Zetta Elliott's Blog, page 85

September 4, 2011

let "the help" tell their own stories

Need some help making sense of The Help? Then stop by Amy Reads and join her exploration of the REAL conditions of black maids working in white households. Amy and Amanda are using the recommended reading list prepared by the Association of Black Women Historians to address these concerns:

Need some help making sense of The Help? Then stop by Amy Reads and join her exploration of the REAL conditions of black maids working in white households. Amy and Amanda are using the recommended reading list prepared by the Association of Black Women Historians to address these concerns:

1. I'm all for authors having the option to write whatever they want. But for that to work, we need a level playing field where all people can tell their stories. If one group is profiting of the stories of another group, as seems to always happen, that is where the issue comes in. If you've read this book, have you also looked up similar works by African American authors?

2. Way too many people are willing to see The Help as historical fiction and accept the view Stockett gives of a white woman helping the poor black maids who love their jobs. And if readers aren't willing to engage and seek out the truth, that is where the second issue comes in. In this book we have, essentially, a white-washed truth. So again, if you've read this book, have you also looked into some of the real truth of the civil rights movement?

I've read some of the novels on the reading list so will try to join in—how about you? Here are the books Amy and Amanda will be discussing:

Fiction:

Like one of the Family: Conversations from A Domestic's Life, Alice Childress

The Book of Night Women by Marlon James

Blanche on the Lam by Barbara Neeley

The Street by Ann Petry

A Million Nightingales by Susan Straight

Non-Fiction:

Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household by Thavolia Glymph

To Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors by Tera Hunter

Labor of Love Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present by Jacqueline Jones

Living In, Living Out: African American Domestics and the Great Migration by Elizabeth Clark-Lewis

Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody

September 2, 2011

Reimagining History at the BK Book Festival 2011

I hope you'll attend our panel if you're in the tri-state area on September 18th! You can learn more about all the festival events at the BBF Facebook page.

I hope you'll attend our panel if you're in the tri-state area on September 18th! You can learn more about all the festival events at the BBF Facebook page.

1:00 P.M. Reimagining History. National Book Award winner and New York Times Bestselling author Judy Blundell (What I saw and How I lied, and Strings Attached), Coretta Scott King Award Winners, Victoria Bond and T.R. Simon (Zora and Me), and best-selling author Nick Bertozzi (Lewis and Clark) discuss what it takes to tap into and re-imagine unforgettable characters that bring us mystery and adventure wrapped in emotional and timeless settings. Moderated by Zetta Elliott, author of the novel A Wish After Midnight.

August 28, 2011

sucked in

I'm a little worried about this bog. The semester's about to start and I just created a blog for my job (check it out: CESatBMCC); I might need to take a break from Fledgling so that I can wear my professor hat all the time. Then again, do I ever really take it off? I'm sure topics will come up that I can't fully address on the work blog. This weekend I feel like I've been swept away…Hurricane Irene was pretty much what I expected—more of a tropical storm that didn't really disturb my life in any significant way (thanks to everyone who checked on me just the same!). Woke up this morning and the rain had already stopped and the wind was blowing gently enough for the windows to be reopened. I didn't lose power and I have food in the house but with the entire NYC transit system shut down, there isn't anywhere to go. So I'm doing what I usually do on a Sunday afternoon: daydreaming, writing, and watching PBS. A friend asked if I would be getting cable now that I'm working full-time; I'd like to get BBC America (no, not to watch Idris Elba) but it's hard to imagine anything on cable really competing with the  programming on PBS. Global Voices is one of my favorite shows and they've got a great fall line-up. I just watched the tail end of a film about Robert Kennedy's visit to South Africa in 1966 (RFK in the Land of Apartheid). He concluded his visit with a speech at the University of Witwatersrand and these lines jumped out at me:

programming on PBS. Global Voices is one of my favorite shows and they've got a great fall line-up. I just watched the tail end of a film about Robert Kennedy's visit to South Africa in 1966 (RFK in the Land of Apartheid). He concluded his visit with a speech at the University of Witwatersrand and these lines jumped out at me:

There are those who say that the game is not worth the candle – that Africa is too primitive to develop, that its peoples are not ready for freedom and self-government, that violence and chaos are unchangeable. But those who say these things should look to the history of every part and parcel of the human race. It was not the black man of Africa who invented and used poison gas or the atomic bomb, who sent six million men and women and children to the gas ovens, and used their bodies as fertilizer. Hitler and Stalin and Tojo were not black men of Africa. And it was not the black men of Africa who bombed and obliterated Rotterdam and Shanghai and Dresden and Hiroshima.

Genocide is not foreign to Africa, of course, but in that moment and in that space, it was incredibly powerful to have a white man speak those words. I want to warn my students away from racial chauvinism but there are moments when the comparisons are necessary. Anyway, my head's full of other things but maybe I'll try turning to the new novel. I'm incorporating current events like the earthquake and tsunami in Japan and the massacre in Oslo. And now Irene will have a place in the story as well…

August 24, 2011

get ready to submit your story

About the Award

LEE & LOW BOOKS, award-winning publisher of children's books, is pleased to announce the twelfth annual NEW VOICES AWARD. The Award will be given for a children's picture book manuscript by a writer of color. The Award winner receives a cash grant of $1000 and our standard publication contract, including our basic advance and royalties for a first time author. An Honor Award winner will receive a cash grant of $500.

Established in 2000, the New Voices Award encourages writers of color to submit their work to a publisher that takes pride in nurturing new talent. Past New Voices Award submissions that we have published include The Blue Roses, winner of the Paterson Prize for Books for Young People; Sixteen Years in Sixteen Seconds: The Sammy Lee Story, a Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People and a Texas Bluebonnet Masterlist selection; and Bird, an ALA Notable Children's Book and a Cooperative Children's Book Center "Choices" selection.

Eligibility

1. The contest is open to writers of color who are residents of the United States and who have not previously had a children's picture book published.

2. Writers who have published other work in venues such as children's magazines, young adult, or adult fiction or nonfiction, are eligible. Only unagented submissions will be accepted.

3. Work that has been published in any format is not eligible for this award. Manuscripts previously submitted for this award or to LEE & LOW BOOKS will not be considered.

Submissions

1. Manuscripts should address the needs of children of color by providing stories with which they can identify and relate, and which promote a greater understanding of one another.

2. Submissions may be FICTION, NONFICTION, or POETRY for children ages 5 to 12. Folklore and animal stories will not be considered.

3. Manuscripts should be no more than 1500 words in length and accompanied by a cover letter that includes the author's name, address, phone number, email address, brief biographical note, relevant cultural and ethnic information, how the author heard about the award, and publication history, if any.

4. Manuscripts should be typed double-spaced on 8-1/2″ x 11″ paper. A self-addressed, stamped envelope with sufficient postage must be included if you wish to have the manuscript returned.

5. Up to two submissions per entrant. Each submission should be submitted separately.

6. Submissions should be clearly addressed to:

LEE & LOW BOOKS

95 Madison Avenue

New York, NY 10016

ATTN: NEW VOICES AWARD

7. Manuscripts may not be submitted to other publishers or to LEE & LOW BOOKS general submissions while under consideration for this Award. LEE & LOW BOOKS is not responsible for late, lost, or incorrectly addressed or delivered submissions.

Dates for Submission

Manuscripts will be accepted from May 1, 2011, through September 30, 2011 and must be postmarked within that period.

Announcement of the Award

The Award and Honor Award winners will be selected no later than December 31, 2011. All entrants who include an SASE will be notified in writing of our decision by January 31, 2012. The judges are the editors of LEE & LOW BOOKS. The decision of the judges is final. At least one Honor Award will be given each year, but LEE & LOW BOOKS reserves the right not to choose an Award winner.

August 23, 2011

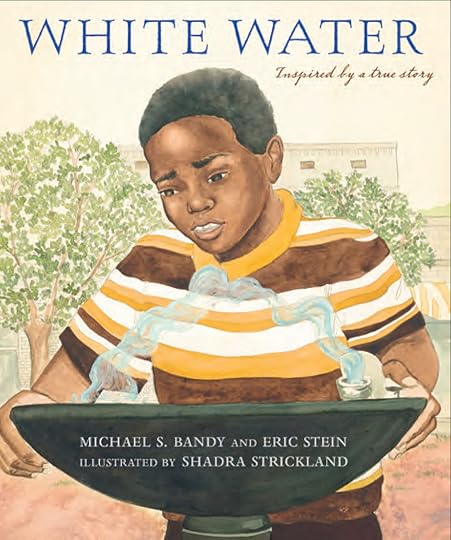

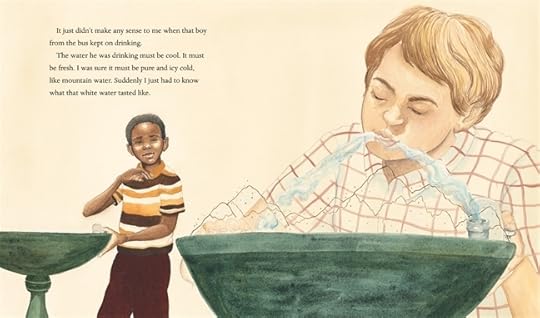

Shadra's new book: White Water

My good friend

Shadra Strickland

has a new book out:

White Water

by Michael S. Bandy and Eric Stein. It's available today and the illustrations are amazing! Shadra kindly took a moment out of her busy schedule to answer some questions about the book:

My good friend

Shadra Strickland

has a new book out:

White Water

by Michael S. Bandy and Eric Stein. It's available today and the illustrations are amazing! Shadra kindly took a moment out of her busy schedule to answer some questions about the book:In the blogosphere there has been a sense of fatigue when it comes to Civil Rights Movement stories, and this is your second project from that era (Our Children Can Soar). How do you approach this particular historical moment and what strategies do you use to create illustrations that seem "fresh"?

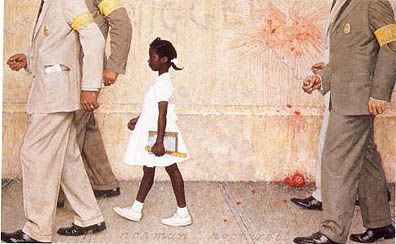

Funny, I don't think of OCCS being a Civil Rights Movement book. The pioneers in the book do span across that time period, but it isn't solely about the Civil Rights Movement. When creating the Ruby Bridges painting in OCCS, I did have to focus on one moment in time which was a lot more challenging for me, especially given the fact that Norman Rockwell's The Problem We All Live With is the iconic image of that historical moment. My goal in that painting was to add to the heart of Ruby Bridges's story. I read her autobiography, watched the movie, and read Steinbeck's account of her first day at school. In the end, the most significant moment was when she bravely crossed the threshold of an all white school. The challenge of coming up with a new perspective is what added to the freshness I think. I was able to add my own ideas to the narrative, which is really important. I have learned that it isn't enough to just reiterate in pictures what the author is already telling us.

My goal in every project is to visually tell an interesting and coherent story and I approached White Water from that angle first. If anything, I was hesitant to add fantasy elements in the art because I didn't want to trivialize the events in the story. I was also against using the same linear devices in White Water that I used in Bird. But thinking about childhood and how imagination is impervious to the harsh realities of life, I felt more confident in telling the story with a few visual surprises that relate solely to the wonder of being a child. When I build a character, I think a lot about their internal world. Michael was very courageous and smart. I thought he probably read the Sunday funnies and had a hero from one of the strips. I researched the local Opelika comic strips but couldn't find anything that I could really use in my art. I then thought of my cousin and how growing up he was never without army men or action figures. It made sense to me that Michael would look to similar symbols of courage as well.

You've won so many awards–the most recent being the Ashley Bryan Award–yet you're still in the early stages of your career. Talk about the impact of earning such acclaim and the future you see for yourself in the changing world of publishing.

Awards are terrifying and exciting all at once. They are fantastic for boosting the ego and validation, but they also make me extremely competitive with myself and self-aware. I always want to see growth in my work, but the awards that I have been honored to accept give me a heightened sense of responsibility in what I do—from the type of stories I accept, to how I tell a story visually. They also make me aware of the impact that picture books have on people's lives and how far reaching they are. When I share a book like Bird or Hurricanes with a stranger and they are moved to tears, it's quite humbling.

I can't predict the future. I do know that I will continue making books and telling stories for as long as I can and I will continue to grow and challenge myself as an artist. If I need to stop making books and find another outlet for my work, so be it. My mantra is simple: do good work and the rest will follow.

August 18, 2011

boys on film

My head's full of stories but I haven't allowed myself to sit and write. The fall semester starts in less than two weeks and I've been obsessing over my syllabi; new courses are always a challenge, especially when the course (African Civilization) falls outside my area of expertise. I like the course I've designed, and keep stumbling across texts that "fit"—like this response to historian David Starkey's racist rant on the BBC. Are the riots a result of "whites becoming black"? Did black people (and Jamaicans specifically) really teach white youth to act out violently? Nabil Abdul Rashid went straight to the Moors: "we taught you how to bathe." He goes on to use historical events to demonstrate that violence and looting are deeply embedded in British culture, predating the arrival of Jamaicans in the UK. He even suggests that the African slave trade was a form of looting…I see an interesting class discussion following this text. I also decided to show Michael Jackson's "Remember the Time" video on the first day of class as an example of how ancient African civilizations manifest in contemporary culture…

Saw two great films in the past week but don't have headroom for a thorough review. Gun Hill Road is an important film about a Latino father who returns from prison to find his beloved son is transitioning to a young woman. Mikey (Harmony Santana) has grown his hair out and regularly performs at a poetry club as "Vanessa." Accepted by her friends, her mother, and her mother's boyfriend Hector, Vanessa nonetheless struggles to live as a teenage girl; she's harassed at school, the boy she's servicing sexually (in part to raise money for breast implants) doesn't want to be seen with her in public, and her father—who was raped in prison—can't accept that his son is rejecting masculinity. Enrique (Esai Morales) learns that his rapist has been released from prison and brutally exacts revenge in an alley; he then takes Mikey to a prostitute and waits outside the bedroom door to make sure his son "becomes a man." Traumatized, Vanessa leaves home and finds sanctuary with Hector (who has also been menaced/mugged by possessive Enrique). This film is incredibly honest and Harmony Santana gives an amazing performance—her difficult sexual encounters left me with a knot in my stomach. But there are moments of tenderness in the film as well, and Enrique softens his stance before leaving the family once more. I have to admit that I left the theater wondering what would happen to Enrique—Vanessa still faces a lot of challenges as a transgender teen, but I felt more confident of her transition than her father's. How likely is he to "become a better man" in prison? At least one of Enrique's friends, though a petty criminal, was able to accept Mikey as Vanessa. Without that kind of support, it doesn't seem likely that Enrique will be able to address his transphobia, nor is he likely to receive treatment for his own trauma as a rape victim.

Attack the Block also attempts to redeem predatory masculinity—like Super 8, this film follows a group of teenage boys who discover that aliens have invaded their government housing project. For the first half hour of the film I had to agree with the white female character (Sam) who, after being mugged at knife point, described the boys as "fucking monsters." Of course, she later realizes that the real monsters are the greater threat and aligns herself with Moses and his crew after they defend her and kill one of the aliens. The best moment in this film—for me—was when Moses' prospective girlfriend jumps into action to save his life; paralyzed by fear, Moses hides as one of his boys gets killed by the aliens, unable to repeat his heroic samurai sword act performed earlier in Sam's apartment. His female counterparts grab a halogen lamp and an ice skate (I'm still laughing as I write this!) and disable the alien, giving Moses time to find his courage. Nonetheless, he's saved by Sam who daringly plunges a kitchen knife into the alien's jaw just as it prepares to devour Moses. There are witty jabs at white liberals throughout the film, and unlike the innocent boys in Super 8, the teens immediately accept Moses' theory that the Feds (police) planted the aliens on their block just as they sent in drugs and guns to decimate the community. The film's ending was pleasantly surprising—Moses realizes his own aggression (killing the lone female alien) is to blame for much of the chaos, and we see (through Sam's eyes) the neglect he faces at home, which made him self-reliant by pushing him into the street. Read against the recent riots that swept across the UK, Attack the Block offers an honest and entertaining look at a multiracial, working-class "band of brothers" who demonstrate loyalty, creativity, courage, and humility. I know it's showing in Toronto and NYC—do go see it if you have the chance.

August 12, 2011

do rioters read?

When I heard that the one store left untouched during the recent riots in London was a bookstore, my heart sank. This article in The Guardian asks all the right questions, including this one: "Are you more or less likely to riot if you read?"

Maybe it's just a question of class. As the author Gavin James Bower says, "Jobs in publishing overwhelmingly go to white, middle-class people. The product reflects this, which isn't much good if you're a working-class kid." If publishing is full of white, middle-class people is it any wonder that bookshops are too? The writing community can be as diverse as it likes – in class, race, religion and genre – but if publishers don't know how to market these books, they're not going to find readers. Or maybe it starts even earlier, in school, where according to the journalist Kieran Yates "young people often don't feel like they can empathise with a syllabus of literature that is so far removed from their own lives".

August 10, 2011

love endures

In June, after attending the ChLA conference, I posted my paper here on the blog along with some of the photos I'd shown in my Powerpoint presentation. Yesterday something miraculous happened: a man who once attended college with my father wrote this email that sent my heart reeling. He has kindly given me permission to share it here on my blog. I know it likely won't mean anything to those who never knew my father, but as Mr. Greene pointed out, others might come across this blog and find meaning in his memory of that place and time. What I've learned from this amazing encounter? Time passes. Love endures.

In June, after attending the ChLA conference, I posted my paper here on the blog along with some of the photos I'd shown in my Powerpoint presentation. Yesterday something miraculous happened: a man who once attended college with my father wrote this email that sent my heart reeling. He has kindly given me permission to share it here on my blog. I know it likely won't mean anything to those who never knew my father, but as Mr. Greene pointed out, others might come across this blog and find meaning in his memory of that place and time. What I've learned from this amazing encounter? Time passes. Love endures.

Hello Ms. Elliot:

Yes I knew your Father. I was not in the graduation picture you have in your blog because I am a few years younger than George. I have thought about things I would like to say to you and now that I am sending you this email I hardly know how to begin. So I'll relate to you the things I remember about George. The first thing one noticed about George, besides his good looks, was his dignity. His bearing and graceful way he carried himself. Not once do I recall ever hearing him complain about anything, and he had much he could have griped about.

EPC [Eastern Pilgrim College] was racist to its core. Generations of ingrained racism that seemed absolutely normal to us whites at the time. And I my dear Lady was the worst of the worst. I was born in Mississippi. My family was Klan, and some knew about or participated in the murders of three civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Miss. in 1964. The year I first went to EPC, I was vocal in my disrespect of black people. I was known on campus as THE racist. So why George chose me, out of all the guys at EPC to accompany him on his home calls to the projects and ghettoes of Allentown and Bethlehem, Pa. I did not know. But I went. He never preached to me. He never said anything to me about my racist views. What he did do was take me from apartment to apartment as he counseled with all of those poor desperately needy people. Most were single mothers with a lot of kids. George selflessly gave of his time and money to help as many as he could, and always sharing the Gospel. Ms. Elliot, he showed me people trapped in poverty with no hope for the future. No way out of their situations. And so we went from place to place and it was all the same, children going hungry, mothers trying to feed four or more kids on a few meagre food stamps, and no husband in sight to help out. He did more to change my attitude and perspective by quietly having me accompany him on his rounds than a thousand lectures ever could have.

But that's not all he did. George did not follow the example of the people at EPC and limit himself to only helping black people. Because they were content with helping only the whites. He reached out to the white gang members in the projects. He worked with them. Talked their language. Arranged for them to play basketball. And took them to Church. Well, that opened up a whole can of worms because the good people of the Pilgrim Holiness Church in Bethlehem, Pa. were none too thrilled with all those rough ghetto kids attending their Church. That was the first time many of them had heard of Jesus Christ outside the context of a swear word. But those good people started to murmur and complain, and soon those kids knew they were not welcome. And all the headway George had made with them was wiped away.

On campus, in the churches, and in the neighborhood George was surrounded by girls. White girls. Now just try to imagine being a handsome, healthy young man, and all those girls every where, and he can't be with any of them. There was a young girl, I think she was a sophomore, and she was beautiful, and she did have a thing for George. It was obvious they liked each other. They became bold and began sitting with each other on the campus park benches just talking. But George knew he would never be allowed to take her out on a date to a concert or anything like the rest of us did. He would never get to hold hands with her, and God forbid if he ever actually got a good night's kiss, like the rest of us did. There was no chance that they would have engaged in sex or immorality because they were Christians, with principles like every one else. But George was black and she was whilte and that's all anyone could see. No sympathy to their plight at all. And I remember thinking what would be the harm? Wow, talk about me doing a 180 degree turn around. But the tongues started wagging and George and the young lady got warned by the administration not to see each other any longer. And I thought that's just not right. George is a good guy, and she's a good girl.

In your blog you alluded to George going through a period when he became militant. I don't know what happened to George after EPC. I got drafted in 1966 and I never saw him again. But down through the years I have thought about him. I just always thought he probably became a preacher. For if ever anyone had a pastor's heart it was George Hood. In the late '70s a black minister, one of two brothers, came down to our Church to preach. He was from Canada, and very soft spoken and eloquent. After one of the services I asked him if he knew George and he said yes he knew him very well. I asked him how he was doing and the minister said George was doing very well and active in the work of his church. I asked him to tell George hello for me and he said he would.

I for one would never blame him if he became bitter. Ms. Elliot, your Father gracefully endured more racism among and from his Christian brethren than most black people are ever exposed to. And he conducted himself with dignity and in doing so in the end he won. Because that college no longer exits. In fact the denomination no longer exists. It was merged with the Wesleyan Methodists.

I hope that I have in no way offended you. I said all of these things to you because sometimes children do not see the tough times their parents may have had. I wish I could see George again just so I could tell him how much I admired him.

Sincerely,

Tom Greene

August 7, 2011

lunch–with attitude

Today we had lunch in Brooklyn with Miss Attitude, otherwise known as Ari, the amazing teen blogger at Reading in Color. I confess, there were times in the past when I wondered if she was really just a teenager—how could one young woman read and write so much on top of her school work and extracurricular activities? But I'm happy to report that Ari is legit, just as impressive in person, and it was a real pleasure to have lunch with her and her mom. We talked books and politics—the politics of books—and then took some photos before parting. Here's Ari with Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich and Lyn Miller-Lachmann. And below is Lyn, Ari, her mom, and me.

Today we had lunch in Brooklyn with Miss Attitude, otherwise known as Ari, the amazing teen blogger at Reading in Color. I confess, there were times in the past when I wondered if she was really just a teenager—how could one young woman read and write so much on top of her school work and extracurricular activities? But I'm happy to report that Ari is legit, just as impressive in person, and it was a real pleasure to have lunch with her and her mom. We talked books and politics—the politics of books—and then took some photos before parting. Here's Ari with Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich and Lyn Miller-Lachmann. And below is Lyn, Ari, her mom, and me.

August 3, 2011

meet Ranger Doug

One of my goals in writing about black history is to ignite the imagination of urban kids—many of whom walk past historical monuments every day without understanding or appreciating their significance. Ship of Souls will come out next year and since the book is dedicated to my cousin Kodie (who lives in Canada), I decided to make a short film for him featuring all the sites mentioned in the story. Today I stopped by the African Burial Ground monument and was lucky to find Ranger Doug Massenberg on duty—I first met Ranger Doug a couple of years ago and had the privilege of taking his fantastic tour of lower Manhattan. His passion for African American history is evident—and contagious! I'm definitely sending my students here for an assignment; my college is just a few blocks away and yet I wonder how many students (and faculty members) have stopped to pay respect…if YOU haven't visited the African Burial Ground museum and monument, put it on your bucket list now. It's necessary viewing…