writing rape

I'm waiting for the latest proof of One Eye Open to arrive. During our self-publishing event in Toronto last month, someone asked us to break down the steps involved in publishing your own book. I tried to explain that the steps change with each book because you're accumulating more and more knowledge. They're now considering removing the proof option on Create Space, but I can't imagine why you'd want your book to go up for sale before you had a chance to look it over. At first I was excited about shooting my own photo for the book cover, but then found out my camera's automatically set to low-res so had to do it over on high-res. Fortunately, Cidra knew a professional photographer and Valerie ended up doing the shoot for me. Next I selected the photo, cropped it, boosted the color, and sent it to a photolab to be retouched. The lab technician's first question was, "Want me to make her lighter?" NO! The retouched photo came back a few days later and I think it's stunning, but still worried that the technician might have gone against my instructions. Representing women faithfully is really important to me. I've been writing this weekend and there's a new kind of anxiety stirring within: if I create a female character who's questioning her sexuality, is it a mistake to also make her a victim of sexual assault? I can recall all the times I've taught The Color Purple and had students insist that Celie was "turned into a lesbian" by the abuse she suffered at the hands of her stepfather. At the same time, I think it's important

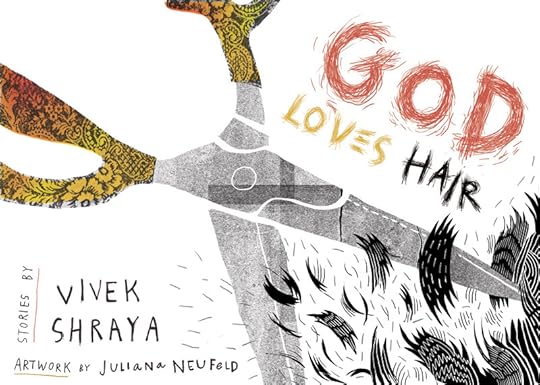

I'm waiting for the latest proof of One Eye Open to arrive. During our self-publishing event in Toronto last month, someone asked us to break down the steps involved in publishing your own book. I tried to explain that the steps change with each book because you're accumulating more and more knowledge. They're now considering removing the proof option on Create Space, but I can't imagine why you'd want your book to go up for sale before you had a chance to look it over. At first I was excited about shooting my own photo for the book cover, but then found out my camera's automatically set to low-res so had to do it over on high-res. Fortunately, Cidra knew a professional photographer and Valerie ended up doing the shoot for me. Next I selected the photo, cropped it, boosted the color, and sent it to a photolab to be retouched. The lab technician's first question was, "Want me to make her lighter?" NO! The retouched photo came back a few days later and I think it's stunning, but still worried that the technician might have gone against my instructions. Representing women faithfully is really important to me. I've been writing this weekend and there's a new kind of anxiety stirring within: if I create a female character who's questioning her sexuality, is it a mistake to also make her a victim of sexual assault? I can recall all the times I've taught The Color Purple and had students insist that Celie was "turned into a lesbian" by the abuse she suffered at the hands of her stepfather. At the same time, I think it's important  to show that *all* children are vulnerable to abuse. In God Loves Hair, Vivek Shraya includes a disturbing but important scene where his child narrator is abused by a man while at an ashram. Although he's been warned about the man, the child—an aspiring religious devotee—sees in the adult the same loneliness and alienation he has experienced at school: "I look at him on the bed, sad and hunched over, like the last one to get picked for a team. I know that feeling. He is my brother, I tell myself." Unfortunately, the child's empathy leads to exploitation. His religious community is one place where the narrator feels accepted—even admired because of his exemplary singing during prayers. At school, it's an entirely different experience. Children who are bullied and/or isolated are made more vulnerable to abuse. Yet my character, Nyla, is something of a bully herself and is still victimized by an older teenage boy. The result is perhaps the same: Shraya's narrator and Nyla are both likely to be blamed for the abuse. You led him on, you went with him, you asked for it. I need to do some more research on this. In One Eye Open, the main character is a rape survivor who meets her best friend, Vinetta, in a support group for victims of sexual abuse. Nina's response to the rape is to shut herself off and avoid men entirely; Vinetta takes an opposite approach and engages in (sometimes risky) sexual behavior with women and men. Her bisexuality frightens Nina who can't imagine herself as a sexual being with the

to show that *all* children are vulnerable to abuse. In God Loves Hair, Vivek Shraya includes a disturbing but important scene where his child narrator is abused by a man while at an ashram. Although he's been warned about the man, the child—an aspiring religious devotee—sees in the adult the same loneliness and alienation he has experienced at school: "I look at him on the bed, sad and hunched over, like the last one to get picked for a team. I know that feeling. He is my brother, I tell myself." Unfortunately, the child's empathy leads to exploitation. His religious community is one place where the narrator feels accepted—even admired because of his exemplary singing during prayers. At school, it's an entirely different experience. Children who are bullied and/or isolated are made more vulnerable to abuse. Yet my character, Nyla, is something of a bully herself and is still victimized by an older teenage boy. The result is perhaps the same: Shraya's narrator and Nyla are both likely to be blamed for the abuse. You led him on, you went with him, you asked for it. I need to do some more research on this. In One Eye Open, the main character is a rape survivor who meets her best friend, Vinetta, in a support group for victims of sexual abuse. Nina's response to the rape is to shut herself off and avoid men entirely; Vinetta takes an opposite approach and engages in (sometimes risky) sexual behavior with women and men. Her bisexuality frightens Nina who can't imagine herself as a sexual being with the  right to make a wide range of choices; she's trying to play it safe but that only binds Nina to the past. In my class we talk about Toni Morrison's definition of freedom: "choice without stigma." For Yvette Christianse, freedom is "not having fear." We're reading Unconfessed this week, which is a fictional narrative of an enslaved woman jailed on Robben Island for taking the life of her enslaved son. Imprisoned in several jails, Sila is raped repeatedly by guards and yet offers very few details, choosing to focus instead on the children conceived through rape. Sila won't be defined as a beast, a drunkard, a murderer. She is a mother, a friend, a daughter and she clings to the memories that reinforce these identities. But she can't shut out the vuilgoed, the filth. Sometimes teaching this material helps my own writing, but sometimes it wears me OUT.

right to make a wide range of choices; she's trying to play it safe but that only binds Nina to the past. In my class we talk about Toni Morrison's definition of freedom: "choice without stigma." For Yvette Christianse, freedom is "not having fear." We're reading Unconfessed this week, which is a fictional narrative of an enslaved woman jailed on Robben Island for taking the life of her enslaved son. Imprisoned in several jails, Sila is raped repeatedly by guards and yet offers very few details, choosing to focus instead on the children conceived through rape. Sila won't be defined as a beast, a drunkard, a murderer. She is a mother, a friend, a daughter and she clings to the memories that reinforce these identities. But she can't shut out the vuilgoed, the filth. Sometimes teaching this material helps my own writing, but sometimes it wears me OUT.