Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 89

May 15, 2011

fave pix

My friend Kate is visiting with her daughter—she's the same age I was when I first came to Brooklyn back in the '70s! These are my two favorite shots so far:

at the Central Park Children's Zoo; practicing for Halloween

at the Central Park Children's Zoo; practicing for Halloween

May 13, 2011

for the birds

You no doubt know that I have a thing for birds. Well, today I got my fill at the Museum of Natural History and then the Central Park zoo. Don't ask me to name any of these birds, however…

May 12, 2011

no consensus

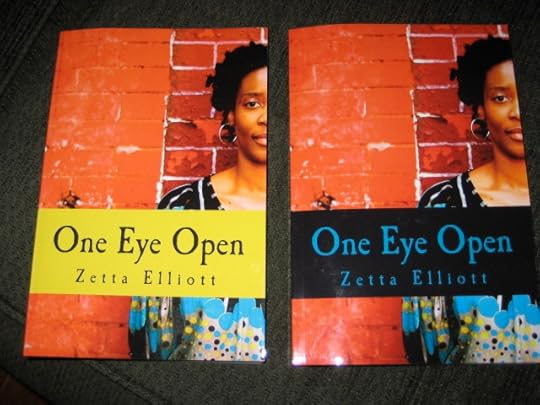

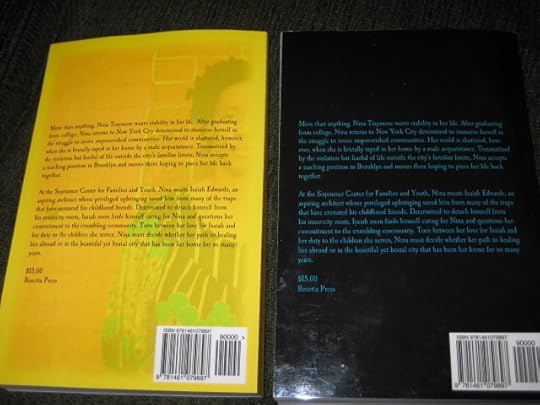

Folks on Facebook seem to be split—nearly everyone on my personal account likes the yellow cover and everyone on my author account likes the black…you?

The black cover has an opaque back, whereas the yellow cover allows the front image to be visible on the back.

May 11, 2011

non-race-driven multicultural titles

Elizabeth Bluemle is an activist bookseller who's trying to effect change within the publishing community. Stop by her Shelftalker blog if you know of titles that might fit her criteria:

Elizabeth Bluemle is an activist bookseller who's trying to effect change within the publishing community. Stop by her Shelftalker blog if you know of titles that might fit her criteria:

Stories and nonfiction about racially charged eras and issues of racial identity in our culture are critical, of course. But equally important are mainstream stories—in every genre—that feature kids of color as main characters in a setting that, like most of America, is culturally and racially diverse. Stories about friendship, family, pets, love, character, self-reliance, etcetera, in mysteries, adventures, science fiction and fantasy, for every age child and every type of book, including chapter books, board books, easy readers.

I'll be interested in seeing how many 2011 titles publishers put forward. Out of the 5000 books published annually for children, how many do you think are "non-race-driven multicultural titles"? I'm working on an essay right now about the challenges I face when trying to be an "ethical author." How do you act with integrity in a homogeneous industry that seems only to value the bottom line? I want my conclusion to offer solutions, and this is my big idea: every year at BookExpo, the publishing community should come together to focus exclusively on equity. We need librarians, teachers, authors, illustrators, publishers, editors, agents, art directors, booksellers, marketing directors, book reviewers, book buyers, and literacy advocates to commit to a set of ethical, equitable standards—like those outlined in the UK Publishing Equalities Charter. We need members of the publishing community to become signatories—to make a solid commitment to taking concrete actions AND to posting their results. That way we can track progress and offer support and resources when signatories fall short of their goals. It's not enough to rely on folks' good intentions. Not when all the evidence proves that goodwill, if and when it exists, simply isn't enough.

May 10, 2011

The Ethical Author?

In the summer of 2009 I got an unusual email from Amazon—not an advertisement or order confirmation, but a personal email. This message came from an acquisitions editor who had read my novel, A Wish After Midnight, which I had self-published the year before. This editor said he loved the book and wanted to partner with me to help it find a larger audience. After verifying that it wasn't a hoax, I entered into negotiations and ultimately sold the rights to my novel to AmazonEncore, the company's new publishing wing. Wish was given a beautiful new cover and was re-released six months later in early 2010.

As a black feminist, I definitely had reservations about partnering with a behemoth like Amazon. I worried what my friends would say—would they accuse me of selling out? Was I betraying my feminist values? Yet, I reasoned, I had spent nearly a decade dealing with rejection from big and small publishers alike. My work was even turned down by a feminist press that was headed by a black woman! I didn't embrace self-publishing at the outset—I was driven to it by the refusal of traditional publishers to give my writing their official stamp of approval. Self-publishing ensured that my work would exist in the world, but I still encountered a great deal of resistance and a certain measure of disdain, and it was still a real challenge to get my books into the hands of readers and reviewers.

In the end, to my relief, most of my feminist friends congratulated me on my decision to work with Amazon and did all they could to spread the word about my "new" novel. I had a fantastic experience collaborating with the AmazonEncore team—I was treated with respect, my expertise and ideas were valued, and no changes were made to my feminist narrative about two black teenagers sent back in time to Civil War-era Brooklyn. Wish wasn't reviewed in any major outlets, but the blogosphere embraced it and my overall experience was so positive that I plan to publish my next YA novel with AmazonEncore in 2012.

I'm still determined, however, to keep all options on the table when it comes to publishing. The industry is in flux right now, and I think authors need to respond by being flexible and open to new possibilities. We also need to be conscious of the ways that certain voices continue to be marginalized within the publishing community. Statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children's Book Center demonstrate that authors of color constitute only 5% of the five thousand books published annually for young readers. Getting published is an uphill battle for most writers, but the institutional racism that pervades all sectors of US society makes it that much harder for people of color to have their stories published by traditional houses. Self-publishing has been an important option for black writers for centuries, and I suspect that won't change any time soon.

The first time I spoke publicly about self-publishing was at Rutgers University. After reviewing my award-winning picture book, Bird, Dr. Yana Rodgers invited me to present before her students in the Women and Gender Studies Department. She assigned my self-published play, Mother Load, and I developed a presentation that featured my sheroes, Barbara Smith, Audre Lorde, and June Jordan. I talked about Second Wave black feminist publications and the historical importance of Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. I explained my decision to start my own imprint, Rosetta Press, which is committed to publishing books "that reveal, explore, and foster a black feminist vision of the world." Finally I read aloud June Jordan's prophetic words about the "difficult miracle" of being a black writer in the US:

…we have been rejected and we are frequently dismissed as "political" or "topical" or "sloganeering" and "crude" and 'insignificant" because, like Phillis Wheatley, we have persisted for freedom. We will write against South Africa and we will seldom pen a poem about wild geese flying over Prague, or grizzlies at the rain barrel under the dwarf willow trees. We will write, published or not, however we may, like Phillis Wheatley, of the terror and the hungering and the quandaries of our African lives on this North American soil. And as long as we study white literature, as long as we assimilate the English language and its implicit English values, as long as we allude and defer to gods we "neither sought nor knew," as long as we…remain the children of slavery, as long as we do not come of age and attempt, then to speak the truth of our difficult maturity in an alien place, then we will be beloved, and sheltered, and published.

But not otherwise. And yet we persist.

I've written quite extensively about racism in the publishing industry and the risks and rewards of self-publishing. But when aspiring authors ask me how to deal with rejection, I tell them to persist: Keep writing. Get your work done so that when the moment arrives, you'll be ready. Study the industry, know what you're up against. But don't surrender your voice. You may have to adjust your expectations, and you may find yourself forming unexpected alliances. But stay in the game and stand with others who are trying to change the rules.

In a couple of weeks the publishing industry will convene in NYC for the annual BookExpo America. My goal now—in between self-publishing a new novel and finishing a new manuscript—is to replicate the UK Publishing Equalities Charter proposed by the Diversity in Publishing Network (DIPNET).

emerging

I don't drink, and that means I can probably count on one hand the number of times I've been inside a bar. I'm not very social and I'm running on fumes as we near the end of the semester. Yesterday wasn't a good day for me health-wise, but I got myself together and arrived at Franklin Park Bar & Beer Garden for last night's "Myth & Magic" reading. And I'm *so* glad I did! Penina Roth, the fabulous series coordinator and hostess, made me feel at ease and introduced me to many of the local writers and booklovers who were in attendance. I got to meet and enjoy the readings given by my fellow authors, including Canadian Alexi Zentner who gave me sound advice on how to get noticed by the literary powers that be in Canada. When it was my turn to read I stood instead of perching on the stool and tried to remember to *look* at the audience—which was hard b/c of the bright light aimed right at my eyes. But even if I couldn't see people's faces, I could sense that they were listening. Sometimes Wish feels old to me—after all, I wrote it more than seven years ago. But when you read aloud and bring your words to life, you realize how much you still care about your characters and how they rely on you to let them breathe and speak in the world. Last night I decided not to read the entire section I'd prepared and by the time I sat down and let my eyes get used to the bar's dim lighting, several people had come up to talk about the book. I signed one copy purchased immediately by an enthusiastic reader, and met another woman who had seen me read before and invited me to contribute to her YA anthology on bullying. We took a group photo, I thanked Penina, and then walked home. If you're a writer, do consider submitting your work for a future reading—the bar is newly renovated, it has an outdoor space, and you can grab a burger if you're hungry. I plan to go back with friends—being social isn't easy for me, but it's almost always worth the effort. Writers need readers, and it's easy for me to forget that part of my job as an author is to introduce my characters to the "real world." I've got the latest proof of One Eye Open and imagined myself reading that novel aloud to an audience at Franklin Park in the future…

I don't drink, and that means I can probably count on one hand the number of times I've been inside a bar. I'm not very social and I'm running on fumes as we near the end of the semester. Yesterday wasn't a good day for me health-wise, but I got myself together and arrived at Franklin Park Bar & Beer Garden for last night's "Myth & Magic" reading. And I'm *so* glad I did! Penina Roth, the fabulous series coordinator and hostess, made me feel at ease and introduced me to many of the local writers and booklovers who were in attendance. I got to meet and enjoy the readings given by my fellow authors, including Canadian Alexi Zentner who gave me sound advice on how to get noticed by the literary powers that be in Canada. When it was my turn to read I stood instead of perching on the stool and tried to remember to *look* at the audience—which was hard b/c of the bright light aimed right at my eyes. But even if I couldn't see people's faces, I could sense that they were listening. Sometimes Wish feels old to me—after all, I wrote it more than seven years ago. But when you read aloud and bring your words to life, you realize how much you still care about your characters and how they rely on you to let them breathe and speak in the world. Last night I decided not to read the entire section I'd prepared and by the time I sat down and let my eyes get used to the bar's dim lighting, several people had come up to talk about the book. I signed one copy purchased immediately by an enthusiastic reader, and met another woman who had seen me read before and invited me to contribute to her YA anthology on bullying. We took a group photo, I thanked Penina, and then walked home. If you're a writer, do consider submitting your work for a future reading—the bar is newly renovated, it has an outdoor space, and you can grab a burger if you're hungry. I plan to go back with friends—being social isn't easy for me, but it's almost always worth the effort. Writers need readers, and it's easy for me to forget that part of my job as an author is to introduce my characters to the "real world." I've got the latest proof of One Eye Open and imagined myself reading that novel aloud to an audience at Franklin Park in the future…

On Sunday I had the pleasure of meeting an editor from Ms.—the only magazine I subscribe to! I'm hoping to write something for their blog on what it means to be an ethical author. But right now I've got grading to do…

May 6, 2011

achieving equity in publishing

Sometimes my students save me. I can get mired in my own thoughts and it really helps to be drawn out, to stop ruminating and start reflecting. This past week we had some really interesting conversations about the death of Osama bin Laden, the memorialization of traumatic events, and reparations. Then I saw on Facebook that Sarah Park posted the reading list for her course on Social Justice in Children's/YA Literature. I've got so much reading to do! So this morning I woke up wanting to revisit the issue of equity in publishing. What would it look like? How can it be achieved? How do I, as an author, publish in a way that reflects my commitment to social justice?

Sometimes my students save me. I can get mired in my own thoughts and it really helps to be drawn out, to stop ruminating and start reflecting. This past week we had some really interesting conversations about the death of Osama bin Laden, the memorialization of traumatic events, and reparations. Then I saw on Facebook that Sarah Park posted the reading list for her course on Social Justice in Children's/YA Literature. I've got so much reading to do! So this morning I woke up wanting to revisit the issue of equity in publishing. What would it look like? How can it be achieved? How do I, as an author, publish in a way that reflects my commitment to social justice?

Remember my cousin's fabulous explanation of the difference between equity and diversity?

Diversity is when you invite many different kinds of people to sit at your table. You look for difference in terms of age, race, gender, sexuality, class, ability, ethnicity, etc. But equity means addressing the fact that some people come to the table without a fork, some have two plates or none at all, some expect to be waited on, and some are more accustomed to doing the serving. Equity attempts to ensure that everyone can sit down to eat together on terms of equality.

When I look at the publishing industry today, I see an approach that mirrors the diversity efforts on many college campuses. Debbie Reese posted this useful article ("The Invisible Campus Color Line") on Facebook a few weeks back and I shared it with my colleagues at work. There was some resistance, but at least half a dozen educators agreed that we're missing the mark when it comes to institutional equity:

Initially, schools are enthusiastic, pledging their full commitment to ensuring their campuses are free of racial, religious, and gender bias. They willingly participate in surveys that measure students' perceptions of cross-cultural relations on campus. They throw international dinners, sponsor diversity days, and spend weeks writing and refining diversity statements.

But when [EdChange founder Paul Gorski] begins to suggest the work that he believes really counts—reevaluating policies, reallocating budgets, and ultimately challenging the status quo—they stop returning his phone calls. They hire someone new, and they start again. Since student bodies turn over so quickly, it always looks as if the school is making an effort, even if they're actually just treading water.

I think it's safe to say that the publishing industry in the US is "just treading water" when it comes to diversity and equity. And as with college campuses, "Token efforts to 'celebrate diversity'…often amount to little more than marketing stunts." If the dominant group holds a huge banquet every year and after much petitioning finally invites three marginalized people to attend the banquet, that's not equity. If they say, "We love spicy food! Why don't you bring some of your delicious ethnic food for us to sample?" That's not equity. Getting invited might make you feel special, but whatever you bring to the table won't actually alter the power dynamics that determine who holds the banquet, determines the guest list, sets the menu, etc.

But what's actually achieved by NOT showing up at the banquet, or choosing to hold your own private party someplace else? If you show up at the banquet and try to tell the attendees about themselves, you'll be shunned and marginalized even further. If you show up, smile, and "go along to get along," then you're perpetuating the problem. You're upholding—and ultimately affirming—the status quo. Is that the price marginalized folks have to pay to get their books out into the world?

As far as I can tell, the only comprehensive plan to reform the publishing industry comes from the UK group, DIPNET.

The aim of the UK Publishing Equalities Charter is to help promote equality and diversity across UK publishing and bookselling, by driving forward change and increasing access to opportunities within the industry…

For many years the industry has spoken collectively of the need to make publishing more diverse yet has not embarked on an industry wide initiative to resolve this issue. "What is widely suspected about publishing has proven true: the industry remains an overwhelmingly white profession…"

That's true of the big houses and many small presses—even feminist and multicultural publishers. Amazon's expanding its publishing program, but will it transform or mirror the "all-white world" of traditional publishing? Self-publishing is one option, but there are obvious limitations to going it alone. DIPNET offers these steps to achieving equity in the publishing industry—can you see US publishers signing up for this?

SUGGESTED ACTIONS

Wherever possible try to recruit a representative mix of people according to your local demographics. For example 46% of England's ethnic minority population live in London (source: LDA: 'The Competitive Advantage of Diversity', Oct 2005), this should be reflected in organisations based in London.

Provide equality training for all staff on a yearly basis

Set up a staff equalities working group ensuring a good representation of people in the organisation

Create an equality policy that is embedded throughout the organisation in policy, strategy and working practice

Monitor the impact of policies through conducting equality impact assessments

Make all policies transparent by updating them and making them available to all staff (e.g. via the intranet)

Provide equality training for senior managers and board members

Make all job applicants complete an equality monitoring form which are monitored on a regular basis

Take on a trainee from an underrepresented group by hosting a Positive Action Traineeship

Increase recruitment pool by advertising jobs externally instead of informal recruitment methods (e.g. word of mouth)

Develop staff from underrepresented groups by providing training and career development opportunities

Develop a mentoring programme that supports new staff from traditionally underrepresented groups

Develop a mentoring programme that supports staff from traditionally underrepresented groups at transitional career stages

Hold an equality themed brown bag lunch for staff encouraging debate and dialogue amongst colleagues in an informal setting

Attract and recruit more disabled people to your organisation

Score all job applications on the core competencies required for the position to limit the use of informal recruitment methods

Make your sites accessible to all your clients and customers by conducting regular accessibility assessments

Include an equality statement within job advertisements

Ensure that all shortlisted candidates are asked whether they require any 'reasonable adjustments' prior to interview to ensure equal opportunities

Work towards achieving 'Two ticks positive about disabled people' accreditation which guarantees an interview to a candidate with a disability (as defined by the Disability Discrimination Act 2005) and who match the requirements of the person specification

Take part in careers events in order to raise the profile of the industry to traditionally underrepresented groups

Run an equality themed seminar at a book fair

Form a relationship with a local school and run workshops/talks to educate students about the industry

Conduct regular surveys to identify satisfaction levels amongst staff

Make available a cultural calendar for staff to raise awareness of cultural/religious dates throughout the year

Hold a 'Celebrating Equality' day to enable staff the opportunity to find out more about their colleagues in an interactive manner

Wherever possible ensure authentic representation of people from underrepresented groups (e.g. book cover designs, illustrations, marketing material etc.)

Be involved in industry wide collaborations to increase equality in publishing

Take part in yearly industry wide reporting through organisations such as Skillset

Take on flexible working/condensed working hours to support those with caring responsibilities

Bridge the gender gap by encouraging and training more women into management and senior management positions

Bridge the ethnicity gap by encouraging and training more people from diverse ethnic groups into management and senior management positions

Host an open day so that the general public can find out more about your organisation

Encourage members of staff to be involved in seminars/workshops/talks that raise the profile of the industry to traditionally underrepresented groups

Identify an Equalities champion on your board of trustees who can be responsible for monitoring action on equality

Last week a friend sent me this article about living an intellectual life outside of the academy; it's a little pie-in-the-sky, but at least someone's out there looking for alternatives. That's what's needed for the publishing industry…

May 5, 2011

great day!

We got some very good news yesterday: BIRD has won the West Virginia Children's Choice Award! Last year Diary of a Wimpy Kid won, so I'm really honored that the children found merit in our book. The competition is open to books published within the past three years that meet the literary standards adopted by the Children's Services Division of the American Library Association for Notable Books:

We got some very good news yesterday: BIRD has won the West Virginia Children's Choice Award! Last year Diary of a Wimpy Kid won, so I'm really honored that the children found merit in our book. The competition is open to books published within the past three years that meet the literary standards adopted by the Children's Services Division of the American Library Association for Notable Books:

Have high literary merit.

Have qualities of originality, imagination, and vitality.

Have an element of timelessness.

Reflect the sincerity of the author.

Have sound values.

Have a theme of subject worth imparting to and of interest to children.

Have factual accuracy.

Have clarity and readability.

Be appropriate in subject, treatment and format to the age group for which it is intended.

Then I looked on Amazon and noticed that a new review of WISH had been added. It's actually from a teacher who allowed her two students to post these evaluations of my novel:

Review 1: A Wish After Midnight by Zetta Elliot was an interesting book. It is about a girl, Genna, and how she is in a bad neighborhood and she wants out. She gets more than she bargained for when a wish sends her back to 1863. This book gives you a good look at some of the things that happened around the Civil War-era.

When Genna is in the world of 1863, she has to learn to fit in, work, not say what is on her mind, and find a way out. In the book, it shows you how everyone who was not white was treated.

This book has good information about the Civil War and a good story!

Review 2: A Wish After Midnight was an eye-opening book. Even though some parts in the beginning were a little intense, the historical part gives a great view on the start of the Civil War. The main character, Genna, shines a light on the difficulty of being a black girl in the 1800s while continuing to hope and work toward a positive and educated life for herself. This book has so many twists and turns that it keeps you on your toes as you await the next turn of events. A Wish After Midnight is a great segue into thinking about the Civil War because the number of perspectives you get from people with very different backgrounds and ideas. I would definitely recommend this book to anyone 13 or older who is looking for a book that really brings out the tensions and worries of people during the Civil War. From: Books R. Cool

May 3, 2011

mixed message

I've got a lot in my head these days, so let me start with the basics: there are some important events in the kidlit world that you definitely don't want to miss. Jodie and Colleen shared news of the annual GuysLitWire Book Fair, which enables you to donate books to a library in need. I love this initiative because the school has a say in the process—no one's dumping unwanted or unsold books onto these kids.

I've got a lot in my head these days, so let me start with the basics: there are some important events in the kidlit world that you definitely don't want to miss. Jodie and Colleen shared news of the annual GuysLitWire Book Fair, which enables you to donate books to a library in need. I love this initiative because the school has a say in the process—no one's dumping unwanted or unsold books onto these kids.

The next event was posted by Doret—the Diversity in YA book tour is coming to NYC! There will be two events in the city with authors Matt de la Peña, Malinda Lo, Kekla Magoon, Neesha Meminger, Cindy Pon, Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich, Rita Williams-Garcia, and Jacqueline Woodson. What a line-up!

Ok, here's where things get sketchy. I'm writing again, and that means I'm spending most of my time inside. Being productive on the inside often means that I'm cranky and/or blue on the outside. Not ideal when I still have to teach 3x a week and otherwise function in "the real world." Last weekend I wrote two thousand words about Nyla, a military brat who likes to call the shots but nonetheless finds herself the victim of sexual assault. On base. I've wanted to write about rape in the military for a while, but wasn't sure how the subject would manifest in my writing. I think I've figured it out—I've got this short piece about Nyla, and it concludes with her stepmother Sachi demanding the kind of justice many victims of sexual assault don't get in the military.

Then I woke up on Monday and learned that Osama bin Laden had been killed in a raid the night before. I looked at all the comments and quotes and links on Facebook and really couldn't think of what to say. I thought about the two classes I was scheduled to teach that afternoon and wondered how I could connect our course material to the breaking news. Then I checked my email inbox and found three photographs from a soldier I met online; I sent him some copies of Wish last year and he shared them with others stationed in Iraq. Ordinarily, I'd immediately post reader photos to my blog, but yesterday just didn't seem like the right day. And the more I looked at the photos—especially the one of a soldier holding up a copy of my book with a machine gun slung across his chest—the stranger it felt. What did I expect when I sent those books to Iraq? I wanted to "support the troops" and so I sent books and then Xmas decorations when the holidays rolled around. It felt like a sincere gesture, so why do I now have a problem posting those photos on my blog? You can't "support the troops" but only imagine them sipping egg nog in the mess hall. I can't post the "neutral" photos on my blog and withhold the image of the solider with the book AND the gun. So the photos are still sitting in my inbox.

Over the weekend I watched a movie about conscientious objectors to the war in Iraq; I listened to two soldiers (one active, one discharged) talk about hypocrisy. Are you a hypocrite if you insist on the right to object to war yet refuse to acknowledge that that right is defended by those willing to bear arms? The active soldier said, "What would have happened in WWII if soldiers hadn't taken up arms and fought the Nazis?" And the conscientious objector responded by saying, "What if more German soldiers had laid down their arms and refused to follow orders they knew were unjust?" The active soldier insisted there would never be enough conscientious objectors to end war; in this country we rely upon volunteers who are willing to risk their lives by joining the armed forces. Osama bin Laden is dead and that was brought about by highly trained Navy Seals. Would we need Navy Seals if there were no terrorists? It's a chicken & egg type of question. And the reality is, we can't ever get back to the moment/place where war wasn't necessary. When school girls have acid thrown on them in Afghanistan, I don't have a problem with US soldiers and guns. But when women soldiers are raped by fellow soldiers? I don't know what to do about the military. My older brother was in the reserves and I remember being so proud of him in his uniform. I never saw him with a gun. I never asked if he served alongside women. Now I have too many questions…

May 1, 2011

writing rape

I'm waiting for the latest proof of One Eye Open to arrive. During our self-publishing event in Toronto last month, someone asked us to break down the steps involved in publishing your own book. I tried to explain that the steps change with each book because you're accumulating more and more knowledge. They're now considering removing the proof option on Create Space, but I can't imagine why you'd want your book to go up for sale before you had a chance to look it over. At first I was excited about shooting my own photo for the book cover, but then found out my camera's automatically set to low-res so had to do it over on high-res. Fortunately, Cidra knew a professional photographer and Valerie ended up doing the shoot for me. Next I selected the photo, cropped it, boosted the color, and sent it to a photolab to be retouched. The lab technician's first question was, "Want me to make her lighter?" NO! The retouched photo came back a few days later and I think it's stunning, but still worried that the technician might have gone against my instructions. Representing women faithfully is really important to me. I've been writing this weekend and there's a new kind of anxiety stirring within: if I create a female character who's questioning her sexuality, is it a mistake to also make her a victim of sexual assault? I can recall all the times I've taught The Color Purple and had students insist that Celie was "turned into a lesbian" by the abuse she suffered at the hands of her stepfather. At the same time, I think it's important

I'm waiting for the latest proof of One Eye Open to arrive. During our self-publishing event in Toronto last month, someone asked us to break down the steps involved in publishing your own book. I tried to explain that the steps change with each book because you're accumulating more and more knowledge. They're now considering removing the proof option on Create Space, but I can't imagine why you'd want your book to go up for sale before you had a chance to look it over. At first I was excited about shooting my own photo for the book cover, but then found out my camera's automatically set to low-res so had to do it over on high-res. Fortunately, Cidra knew a professional photographer and Valerie ended up doing the shoot for me. Next I selected the photo, cropped it, boosted the color, and sent it to a photolab to be retouched. The lab technician's first question was, "Want me to make her lighter?" NO! The retouched photo came back a few days later and I think it's stunning, but still worried that the technician might have gone against my instructions. Representing women faithfully is really important to me. I've been writing this weekend and there's a new kind of anxiety stirring within: if I create a female character who's questioning her sexuality, is it a mistake to also make her a victim of sexual assault? I can recall all the times I've taught The Color Purple and had students insist that Celie was "turned into a lesbian" by the abuse she suffered at the hands of her stepfather. At the same time, I think it's important  to show that *all* children are vulnerable to abuse. In God Loves Hair, Vivek Shraya includes a disturbing but important scene where his child narrator is abused by a man while at an ashram. Although he's been warned about the man, the child—an aspiring religious devotee—sees in the adult the same loneliness and alienation he has experienced at school: "I look at him on the bed, sad and hunched over, like the last one to get picked for a team. I know that feeling. He is my brother, I tell myself." Unfortunately, the child's empathy leads to exploitation. His religious community is one place where the narrator feels accepted—even admired because of his exemplary singing during prayers. At school, it's an entirely different experience. Children who are bullied and/or isolated are made more vulnerable to abuse. Yet my character, Nyla, is something of a bully herself and is still victimized by an older teenage boy. The result is perhaps the same: Shraya's narrator and Nyla are both likely to be blamed for the abuse. You led him on, you went with him, you asked for it. I need to do some more research on this. In One Eye Open, the main character is a rape survivor who meets her best friend, Vinetta, in a support group for victims of sexual abuse. Nina's response to the rape is to shut herself off and avoid men entirely; Vinetta takes an opposite approach and engages in (sometimes risky) sexual behavior with women and men. Her bisexuality frightens Nina who can't imagine herself as a sexual being with the

to show that *all* children are vulnerable to abuse. In God Loves Hair, Vivek Shraya includes a disturbing but important scene where his child narrator is abused by a man while at an ashram. Although he's been warned about the man, the child—an aspiring religious devotee—sees in the adult the same loneliness and alienation he has experienced at school: "I look at him on the bed, sad and hunched over, like the last one to get picked for a team. I know that feeling. He is my brother, I tell myself." Unfortunately, the child's empathy leads to exploitation. His religious community is one place where the narrator feels accepted—even admired because of his exemplary singing during prayers. At school, it's an entirely different experience. Children who are bullied and/or isolated are made more vulnerable to abuse. Yet my character, Nyla, is something of a bully herself and is still victimized by an older teenage boy. The result is perhaps the same: Shraya's narrator and Nyla are both likely to be blamed for the abuse. You led him on, you went with him, you asked for it. I need to do some more research on this. In One Eye Open, the main character is a rape survivor who meets her best friend, Vinetta, in a support group for victims of sexual abuse. Nina's response to the rape is to shut herself off and avoid men entirely; Vinetta takes an opposite approach and engages in (sometimes risky) sexual behavior with women and men. Her bisexuality frightens Nina who can't imagine herself as a sexual being with the  right to make a wide range of choices; she's trying to play it safe but that only binds Nina to the past. In my class we talk about Toni Morrison's definition of freedom: "choice without stigma." For Yvette Christianse, freedom is "not having fear." We're reading Unconfessed this week, which is a fictional narrative of an enslaved woman jailed on Robben Island for taking the life of her enslaved son. Imprisoned in several jails, Sila is raped repeatedly by guards and yet offers very few details, choosing to focus instead on the children conceived through rape. Sila won't be defined as a beast, a drunkard, a murderer. She is a mother, a friend, a daughter and she clings to the memories that reinforce these identities. But she can't shut out the vuilgoed, the filth. Sometimes teaching this material helps my own writing, but sometimes it wears me OUT.

right to make a wide range of choices; she's trying to play it safe but that only binds Nina to the past. In my class we talk about Toni Morrison's definition of freedom: "choice without stigma." For Yvette Christianse, freedom is "not having fear." We're reading Unconfessed this week, which is a fictional narrative of an enslaved woman jailed on Robben Island for taking the life of her enslaved son. Imprisoned in several jails, Sila is raped repeatedly by guards and yet offers very few details, choosing to focus instead on the children conceived through rape. Sila won't be defined as a beast, a drunkard, a murderer. She is a mother, a friend, a daughter and she clings to the memories that reinforce these identities. But she can't shut out the vuilgoed, the filth. Sometimes teaching this material helps my own writing, but sometimes it wears me OUT.