Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 195

December 28, 2019

Royal portraits by Johann Friedrich August Tischbein

Johann Friedrich August Tischbein was a German painter from the Tischbein family. His father was Johann Valentin Tischbein. He was appointed court painter to Friedrich Karl August, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont and also made several trips to The Netherlands. In 1795, he was hired by Leopold III, Duke of Anhalt-Dessau but left a year later to become an independent portrait painter. The Rijksmuseum Twenthe currently has an exhibition dedicated to Tischbein (the son) which had plenty of royal portraits.

The Tischbeins did several portraits of the Orange-Nassau family, including my favourite family painting (done by Anton Wilhelm Tischbein – the uncle of Johann Friedrich August) of Carolina of Orange-Nassau – about whom I wrote a book – which she gifted to her husband for his birthday. Unfortunately, that particular painting was not at this exhibition, but several of her children were. Of this exhibition, I think my favourite is the painting of Stéphanie de Beauharnais, Grand Duchess of Baden, and her daughter Louise.

Click to view slideshow.

The Tischbein exhibition at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe will run until 19 January 2020. Click here for more information.

The post Royal portraits by Johann Friedrich August Tischbein appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 27, 2019

Allene Tew – The American Princess who conquered the continent (Part two)

More of her family would die in the next years. Her mother passed away in 1923, followed by her father in 1925 and Allene took care of both of them in the last months of their life. She and Anson made a new start, and they bought a new house on Park Avenue. She had inherited the Hostetter millions from her children and now had plenty to spare. So, they also bought a house in Paris. On 22 January 1927, Anson went to have lunch with a good friend and never returned home. The official cause of death was acute indigestion, but it was probably a heart attack. The New York Times wrote that Allene was “the richest and saddest of New York’s socially celebrated widows.” Later that year, Allene set off for Europe – alone.

She bought a new house in Paris, not wanting to live in the one that she and Anson had bought together. Just a few months later, she met a handsome diplomat from the German Embassy, and his name was Prince Heinrich XXXIII Reuss of Köstritz. Thirty-three also happened to be Allene’s lucky number. He was once considered to be a possible heir to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands until the birth her daughter Juliana as he was a great-grandson of King William II of the Netherlands, through his daughter Princess Sophie. He had had two children with his first wife Princess Victoria Margaret of Prussia, but they had divorced in 1922. They were married on 10 April 1929 in her Paris home, and Allene became a Princess.

Embed from Getty Images

However, if Allene hoped for a brand-new family, she would be disappointed. Heinrich’s extended family thought she was beneath them and continued to speak German in her presence. Heinrich’s 14-year-old daughter Maria Louise wanted absolutely nothing to do with her new stepmother. His son was kinder to her. Then, a stock market crash caused Allene’s fortunes to fall, and she put her two homes in America on the market. In 1932, Allene’s second husband killed himself after losing his entire fortune. However, Allene was an experienced businesswoman by now, and she managed to economise. For Heinrich, Allene’s main attraction vanished under the sun, and it was all just too much for him. He turned to drinking and gambling and eventually, the Nazis. In 1935, Allene’s secretary announced their separation.

Allene quickly began to appear with a new man by her side. She had met him through one of her husband’s neighbours, Armgard zu Lippe-Biesterfield (the mother of Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld, the future consort of Queen Juliana of the Netherlands) and his name was Pavel (or Paul) Pavlovitch Kotzebue, a Russian Count. On 31 October 1935, Allene divorced Heinrich, and her marriage to Paul followed on 4 March 1936. Maury Paul – an American journalist – wrote, “There is something of a perennial Cinderella about the Countess Kotzebue.”

Allene would later lend money to Prince Bernhard so that he could go to the Olympic Winter Games in order to woo the then Princess Juliana. A correspondence began between them and in the first letter he recounted to her the wedding of his “aunt” Allene to Paul. Allene would later join Bernhard during the marriage negotiations and on 7 January 1937, she was present for their wedding. Apparently, her tiara had hurt her head to such an extent that she took it off during dinner and laid it on the table. Shortly after the honeymoon, Allene took it upon herself to give the future Queen a – in her opinion anyway – much-needed make-over. When the future Queen Beatrix was born in 1938, Allene was asked to become one of the five godparents.

In December 1939, as the Second World War loomed, Allene and Paul travelled back to New York where Allene was once more the owner of a grand 18-room apartment. The family kept in touch with Princess Juliana and her children who were now in exile in Canada. She also kept in touch with her stepson who – due to his royal title – had been banned from serving and was now living with his sister and her daughter in increasingly difficult circumstances in Germany. She would call him her “son” and wrote to him every three days. She would do all she could to get him to America but Maria Louise – who had always held her in contempt – was ignored. She was finally able to embrace him again in March 1948 in New York. After the war, Allene and Paul were able to return to France, though their properties had been plundered.

In 1948, Allene was one of the honoured guests at the inauguration of Princess Juliana as Queen of the Netherlands. She wrote to her stepson, “Everyone is extremely nice to me, and I was given same rank and courtesy, and attention as the Royalties here and they were very charming as well.”

Allene died in France on 1 May 1955, at the age of 82.1

The post Allene Tew – The American Princess who conquered the continent (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 26, 2019

Allene Tew – The American Princess who conquered the continent (Part one)

Allene Tew was born on 7 July 1872 in Janesville, Wisconsin as the daughter of Charles Henry Tew – a banker – and Janet Smith. She would be their only child, and shortly after her birth, the family returned to Jamestown. She had a great love of her horses. Her parents soon realised that Allene was a free spirit and she longed to see the world outside of Jamestown.

Allene became pregnant by Theodore R. Hostetter – also known as Tod – in 1891. She was considered to be of a lower class than him as he was fabulously wealthy, and his mother was not amused. Nevertheless, Allene and Tod eloped to New York, where they were married on 14 May 1891. Just a few days later, the newlyweds were on their way to Pittsburgh. Their new home would have eight servants, and Allene received an icy reception. Their daughter – named Greta – was born on 27 September 1891. The society continued to shun Allene and now her daughter too, and she was kept in total social isolation. Allene attempted to get some respectability by joining the Pittsburgh branch of the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1892. Her application was accepted though she would later be struck off when they found out that one of her listed ancestors did not exist. But for now, Allene had made her move, and she was also soon pregnant with her second child.

Their second daughter Verna was born in 1893. Tragically, young Verna would die in 1895 on her elder sister fourth birthday. Although Allene remained levelheaded and accepted her daughter’s death – more than half of children died before their fifth birthday at this time – for her husband, it seemed to be a breaking point. He had been addicted to gambling, had buried two elder brothers and now had to bury his daughter. A son was born to them on 2 October 1897, and he was named Theodore after his father. Todd continued to gamble as Allene worried about him. In 1901, Tod bought a new yacht, and that summer Allene and their children joined him on it. However, he spent most of his time below deck playing roulette. Allene took her children off the yacht and went to her parents-in-law, leaving Tod behind. The following year, Todd fell ill with pneumonia, and he played poker almost to the last. He died on 3 August 1902 – still only 32 years old. After Tod’s funeral, Allene took her two children to New York, leaving Pittsburgh behind her.

Her children had inherited whatever Tod had not gambled away, but Allene inherited nothing. So, she soon settled on a new husband by the name of Morton Nichols, a stockbroker. They were married on 27 December 1904 in London. Once shunned for being from the wrong social class, her brand new husband immediately launched her into the right circles. Shortly after the death of Morton’s father, he began planning a lengthy world tour with his family and his inherited millions. Allene embraced the trip, and they did not return home until February 1906. By then, their marriage was on the rocks, and they were rarely seen together. By 1909, they were divorced, and when Morton intended to remarry in 1911, Allene returned to using the Hostetter name.

This time, she came out of it a much richer woman. She had seven servants and owned three houses of which two were being rented out. Her children were even richer, though their funds were managed by their uncle. Allene promptly left for Europe with her daughter, hoping to marry her into the aristocracy. Little did she know that it would lead to her own third marriage. His name was Anson Wood Burchard, and he was everything her first two husbands weren’t. They were married in December 1912. Greta returned home to spend Christmas with her brother who was at a boarding school in Boston while Anson and Allene celebrated their honeymoon in London.

Allene was happy in her third marriage, and her niece would later say that Anson “was the one.” In the end, Greta brought home a man from Pittsburgh named Glenn Stewart – the only son of a self-made millionaire. He had been left disfigured when a handmade bomb had exploded in his face. They were married on 21 October 1914, the same year the First World War broke out. Allene’s son signed up as a pilot in 1917, and he died during a mission in September 1918. More tragedy was to come. Greta had miscarried her first child in 1917 but had become pregnant with twins the following year. In October 1918, Greta fell ill with influenza, and she died on 16 October 1918. Her twins did not survive. On the evening of her daughter’s funeral, Allene received the news of her son’s ill-fated mission and his fate. In one fell swoop, she had lost both her children and two grandchildren. Allene would rarely speak of the children she had lost.1

Part two coming soon.

The post Allene Tew – The American Princess who conquered the continent (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 25, 2019

Catherine of York – The Queen’s Sister

Catherine of York was born on 14 August 1479 at Eltham Palace as the daughter of King Edward IV of England and Elizabeth Woodville. She was christened at Eltham Palace, and a nurse named Joanna Colson was appointed for her. Just two weeks after her birth, her father opened negotiations for her to marry John, Prince of Asturias – the ill-fated heir of Queen Isabella I of Castile. James Butler, Earl of Ormond, was also considered. Catherine was the couple’s ninth child and sixth daughter. The following year a daughter named Bridget completed the family.

Catherine would never get to know several of her siblings. Her elder brother George had died in March 1479, Mary died on 23 May 1482, Margaret died on 11 December 1472, and it is unlikely she had any memories of her two elders brothers, the Princes in the Tower, Edward and Richard who disappeared in 1483. Her father died in 1483 when Catherine was only three. The following situation – in which her uncle Richard seized power and succeeded his brother over Catherine’s brother Edward – left Catherine in a precarious situation. Catherine’s mother was no fool and took sanctuary at Westminster Abbey with her five daughters (Elizabeth, Catherine, Cecily, Anne and Bridget) and her youngest son Richard. Elizabeth was eventually forced to surrender her younger son to his uncle, leaving her with just her daughters in sanctuary. When the marriage of Elizabeth Woodville and Edward IV was declared void upon the basis that Edward had been contracted to another woman – the girls suddenly found themselves illegitimate.

(public domain)

(public domain)On 1 March 1484, Elizabeth and her daughters came out of sanctuary after Richard publicly swore an oath that her daughters would not be harmed. The girls were “very honourably entertained and with all princely kindness.” They were probably sent to live in Queen Anne‘s household, at least for a while, before returning to their mother. Their exact whereabouts around this time are unknown.

Elizabeth soon allied herself with Margaret Beaufort and her son Henry Tudor and Catherine’s elder sister Elizabeth was promised to him. Henry invaded in 1485 and overthrew Richard – becoming King Henry VII. Catherine’s sister Elizabeth became Queen of England when they were married on 18 January 1486. Henry arranged for his mother to be given the “keeping and guiding of the ladies daughter of King Edward IV” and the sisters probably joined the household in London. Elizabeth Woodville and her daughters were restored to their rightful status, “estate, dignity, preeminence and name.” Elizabeth supported her unmarried sisters with an annuity of £50, and when they married, she gave their husbands annuities of £120. When Elizabeth was close to giving birth to her first son, her mother, sisters and Margaret Beaufort joined her. Catherine’s elder sisters were involved in the christening of the newborn Prince Arthur, but Catherine was probably too young to join in.

In 1487, Elizabeth Woodville retired to Bermondsey Abbey and around this time Bridget was dedicated to the religious life. Cecily had been married to Ralph Scrope of Upsall, but King Henry had that marriage annulled so that she could marry John Welles, 1st Viscount Welles, a staunch Lancastrian nobleman. He was also Margaret Beaufort’s half-brother. Cecily had served in the Queen’s household until her marriage when she was replaced by Anne. When Elizabeth Woodville died in 1492, Catherine was present for the Requiem Mass.

In 1495, Henry arranged the marriages of Anne and Catherine. On 4 February 1495, Anne was married to Lord Thomas Howard, the son of the Earl of Surrey with Henry giving the bride away himself. Later in 1495, at least by October, Catherine was married to Lord William Courtenay. After the wedding, Catherine would reside mainly at the castles of Tiverton, Colcombe and Powderham or her husband’s London home. Catherine gave birth to three children in quick succession: Henry (later 1st Marquess of Exeter – born 1496), Edward (born 1497 – died young) and Margaret (born 1499).

In 1500, King Henry summoned Catherine and her husband to court and, once settled into their London, they were often seen at court. Catherine must have been pleased to be near her sister again. Catherine was present when her nephew Prince Arthur married Catherine of Aragon in 1501, and she was also present at the ceremony of betrothal between her niece Margaret and King James IV of Scotland.

Catherine and her husband fell from favour the following year when it turned out that William had dined with Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk, a Yorkist claimant, and had also corresponded with him before fleeing to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor. He was suspected of inviting him to invade England. In late February William was suddenly seized and imprisoned in the Tower on charges of conspiracy. He was attainted for treason in 1503, and his estates were given to his father, and upon his father’s death, they would revert to the Crown. Catherine suddenly saw her entire future go up in flames, her children had been disinherited, and she was suddenly impoverished. For some reason, Henry did not put his brother-in-law to death, but Catherine had no way of knowing that at the time and she was probably desperately worried. Her sister Elizabeth supported her emotionally and financially during this time. Elizabeth had the Courtenay children brought to Devon even before their father’s arrest and established them with a governess, Margaret, Lady Cotton. Elizabeth also ordered warm clothing for William. Later that year, as William languished in the Tower, Catherine joined her sister on a solo progress.

In early 1503, Catherine and Elizabeth returned to London to spend Candlemas with Henry at the Tower. After the death of Prince Arthur in 1502, Elizabeth had conceived again, and she was in the late stages of pregnancy. Elizabeth was still at the Tower when her baby arrived early on 2 February. It was a difficult birth, and Catherine was in attendance. The baby was named Catherine, possibly for her aunt. Just one week later, Elizabeth became ill, and she quickly deteriorated. She died on 11 February – her 37th birthday. Catherine acted as chief mourner at her sister’s funeral, and she must have been much grieved at her sister’s death. After the service, Catherine presided over a supper at which fish was served. The following morning, Catherine and her surviving sisters assembled in Westminster Abbey where The Mass of the Trinity was celebrated. Afterwards, Catherine was among the 20 ladies who presented 37 palls of blue, red, and green cloth of gold, one for each year of Elizabeth’s life. Elizabeth’s sister each presented five palls.

After Elizabeth’s death, Catherine and her children were sent home to Tiverton where she lived as a dependent of her father-in-law. Her husband would remain in the Tower until the death of King Henry VII in 1509. He lived out his last years in freedom – dying in 1511. Catherine took a vow of perpetual chastity after her husband’s death. In 1516, Catherine was asked to be godmother to the future Queen Mary I. She lived out her last years in quiet and died in November 1527 at Tiverton Castle. She was buried in the Tiverton parish church, but her tomb has not survived. She would be the last of the York sisters to die.1

The post Catherine of York – The Queen’s Sister appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 24, 2019

Queen Victoria & Victorian Era Christmas Traditions

As we prepare to celebrate Christmas around the world in our own ways, here at History of Royal Women, we are also finishing up our Year of Queen Victoria which has been a fantastic series to write for all involved! During this series, we have shared a staggering 75 articles and over 70 journal entries and letters.

At this time of year, we are used to seeing many festive items, singing particular songs and eating certain foods which all carry feelings of tradition and nostalgia. It is therefore fitting, to round off our year of Queen Victoria by looking at where a few British Christmas traditions come from, as many stem from the Queen and Prince Albert’s love of Christmas and from the German customs of their families.

As a child, a young Victoria spent her Christmases with her mother and close family, often at Kensington Palace. The Palace was filled with decorations such as Christmas trees; this German tradition was first upheld in England by Victoria’s grandmother Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. In those days a Christmas tree was decorated with nuts, fruits and maybe a few candles and toys. Once Victoria had become Queen herself, her husband Prince Albert continued this tradition and imported yew and fir trees from his homeland which were brought inside and decorated.

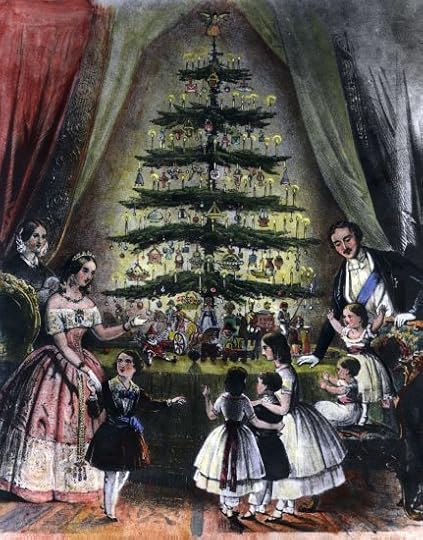

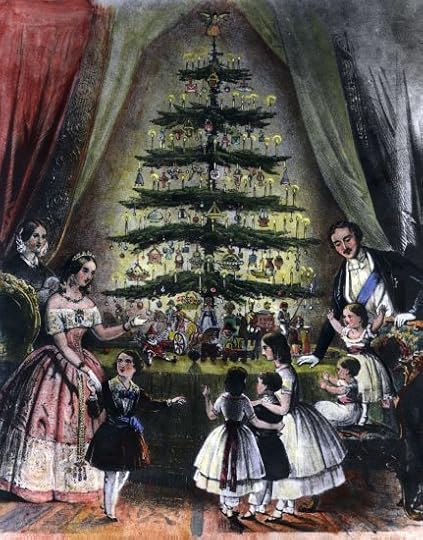

Queen Victoria did not have many happy Christmas memories from her childhood, whereas Albert loved to celebrate Christmas and eventually Victoria found love for it too. Today we often think of Albert as being the one who made the Christmas tree popular in the United Kingdom as he filled Windsor palace with them and this soon spread throughout the land. In 1848, an image of the royals around their Christmas tree was published in The Illustrated London News. Within a few years of this, the Christmas tree had become part of Christmas for many people, and as time went on, they were decorated with colourful barley sugar sweets, gingerbread and little ornaments as well as lit up by candles.

(public domain)

(public domain)It is not only the tradition of the Christmas tree that we have gained from the Victorian era, for example, Father Christmas before the Victorian era was part of English Folklore but had been much erased by the puritans in the 17th-century. Even after this, he was known as a figure of merry-making and feasting but just for adults. It was in the middle of Victoria’s reign that American and European traditions combined to create the idea of the Father Christmas or Santa Claus we know now as a bringer of gifts to children, this added a sense of magic to the old Pagan and Christian traditions of the season. The idea of Santa made Christmas more of a fun time to spend time with family, and for the first time, many people were even allowed two days off work to celebrate which meant there was more time for merriment and preparing delicious foods.

The foods enjoyed at Christmas changed as Victoria’s reign went on; in the earlier years in the north, people often ate roast beef for Christmas, and in the south they enjoyed goose. After being made popular by the royals and in fiction, however, by the end of the century, it was the turkey that sat on most Christmas tables. The poor were even able to save throughout the year by putting pennies aside with a goose club or a turkey club, and those without an oven at home would use the services of a local baker.

The industrialisation in the Victorian era is also to thank for the spread of Christmas ideas; due to the increase of factory labour and the circulation of printed news, ideas could spread faster, and certain items became cheaper to make. For middle-class families, this meant they could now purchase books and toys for their children for Christmas, whereas poorer children would get a small stocking containing an orange and nuts which was a great treat at the time. When postage costs were lowered in 1840, this also led to a new Christmas development which we now take for granted; the Christmas card. By 1870, once halfpenny post had been introduced and many more people were able to read and write, the sending of Christmas cards became an established tradition even for those who were less well off.

In 1846, another Victorian Christmas novelty was invented, just after the Christmas card. The Christmas cracker was created by Tom Smith, who was a confectioner, and the idea came from him wrapping his sweets in colourful packaging. This went on to him adding little paper hats, toys and a love note which people were thrilled by. Today we like our crackers with a joke inside and an added bang but the same excitement is still felt.

Of course, even with all of these new inventions and cheaper goods, there were always people who struggled at Christmas and were excluded from celebrations. Charles Dickens famously wrote about the plight of those in need in his beloved A Christmas Carol which was written in 1843. It was this work and reports by philanthropists that prompted the middle classes to give to charity and offer goodwill to all men during the festive period, a loving tradition which carries on to this day. Mr Dickens is also remembered as the inventor of the idea of the ‘white Christmas’, and this longing for a snowy Christmas still continues even though a cold December is not as common as it once was!

So, this Christmas Day when you open Christmas cards and gifts, pull a Christmas cracker, tuck into your meal, gaze at your Christmas tree and listen to traditional carols you can think back on how the Victorian era gave us many of these customs!

We hope you have enjoyed The Year of Queen Victoria and all of the other articles written this year by Moniek and the team at History of Royal Women. Merry Christmas and a happy new year to all who celebrate it, from Moniek, Brittani, Amy, Carabeth and all our other guest contributors.

The post Queen Victoria & Victorian Era Christmas Traditions appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of Queen Victoria – Victorian Era Christmas Traditions

As we prepare to celebrate Christmas around the world in our own ways, here at History of Royal Women, we are also finishing up our Year of Queen Victoria which has been a fantastic series to write for all involved! During this series, we have shared a staggering 75 articles and over 70 journal entries and letters.

At this time of year, we are used to seeing many festive items, singing particular songs and eating certain foods which all carry feelings of tradition and nostalgia. It is therefore fitting, to round off our year of Queen Victoria by looking at where a few British Christmas traditions come from, as many stem from the Queen and Prince Albert’s love of Christmas and from the German customs of their families.

As a child, a young Victoria spent her Christmases with her mother and close family, often at Kensington Palace. The Palace was filled with decorations such as Christmas trees; this German tradition was first upheld in England by Victoria’s grandmother Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. In those days a Christmas tree was decorated with nuts, fruits and maybe a few candles and toys. Once Victoria had become Queen herself, her husband Prince Albert continued this tradition and imported yew and fir trees from his homeland which were brought inside and decorated.

Queen Victoria did not have many happy Christmas memories from her childhood, whereas Albert loved to celebrate Christmas and eventually Victoria found love for it too. Today we often think of Albert as being the one who made the Christmas tree popular in the United Kingdom as he filled Windsor palace with them and this soon spread throughout the land. In 1848, an image of the royals around their Christmas tree was published in The Illustrated London News. Within a few years of this, the Christmas tree had become part of Christmas for many people, and as time went on, they were decorated with colourful barley sugar sweets, gingerbread and little ornaments as well as lit up by candles.

(public domain)

(public domain)It is not only the tradition of the Christmas tree that we have gained from the Victorian era, for example, Father Christmas before the Victorian era was part of English Folklore but had been much erased by the puritans in the 17th-century. Even after this, he was known as a figure of merry-making and feasting but just for adults. It was in the middle of Victoria’s reign that American and European traditions combined to create the idea of the Father Christmas or Santa Claus we know now as a bringer of gifts to children, this added a sense of magic to the old Pagan and Christian traditions of the season. The idea of Santa made Christmas more of a fun time to spend time with family, and for the first time, many people were even allowed two days off work to celebrate which meant there was more time for merriment and preparing delicious foods.

The foods enjoyed at Christmas changed as Victoria’s reign went on; in the earlier years in the north, people often ate roast beef for Christmas, and in the south they enjoyed goose. After being made popular by the royals and in fiction, however, by the end of the century, it was the turkey that sat on most Christmas tables. The poor were even able to save throughout the year by putting pennies aside with a goose club or a turkey club, and those without an oven at home would use the services of a local baker.

The industrialisation in the Victorian era is also to thank for the spread of Christmas ideas; due to the increase of factory labour and the circulation of printed news, ideas could spread faster, and certain items became cheaper to make. For middle-class families, this meant they could now purchase books and toys for their children for Christmas, whereas poorer children would get a small stocking containing an orange and nuts which was a great treat at the time. When postage costs were lowered in 1840, this also led to a new Christmas development which we now take for granted; the Christmas card. By 1870, once halfpenny post had been introduced and many more people were able to read and write, the sending of Christmas cards became an established tradition even for those who were less well off.

In 1846, another Victorian Christmas novelty was invented, just after the Christmas card. The Christmas cracker was created by Tom Smith, who was a confectioner, and the idea came from him wrapping his sweets in colourful packaging. This went on to him adding little paper hats, toys and a love note which people were thrilled by. Today we like our crackers with a joke inside and an added bang but the same excitement is still felt.

Of course, even with all of these new inventions and cheaper goods, there were always people who struggled at Christmas and were excluded from celebrations. Charles Dickens famously wrote about the plight of those in need in his beloved A Christmas Carol which was written in 1843. It was this work and reports by philanthropists that prompted the middle classes to give to charity and offer goodwill to all men during the festive period, a loving tradition which carries on to this day. Mr Dickens is also remembered as the inventor of the idea of the ‘white Christmas’, and this longing for a snowy Christmas still continues even though a cold December is not as common as it once was!

So, this Christmas Day when you open Christmas cards and gifts, pull a Christmas cracker, tuck into your meal, gaze at your Christmas tree and listen to traditional carols you can think back on how the Victorian era gave us many of these customs!

We hope you have enjoyed The Year of Queen Victoria and all of the other articles written this year by Moniek and the team at History of Royal Women. Merry Christmas and a happy new year to all who celebrate it, from Moniek, Brittani, Amy, Carabeth and all our other guest contributors.

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – Victorian Era Christmas Traditions appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 23, 2019

Will the Duchess of Cambridge ever be Duchess of Cornwall?

The current Duchess of Cornwall is, of course, Camilla. She is the wife of the Prince of Wales and as such is also legally the Princess of Wales. However, out of respect for the previous Princess of Wales, Diana, she chooses not to use the title.

But will the Duchess of Cambridge ever be known as the Duchess of Cornwall? The short answer is yes unless her husband William predeceases his father before Charles becomes King. When Queen Elizabeth II passes away, Charles will automatically become King and Camilla will be Queen consort. The Duke of Cornwall title will automatically pass to William unlike the Prince of Wales title, which needs to be invested.

As such, from Prince Charles’s accession until the day William is created Prince of Wales by his father, William and Catherine will be known as The Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and Cambridge. After he is created Prince of Wales, that title must take precedence and from then on they will be known as the Prince and Princess of Wales.

Do you have a question that you would like to submit to History of Royal Women? Email us at info@historyofroyalwomen.com or fill in our contact form here.

The post Will the Duchess of Cambridge ever be Duchess of Cornwall? appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 22, 2019

Queen Victoria & The Regency Act 1830

Queen (then Princess) Victoria was born in the early hours (4.15 am) of 24 May 1819. At the time of her birth, the future queen was fifth in line to the throne after King George III’s four elder sons: the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York, the Duke of Clarence, and the Duke of Kent. Her uncles either had no legitimate children (anymore) or children who died in infancy, meaning she was the only royal of her generation.

The United Kingdom was in a succession crisis at the time due to the death of Princess Charlotte (daughter to the Prince of Wales and Victoria’s first cousin). Her uncle, the Duke of Clarence, succeeded his elder brother King George IV on 26 June 1830, becoming King William IV. At the time, Victoria was only 11 years old. Naturally, due to Victoria’s young age, there were fears that if King William IV died before she turned 18, there would have to be a regency put into place.

This was to be in the form of Victoria’s mother, the Duchess of Kent. The Regency Act 1830 set out plans for the Duchess to act as regent until Victoria came of age, but the King admitted he did not trust the Duchess’s (born Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld) ability to act as regent. His Majesty even declared, in front of the Duchess of Kent, that he hoped to live until Victoria was 18 so that she would never have to serve as regent.

The Regency Act not only set forth who would be regent if Victoria was to come to the throne underage, but it also had provisions for if the King ever had any legitimate children who could come to the throne before they turned 18. In that case, the King’s wife, Queen Adelaide, would serve as regent for her child until they turned 18. It also stated that if William died while Adelaide was pregnant, Victoria would be monarch until the child was born. The child would automatically replace Victoria upon its birth.

Both the Duchess of Kent and Queen Adelaide would have the ability to exercise all powers of the monarchy as regent. However, they were prohibited from giving royal assent to bills that would change the line of succession. They were also banned from giving royal assent to bills that would revoke or alter the Protestant Religion and Presbyterian Church Act 1707 and the Act of Uniformity 1662.

If the underage monarch wanted to marry, they had to be given permission by the regent. If someone married the monarch without permission of the regent, they would be guilty of high reason. Anyone who helped arrange the marriage would also be guilty. The regent was also barred from marrying a Roman Catholic. If they chose to marry a Roman Catholic, a foreigner without permission, or even left the United Kingdom without permission, the regent would lose their status as regent.

It was given royal assent on 23 December 1830.

Thankfully, the Regency Act of 1830 would never have to be used, as King William IV wouldn’t die until after Victoria reached the age of majority in 1837.

The post Queen Victoria & The Regency Act 1830 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of Queen Victoria – The Regency Act 1830

Queen (then Princess) Victoria was born in the early hours (4.15 am) of 24 May 1819. At the time of her birth, the future queen was fifth in line to the throne after King George III’s four elder sons: the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York, the Duke of Clarence, and the Duke of Kent. Her uncles either had no legitimate children (anymore) or children who died in infancy, meaning she was the only royal of her generation.

The United Kingdom was in a succession crisis at the time due to the death of Princess Charlotte (daughter to the Prince of Wales and Victoria’s first cousin). Her uncle, the Duke of Clarence, succeeded his elder brother King George IV on 26 June 1830, becoming King William IV. At the time, Victoria was only 11 years old. Naturally, due to Victoria’s young age, there were fears that if King William IV died before she turned 18, there would have to be a regency put into place.

This was to be in the form of Victoria’s mother, the Duchess of Kent. The Regency Act 1830 set out plans for the Duchess to act as regent until Victoria came of age, but the King admitted he did not trust the Duchess’s (born Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld) ability to act as regent. His Majesty even declared, in front of the Duchess of Kent, that he hoped to live until Victoria was 18 so that she would never have to serve as regent.

The Regency Act not only set forth who would be regent if Victoria was to come to the throne underage, but it also had provisions for if the King ever had any legitimate children who could come to the throne before they turned 18. In that case, the King’s wife, Queen Adelaide, would serve as regent for her child until they turned 18. It also stated that if William died while Adelaide was pregnant, Victoria would be monarch until the child was born. The child would automatically replace Victoria upon its birth.

Both the Duchess of Kent and Queen Adelaide would have the ability to exercise all powers of the monarchy as regent. However, they were prohibited from giving royal assent to bills that would change the line of succession. They were also banned from giving royal assent to bills that would revoke or alter the Protestant Religion and Presbyterian Church Act 1707 and the Act of Uniformity 1662.

If the underage monarch wanted to marry, they had to be given permission by the regent. If someone married the monarch without permission of the regent, they would be guilty of high reason. Anyone who helped arrange the marriage would also be guilty. The regent was also barred from marrying a Roman Catholic. If they chose to marry a Roman Catholic, a foreigner without permission, or even left the United Kingdom without permission, the regent would lose their status as regent.

It was given royal assent on 23 December 1830.

Thankfully, the Regency Act of 1830 would never have to be used, as King William IV wouldn’t die until after Victoria reached the age of majority in 1837.

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – The Regency Act 1830 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 21, 2019

Louise, Princess Royal – Duchess of Fife (Part two)

On 22 January 1901, Queen Victoria died and was succeeded by Louise’s father who now became King Edward VII. Her elder brother George was invested as Prince of Wales – Prince Albert Victor had died in 1892. On 9 November 1905, Louise was created Princess Royal by her father. The previous Princess Royal – the eldest daughter of Queen Victoria who was also known as the Empress Frederick – had died in 1901. Louise’s daughter also received additional honours. As daughters of a Duke, they were as Lady Maud and Lady Alexandra, but King Edward VII conferred the style and title of “Princess” and “Highness” on them. In 1900, Queen Victoria had granted Louise’s husband a new patent creating him Duke of Fife and Earl of Macduff with the proviso that in default of male heirs, these titles could pass to his daughters and their male issue. Princess Alexandra now stood to inherit the Dukedom.

In 1910, King Edward VII passed away, and Louise’s brother George became King George V. That same year, Louise’s eldest daughter Alexandra had secretly become engaged to Prince Christopher of Greece, the youngest son of King George I of the Hellenes. This engagement was broken off when the family found out about it. The following year, the entire Fife family went on a trip to Egypt and Sudan. In November 1911, they boarded the Delhi at Tilbury. They were battered by storms on the way and were blown into a sandbank on the Moroccan coast. Louise had told her husband, “If we are to be drowned, we will be drowned together.”1 Several ships were already on their way for a rescue operation when the Delhi had failed to appear on time. Louise and her husband refused to leave until all the women and children had been rescued and were among the last to leave. During the rescue, Louise lost her jewel case and both Alexandra and Maud were thrown into the sea by a large wave. The family was soaked to the bone and had lost most of their belongings, but they were alive.

Her husband later wrote, “I thought some of us if not all must have drowned! Yet one had to appear perfectly calm! If I live twenty years, the memory of that night and day will live with me. I am relieved to say that the Princess Royal is fairly well though I think she is beginning to feel the reaction now – she and our children were wonderfully brave! I may add that in my opinion nothing but our excellent life belts saved us and of course the hand of Almighty God.”2 A few weeks later, he became ill with pleurisy. Their personal physician was summoned from London, but he arrived too late. The Duke of Fife died on 29 January 1912 at the age of 62.

Louise’s sister Maud wrote, “How sad it all is this sudden death of poor Macduff – one cannot think of dear Louise’s grief, as fancy what a loss he is to her, she lived for him and their two children, he was her all – it seems impossible to be true, how terribly quickly it was all over, I suppose he must have been ill some time without anyone understanding it was serious.”3 Louise later wrote, “He said he would fight the illness as he fought the waves – he only wanted to wait to help me and our children – and was very tired. He was ready for Heaven and now is at Peace! Doctors, nurses, oxygen, all was done, but of no avail, he always went down, nothing on earth could hold him up. We sat by him and saw his precious life pass peacefully away. He looked like a beautiful saint.”4 The family arrived home with the Duke’s coffin at the end of February. Princess Alexandra returned to England as Duchess of Fife in her own right.

In the summer of 1913, Alexandra became engaged to her first cousin once removed Prince Arthur of Connaught. They were married on the 15 October at St. James’s Palace. Their only child and Louise’s first grandchild was born on 9 August 1914 – he was called Prince Alastair of Connaught. Louise had always preferred to live in seclusion and with the death of her husband, even more so. She briefly left her seclusion on 12 November 1923 when her youngest daughter Princess Maud married Lord Carnegie, the eldest son and heir of the Earl of Southesk. Their only son – named James – was born on 23 September 1929.

Louise’s health became a cause for concern not much later, and she complained of feeling unwell to her eldest daughter. A doctor diagnosed her with a severe gastric haemorrhage. Her health eventually improved somewhat, but it remained a source of worry for the family. She would only occasionally appear with the family and began to have heart trouble. In the autumn of 1929, Louise suffered another gastric haemorrhage, and she was brought to London. She would linger for some 15 months, spending much time in bed. In the afternoon of 4 January 1931, Louise died of a heart attack in her sleep. Her brother King George V wrote to their sister Maud, “Louise suffered so terribly these last few months that one can but thank God. She is at peace with her dear ones. But it’s sad for us, and the loss of a sister comes very near one’s heart.”5

The post Louise, Princess Royal – Duchess of Fife (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.