Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 203

October 23, 2019

Jane Seymour – The best-loved Queen

Jane Seymour was born on an unrecorded date, though it is likely to have been between October 1507 and October 1508. She was almost certainly born at Wolfhall to parents Sir John Seymour and Margery Wentworth. There is very little information available on Jane’s childhood, but she probably grew up at Wolfhall. There are also no records of any education she may have received. There is evidence that she was able to read and write, at least. In later life, she was known to be an expert needlewoman.

Her elder brother Edward was appointed to the household of King Henry VIII’s sister Mary, eventually leading to a career at court. Meanwhile, Jane stayed at home. Unusually, Jane’s younger sister Elizabeth married Sir Anthony Ughtred some time before 1530. There is evidence that Jane secured a place in the household of Catherine of Aragon though we don’t know exactly when she arrived at court. It is likely that this was just before King Henry VIII decided to divorce her around 1527. Jane stood on the sidelines as Catherine – whom she admired- was put aside for Anne Boleyn. Jane probably joined Catherine when she was exiled from court in 1531, and she was probably also present when Catherine was informed that Henry had married Anne. Catherine was also told that she should not be called Queen and that Henry would no longer provide for her expenses and the wages of her servants. In August 1533, the reorganisation took place with her allowance reduced to 12,000 crowns. Catherine was forced to move to a remote residence at Buckden and took only ten ladies with her. Jane was not amongst them.

Jane probably returned home around this time, and a marriage was finally suggested for her – the groom’s name was William Dormer. By then, she was around 25 years old, and the prospect must have excited her. However, the marriage never took place, and he instead married Mary Sidney in 1535. Then, at last, in 1535, Jane received a new court appointment. Jane was shy and did not stand out from Queen Anne’s ladies.

Nevertheless, Henry – who must have seen her during her time in Catherine’s household – finally really noticed her. On 4 September 1535, Henry arrived at Wolfhall during his autumn progress. Jane was almost certainly present, as was Anne Boleyn, and soon Jane was in Henry’s every thought. Henry gave Jane a miniature of his portrait, which she wore around her neck. Anne spotted the necklace and ripped it off, injuring her hand in the process.

However, at the time, Anne was pregnant, and no one envisioned Jane becoming anything more than Henry’s mistress. The death of Catherine of Aragon in January 1536 must have saddened Jane. On the day of Catherine’s funeral, Anne miscarried her pregnancy. Anne blamed it on Henry himself, who she had caught with Jane sitting on his knees. For Jane, this opened a whole new realm of possibilities. She probably received advice from her supporters on how to proceed but was not such a pawn as some might like to imagine. Jane set her sights on becoming the Queen of England.

At the end of April 1536, Jane and Henry had an understanding; now they just needed to be rid of Anne. Events were set in motion on 30 April when Mark Smeaton – a musician in Anne’s household – was arrested, and he had admitted to adultery the following morning. Then Anne herself was arrested, followed by her brother George and the courtiers Henry Norris, Francis Weston, William Brereton, Thomas Wyatt and Richard Page. They were all accused of being Anne’s lovers. On 15 May, Anne and her brother were found guilty. From the others, all except Page and Wyat were found guilty. On 17 May, the five men were beheaded on Tower Hill and on 19 May Anne was beheaded within the Tower walls. The official betrothal of Henry and Jane took place the following day.

Jane married Henry on 30 May 1536 in the Queen’s Closet at York Place although it was agreed to keep the wedding a secret for a few more days. However, rumours soon began to appear and Jane first publicly appeared as the new Queen of England on 2 June. She was formally proclaimed Queen two days later at Greenwich. On 6 June, her brother Edward was created Viscount Beauchamp. Jane was now suddenly the centre of attention, and she revelled in her time as Queen.

Jane had known her stepdaughter Mary from her time in Queen Catherine’s household, and she soon hoped that she could reconcile Mary and her father. She was less concerned about Elizabeth. However, Mary was expected to agree to the invalidity of her parents’ marriage, and this she would not agree to. The situation escalated to the point where the Imperial Ambassador wrote to Mary, begging her to submit for her life was in danger. Mary had no choice but to submit. Jane probably wrote to Mary and Mary certainly wrote back, addressing her letter to “the Queen’s grace my good mother.” In July, Jane and Henry set out to meet with Mary and the visit was a great success. Mary soon received her own household and was invited back to court. On Mary’s first visit back, Henry declared “some of you were desirous that I should put this jewel to death,” upon which Mary fainted.

The following autumn, Jane made her only political move when she fell to her knees in public in front of Henry and begged him to restore the abbeys during the Pilgrimage of Grace. He angrily told her to think about other matters and roaring that “he had often told her not to meddle with his affairs.” She was reminded of what had happened to her predecessor.

By the end of the year, there was still no sign of pregnancy, and Jane became worried. However, by late February or early March, she realised she was pregnant after nearly a year of marriage. On 27 May, she felt the child move for the first time. Henry was delighted and was ready to satisfy Jane’s every whim.

On 9 October, Jane went into labour at Hampton Court Palace, but it would be easy. She was still in labour two days later, and it wasn’t until 12 October that Jane was delivered of a son. Three days after the exhausting labour, she was wrapped in furs and carried to her son’s christening. However, she did not attend the christening but instead waited in an antechamber as her son was carried in a grand procession. After the procession, he was handed back to her for her to give him her blessing. Perhaps she had already begun to feel unwell during the festivities.

Jane quickly became delirious with a fever, and just two days after the christening, she received the last rites. She seemed to recover somewhat in the following days but on 24 October 1537, she passed away. There is no record that Henry was with her when she died, though he was at Hampton Court Palace and the news was brought to him immediately. Her stepdaughter Mary acted as chief mourner, and she made sure Jane was treated honourably. On 12 November, after laying in state in the chapel at Hampton Court, Jane was moved to St George’s Chapel at Windsor where she still rests – with Henry.1

The post Jane Seymour – The best-loved Queen appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 22, 2019

Ludovika of Bavaria – The unhappy Duchess (Part two)

By May 1834, Ludovika’s worried mother wrote to her daughter Amelie that Ludovika had become apathetic. One month earlier, she had given birth to her first daughter – named Helene. She had been one of a pair of twins, but Ludovika had miscarried the other twin earlier. Her husband had been busy building a palace in Munich – the Herzog Max Palais – and he also purchased Possenhofen Castle on Lake Starnberg. Ludovika fell in love with Possenhofen at first sight – it reminded her of her childhood home. However, their relationship began to deteriorate from that point. Maximilian began to have affairs and Ludovika’s sister Sophie reported to their mother that Maximilian had shown, “features of an incredible tyranny.”

Nevertheless, Ludovika continued to bear her husband children. On 24 December 1837, Ludovika gave birth to her second daughter – named Elisabeth but perhaps better known in history as Sisi. She was born with a tooth which was considered to be good luck. Her husband was deep in planning a trip to the middle east – a trip he would undertake without Ludovika. He came home just after their tenth wedding anniversary, and Ludovika soon found herself pregnant again. On 9 August 1839, Ludovika gave birth to a third – but second surviving – son at Possenhofen. He was named Karl Theodor. On 4 October 1841, she gave birth to another daughter – named Marie Sophie. Shortly after the birth, it became apparent that Ludovika’s mother Caroline was dying. Ludovika and her children travelled to Munich as soon as she was able and was so shocked by her mother’s appearance that she herself fell ill. On 13 November 1841, Caroline died surrounded by her family. Once again, Ludovika’s husband was nowhere to be found when she needed him.

In 1843, Ludovika found herself pregnant once more. On 30 September 1843, Ludovika gave birth to a daughter named Mathilde Ludovika. Ludovika’s eighth pregnancy ended in the stillbirth of a son on 8 December 1845. On 22 February 1847, she gave birth to her ninth child – a daughter named Sophie Charlotte. Her tenth and final pregnancy ended on 7 December 1849 with the birth of a healthy son named Maximilian Emanuel. Ludovika was now 41 years old, and she had spent the better part of her married life in continuous pregnancies. It was a miracle that she had survived.

Soon she was thinking about the marriage of her eldest daughter Helene, and she and her sister Sophie had the perfect candidate in mind, Sophie’s son Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. Franz Joseph had not seen his cousin since 1848 and Helene had, of course, grown up a lot. Her pious nature would fit in well with the Austrian court. However, his meeting with Ludovika, Helene en young Elisabeth led to him falling in love with Elisabeth instead of Helene. For Ludovika, seeing her daughter becoming Empress of Austria must have felt like a victory – even if it wasn’t the daughter that she had intended. On 24 April 1854, Elisabeth married Franz Joseph, and the family was catapulted to fame. Ludovika was at breakfast the morning after the wedding night and embraced her daughter. Elisabeth became pregnant quickly and her first child – a daughter named Sophie – was born on 5 March 1855. It was Ludovika’s first grandchild. A second grandchild – a daughter named Gisela – was born in 1856. Ludovika also acted as godmother for her second granddaughter. The relationship between Elisabeth and her mother-in-law Sophie was complicated, and Ludovika was often called in as a mediator. On 29 May 1857, Ludovika’s first granddaughter died in childhood, and Ludovika received the news via a telegram. Ludovika gathered up Helene, Marie Sophie and Mathilde Ludovika and travelled to Vienna to support Elisabeth during this difficult time.

Her other daughters were soon also getting married. Helene ended up marrying Maximilian Anton Lamoral, Hereditary Prince of Thurn and Taxis in 1858, Marie Sophie married King Francis II of the Two Sicilies in 1859, Mathilde Ludovika married King Francis’s younger half-brother Prince Louis, Count of Trani in 1861 and Sophie Charlotte – once engaged to the King of Bavaria – married Prince Ferdinand, Duke of Alençon in 1868. Her second son Karl Theodor married firstly Princess Sophie of Saxony in 1865 and secondly Infanta Maria Josepha of Portugal in 1874. Her third son Maximilian Emanuel married Princess Amalie of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha 1875. The marriage of her firstborn son Ludwig Wilhelm must have caused Ludovika some concerns. He had a child – named Marie – in 1858 with actress Henriette Mendel, and when she was pregnant again in 1859, he wanted to marry her. Ludovika had been aware of the child and had even acted as her godmother but him marrying a commoner was an entirely different story. And so, he gave up all his rights as the firstborn son in 1859. Henriette was raised to the nobility as Baroness von Wallersee, and they married at the end of May. Ludovika later wrote to her sister Marie that she wanted her son to be happy.

Her daughters’ marriages weren’t quite so happy. Two of her daughters ended up having extramarital children, and then there was, of course, the tragic tale of Elisabeth. Ludovika’s life would be interwoven with that of Elisabeth, and she was often stuck between her loyalty to her daughter and her loyalty to her sister. Possenhofen would become loved by her children and grandchildren and the coming of the railway considerably shortened the travel time to the idyllic castle. She often had a full house, especially after the death of Helene’s husband and the end of the monarchy in the Two Sicilies which affected Marie Sophie and Mathilde Ludovika. Although Ludovika herself did not face major illnesses, she did suffer from migraines and often relied on someone to read or write letters for her in her later years.

In September 1878, Ludovika and Maximilian celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary with a grand party at Schloss Tegernsee where they had been married. She later wrote that he had been “good to her” on their anniversary. Ten years, the family gathered again to celebrate Ludovika’s 80th birthday in style. By then, Ludovika had become quite lonely and melancholic. The death of Helene in 1890 hit her hard, as did her grandson Rudolf’s suicide 1889 and her husband’s death in 1888. Her own health started to deteriorate quickly, and Ludovika focussed on her one remaining wish – to find her granddaughter Amelie (the daughter of Karl-Theodor and Princess Sophie of Saxony) a good husband. She found him – Wilhelm, Duke of Urach – but she did not live long enough to see her get married. In January 1892, Ludovika began to suffer from flu-like symptoms. From the end of January, she unable to get out of bed. Soon, her family began to gather around her. Amelie was by her side and told her it was best to sleep – to which Ludovika groggily agreed.

In the early morning of 26 January 1892 – just before 4 A.M. – with only Sophie Charlotte and two doctors by her side, Ludovika passed away in her sleep. Luckily, she would not have the witness the fates that would befall Elisabeth and Sophie Charlotte.1

The post Ludovika of Bavaria – The unhappy Duchess (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 21, 2019

Ludovika of Bavaria – The unhappy Duchess (Part one)

Princess Ludovika of Bavaria was born on 30 August 1808 in the Munich Residenz as the daughter of King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria and his second wife, Caroline of Baden. She was the half-sister of King Ludwig I of Bavaria. Her birth was complicated, and it had already not been an easy pregnancy for Caroline. She had also been most troubled by the death of her sister Marie in childbirth just three months earlier.

Ludovika was baptised the following day with the names Ludovika Wilhelmine with her aunt Wilhelmine standing as godmother. Ludovika had five half-siblings (of which four survived to adulthood) from her father’s first marriage and seven siblings (of which four daughters and Ludovika herself survived to adulthood) from his marriage to her mother. The five daughters received lessons in literature, geography and history from Friedrich Thiersch. However, romantic tales from literature were strictly forbidden. All the Princesses were good students, and Thiersch was pleased with them. They were raised bilingual and spoke both German and French. Especially for Ludovika, her parents also hired a naturalist who taught her and her sisters all about botany. The central figure in the girls’ lives was Charlotte von Roggenbach – who was their governess. Schloss Nymphenburg and its idyllic park were the perfect places to grow up, and Ludovika was known to have been especially fond of the park.

Her happy childhood came to an abrupt end in 1821 with the death of her 10-year-old sister Maximiliane, nicknamed Ni in the family. She returned home from the theatre in the dead of winter and caught a cold that quickly became worse. Her mother devoted all her time to nursing her sick daughter. On 4 February 1821, Maximiliane died in her mother’s arms. She had always been her mother’s favourite, and Caroline was devastated.

The first of Ludovika’s (full) sisters to marry was Amalie. On 21 November 1822, Amalie married the future King John of Saxony. For Ludovika it was the second painful goodbye in short period of time. One year later, Amalie’s twin sister Elisabeth married the future Frederick William IV of Prussia. Yet another year later, Ludovika’s sister Sophie married Archduke Franz Karl of Austria. Now only Maria Anna and Ludovika remained unmarried. Ludovika had attended Sophie’s wedding in the Augustine Church in Vienna, and she had fallen in love with the future King Miguel I of Portugal, who was not even in town for the wedding but was actually in exile. Ludovika was by then 16 years old, and Miguel was 22. Miguel too was charmed by Ludovika, and he even asked her father for her hand in marriage. However, he was refused – not in the least because of the reason for his exile, the rebellion against his father. Her father probably also already had another match in mind – Duke Maximilian Joseph in Bavaria, his grandnephew who had previously been promised to Maximiliane. For Ludovika – who would see her three elder sisters become Queen – it was not a particularly good match.

On 13 October 1825, Ludovika’s father died quite suddenly in his sleep at the age of 69. His successor was Ludovika’s elder half-brother who now became King Ludwig I. The shock of his sudden death left Ludovika reeling and also delayed her marriage. Ludwig promptly had his stepmother and unmarried half-sisters moved to Würzburg. Caroline was devastated when he also tried to remove court preacher Schmidt from her service and angrily wrote to him, “Schmidt is mine, and he will remain mine.” The breach in the family bond was never healed.

Caroline took her two unmarried daughters with her to Vienna, where they stayed for several months. Miguel was also still there, and he and Ludovika often met each other. However, they were forced to say goodbye when Caroline decided to go back to Munich and to renovate Schloss Biederstein, which had been left to her. They were not there for long when Ludovika’s aunt Frederica, the exiled Queen of Sweden, in Karlsruhe became ill. It soon became apparent that Frederica was not going to recover. She wanted to go to the Côte d’Azur and travelled there via Switzerland to consult with doctors. Caroline and her two daughters followed. She never made it to the Côte d’Azur and died in Lausanne on 25 September 1826. Frederica’s two daughters Amalia and Cecilie – who also happened to be friends with Ludovika – were devastated and Caroline quickly took her two nieces under her wing. At the end of the year, Caroline and her two daughters were back in Würzburg, and Ludovika found the time to write to Duke Maximilian how incredibly cold it was there.

In February 1828, marriage negotiations were finally concluded, and Ludovika’s wedding was set for 9 September 1828. Ludovika would later say, “Neither of us wanted to get married.” Yet, they did and keeping Ludovika close by was a comfort for Caroline. The wedding took place in the St Quirinus Church on the bank of the Tegernsee. Just a few days after the wedding, a letter arrived from the newly proclaimed King Miguel of Portugal, asking for Ludovika’s hand in marriage. Caroline was forced to tell him her daughter was already married, but she did not inform her daughter of the letter. She could have been a Queen like her sisters.

Her new husband Maximilian was often away, and Ludovika wrote in her diary that she spent her first wedding anniversary alone and in tears “from the morning until the evening.” It wasn’t until the end of 1830 that Ludovika found herself pregnant for the first time. In the Cotta Palace in Munich, Ludovika gave birth to her first child on 21 June 1831 – her son was named Ludwig Wilhelm. Her labour lasted over ten hours. A cholera outbreak would force the family south to Italy, taking their newborn son with them. Ludovika loved Rome and spent a lot of time visiting the sights of the city. Their time in Italy would bring the couple closer together. By the time they returned north, Ludovika was pregnant again. On 24 December 1832, Ludovika gave birth to a second son – named Wilhelm Karl. Tragically, he would die just weeks later on 13 February 1833 of whooping cough. Following the death of her son, Ludovika often had periods of depression and melancholy.1

Part two coming soon.

The post Ludovika of Bavaria – The unhappy Duchess (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

“Sisi” novels to be adapted to TV-series

Allison Pataki’s “Sisi” novels, based on the life of Empress Elisabeth of Austria, are set to be adapted into a TV-series by Amy Jenkins, who is also a writer for Netflix’s The Crown.

Allison Pataki has written two novels called “The Accidental Empress” (which I reviewed in 2015) and “Sisi: Empress on Her Own.” The series is set to span from 1853 until the start of World War One (which surprised me since Sisi will have been dead for 16 years by then!)

“Sisi was an extraordinary young empress,” Jenkins told Variety. “Charismatic and free-thinking, she was a royal rebel who set the Hapsburg court on fire in a surprisingly modern way.” Jenkins added that she was “looking forward to bringing a very feminine perspective to her fascinating struggle for self-determination.”

It will be the first English language TV series about Sisi, though most will know the legendary German language Sisi movies featuring Romy Schneider.

More info to come.

The post “Sisi” novels to be adapted to TV-series appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Netflix releases trailer for season 3 of The Crown

The post Netflix releases trailer for season 3 of The Crown appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 20, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – Sir John Conroy

John Conroy was born on 21 October 1786 as the son of John Ponsonby Conroy, Esq., and Margaret Wilson in Wales. Both his parents were Irish, and he was one of six siblings.

He entered the army at the age of 17, but he was not quite as successful as he might have hoped. His only success was marrying the daughter of his general. He married Elizabeth Fisher on 26 December 1808 in Dublin and was promoted to Second Captain on 13 March 1811 and appointed adjutant in the Corps of Artillery Drivers on 11 March 1817. He and Elizabeth went on to have six children together, and one child would die in childhood.

With the end of the Napoleonic Wars in sight, John was desperate for work. He was introduced to Prince Edward, Duke of Kent through his wife’s uncle Dr John Fisher, who was not only the Bishop of Salisbury but he had also served as a tutor for Prince Edward. He was taken into Prince Edward’s household. Upon the death of Prince Edward, John told everyone who was willing to listen that the Duke had entrusted the Duchess of Kent and the newborn Princess Victoria to his care. He held his position in the army until 1822 when he began to devote himself entirely to the Duchess of Kent. He began to take care of her issues, all while moaning about his own sacrifices. He made The Duchess of Kent feel like “an old stupid goose” and began to take advantage of her and was soon appointed comptroller of her household.

He also befriended the ageing Princess Sophia, who with her declining mind also quickly fell under John’s spell, and he treated her like a cash-cow. She bought him a house for his family, a country home in Reading and an estate in Wales. In 1823, his accounts contained just £100, but by 1825 they contained £22,000.

Soon, he and The Duchess of Kent were on a similar mission – becoming Regent for Victoria.

In 1827, John complained that the princess should not be surrounded by commoners, leading King George IV to appoint Conroy a Knight Commander of the Hanoverian Order and a Knight Bachelor and Victoria’s governess was made a Baroness.

The Duchess of Kent and John Conroy began their attempt to bend Victoria to their will, in a plan called “The Kensington System.” They believed that Victoria would most luckily succeed before her 18th birthday and would require a regent, such as her mother. The whole system was “to ensure that the Duchess had such influence over her daughter that the nation should have to assign her the regency.” Victoria’s education was to be kept in the Duchess’s hands so that “nothing and no one should be able to tear the daughter away from her.” Secondly, it was to “give the Princess Victoria an upbringing which would enable her in the future to be equal of her high position” and to “win her so high a place in the hearts of her future subjects, even before her accession, that she would assume the sceptre with a popularity never yet attained and rule with commensurate power.”

Victoria was intended to become detached from her uncles King George IV and his successor King William IV but also King Leopold of Belgium, who also had his eyes on the regency. The public would need to believe that Victoria and her mother were inseparable. In practice, this meant that Victoria was under constant surveillance, and everything was reported to John Conroy. She never saw anyone without a third person present and was never allowed to be alone. She slept in her mother’s bedchamber and her governess Lehzen sat with her until the Duchess came to bed. Victoria was constantly surrounded by John Conroy, but also his children. Victoria became quite resentful at being obliged to spent time with Victoire Conroy, whom she considered to be her social inferior. Victoria also resented her playmate’s father and her mother’s fascination with him. Victoria’s refusal to appoint John as her advisor angered him.

When Victoria became seriously ill in 1835, John did not believe her and thought it to be one of her whims. A few days later, Victoria became delirious, and even John now realised the seriousness. However, he seized the opportunity to have her confirm him as his private secretary. When Victoria refused, her mother came to John’s aide, but even she could not convince her daughter – sick as she was. He also pushed a pen into her hand, and she still refused to sign. She survived, but her recovery was quite slow. Throughout her ordeal, her only support had been Lehzen, her governess. Victoria later wrote, “at the risk of her health if not her life preserved the Queen from this horrible man.”

Victoria ascended the throne upon the death of her uncle King William IV just shortly after her 18th birthday – she had averted a regency. John and the Duchess of Kent spent the entire day trying to get close to the new Queen, but she refused to see them. John told Baron Stockmar, “I am completely beaten.” To salvage what he could, John began to demand a peerage and £3,000 a year. Queen Victoria agreed to the money – if only to be rid of him. However, a peerage would have allowed him to attend court and Victoria did not want that.

John eventually left to go abroad, realising that he would not be admitted to court and not wanting to remain in the Duchess of Kent’s household as she was also out of her daughter’s favour. He took whatever money he had left, and he eventually settled in his country home in Reading. He died there on 2 March 1854. The Duchess of Kent – by now back in favour – wrote to her daughter, “He has been of great use to me, but unfortunately has also done great harm.”1

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – Sir John Conroy appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 19, 2019

Lost Kingdoms: Kingdom of Holland

The Kingdom of Holland was set up by Napoleon Bonaparte for his brother Louis Bonaparte, who became the first King of Holland in 1806. Louis was – unhappily – married to Napoleon’s stepdaughter Hortense, who was thus the first – and as it would turn out the last – Queen of the Kingdom of Holland.

Queen Hortense (public domain)

Queen Hortense (public domain)The new King and Queen received a surprisingly warm welcome in their new Kingdom. However, Hortense was deeply unhappy in Holland, and the couple lived in different wings of the Royal Palace of Amsterdam. Hortense only lived briefly in her new Kingdom and returned to France after the death of their elder son.

Louis was a better King than Napoleon had expected and wanted him to be. Louis was determined to learn the language and even adopted the Dutch spelling of his name. Napoleon forced Louis to abdicate in 1810 and his eldest surviving son, the six-year-old Louis, became King Louis II of Holland for one week when the Kingdom was annexed into the French Empire. Hortense acted as regent for him.

And so after just four years, the Kingdom of Holland came to an end. After the fall of Napoleon, the House of Orange returned to power, eventually becoming Kings of the Netherlands in 1815.

The post Lost Kingdoms: Kingdom of Holland appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 18, 2019

Book News November 2019

The Prince & I: My Life with Prince Bira of Siam

Paperback – 12 November 2019 (US) & 7 October 2019 (UK)

The Prince & I is the story of the passionate love of Bira, Prince of Siam, grandson of King Mongkut of The King & I fame, and the young Englishwoman who would become his wife, Princess Ceril Birabongse. The fascinating autobiography charts the life of Prince and Princess Birabongse, a life that was constantly filled with excitement and fascinating people, including Noel Coward, Princess Marina, The Duchess of Kent, and even Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess. Illustrating her narrative with a selection of private photographs, extending from her childhood years to her elegant retirement on Lake Garda, the author paints a rich picture of life during the golden days of the 1930s, and of a man who was not only a Prince, but a sculptor, Olympic sailor, and racing driver – the only Southeast Asian Formula One driver of the 20th Century.

A Royal Christmas

Hardcover – 8 November 2019 (UK) & 15 November 2018 (US)

A Royal Christmas is the first official publication to explore the fascinating Christmas traditions of royalty past and present. Drawing on many previously unpublished objects and images from the Collection, this highly visual book offers insight into the influence and charm of royal festivities.

The book details the history of the royal broadcast, which is a cornerstone of Christmas for many people. It also discusses the introduction of Christmas trees to Britain by Queen Charlotte and how this custom was later popularised by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

The Wicked Wit of the Royal Family

Hardcover – 7 November 2019 (UK & US)

There is no doubt that the British royal family is THE most famous family in the world. Watched and picked over in the media for everything from fashion choices to baby bumps, sporting achievements to nightclub preferences, there doesn’t seem to be a moment when they can escape public scrutiny. But, somehow, they still manage to maintain a sense of humour – and it’s those flashes of fun and brilliance that this book celebrates.

From Prince Philip’s gaffe-prone remarks (most of which appear ON camera rather than off) to the ‘in’ jokes shared by the knowing smiles of the younger royals and the Queen’s wickedly dry and often bitingly funny remarks; from Prince Charles’s asides to the Duchess of Cornwall to the self-deprecating smile of the Duchess of Cambridge and the belly laughs that appeal to Prince Harry. This book presents the other side of royal protocol and perhaps gives a glimpse of the real lives of this much-loved clan.

The King’s Pearl: Henry VIII and His Daughter Mary

Paperback – 15 June 2019 (UK) & 1 November 2019 (US)

Mary Tudor has always been known as ‘Bloody Mary’, the name given to her by later Protestant chroniclers who vilified her for attempting to re-impose Roman Catholicism in England. Although a more nuanced picture of the first queen regnant has since emerged, she is still stereotyped, depicted as a tragic and lonely figure, personally and politically isolated after the annulment of her parents’ marriage and rescued from obscurity only through the good offices of Katherine Parr.

Although Henry doted on Mary as a child and called her his ‘pearl of the world’, her determination to side with her mother over the annulment both hurt him as a father and damaged perceptions of him as a monarch commanding unhesitating obedience. However, once Mary had finally been pressured into compliance, Henry reverted to being a loving father and Mary played an important role in court life.

As Melita Thomas points out, Mary was a gambler – and not just with cards. Later, she would risk all, including her life, to gain the throne. As a young girl of just seventeen she made the first throw of the dice, defiantly maintaining her claim to be Henry’s legitimate daughter against the determined attempts of Anne Boleyn and the king to break her spirit.

Lust, Lies and Monarchy: The Secrets Behind Britain’s Royal Portraits

Paperback – 1 November 2019 (US) & Unknown (UK)

People have long been fascinated by the stories behind royal portraits. This volume takes readers inside royal families by way of great paintings, like Holbein’s Henry VIII, van Dyck’s Charles I, Millais’ The Princes in the Tower, Freud’s Elizabeth II, and more. Featuring incredible, little known stories of the royals and illustrates, this beautiful collection is illustrated with color paintings, photos, family trees and Royal London walking tours with maps.

Elizabeth Widville, Lady Grey: Edward IV’s Chief Mistress and the ‘Pink Queen’

Hardcover – 31 July 2019 (UK) & 2 November 2019 (US)

Wife to Edward IV and mother to the Princes in the Tower and later Queen Elizabeth of York, Elizabeth Widville was a central figure during the War of the Roses. Much of her life is shrouded in speculation and myth even her name, commonly spelled as Woodville , is a hotly contested issue. Born in the turbulent fifteenth century, she was famed for her beauty and controversial second marriage to Edward IV, who she married just three years after he had displaced the Lancastrian Henry VI and claimed the English throne. As Queen Consort, Elizabeth s rise from commoner to royalty continues to capture modern imagination. Undoubtedly, it enriched the position of her family. Her elevated position and influence invoked hostility from Richard Neville, the Kingmaker , which later led to open discord and rebellion. Throughout her life and even after the death of her husband, Elizabeth remained politically influential: briefly proclaiming her son King Edward V of England before he was diposed by her brother-in-law, the infamous Richard III, she would later play an important role in securing the succession of Henry Tudor in 1485 and his marriage to her daughter Elizabeth of York, thus and ending the War of the Roses. Elizabeth Widville was an endlessly enigmatic historical figure, who has been obscured by dramatizations and misconceptions. In this fascinating and insightful biography, Dr John Ashdown-Hill brings shines a light on the truth of her life.

Elizabeth I (The English Monarchs Series)

Reprint Edition – 26 November 2019 (US & UK)

No one thought that Elizabeth would live to become Queen of England. Her father, Henry VIII, beheaded her mother, Anne Bolyn, for treason in 1536. He then disowned his daughter, declaring her illegitimate. But in 1544, Parliament reestablished the young princess in the line of succession after her half brother and her half sister. Endowed with immense personal courage and a keen awareness of her responsibility as a ruler, Elizabeth commanded throughout her reign the unwavering respect and allegiance of her subjects.

The Crown: The Official Companion, Volume 2

Hardcover – 19 November 2019 (US & UK)

The official companion to the second and third seasons of the Emmy-winning Netflix drama about the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, featuring additional historical background, expert commentary, and beautifully reproduced images

Uncrowned Queen: The Treacherous Life of Margaret Beaufort, Tudor Rebel

Hardcover – 7 November 2019 (US & UK)

During the bloody and uncertain days of the Wars of the Roses, Margaret Beaufort was married to the half brother of the Lancastrian king Henry VI. A year later she endured a traumatic birth that brought her and her son close to death. She was just thirteen years old.

As the battle for royal supremacy raged between the houses of Lancaster and York, Margaret, who was descended from Edward III and thus a critical threat, was forced to give up her son – she would be separated from him for fourteen years. But few could match Margaret for her boundless determination and steely courage. Surrounded by enemies and conspiracies in the enemy Yorkist court, Margaret remained steadfast, only just escaping the headman’s axes as she plotted to overthrow Richard III in her efforts to secure her son the throne.

Against all odds, in 1485 Henry Tudor was victorious on the battlefield at Bosworth. Through Margaret’s royal blood Henry was crowned Henry VII, King of England, and Margaret became the most powerful woman in England – Queen in all but name.

Nicola Tallis’s gripping account of Margaret’s life, one that saw the final passing of the Middle Ages, is a true thriller, revealing the life of an extraordinarily ambitious and devoted woman who risked everything to ultimately found the Tudor dynasty.

The Love Affairs of Mary Queen of Scots: A Political History

Hardcover – 5 November 2019 (US & UK)

Mary, Queen of Scots, also known as Mary Stuart, was one of the most well-known and controversial monarchs of the sixteenth century. She ascended to the throne of Scotland at only six days old and would eventually become ruler of four countries at once—Scotland, England, Ireland, and France. She was known for being intelligent, compassionate, and tolerant, despite the popularity of that time for religious persecution. Despite being well-liked, Mary’s reign was a tumultuous one: she was married three times, was forced to abdicate her throne, and was eventually imprisoned and beheaded by her cousin, Elizabeth I of England.

What caused Mary’s rapid descent from royalty? In this brand-new edition of the historical biography, Major Martin Hume analyzes Mary Queen of Scots’s fall from power based on her love affairs. Though many previous historians had assumed that her downfall was based on her virtue or vice, Hume claims in his history that Mary’s ruin was not based on her “goodness or badness as a woman, but from a certain weakness of character.”

Discover the ups and downs of Mary Stuart’s life and reign as queen in The Love Affairs of Mary Queen of Scots.

Anna of Denmark and Henrietta Maria: Virgins, Witches, and Catholic Queens (Queenship and Power)

Paperback – 4 December 2019 (US) & 6 November 2019 (UK)

This book examines how early Stuart queens navigated their roles as political players and artistic patrons in a culture deeply conflicted about the legitimacy of female authority. Anna of Denmark and Henrietta Maria both employed powerful female archetypes such as Amazons and the Virgin Mary in court performances. Susan Dunn-Hensley analyzes how darker images of usurping, contaminating women, epitomized by the witch, often merged with these celebratory depictions. By tracing these competing representations through the Jacobean and Caroline periods, Dunn-Hensley peels back layers of misogyny from historical scholarship and points to rich new lines of inquiry. Few have written about Anna’s religious beliefs, and comparing her Catholicism with Henrietta Maria’s illuminates the ways in which both women were politically subversive. This book offers an important corrective to centuries of negative representation, and contributes to a fuller understanding of the role of queenship in the English Civil War and the fall of the Stuart monarchy.

The Other Windsor Girl: A Novel of Princess Margaret, Royal Rebel

Paperback – 5 November 2019 (US) & 23 January 2020 (UK)

Diana, Catherine, Meghan…glamorous Princess Margaret outdid them all. Springing into post-World War II society, and quite naughty and haughty, she lived in a whirlwind of fame and notoriety. Georgie Blalock captures the fascinating, fast-living princess and her “set” as seen through the eyes of one of her ladies-in-waiting.

In dreary, post-war Britain, Princess Margaret captivates everyone with her cutting edge fashion sense and biting quips. The royal socialite, cigarette holder in one hand, cocktail in the other, sparkles in the company of her glittering entourage of wealthy young aristocrats known as the Margaret Set, but her outrageous lifestyle conflicts with her place as Queen Elizabeth’s younger sister. Can she be a dutiful princess while still dazzling the world on her own terms?

Post-war Britain isn’t glamorous for The Honorable Vera Strathmore. While writing scandalous novels, she dreams of living and working in New York, and regaining the happiness she enjoyed before her fiancé was killed in the war. A chance meeting with the Princess changes her life forever. Vera amuses the princess, and what—or who—Margaret wants, Margaret gets. Soon, Vera gains Margaret’s confidence and the privileged position of second lady-in-waiting to the Princess. Thrust into the center of Margaret’s social and royal life, Vera watches the princess’s love affair with dashing Captain Peter Townsend unfurl.

But while Margaret, as a member of the Royal Family, is not free to act on her desires, Vera soon wants the freedom to pursue her own dreams. As time and Princess Margaret’s scandalous behavior progress, both women will be forced to choose between status, duty, and love…

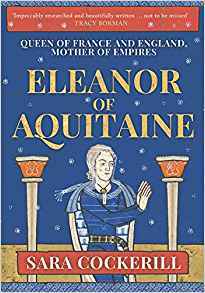

Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France and England, Mother of Empires

Hardcover – 15 November 2019 (UK) & 1 June 2020 (US)

In the competition for remarkable queens, Eleanor of Aquitaine tends to win. In fact, her story sometimes seems so extreme it ought to be made up.

The headlines: orphaned as a child, duchess in her own right, Queen of France crusader, survivor of a terrible battle, kidnapped by her own husband, captured by pirates, divorced for barrenness, Countess of Anjou, Queen of England, mother of at least five sons and three daughters, supporter of her sons’ rebellion against her own husband, his prisoner for fifteen years, ruler of England in her own right, traveller across the Pyrenees and Alps in winter in her late sixties and seventies, and mentor to the most remarkable queen medieval France was to know (her own granddaughter, obviously).

It might be thought that this material would need no embroidery. But the reality is that Eleanor of Aquitaine s life has been subjected to successive reinventions over the years, with the facts usually losing the battle with speculation and wishful thinking.

In this biography, Sara Cockerill has gone back to the primary sources and the wealth of recent first-rate scholarship, and assessed which of the claims about Eleanor can be sustained on the evidence. The result is a complete re-evaluation of this remarkable woman s even more remarkable life. A number of oft-repeated myths are debunked and a fresh vision of Eleanor emerges. In addition, the book includes the fruits of her own research, breaking new ground on Eleanor s relationship with the Church, her artistic patronage and her relationships with all of her children, including her family by her first marriage.

The post Book News November 2019 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 17, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – Maria Alexandrovna of Russia (Part two)

Maria quickly fell pregnant and gave birth to her first child – a son named Alfred – in October 1874. On 27 October, Queen Victoria wrote to her eldest daughter, “She has not had any drawback – and is as well and strong as possible and shows a very healthy constitution which is a great thing, is it not? She nurses the child – which will enchant you. As long as she remains at home – and does not publish the fact to the world – by taking the baby everywhere and can do it well – which they say she does now – I have nothing to say (beyond my unfortunately – from my very earliest childhood – totally insurmountable disgust for the process).” Maria breastfed her son, and when she did so during his christening, he threw up over her dress. The Princess of Wales (Alexandra of Denmark) reported that she handed over her son to her mother and “ran about with her big breast hanging down in front of everyone and wiped the dress clean!!!”1 Four daughters followed: Marie (born 1875), Victoria Melita (born 1876), Alexandra (born 1878) and Beatrice (born 1884). She also had a stillborn child in October 1879.

Alfred and Maria moved into Clarence House, where an Orthodox Chapel was installed for her. They also lived in Malta, where Alfred was stationed. After 1878, they also spent time in Coburg as it was expected that her husband would eventually succeed his uncle as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. In 1880, Maria lost her mother and the following year, her father was killed by a terrorist bomb. She and her husband hurried to St Petersburg for the funeral. Her elder brother had now become Alexander III of Russia.

In Coburg, Maria held court in the Palais Edinburg. She enjoyed her freedom there and was not under the watchful eye of her mother-in-law Queen Victoria. Her daughter Marie later said, “She was her own mistress; it was a small Kingdom perhaps, but her will was undiscussed, she took her orders from no one, and could live as she wished.”2

The first of her children to marry was Marie, who married Crown Prince Ferdinand of Romania on 10 January 1893. Alfred was devastated at his daughter’s marriage to a man whose country was by no means stable. Her first grandchild was born the following October; the future King Carol II of Romania. Maria was with her daughter until November. After Maria left, her daughter wrote to her, “Today you arrive in Coburg, how I wish I was with you. I feel it so terribly that you are gone, and when our little boy is particularly sweet, I always feel so sorry you are no more there to enjoy him.”3 That August, she and Alfred had also become Duke and Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha upon the death of Ernest II. Maria’s sister-in-law, the Empress Frederick, wrote to her daughter Sophie, “He will do it all so well, and Aunt Marie will love being No. 1, and reigning Duchess, I am sure.”4 Maria indeed savoured the moment of becoming Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

On 19 April 1894, Victoria Melita married Ernst Ludwig, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine and their daughter Elisabeth was born on 11 March 1895. It was an unhappy marriage that ended in divorce in 1901. The unexpected death of her brother Alexander III on 1 November 1894 stunned Maria, and she and Alfred arrived only just in time to say goodbye. On 20 April 1896, Maria’s third daughter Alexandra married the future Ernst II, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg (a grandson of Queen Victoria’s half-sister Feodora). Meanwhile, her only son, the young Alfred, worried her with his drinking and his health was suffering because of it. By early 1899, he was emaciated and almost unable to walk. He died on 6 February 1899 – still only 24 years old. A few months later Maria wrote to her eldest daughter, “Our poor, poor Alfred! He gave us only pain and trouble and yet one was always hoping for a better future, one was working for him and had an object in life. And now it all seems too dismal, too empty for words! In what hand will this dear home of ours get later on?”5 The succession to the Duchy now fell to the Duke of Connaught and his son, but he decided to renounce the succession and so it fell to the Duke of Albany, the posthumous of Prince Leopold.

Alfred, too, was devastated by his only son’s death, and he was “in a dreadful state.” He underwent several cures in Egypt and Hungary, but his health continued to decline. In May 1900, he went to take the waters at Herculesbad, but soon after his arrival, he began to have throat problems. Soon, he was unable to swallow, and he had to be fed by tube. At the end of June, a cancerous growth was discovered at the root of his tongue. He returned to Coburg, where doctors prepared to do a tracheotomy – to help him breathe. It would be too late, and he died on 30 July 1900 with Maria and three of their daughters by his side. Maria was now a widow at the age of 46.

Just a short while later, Maria was at Osborne when her mother-in-law Queen Victoria passed away. Although she kept several residences, her favourite one was her villa in Tegernsee in Bavaria. After Victoria Melita’s divorce, she returned to live with her mother for some time. She remarried to Cyril Vladimirovich, Grand Duke of Russia on 8 October 1905. On 15 July 1909, her youngest daughter Beatrice married Infante Alfonso of Spain, 3rd Duke of Galliera. Maria made frequent trips to Russia to stay with Victoria Melita, and she gained three more grandchildren from her daughter’s second marriage.

The outbreak of the First World War made things difficult for Maria, and after being attacked by an angry mob, Maria moved to Switzerland. She lost many family members during the Russian Revolution, including her nephew Nicholas II and his family. It also left in reduced circumstances, and much of her fortune had been held in trust in Russia. Her death came quite sudden on 25 October 1920, and she suffered a heart attack in her sleep. She was buried in Coburg beside her husband and son.

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – Maria Alexandrovna of Russia (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Program of the reburial of Queen Mother Helen of Romania

A full program of the coming reburial of Queen Mother Helen of Romania has been released. Queen Mother Helen, born Princess Helen of Greece and Denmark, died in exile in Switzerland in 1982 and was buried in the Bois-de-Vaux Cemetery there. In 2018, it was announced that her remains and those of her former husband King Carol II of Romania would be moved to the New Episcopal and Royal Cathedral.

Tomorrow – 18 October 2019 – Queen Mother Helen’s coffin will arrive at Otopeni Airport around noon. A military and religious ceremony will be performed in the presence of the former Royal family. Around 12.45 P.M. the funeral cortege will travel from Otopeni Airport to Curtea de Arges. The cortege will not make any stops but will slow down when passing through towns. At Curtea de Arges, the coffin will be placed in the old cathedral where the family will have a private moment of prayer. After this, the public is invited to pay their respects. Those wishing to bring flowers are asked to bring white ones and to lay them in front of the cathedral.

The following day – 19 October 2019 – the public can pay their respects until around 10 A.M. From noon to 12.40 P.M. the funeral service will take place in the old cathedral. The coffin will be carried in a military and religious procession to the New Episcopal and Royal Cathedral, where the reburial will take place from 1 P.M.

The post Program of the reburial of Queen Mother Helen of Romania appeared first on History of Royal Women.