Stewart Brand's Blog, page 78

February 6, 2013

Researchers theorize new method of highly precise atomic timekeeping

Albert Einstein discovered that time is woven into the fabric of space. Now, Berkeley researcher Holger Müller suggests that time is woven into matter, as well.

Interested in determining the simplest possible way of measuring time, Müller has discovered a way to turn matter into a natural clock.

“When I was very young and reading science books, I always wondered why there was so little explanation of what time is,” said Müller, who is also a guest scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “Since then, I’ve often asked myself, ‘What is the simplest thing that can measure time, the simplest system that feels the passage of time?’ Now we have an upper limit: one single massive particle is enough.”

This is not an atomic clock in the traditional sense; rather than measuring the energy emissions of electrons, Müller’s timekeeper looks at atoms as a whole by making use of a particular feature of matter: its building blocks behave like both particles and waves.

Quantum mechanics was born when physicists decided that light was neither a wave (as argued by Huygens) nor a beam of particles (as Newton thought), but both. In 1924, De Broglie discovered that this duality was true for all forms of matter, and developed a formula to calculate the wavelength of different particles.

Müller theorized that if you can find a way to measure these wavelengths experimentally – if you can construct a clockwork to count an atom’s oscillations – you have a very fundamental unit of time. Unfortunately, these atomic frequencies (also known as Compton frequencies) still outpace our best instruments of detection. But Müller has found a possible solution in yet another one of Einstein’s discoveries. Because motion slows the passage of time, a moving atom oscillates at a slower pace than a stationary one. The difference between the two frequencies may be measurable, and thereby give us a unit of time.

Though Müller’s mechanism is not yet as precise as an atomic clock, improvement of the design will increase its accuracy. Either way, the implications are far-reaching. If matter can be used to count time, the reverse is also true: time can become a unit of measurement for matter. In other words: Müller’s work shows that time is woven into the most fundamental building blocks of our world. One might even say it’s what we’re made of.

February 1, 2013

Long Data: Predicting Solar Storms

As Samuel Arbesman’s recent article on Long Data might suggest, all the data in the world on the Sun’s activities today can’t tell us what it will do tomorrow. But careful observation over the last several centuries has allowed us to develop a predictive understanding of the patterns in solar storm activity. This collection of long data and the insights it provides won’t guarantee you only see ads that are relevant to you, but it does keep our global electrical and telecommunications infrastructure running.

Long Now intern Sandy Curth writes:

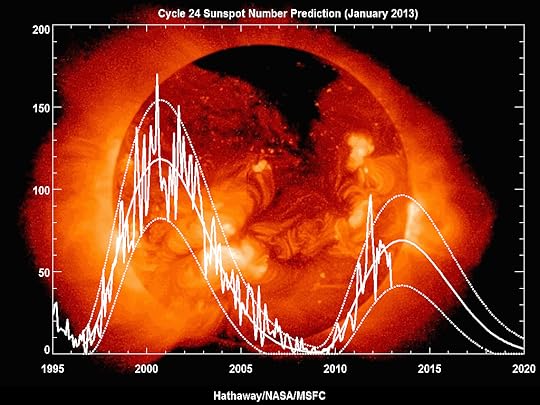

Researchers at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center recently posted their solar cycle predictions for 02013. This coming fall is predicted to be the peak of the twenty-fourth 11- year sunspot cycle on record. Though that might sound scary, this peak is actually anticipated to be the lowest since 01906. While the expected solar activity and its impacts for this year aren’t likely to break many records, the source of these predictions is an exceptional example of long term thinking with data stretching back over 350 years.

Since the start of the 18th century, astronomers have been consistently noting the number of spots on the sun, with records of sunspot observation dating back to 364BCE in the star catalogue of Chinese astronomer Gan De. Belgium’s Solar Influences Data Analysis Center offer sunspot data yearly from 01700, monthly from 01750 and daily beginning in 01874. Modern solar predictions are created by analyzing trends in this data and measuring activity in the Earths magnetic field caused by the sun.

NASA solar physicist Dr. David Hathaway explains the details:

A number of techniques are used to predict the amplitude of a cycle during the time near and before sunspot minimum. Relationships have been found between the size of the next cycle maximum and the length of the previous cycle, the level of activity at sunspot minimum, and the size of the previous cycle.

Among the most reliable techniques are those that use the measurements of changes in the Earth’s magnetic field at, and before, sunspot minimum. These changes in the Earth’s magnetic field are known to be caused by solar storms but the precise connections between them and future solar activity levels is still uncertain.

Another indicator of the level of solar activity is the flux of radio emission from the Sun at a wavelength of 10.7 cm (2.8 GHz frequency). This flux has been measured daily since 1947. It is an important indicator of solar activity because it tends to follow the changes in the solar ultraviolet that influence the Earth’s upper atmosphere and ionosphere. Many models of the upper atmosphere use the 10.7 cm flux (F10.7) as input to determine atmospheric densities and satellite drag.

Predicting the behavior of a sunspot cycle is fairly reliable once the cycle is well underway (about 3 years after the minimum in sunspot number occurs [see Hathaway, Wilson, and Reichmann Solar Physics; 151, 177 (1994)]). Prior to that time the predictions are less reliable but nonetheless equally as important. Planning for satellite orbits and space missions often require knowledge of solar activity levels years in advance.

Even though many of the Sun’s systems are still a mystery, scientists are able to predict its activity well enough to keep our communication satellites on track and give us time to prepare for powerful geomagnetic storms that can black out whole cities.

The first solar storm recorded was in September of 01859 and reportedly caused major failures in the world’s developing telegraph system and auroras as far south as the Caribbean. More recently, a less severe storm in 01989 left six million Canadians without power for nine hours. Predicting the next major solar event is becoming as important to maintaining our infrastructure as predicting the next hurricane.

Taking the past seriously is a clear route to a good prediction, but having the presence of mind to collect seemingly useless data to make predictions easier for future thinkers is worth contemplating. Astronomers centuries ago did not have tangible applications for the data they recorded on the sun. Luckily, though, they took the time to carefully collect and compile what they could see so that today, as scientists realize the potentially devastating impact of a severe solar storm, their data becomes priceless.

January 31, 2013

Samuel Arbesman on the importance of long-term data

Digital data is exploding in volume and there’s enough money in making sense of it all that it’s garnered its own buzzword lately: big data. In an increasingly measurable world, data-sets of unprecedented size and comprehensiveness are turning up new and genuinely exciting insights. Applied Mathematician Samuel Arbesman points out, though, that many of these data-sets are but snapshots, when it’s timelapse videos we need to really understand something:

Why does the time dimension matter if we’re only interested in current or future phenomena? Because many of the things that affect us today and will affect us tomorrow have changed slowly over time: sometimes over the course of a single lifetime, and sometimes over generations or even eons.

Datasets of long timescales not only help us understand how the world is changing, but how we, as humans, are changing it — without this awareness, we fall victim to shifting baseline syndrome. This is the tendency to shift our “baseline,” or what is considered “normal” — blinding us to shifts that occur across generations (since the generation we are born into is taken to be the norm).

Arbesman spoke last year at a Salon event at The Long Now Foundation on his book, The Half-Life of Facts. He explained that there are patterns in the ways our scientific knowledge changes over time. Much of what we take to be true today has a half-life: it will decay at a predictable rate as new science overturns our current understanding. Long data, of the type he champions in this recent article, is essential to unearthing these types of insights and avoiding a static understanding of a dynamic world.

(The image above is a page from a notebook of Isaac Newton’s.)

January 29, 2013

Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

The Statues Walked — What Really Happened on Easter Island

Thursday January 17, 02012 – San Francisco

Video is up on the Hunt and Lipo Seminar page for Members.

*********************

Audio is up on the Hunt and Lipo Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

Easter Island reconsidered – a summary by Stewart Brand

In the most isolated place on Earth a tiny society built world-class monuments. Easter Island (Rapa Nui) is 1,000 miles from the nearest Pacific island, 3,000 miles from the nearest continent. It is just six by ten miles in size, with no running streams, terrible soil, occasional droughts, and a relatively barren ocean. Yet there are 900 of the famous statues (moai), weighing up to 75 tons and 40 feet high. Four hundred of them were moved many miles from where they were quarried to massive platforms along the shores.

Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo began their archeological work on Easter Island in 2001 expecting to do no more than add details to the standard morality tale of the collapse of the island’s ecology and society—Polynesians discovered Rapa Nui around 400-800AD and soon overpopulated the place (30,000 people on an island the size of San Francisco); competing elites cut down the last trees to move hundreds of enormous statues; after excesses of “moai madness” the elites descend into warfare and cannibalism, and the ecology collapses; Europeans show up in 1722. The obvious lesson is that Easter Island, “the clearest example of a society that destroyed itself“ (Jared Diamond), is a warning of what could happen to Earth unless we learn to live with limits.

A completely different story emerged from Hunt and Lipo’s archaeology. Polynesians first arrived as late as 1200AD. There are no signs of violence—none of the fortifications common on other Pacific islands, no weapons, no traumatized skeletons. The palm trees that originally covered the island succumbed mainly to rats that arrived with the Polynesians and ate all the nuts. The natives burned what remained to enrich the poor soil and then engineered the whole island with small rocks (“lithic mulch”) to grow taro and sweet potatoes. The population stabilized around 4,000 and kept itself in balance with its resources for 500 years until it was totally destroyed in the 18th century by European diseases and enslavement. (It wasn’t Collapse; it was Guns, Germs, and Steel.)

What was up with the statues? How were they moved? Did they have a role in the sustainable balance the islanders achieved? Hunt and Lipo closely studied the statues found along the moai roads from the quarry. They had D-shaped beveled bottoms (unlike the flat bottoms of the platform statues) angled 14 ° forward. The ones on down slopes had fallen on their face; on up slopes they were on their back. The archeologists concluded they must have been moved upright—”walked,” just as Rapa Nuians long had said. No tree logs were required. Standard Polynesian skill with ropes would suffice.

“Nova” and National Geographic insisted on a demonstration, so a 5-ton, 10-foot-high “starter moai” replica was made and shipped to Hawaii. After some fumbling around, 18 unskilled people secured three ropes around the top of the statue—one to each side for rocking the statue, one in the rear to keep it leaning forward without falling. “Heave! Ho! Heave! Ho!” they cry in the video, the statue rocks, dancing lightly forward, and the audience at Cowell Theater erupts with applause. Progress was fast, even hard to stop—100 yards in 40 minutes. A family could move one.

Stone statues to ancestors are common throughout Polynesia, but the enormous, numerous moai of Easter Island are unique in the world. Were they part of the peaceful population control and conservative agriculture regime that helped the society “optimize long-term stability over immediate returns” in a nearly impossible place to live?

During the Q & A, Hunt and Lipo were asked how their new theory of Easter Island history was playing on the island itself. Shame at being the self-destructive dopes of history has been replaced by pride, they said. Moai races are being planned. Polynesians were the space explorers of the Pacific. They completed discovering every island in the huge ocean by the end of the 13th century, colonized the ones they could, and then stopped.

Easter Island is not Earth. It is Mars.

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

January 28, 2013

Chris Anderson Seminar Tickets

Seminars About Long-term Thinking

Chris Anderson on “The Makers Revolution”

TICKETS

Tuesday February 19, 02013 at 7:30pm Lam Research Theater at YBCA

Long Now Members can reserve 2 seats, join today! General Tickets $10

About this Seminar:

Chris Anderson’s book THE LONG TAIL chronicled how the Web revolutionized and democratized distribution. His new book MAKERS shows how the same thing is happening to manufacturing, with even wider consequences, and this time the leading revolutionaries are the young of the world. Anderson himself left his job as editor of Wired magazine to join a 22-year-old from Tijuana in running a typical Makers firm, 3D Robotics, which builds do-it-yourself drones.

Web-based collaboration tools and small-batch technology such as cheap 3D printers, 3D scanners, laser cutters, and assembly robots, Anderson points out, are transforming manufacturing. Suddenly, large-scale manufacturers are competing not just with each other on multi-year cycles, they are competing with swarms of tiny competitors who can go from invention to innovation to market dominance in a few weeks. Anybody can play; a great many already are; a great many more are coming.

“Today,” Anderson writes, “there are nearly a thousand ‘makerspaces’— shared production facilities— around the world, and they’re growing at an astounding rate: Shanghai alone is building one hundred of them.”

“Open source,” he adds, “is not just an efficient innovation method— it’s a belief system as powerful as democracy or capitalism for its adherents.”

Launch of the LDCM: Continuing 40 years of Landsat Data

In 1972, NASA launched its first Landsat satellite into orbit. This February, it will launch its eighth.

The new satellite is part of the Landsat Data Continuity Mission, a collaboration between NASA and USGS that will continue adding to 40 years worth of data about the Earth’s surface.

In what is now the longest-running project of collecting satellite imagery of Earth, Landsat data offer an important resource for a variety of endeavors: from cartography to natural disaster management; urban planning to the monitoring of natural resource usage. Moreover, the unprecedented continuity of data offers invaluable insight into the way that Earth has been changing over the past 40 years.

Landsat 8 will be the most advanced of them yet, promising not just the continuation of data collection, but more precise data that will enrich ongoing geological, ecological, and geographical research.

January 24, 2013

Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

The Statues Walked — What Really Happened on Easter Island

Thursday January 17, 02012 – San Francisco

Audio is up on the Hunt and Lipo Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

Easter Island reconsidered – a summary by Stewart Brand

In the most isolated place on Earth a tiny society built world-class monuments. Easter Island (Rapa Nui) is 1,000 miles from the nearest Pacific island, 3,000 miles from the nearest continent. It is just six by ten miles in size, with no running streams, terrible soil, occasional droughts, and a relatively barren ocean. Yet there are 900 of the famous statues (moai), weighing up to 75 tons and 40 feet high. Four hundred of them were moved many miles from where they were quarried to massive platforms along the shores.

Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo began their archeological work on Easter Island in 2001 expecting to do no more than add details to the standard morality tale of the collapse of the island’s ecology and society—Polynesians discovered Rapa Nui around 400-800AD and soon overpopulated the place (30,000 people on an island the size of San Francisco); competing elites cut down the last trees to move hundreds of enormous statues; after excesses of “moai madness” the elites descend into warfare and cannibalism, and the ecology collapses; Europeans show up in 1722. The obvious lesson is that Easter Island, “the clearest example of a society that destroyed itself“ (Jared Diamond), is a warning of what could happen to Earth unless we learn to live with limits.

A completely different story emerged from Hunt and Lipo’s archaeology. Polynesians first arrived as late as 1200AD. There are no signs of violence—none of the fortifications common on other Pacific islands, no weapons, no traumatized skeletons. The palm trees that originally covered the island succumbed mainly to rats that arrived with the Polynesians and ate all the nuts. The natives burned what remained to enrich the poor soil and then engineered the whole island with small rocks (“lithic mulch”) to grow taro and sweet potatoes. The population stabilized around 4,000 and kept itself in balance with its resources for 500 years until it was totally destroyed in the 18th century by European diseases and enslavement. (It wasn’t Collapse; it was Guns, Germs, and Steel.)

What was up with the statues? How were they moved? Did they have a role in the sustainable balance the islanders achieved? Hunt and Lipo closely studied the statues found along the moai roads from the quarry. They had D-shaped beveled bottoms (unlike the flat bottoms of the platform statues) angled 14 ° forward. The ones on down slopes had fallen on their face; on up slopes they were on their back. The archeologists concluded they must have been moved upright—”walked,” just as Rapa Nuians long had said. No tree logs were required. Standard Polynesian skill with ropes would suffice.

“Nova” and National Geographic insisted on a demonstration, so a 5-ton, 10-foot-high “starter moai” replica was made and shipped to Hawaii. After some fumbling around, 18 unskilled people secured three ropes around the top of the statue—one to each side for rocking the statue, one in the rear to keep it leaning forward without falling. “Heave! Ho! Heave! Ho!” they cry in the video, the statue rocks, dancing lightly forward, and the audience at Cowell Theater erupts with applause. Progress was fast, even hard to stop—100 yards in 40 minutes. A family could move one.

Stone statues to ancestors are common throughout Polynesia, but the enormous, numerous moai of Easter Island are unique in the world. Were they part of the peaceful population control and conservative agriculture regime that helped the society “optimize long-term stability over immediate returns” in a nearly impossible place to live?

During the Q & A, Hunt and Lipo were asked how their new theory of Easter Island history was playing on the island itself. Shame at being the self-destructive dopes of history has been replaced by pride, they said. Moai races are being planned. Polynesians were the space explorers of the Pacific. They completed discovering every island in the huge ocean by the end of the 13th century, colonized the ones they could, and then stopped.

Easter Island is not Earth. It is Mars.

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

January 23, 2013

Time and the End of History Illusion

According to a team of psychologists at Harvard, we’re poor predictors of our own future.

In a paper published last week in Science, these researchers report on a study that asked participants to estimate how much their personality, tastes, and values had changed over the last decade, and how much they expected they would change in the next. Statistical analysis reveals what these psychologists call an “End of History Illusion”: while we remember our past selves to be quite different from who we are today, we nevertheless believe that we won’t change much at all in the future. The New York Times quotes:

“Middle-aged people – like me – often look back on our teenage selves with some mixture of amusement and chagrin,” said one of the authors, Daniel T. Gilbert, a psychologist at Harvard. “What we never seem to realize is that our future selves will look back and think the very same thing about us. At every age we think we’re having the last laugh, and at every age we’re wrong.”

There are several ways to explain these findings. It’s more difficult to predict the future than to recall the past; perhaps participants simply weren’t willing to speculate on something they felt uncertain about. It’s also possible that study participants overestimated how much they had changed in the past, making it seem as though they were underestimating their change in the future. However, the psychologists suggest that the end of history illusion is most probably explained by the fact that it just makes us feel better about ourselves:

… most people believe that their personalities are attractive, their values admirable, and their preferences wise; and having reached that exalted state, they may be reluctant to entertain the possibility of change. People also like to believe that they know themselves well, and the possibility of future change may threaten that belief. In short, people are motivated to think well of themselves and to feel secure in that understanding, and the end of history illusion may help them accomplish these goals. (Science 339:98).

This “end of history” notion has some history of its own. For example, Stanford political scientist and former SALT speaker Francis Fukuyama follows Marx in arguing that civilization as a whole has come to the end of a 10,000-year history of development. With the advent of liberal democracy, he writes in 1989, we’ve reached the pinnacle of social evolution:

What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government. This is not to say that there will no longer be events to fill the pages of Foreign Affair’s yearly summaries of international relations, for the victory of liberalism has occurred primarily in the realm of ideas or consciousness and is as yet incomplete in the real or material world. But there are powerful reasons for believing that it is the ideal that will govern the material world in the long run.” (The National Interest).

On the other hand, French postmodern philosopher Jean Beaudrillard contends that Fukuyama’s modernist theory is no more than an illusion caused by our particular relationship with time. He writes that contemporary civilization has simply “lost” its sense of history:

… one might suppose that the acceleration of modernity, of technology, events and media, of all exchanges – economic, political, and sexual – has propelled us to ‘escape velocity’, with the result that we have flown free of the referential sphere of the real and of history. … A degree of slowness (that is, a certain speed, but not too much), a degree of distance, but not too much, and a degree of liberation (an energy for rupture and change), but not too much, are needed to bring about the kind of condensation or significant crystallization of events we call history, the kind of coherent unfolding of causes and effects we call reality. Once beyond this gravitational effect, which keeps bodies in orbit, all the atoms of meaning get lost in space. Each atom pursues its own trajectory to infinity and is lost in space. This is precisely what we are seeing in our present-day societies, intent as they are on accelerating all bodies, messages and processes in all directions and which, with modern media, have created for every event, story and image a simulation of an infinite trajectory. Every political, historical and cultural fact possesses a kinetic energy which wrenches it from its own space and propels it into a hyperspace where, since it will never return, it loses all meaning. No need for science fiction here: already, here and now – in the shape of our computers, circuits and networks – we have the particle accelerator which has smashed the referential orbit of things once and for all. (1994:1-2).

Illusion or not, the Harvard study shows that a sense of being at the end of history has real-world consequences: underestimating how differently we’ll feel about things in the future, we sometimes make decisions we later come to regret. In other words, the end of history illusion could be thought of as a lack of long-term thinking. It’s when we fail to consider the future impact of our choices (and imagine alternatives) that we lose all sense of meaning, and perhaps even lose touch with time itself.

January 22, 2013

A conversation with Laura Cunningham and Ryan Phelan

Join artist and ecologist Laura Cunningham and Ryan Phelan at the David Brower Center in Berkeley on Wednesday evening, January 30th, for a conversation jointly presented by The Long Now Foundation and the Brower Center. “A Landscape Flux” will blend Laura Cunningham’s long-term perspective on California ecological history with Ryan Phelan’s work, including a new Long Now project on extinct species revival, Revive and Restore.

The talk marks the conclusion of Laura Cunningham’s exhibit at the Brower Center, “Before California.” The exhibit is based on her artistic reconstructions of the region’s ecological history, published in the book A State of Change: Forgotten Landscapes of California. In October 02011, Laura Cunningham presented the talk “Ten Millennia of California Ecology” as one of The Long Now Foundation’s Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

We hope to see you at the talk, which is free and open to the public. Please see the Brower Center website for details, and Brown Paper Tickets to RSVP.

In conversation with Ryan Phelan of The Long Now Foundation, Laura Cunningham will explore the theme of changing natural landscapes and time’s effect on them, reminding us that the landscapes we see today are merely a snapshot of an ever-changing world in constant flux.

A Landscape Flux

The David Brower Center

6:30 pm to 9:00 pm Wednesday, January 30th, 02013

Conversation with Laura Cunningham and Ryan Phelan: 7:00 – 8:00

Book Signing in the Gallery: 8:00 – 9:00

Visit the gallery by the end of January to see Laura Cunningham’s exhibit.

Laura Cunningham: Before California

The David Brower Center

Hazel Wolf Gallery (Fourth Annual Art/Act Exhibition)

Exhibit dates: September 13, 02012 – January 30, 02013

January 16, 2013

Edge Question 02013

This year’s Edge question is up, and it has the usual breadth of analysis we have come to expect over the years. For the uninitiated, Edge.org is one of the best not-so-secret secrets of the internet. Founded in 01996 by John Brockman, Edge asks a “big picture” question every year to scholars who think about systemic issues in creative ways. The answers have always been enlightening, and it has always been worth a few hours of time to read through them each year. This year, as in past years, the Long Now Board is well represented, as well as the scholars who’ve spoken in our lecture series.

The question this year is “What *should* we be worried about?”. Below you will find the responses of Long Now affiliates, although we also recommend reading through the rest of the responses.

Long Now Board:

Daniel Hillis wonders about the filtering effects of semantic search.

Brian Eno calls us to reflect on our persistent aversion to politics.

Kevin Kelly discusses the long term effects of aging populations.

Paul Saffo worries about the partisan ideology surrounding technological advances.

Esther Dyson asks us to consider the ethical and political questions surrounding greater predictive power in health and medicine.

SALT speakers:

Nassim Taleb would prefer those with massive wealth and power have more “skin in the game.”

Martin Rees hopes we can avoid weaponizing (purposely or not) bio- and nano-tech.

Craig Venter wants the public to understand vaccines only work if we all get them.

Tim O’Reilly reminds us to be vigilant of anti-intellectualism in times of economic stress.

Bruce Sterling thinks whatever we worry about, it shouldn’t be the Singularity.

Vernor Vinge doesn’t want us to think we’ve escaped Mutually Assured Destruction.

Sam Harris hopes those designing our institutions will carefully take into account the incentives they create.

Daniel Everett worries about the future of academic scholarship with the rise of online courses.

Matt Ridley warns against superstition both against and within science.

George Dyson thinks we need a low-tech redundant backup internet in case of emergencies.

Juan Enriquez wonders how we are going to navigate our increasingly large digital fingerprints.

Steven Pinker talks about the threats to peace that get often get overlooked.

Mary Catherine Bateson wants us to properly frame our worries so that we can act on them accordingly.

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers