Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 196

December 20, 2019

Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg – Queen Victoria’s mother-in-law

Princess Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg was born on 21 December 1800 as the daughter of Augustus, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg and his first wife Louise Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Her mother never recovered from the childbirth and died just 11 days later on 4 January 1801. Her father remarried on 24 April 1802 to Karoline Amalie of Hesse-Kassel, but Louise was destined to remain an only child. Her father’s second marriage was as unhappy as his first, but despite this, Karoline Amalie was a devoted stepmother.

On 31 July 1817, Louise married the 33-year-old Ernst III, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, later Ernst I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at Gotha. Their first child, a son named for his father, was born on 21 June 1818. A second son, Prince Albert, the future consort of Queen Victoria, was born on 26 August 1819. Louise wrote gushingly of her second son to a friend, “You should see him, he is pretty like an angel, he has big blue eyes, a beautiful nose, quite a small mouth and dimples in his cheeks. He is friendly and smiles the whole time, and he is so big that a cap which Ernst wore when three months is too small for him, and he is only seven weeks yet.”1

Countess Augusta Reuss of Ebersdorf, the Dowager Duchess of Coburg-Saalfeld and Ernst’s mother, wrote to the Duchess of Kent (Queen Victoria’s mother) the following day, “The date will itself make you suspect that I am sitting by Louischen’s bed. She was yesterday morning safely and quickly delivered of a little boy. Siebold, the accoucheuse, had only been called at three, and at six the little one gave his first cry in this world and looked about like a little squirrel with a pair of large black eyes. At a quarter to seven, I heard the tramp of a horse. It was a groom who brought the joyful news. I was off directly, as you may imagine, and found the little mother slightly exhausted, but gaie et dispos (cheerfully and willing). She sends you and Edward (the Duke of Kent) a thousand kind messages.”2

(public domain)

(public domain)Louise’s stepmother extended her affections to her stepgrandsons, and they would maintain an extensive correspondence until her death. When Louise and Ernst were away in 1822, Karoline Amalie invited the boys to her home in Gotha, writing, “I need not tell you, my dearest son, that while they are with me, dear to me as they are, they would be the object of my life; not can I say how much such a mark of confidence would touch me.”3

Louise and Ernst were divorced in 1826 after she allegedly committed adultery with Lieutenant Alexander von Haustein, who was created Count Pölzig when they married later that same year. Louise never denied or admitted to the charges and wrote to a friend, “I am to separate from the Duke… We came to an understanding and parted with tears, for life.” Ernst himself had, of course, not been faithful to her either. She later wrote, “Leaving my children was the most painful thing of all.”4 In March 1831, Louise and Alexander went to see a performance at the theatre, and she fainted after suffering a haemorrhage and had to be carried out.

Louise’s stepmother wrote on 27 July 1831, “The sad state of my poor Louise bows me to the earth… The thought that her children had forgotten her distressed her very much. She wished to know if they ever spoke of her. I answered her that they were far too good to forget her; that they did not know of her sufferings, as it would grieve the good children too much.”5

Louise dictated a final message for her husband to her maid, “The feeling that my strength is sinking every hour and that perhaps this illness will end only with my death induces me to make one more request of my deeply beloved husband. If it is God’s wish to call me away in Paris, I wish my body to be taken to Germany, to my husband’s estate, in case he intends to live there in future. Should he choose another place, I beg to be taken there. I was happy to have lived by his side, but if death is going to part us, I wish my body at least to be near him.”6

She never recovered and died of uterine cancer on 30 August 1831. She had collapsed with Alexander in the next room. On 13 December 1832, she was buried in the churchyard at Pfesselbach, but she was moved 14 years later by her sons to the Ducal tomb in the Church of St Moritz in Coburg to lay by her first husband’s side in defiance of her last wishes.

After her death, Louise’s stepmother wrote to Louise’s former husband, “My dear Duke, this also I have to endure that that child whom I watched over with such loved should go before me. May God soon allow me to be reunited to all my loved ones… It is a most bitter feeling that that dear, dear house (of Gotha) is now quite extinct.”7

In 1864, Queen Victoria wrote, “The Princess is described as having been very handsome, though very small; fair with blue eyes; and Prince Albert is said to have been extremely like her. An old servant who had known her for many years told the Queen that when she first saw the Prince at Coburg in 1844, she was quite overcome by the resemblance to his mother. She was full of cleverness and talent, but the marriage was not a happy one, and a separation took place in 1824 when the young Duchess finally left Coburg and never saw her children again. She died in 1831, after a long and painful illness, in her 32nd year.”

Prince Albert, “never forgot about her, and spoke with much tenderness and sorrow of his poor mother, and was deeply affected in reading, after his marriage, the accounts of her sad and painful illness. One of the first gifts he made to the Queen was a little pin he had received from her when a little child. Princess Louise (Albert and Victoria’s fourth daughter) is said to be like her in face.”8

The post Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg – Queen Victoria’s mother-in-law appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of Queen Victoria – Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg: Queen Victoria’s mother-in-law

Princess Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg was born on 21 December 1800 as the daughter of Augustus, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg and his first wife Louise Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Her mother never recovered from the childbirth and died just 11 days later on 4 January 1801. Her father remarried on 24 April 1802 to Karoline Amalie of Hesse-Kassel, but Louise was destined to remain an only child. Her father’s second marriage was as unhappy as his first, but despite this, Karoline Amalie was a devoted stepmother.

On 31 July 1817, Louise married the 33-year-old Ernst III, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, later Ernst I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at Gotha. Their first child, a son named for his father, was born on 21 June 1818. A second son, Prince Albert, the future consort of Queen Victoria, was born on 26 August 1819. Louise wrote gushingly of her second son to a friend, “You should see him, he is pretty like an angel, he has big blue eyes, a beautiful nose, quite a small mouth and dimples in his cheeks. He is friendly and smiles the whole time, and he is so big that a cap which Ernst wore when three months is too small for him, and he is only seven weeks yet.”1

Countess Augusta Reuss of Ebersdorf, the Dowager Duchess of Coburg-Saalfeld and Ernst’s mother, wrote to the Duchess of Kent (Queen Victoria’s mother) the following day, “The date will itself make you suspect that I am sitting by Louischen’s bed. She was yesterday morning safely and quickly delivered of a little boy. Siebold, the accoucheuse, had only been called at three, and at six the little one gave his first cry in this world and looked about like a little squirrel with a pair of large black eyes. At a quarter to seven, I heard the tramp of a horse. It was a groom who brought the joyful news. I was off directly, as you may imagine, and found the little mother slightly exhausted, but gaie et dispos (cheerfully and willing). She sends you and Edward (the Duke of Kent) a thousand kind messages.”2

(public domain)

(public domain)Louise’s stepmother extended her affections to her stepgrandsons, and they would maintain an extensive correspondence until her death. When Louise and Ernst were away in 1822, Karoline Amalie invited the boys to her home in Gotha, writing, “I need not tell you, my dearest son, that while they are with me, dear to me as they are, they would be the object of my life; not can I say how much such a mark of confidence would touch me.”3

Louise and Ernst were divorced in 1826 after she allegedly committed adultery with Lieutenant Alexander von Haustein, who was created Count Pölzig when they married later that same year. Louise never denied or admitted to the charges and wrote to a friend, “I am to separate from the Duke… We came to an understanding and parted with tears, for life.” Ernst himself had, of course, not been faithful to her either. She later wrote, “Leaving my children was the most painful thing of all.”4 In March 1831, Louise and Alexander went to see a performance at the theatre, and she fainted after suffering a haemorrhage and had to be carried out.

Louise’s stepmother wrote on 27 July 1831, “The sad state of my poor Louise bows me to the earth… The thought that her children had forgotten her distressed her very much. She wished to know if they ever spoke of her. I answered her that they were far too good to forget her; that they did not know of her sufferings, as it would grieve the good children too much.”5

Louise dictated a final message for her husband to her maid, “The feeling that my strength is sinking every hour and that perhaps this illness will end only with my death induces me to make one more request of my deeply beloved husband. If it is God’s wish to call me away in Paris, I wish my body to be taken to Germany, to my husband’s estate, in case he intends to live there in future. Should he choose another place, I beg to be taken there. I was happy to have lived by his side, but if death is going to part us, I wish my body at least to be near him.”6

She never recovered and died of uterine cancer on 30 August 1831. She had collapsed with Alexander in the next room. On 13 December 1832, she was buried in the churchyard at Pfesselbach, but she was moved 14 years later by her sons to the Ducal tomb in the Church of St Moritz in Coburg to lay by her first husband’s side in defiance of her last wishes.

After her death, Louise’s stepmother wrote to Louise’s former husband, “My dear Duke, this also I have to endure that that child whom I watched over with such loved should go before me. May God soon allow me to be reunited to all my loved ones… It is a most bitter feeling that that dear, dear house (of Gotha) is now quite extinct.”7

In 1864, Queen Victoria wrote, “The Princess is described as having been very handsome, though very small; fair with blue eyes; and Prince Albert is said to have been extremely like her. An old servant who had known her for many years told the Queen that when she first saw the Prince at Coburg in 1844, she was quite overcome by the resemblance to his mother. She was full of cleverness and talent, but the marriage was not a happy one, and a separation took place in 1824 when the young Duchess finally left Coburg and never saw her children again. She died in 1831, after a long and painful illness, in her 32nd year.”

Prince Albert, “never forgot about her, and spoke with much tenderness and sorrow of his poor mother, and was deeply affected in reading, after his marriage, the accounts of her sad and painful illness. One of the first gifts he made to the Queen was a little pin he had received from her when a little child. Princess Louise (Albert and Victoria’s fourth daughter) is said to be like her in face.”8

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg: Queen Victoria’s mother-in-law appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Book News January 2020

Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen

Paperback – 15 January 2020 (UK) & 1 April 2020 (US)

Isabella of France married Edward II in January 1308, and afterwards became one of the most notorious women in English history. In 1325, she was sent to her homeland to negotiate a peace settlement between her husband and her brother Charles IV, king of France. She refused to return. Instead, she began a relationship with her husband s deadliest enemy, the English baron Roger Mortimer. With the king s son and heir, the future Edward III, under their control, the pair led an invasion of England which ultimately resulted in Edward II s forced abdication in January 1327. Isabella and Mortimer ruled England during Edward III s minority until he overthrew them in October 1330.

A rebel against her own husband and king, and regent for her son, Isabella was a powerful, capable and intelligent woman. She forced the first ever abdication of a king in England, and thus changed the course of English history. Examining Isabella s life with particular focus on her revolutionary actions in the 1320s, this book corrects the many myths surrounding her and provides a vivid account of this most fascinating and influential of women.

Four Queens and a Countess: Mary Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, Mary I, Lady Jane Grey and Bess of Hardwick: The Struggle for the Crown

Paperback – 15 September 2019 (UK) & 1 January 2020 (US)

When Mary Stuart was forced off the Scottish throne she fled to England, a move that made her cousin Queen Elizabeth very uneasy. Elizabeth had continued the religious changes made by her father and England was a Protestant country, yet ardent Catholics plotted to depose Elizabeth and put Mary Stuart on the English throne. So what was Queen Elizabeth going to do with a kingdomless queen likely to take hers?

The Other Windsor Girl: A Novel of Princess Margaret, Royal Rebel

Paperback – 5 November 2019 (US) & 23 January 2020 (UK)

Diana, Catherine, Meghan…glamorous Princess Margaret outdid them all. Springing into post-World War II society, and quite naughty and haughty, she lived in a whirlwind of fame and notoriety. Georgie Blalock captures the fascinating, fast-living princess and her “set” as seen through the eyes of one of her ladies-in-waiting.

In dreary, post-war Britain, Princess Margaret captivates everyone with her cutting edge fashion sense and biting quips. The royal socialite, cigarette holder in one hand, cocktail in the other, sparkles in the company of her glittering entourage of wealthy young aristocrats known as the Margaret Set, but her outrageous lifestyle conflicts with her place as Queen Elizabeth’s younger sister. Can she be a dutiful princess while still dazzling the world on her own terms?

Post-war Britain isn’t glamorous for The Honorable Vera Strathmore. While writing scandalous novels, she dreams of living and working in New York, and regaining the happiness she enjoyed before her fiancé was killed in the war. A chance meeting with the Princess changes her life forever. Vera amuses the princess, and what—or who—Margaret wants, Margaret gets. Soon, Vera gains Margaret’s confidence and the privileged position of second lady-in-waiting to the Princess. Thrust into the center of Margaret’s social and royal life, Vera watches the princess’s love affair with dashing Captain Peter Townsend unfurl.

But while Margaret, as a member of the Royal Family, is not free to act on her desires, Vera soon wants the freedom to pursue her own dreams. As time and Princess Margaret’s scandalous behavior progress, both women will be forced to choose between status, duty, and love…

The Diary of Lady Murasaki (Dover Thrift Editions)

Paperback – 18 December 2019 (US) & 31 January 2020 (UK)

Derived from the journals of an empress’s tutor and companion, this unique book offers rare glimpses of court life in eleventh-century Japan. Lady Murasaki recounts episodes of drama and intrigue among courtiers as well as the elaborate rituals related to the birth of a prince. Her observations, expressed with great subtlety, offer penetrating and timeless insights into human nature.

Murasaki Shikibu (circa AD 973–1025) served among the gifted poets and writers of the imperial court during the Heian period. She and other women of the era were instrumental in developing Japanese as a written language, and her masterpiece, The Tale of Genji, is regarded as the world’s first novel. Lady Murasaki’s diary reveals the role of books in her society, including the laborious copying of texts and their high status as treasured gifts. This translation is accompanied by a Foreword from American poet and Japanophile Amy Lowell.

Elizabeth Widville, Lady Grey: Edward IV’s Chief Mistress and the ‘Pink Queen’

Paperback – 30 January 2020 (UK) & 3 May 2020 (US)

Wife to Edward IV and mother to the Princes in the Tower and later Queen Elizabeth of York, Elizabeth Widville was a central figure during the War of the Roses. Much of her life is shrouded in speculation and myth – even her name, commonly spelled as Woodville’, is a hotly contested issue. Born in the turbulent fifteenth century, she was famed for her beauty and controversial second marriage to Edward IV, who she married just three years after he had displaced the Lancastrian Henry VI and claimed the English throne. As Queen Consort, Elizabeth’s rise from commoner to royalty continues to capture modern imagination. Undoubtedly, it enriched the position of her family. Her elevated position and influence invoked hostility from Richard Neville, the Kingmaker’, which later led to open discord and rebellion. Throughout her life and even after the death of her husband, Elizabeth remained politically influential: briefly proclaiming her son King Edward V of England before he was diposed by her brother-in-law, the infamous Richard III, she would later play an important role in securing the succession of Henry Tudor in 1485 and his marriage to her daughter Elizabeth of York, thus and ending the War of the Roses. Elizabeth Widville was an endlessly enigmatic historical figure, who has been obscured by dramatizations and misconceptions. In this fascinating and insightful biography, Dr John Ashdown-Hill brings shines a light on the truth of her life.

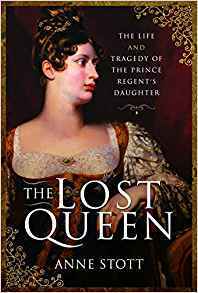

The Lost Queen: The Life & Tragedy of the Prince Regent’s Daughter

Hardcover – 30 January 2020 (UK) & 3 May 2020 (US)

As the only child of the Prince Regent and Caroline of Brunswick, Princess Charlotte of Wales (1796-1817) was the heiress presumptive to the throne. Her parents’ marriage had already broken up by the time she was born. She had a difficult childhood and a turbulent adolescence, but she was popular with the public, who looked to her to restore the good name of the monarchy. When she broke off her engagement to a Dutch prince, her father put her under virtual imprisonment and she endured a period of profound unhappiness. But she held out for the freedom to choose her husband, and when she married Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg she finally achieved contentment. Her happiness was cruelly cut short when she died in childbirth at the age of twenty-one only eighteen months later. A shocked nation went into mourning for its people’s princess’, the queen who never was.

The post Book News January 2020 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 19, 2019

Louise, Princess Royal – Duchess of Fife (Part one)

Princess Louise was born at Marlborough House on 20 February 1867 as the eldest daughter of the then Prince and Princess of Wales, later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. She had two elder siblings, Prince Albert Victor and the future King George V, and three younger siblings, Princess Victoria, Princess Maud (later Queen of Norway) and Prince Alexander John (who died young).

Her mother had been unwell since Christmas 1866, and she was eventually diagnosed with rheumatic fever. It took several urgent telegrams for her husband to return to Marlborough House. Alexandra suffered acute pains in her leg and hip and these continued even after the birth of Louise. It wasn’t until April that she was able to look out the window from a wheelchair. She would always have a limp from now on. Louise was christened on 10 May 1867, and she was known to be a sickly child. Louise accompanied her elder siblings and her mother to Egypt, stopping en route in Denmark, Germany and Austria. Louise had been named for her grandmother, Louise of Hesse-Kassel, Queen of Denmark and the family spent six weeks with Alexandra’s parents.

Louise grew up relatively care-free on the Sandringham estate. She also often visited Queen Victoria who once wrote Louise and her siblings were, “such ill-bred, ill-trained children. I can’t fancy them all.” Louise often wrote to her grandmother, such as this letter from 1 September 1887 when she was staying in St Moritz. “This is a charming place, the weather has been beautiful, and I am feeling better. We have been for several amusing expeditions, and the country is lovely. One day we climbed up a mountain, and all found some Edelweiss of which we were very proud, and I am sending you a little piece for luck, which I picked myself, and we have to go up a great height to get it. I trust that you are well and enjoying yourself in Scotland, and are having as fine weather as we are.”1

Louise and her sisters received a very indifferent education and were known to be frequently ill. They were often boisterous and held pillow fights and “unladylike pastimes.” Their mother was quite possessive of them and had once declared that none of them would marry a German Prince. She would rather that they did not marry at all.

Nevertheless, Louise became engaged when she was 22 to Alexander Duff, Earl Fife – who was a great-grandson of King William IV and his mistress Dorothea Jordan. He was a friend of the Prince of Wales and one of the few friends that Queen Victoria liked. Louise had first met him at the wedding of Princess Beatrice.

Their engagement was announced in June 1889, and it was met with some concern. Mary of Teck, a friend of Louise, wrote, “For a future Princess Royal to marry a subject seems rather strange.” Also, he was known to have a disagreeable character, and he was ill-mannered. However, Louise was perfectly happy with her future husband. For her, it was a way out, and she would not have to leave England. With both her brothers in the navy – should the worst happen – would he also make a suitable Prince Consort? The Prince of Wales waved the concerns away. Queen Victoria recorded in her journal, “Bertie, Alix and the girls came to luncheon, but they asked specially to speak to me before, and I was still on the sofa. He said he had something very important to communicate, viz. to ask my consent to his Louise’s marriage with Lord Fife! I was much pleased and readily gave my consent, and kissed her and wished her all possible happiness.”

Their wedding took place on 27 July 1889 in the private chapel at Buckingham Palace. At the wedding breakfast, Queen Victoria announced that the groom would be raised from the Earldom to a Dukedom. The honeymoon was spent at Mar Lodge and other estates in Scotland. They would eventually divide their time between Sheen Lodge – which was their favourite home – and several homes in Scotland. Marriage brought Louise out of her shell, and her family found her looking “so mischievous and happy.” She discovered a love of painting and interior design. In early 1890 Louise wrote to Queen Victoria, “I daresay you know dear Grandmama, that I do not often gush, but I cannot tell you how happy I am with Macduff. Happier than I ever thought I would be.”2

By then Louise was pregnant with her first child, but tragically their son Alastair was stillborn on 16 June 1890. A healthy daughter named Alexandra was born on 17 May 1891, and at the end of 1892, she found herself pregnant for the third time. On 3 April 1893, Lady Maud was born to them. They would have no more children, and there would be no male heir to the Dukedom.

Part two coming soon.

The post Louise, Princess Royal – Duchess of Fife (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 18, 2019

Hermine Reuss of Greiz – An Empress in Exile (Part two)

My book about Hermine Reuss of Greiz “Hermine: An Empress in Exile” will be released in 2020. Click here to stay up to date on pre-orders and the definitive release date!

Hermine decided to go see the Emperor alone, and he later wrote of their first meeting, “When I saw her, I was immediately profoundly stirred. I was fascinated. I instantly recognised that she was my mate.” Just a few days into the visit, he proposed to her. Hermine realised that she would not be able to bring all her children to live here and that her life would be severely limited by his exile.

Nevertheless, her heart said yes. She reserved the right to spend time in Germany, where the Emperor was not allowed to go by the authorities, and three of her children would stay with her. The Emperor later wrote to his friend Maximilian Egon II, Prince of Fürstenberg, “So I have found a woman’s heart, after all, a German princess, an adorable, clever young widow has decided to bring sunshine into my lonely house & to help share my solitude and make it beautiful with her warm, devoted love. Peace and happiness have taken possession of my torn, tormented heart now that she has given me her hand… My happiness knows no bounds.”

They were married on 5 November 1922 at Doorn. Still, his family was not at all happy, and the Emperor angrily wrote, “The Crown Princess is obviously furious that she is being set aside, she wanted to play the role of Empress herself.” His daughter Viktoria Luise wrote, “The fact that this woman came to Doorn with the idea of marrying the Emperor, whom she barely knew, is bad enough. Papa does not know what he is doing. His new wife will soon tire of him, of the life in Doorn and leave him.” Several family members were absent from the wedding. Still, it went ahead as usual with the Emperor’s brother Heinrich toasting, “I drink to the health of his Majesty the Emperor and King and of Her Majesty the Empress and Queen.”

Life with the Emperor in exile was one of routine. He was often outside chopping down trees, but he found joy in the presence of Hermine’s young daughter Henriette, whom he lovingly referred to as “the General.” But as expected by many, Hermine soon felt unhappy and restless. She often travelled to Silesia to care for her first husband’s estates, and when she was in Berlin, she was given the use of apartments in the Old Palace. Perhaps Hermine had fervently hoped for a restoration of the monarchy, and as Adolf Hitler rose in power, she found herself latching onto the new regime in order to lobby for it. Hermann Göring visited the exiled couple twice at Doorn and Hermine met with Adolf Hitler himself several times while in Berlin. The Emperor wrote to his aide-de-camp, “My return to the throne can not happen fast enough for her, but we won’t get there with her way. She follows the Nazis and does all she can in Berlin, and in writing from here, which does more damage than good.”

As the Second World War approached, Hermine and the Emperor suddenly found themselves in the middle of a war zone. Even a British offer of asylum could not sway him, and the Emperor said he “would rather be shot in Holland than flee to England. He had no desire to be photographed beside Churchill.” On 14 May 1940, the first German troops appeared, and the Emperor welcomed them with open arms. Hermine wrote, “The first German soldier in front of the steps to the house was such an incredible relief that I cannot find words to describe it. I shall never forget the expression on the Kaiser’s face as he stood on the steps together with the commanding officer of a regiment – suddenly he was 30 years younger.”

On 4 June 1941, the Emperor died at House Doorn at the age of 82. He did not wish to be buried in Germany without the return of the monarchy, and so he was buried on the grounds of House Doorn. Adolf Hitler’s plans for a state funeral did not go ahead. Hermine wore a heavy black veil. After the funeral, Hermine decided to return to Silesia. Her last visit to Doorn would be in 1944. In 1945, she was ordered to evacuate, and she was tricked into going to Berlin. She was arrested and taken to Frankfurt an der Oder, where she would spend her last years under house arrest in the Russian zone.

On 5 August 1947, Hermine began to feel tired, and a doctor diagnosed purulent tonsillitis. By 7 August, Hermine’s neck was so swollen that she was no longer able to eat and drink. Breathing suddenly became very hard, and when the doctor finally arrived, there was very little he could do. She died later that same day of a heart attack. Hermine’s will was clear – she wanted her body to be returned to Doorn to be buried beside the Emperor. Unfortunately, this never happened and she was eventually interred in the Antique Temple in Potsdam, alongside the Emperor’s first wife, Auguste Viktoria.

The post Hermine Reuss of Greiz – An Empress in Exile (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 17, 2019

From Queen Victoria to the Crown Princess of Prussia – 18 December 1861

From Queen Victoria to the Crown Princess of Prussia – Windsor Castle, 18 December 1861

Queen Victoria’s husband had died on 14 December 1861

Bless you for your beautiful letter of Sunday received yesterday! Oh! My poor child indeed, ‘Why may the earth not swallow us up?’ Why not? How am I alive after witnessing what I have done? Oh! I who prayed daily that we might die together and I never survive him! I who felt, when in those blessed arms clasped and held tight in the sacred hours at night, when the world seemed only to be ourselves, but nothing could part us. I felt so very insecure. I always repeated: ‘And God will protect us!’ though trembling always for his safety when he was a moment out of my sight. I never dreamt of the physical possibility of such a calamity – such an awful catastrophe for me – for all. What is to become of us all? Of the unhappy country, of Europe, of all? For you all, the loss of such a father is totally irreparable! I will do all I can to follow out all his wishes – to live for you all and for my duties.

But how I, who leant on him for all and everything – without whom I did nothing, moved not a finger, arranged not a print or photograph, didn’t put on a gown or bonnet if he didn’t approve it shall be able to gon, to live, to move, to help myself in difficult moment? How I shall long to ask his advice! Oh! It is too, too weary! The day – the night (above all the night) is too sad and weary. The days never pass! I try to feel and think that I am living on with him, and that his pure and perfect spirit is guiding me and leading me and inspiring me! But my own dear child, so worthy of him, so like him in mind, my life as I considered it is gone, past, closed! Pleasure, joy – all is for ever gone. Think of Osborne, of the Highlands, of – oh! of Christmas – the 10th of February1 – all, all belong to a precious past which will for ever and ever be engraven on my dreary heart!

But you, his children, his flesh and blood can cheer your wretched mother’s crushed and bruised hart with your tender love and in trying to be like him! One alone (who does his best and feels his loss most deeply) is utterly unlike him and this is a cross.2 Alice3 has behaved and is behaving in a manner which commands the respect and admiration of all, while she is a real support to me. She is quite my right hand. All the others are most tender – Arthur4 (who is so like dearest Papa) touchingly so. Sweet little Beatrice5 comes to lie in my bed every morning which is a comfort. I long so to cling to and clasp a loving being. Oh! How I admired Papa! How in love I was with him! How everything about him was beautiful and precious in my eyes! Oh! How, how I miss all, all! Oh! Oh! The bitterness of this – of this woe!

I saw him twice on Sunday – beautiful as marble – and the features so perfect, though grown very thin. He was surrounded with flowers. I did not go again. I felt I would rather (as I know he wished) keep the impression given of life and health than have this one sad though lovely image imprinted too strongly in my mind! I do hope you will come in two or three weeks; it will be such a blessing then. I shall need your taste to help me in carrying out works to his memory which I shall want his aid to render at all worthy of him! You know his taste. You have inherited it. I chose this morning a spot in Frogmore Garden for a mausoleum for us.

Now God bless and protect you. Kindest remembrance and thanks to the King and Queen.6 How the Queen admired my own darling!7

The post From Queen Victoria to the Crown Princess of Prussia – 18 December 1861 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 16, 2019

From the Queen to the German Crown Princess – 17 December 1878

From the Queen to the German Crown Princess – Windsor Castle, 17 December 1878

I saw Sir William Jenner1 this morning. He saw her frequently the last day – and she seemed so pleased to see him, grasped his hand, and was delighted with the letter I sent through him. “Dear handwriting,” she said, “I am sorry for all the anxiety this causes dear Mama.”

She did not suffer much he thinks that day – and sank from exhaustion very, very much like beloved Papa – and the same day, how wonderful yet how touching – united in their end as in their lives. She had his unselfishness and courage and, I fear, his want of virality.

The feeling here is quite wonderful. It is as much as in ’61. From the highest to the lowest all feel not only for me – but deplore her untimely – and as they said in one of the papers “holy death” – for she gave her life for her children.

Oh! That it can be my own loved child – and that dread for infection which I think very shocking should deter Fritz2 and others from going there. I do think it very distressing. Poor Louis3 feels it awfully.4

The post From the Queen to the German Crown Princess – 17 December 1878 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Hermine Reuss of Greiz – An Empress in Exile (Part one)

My book about Hermine Reuss of Greiz “Hermine: An Empress in Exile” will be released in 2020. Click here to stay up to date on pre-orders and the definitive release date!

Hermine Reuss of Greiz was born on 17 December 1887 as the fifth child and fourth daughter of Heinrich XXII, Prince Reuss of Greiz, and Princess Ida Mathilde Adelheid of Schaumburg-Lippe. Her elder brother had been injured during a childhood surgery, leaving him mentally and physically disabled. Her parents had been praying for a boy, but they would not have another son. Her mother gave birth to a namesake daughter in 1891 and died shortly after of complications. Her heartbroken father never married again.

The death of her mother and the disability of her brother cast a long shadow over her childhood. Hermine was especially close to her elder sister Carolina, who would later briefly become Grand Duchess of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. The sisters were not close with their brother as his disability made it difficult to communicate with him. The family spent the winters at their father’s residence in Greiz and the summers in the hunting lodge near Greiz. Summer vacations were spent in Castle Burgk on the Saale and Hermine was especially fond of Burgk.

At the age of 14, Hermine lost her father as well. He had come back to Reuss in March against the advice of his doctors, who knew that it would be bad for his health. With his last bit of strength, he managed to visit the grave of Princess Ida, before dying on 19 April 1902. Although her brother officially became the reigning Prince Reuss of Greiz, Heinrich XIV, Prince Reuss Younger Line served as regent for him.

Hermine had a fascination for her future second husband, Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, from an early age. It was her aunt Princess Marie Reuss of Greiz, who had married Count Friedrich of Ysenburg and Büdingen in 1875, who often came to visit and brought her niece photos and postcards of the man she idolised. “Ever since I was a child, the Emperor inspired my imagination. My aunt, who knew of my enthusiasm, helped to make my heart beat faster.” She actually met him for the first time at the wedding of her sister Caroline to Wilhelm Ernst, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar on 30 April 1903 at Bückeburg Palace. Hermine was just 15 years old at the time and her sister only 19. “How could he have foreseen that this blushing little girl was his future wife? I stood there, frozen on the spot where the Emperor had received my greeting. The Emperor went on and chatted with my uncle.” Just two weeks later Hermine’s eldest sister Emma married Count Erich Kunigl von Ehrenburg.

Caroline’s marriage was destined to be unhappy and brief. Caroline was so miserable that she barely ate, choosing to nibble on chocolates, almonds and petit fours when she did. She had also taken up smoking. Caroline died on 17 January 1905, just 20 years old. The cause of death was influenza. Hermine later wrote, “In her heart of hearts, she did not wish to live.” In 1904, Emma married Freiherr Ferdinand von Gnagnoni, leaving just Hermine and Ida unmarried. She was taken under the wings of Louise of Prussia, the Grand Duchess of Baden and the aunt of the future Wilhelm II. On 11 December 1906, Hermine married Prince Johann Georg of Schönaich-Carolath, a lieutenant colonel in the Second Regiment of the Dragoons in Berlin. They would spend the winters in an apartment in Berlin, while they spent the summers in Silesia at Castle Saabor with her parents-in-law.

They would have five children together: Hans Georg (born 1907), Georg Wilhelm (born 1909), Hermine Caroline (born 1910), Ferdinand Johann (born 1913) and finally Henriette (born 1918). Johann Georg suffered from tuberculosis throughout much of their marriage. He served in the First World War until he was unable to carry on. The end of the First World saw not only Emperor Wilhelm II abdicate but also her brother’s regent. Prince Johann Georg died on 6 April 1920 in the Wölfelsgrund sanitorium. He had spent the last eight months of his life in a wheelchair. Hermine was determined never to marry again, writing, “I was strongly determined to never to marry again, never to surrender the precious right to be the master of my soul.”

All of that would change in 1922 when her young son Georg Wilhelm wrote to the Emperor in his exile in the Netherlands.

“To His Majesty the Emperor,

Dear Kaiser,

I am only a little boy, but I want to fight for you when I am a man. I am sorry because you are so terribly lonely. Easter is coming. Mama will give us cake and coloured eggs. But I would gladly give up the cakes and the eggs if only I could bring you back. There are many little boys like me who love you.

Georg Wilhelm, Prince of Schönaich-Carolath”

Soon Hermine found herself and her children invited to House Doorn in the Netherlands.

Part two coming soon.

The post Hermine Reuss of Greiz – An Empress in Exile (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 15, 2019

From the Queen to the German Crown Princess – 16 December 1878

From the Queen to the German Crown Princess – Windsor Castle, 16 December 1878

I could not write till this evening as I have been overwhelmed with the work of receiving and sending telegrams, settling things, writing and receiving letters. The grief is great – terrible! My precious child who stood by me and upheld me seventeen years ago on the same day taken, and by such a fearful, awful disease. I was greatly alarmed from the first for the fever was so high – no sleep – the membranes increasing – the knowledge of her great, great weakness! She had darling Papa’s nature, and much of his self-sacrificing character and fearless and entire devotion to duty!1

The post From the Queen to the German Crown Princess – 16 December 1878 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 14, 2019

Charlotte Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin – A banished Princess

Charlotte Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was born on 4 December 1784 at Ludwigslust as the daughter of Frederick Francis I, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and Princess Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. She was one of three surviving siblings, and her elder sister Louise Charlotte became the maternal grandmother of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort. She was known to have been intelligent, but her formal education was unfortunately neglected. She was later described as having had a temper, great imagination and being unreliable. She was also kind and generous.

In 1804, her first cousin, the future Christian VIII of Denmark, the son of her father’s sister Sophia Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, visited Germany to stay at his uncle’s court. He fell in love with the sensuous Charlotte Frederica at first sight. He told her, “You have an angel’s face, little Charlotte Frederica.” To which she responded, “Yes, and a scruffy body and a hellish temper!”1 They were married on 21 June 1806 at Ludwigslust. They took up residence at Amalienborg in Copenhagen. Their first son was stillborn the following year, but on 6 October 1808, she gave birth to a son who lived.

Charlotte Frederica did not fit into the stiff Danish royal court, and she liked spending money to such an extent that her husband was forced to apologise for her behaviour. In just three months, she had spent her entire allowance for the next three years. He also told her, “You buy all kinds of weird dresses and hats, and if you were beautifully dressed, I could understand. But you look like something from the lost goods office.”2 During one particularly dull evening, she asked the servants to bring in snow. The servant presented her with a pyramid of round snowballs on a fine silver tray. Proclaiming a snowball fight, Charlotte Frederica threw one at her sister-in-law Princess Juliane Sophie who screamed and jumped to shake off the remaining snow. Her husband was not amused and promptly dragged Charlotte Frederica home.

In 1809, Charlotte Frederica was accused of having a relationship with her singing teacher, the composer Edouard du Puy. They often practised operas, and sometimes they were found holding one another, which he often waved away by saying it was an act from an opera. A chambermaid later claimed to have seen a black-haired man in her bed. Her husband began divorce proceedings, which became final om 31 March 1810. She was initially banished to Horsens, and she was forbidden from seeing her son again. She was sent a new portrait of him every year. She continued to spend excessively and blamed her husband for her current situation. During her time at Horsens, she focussed on music and poetry, embroidery. She continued to proclaim her innocence and described herself as a victim of slander and intrigue. She also continued to correspond with her former husband. Du Puy was banished from Denmark.

Charlotte Frederica always hoped that she would be free once her son became King, saying, “When my son has become King and can decide for himself, he will get me out of my prison, and then I will not forget you (the people).”3 She lived in Horsens until 1829 and then moved to Rome, where she settled in the Palazzo Bernini under the name Mrs von Gothen, and she became a Catholic.

She died in Rome on 13 July 1840 at the age of 55, and she was buried in the Teutonic Cemetery in Vatican City, where her grave was recently opened and was strangely found empty in the search for a missing girl. Her son funded the monument on her grave.

The post Charlotte Frederica of Mecklenburg-Schwerin – A banished Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.