of The Clock of the Long Now, Stewart Brand writes that

“Infinite games are corrupted by inappropriate finite play. Governance (infinite) is disabled when factional combat (finite) becomes the whole point instead of providing helpful debate and alternation of power. Cultures (infinite) perish when one culture seeks to eradicate another. Nature (infinite) is dangerously disrupted when commercial competition (finite) lays waste to natural cycles. Finite games flourish within infinite games, but they must not displace them, or all the games are over.” (1999:161).

Rohrer has not only taken this to heart, but has in fact taken it a step further: the finite board game he has buried in the desert is ultimately intended to be the simple starting point for the infinite game of long term thinking.

April 9, 2013

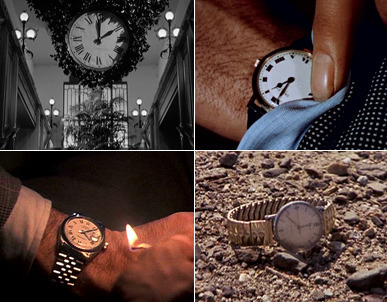

Christian Marclay’s “The Clock” at SFMOMA

On Saturday, April 6th, the SFMOMA opened Christian Marclay’s “The Clock”.

The exhibit is a 24-hour long film that consists of snippets from the past 70 years of cinematic history–the clips all unified by the common trait of having clocks or referencing a time of day in them. To accomplish this task, Marclay hired a team of assistants that watched films and gathered sections that included a clock or watch, eventually compiling a repository of thousands of clips that were sorted by time. Marclay, whose past work has included remixing and DJ-ing, stitched together the clips into a 24-hour video collage. The scenes range from hospitals and car chases to bedrooms and restaurants, all spliced together and reminding us of the role of time in narrative.

The film is meant to be played for 24 hours straight, with the time on the clocks in the film perfectly matching the actual time of day. In this sense the entire piece is a clock itself, as well as a meditation on how we use clocks - it implicitly asks for 24 hours of your time, yet you spend the entire film literally watching the minutes tick by.

One of the central objectives of the Clock of the Long Now is to encourage people to think about deep time and how it has and will shape the world around us. In contrast, Marclay’s piece emphasizes the small moments that make up life–waiting for someone at a restaurant, realizing that you’re late to an appointment, suddenly waking up at 4am. By mashing these moments together into a full day of disorienting situations, Marclay asks us to contemplate just what it is that creates our unified sense of these moments.

The exhibit will be shown until June 2nd. During this time, there will be several 24 hour screenings for those that want see the work in it’s entirety.

April 8, 2013

Whole Earth Psychology

Anyone who has traveled abroad or simply eaten at the ethnic restaurant around the corner will appreciate the richness of cross-cultural diversity our world has to offer. Each part of the world has its own cuisine, its own social organization, its own religious practices, and its own fashions. Cognitive research has always assumed that underneath this incredible diversity, humans nevertheless all have the same basic wiring: even if we believe in different things, we ultimately possess the same cognitive skills and respond to external stimuli in similar ways.

Anthropological research, however, suggests that culture reaches much further down into our brains. In a recent feature for the Pacific Standard, Ethan Watters suggests that

The most interesting things about cultures may not be in the observable things they do – the rituals, eating preferences, codes of behavior, and the like – but in the way they mold our most fundamental conscious and unconscious thinking and perception.

In the early twentieth century, anthropologists realized that culture affects not just the way we behave, but also the way our mind engages with the world. Inspired by developments in psychoanalysis, these scholars began to explore how personality and psychological functioning are shaped by the cultural environment. Margaret Mead, for example, famously argued that the experience of adolescence on Samoa bears little resemblance to what we know of American teenagers, debunking the assumption that the wrought experience of puberty is the result of purely biological factors. A few decades later, Robert Levy and Jean Briggs showed that culture affects the way we experience and express emotion; and the work of scholars like Mel Spiro and Rick Shweder has stimulated research on how the human sense of self is shaped by the cultural environment.

Watters features the more recent work of anthropologist Joe Henrich, who took this line of scholarship a step further by combining ethnographic work with cognitive research methods. In 02010, he co-authored an article in which he showed that responses to classic cognitive tests (such as the Müller-Lyer Illusion) in fact vary across cultures. In other words: even the human modes of reasoning and perception that we believed to be universal are in fact uniquely shaped by our cultural environment.

Cognitive skills, Henrich and his colleagues argue, are not hardwired into our brains at all: there is considerable cross-cultural variation in the way we respond to and make sense of environmental stimuli. We develop these divergent cognitive styles because the worlds we grow up in vary so widely from one another. Think of the vast differences between the world of lower Manhattan, say, and a remote village in the Himalayan mountains; or between a capitalist society and a socialist state. A New Yorker’s perception of lines, colors, and distances will differ considerably from that of a Nepali, just as a Frenchman and a North Korean may not agree about the definition of “fairness.” Though we are all born with the same brain, that soft tissue is shaped by our environment as we develop our cognitive capacities and socialize into our community. And that environment is inevitably, indelibly shaped by the culture of which we are a part. Like language, we might think of culture as an “encapsulated universe.”

Henrich’s research unsettles decades of cognitive research, and not just because it debunks the idea of a universal pattern of human functioning. As it turns out, the particular population commonly studied by psychologists and economists lies at the very edges of the “human bell curve.”

Economists and psychologists, for their part, did an end run around the issue with the convenient assumption that their job was to study the human mind stripped of culture. The human brain is genetically comparable around the globe, it was agreed, so human hardwiring for much behavior, perception, and cognition should be similarly universal. No need, in that case, to look beyond the convenient population of undergraduates for test subjects. A 2008 survey of the top six psychology journals dramatically shows how common that assumption was: more than 96% of the subjects tested in psychological studies from 2003 to 2007 were Westerners – with nearly 70 percent from the United States alone. Put another way: 96 percent of human subjects in these studies came from countries that represent only 12 percent of the world’s population.

Henrich and his colleagues refer to this population of college students as WEIRD – not only because they happen to be Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic, but also because this population turns out to be such an outlier. Henrich’s research proves that American modes of perception are not the rule, but a radical exception to it. Watters writes:

It is not just our Western habits and cultural preferences that are different from the rest of the world, it appears. The very way we think about ourselves and others – and even the way we perceive reality – makes us distinct from other humans on the planet, not to mention from the vast majority of our ancestors. Among Westerners, the data showed that Americans were often the most unusual, leading the researchers to conclude that “American participants are exceptional even within the unusual population of Westerners – outliers among outliers.” Given the data, they concluded that social scientists could not possibly have picked a worse population from which to draw broad generalizations. Researchers had been doing the equivalent of studying penguins while believing that they were learning insights applicable to all birds.

Watters suggests that it may be one of those uniquely Western psychological features that led us to believe that our cognitive functioning is free of culture. Looking upon ourselves as free and autonomous individuals, we’ve come to assume that while we may live inside a culture, our essence somehow exists beyond – and independently of – its bounds.

Not only does Henrich’s research argue that we are not as free of culture as we had believed; his research shows that a true understanding of human psychology – and even of brain functioning – must always take a larger view, and reach beyond the familiarity of our own immediate environment.

April 4, 2013

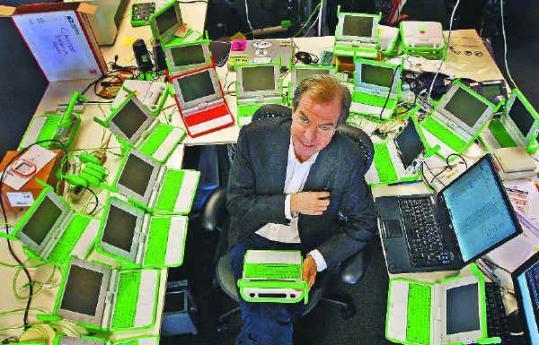

Nicholas Negroponte Seminar Primer

Wednesday April 17, 02012 at the Marines’ Memorial Theater, San Francisco

Nicholas Negroponte has made a name for himself not just by predicting the future, but by creating it. He co-founded and, for 15 years, directed the MIT Media Lab, which has become the premier academic incubator for advanced technologies research in fields like mesh networks, personalized robotics, and human computer interaction.

During his time at MIT, Negroponte was the first investor in Wired Magazine, for which he authored a series of contributions that eventually became the book “Being Digital”. Collectively, these writings offered a glimpse into the world we now occupy–complete with ubiquitous wireless data, touch screens, e-books and personalized news.

One of Negroponte’s intellectual themes is the evolution and measures of education. He favors an educational approach that teaches children to “learn learning” and to become passionate about topics that interest them, believing that the current model is outdated, alienating and stifling to natural curiosity. This vision led him to leave the Media Lab to found “One Laptop Per Child”. The reasoning behind the project stemmed from one of Negroponte’s mantras:

“When I wake up in the morning, I ask myself one question, and that question is: Will normal market forces do what I am doing today? And if the answer is yes, stop.”

Ten years ago, laptops were not dropping in price. As Intel increased processing speeds, Windows increased their processing requirements, which kept the price of a basic laptop near $1,000 and the digital divide insurmountable for many.

Negroponte’s mission was to create a $100 laptop that could be given to children in poor countries with struggling education systems to allow for a new type of educational boost. Ten years later, he has distributed 2.5 million computers across the world, and cheap computers have become an established norm.

It will take many years to fully determine the effect of these 2.5 million laptops, but Negroponte’s work has been a major driver in the narrowing of the digital divide.

His vision of low-cost laptops proliferating across the developing world is just one example of the kind of long-view thinking that has made Negroponte an effective leader, mover and shaker in the world of technology and access to it. Another might be the eponymous Negroponte switch, which he describes (and extrapolates upon) below.

Negroponte’s last column for WIRED, written in 1998, was entitled “Beyond Digital”. On April 19th at Marines’ Memorial Theater he resurrects this title to give us a glimpse of the possibilities that lie ahead. You can reserve tickets, get directions, and sign up for the podcast on the Seminar page. If you are a member, please check your email for special ticketing instructions.

Subscribe to the Seminars About Long-term Thinking podcast for more thought-provoking programs.

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers