Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 87

July 10, 2011

pink icing

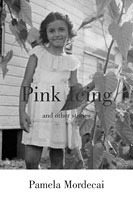

On two occasions when I've been talking about my search for contemporary depictions of black teens IN Canada, Pamela Mordecai's book, Pink Icing, has come up. And twice I resisted adding the title to my study–after all, it's not a novel and from the description I read online, it's not a MG or YA book. "No, no," I was told at the ChLA conference, "It's written for kids and talks about Canada." So I ordered it and read it yesterday; I'm not a fan of short stories and really had to push myself to finish—not because the writing wasn't strong or compelling, it was—but I had to know why Pink Icing kept coming up. It's a collection of twelve short stories and NOT ONE is set in contemporary Canada; one white priest hails from Ontario and one drug-dealing Jamaican man apparently flies back and forth to Toronto, but all of the stories take place in the Caribbean. Here's the publisher's description:

On two occasions when I've been talking about my search for contemporary depictions of black teens IN Canada, Pamela Mordecai's book, Pink Icing, has come up. And twice I resisted adding the title to my study–after all, it's not a novel and from the description I read online, it's not a MG or YA book. "No, no," I was told at the ChLA conference, "It's written for kids and talks about Canada." So I ordered it and read it yesterday; I'm not a fan of short stories and really had to push myself to finish—not because the writing wasn't strong or compelling, it was—but I had to know why Pink Icing kept coming up. It's a collection of twelve short stories and NOT ONE is set in contemporary Canada; one white priest hails from Ontario and one drug-dealing Jamaican man apparently flies back and forth to Toronto, but all of the stories take place in the Caribbean. Here's the publisher's description:

Telling stories of ordinary lives with extraordinary skill, Pamela Mordecai draws delicately detailed portraits of life in Jamaica and other islands, with occasional trips to Canada. Her characters speak with the cadences of the Caribbean, and cope with the universal experiences of birth and death, joy and betrayal.

In "Hartstone High," a group of girls learn the high price of education; in "Alvin's Ilk," a self-centred teenaged boy comes to see his elderly neighbour in a whole new way; and in "Shining Waters," a young priest's plans for his new parish go horribly awry.

Mordecai turns a sharp ear to the nuances of everyday speech, exposing the currents beneath the calm exterior and producing complex tales that will challenge and entertain her readers.

More than half of the stories have child protagonists, but this is not, I would argue, a YA book. It could easily be taught to high school students, and I'd love to see it added to the school curriculum in Canada, but I don't see anything indicating that the book was intended for the kidlit market (nothing on the publisher's website, nothing on its Amazon page, where age range and reading level are usually provided). In 2008, the author described her audience this way:

…it's with much delight that I discovered today that it's on amazon.ca's list of the top 100 titles in the category "African-American Studies"! (It may well not stay there, but it is there as of now!) I'm hoping that means it's got onto courses in high school, college, and university. That's not just because it will mean improved book sales, though I won't deny this is important since I earn my living exclusively from writing. It's because I think it's a book anyone can enjoy, in particular anyone from the Caribbean.

Pamela Mordecai is married to Martin Mordecai, author of Blue Mountain Trouble—a novel clearly intended for children that is also set in Jamaica. I'd love to know how either of these books resonates with black children born in Canada to immigrant parents from the Caribbean. And just to be clear—I have no problem with books for (or about) children that are set outside of Canada; I'm just explaining why this particular book isn't included in my study of MG/YA novels published in Canada.

July 5, 2011

bad blood

I've written three thousand words over the past couple of days. Funny how everything comes all at once. I saw a scene unfold while I was on the train a couple of weeks ago, but never bothered to write it down. Then I read a gentle, quiet book and by the time I was done, all these angry, violent scenes started to flow. Nyla's a character from Ship of Souls; her mother abandoned her as a child so she was raised by her African American father and Japanese American stepmother on a military base in Germany. In this new book, I'm building off a line I heard upon waking up one morning last spring: "Are you sure you're fully human?"

"What kind of mother just walks out on her kid?"

"You had Cal—and he had his mother." Graciela screws up her lips but thinks better of disrespecting the dead. "Besides, it's not like you were a baby or anything. I waited until you were grown."

"Grown?! I was four."

"You've always been mature for your age. I knew you could handle yourself. You could walk, talk, flush—you didn't need me anymore." She wavers then pushes herself on. "Plus…you didn't show any signs. You were clean then. I couldn't—I couldn't risk you…picking anything up from prolonged exposure to me."

"This shit's contagious?"

Graciela shakes her head. "Genetic, apparently. But I didn't know then what I know now. I was trying to do the right thing. And I'm trying to do that now. So listen to me, ok? Just…lay low for a while. And whatever you do—stay above ground."

"That's it? Avoid the subway? That's the best you can do? Something tried to kill me—and my friends."

"Which is why you need to stay the hell away from them, too. I'll speak to your father—now's a good time for a little family vacation, I think."

"Are you planning to join us?"

"You really don't get it, do you? I'm trying to keep you safe—and that means staying as far away from me as possible."

"They're after you, too?"

Graciela sighs impatiently and tries not to lose her cool. "No, Nyla. They're not after me. I'm after them."

I stare at my mother without blinking as an image forms in my mind. "You mean you're—like, a slayer?"

"God—everything's a TV show or a comic book to you! I'm not a vampire slayer and I'm not a mutant—and neither are you."

"What are you, then?" Graciela turns and takes a few steps away from me. "And what am I?"

Sequel's aren't easy. This summer was supposed to be my time to finish the sequel to Wish, and instead I've started a sequel to Ship of Souls, which hasn't even been published yet. I'm getting ahead of myself. I have a short story to work on, an interview, and a guest post for another blog. But it's hard to stop the story once it starts coming. This is the last scene I worked on last night:

"You on the Pill?"

"What?"

"Birth control—you know what that is, right?"

"Of course, I do! Not that it's any of your business…"

"That's my blood in your veins—I'm making it my business."

"I'm not sexually active, alright?"

Graciela finds Keem lingering over by the window. "You will be soon, the way that boy keeps looking at you."

"He doesn't decide that—I do."

Graciela looks at me with something close to admiration. "I'm glad to hear that." She watches me a moment longer and then asks quietly, "You learn that the hard way?"

I hesitate, then nod and avoid her eyes.

"Did Cal make the kid pay for it?"

I look at my mother. "I did. I split his head open."

Again Graciela looks at me with a strange kind of pride. She reaches out a hand and flicks my bangs out of my eyes. "That why you went punk? To scare the boys away? Your father must have had a heart attack when you cut your hair. He was always so proud of his little princess."

"I couldn't be daddy's little girl forever. Besides, he's supposed to love me no matter what."

"Love's never unconditional. There are always strings attached."

"Is that what I was—a string that tied you down?"

Graciela says nothing for a moment. "I thought that if I mixed my blood with your father's—I could dilute it. I thought it would be ok." Graciela tries to laugh but can't. "And look at you now."

"You wish I'd never been born."

Graciela ends my pity party before it can even begin. "I never said that!" She glares at me for a long moment before letting go of my wrist. "I just want you to think things through. If Marta's right and your power really is off the charts…then you can't afford to reproduce."

"Why not? What if that's the answer—making more and more soldiers for the cause. We could build our own army and end it once and for all."

Graciela makes a sound of contempt. "You sound like your father."

"I'm just saying there's strength in numbers. You don't have to do everything all by yourself."

"Oh yeah? Well, before you start popping out superbabies think about how you'd feel watching one of your kids die before your eyes. Because it happens, Nyla. It almost happened to me today."

I stare at the cold food on my plate and quietly admit, "I wasn't sure you were going to save me."

"I wasn't sure I'd be able to. I had to send G**** back into the depths. I just hoped I could banish him and still hold onto you."

"You hoped?"

Graciela just shrugs and avoids looking at me. "Think about what I said. I'm sure your stepmother could help you get on the Pill without Cal finding out."

Finally our eyes meet and for just a moment I see the woman my mother used to be. The woman she was before she became a hardened warrior. "If I'd stayed longer, I only would have loved you more. Understand?"

Before I can answer, Graciela walks away and slams her entire tray into the trash.

July 1, 2011

tgif

This week has been *challenging*! Melanie Hope Greenberg, who reads tarot cards when she's not illustrating picture books, explains that today is a new moon eclipse, which can create some instability. I was really looking forward to interviewing Jacqueline Woodson today, and since I'm an anxiety freak, I made sure I had everything prepared in advance—I charged my Flip camera, brought my digital camera to take some stills, and had my questions all typed up. Got to her lovely home and within FIVE MINUTES the Flip died. Even though it said I had 2 hours worth of memory space. Grrr…I tried filming with my digital camera, but had never done that before and worried it, too, would die after five or ten minutes. Jackie was her usual gracious self, and agreed to reschedule before sending me home with new books to read. Of course, I plugged my Flip in as soon as I got home and decided to make a short film just to be sure the camera works. UPS delivered three packages from my uncle in Winnipeg containing family heirlooms—I won't bore you with the footage of me tearing open the boxes, but this is a still of my great-great-aunt's painting; she studied at an art academy as a young woman and this painting used to hang in my grandparent's house. I remember the swans…I'm assuming she "passed" for white while in Toronto; no one would have known she was a Negro woman, and had she been brown-skinned, she likely would have been barred from the school. Now have photos of her painting at her easel, and a beautiful portrait taken in a professional studio. Will try to regroup this weekend so I'm ready for whatever's in the stars for next week…

This week has been *challenging*! Melanie Hope Greenberg, who reads tarot cards when she's not illustrating picture books, explains that today is a new moon eclipse, which can create some instability. I was really looking forward to interviewing Jacqueline Woodson today, and since I'm an anxiety freak, I made sure I had everything prepared in advance—I charged my Flip camera, brought my digital camera to take some stills, and had my questions all typed up. Got to her lovely home and within FIVE MINUTES the Flip died. Even though it said I had 2 hours worth of memory space. Grrr…I tried filming with my digital camera, but had never done that before and worried it, too, would die after five or ten minutes. Jackie was her usual gracious self, and agreed to reschedule before sending me home with new books to read. Of course, I plugged my Flip in as soon as I got home and decided to make a short film just to be sure the camera works. UPS delivered three packages from my uncle in Winnipeg containing family heirlooms—I won't bore you with the footage of me tearing open the boxes, but this is a still of my great-great-aunt's painting; she studied at an art academy as a young woman and this painting used to hang in my grandparent's house. I remember the swans…I'm assuming she "passed" for white while in Toronto; no one would have known she was a Negro woman, and had she been brown-skinned, she likely would have been barred from the school. Now have photos of her painting at her easel, and a beautiful portrait taken in a professional studio. Will try to regroup this weekend so I'm ready for whatever's in the stars for next week…

June 29, 2011

it does a heart good…

…to discover new allies. I've been enjoying the posts over at Amy Reads—my last paper addressed the different understanding of multiculturalism in Canada and the US, and I concluded that Canadians suffer from an unwarranted superiority complex when it comes to recognizing and respecting difference. I often find that when I raise the issue of inequity, Canadians (and not only whites) insist that I'm "obsessed" with race and simply imagining things. So it's refreshing to meet a blogger who's not afraid to grapple with these issues AND is thoughtful enough to offer solutions:

…to discover new allies. I've been enjoying the posts over at Amy Reads—my last paper addressed the different understanding of multiculturalism in Canada and the US, and I concluded that Canadians suffer from an unwarranted superiority complex when it comes to recognizing and respecting difference. I often find that when I raise the issue of inequity, Canadians (and not only whites) insist that I'm "obsessed" with race and simply imagining things. So it's refreshing to meet a blogger who's not afraid to grapple with these issues AND is thoughtful enough to offer solutions:

Wondering what you can do? I've pulled together a short list of suggestions, please add more in comments!

Find books that are coming out by authors of color or who are gay, as well as books featuring characters of color and of varying gender and sexual persuasions, and request a review copy. If we show that we are interested in them, the industry might listen.

If you focus on young adult literature, join the Diversity in YA Challenge hosted by Malinda Lo and Cindy Pon.

Read Zetta Elliott's post and help out in any way you can to make equity in publishing a priority in North America.

Pick at least one other country a month and try to learn more about it online and also learn something about authors from there. Read one or two if you can. As citizens of the world we should be informed about issues around the world. Knowing about other cultures shouldn't be a luxury it should be a requirement. Let's make it cool to learn more about those global voices!

Think about and discuss diversity in publishing and reading and realize why it is important.

And speaking of allies, I've been meaning to write about the ChLA conference for some time now but as soon as I got back from Roanoke I had to prepare for an interview in Atlanta. I have another interview next week and so I've been thinking a lot about the academy, its pros and cons. There was a moment in Roanoke when I felt like I was in the company of kindred spirits—and that doesn't often happen in my professional environments, which is probably why I generally keep a low profile. Back in May I considered pulling out of the conference; it was a considerable expense and I'm not really a children's literature scholar. I suspected I'd show up and spend the day alone, feeling very much on the outside of things. But the exact opposite was true: as soon as I arrived at the airport, I met two graduate students who had come from California and were trained by my co-panelist, June Cummins. We shared a cab and talked about the job market and the need to professionalize early on, to get out into the field, attending and presenting at conferences, publishing and networking with other scholars. I never did any of that as a graduate student because I never truly believed I'd enter the academy. Now I'm more committed to an academic life, but can't find a school that values both my creative writing and "nontraditional" scholarship. But as I delivered my paper on Thursday morning and felt the positive energy from the audience, I realized that it *is* possible to be who I am in the academy. My fellow panelists, June and Uma Krishnaswami (Abbie Ventura was unable to attend so her paper was read aloud), presented fabulous papers that were also warmly received by the audience. Our panel co-Chairs, Sarah Park and Thomas Crisp, were welcoming and organized and facilitated a good discussion afterward. Then they shifted seats and read their own amazing papers for the panel, "Sliding Doors in a Pluralistic Society: Reframing Images of America and Inclusion." I should have taken notes but I was so absorbed in their papers! Sarah presented on "Mis/Understanding the 'Angry' Adoptee"—for once, someone was talking seriously about RAGE and the ways in which marginalized and/or mistreated people are too often dismissed as "hysterical" or "irrational" when they challenge dominant practices or perceptions. I have a close friend who's a transracial adoptee, and through her have done some reading on the subject; it's unreal how she's expected to always be happy and grateful for her adoption, how she's expected to put the feelings of her adoptive and biological parents ahead of her own…Sarah then read Debbie Reese's part (ETA: Debbie was in New Orleans at ALA) of a dialogue with Thomas about "Identity, Representation, and Cultural Change Across Fields and Genre." As scholars in American Indian Studies and Queer Theory, Debbie and Thomas reflected on the moments when they felt alienated and accepted by other professionals, and their decision to become allies in the fight for social justice. What do you do when you're trying to create change—when it's a matter of life or death—and those around you refuse to be moved? The conversation following that panel (which also included Anna L. Nielsen's presentation on the representation of the Muslim experience) was also engaging and when it ended, I felt as though I'd found even more allies—I met Michelle Martin, the first black president of ChLA, and Jeffrey Canton, a Canadian scholar who boldly asked, "Why aren't we talking about the role publishers play in all this?" I had lunch with Sarah, talked more with Jeffery and Michelle and Lissa Paul, and met other folks who said they'd really enjoyed my presentation. I was only at the conference for half a day, but I left feeling it had been totally worthwhile. Will I ever find an academic job where I can feel as accepted and validated? I don't know. But conferences don't just advance your career—they connect you to a community of allies, which is what matters most.

June 28, 2011

seeing stars

I have to begin with this beautiful trailer for Navjot Kaur's latest book, Dreams of Hope:

Yes, there's a place for books like Go the F*** to Sleep (though I don't really appreciate a black father—Samuel Jackson—being used to voice the supposedly unspeakable thoughts of parents everywhere), but this lovely book is how you want to send your little one off to dreamland. Please do support this indie press! A while back we discussed the possibility of starting a Birthday Party Project—a campaign to get parents to commit to buying multicultural books as presents for any occasion, but specifically for the endless stream of birthday parties that most kids attend every year. Having books in the home and developing the habit of leisure reading impact a child's academic success—and studies show that black and Latino kids have fewer books at home and read less during leisure time:

One of the things often overlooked in discussions of academic achievement is the importance of leisure reading, not only the quality of it but the volume of it. There are, in fact, solid correlations between how much reading teens do on their own and how well they perform in school…

When we look at the results broken down by race, more concerns arise. Table 11 doesn't separate racial groups into age groups, but the racial groups in general show marked differences that likely are reproduced for the teen category alone. Whites come in at .31 and .37 hours on weekdays and weekend days, respectively. Blacks come in at half that figure, .17 and .18, even though blacks have more leisure time than whites (5.61 hours to 5.14 hours per day). Hispanics have less leisure time (4.89 hours) and pile up even less leisure reading (.15 and .11 hours on weekdays and weekend days).

Edi's got a list of new releases if you're putting together a summer reading list for the teen in your life. And there are lots of great books that didn't get their fair share of the spotlight last year—be sure to check out Nerds Heart YA. You can also find author interviews at Reading in Color, The Rejectionist, and The Happy Nappy Bookseller. And while you're there, check out Doret's great list of LGBTQ novels featuring queer teens of color.

I went to the PEN American Center office today and met with Stacey Leigh—she told me all about the Open Book Program:

Initiated in 1991, the PEN Open Book Program encourages racial and ethnic diversity within the literary and publishing communities. Its committee works to increase the literature by, for, and about African, Arab, Asian, Caribbean, Latin, and Native Americans, and to establish access for these groups to the publishing industry. Its goal is to insure that those who are the custodians of language and literature are representative of the American people.

The Open Book Committee includes writers and publishing industry professionals from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. The Committee discusses mutual concerns and strategies for advancing writing and professional activities, and coordinates Open Book events.

We're hoping to host a mixer later this month to give people a chance to meet and have their say about topics related to publishing. I'm excited about the possibilities and will post more in the near future, so stay tuned!

June 24, 2011

The Bottom of the Pot ~ ChLA

I've got a long post to write about my first Children's Literature Association conference but I got home at 2am last night and need a day of rest (and silence–even in my head). So for now, I've decided to post my conference paper; not sure I'll develop this for publication, but figured it couldn't hurt to make it available on the blog.

"The Bottom of the Pot: Blackness and Be/longing in A Wish After Midnight"

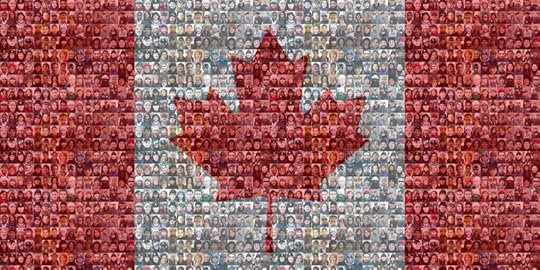

I am an immigrant. I was born in Canada, which means that I grew up "resisting Americanization;" in school I was taught to embrace the "tossed salad" metaphor rather than the "melting pot"—Canada was presented as a multicultural "mosaic," a nation where all kinds of differences were not only celebrated but protected. Canadians often define themselves in opposition to Americans; they pride themselves on being quiet, polite, and progressive—the antithesis of their loud, boorish, bigoted neighbors. I learned at an early age to look down my nose at the United States; it's something of a national pastime and a legacy of Canada's colonial past. Of course, it didn't help that my father used to slip across the border whenever life in "the Great White North" became unbearable. He would eventually return, bearing wondrous gifts (like a black Barbie doll) and for months we'd have to listen to him rhapsodizing about the US. As an adolescent, I disdained the United States yet still elected to study American History in high school, perhaps as a way of connecting with my father. I could not deny that the US had a certain allure—all the pop stars and television shows I admired were American—but I also understood that a fascination with "that country" could and would disrupt my life.

I am an immigrant. I was born in Canada, which means that I grew up "resisting Americanization;" in school I was taught to embrace the "tossed salad" metaphor rather than the "melting pot"—Canada was presented as a multicultural "mosaic," a nation where all kinds of differences were not only celebrated but protected. Canadians often define themselves in opposition to Americans; they pride themselves on being quiet, polite, and progressive—the antithesis of their loud, boorish, bigoted neighbors. I learned at an early age to look down my nose at the United States; it's something of a national pastime and a legacy of Canada's colonial past. Of course, it didn't help that my father used to slip across the border whenever life in "the Great White North" became unbearable. He would eventually return, bearing wondrous gifts (like a black Barbie doll) and for months we'd have to listen to him rhapsodizing about the US. As an adolescent, I disdained the United States yet still elected to study American History in high school, perhaps as a way of connecting with my father. I could not deny that the US had a certain allure—all the pop stars and television shows I admired were American—but I also understood that a fascination with "that country" could and would disrupt my life.

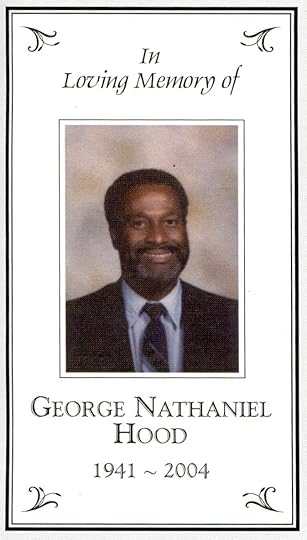

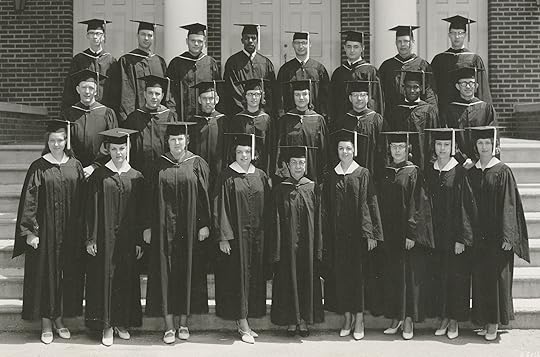

Although he came to Canada from the Caribbean as a teenager, my father spoke without an accent and felt perfectly at ease around whites. I never wondered why. Indeed, I grew up thinking of my father as a "generic" black man with no fixed ethnicity, and I was myself a young adult before I understood how the United States had shaped his identity—and mine. When my father arrived in Toronto at age 15, his stepmother indicated that he was not welcome in her home. Desperate to keep the peace, my grandfather tried to enlist my father in the army, but when that scheme failed, my great-aunt instead enrolled my father in a Christian high school—in Allentown, PA. Her conservative church handled everything; my father was sent to the United States where he finished high school and then entered Eastern Pilgrim Bible College. He was one of only two black male students on campus and in the spirit of Christian fellowship, was strictly forbidden from dating the white co-eds.

Although he came to Canada from the Caribbean as a teenager, my father spoke without an accent and felt perfectly at ease around whites. I never wondered why. Indeed, I grew up thinking of my father as a "generic" black man with no fixed ethnicity, and I was myself a young adult before I understood how the United States had shaped his identity—and mine. When my father arrived in Toronto at age 15, his stepmother indicated that he was not welcome in her home. Desperate to keep the peace, my grandfather tried to enlist my father in the army, but when that scheme failed, my great-aunt instead enrolled my father in a Christian high school—in Allentown, PA. Her conservative church handled everything; my father was sent to the United States where he finished high school and then entered Eastern Pilgrim Bible College. He was one of only two black male students on campus and in the spirit of Christian fellowship, was strictly forbidden from dating the white co-eds.

My father returned to Canada after graduation and married my mother—the white daughter of a United Church minister. Despite being groomed for the ministry, my father chose to teach rather than preach. He ran for public office—and lost. He tried to add a Black Heritage component to the Toronto public school curriculum—and failed. He had an affair with a black woman he once knew back in Allentown—and my mother divorced him. My father grew out his Afro and became something of a black militant. But there wasn't much tolerance for militancy in Toronto in 1980. Within a few years, my father settled down, started a new family, and learned to accept the status quo. Or so I thought.

My father returned to Canada after graduation and married my mother—the white daughter of a United Church minister. Despite being groomed for the ministry, my father chose to teach rather than preach. He ran for public office—and lost. He tried to add a Black Heritage component to the Toronto public school curriculum—and failed. He had an affair with a black woman he once knew back in Allentown—and my mother divorced him. My father grew out his Afro and became something of a black militant. But there wasn't much tolerance for militancy in Toronto in 1980. Within a few years, my father settled down, started a new family, and learned to accept the status quo. Or so I thought.

The year before I graduated from high school, my father disappeared. We all knew he'd gone to the United States again and we all assumed he'd eventually return. We were wrong. I started college in Quebec and received a letter from my father telling me he was now remarried and living in Brooklyn, NY. Not yet certified to teach there, he drove a gypsy cab along the bus route and would occasionally send me three or four crumpled dollar bills. When I graduated from college, my father invited me to spend the summer with him in Brooklyn and before long I moved all my belongings across the border. His stated goal was to have all four of his children living in the United States. But my father died of cancer in 2004, and I am the only one of my siblings who chose to pursue my own "American Dream."

I begin with this summary of my father's life because I see evidence in his narrative of the many forces that operate upon the immigrant generally and upon the black immigrant to (North) America specifically—forces which shaped my own life story and my young adult novel, A Wish After Midnight. My father used to complain that he "couldn't get anything started" in Canada. The United States, by contrast, stuck in his memory as the land of opportunity where a hard-working black man of humble origin could aspire to almost anything despite the pressure he once felt in the 1960s to lose his Caribbean accent, keep to his side of the color line, and not join the Civil Rights Movement. Though my father cautioned me against a life as a writer (and wished I had chosen a practical profession like law rather than academia), it is as a storyteller and scholar that I have learned to detect, embrace—and mount my own resistance against—the processes of Americanization.

I begin with this summary of my father's life because I see evidence in his narrative of the many forces that operate upon the immigrant generally and upon the black immigrant to (North) America specifically—forces which shaped my own life story and my young adult novel, A Wish After Midnight. My father used to complain that he "couldn't get anything started" in Canada. The United States, by contrast, stuck in his memory as the land of opportunity where a hard-working black man of humble origin could aspire to almost anything despite the pressure he once felt in the 1960s to lose his Caribbean accent, keep to his side of the color line, and not join the Civil Rights Movement. Though my father cautioned me against a life as a writer (and wished I had chosen a practical profession like law rather than academia), it is as a storyteller and scholar that I have learned to detect, embrace—and mount my own resistance against—the processes of Americanization.

A recent article published in The Journal of Research on Libraries and Young Adults affirms that "…studies have consistently found that minority-race characters are underrepresented in fiction for children and young adults, and that existing portrayals of minority characters are often riddled with stereotypes or otherwise negative images." The author further asserts, however, that "Studies addressing nationality of authors or characters are less common."[i]

This paper will address my competing nationalities and those of my fictional characters. Many immigrants experience a degree of ambivalence when it comes to assimilation; the allure of a new life/identity is tempered by the desire/duty to honor one's heritage. For black immigrants, that ambivalence can slide into cynicism (and even rage) when it becomes clear that every black person in the US is subject to a pernicious sort of reduction: we all "fit the profile" despite our varying ethnicities, class locations, and/or places of origin. Black immigrants, therefore, experience pressure to become American and additional pressure to suppress ethnic/cultural/political differences in order to conform to a "generic" domestic blackness—a kind of "African Americanization." For the purpose of this paper, I will use "Americanization" to refer to pressure to assimilate certain "representative" US values and to perform the role assigned by the dominant group.

As a child in Canada I vividly remember watching American cartoons on Saturday morning; this meant that, like millions of US children, I learned about American culture, history, and government through the Schoolhouse Rock series. On the issue of immigration, Schoolhouse Rock set to music the widely accepted narrative of "The Great American Melting Pot" (click on image for video) where immigrants from (mostly white European) countries willingly jump into a literal pot filled with others happily frolicking in the red, white, and blue "stew." Not surprisingly, no mention is made of the trans-Atlantic slave trade that supplied the forced labor that built the new nation; the catchy song rightly predicts that "any kid could be the president" but falsely claims that "You simply melt right in, it doesn't matter what your skin."[ii] Scholars in the field of Whiteness Studies have demonstrated how assimilation, over time, diminished ethnic and religious differences that once led to the persecution of groups like the

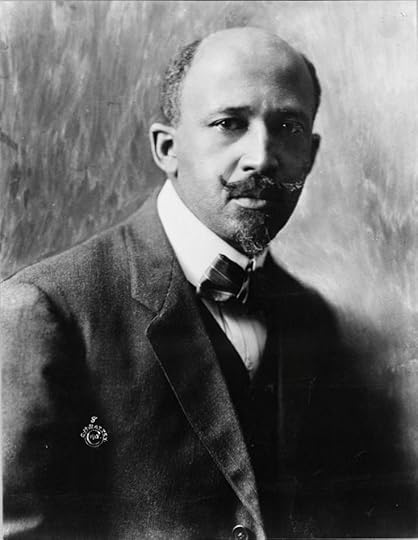

As a child in Canada I vividly remember watching American cartoons on Saturday morning; this meant that, like millions of US children, I learned about American culture, history, and government through the Schoolhouse Rock series. On the issue of immigration, Schoolhouse Rock set to music the widely accepted narrative of "The Great American Melting Pot" (click on image for video) where immigrants from (mostly white European) countries willingly jump into a literal pot filled with others happily frolicking in the red, white, and blue "stew." Not surprisingly, no mention is made of the trans-Atlantic slave trade that supplied the forced labor that built the new nation; the catchy song rightly predicts that "any kid could be the president" but falsely claims that "You simply melt right in, it doesn't matter what your skin."[ii] Scholars in the field of Whiteness Studies have demonstrated how assimilation, over time, diminished ethnic and religious differences that once led to the persecution of groups like the  Irish.[iii] Yet descendants of enslaved Africans could not as easily "blend in" to US society. Long after Emancipation, "the problem of the color line" persisted and official and unofficial segregation policies denied equal opportunities to black Americans. In The Souls of Black Folk (1905), WEB DuBois reflected upon the curious position of the African American, introducing the term "double-consciousness" to convey the complicated hybrid status of blacks in the US:

Irish.[iii] Yet descendants of enslaved Africans could not as easily "blend in" to US society. Long after Emancipation, "the problem of the color line" persisted and official and unofficial segregation policies denied equal opportunities to black Americans. In The Souls of Black Folk (1905), WEB DuBois reflected upon the curious position of the African American, introducing the term "double-consciousness" to convey the complicated hybrid status of blacks in the US:

One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

Gender bias aside, DuBois makes a sound argument for the hyphenated identity that many African Americans take for granted today. It might surprise many people to learn  that up until the end of the Civil War, there was widespread support for physically removing blacks from the US. Believing that the country could not sustain and/or tolerate a free black population, even President Lincoln—"the Great Emancipator"—seriously considered sending freed blacks to Haiti, Belize, Panama, or Guyana. The American Colonization Society founded the colony of Liberia in the 1820s and drew the ire of abolitionists like Frederick Douglass who insisted that blacks knew no home other than the US, had earned the right to citizenship, and had already demonstrated their ability to assimilate in the North.

that up until the end of the Civil War, there was widespread support for physically removing blacks from the US. Believing that the country could not sustain and/or tolerate a free black population, even President Lincoln—"the Great Emancipator"—seriously considered sending freed blacks to Haiti, Belize, Panama, or Guyana. The American Colonization Society founded the colony of Liberia in the 1820s and drew the ire of abolitionists like Frederick Douglass who insisted that blacks knew no home other than the US, had earned the right to citizenship, and had already demonstrated their ability to assimilate in the North.

The issue of belonging (in the past and present) is central to my writing, and the complicated project/process of identity formation drives the narrative in A Wish After Midnight. As a mixed-race woman of African descent living in NYC, I am often read as Puerto Rican, Dominican, or Cuban; in Brooklyn, where the majority of black is Caribbean, I live and "blend in with" neighbors who speak dozens of languages, practice as many religions, and otherwise embody the multiplicity of blackness in the US. Like many immigrants from the African diaspora, I identify more with the global South than the US South and I wanted to write a novel that would reflect the hybrid identities of the teens I was teaching in Brooklyn. According to the 2010 census, "12.6 percent of the U.S. population…self-identified with the Black or African American category;" more than 90 percent of those blacks were born in the United States, but the number of foreign-born blacks (originating from the Caribbean, Africa, and Central and South America) is on the rise: "The black immigrant population…has grown 47% since 2000 to 3.1 million."[iv] Many of these immigrants live in NYC.

My two teen protagonists, Genna and Judah, have conflicting plans for the future: fifteen-year-old Genna hopes to attend an Ivy League school and become a psychiatrist; Judah, a sixteen-year-old Jamaican immigrant and Rastafarian, sees no future for himself in the US and believes—like his fellow Jamaican, Marcus Garvey—that the destiny of black people is to return to Africa. For Judah, New York City is "Babylon," a place of confusion and corruption; he sees Genna's "American Dream" as a delusional attempt to fit into a society that clearly has no place for blacks besides the bottom rung of the social ladder. But Genna resists his cynicism and his plan to abandon the US:

My two teen protagonists, Genna and Judah, have conflicting plans for the future: fifteen-year-old Genna hopes to attend an Ivy League school and become a psychiatrist; Judah, a sixteen-year-old Jamaican immigrant and Rastafarian, sees no future for himself in the US and believes—like his fellow Jamaican, Marcus Garvey—that the destiny of black people is to return to Africa. For Judah, New York City is "Babylon," a place of confusion and corruption; he sees Genna's "American Dream" as a delusional attempt to fit into a society that clearly has no place for blacks besides the bottom rung of the social ladder. But Genna resists his cynicism and his plan to abandon the US:

I ask Judah what's so important about Africa, why he can't wait 'til he's done with school. And Judah says he's already done with school, that he won't learn anything in an American college except lies and misinformation. So then I ask Judah why he doesn't just go back to Jamaica if he doesn't like it here. And Judah says, "Sankofa, Gen. Return to your source."

…"But you're Jamaican," I argue.

Judah…shakes his head solemnly. "African, Gen. All of us—no matter where we're born or where we are now—we come from Africa. We're African."

I don't really like it when Judah talks that way…when Judah starts talking about Africa, his Jamaican accent returns—it's like he becomes somebody else, someone who's not like me…I may not know everything about the continent of Africa, but I'm not ignorant—at least not as ignorant as Judah seems to think I am. Judah acts like there's something wrong with me just 'cause I don't hate the United States. I do hate living in the ghetto, and I definitely want to get out of here someday, but I'm not ashamed of being American. And I'm not ashamed of being African, either. That's why we call ourselves African Americans—'cause we're both, not just one or the other. But Judah doesn't see it that way. (56-57)

But Genna isn't so naïve as to think that reaching her goals will be easy; her African American mother warns her against internalizing the "ghetto mentality" that has already ensnared Genna's older siblings, and she knows that many of the rules of success don't apply when you're "young, gifted, and black"—and female, and poor. Genna befriends an elderly Danish man while visiting the local botanic garden but understands that his vision of the US is outdated at best and quite likely skewed by his own privilege:

But Genna isn't so naïve as to think that reaching her goals will be easy; her African American mother warns her against internalizing the "ghetto mentality" that has already ensnared Genna's older siblings, and she knows that many of the rules of success don't apply when you're "young, gifted, and black"—and female, and poor. Genna befriends an elderly Danish man while visiting the local botanic garden but understands that his vision of the US is outdated at best and quite likely skewed by his own privilege:

Mr. Christiansen's a really sweet man. So I just bite my tongue and listen while he talks about America being "the land of opportunity," or "the great melting pot." I want to ask Mr. Christiansen what happens to the folks who get left at the bottom of the pot. I'm thinking whoever's down there probably gets burned. Not just black people, either. A while back they executed a white man for blowing up a government building in Oklahoma…It takes a whole lot of hate to do something like that. Papi, he didn't like America and that's why he left. But that white man, he made a bomb and killed a hundred and sixty-eight people. And never said he was sorry…

Mr. Christiansen sees things differently…Maybe he just sees what he wants to see. Maybe he can do that 'cause he's old and white. All I know is when I look around me, I only see what's real. (28-29)*

Genna thinks of herself as a realist and so initially believes she must be dreaming when a portal opens in the garden late one night and she is drawn into the past. Though her mother has tried to prepare her to face the ugly reality of racism, Genna struggles to survive in the 19th century; believed to be a fugitive slave, she must resist virulent racism, fend off sexual predators, and escape a mob of Irish immigrants that rampages through the city during the 1863 Draft Riots. In A Wish After Midnight, the history of terrorism in the US doesn't begin with 9/11 and so is an internal rather than an external threat; for Genna, Osama bin Laden isn't Public Enemy #1—that (dis)honor goes to Timothy McVeigh, the white "all-American boy" who helped to perpetrate the 1995 Oklahoma City Bombing. Genna recognizes that many Americans are discontent—not only her father, a Panamanian immigrant who abandoned the family after being unable to find steady work; Mr. Colon "can't get anything started" in his adopted home and bitterly concludes that "in America, a black man can't even be a man" (6).

Genna thinks of herself as a realist and so initially believes she must be dreaming when a portal opens in the garden late one night and she is drawn into the past. Though her mother has tried to prepare her to face the ugly reality of racism, Genna struggles to survive in the 19th century; believed to be a fugitive slave, she must resist virulent racism, fend off sexual predators, and escape a mob of Irish immigrants that rampages through the city during the 1863 Draft Riots. In A Wish After Midnight, the history of terrorism in the US doesn't begin with 9/11 and so is an internal rather than an external threat; for Genna, Osama bin Laden isn't Public Enemy #1—that (dis)honor goes to Timothy McVeigh, the white "all-American boy" who helped to perpetrate the 1995 Oklahoma City Bombing. Genna recognizes that many Americans are discontent—not only her father, a Panamanian immigrant who abandoned the family after being unable to find steady work; Mr. Colon "can't get anything started" in his adopted home and bitterly concludes that "in America, a black man can't even be a man" (6).

When her abuela follows her father back to Panama, Genna finds it difficult to identify with her Afro-Latino heritage and gets no encouragement at home; her mother says, "If you're going to learn another language, you might as well learn how to talk white" because "in America, that's the only language that really counts" (50). Genna explains:

I speak a little Spanish, but not much. Just what I learned at school. Mama always told us we were black, not Hispanic. She says in America, it doesn't matter where you're from or what language you speak. Black is black, and you might as well get used to it. And if you are black, then you better speak English 'cause that's what white folks speak. (5)

Genna's mother rejects cultural or ethnic hybridity and pressures her children to accept the American racial binary of black versus white. Although her three children have different skin tones and Afro-Latino/indigenous heritage, Mrs. Colon tries to reduce them to what Elizabeth Alexander calls "bottom line blackness," a kind of generic identity "which erases other differentiations and highlights race.[v] Alexander contends that all blacks in the US are bound to one another by "sometimes subconscious collective memories" that "reside in the flesh" and are triggered by contemporary spectacles of violence enacted upon black bodies. Admitting her theory is somewhat "romantic," Alexander argues that published images of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till (lynched in 1955) became "the basis for a rite of passage that indoctrinated…young people into understanding the vulnerability of their own black bodies…and the way in which their fate was interchangeable with Till's. It was also a step in the consciousness of their understanding themselves as black in America" (92). But do immigrants from across the African diaspora really share this collective consciousness? Can factors like gender, sexual orientation, and nationality be so easily dismissed?

This unifying impulse succeeds at times, but "the bottom" too often relies upon a US-centric construction of blackness that erases both complementary and contradictory histories of persecution and resistance from throughout the African diaspora. Before the 2010 census was taken, a group of black immigrants mobilized members of their communities many of whom were checking the "other" box because they identified as Nigerian or Jamaican rather than African American, Negro, or Black. A USA Today article on the subject concluded that,

In a nation where most blacks trace their origins to slavery, immigrants and refugees from the Caribbean and Africa are redefining what it means to be a black American…Many black immigrants' homelands have a history of slavery, but they don't necessarily equate that with the U.S. legacy of slavery…That's why immigrants cling to national origins rather than racial identities.[vi]

Of course, it isn't either/or—it's a "new stew" called hybridity. In writing A Wish After Midnight, it was important to me to develop narrative strategies that would expose the coercive intraracial dynamics at play in the US, while emphasizing the importance of radical traditions of resistance brought to the US from the Caribbean and other corners of the diaspora. Of the sixty black-authored novels published in the US last year, I found just half a dozen with black protagonists who had at least one immigrant parent. New York is the publishing capital and it is a city of immigrants; my next project is to develop a Diversity in Publishing Network here in the US so that stories which challenge traditional notions of American-ness have a better chance of reaching young readers.

*Last month I read from this chapter of Wish as part of the "Myth and Magic" night at Franklin Park; they've posted the video on their YouTube channel, if you're interested:

[i] Stephanie Kuenn, "Are All Lists Created Equal? Diversity in Award-Winning and Bestselling Young Adult Fiction," June 14, 2011.

[ii] Lyrics by Lynn Ahrens.

[iii] See How the Irish Became White by Noel Ignatiev.

[iv] Haya El Nasser, "Black coalition pushes for 'unified' 2010 Census tally," March 3, 2010.

[v] Elizabeth Alexander, "'Can You Be BLACK and Look at This?': Reading the Rodney King Video(s)," in The Black Public Sphere, edited by The Black Public Sphere Collective (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995) 84.

[vi] El Nasser: "Somebody from Jamaica may not identify themselves as African-American, black or Negro," says Melanie Campbell, executive director of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation who helped found the Unity Diaspora Coalition. "This is about understanding that the black population is not monolithic but that we're all part of the American experience."

June 19, 2011

Father's Day

June 15, 2011

vertical integration

Many thanks to Debbie Reese for posting this important article on Facebook: "."

Many thanks to Debbie Reese for posting this important article on Facebook: "."

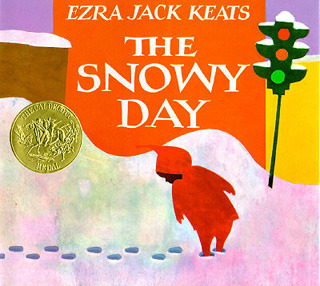

NEW YORK, June 14, 2011 /PRNewswire-USNewswire/ — Nearly eight in ten (78%) U.S. adults believe that it is important for children to be exposed to picture books that feature main characters of various ethnicities or races—but one-third (33%) report that it is difficult to find such books, according to a recent survey that was commissioned by The Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to enhancing the love of reading and learning in all children.

The telephone survey, conducted in April by Harris Interactive on behalf of The Ezra Jack Keats Foundation surveyed 1,001 U.S. adults and found that nearly three-quarters of parents (73%) and half of all adults (49%) have purchased a children's picture book with a protagonist of a different race or ethnicity than the child who will be reading the book. Whereas, only 10% consider it important to match the race or ethnicity of the main character of a picture book to the race or ethnicity of the child who will be receiving the book.

"It's reassuring that so many adults recognize the value in exposing children to books that portray people of all colors and ethnicities," says Deborah Pope, Executive Director of The Ezra Jack Keats Foundation. "What's disheartening though is that, even today, these books are few and far between," adds Pope, who notes that only 9% of 3,400 books published in 2010 for children and teens had significant minority content.

So which comes first? People don't buy multicultural titles because bookstores don't carry them, or bookstores don't carry those titles because people don't come in to buy them? One solution is to launch a new initiative that controls all the stages of book production. My agent told me about this PW article a few days ago and now it's up on Facebook, too. I like this idea but worry that start-ups and outsourcing will give the big publishing houses an excuse to preserve their all-white operations:

Looking to provide a publishing platform for serious literary works, Brooklyn indie publisher Akashic Books is teaming with three notable African-American publishing and bookselling figures to launch Open Lens, a new imprint specializing in quality fiction and nonfiction aimed at the African-American reading audience. The new imprint will be called Open Lens and will debut in September with Makeda, a new novel by Randall Robinson, founder of the human rights and social justice organization TransAfrica.

Open Lens is a co-venture between Akashic Books and literary agents Marie Brown and Regina Brooks along with Hue-Man Bookstore owner Marva Allen and initial guest editor, former Random House executive editor Janet Hill Talbert. Akashic Books has long focused on the African-American market with a list of titles focused on African-American, African, and Caribbean authors.

June 14, 2011

evidence of things unseen

I just finished an author visit at a fabulous school in Cobble Hill. I concluded by telling them about Ship of Souls, which I'm still hoping will be published early in 2012. When I wrapped up my presentation, a boy shot his hand in the air and asked, "Are there really ghosts living under Prospect Park?" I'm used to kids asking me about Marcus, the older brother in Bird who succumbs to drug addiction. And I don't mind telling them about my own brother and his struggle to make good choices in his life. I'm writing a conference paper now that begins with a summary of my father's life—including the affair that ended his marriage to my mother. I think I'm a pretty open person and I like to model ways of theorizing my own experiences. Today I told the kids about the phoenix dying in flames as a new bird is born from the ashes–hands flew into the air: How did it start the fire? What did it eat? Where did it live? Is that a real bird?"

I just finished an author visit at a fabulous school in Cobble Hill. I concluded by telling them about Ship of Souls, which I'm still hoping will be published early in 2012. When I wrapped up my presentation, a boy shot his hand in the air and asked, "Are there really ghosts living under Prospect Park?" I'm used to kids asking me about Marcus, the older brother in Bird who succumbs to drug addiction. And I don't mind telling them about my own brother and his struggle to make good choices in his life. I'm writing a conference paper now that begins with a summary of my father's life—including the affair that ended his marriage to my mother. I think I'm a pretty open person and I like to model ways of theorizing my own experiences. Today I told the kids about the phoenix dying in flames as a new bird is born from the ashes–hands flew into the air: How did it start the fire? What did it eat? Where did it live? Is that a real bird?"

My answer? The phoenix is an ancient mythological bird that originated in Africa, though there are competing versions of the story in other parts of the world. That usually gets a blank stare. "So…is it real?" Today I tried answering it this way: "A myth is a story that's been told over and over for hundreds–even thousands–of years. And the story still has meaning for people today." Another blank stare. So I finished by saying, "I believe the story." I do. Just like I believe in fairies and mutants with special abilities. If I didn't believe in them, I couldn't write convincing stories about them. And storytelling means a lot to me. But is it right to say that to kids? I'm a bit nervous about an underground scene in SoS that involves subway trains—I don't want kids searching for a way underground, and I certainly don't want them imitating the dangerous moves the characters make in the book. I don't want them trying to pry off the plaque on the boulder in Prospect Park. But once you set a child's imagination on fire, can you control the consequences? Maybe not, though I do think I can manage their expectations somewhat. The goal is to encourage them to keep dreaming, rather than attempting to recreate the world of the book in the here and now. And ultimately, I have to trust kids to draw a line between that dream world and reality. Even though I know that line is riddled with gaps…

My answer? The phoenix is an ancient mythological bird that originated in Africa, though there are competing versions of the story in other parts of the world. That usually gets a blank stare. "So…is it real?" Today I tried answering it this way: "A myth is a story that's been told over and over for hundreds–even thousands–of years. And the story still has meaning for people today." Another blank stare. So I finished by saying, "I believe the story." I do. Just like I believe in fairies and mutants with special abilities. If I didn't believe in them, I couldn't write convincing stories about them. And storytelling means a lot to me. But is it right to say that to kids? I'm a bit nervous about an underground scene in SoS that involves subway trains—I don't want kids searching for a way underground, and I certainly don't want them imitating the dangerous moves the characters make in the book. I don't want them trying to pry off the plaque on the boulder in Prospect Park. But once you set a child's imagination on fire, can you control the consequences? Maybe not, though I do think I can manage their expectations somewhat. The goal is to encourage them to keep dreaming, rather than attempting to recreate the world of the book in the here and now. And ultimately, I have to trust kids to draw a line between that dream world and reality. Even though I know that line is riddled with gaps…

June 11, 2011

fill in the blank

Be sure you stop by Multiculturalism Rocks! because Nathalie's got a great interview with Torrey Maldonado, author of Secret Saturdays. Father's Day is fast approaching, and you won't want to miss this thoughtful piece about absent fathers, substitutes, and the role of comic books in this author's life. Then swing by Crazy Quilts to hear about a brand new comic book—Static—that Edi discovered. I just watched X-Men 3 a few days ago (my favorite in the franchise) and wondered why all the PoC mutants were homeless/punk/bad guys while all the bright-eyed students at Xavier's prep school were white…

Be sure you stop by Multiculturalism Rocks! because Nathalie's got a great interview with Torrey Maldonado, author of Secret Saturdays. Father's Day is fast approaching, and you won't want to miss this thoughtful piece about absent fathers, substitutes, and the role of comic books in this author's life. Then swing by Crazy Quilts to hear about a brand new comic book—Static—that Edi discovered. I just watched X-Men 3 a few days ago (my favorite in the franchise) and wondered why all the PoC mutants were homeless/punk/bad guys while all the bright-eyed students at Xavier's prep school were white…