Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 202

November 1, 2019

The Year of Queen Victoria – Queen Victoria’s father

As the fourth son and fifth child of King George III, Prince Edward had no idea that his only child would one day be the longest-reigning (until Queen Elizabeth II that is!) and most popular British monarchs in history.

He was born on 2 November 1767 to King George III and Queen Charlotte in Buckingham House in London. Edward was christened on 30 November 1767 with Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Duke Charles of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Hereditary Princess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, and Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel serving as godparents.

As was usual for princes, Edward served in the British military in the army and underwent training in Germany. He would be appointed brevet colonel in the British Army on 30 May 1786, and three years later, the Prince was appointed colonel of the 7th Regiment of Foot. His time in the military was not perfect, as he would return to England without leave, and as a result, was shipped to Gibraltar as an ordinary officer. He could not stand the heat in the country, so he requested to be transferred to Canada, which was granted.

Prince Edward was the first member of the British Royal Family to tour Upper Canada and would later be promoted to major-general in October 1793. During his time in Canada, he was given the title of Duke of Kent and Strathearn on 24 April 1799. He spent time in both Quebec and Nova Scotia before returning to Gibraltar in 1802.

When Prince Edward’s niece, Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales, died in 1817, the succession to the throne was in danger. Edward and two of his brothers (the Duke of Clarence – later King William IV – and the Duke of Cambridge) rushed into marriage contracts in bids to secure the throne. Their two other brothers, the Prince Regent and the Duke of York were estranged from their wives with no surviving legitimate children, and Edward’s sisters were childless and past childbearing age.

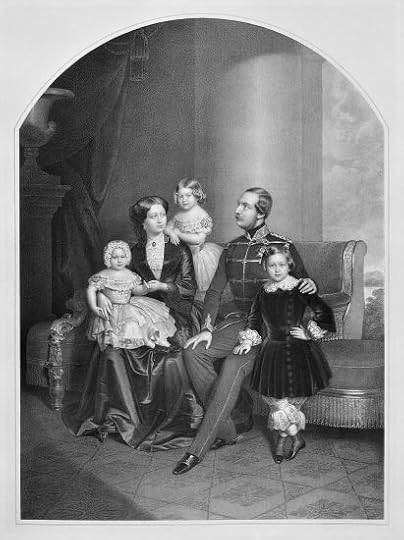

Thus, Prince Edward wed Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld on 29 May 1818 in Coburg in a Lutheran service and again on 11 July 1818 in Surrey. Slightly less than a year after their wedding, their only child, Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent, was born on 24 May 1819.

The Duke and Duchess of Kent’s new baby daughter was christened in Kensington Palace’s Cupola Room on 24 June 1819 in a private ceremony by the Archbishop of Canterbury. It was then that her Christian name of Alexandrina was given with her second name as Victoria. Her first name was in honour of her godfather, Emperor Alexander I of Russia while her second name honoured her mother.

It was said Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn was extremely proud of his baby daughter but would not get to see her grow up and become monarch. He died before she was a year old on 23 January 1820 at the age of 52 from pneumonia in Woolbrook Cottage. Six days later, his father, King George III, would die at the age of 81.

The Prince was buried in St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle on 12 February.

The post The Year of Queen Victoria – Queen Victoria’s father appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 31, 2019

Frederica of Hanover – The princess who followed her heart

Princess Frederica of Hanover was born in 1848. Her father was George, Crown Prince of Hanover and her mother was Princess Marie of Saxe-Altenberg. The Princess was given the title of Her Royal Highness when in Hanover but she was also addressed as Her Highness when in the United Kingdom as she was a great-granddaughter of King George III.

Frederica’s father succeeded to the throne of Hanover as King George V of Hanover in 1851. Little is known of Frederica and her siblings Marie and Ernest’s childhoods in Hanover but their father’s position made Frederica an attractive future bride.

(public domain)

(public domain)Otto von Bismark, the Prussian Prime Minister, contacted Hanover in 1866 about a possible match for the Princess and Prince Albrecht of Prussia was suggested as a potential groom for Frederica. However, it was not long before the Austro-Prussian war broke out and this plan was no longer feasible. King George V chose to side with the Austrians which led to the Prussian annexation of Hanover. Shockingly after this King George was overthrown, and despite his pleas to King William I of Prussia, who was also his cousin, he never returned to reign and his life was lived out in exile.

Princess Frederica had to leave Hanover and headed into exile with the rest of the family after her father was deposed. After moving around, her family settled in Austria at the Schloss Cumberland and her father became an honorary general in the British army before he passed away in 1878. During her time in exile, Frederica visited England a number of times to stay with family and she was popular in high society.

As time went on Frederica had two more suggestions for her hand in marriage; Alexander, the Prince of Orange, and Prince Leopold, her second cousin, the youngest son of Queen Victoria. In a surprising move, Frederica instead went with her heart and married for love, in a way the loss of her father’s title meant that she was free to marry who she wanted. The lucky man was Baron Alfons von Pawel-Rammingen who was classed as a commoner. Frederica knew Alfons from his role as her father’s equerry, though he was also a government official.

Frederica in her wedding dress (public domain via Royal Collection Trust)

Frederica in her wedding dress (public domain via Royal Collection Trust)Alfons was made a British citizen and the couple married in 1880 at Windsor Castle. A verse was read at the wedding which was written by the poet Tennyson. The heartfelt poem mentioned Frederica’s bond with her late father who was blind. Tennyson wrote ‘the blind king sees you today’ alluding to the late King of Hanover watching on from heaven.

The newlyweds moved into rooms in Hampton Court Palace, where they had one child, a daughter named Victoria. Sadly she passed away after only a few weeks of life and the couple had no more children. The pair threw themselves into London society and visited Osborne House regularly after this.

Frederica is well remembered for her devotion to charitable causes and public events. She was the patron of the Princess Frederica School which she opened in 1889. Frederica also opened a convalescent home for women in poverty who had given birth for after they were discharged from maternity homes. On top of this, she gave money to charities for the blind and deaf and was involved with the RSPCA.

Frederica and Alfons left Hampton Court in 1898 and then moved to Biarritz in France for most of the year, with visits to England. The couple lived a quiet life in later years and it was in France that Frederica passed away in 1926. The Princess’ body was returned to England for interment in St George’s Chapel, Windsor where she had been married forty years earlier. Alfons lived until 1932.

The post Frederica of Hanover – The princess who followed her heart appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 30, 2019

Downton Abbey Review – A royal visit

My personal love for Downton Abbey had died a quiet death alongside Matthew Crawley after season 3’s Christmas Special. I finished the series, of course, but it was never quite the same without him. I had to see the movie, especially after the trailer showed the plot was based around a royal visit by King George V and Queen Mary.

The movie picks up in 1927 – about a year and a half after the end of the series. Lady Mary, who was pregnant at the end of the series, has given birth to a daughter named Caroline. There is much excitement both upstairs and downstairs when a letter comes from Buckingham Palace, informing them that the King and Queen are coming to stay. Naturally, the servants rebel against being replaced by the royal servants who arrive well in advance. It’s an amusing storyline which cumulates in Mr Molesley making a fool of himself when he accidentally addresses the King. The better storyline is, of course, that of the King and Queen’s daughter Princess Mary who is having marital trouble. Though there may be some truth in the storyline (after all, doesn’t every marriage have trouble at some point?), Mary’s marriage was considered to be a love match. I especially liked the actress (Kate Phillips) who portrayed Mary.

Though the movie has quite a few storylines (Queen Mary’s servant is a kleptomaniac, Barrow arrested in a gar bar etc.), all seemed to be solved rather quickly, and it felt a little weak. Nevertheless, I enjoyed the trip back into time, and it was lovely seeing all my favourite characters again.

The post Downton Abbey Review – A royal visit appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 29, 2019

The Rain Queens of Balobedu

The Rain Queen – or Modjadji – is the hereditary Queen of Balobedu. The Balobedu people live in the Limpopo province in South Africa. Unlike many other monarchies, the succession is matrilineal. This means that the eldest daughter is the heir and men are completely banned from inheriting the throne.

The history of the Rain Queens is based on several stories, one of which states that a 16th-century chief was told that by impregnating his daughter, she would gain rain-making skills. The Rain Queen is hardly seen by her people, and she communicates through male councillors. When a Rain Queen dies, her body is rubbed in a way that skin comes off. This skin is kept and used to make rain pots. She is not supposed to marry but will have children by her relatives. Traditionally, if she is close to death, she ingests poison and appoints her eldest daughter as her successor. The Rain Queen is cared for by women called her “wives.”

In any case, the first Rain Queen was Maselekwane Modjadji I who reigned from 1800 until 1854. She lived in complete seclusion and committed ritual suicide in 1854. She was succeeded by her eldest daughter Masalanabo Modjadji II. She reigned until 1894 when she too committed ritual suicide. She reportedly had children, but it appears that she did not have daughters or her daughters predeceased her as she named the daughter of her sister as her heir. Khesetoane Modjadji III reigned from 1895 to 1959. Her daughter was Makoma Modjadji IV who broke with tradition and married Andreas Maake. She reigned from 1959 until 1980 and was succeeded by her daughter Mokope Modjadji V. She had three children, including an heir Princess Makheala but tragically, she died two days before her mother in 2001.

Princess Makheala’s daughter became the next Rain Queen as Makobo Modjadji VI at the age of 25. She was crowned in 2003, but some considered her too modern to become a Rain Queen. Tragically, the young Rain Queen died just two years later, officially of chronic meningitis, but there were a lot of rumours surrounding her death. Hospital staff said that she was suffering from AIDS.1 She left a son, Prince Lekukena (born 1998) and a daughter, Princess Masalanabo (born 2005). The father of her children later said, “She told me I was the man she had dreamt of meeting. We would have married and settled into a happy family life, but she was forbidden by ancient custom to take a husband.”

Developments in 2016 recognised the 11-year-old Princess Masalanabo as the new Rain Queen, and she is expected to be crowned as soon she turns 18.2

The post The Rain Queens of Balobedu appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 28, 2019

Anna of Swidnica – A beloved Empress

After the death of his second wife Charles of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia wanted to marry again in order to have a surviving son. He quickly decided that he would marry Anna of Swidnica, who was previously betrothed to his deceased son, Wenceslaus. Anna was the daughter of a second son of a prince of a small Polish territory. What made her such a desirable bride for the Emperor-in-waiting?

Anna, relative of the Kings of Poland and Hungary

Anna of Swidnica was born around 1339, as the only child of Henry II, joint-Duke of Swidnica (known as Schweidnitz in German), and his wife, Catherine. Anna’s father was the second son of Bernard, Duke of Swidnica and Kunigunde of Poland, who was in turn the daughter of Wladyslaw I, King of Poland and Hedwig of Kalisz. Her paternal grandfather was from the Silesian branch of Poland’s royal Piast dynasty. Through her paternal grandmother, she was a grand-niece of Casimir III, King of Poland, and first cousin-once-removed of King Louis I of Hungary, who both ruled during her lifetime.

Despite Anna’s illustrious connections on her father’s side, her mother’s origin is uncertain. Catherine was previously thought to be a daughter of Charles I, King of Hungary, either illegitimate or by one of his wives. The only two wives of his who could possibly be Catherine’s mother were his first/second wife, Maria of Bytom, or his third/fourth and last wife Elizabeth of Poland. However, it’s unlikely that Maria or Elizabeth could have been Catherine’s mother. The oldest sources on Maria state that she had no children. Elizabeth is described as having five sons, but there is no mention of any daughters. Also, if Elizabeth were Catherine’s mother, she and Henry would have been first cousins, since Elizabeth and Kunigunde were sisters. A special dispensation would be required, and there is no record of one for this marriage. One possibility is that Catherine was a Hungarian noblewoman instead of a princess. Since Henry was a low-ranking prince and nothing is said about his wife’s birth family, she probably did not have royal connections.

Anna’s father died between 1343 and 1345. Sometime after his death, Anna was sent to the Hungarian court for education. She was brought up by her great-aunt, the before-mentioned Elizabeth of Poland, Queen of Hungary.

Preparing for a Bright Future

The Hungarian court was one of the most splendid and powerful royal courts in Europe at the time. There, many girls of noble birth were prepared for a bright future. Anna was one of them. At the Hungarian court, Anna would have been educated in the usual subjects noble girls were taught. This included social conduct, religion, foreign languages, horse riding, music and dancing, household management, and how to be the ideal wife. But the Hungarian court offered an even more impressive education for the girls under its care – Anna was taught how to read and write, which was rare, even for the high-born in that day.

In January 1350, a son named Wenceslaus was born to Charles, King of Bohemia and Germany. Immediately after the birth, Charles made marriage plans for him. Swidnica may have been a small duchy, but it was strategically important to Bohemia. Swidnica was a division of the Duchy of Silesia, which was disputed continuously between the rulers of Poland and Bohemia. The dukes of Silesia came from a branch of Poland’s royal Piast dynasty. Anna’s uncle, Bolko II of Swidnica, was the most powerful of the Silesian princes. He was also the last independent of the Silesian dukes. Besides Swidnica, he also gained the Silesian duchies of Jower and Lwowek on the death of his uncle in 1346. Bolko married the Habsburg princess Agnes in 1338 in a move against Bohemia. However, in 1350, this marriage was still childless, so Anna was Bolko’s only heir. Charles betrothed his newborn son to eleven-year-old Anna, with the plan that this marriage would bring Bolko’s territories under Bohemian rule on the event of his death without children. Unfortunately, Wenceslaus died in December 1351. His mother, Anne of Bavaria, died a year later, so Charles decided to marry Anna himself.

The marriage plans for Anna were made immediately after the death of Charles’ second wife. On 27 May 1353, just three months after the death of Anne of Bavaria, Charles and Anna were married in Buda. Charles was 37, and Anna was 14. The wedding was attended by many illustrious guests, such as King Louis of Hungary, his mother, Elizabeth of Poland, Duke Albert II of Austria, Margrave Louis II of Brandenburg, and Duke Bolko II of Swidnica. Soon after the wedding, the new couple left for Anna’s homeland of Swidnica. There, Bolko issued a document confirming the succession of Anna and her children if he were to die with no sons.

On 28 July 1353, Anna was crowned as Queen of Bohemia in St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. On 9 February 1354, Anna was crowned as Queen of the Romans in Aachen Cathedral, Germany. Unlike Charles’ first two wives, Anna lived to see her husband be officially recognised as Holy Roman Emperor. Therefore, she was the first of his wives to be Holy Roman Empress.

Holy Roman Empress

(public domain)

(public domain)By 1355, Charles was finally recognised as Holy Roman Emperor. Now he just needed to be crowned. Anna followed him on his way to the imperial coronation. In January 1355, Anna reached northern Italy. She then went to Pisa, where she met up with Charles on 8 February. On 22 March, with a large retinue, they then set off for Rome. Among those accompanying them was an army to keep them safe during the long journey, German princes, and Anna’s relatives, the Silesian princes. They reached Rome on 2 April.

On Easter Sunday, 5 April 1355, Charles and Anna were crowned as Holy Roman Emperor and Empress in Rome. After the coronation, they rode on white horses to a grand feast. The new imperial couple seemed to be in no hurry to get back to Prague. Their journey back was quite eventful. On 6 May, they arrived back in Pisa, where they would spend the next few weeks. On the night of 19/20 May riots broke out in Pisa. The palace that Charles and Anna were staying in was set on fire. They escaped the building at the last minute, dressed only in their nightgowns. Charles put Anna on her horse and ordered her to flee the city to safety. After the riots were suppressed, Anna returned to Pisa. They left the city on 24 May but made many stops along the way. They finally returned to Prague on 15 September, after travelling through Germany. During this journey, Anna was accompanied by the poet and scholar Francesco Petrarch. He was one of the fathers of the Italian Renaissance. Anna and Petrarch seemed to grow close during the long journey, and she later corresponded with him.

Anna often accompanied Charles on his many travels. Hungary and Germany were two of the places they would often visit. In May 1357, Anna and Charles travelled with Elizabeth of Poland on a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Elizabeth of Hungary in Marburg. This pilgrimage was probably made in the hope of Anna having a child. In the spring of 1358, Anna gave birth to her first child, a daughter named Elizabeth. Hoping for a son, she expressed her disappointment in a letter to Petrarch.

Anna did not have to wait long for a son. On 26 February 1361, she gave birth to a son named Wenceslaus in Nuremberg. His birth was met with great rejoicing. Anna herself even informed the Pope about his birth. The birth of a son had increased Anna’s position. From then on, Charles would refer to her as his “beloved wife”. Anna was also said to be the most beautiful woman of her day. She was also known to be very intelligent.

Thanks to her literacy, Anna was known to have had a lively correspondence with some of the most influential people of her era, including Petrarch and Pope Innocent VI. She was clearly on her way to becoming a great Empress. Unfortunately, her promising life and career were cut short. On 11 July 1362, Anna gave birth to a third child, a son, who was stillborn. Anna died later that the same day at the age of 23. She was buried at St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague.

Anna of Swidnica is yet another queen whose promising life was cut short by childbirth. Given her talents, if she lived longer, she could have accomplished a lot more, and be better remembered today. Charles seemed to have mourned her death, unlike the death of his second wife. This time it would be another ten months before he remarried. His third wife was Anna’s second cousin, Elizabeth of Pomerania. Anna’s son would grow up to be Charles’s successor, King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia. He was also King of Germany, but he would never become Holy Roman Emperor. He inherited Anna’s lands in Swidnica after the death of her uncle in 1368.1

The post Anna of Swidnica – A beloved Empress appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 27, 2019

Ana de Mendoza, Princess of Eboli – The one-eyed beauty

Ana de Mendoza de la Cerda y de Silva Cifuentes was born on 29 June 1540 as the daughter of Diego Hurtado de Mendoza y de la Cerda and Catalina de Silva Cifuentes. As her father’s only child, she would become 2nd Princess of Mélito, 2nd Duchess of Francavilla and 3rd Countess of Aliano in her own right.

At the age of 13, Ana was married to Rui Gomes da Silva, 1st Prince of Éboli – who was a favourite of the future King Philip II of Spain. Their marriage was not consummated until 1557 due to her husband’s long absences abroad with Philip. She would go on to have ten children with her husband. Her unusual portrait suggests that she went blind in one eye during her lifetime, but contemporaries only speak of her beauty, and it is unknown why she wore an eyepatch. Ana was also known to be quite religious, and she founded a convent in the town of Pastrana.

After her husband’s death in 1573, she continued to play an active role at court and developed a (politically motivated) friendship with Antonio Pérez, who was one of King Philip’s private secretaries. She was later accused of the murder of another secretary called Escobedo alongside Pérez, and they were arrested in 1579. She was initially imprisoned in a castle at Santorcaz before being moved to her family’s palace in Pastrana where she was confined to a suite of rooms.

Her youngest daughter, also named Ana, attended on her during her confinement. She was allowed on the balcony overlooking the square for one hour a day. It is unclear why the King was so harsh towards Ana.

She would die in those rooms on 2 February 1592. 1

The post Ana de Mendoza, Princess of Eboli – The one-eyed beauty appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 26, 2019

What makes a Princess and will Camilla be Queen?

After seeing the recent comments on my Facebook page, I decided to explain once and for all what makes a Princess in the United Kingdom and that oh so burning question, will Camilla be Queen?

The cause for all the comments was my article, “The Duchess of Cornwall – The vilified Princess“. The word Princess threw off a lot of people and immediately people said she wasn’t a Princess but a Duchess. Here’s the deal: Camilla became royal by marriage when she married The Prince of Wales. Her rank is that of a Princess of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. She is legally entitled to be called The Princess of Wales but has decided to use the lesser title of Duchess of Cornwall. Because she is not born royal, she is not entitled to be “Princess Camilla”. The late Diana, Princess of Wales, was commonly called “Princess Diana” but she was not entitled to this either. The same goes for The Duchess of Cambridge, the Duchess of Sussex and the Countess of Wessex. The 1917 Letters Patent limits the title of Prince or Princess to the children of the sovereign, the grandchildren of the sovereign in the male line, and the eldest son of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales. In 2012, this was expanded to include all the children of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales ensuring that both Princess Charlotte and Prince Louis were born Prince and Princess.

Does this make any of these women any less of a Princess? No. This was confirmed by Buckingham Palace when Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon married the Duke of York (future King George VI). They released this statement: “In accordance with the settled general rule that a wife takes the status of her husband Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon on her marriage has become Her Royal Highness the Duchess of York with the status of a Princess.”1 When Marie Christine von Reibnitz married Prince Michael of Kent in 1978, she became Princess Michael of Kent – sharing her husband status and taking on the feminine form.

This leads us to the next question, will the Duchess of Cornwall become Queen? You should remember that there are several types of Queens, most notably Queens Regnant (who rule in their own right, like the current Queen Elizabeth II) and Queens Consort (the wife of a ruling King). Prince Charles is the heir to the throne, and when Queen Elizabeth II dies, he will become King. Camilla – who shares her husband’s status – will take on the feminine form and become Queen. As she does not rule in her own right, she will become Queen Consort. Both consort and regnant Queens are “Her Majesty The Queen.” When Charles dies after becoming King, Camilla will become dowager Queen and be known as “Her Majesty Queen Camilla” to differentiate from the new Queen consort.

Do you have a question that you would like to submit to History of Royal Women? Email us at info@historyofroyalwomen.com or fill in our contact form here.

The post What makes a Princess and will Camilla be Queen? appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Charlotte of Prussia – The Princess tortured by ill-health (Part two)

In 1892, Bernhard and Charlotte moved to Meiningen until three years later when Bernhard was posted to Breslau. Charlotte enjoyed life at Breslau, and it was perhaps best to be away from her brother’s court for a while as her relationship with her sister-in-law was not at all good. The Empress soon learned that Charlotte intended to learn how to ride a bicycle, which she thought was “indecent.” Charlotte ignored her meddling sister-in-law. Charlotte soon found another court to entertain at – the Romanian court. She even helped to arrange the marriage between Marie of Edinburgh and Crown Prince Ferdinand. However, she managed to incur the wrath of the King of Romania when she tried to make sure her brother would never pay a state visit to Romania and so she was no longer welcomed in Bucharest either.

In October 1897, Feodora became engaged to Prince Henry XXX Reuss who was also 15 years older than her. Empress Frederick wrote, “It is of course not an advantageous marriage in terms of rank or position, but if Feo is happy, which she really seems to be, and the parents are satisfied, one ought to be glad.” Like Charlotte, Feodora was probably happy to escape her old life. They finally married on 24 September 1898 at Breslau. Feodora wore a white satin gown trimmed with myrtle and orange blossom and Venice lace. She also wore her mother’s wedding veil and diamond pins that belonged to Empress Frederick. The Emperor was notably absent from the wedding – he was still angry after Charlotte had been involved in yet another scandal. Shortly after their daughter’s wedding, Charlotte and Bernhard bought a villa in Cannes and Charlotte was soon spending most of the winters in France.

Charlotte continued to suffer from ill-health for most of her life, and although her mother attributed it to her excessive smoking, it is more likely that both Charlotte and Feodora suffered to some extent of porphyria – a metabolic disorder. From Charlotte’s late 30s the symptoms began to increase in severity. The relationship between Charlotte and Feodora also hit an all-time low in December 1900. Charlotte angrily wrote, “I could hardly believe that this curious, loud personage had been my child! I cannot love her! & My heart seemed & felt like stone.” She was convinced that Feodora’s husband Henry had poisoned her mind. Charlotte’s own mother was dying of spinal cancer, and she was by her bedside on 5 August 1901 when Empress Frederick passed away.

In February 1903, Charlotte and Bernhard celebrated their silver wedding anniversary at Kiel. Feodora was invited but no mentioned was made of her husband being present. In the summer of 1903, Charlotte wrote to her doctor that her nerves were “in shreds, although my appearance does not show it. But a terrible headache on one side & dizziness on the left side so depress me & completely irregular feelings of malaise, with a rash and itching,” She also had neuralgia over the left eye and had been vomiting pretty severely for several weeks. Her urine was also dark red. Doctors did not understand porphyria at the time and believed her symptoms were hysterical in origin. In September 1911, Charlotte wrote to Feodora after almost ten years. Feodora had undergone an operation in an attempt to deal with her infertility issues, but the operation had nearly cost her her life. Charlotte, never the maternal type, wrote, “You were ever a strong & healthy girl & all your internal organs were in perfect condition & order, so what has suddenly made yr (sic) inside go so wrong, I fail to comprehend or take in.”

In June 1911, Charlotte was one of the guests at the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary, and she spent several weeks in the country after the coronation. On 25 June 1914, Charlotte and Bernhard at last succeeded as Duke and Duchess of Saxe-Meiningen upon the death of Bernhard’s father at the age of 88. However, their accession came just days before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie. Bernhard was sent to the front while Charlotte remained behind. Charlotte became very ill during this time, and she suffered from kidney pains, boils and oedema. The only thing that remotely helped was morphine. When her brother-in-law Prince Adolf of Schaumburg-Lippe, the husband of her sister Viktoria, died in 1916, Charlotte was by her sister’s side, even though they had never been particularly close. By the end of 1917, Charlotte was practically unable to walk. When the war came to an end in 1918, Charlotte was basically confined to her bed.

Her brother Emperor William II had requested asylum in the Netherlands and abdicated on 9 November 1918, following by Charlotte’s husband the following day. To add to Charlotte’s health issues, she also began to have heart problems. In late 1919, she travelled to Baden-Baden to a clinic for treatment, but they could do nothing for her. On 1 October 1919, she suffered a heart attack and died. Her sister Margaret wrote, “My sister’s death was quite an unexpected loss. I had no idea how ill she was & she evidently thank God did not know it herself, for she was still full of plans & never alluded to anything in her letters. She must have suffered agonies & one can be but grateful that she was spared more pain & the end came so quickly & peacefully.”

Her husband survived her for six years, and he was laid to rest next to Charlotte at the mausoleum at Schloss Altenstein.1

The post Charlotte of Prussia – The Princess tortured by ill-health (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 25, 2019

Charlotte of Prussia – The Princess tortured by ill-health (Part one)

Princess Charlotte of Prussia was born on 24 July 1860 as the daughter of the future Frederick III, German Emperor and his wife, Victoria, Princess Royal. Her delighted grandmother Queen Victoria wrote to her daughter, “Thousand, thousand good wishes, blessings and congratulations! Everything seems to have passed off as easily (indeed more so) as I could have expected though I always thought it would be very easy, and the darling baby – such a fine child. I am delighted it is a little girl, for they are such much more amusing children.” Charlotte’s mother was quite proud of her daughter and wrote when she was three months old: “I am so proud of her and like to show her off, which I never did with him [her eldest son William] as he was so thin and pale and fretful at her age.”

(public domain)

(public domain)However, at the age of 21 months, Charlotte began to worry her mother with her violent tantrums. Charlotte was hyperactive, and her mother noted that “her little mind seems almost too active for her body – she is so nervous & sensitive and so quick.” Charlotte was soon turning out to be “a most difficult child to bring up, if she were not so stupid and backward, her being naughty would not matter.” Even Queen Victoria thought her daughter was being too critical of Charlotte and wrote to her to be encouraging and kind. Charlotte continued to display behavioural problems like sucking and chewing on her clothing and biting her fingernails. She was of a very small stature and still looked about nine years old when she was already well into her teens. She had “no taste for learning or reading, for art or natural history.”

Nevertheless, on 1 April 1877, Charlotte’s engagement to her second cousin Bernhard, Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Meiningen was announced. He was nine years her senior. Her mother could only hope that Bernhard would have a good influence on her wayward daughter and wrote to Queen Victoria, “Everyone is initially enthralled & yet those who know her better know how she really is – and can have neither love nor trust nor respect! It is too sad. There is nothing to be done, it is just a fact & one can only hope that time & life will serve as teachers to her & that the good Bernhard will protect & guide her. Then at least her wicked qualities will not be able to cause her any harm.”

Charlotte and Bernhard were married in a double wedding with Elisabeth Anna of Prussia (whose father was a younger son of Frederick William III of Prussia) and Frederick Augustus, Hereditary Grand Duke of Oldenburg on 18 February 1878 in Berlin. Her mother wrote that Charlotte “really looked very pretty – in the silver moiré train, the lace – the orange and myrtle and the veil.” The festivities lasted so long that Charlotte fainted three times from sheer exhaustion.

Charlotte and Bernhard moved into a small villa near the New Palace in Potsdam. Still feeling her mother’s watchful eyes on her, Charlotte and Bernhard travelled to Paris by the end of the year, and she soon realised that she was pregnant. On 12 May 1879, Charlotte gave birth to Queen Victoria’s first great-grandchild named Feodora Victoria Augusta Marie Marianne. Feodora was born just six weeks after the death of her mother’s 11-year-old brother Prince Waldemar of diptheria and Charlotte was deeply affected by his death. Though Charlotte’s dislike of her mother softened somewhat, their relationship remained difficult at best. Victoria did dote on young Feodora, she was, after all, her first grandchild. Charlotte herself found pregnancy limiting and declared that she would have no more children. Charlotte and Bernhard soon moved from Potsdam to Berlin where Charlotte drank, smoked and entertained. She was proving herself to be quite the gossip.

Queen Victoria first met her first great-grandchild when the eight-year-old Feodora accompanied her parents, grandparents and her aunt and uncle to the Golden Jubilee celebrations in London. Queen Victoria loved “little Feo” who “is so good and I think grown so pretty. We are delighted to have her, and I think the dear child enjoyed herself.” By then Charlotte’s father was already quite ill. When Charlotte’s grandfather Emperor William I died on 9 March 1888, her father – now Emperor Frederick III- was already left unable to speak due to throat cancer. He would die just 99 days later on 15 June 1888. Her elder brother William was now the new Emperor. Charlotte sought to integrate herself into her brother’s circle, but not many people trusted her.

Meanwhile, young Feodora was growing up in her grandmother’s household at Friedrichshof. The young girl was an only child and had very little contact with her cousins. By 1890, Feodora began to display the same type of health problems that continued to plague her mother. She was often ill, had diarrhoea and pain in her head, back and limbs. When Feodora was 13 years old, the Empress Frederick – as she was now called – wrote, “I find dear little Feo hardly grown, she is very plain just now, especially in profile – a huge mouth & nose & chin – no cheeks – no colour – the body of a child of 5 & a head that might well belong to a grown-up person!”1

Part two coming soon.

The post Charlotte of Prussia – The Princess tortured by ill-health (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 24, 2019

Jewels! The Glitter of the Russian Court Exhibition at the Hermitage Amsterdam

This autumn the Hermitage museum in Amsterdam is playing host to a grand collection of magnificent jewels from the Russian court with “Jewels! The Glitter of the Russian Court”

The exhibition contains 300 pieces of jewellery but also more than 100 paintings, accessories and dresses and other types of fashion.

I expected to be amazed by all the glittering jewels but unfortunately, this exhibition failed to wow me. A lot of the items belonged to nobles rather than royals and I expected more actual jewellery instead of the – most likely still quite expensive – snuff boxes and the like. In addition, the exhibition was absolutely packed with people despite the use of timeslots. Nevertheless, the exhibition is set up quite well, though a little bit more space would not have hurt in some areas.

Click here for more information about visiting the Hermitage and Jewels! The Glitter of the Russian Court exhibition.

Click to view slideshow.

The post Jewels! The Glitter of the Russian Court Exhibition at the Hermitage Amsterdam appeared first on History of Royal Women.