Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 198

December 7, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – The Highland Servant: John Brown

On 8 December 1826, John Brown, who would become Queen Victoria’s close confidante after Prince Albert’s death, was born at Crathienaird as the second son of John Brown, a tenant farmer, and Margaret Leys. The family would grow to include 11 children – 9 boys and two girls – though some would die in childhood. He would spend his childhood at The Bush Farm, where the family moved when John was five years old. He attended a few terms at Crathie school, but he mostly learned outside of school and picked up the skills of deerstalking, fish spearing, shooting and riding. At the age of 4, he finished his education and joined the workforce.

In the 1840s, he found work on the Balmoral estate though it is unclear preciously how. He herded ponies there for 13s per week. He then took up a position as one of the Balmoral gillies and was still working there when Queen Victoria appeared on the estate with her family. Sir Robert Gordon, who had a longterm lease of Balmoral Castle, died in 1847, and Prince Albert acquired the lease in 1848. Queen Victoria quickly fell in love with the area, and the family returned often. John Brown often accompanied the family as they explored the area. Queen Victoria first mentioned John Brown in her journal on 11 September 1849. Prince Albert also noticed John Brown, and he decided that he should ride on the box of the Queen’s carriage. By 1858, John was her regular attendant out of doors in the Highlands.

In 1861, Queen Victoria was struck by two tragedies – the deaths of her mother and . She was plunged into deep grief but returned to Balmoral the following spring. Here she felt Prince Albert’s presence more than elsewhere. As the Queen became more depressed, her doctor surmised that she needed more fresh air and exercise. It was Princess Alice who suggested that John was brought over since Queen Victoria hated unfamiliar faces. He was subsequently summoned to Osborne House in December 1864 with her favourite pony, Lochnagar. Soon, she was relying on John more and more, and he began taking her for daily rides. Victoria wrote to her uncle King Leopold I of the Belgians, “It is a real comfort for [Brown] is devoted to me – so simple, so intelligent, so unlike an ordinary servant.”

As he grew in her affection, he rose in rank, and by 1872, he was designated “Esquire,” and he received a salary of £400. She wrote to him that year, “You will see in this the great anxiety to show more & more what you are to me & as time goes on this will be more & more seen and known. Every one hears me say you are my friend & most confidential attendant.” Soon, there were rumours that there was more to their relationship and resentment towards John grew in the court and in politics. Her own children regularly complained of remarks made by John. The publication of Queen Victoria’s “Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands, From 1848 to 1861” introduced John Brown to a wider audience.

John also picked up a number of self-imposed duties, including guarding the Queen, and by the 1870s, he was sleeping with a loaded revolver under his pillow. There were several plots to assassinate Queen Victoria, and John was involved in preventing at least one of them. On 29 February 1872, the 17-year-old Arthur O’Connor scaled the fence at Buckingham Palace and sprinted across the courtyard as Queen Victoria returned to Buckingham Palace after a ride through the parks. O’Connor managed to run to the side of the carriage and brushed up against John, who pushed him back. He ran around the back of the carriage with a raised gun and was suddenly face to face with Queen Victoria. Her son Prince Arthur noticed the gun and pushed O’Connor’s hand away, and the gun clattered on the ground. John Brown seized O’Connor and pushed him to the ground. Queen Victoria later wrote to her eldest daughter, “It is entirely owing to good Brown’s great presence of mind and quickness that he was seized.” For his bravery, he was given a medal in gold.

By the late 1870s, John’s health was deteriorating. He regularly drank a lot, which also did not help, and he suffered several bouts of erysipelas. By early 1883, he was clearly very sick even though he tried to continue to serve Queen Victoria. By March, he was suffering from a cold, and his brother called for a doctor. He soon developed a high fever, and he deteriorated fast. By the evening of 25 March, he was delirious. Queen Victoria had no idea how sick he was and wrote, “Vexed that Brown could not attend me, not being well at all, with a swollen face, which is feared is erysipelas.” Two days later, John fell into a coma and never came out of it. He died on 27 March 1883 at 10.40 P.M. It was Prince Leopold who broke the news to Queen Victoria and she later wrote, “Leopold came to my dressing-room and broke the dreadful news to me that my good, faithful Brown had passed away early this morning (?) Am terribly upset by this loss, which removes one who was devoted and attached to my service and who did so much for my personal comfort. It is the loss not only of a servant but of a real friend.”1

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – The Highland Servant: John Brown appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 6, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – Queen Victoria’s half-sister Feodora of Leiningen

Queen Victoria may have grown up without much contact with the outside world, but she had some company in the form of her elder half-sister. Feodora of Leiningen was born on 7 December 1807 to Emich Carl, 2nd Prince of Leiningen and Victoria of Saxe-Coburg and Saalfeld in Amorbach. She had an elder brother, and together they grew up in Amorbach.

Feodora’s father would die in 1814, and her life would change in 1818 when her mother married Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, who was the fourth son of George III. By 1819, the household moved to England as the new Duchess of Kent was pregnant, and they wanted to have the potential heir to the throne on English soil. Her half-sister Victoria was born on 24 May 1819 at Kensington Palace in London. Feodora’s new stepfather would not see his daughter grow up as he died on 23 January 1820. Feodora was also living at Kensington Palace by then, where she received an education from private tutors.

Though the age difference of 12 years certainly affected their relationship, their bond was a close one. Feodora was not very happy at Kensington Palace, however. She would later write, “I escaped some years of imprisonment which you, my poor dear Sister, had to endure after I was married. Often have I praised God that he sent my dear Ernest for I might have married I don’t know whom – merely to get away!”1

On 18 February 1828, Feodora married a man she had only met twice before, Ernst I, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg. He was 13 years her senior and Feodora considered him to be kind and handsome. However, as the half-sister of the future Queen, she could have made a much more magnificent marriage. Victoria acted as a bridesmaid for her sister and Feodora later wrote, “I always see you, dearest, little girl, as you were, dressed in white – which precious lace dress I possess now – going round with the basket presenting favours.”2 Feodora continued to write to her sister and even received an allowance whenever she wished to visit England. Victoria missed her sister terribly and sent many letters, sending news of her dolls and pouring out her feelings. Feodora had six children with her husband, all of which survived to adulthood, but her eldest daughter Elise died at the age of 19 of tuberculosis. Victoria had commissioned a portrait of Elise in 1840, and when Elise died, she sent Feodora a bracelet containing the miniature portrait to which Feodora responded: “I think the miniature very good, and the setting so beautiful, the idea so beautiful … Only with tears, I can thank you!”

Feodora returned to Kensington Palace six years after her marriage, and a delighted Victoria wrote, “At 11 arrived my dearest sister Feodora whom I had not seen for six years. She is accompanied by Ernest, her husband, and her two eldest children Charles and Elise. Dear Feodora looks very well but is grown much stouter since I saw her.”3 Upon her departure in July, Victoria wrote, “I clasped her in my arms, and kissed her and cries as if my heart would break, so did she dearest sister. We then tore ourselves from each other in the deepest grief. When I came home, I was in such a state of grief that I knew not what to do with myself. I sobbed and cried most violently the whole morning.”4

Feodora in 1859 (public domain)

Feodora in 1859 (public domain)Feodora’s husband died in 1860, and Queen Victoria’s husband Albert followed the next year. Victoria had hoped that her sister would join her in England and share in her grief. Feodora’s visited her sister in 1863 but found Victoria’s grief unbearable.

Feodora died on 23 September 1872, the same year as her youngest daughter. Feodora and Victoria had last seen each other earlier that year when Feodora was already terminally ill. Victoria wrote after her sister’s death: “Can I write it? My own darling, only sister, my dear excellent, noble Feodora is no more! This was to have been and is still a day of rejoicing for all the good Balmoral people, on account of dear Bertie’s5 first return after his illness; and I am here in sorrow and grief, unable to join in the welcome. God’s will be done, but the loss to me is too dreadful! I stand so alone now, no near and dear one near my own age, or older, to whom I could look up to, left! All, all fone! She was my last near relative on an equality with me, the last link to my childhood and youth. My dear children, so kind and affectionate, but no one can really help me.”6

A letter dated 1854 was found among Feodora’s paper after her death for Victoria:”I can never thank you enough for all you have done for me, for your great love and tender affection. These feelings cannot die, they must and will live in my soul – till we meet again, never more to be separated – and you will not forget.”7

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – Queen Victoria’s half-sister Feodora of Leiningen appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 5, 2019

From Queen Victoria to the Empress Frederick – 6 December 1891

From Queen Victoria to the Empress Frederick – Windsor Castle, 6 December 1891

Since yesterday the great event of Eddy’s1 engagement with May Teck2 has taken place. People here are delighted and certainly she is a dear, good and clever girl, very carefully brought up, unselfish and unfrivolous in her tastes. She will be a great help to him. She is very fond of Germany too and is very cosmopolitan. I must say that I think it is far preferable than eine kleine deutsche Prinzessin (a little German Princess) with no knowledge of anything beyond small German courts etc. It would never do for Eddy. What Mary3 will do without May, I cannot think, for she was her right hand. I can well understand that many things must make you very sore, but many are really unavoidable…

Tonight we have Prince Napoléon here. He is very good-looking with a fine presence and pleasing. We met him at Farnborough Hill at the Empress’s4 yesterday where we lunched. On coming home I found Eddy who came himself to announce the news of his engagement to me…5

The post From Queen Victoria to the Empress Frederick – 6 December 1891 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Elizabeth Widville, Lady Grey: Edward IV’s Chief Mistress and the ‘Pink Queen’ by John Ashdown-Hill Book Review

Elizabeth Woodville (or Widville, as used by the author of this book) was Queen of England as the wife of King King Edward IV of England during turbulent times. As a slightly older widow with two sons already and a Lancastrian background, she was seen as an unsuitable match for the Yorkist King. Nevertheless, they married – despite him perhaps having already married someone else – and she was introduced to the court as the new King. Over the years, as Edward’s fortunes went up and down, Elizabeth gave birth to several children, including the Princes in the Tower and Elizabeth of York, whose marriage to Henry Tudor would eventually unite the warring houses.

Elizabeth Widville, Lady Grey: Edward IV’s Chief Mistress and the ‘Pink Queen’ by John Ashdown-Hill is the latest book on Elizabeth Woodville, and I could already tell from the title that it was going to be an interesting one. The use of the name ‘Widville’ and the use of the word ‘mistress’ in the title already suggested to me that the author did not particularly like the subject. The disdain for Elizabeth simply drips off the pages, and I often found myself rolling my eyes as the author referenced himself. Truth be told, there are more objective books out there.

John Ashdown-Hill has written 14 books, and this one would be his last. He passed away of motor neurone disease on 18 May 2018. He was heavily involved in finding the remains of King Richard III.

Elizabeth Widville, Lady Grey: Edward IV’s Chief Mistress and the ‘Pink Queen’ by John Ashdown-Hill is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post Elizabeth Widville, Lady Grey: Edward IV’s Chief Mistress and the ‘Pink Queen’ by John Ashdown-Hill Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 4, 2019

Princess Deokhye – The tragic tale of Korea’s last Princess

Princess Deokhye was born on 25 May 1912 at the Changedeok Palace in Seoul as the youngest daughter of Emperor Gojong of Korea and a concubine by the name of Yang Gui-in. She wasn’t recognised as a Princess until 1917 because she was not born the daughter of a Queen. Her father had been forced to abdicate in 1907, and he had been succeeded by his son and Deokhye’s half-brother Emperor Sunjong. The Empire ended in 1910 when it was annexed by Japan. Her father was already 59 when she was born, but he was delighted by her, and she became the darling of the nation.

She was entered into the registry of the Imperial Family in 1917 after her father persuaded the Governor-General of Korea. Her father died quite suddenly on 21 January 1919. Deokhye was taken to Japan in 1935, supposedly to continue her studies. The Japanese probably preferred having the nation’s darling out of the spotlight. Although she was allowed to go to school, she was ostracised and feared for her own safety. She was only temporarily allowed to return to Korea for her mother’s funeral in 1930, but she was not given the proper clothing to wear. By early 1930, she began to suffer difficulties with her mental health, which manifested firstly with sleepwalking. She was moved to the home of her other half-brother Crown Prince Yi Un, who lived in Tokyo. Her health deteriorated further, and she often missed meals. She was diagnosed with precocious dementia – now usually called schizophrenia.

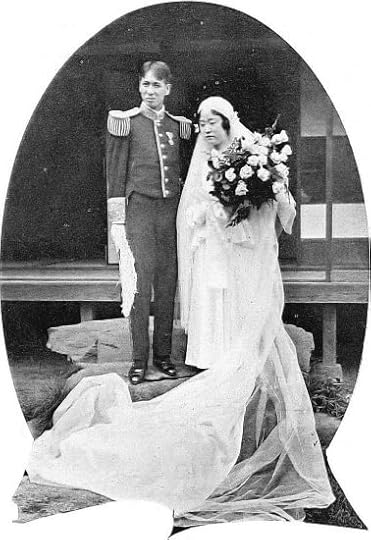

(public domain)

(public domain)Despite this, Empress Teimei of Japan, consort of Emperor Taishō, arranged for her to marry a Japanese aristocrat, Count Sō Takeyuki. When her condition improved slightly, the marriage immediately went ahead. They were married on 8 May 1931, and she gave birth to a daughter named Masae the following year on 14 August 1932. By 1933, Deokhye was again unwell, and she was admitted to a mental hospital where she would spend many years.

When Japan was defeated in the Second World War, Korea achieved its independence once more. Japan’s nobility lost their titles, and the peerage was abolished. Deokhye and her husband were divorced in 1953, and he remarried some time in 1955. The biggest tragedy and mystery came in 1956 when her daughter ran away, leaving a letter resembling a suicide note. She was never seen again. Deokhye’s mental health suffered as a result, and she was able to return to Korea in 1962, where she was admitted to the Seoul National University Hospital. After the Korean War, Deokhye and her surviving family members were granted a small stipend. She lived in the Changdeokgung Palace with her sister-in-law, Yi Bangja. She continued to receive treatments from the hospital, but there were many things that she often did not recognise.

Princess Deokhye died on 21 April 1989 after catching a cold – she was 76 years old. By then, she had reportedly been suffering from aphasia, which means that one can not speak or understand others.

In recent years, Princess Deokhye’s tragic life has been highlighted with an exhibition about her life in 2012 and the film “The Last Princess” in 2016.

The post Princess Deokhye – The tragic tale of Korea’s last Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Starz orders Tudor drama ‘Becoming Elizabeth’

Starz is going to explore the future Queen Elizabeth I’s younger years with a new show called “Becoming Elizabeth.”

“The world of “Becoming Elizabeth” is visceral and dangerous – judgments are rendered quickly and no one is safe,” said Starz CEO Jeffrey A. Hirsch in a statement. “This series explores the Tudor reign and young Elizabeth, who would become England’s ‘Gloriana’ and one of history’s most dynamic figures, through a new lens which we think viewers will find highly engaging.”

“Becoming Elizabeth” is being created and written by playwright and TV screenwriter Anya Reiss. “Drama seems to skip straight from Henry VIII’s turnstile of wives to an adult white-faced Gloriana. Missing out boy kings, religious fanatics, secret affairs and a young orphaned teenager trying to save herself from the vicious scramble to the top. I should have found it hard to relate to 500-year-old royalty but Elizabeth lived in dangerous, polarising times and often made terrible hormone-fuelled decisions. I’ve found writing her story a thrilling experience,” said Reiss.

Starz has some experience with the Tudor era – it also developed “The Spanish Princess.” It also developed “The White Queen” and “The White Princess.”

The post Starz orders Tudor drama ‘Becoming Elizabeth’ appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 3, 2019

Sophia Dorothea of Hanover – The Olympia of the Hohenzollerns (Part two)

The accession of her father as King of Great Britain in 1714 led to her entertaining the thought of a marriage between her eldest daughter Friedrike Wilhelmine and Prince Frederick – later Prince of Wales and the father of King George III. This marriage never happened after rumours were spread that the young Princess was deformed and had epilepsy. In 1719, her husband was seriously ill, and Sophia Dorothea was granted the regency in case of his death. Luckily, he survived his illness. The education of their eldest son was a sore point between the parents, and Friedrike Wilhelmine later wrote, “Whatever my father ordered my brother to do, my mother commanded him to do the very reverse.” In 1729, the Crown Prince was placed under the care of new governors, as his father hoped to reform his ways – he had recently become friends with two men with different ideas. When he tried to escape his new governors, he was captured and brought back as a prisoner. Sophia Dorothea was implicated in having facilitated his escape. Frederick William cruelly told his wife that their son was dead, and she screamed, “What! Have you murdered your son? Mon Dieu, mon fils! (My god, my son!)” He also happened upon his eldest daughter Friedrike Wilhelmine during his rage and nearly beat her to death.

Frederica Louise was the first of her children to marry. On 30 May 1729 in Berlin, she married Karl Wilhelm Friedrich, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach. After the awful scene with her father, Friedrike Wilhelmine was given the choice of three husbands, and she picked the future Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, on the condition that her brother would be released. They were married on 20 November 1731, and the crown prince was set free after the wedding. Sophia Dorothea believed her daughter to be weak and acted coldly to her future son-in-law. She wrote that she would “never forgive her.”

Wedding would follow wedding in the coming years. The crown prince married Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern on 12 June 1733, followed by Philippine Charlotte’s wedding to the future Charles I of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel on 2 July 1733, Sophia Dorothea junior married Frederick William, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt on 10 November 1734, Augustus William married Luise of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel on 6 January 1742, Louisa Ulrika married the future Adolf Frederick, King of Sweden on 17 July 1744, Henry married Wilhelmina of Hesse-Kassel on 25 June 1752 and Augustus Ferdinand married Elisabeth Louise of Brandenburg-Schwedt on 27 September 1755.

Shortly after the crown prince’s marriage, Frederick William’s health had begun to decline more steeply than before. His health had been bad for years. Sophia Dorothea nursed him dutifully during his year of ill-health. During these years, he often used a wheelchair to get around. As death approached, he made his own funeral arrangements and ordered a postmortem to be done. He also had his coffin brought to him for inspection. In his last hours, he said to Sophia Dorothea, “I have but a few hours to live, and I would at least have the satisfaction of dying in your arms.” In the end, he died on 31 May 1740 in his eldest son’s arms as Sophia Dorothea was being led from the death bed. Despite his often harsh treatment of her, Sophia Dorothea was deeply affected by her husband’s death.

When she later addressed her son as “Your Majesty,” he interrupted her and said, “Always call me your son; that title is dearer to me than the royal dignity.” In addition, he also remained standing until she requested him to sit. They remained close over the next years, and he often came to see her first when he returned from a campaign. From 1756 onwards, her health began to decline. Shortly before her death, she wrote to her daughter Philippine Charlotte, “My health remains much in the same state. I suffer always from great weakness, although I do all I can to recover my strength; nevertheless, I remain very feeble. I see that I must arm myself with much patience.” The letter arrived on 28 June 1757, and Sophia Dorothea died on that day.

Her son – in the midst of battle – shut himself up in his tent when he received the news. He would see no one. He wrote to his sister Friedrike Wilhelmine, “A new sorrow that depresses us! We do not have a mother anymore. This loss puts the crown on my pain!”1

The post Sophia Dorothea of Hanover – The Olympia of the Hohenzollerns (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 2, 2019

Sophia Dorothea of Hanover – The Olympia of the Hohenzollerns (Part one)

Sophia Dorothea of Hanover was born on 26 March 1687 at the Leineschloss in Hanover as the daughter of the then Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Lüneburg, later King George I of Great Britain, and Sophia Dorothea of Celle. Her elder brother became King George II of Great Britain in 1727. Her parents’ marriage had quickly turned sour, and it was dissolved in 1694, and her mother was imprisoned in Ahlden. Her father’s mistress Melusine von der Schulenburg, gave birth to three daughters over the following years.

She and her brother spent their youth at either the Leineschloss or at Herrenhausen. Both palaces suffered damage during the Second World War but were subsequently rebuilt. With their mother gone and their father caring little for them, Sophia Dorothea and her brother fell under the care of their grandmother, Sophia. Sophia hired a governess named Anna Katharina von Harling, and Sophia Dorothea received a formal education. She was taught court etiquette, history, geography, religion and several foreign languages. In 1701, the British succession was settled in her grandmother’s favour if Queen Anne were to die childless, and Sophia was her closest living Protestant relative. Sophia was a granddaughter of King James I and VI through Elizabeth Stuart, the Winter Queen.

Around this time, plans for Sophia Dorothea’s marriage were being discussed. She was to marry her cousin Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia. Sophia Dorothea remained blissfully unaware of the future that was being plotted for her for now. She celebrated her 18th birthday in 1705. On 22 August 1705, her brother was the first to get married – to Caroline of Ansbach. The following year – on 16 June 1706 – her engagement to Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia was announced. In preparation for the wedding and perhaps for a rest after all the engagement festivities, Sophia Dorothea was sent to Pyrmont to take the cure. From Pyrmont, she wrote to her fiance of her health. For her regal bearing and gracious manners, she was nicknamed, “Olympia.”

On 28 November 1706, Sophia Dorothea and Frederick William were married in the White Hall at the Berlin Stadtschloss. She had only arrived in Berlin the day before. Upon marriage, she immediately became the first lady of Prussia as her mother-in-law had passed away the previous year, and her father-in-law would not remarry until 1708. She was in her element and enjoyed all the festivities – unlike her new husband. Frederick William was “polite” to Sophia Dorothea, but the marriage was cold otherwise. During her honeymoon, Frederick William went hunting, and Sophia Dorothea was bored out of her mind. She quickly fell pregnant and just over a year after their wedding – on 9 December 1707 – she gave birth to a son – Prince Frederick Louis. Tragically, the infant prince lived for just five months – dying on 15 May 1708. His parents were not with him at the time. Sophia Dorothea withdrew into herself and did not mention the death of her son.

Her marriage deteriorated even more, and Frederick William had even begun to speak of separation. In desperation, she wrote to him, “You speak of separation. When will you finally stop tormenting me?” Rumours began to circulate that Sophia Dorothea was no longer able to have children. This could have been one of the reasons her father-in-law decided to marry again that year. His new wife and the new Queen was Sophia Louise of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Just after the wedding, he was informed that Sophia Dorothea was pregnant again, and he lamented the fact that he had married again. The following year, she gave birth to a daughter named Friedrike Wilhelmine – to the great disappointment of the court. On 16 August 1710, she gave birth to a boy once more, but he too died before his first birthday. On 24 January 1712, she gave birth to a son who lived – the future Frederick the Great. Her father-in-law was reportedly in tears after hearing of the birth. Just a few months later, the proud mother reported to her husband that little Fritz had just had his first tooth. Although her marriage was still bad, she was slowly regaining her position, and she would soon find herself back as the first lady of the land.

Her father-in-law, King Frederick I of Prussia, died on 25 February 1713, and his widow fell into a deep depression to such an extent that she was considered to have gone insane. She was sent back to her family. Sophia Dorothea was now Queen and the first lady of the land. On 5 May 1713, Sophia Dorothea gave birth to her fifth child, a daughter named Charlotte Albertine, who would tragically die shortly after her first birthday. By then, Sophia Dorothea was already pregnant with her sixth child, another daughter – named Frederica Louise – was born on 28 September 1714. Her seventh child – a daughter named Philippine Charlotte – was born on 13 March 1716. Seven more children would follow: Louis Charles William (born 2 May 1717 – died young), her namesake Sophia Dorothea (born 25 January 1719), Louisa Ulrika (born 24 July 1720), Augustus William (born 9 August 1722), Anna Amalia (born 9 November 1723), Henry (born 18 January 1726) and Augustus Ferdinand (born 23 May 1730). She had a grand total of 14 children, of which four died young. Frederica Louise would later describe her mother as having had “a good, generous, and benevolent heart,” despite her husband’s many angry outbursts and the unhappy state of her marriage.1

Part two coming soon.

The post Sophia Dorothea of Hanover – The Olympia of the Hohenzollerns (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 1, 2019

Waiting in style – The Royal Waiting Rooms at Baarn

Royals should always travel in style, and so they should also be able to wait in style. The Dutch Railways has several royal waiting rooms, including at Amsterdam Central and The Hague HS. The city of Baarn wasn’t a royal destination but it was the gateway to Soestdijk Palace. This waiting room was presumably design by L. van Gendt who also helped to design Amsterdam Central Station. Prince Henry – brother of King William III of the Netherlands and husband of Amalia of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach and Marie of Prussia – originally wanted to have a station right by Soestdijk but the King himself did not have a station at his own palace and so his brother – a mere prince – could not have one for his palace. And so, the royal waiting rooms were installed at Baarn.

Click to view slideshow.

The waiting room has two rooms, a smaller room with a toilet and a large salon. The Dutch Railways now owns the waiting rooms and has restored them to their former glory. On the ceiling, several layers of paints have been exposed to show how the rooms must have looked over the years.

The waiting rooms are, however, only open for viewing on certain days. The likeliness of the rooms at Baarn being used has gone up a bit since Princess Beatrix now lives nearby.

The post Waiting in style – The Royal Waiting Rooms at Baarn appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 30, 2019

Victoria & Albert: Our Lives in Watercolour Book Review

Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert were enthusiastic patrons of watercolour painting. They were also avid practitioners. They eventually had a collection of thousands of paintings, including many that illustrated scenes from their own life.

The Victoria & Albert: Our Lives in Watercolour book accompanies a travelling exhibition, which I have not had the pleasure of seeing. The book is a beautiful hardcover with many of the watercolour paintings done of Queen Victoria’s life. There are a few examples of paintings done by Queen Victoria, which are also lovely. The book leads you through her life and her travels. One of my favourite paintings is the one done by Egron Sellif Lundgren of the wedding of the Princess Royal to Prince Frederick William of Prussia. The colours are simply gorgeous.

RCIN 919928 (public domain)

RCIN 919928 (public domain)I would highly recommend this lovely look at Queen Victoria’s life and travels if only to see the Queen’s own attempt at watercolour paintings. Victoria & Albert: Our Lives in Watercolour is available now in both the UK and the US. Read more about the exhibition here.

The post Victoria & Albert: Our Lives in Watercolour Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.