Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 201

November 12, 2019

Zizi Lambrino – “La misere noire” (Part one)

Zizi Lambrino was born on 3 October 1898 as the daughter of Constantin Lambrino and Euphrosine Alcaz. She was sent to a convent school in France where she lived until 1910 when she returned to Bucharest. There, she became part of the aristocratic society and learned English, playing the piano, painting and singing. Zizi moved with her mother to Jassy, where they had lived in a one-bedroom apartment. Zizi then captured the eye of Crown Prince Carol (later King Carol II of Romania).

Embed from Getty Images

Their relationship had begun earlier during the First World War, and Carol often picked her up from home for drives in his Rolls-Royce and games of bridge with his friends. Zizi later joined a group of women sewing and knitting for Carol’s mother, hoping to see more of him. She usually worked until 7 P.M. and then waited in the garden to meet with Carol. Zizi later wrote, “The loves of princes are like those of the most humble.”

Carol had been given the command of a mountain cavalry regiment in the Carpathian Mountains, but even that would not deter him from seeing Zizi. She simply moved in with friends to be near him. One day he simply abandoned his post, rented a car and took Zizi across the German lines to Odessa (under German occupation at the time) in Ukraine. Although they passed the Romanian side of the border without a problem, he was recognised at the other end and told to go only as far as Odessa. A German officer was sent along with them to keep him under surveillance. However, the Germans did not care about stopping any marriage – putting the Crown Prince of Romania in an awkward position would only be beneficial to them.

In Odessa, he found an Orthodox priest willing to perform a marriage, and they finally married on 14 September 1918. Zizi had fallen ill the night before with food poisoning, but the wedding went ahead, even though she had a fever. She wore a homemade gown of white crepe de chine, and she later wrote, “a poor honest dress of a marriage of love where it scarcely mattered that the man I married was called to rule.” The Romanian consul wired the news to Carol’s father Ferdinand I of Romania and his mother, Marie. Carol then informed his parents that he would renounce his right to the throne for Zizi. The Romanian constitution specially forbade the heir to the throne to marry anyone but a foreign-born Princess of equivalent rank. His parents were devastated by the news. Marie travelled to see her son, and he begged her for her sympathy. She asked him to give up Zizi temporarily, at least until the war was over. She promised him that he would be free to go with Zizi but “not at a moment when his flight was a desertion.” She wanted nothing more than to save him.

Carol was convicted for desertion by his own father and imprisoned in a monastery for two and a half months. Zizi was brought back to Jassy by one of Marie’s ladies-in-waiting where she searched the newspapers for any announcement of their marriage – but she found none. Marie visited her son several times during his imprisonment and wrote after one visit, “He simply howls for her.” Carol eventually agreed to a temporary annulment, and his mother wrote, “His heart is breaking over it, but he agrees to the inevitable, but I do not know how he will stand it.” Although she had won, it was “a cruel and sickening victory.”

In November 1918, Carol returned to Jassy to lead his regiment to victory, and he saw Zizi standing there with the police behind her. He had been ordered not to have any contact with her, and he had already appealed to Marie in frantic letters. He was finally only allowed to say goodbye to her after he signed the papers for a permanent annulment. He met her at the house of one his mother’s ladies-in-waiting. Reports back to his mother stated that the meeting was “long and painful” and “somewhat stormy” on Zizi’s side. The following day, Carol returned to his regiment.1

Part two coming soon.

The post Zizi Lambrino – “La misere noire” (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 11, 2019

Elizabeth of Pomerania – An Empress of legendary strength

Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia married four times. His fourth and last wife was Elizabeth of Pomerania. She was the wife who gave the emperor the most children – six. She was also the only wife to outlive him.

Granddaughter of the Polish King

Elizabeth of Pomerania was born around 1346 or 1347. She was the only surviving daughter of Bogislaw V, Duke of Pomerania, and his first wife, Elizabeth of Poland. Through her mother, she was a granddaughter of Casimir III, King of Poland, and his first wife, Aldona-Anna of Lithuania.

Elizabeth’s mother died in 1361. Soon afterwards, King Casimir took Elizabeth and her brother Casimir to live at his court. He treated Casimir of Pomerania as his possible successor and was probably hoping to arrange a prestigious marriage for Elizabeth. He did not have to wait long. In July 1362, the King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV, lost his third wife, Anna of Swidnica in childbirth. Even though he had surviving children, it would be best for him to stay married. Elizabeth, being Anna’s second cousin, and a granddaughter of a king seemed like a good match.

The Strong Empress

Charles and Elizabeth were married on 21 May 1363 in Krakow, Poland. Charles was forty-seven, and Elizabeth was about sixteen. This marriage broke a coalition against Charles led by his son-in-law, Duke Rudolf IV of Austria, and renewed his alliances with the Polish and Hungarian kings. About a month after the wedding, Charles crowned his two-year-old son, Wenceslaus, from his previous marriage, as King of Bohemia. Three days later, on 18 June 1363, Elizabeth was crowned as Queen of Bohemia in St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. The coronation of Wenceslaus was to show that he was Charles legitimate successor, and in the event of Elizabeth having sons, Wenceslaus would remain ahead of them in the succession.

The next year, a grand feast and congress of monarchs were held in Weirzynek, Poland. Elizabeth was present at the feast with her husband, grandfather, and the kings of Hungary and Cyprus. Elizabeth was described as a physically strong, lively and confident woman. Many tales are told about her legendary strength. According to these legends, she often entertained guests by bending horseshoes, breaking swords and tearing armour with her own bare hands! Some believe her strength was inherited from her Lithuanian grandmother, Aldona-Anna. Apparently, the Lithuanians were famous for their physical strength. Others suggest that it came from her father or her maternal grandfather, the Polish king.

In 1366, Elizabeth gave birth to her first child Anne, who would later marry Richard II of England. On 15 February 1368, she gave birth to her first son, Sigismund. Since he was the second surviving son, his birth was probably not greeted with the same rejoicing as that of his elder half-brother Wenceslaus, seven years earlier. That same year Elizabeth received an extraordinary honour, and she travelled with Charles to Rome. There on 1 November, she was crowned Holy Roman Empress by Pope Urban V.

Elizabeth would give Charles four more children. In 1370, a son – John, in 1372, a son – Charles, in 1373, a daughter – Margaret, and finally in 1377, a son – Henry. Charles and Henry only lived for a year, but John and Margaret would both reach adulthood. Wenceslaus, being the Emperor’s eldest son, was favoured by him over Elizabeth’s children. Elizabeth does not seem to have been happy by this and clearly preferred her own children. It seems that she would have preferred her eldest son, Sigismund, to be Charles’ heir over Wenceslaus. Apparently, relations between Wenceslaus and Sigismund were never good. Sigismund, however, would eventually be married to an heiress of Hungary, which seems to have pleased Elizabeth.

Despite Charles’ preference of his older son, relations between him and Elizabeth seem to have been harmonious. In 1371, Charles was seriously ill, and Elizabeth made a pilgrimage for his health. She walked from their main residence of Karlstejn to St. Vitus Cathedral, where she prayed and offered up gifts for his health. Eventually, Charles recovered, but he still did not have much time left. Charles died on 29 November 1378 in Prague. Wenceslaus became the new king of Bohemia and Germany. Due to Elizabeth’s strained relationship with Wenceslaus, she left court soon afterwards.

Life After Empress

In her widowhood, Elizabeth spent her time raising her four surviving children who were between five and twelve years of age at Charles’ death. Her eldest son, Sigismund, left for Hungary soon afterwards, due to his betrothal to the heiress of Hungary, Mary. In December 1381, her eldest daughter Anne, left for England to marry King Richard II. Around the same time, a less impressive marriage was arranged for her second daughter, Margaret. She was married to John III, Burgrave of Nuremberg, a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire. Her second son John received the Duchy of Gorlitz.

Elizabeth was not politically active, but she seems to have supported Sigismund’s claim to Hungary. When he was crowned King of Hungary in 1387, Elizabeth must have been proud. She was also known to have kept a correspondence with her daughter, Queen Anne. Elizabeth lived the rest of her life in seclusion at Hradec Kralove, the dower town for Bohemian queens. She seems to have stayed away from Prague because of her poor relationship with her stepson.

Elizabeth died in Hradec Kralove on 14 February 1393 and was buried beside Charles in St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Although she did not live to see it, her son Sigismund triumphed over his brother Wenceslaus in the end. In 1400, Wenceslaus was deposed as King of Germany. Sigismund was then elected as King of Germany in 1411. Wenceslaus died childless in 1419, and Sigismund succeeded him as King of Bohemia. And finally, in 1433, he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor.1

The post Elizabeth of Pomerania – An Empress of legendary strength appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 10, 2019

Elisabeth von Gutmann – The Jewish Princess

Elisabeth von Gutmann was born on 6 January 1875 as the daughter of Wilhelm Wolf Isaak Gutmann and his second wife, Ida Wodianer. She had two full brothers and two half-brothers and a half-sister, from her father’s first marriage. Her father received a hereditary knighthood from Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria in 1878. Not much is known about Elisabeth’s early life and upbringing. She was raised in the Jewish faith but was baptised in the Catholic faith with the name Elisabeth Sarolta in January 1899.

Just a few days after the baptism, on 1 February 1899, Elisabeth married Baron Géza Erős of Bethlenfalva. She was widowed at the age of 31, and they had not had any children. During her time as a widow, she lived in Vienna. Under what circumstances she would meet her second husband, remains unclear. They probably met in 1914 when she learned about a relief fund for soldiers founded by her future husband – the future Franz I, Prince of Liechtenstein.

Prince Franz (public domain)

Prince Franz (public domain)Franz was the younger brother of the reigning Johann II, Prince of Liechtenstein and he was against the match because of Elisabeth’s origins. Due to this, Franz and Elisabeth did not officially marry then but gave each other the promise of marriage – a so-called Notehe. They were finally free to marry when Franz’s brother died without leaving issue on 11 February 1929 and Franz succeeded him. They were married on 22 July 1929 in Lainz near Vienna and Elisabeth became the Princess consort of Liechtenstein. The Nazis immediately focussed their attentions on her due to her Jewish origins.

Elisabeth became the first Princess consort who regularly visited Liechtenstein. She and her husband visited schools and hospitals and supported charities in the principalities. They founded the “Franz and Elsa Foundation” with benefitted the youth of Liechtenstein. Elisabeth also enjoyed wearing the national costumes of Liechtenstein and was a great dog-lover. She was popular among the people of Liechtenstein and became a mother figure to them.

The annexation of Austria led to Franz making Prince Franz Joseph – his grandnephew and heir – the regent over the principality and Elisabeth and Franz moved to Prague. At that time, the Nazi movement was growing in Liechtenstein. Franz would die just three months later on 25 July 1938, and Elisabeth then moved to Switzerland where she lived by Lake Lucerne.

Elisabeth died in her home by Lake Lucerne on 28 September 1947 after a short illness. She was initially buried in Dux in Liechtenstein, but her remains were later moved to the Cathedral of Vaduz.1

The post Elisabeth von Gutmann – The Jewish Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 9, 2019

Who was Queen Himiko?

As Japan recently enthroned their new emperor, Naruhito, debates have surfaced on female ascension to the Japanese throne. Japan has had empresses regnant in the past, and before Japan was even a country, other women ruled like the legendary Queen Himiko of Yamatai-koku (a country in what is now Japan during the Yayoi period).

Queen Himiko, who some call Pimiko, was born c. 170 CE in Yamatai-koku as the daughter of Emperor Suinin, and she is mentioned in Chinese, Japanese and Korean sources. Oddly, two of the oldest Japanese written histories (c. 712 Kojiki and c. 720 Nihon Shoki) omit her with some arguing she was purposely left out. However, Chinese sources, considered more accurate than the Japanese sources, stressed her importance for 3rd century Japan.

According to Chinese sources “Book of Wei”, she came to the throne after 70 or 80 years of unrest following the death of a male ruler. She never married and was assisted in running the country by her brother. Rarely seen in public, she only had one male servant while the thousands of others were women. The man had a specific duty to serve as a communicator and serve her food and drink. Himiko, who practised magic, was protected at all times by armed guards in her palace.

“Records of Wei” claims that upon her death in 248, the people would not obey the new king installed with unrest again hitting the area with thousands of deaths. To restore order, Himiko’s 13-year-old niece, Queen Iyo, was named monarch.

It is also claimed that Queen Himiko is the originator of the most important Shintō sanctuary in Japan: Grand Shrine of Ise. A legend in Japan states that Himiko was given the sacred mirror that served as a symbol of the sun goddess, and in 5BC she enshrined said mirror in the Grand Shrine of Ise.

Queen Himiko reigned for 50 to 60 years and was known to dispatch diplomatic missions to China during her time on the throne, helping to explain the Chinese information on her. She was even given a special honour by the Chinese Wei Dynasty who gave her the title of “Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei.”

It was not until 2009 that Queen Himiko’s 280 metres long tomb, built in a traditional keyhole-shape design, was believed to have been discovered by researchers at the National Museum of Japanese History near Nara. They presented evidence at the 75th annual meeting of the Japanese Archaeological Association regarding the burial site; however, the Imperial Palace has banned further excavation of the site to positively confirm it is her resting place.

Professor Hideki Harunar led the excavation and said about the Queen, “She is a very important part of Japanese history as she was the first queen, ruled for many years – although we do not know exactly how long – and has gone down in history as a very popular ruler.”

The post Who was Queen Himiko? appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 8, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – King Edward VII

On 9 November 1841, a baby boy was born at Buckingham Palace. The child was the second child of Queen Victoria and and was named Albert Edward after his father and his grandfather the Duke of Kent, though he would always be known by his nickname Bertie. Victoria had not wished to have another baby so soon after having their daughter Vicky the year before and hated being pregnant.

It is clear now looking back that Victoria suffered from post-natal depression after having baby Albert Edward and the ‘shadow side’ of marriage, the stuff of pregnancy and birth often plunged her into a darkness which she found very difficult to come out of. Victoria called the baby frightful and backward and took a long time to bond with him; even then the bond was never the same as with some of his siblings. There would be nine in the brood in total, each a somewhat burdensome bi-product of the passionate love between Albert and Victoria.

At just a month old, the new prince was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester by his mother amongst many other titles and honours and was set up for a lifetime of royal duty. To prepare him for his future role as king, Bertie was educated to the highest standard and had to follow a rigorous programme. The child was not as naturally academic as his elder sister was, but the best tutors and resources were provided. From early on in life, the prince learned history, geography, reading, writing, languages, dancing and poetry, but he never reached the standard required of him by his tutors and governesses.

(public domain)

(public domain)At seven and a half, Bertie left the nursery, and his education was planned by his father from then on and was taught by a succession of tutors who struggled with the boy. Every hour of Bertie’s day was taken up by lessons, and he was quite isolated and withdrawn, which became worse when Albert began to whip his son to bring him into line, which never really worked. In his teens, Bertie completed secondary studies before moving on to study at both Oxford and Cambridge. It was during this time that when left to his own devices, Bertie began to enjoy studying, and his fun character started to shine through after the years of isolation.

When he was around the age of twenty, Bertie began taking royal tours abroad. His mother had banned him from active military service despite him wishing for a military career, so meeting and greeting people on behalf of the Royal family was one of the only roles he was permitted to carry out. The Prince visited Rome and North America in these early years and made a good impression, although he did start to gain a reputation as a playboy. In 1861, Bertie was sent to Germany supposedly to view some military manoeuvres, but really he was there to meet Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Queen Victoria had already met the Princess and wished for Bertie to marry her, luckily the pair hit it off, and plans were made for their nuptials.

(public domain)

(public domain)While the wedding plans were being drawn up, Bertie went on a trip to Ireland where he spent three romantic nights with an actress named Nellie Clifden. His father Albert was disgusted at this behaviour and visited the prince in Cambridge to make his feelings clear, just two weeks later Prince Albert passed away. Queen Victoria never recovered from her loss and wore mourning for the rest of her life; she also never forgave Bertie as she believed Prince Albert’s deterioration was due to his behaviour.

After the death of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria gave up on a lot of royal duties, which then fell to the Prince of Wales. A long Royal tour of Egypt delayed the wedding to Princess Alexandra which took place on 10 March 1863. Albert Edward and Alexandra established their home at Marlborough house where they were known to be popular socialites; they always entertained lavishly at their home which Victoria did not like.

Despite being happy with his wife, the Prince of Wales would not give up his mistresses of which there were many of throughout the years. These included Alice Keppel, Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick and actress Lillie Langtry amongst a reported fifty others! Bertie’s wife knew of his affairs and seemed to tolerate them, as extra-marital relations were common in their fashionable social set.

The Prince of Wales later began to carry out the type of modern public appearances we know the royals to carry out today; he would attend dinners, open buildings and so on. Other than this, Victoria kept him out of the running of the country, and he was not even allowed to view official documents, meaning he was ill-prepared for becoming king. It was not until 1898 that Victoria allowed her son any say in running the country. Over the years Bertie instead busied himself with travelling, socialising, spending time with his mistresses and also having his own children with Princess Alexandra. Together they had six children; including a son who died after just a day and their heir to the throne Albert Victor who sadly died aged 28. It was the couple’s second son who would later become King George V.

On 22 January 1901, Queen Victoria died after a reign of an incredible 63 years. For 59 of those years, Albert Edward had been Prince of Wales. After a delay because of illness, Bertie was crowned King Edward VII on 9 August 1902, he chose not to be called Albert as that was his father’s name. At the coronation, Bertie had a special pew put out to seat all of his lovers and mistresses which the shocked press called ‘the king’s loose box’. Bertie’s accession to the throne was welcomed by the English people. For the king himself, however, it was an honour which had come to him too late in life, and he said: “I would have liked it twenty years ago”.

King Edward set about making changes straight away with refurbishing the royal palaces, giving Osborne House to the state, introducing new honours and bringing back traditions such as the State Opening of Parliament. It seemed he had been sitting on such plans for some time.

King Edward was known as the uncle of Europe due to being related to many of the royal houses. He used this position to bolster Britain’s foreign affairs and made many overseas visits. In 1903, he visited French President Émile Loubet which laid the foundations for the future Entente Cordiale. Signed in 1904, the Entente ended centuries of rivalry with the French and brought Britain out of a period of isolation from European politics.

King Edward VII is also remembered for his military reforms, including the introduction of an army medical service and building Dreadnought ships, all of which were vital in the wars he would not live to see. These reforms and his involvement in politics show another side to the much-maligned man who was not taken seriously for much of his life, and if he had lived longer, we would have surely seen a lot more from him.

On 6 May 1910, after years of suffering from cancer and bronchitis, King Edward VII died just minutes after his son the soon-to-be King George V had told him that a horse had won in a race. Fittingly the fun-loving king’s last words were about the horse race “yes I’ve heard of it, I’m very glad”. He died with his wife by his side and was succeeded by his son King George V.1

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – King Edward VII appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 7, 2019

Marie of Hesse – The saintly Empress (Part two)

Read part one here.

On 2 March 1855, Marie’s husband became Emperor upon the death of his father. Both Marie and Alexander were by his side when he died. Their coronation took place on 17 August 1856, with Alexander placing a crown on Marie’s head as she knelt before him. When she arose, it clattered to the floor, but Alexander calmly placed it on her head again.

During the summer of 1864, as their eldest son courted Dagmar of Denmark, a swelling was discovered on his spine. He deteriorated slowly and in April 1865, he was diagnosed with cerebrospinal meningitis, and he suffered a stroke in France. Dagmar was informed with a telegram, “Nicholas has received the Last Rites. Pray for us and come if you can.”1 The family and Dagmar hurried to his side and were there when he died on 24 April 1865 at the age of 21.

Alexander had never been a stranger to mistresses and Marie turned a blind eye. She asked him,” I ask you to respect the woman in me, even if you won’t be able to respect the empress.”2 Despite the many mistresses, Alexander remained devoted to his family. In 1866, he became involved with Princess Ekaterina Dolgorukova and that same spring; he survived an attack. They would go on to have four children together, and they contracted a morganatic marriage after Marie’s death. As Alexander went through his mistresses, the Russian court considered Marie a saint for enduring it all.

In October 1866, Dagmar – once engaged to their son Nicholas – married the new heir Alexander, the future Alexander III. Marie could only feel for Dagmar and wrote, “It’s so sad to think what might have been, and one’s heart bleeds for poor Minny (Dagmar) who must feel it so, stepping over the threshold of a home she’d planned so delightfully with another.”3 A son was born to the couple on 18 May 1868 – the future Nicholas II. Marie was present during the birth, which bothered Dagmar “intensely!”4

In early 1880, it became clear that Marie was dying. Marie was in Cannes, and Alexander ordered her home. Marie wrote, “No one asked my opinion. This is a cruel decision. They’d treat a sick housemaid better.”5 Her ladies-in-waiting feared that she would die on her way to Russia, but she made it to the Winter Palace. Fears that Alexander would marry his mistress as soon as she was dead arose. Ladies-in-waiting prayed, “Lord protect our empress, because as soon as her eyes are closed, the tsar will marry the odalisque!”6 Marie was beginning to put her affairs in order and spent her days in bed. Alexander must have realised that Marie knew what would happen after her death, and he told his brother, “For God’s sake, don’t mention the empress to me, it hurts.”7 Marie wrote in her will that she wished to be buried in a simple white dress without a royal crown. She also requested that no autopsy be done. She began having hallucinations and started talking to them.

On the early morning of 3 June 1880, Marie was found dead at the Winter Palace, consumed by tuberculosis. Alexander wrote, “My God, welcome her soul and forgive me my sins. My double life ends today. I am sorry, but she (Ekaterina) doesn’t hide her joy. She talks immediately about legalising our situation; this mistrust kills me. I’ll do it all for her but not against the national interest.”8 A lady-in-waiting wrote, “It was during the night that the angel of death came for her very quietly, while the palace slept. A solitary death was the final chord in a life so far from vanity and earthly fame.”9

Marie was buried on 9 June, and Alexander married Ekaterina just 40 days after Marie’s death. Alexander was killed by a terrorist bomb the following year.

The post Marie of Hesse – The saintly Empress (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 6, 2019

Marie of Hesse – The saintly Empress (Part one)

Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine was born on 8 August 1824 as the daughter of Louis II, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine and Princess Wilhelmine of Baden. Her biological father could also be Baron August von Senarclens de Grancy, but she was recognised as his daughter by Louis. Marie spent most of her childhood at Heiligenberg with her mother and brother Alexander, but her mother would tragically die of tuberculosis when Marie was just 11 years old. Marie and Alexander moved back to Darmstadt where their father ruled as Grand Duke since 1830.

In 1839, Tsarevich Alexander Nikolaevich, the future Alexander II of Russia, visited Darmstadt and was instantly attracted to her. He wrote, “I liked her terribly at first sight. If you permit it, father, I will come back to Darmstadt after England.”1 Both he and his father had heard the rumours of her possible paternity but as long as Louis recognised her as his daughter, that was good enough for them. Alexander’s mother Alexandra Feodorovna (born Charlotte of Prussia) was not so happy with the rumours, but he wrote to her, “I love her, and I would rather give up the throne, than not marry her. I will marry only her, that’s my decision!”2 Alexander’s father forbade the court from discussing the rumours.

Alexander travelled on to England where he met the 20-year-old Queen Victoria who became quite smitten with him. She wrote, “I am quite in love with the Grand Duke, a dear delightful young man. The Grand Duke is so very strong, you are whisked around like in a waltz which is very pleasant… I never enjoyed myself more.”3 Alexander’s father reminded him that a marriage with Queen Victoria was really quite impossible, but he was certainly welcome to return to Darmstadt.

Alexander returned to Marie, where he sent his adjutant to ask Marie’s father for her hand in marriage. Alexander’s father was delighted and wrote, “Our joy, the joy of the whole family is indescribable, this sweet Marie is the fulfilment of our hopes. How I envy those, who met her before me.”4 However, upon Alexander’s return to Russia, he also promptly returned to the bed of his mother’s maids-of-honour. His father then threatened to disinherit him though that came to nothing. Marie was still only 14 years old at the time of the engagement, and so the actual wedding was postponed until she was 16 years old.

Meanwhile, Marie received instruction in the Russian Orthodox religion. Their engagement was officially announced in April 1840. In June 1840, her future mother-in-law met with her and gave her approval.

In August 1840, Marie set out for Russia with her brother Alexander. She arrived to continuous festivities, and she had a hard time adapting to her new surroundings – not surprising considering her age. On 17 December 1840, she was received into the Russian Orthodox Church and received the name Maria Alexandrovna. The following day, she and Alexander were officially betrothed. Her future sister-in-law would later write in her memoirs, “Marie won the hearts of all those Russians who could get to know her. Sasha (Alexander II) became more attached to her every day, feeling that his choice fell on God-given. Their mutual trust grew as they recognised each other. […] Dad joyfully watched the manifestation of the strength of this young character and admired Marie’s self-control. This, in his opinion, balanced the lack of energy in Sasha’s lack of energy fro which he constantly worried about.”

Marie herself later wrote that life in the Russian court demanded “daily heroism.” She “lived like a volunteer fireman, ready to jump up at the alarm. Of course, I wasn’t too sure about where to run or what to do.”5

Marie and Alexander were married on 28 April 1841 at the Winter Palace. She wore a white dress embroidered with silver and diamonds. She also wore a velvet robe with ermine and white satin and a diamond tiara, earrings, a necklace and bracelets. The Winter Palace would also become their first home, and they spent the summer at Tsarkoye Selo. Their first child – a daughter named Alexandra – was born on 30 August 1842. A son and heir named Nicholas was born on 20 September 1843, followed by Alexander on 10 March 1845, Vladimir on 22 April 1847, Alexei on 14 January 1850, Maria on 17 October 1853, Sergei on 11 May 1857 and Paul on 3 October 1860. Their eldest daughter Alexander would tragically die of infant meningitis on 10 July 1849. One day, Marie and Alexander even tried to contact her spirit with the help of a Scottish medium. The many pregnancies affected Marie’s health, and she began to visit spas to recover. She became very thin, and although Alexander continued to compliment her, she once replied, “The only thing I am wonderful for is the anatomical theatre – a teaching skeleton, covered with a thick layer of rouge and power.”6 She was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

Part two coming soon.

The post Marie of Hesse – The saintly Empress (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 5, 2019

Marie of Mecklenburg-Strelitz – The maligned Princess

Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Strelitz was born on 8 May 1878 as the daughter of Adolf Friedrich V, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Princess Elisabeth of Anhalt. She was their eldest daughter, and she had a younger sister named Jutta and two younger brothers named Adolphus Frederick (who would later succeed their father) and Karl Borwin. She and Jutta were raised by governesses, and she had little contact with her parents. They were very ignorant of how the world worked and when she was told of the birth of Prince of Edward of York (later King Edward VIII), she thought it very odd that Mary (his mother) should have a baby.

Probably because of her ignorance of the world, her youth became marked by a scandal. She became pregnant by a palace servant named Hecht, who was responsible for turning off the gas lights in her bedroom and those of her siblings. It was only brought to her mother’s attention when Marie was about to have the baby. The story quickly spread around the royal courts of Europe after Hecht consulted a lawyer because of his dismissal.

Marie’s parents refused to have anything to do with her and insisted on her being sent away. Even Queen Victoria had an opinion, “It is too awful & shameful & almost sinful to send the poor Baby away. I hear fm (sic) a reliable source that the family have forbidden that poor unhappy girl’s name ever being mentioned in the family… I think it is too wicked.” Marie’s grandmother Augusta (born Augusta of Cambridge – a granddaughter of King George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz) believed she had been terrorised by Hecht or even drugged or hypnotised. The Duchess of York, the future Queen Mary, who also happened to be Marie’s cousin, supported Marie by publicly appearing with her, driving around. Her husband, the future King George V, later wrote, “I certainly think the English relations have behaved better & are more sensible about it all. The parents are the worst and ought to be ashamed of themselves.”1

A daughter was born to Marie in 1898, and she was raised under the protection of her grandmother Augusta.

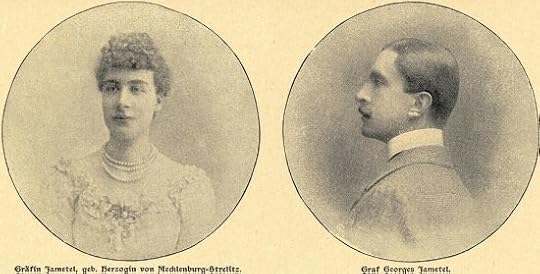

Marie and Count George Jametel (public domain)

Marie and Count George Jametel (public domain)On 22 June 1899, Marie married a Frenchman, Comte Jametel, but her parents refused to attend her wedding. Her father did settle $200,000 on her, and they lived off the interest in Paris. They went on to have two children George and Marie Auguste, but the marriage was unhappy. It soon became apparent that he had only married her for her money and went on to have a very public affair with Infanta Eulalia of Spain, a daughter of Isabella II of Spain.

Marie sought to divorce her husband in 1908 and paid for it with nearly her entire fortune. Her younger brother Karl Borwin challenged Comte Jametel to a duel in defence of her honour, and Karl Borwin was killed.

Embed from Getty Images

She remarried to Prince Julius Ernst of Lippe on 11 August 1914, and this marriage was much happier, and they too had two children together: Elisabeth and Ernst August. Julius Ernst was the uncle of Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands – the consort of Queen Juliana of the Netherlands and she and her husband were among the guests at their wedding.

Embed from Getty Images

She died on 14 October 1948 of pneumonia.

The post Marie of Mecklenburg-Strelitz – The maligned Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 4, 2019

Anastasia The Musical Review

Most will remember the 1997 film Anastasia in which Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia escapes from the clutches of an evil zombified Rasputin as the only one in her family. The story is based upon the legend that Anastasia somehow escaped the murder of her family (which we now know she didn’t) and the many people who tried to get to her grandmother Maria Feodorovna pretending to be her.

The Anastasia Musical premiered on Broadway in 2017 and has since been translated into Dutch to be performed in the Circustheater in Scheveningen. There are some differences with the film – including the fact that the zombified Rasputin has been replaced as the bad guy by a Bolshevik General called Gleb who is ordered to kill Anya (Anastasia) and several of the songs have been omitted and replaced with other songs.

The show was absolutely wonderful, filled with beautiful memories of the former glory of Imperial Russia and the story of a girl who slowly pieces together her own memory. The sets are great and innovative, allowing for quick changes between palaces, ballet, streets and even a railway track. The leading lady had a great voice and certainly wowed us all. If only Anastasia could have had a happy ending like this musical.

Anastasia The Musical premiered at the Circus Theatre in Scheveningen on 22 September 2019.

The post Anastasia The Musical Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 3, 2019

Feodora of Saxe-Meiningen – The unloved and misunderstood Princess

Princess Feodora of Saxe-Meiningen was born on 12 May 1879 as the daughter of Bernhard III, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen, and his wife, Princess Charlotte of Prussia. She was Queen Victoria’s first great-grandchild. She would turn out to be their only child – her mother simply declared she would have no more.

Feodora was close to her grandmother, Victoria, Princess Royal and later Empress Frederick. Even Queen Victoria found her daughter’s fussing over Feodora a bit much and wrote, “As regards the baby I think you are hardly a fair judge. Hardly anyone I know has such a culte for little babies as you have.”1 Nevertheless, after Queen Victoria met Feodora during her Golden Jubilee in 1887, she too became fond of her, calling her “sweet little Feo.”2

The relationship with her mother never quite materialised, and she often went to stay with her grandmother at Friedrichshof. As an only child, she probably had quite a lonely childhood. She didn’t even have her cousins as playmates as her mother did not get along with her brother Emperor Wilhelm II. By 1890, Feodora began to display some of the same health problems that plagued her mother. She was often violently ill, with diarrhoea, shivering, headaches and pain in her limbs. Her grandmother wrote, “I find dear little Feo hardly grown, she is very plain just now, especially in profile – a huge mouth & nose & chin – no cheeks, no colour – the body of a child of 5 and a head that might well belong to a grown-up person!”3 By 1893, she was still “the shortest child I ever saw.”4 However, she was “a good little child & far easier to manage than her Mama was & makes one far less anxious.”5 She had inherited her mother’s love of gossip though and her grandmother wrote, “I am afraid she will be her Mama all over again!”6

Charlotte was only too happy to let Feodora stay with her grandmother as it meant more freedom to travel. Feodora’s first offer of marriage came when she was 16 years old. The 52-year-old exiled Prince Peter Karageorgevich – later King of Serbia – asked for her hand in marriage. Her mother proudly declared, “for such a throne, she is far too good.” The large age gap was probably also considered. The next prospective bridegroom was Prince Alfred, Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the son of Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia but nothing came of it, and Alfred committed suicide in 1899. In October 1897, Feodora became engaged to Prince Henry XXX of Reuss, who was 15 years older than her. Her grandmother wrote, “It is of course not an advantageous marriage in terms of rank or position, but if Feo is happy, which she really seems to be, and the parents are satisfied, one ought to be glad. I am very glad he is older than she is, and if he is wise and steady and firm, he may do her a vast deal of good, and it may turn out very well, but she has had a strange example in her mother, and is a strange little creature.”7

Feodora and Henry (public domain)

Feodora and Henry (public domain)Their wedding was postponed after Henry’s father died early in 1898, but they eventually married on 24 September at the Lutheran Church at Breslau. Feodora wore a gown of white satin, trimmed with myrtle and orange blossom and lace. She also wore her mother’s wedding veil and diamonds pins that belonged to her grandmother. They left for their new home at Schloss Neuhoff later that afternoon. Henry soon returned to his duties with the army while Feodora joined a reading circle and regularly visited the opera and the theatre in Berlin. Feodora had wanted to have children of her own, but they would never have any. Feodora and Henry travelled to England in July 1900 where the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha wrote of her, “Feo and her uninteresting husband are here. She looks hideous, a dried-up little fashioned chip, with hair à la madone.”8

Around this time, Feodora also suffered a period of serious ill-health. She suffered severe pains, and her legs were partially paralysed. Feodora herself believed she suffered from a virulent form of malaria. Her mother, who suffered similar symptoms, was completely unsympathetic and would not hear of her daughter. Recent analysis suggests that both women were suffering from porphyria, a disease that was little understood at the time. In December 1900, Charlotte wrote Feodora was, “pale, thin, ugly, all freshness gone, funnily dressed, hair parted on the forehead (like a dairymaid), talking of dancing, acting, Lieutenants, not looking at anything, inquiring after nobody!! I could hardly believe this curious, loud personage had been my Child!! I cannot love her! & my heart seemed & felt a stone.”9 She went on a few months later, “How can a Child’s mind be so poisoned & totally changed in 2 years by such a stupid man?”10 A reconciliation seemed further away than ever. Charlotte even spread the rumour that Feodora was suffering from a venereal disease and took her refusal to be examined by a doctor as an admission of guilt.

In 1903, Henry was transferred to Flensburg, close to the Danish border. They moved into a small house there with a garden. They bought horses so they could go riding together and Feodora’s health vastly improved. Feodora continued to try and conceive, and she also spent four weeks at a sanatorium in Langenschwalbach. She also visited private clinics, and although the various treatments were painful, she wrote, “the more I suffered, the happier I was, as it was for Haz (her husband), for his future happiness, I should gladly have born more & the greater the pains, the surer I felt, that Döderlein (the doctor) was getting at the root of all evil & I nearer my prize.”

In February 1910, the doctor tried to inseminate her artificially, but a mistake made during the treatment nearly cost her her life. She forgave the doctor, writing, “a Professor is human & mistakes are human too.” A second operation the following year left her very weak, and she even begged her parents to come visit her. Charlotte hadn’t written to her daughter in nearly ten years and was bewildered by the dangerous treatments her daughter had undergone. Nevertheless, she did come to see Feodora.

In 1914, her parents finally succeeded as Duke and Duchess of Saxe-Meiningen. However, the First World War would leave her father as the last reigning Duke, and the monarchy was abolished in 1918. During the First World War, Henry served on the western front. Feodora was still often ill, and even her husband called her “operation mania.” She wanted to undergo another operation, but he refused to let her do it, until 1916, when she was suffering from vomiting and severe pains. He was clearly losing patience with her never-ending list of complaints. In October 1919, Feodora’s mother passed away after a heart attack.

After the First World War, Feodora and Henry paid occasional visits to England, but otherwise, the couple seemed to disappear from the world. Feodora became a long-time patient at the Buchwald-Hohenwiese sanatorium. Henry died on 22 March 1939, and now Feodora truly had nothing left to live for.

On 26 August 1945, Feodora made a suicide pact with a friend named Meta Schwenck and put her head in the gas oven. She was buried in the woods near the clinic, where her husband had also been buried. Her grave was subject to graverobbers, and several bones were missing when her grave was opened some 50 years after her death to investigate the possibility of her having had porphyria.

The post Feodora of Saxe-Meiningen – The unloved and misunderstood Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.