Omid Malekan's Blog, page 5

September 17, 2018

The Looming Existential Crisis for PayPal

A few years ago, PayPal made a splash by announcing that its users would be able to use the service to withdraw funds from Coinbase. It also put up a web page dedicated to extolling the virtues of blockchain technology. Crypto enthusiasts should look back on this moment with fondness, as it was a rare act of support from a payments industry famous for doing the exact opposite.

PayPal shareholders on the other hand should consider that moment with lament, as that was the moment when their company put its stamp of approval on the technology that will soon eliminate its reason for existence.

Of all the major companies in the cross-hairs of the BEEStMoD juggernaut, PayPal and fellow payment companies like Adyen and Transferwise are facing the most immediate threat. Not because cryptocoins are about to replace fiat money anytime soon (or ever), but because we are on the fast track to a world where payments are practically free.

All payments, in any currency.

I f that sounds hyperbolic to you, consider the case of the telephone industry. For most of the 20th century, charging people to talk on the phone was one of the most profitable businesses on the planet. Telco giants like AT&T made a fortune providing that basic service, until the Internet happened.

A telephone call is nothing more than an exchange of data — data that happens to be the human voice. In a world where everyone already pays for unlimited data via their ISP, it doesn’t make sense for them to pay extra for just one kind of data, not when they can get the same thing for free via Skype, Google Voice, WhatsApp or countless other alternatives. Today, Verizon Wireless, the biggest descendant of the AT&T monopoly, doesn’t even bother offering a voice-only plan.

Just as with a phone call, a payment is also an exchange of data, in one sense an even simpler exchange, because the instructions “pay Jane $5” contain less information than a conversation with Jane. But payments are a special kind of data, because security and consistency are of the utmost importance.

Until recently, the only way to ensure that security was through a series of intermediaries — banks, payment processors and the likes of PayPal — all of which took advantage of their position by charging fees. Those fees might look small on a per-transaction basis, but in aggregate add up to a massive tax on everything. The tax is so pronounced that it’s not unheard of for payment processors to make more money off the existence of an entire industry, like gas stations, than the industry itself.

Enter the blockchain. Despite the controversy surrounding the potential for cryptocoins to replace fiat money, one fact remains undisputed ten years after the invention of Bitcoin: the problem of fast, cheap and reliable payments without intermediaries has been solved. You can now send someone a payment as seamlessly as you would send them an email. You can make that payment in a cryptocoin, or you could make it using a tokenized version of your favorite central bank issued fiat currency.

As I’ve argued before, the first killer app on the blockchain might just be the US Dollar. The premise behind such products is as simple as that of PayPal. Some entity puts a bunch of dollars as collateral in a bank account, then issues tokens against them. As long as users are confident they can redeem those tokens for actual dollars, the tokens are free to be transacted quickly and cheaply on the infrastructure already built by BEEStMoD.

How cheap? A $1000 payment to a merchant using PayPal costs over $29. The same payment using a tokenized dollar riding the Ethereum platform today costs less than 20 cents. Not quite free, but a savings of over 99%. How’s that for disruption? Or an existential crisis for the $100b Wall Street darling that makes 90% of its revenues from transaction fees?

PayPal charges merchants both a percentage fee and a minimum per transaction fee, making it less competitive for large and small transactions alike. It also does things like tell its users what books they can’t read. Tokenized fiat money allows for greater freedom and anonymity for users, even if it’s not as decentralized as payments in crypto.

The only knock against products like Circle USDC, TrueUSD and Gemini Dollars is that their user interfaces tend to be a lot clunkier and harder to use than something as slick as PayPal’s Venmo service. But the history of payments tells us that users, and particularly merchants, are willing to go to great lengths to save on transaction fees, like when gas stations give you a significant discount if you pay via the clunkiest method of them all, cash. Once more companies start seeing the savings of tokenized fiat, better interfaces won’t be far behind.

One point I try to drive home in my book is that the great breakthrough of blockchain technology is how it gives digital items physical properties. Back when all money was physical, all payments were free. It wasn’t until the introduction of digital communication, and the inability of the thin protocols of the internet to handle value transfers, that charges on payments became a thing.

The first wave of such services were offered by the banks themselves, and not only were they expensive, but they were also slow and tedious. PayPal is a great solution to that problem. But blockchain technology eliminates the problem altogether — along with any need for a solution. Ironically, the newer payment processors face a greater threat from this tech than legacy banks.

Baby boomers who still like to write paper checks are probably never going to make the switch. But millennials who love Venmo will, especially once they find out that doing so will save their favorite coffee shop money, and do away with those annoying minimum requirements for paying with a card.

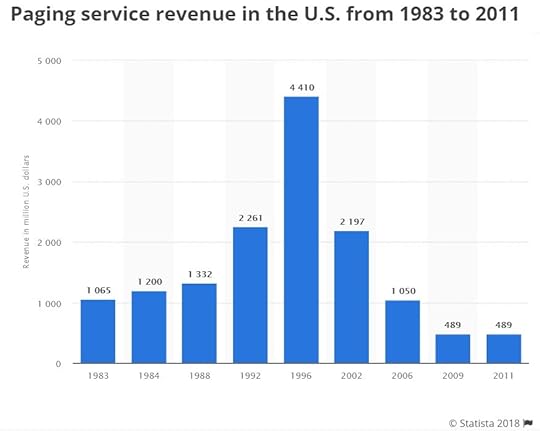

Being in the online payments business today is similar to being in the pager business in the 90s. Here’s a refresher:

Like every other tech driven revolution, this one will also create new opportunities for legacy companies. Banks can benefit by handling the collateral on these tokens (and keeping the interest income for themselves) and companies like PayPal might be able to offer slick front ends or services like KYC.

But a stock doesn’t trade at 50 times trailing earnings because it might get to provide incremental service. It does that because the market expects digital payments to grow exponentially, and for PayPal to be a major beneficiary. The market is correct about the former, but wrong about the latter. With PayPal stock trading near all time highs and up 50% in the last 12 months, now is the time to sell.

I’m already on the record forecasting that in five years, BEEStMoD will significantly outperform FAANG. With PayPal, I’m reducing that time frame to two. Unlike an Apple that makes hardware or an Amazon that has a retail operation, PayPal does nothing but charge for a service that will soon be disintermediated and free.

If you own the stock, I recommend getting out now, or at least hedging your position with the coins of the platforms that will soon render the company irrelevant.

September 6, 2018

As Prices Crash, Don’t Trust the News

People who are new to markets or don’t spend a lot of time interacting with them usually assume a simple causality where news dictates price, as in “bad news came out, so the price went down.” But spend enough time around markets, and you’ll realize that the opposite could also happen, especially in shorter time frames. There, it’s just as likely that price dictates news.

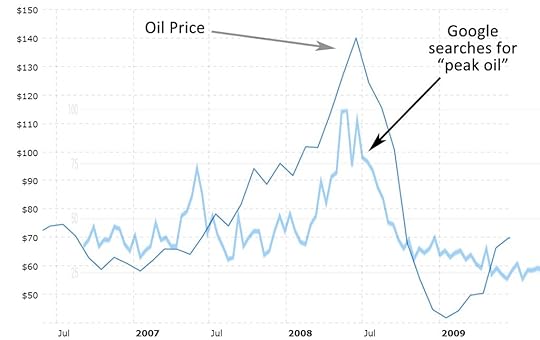

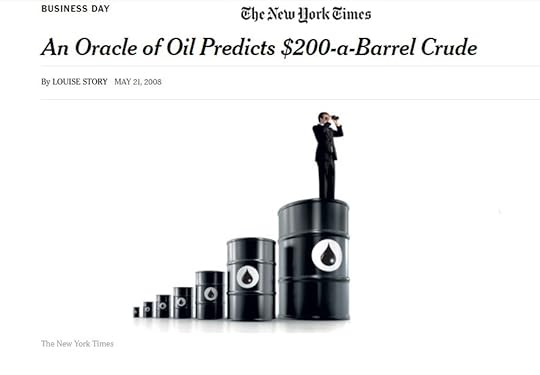

For a simple example of this phenomenon, consider the oil bubble and crash right before the financial crisis. During the bubble phase, when the price of crude climbed from $60 to $150, there was a constant stream of news articles on “peak oil” — the belief that we were nearing max global production. But when the price crashed all the way down to $30, mentions of that topic almost entirely disappeared. Here’s a chart of google searches during that period vs. the price of oil.

How do we know that it was price dictating news? Because actual oil production during that period barely changed.

This tail-wagging-the-dog phenomenon has been present in crypto markets from day one. There was no shortage of bullish news in December, and there is no shortage of bearish analysis now. Since price determines news, then the great crypto winter of 2018 necessitates a strong dose of bad news. Since Ethereum has fallen harder than Bitcoin, then it generates even more negative news flow than it’s older sibling. The more ETH falls, the worst the news and analysis gets. First it was a shitcoin headed to sub double digits, and now it’s so economically flawed that it’s going zero.

The latter hit-piece on Techcrunch is so egregiously flawed that I can’t help but respond. You can tell that it’s the kind of thing written by someone who has an ax to grind from it’s very first sentence, because it predicts an impossible outcome:

Here’s a prediction. ETH — the asset, not the Ethereum Network itself — will go to zero.

On any public blockchain, the value of the native token is a key component of its security. If the value of ETH goes to zero, then the Ethereum platform becomes exposed to all array of attack, the least hostile of which would be an endless stream of spam transactions.

Now, I’m guessing the author would argue that this wouldn’t be a problem, because in his fictitious universe, not a single miner would accept ETH to process transactions anymore, so all these spam transactions would just linger in the mempool. But if that were to happen, then there would be no Ethereum blockchain anymore. Instead, there would be thousands of independent forks, each using an ERC-20 token as it’s native coin, and each being also vulnerable to spam attacks, because the value of a single token on its own chain is always lower than the value of all tokens and a native coin on a single chain.

So, just knowing that this author claims “Ethereum ends up succeeding wildly but ETH becomes worthless” tells me he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. It’s the equivalent of someone predicting that house prices are going to soar, but you’ll be able to rent one for free.

When price determines news, extreme opinions spread like wildfire, aided by the fact that everyone is too distracted by what they see on their quote screen to realize when an analysis is full of unsubstantiated assumptions. Peak oil, for example, assumed that demand can’t ever go down and supply can’t ever go up. The financial crisis and the fracking boom made a fool out of anyone that believed either.

Jeremy Rubin’s entire argument is predicated on the assumption that in the future, all dApp users and all Ethereum miners will only want to pay for transaction fees using a token, leaving no other source of demand for ETH. This is a wild and unsubstantiated assumption, and there are many scenarios where it wouldn’t be true.

For one, any user who is bullish on the tokens they are using would much rather pay gas in ETH. Why? Because nobody likes to spend currency they think will go up in value. So long as a user believes that their tokens will appreciate in value more than ETH (something that virtually every single ICO participant who sent in ETH in exchange for a new token must have believed) then they will prefer to pay fees in ETH.

More importantly, why would the miners prefer to get paid in tokens? Put yourself in their shoes for a moment. They are spending hard earned fiat on hardware and electricity to earn a profit. As payment, they can either collect one cryptocoin — which happens to be the second most liquid digital asset in the world and traded at every major exchange — or dozens of different tokens, every single one of which is by definition less liquid than ETH, many of which don’t trade in every country, and most of which cannot be traded directly for fiat. Remember, the power company won’t let you pay the electric bill with a shitcoin.

Rubin addresses this argument (previously made by Vlad Zamfir) then dismisses it by claiming the process of cashing out countless tokens is no different than doing it for a single coin. But that’s like saying a coffee shop that accepts only dollars does the same amount of work as one that accepts dollars, euros, cans of beans, Bitcoins, purple crayons and sneakers signed by Kanye. The accounting alone would be a total fucking nightmare. This is why we don’t live in a barter economy anymore. It’s always easier to have everyone transact to one currency.

When it comes to markets, liquidity trumps almost everything. That’s why the vast majority of fiat currency trades around the world are done to just a few reserve ones, and why right now, in back alleys in Tehran and Buenos Aires, people are trying to trade their local money for dollars. That in turn explains how the US Dollar has managed to retain its value despite a decade-long campaign by the Fed to destroy it.

Being a reserve currency is extremely valuable, and ETH is the reserve currency of all ERC-20 tokens, a fact obvious to anyone who’s participated in an ICO on that platform. But Jeremy Rubin must not know what an ICO is. If he did, he would realize that his argument has already failed. It’s impossible to have a world where ERC-20 tokens are in demand and ETH is worthless, because to get to that point, every project would have sold their token to buy ETH.

Lastly, this farcical argument also assumes that the only natural demand for ETH is to pay the gas fee for transacting a token. This is a common argument made by Bitcoin maximalists, who’ve perhaps seen one too many Highlander movies, and love to remind the rest of us that when it comes to a purely digital stores of value or mediums of exchange, “there can be only one.”

This is an unsubstantiated argument, and it also ignores the many uses of the Ethereum blockchain that cost gas but have nothing to do with an ERC-20 token. When I teach my hands-on blockchain training course, I walk all my students through the process of purchasing an ERC-721 token. How, pray tell, does one buy a Cryptokittie and not use ETH to pay the gas fee? I’ve never actually bought one, but I’m assuming you can’t just send the miner your cat’s tail.

Beyond non-fungible tokens, you would also have to use ETH to pay for gas if you wanted to use Ethereum to circumvent government censors, store a hash of your digitally executed document or have your permissioned blockchain reconcile to a public one.

I have no idea who Jeremy Rubin is, nor do I really care. What I do know is that he’s not really out to make a compelling argument. I knew that about him before I even read his post, because its title has the word “inevitable” in it. If there’s one lesson we’ve learned over and over on this brand new frontier, it’s that nothing is inevitable.

To state otherwise is to be ignorant of the many unknowns and unknowables before us, which is why the kind of person that would make such an argument is at best a fool and at worst a provocateur, exploiting the current wave of negative sentiment to get a faulty point across.

Ethereum might very well go to zero someday, or it might flippen and go to the moon. But as it bounces around trying to find it’s way, we should be careful about which ideas we consider because they are humble and coherent, and which ones are just a consequence of price driven frenzy, and are best ignored (I’m looking at you, Vitalik).

September 4, 2018

The BEEStMoD Manifesto

M y recent essay encouraging investors to rotate from the shares of FAANG to the coins of BEEStMoD turned out to be one of the most widely read and controversial things I’ve ever written. The reaction, which ranged from bemused to angry, confirmed my impression that most people simply can’t imagine a world where corporations don’t dominate their digital lives. To see why it’s possible, consider the following — even more unlikely — scenario:

Imagine a world where a handful of people invented a technology that created trillions of dollars in economic value, but that the inventors didn’t make a penny off of it. Instead, the people who used this technology to make a far less important economic contribution made a killing. It would be as if Edison and his lab made nothing from the lightbulb, but a random seller of quirky lampshades became a millionaire.

This shouldn’t be hard to imagine, because that’s the world we live in today. Tim Berners-Lee, the man who gifted us the World Wide Web, made less money off of his creation than Rebecca Black, the teenager who gifted us that famously awful YouTube video. Your average Instagram influencer probably makes more money off the internet than all of its founding fathers, combined.

To be fair, my lampshade analogy isn’t fully accurate, because Black didn’t make as much on her video as YouTube did. A better analogy would be if Edison made nothing, the lampshade designer made a little, and the shipping company that delivered the lampshades became a Fortune 100 company.

Our digital economy today is such that those who invented its underlying infrastructure, and those who create the content that makes that infrastructure appealing, capture less economic reward than the middlemen. Without TCP/IP and HTTP there’d be no search engines, and without interesting websites there’d be no reason to use search. Google is arguably the least important component of this triangle, yet it makes almost all of the money.

So before you tell me that it’s hard to imagine a future where highly profitable intermediaries like Google and Facebook don’t exist, consider that it might be even more implausible that they do.

None of this is anyone’s fault, per se. The protocols that make up the internet wouldn’t have worked if their creators had tried to monetize them. As Berners-Lee himself said: “If I had tried to demand fees … there would be no World Wide Web..There would be lots of small webs.”

And so, TCP/IP, HTTP, SMTP and various other protocols were just given away. The existence of these so called “thin protocols” — as so elegantly coined by Joel Monegro — is what made the rise of the “fat applications” of FAANG possible. At the time, their creation was a blessing, because a bad economic model is always better than no economic model. But today, that model has turned into a problem.

I n economics, any system where risk and reward are out of alignment is inherently unstable. A party that can capture almost all of the reward while taking none of the risk (thus having no Skin in the Game) is going to press its luck until something breaks. For a perfect example, see the 2008 financial crisis, which we can now summarize as the inevitable outcome of what happens when bonuses flow to one group while burdens to another.

Such is the state of FAANG & Company today. On any given day, millions of people take on the risk of publishing a song, driving an Uber, making a YouTube video, renting out an AirBnB, building a Twitter following, publishing a book or posting interesting content on Facebook. When they fail, which the vast majority inevitably do, they take home 100% of the loss. But should they succeed, a giant corporation that already has more money than it knows what to do with takes a massive cut. No wonder the tech giants are starting to eat themselves.

Just recently, Apple’s iTunes store booted an app owned by Facebook because it was a spying tool masquerading as a privacy one — proving once again that Facebook has no shame (the deceptive app literally had the word Protect in its name.) You would think that Mark Zuckerberg would have learned his lesson by now, but then again why should he? Your risk is always his reward. (Apple at least seems to have done the right thing, but perhaps only because the victims weren’t Chinese.)

There are many political and technological explanations as to why these companies keep stumbling from one controversy to another. My contention is that the problem is primarily economic. When risk and reward are not aligned, two outcomes become increasingly likely:

The beneficiaries make a shitload of money.The beneficiaries make bad decisions.Welcome to FAANG 2018.

The decentralized platforms that comprise my BEEStMoD index bring that relationship back into alignment. Blockchain technology allows us to replace corporate intermediaries with a decentralized platform that is owned and governed by its users. The benefits start with the financial — as taking out the middleman usually does — but go far beyond into the social and cultural. Consider payments as an example.

If you use PayPal for your company, then not only do you have to pay a hefty fee, but you also risk having a central authority tell you how to run your business. If you use it as a consumer, you face higher prices (as the fees get passed on to you) as well as a corporation dictating what books you shouldn’t read. But if you use Bitcoin, Ethereum or even a tokenized dollar, you take back control of your financial (not to mention literary) life.

I t should be noted that switching from FAANG to BEEStMoD doesn’t diminish user risk, it increases it. On a decentralized platform, not only does each cab driver or social media influencer still have the risk of losing to other cab drivers and influencers, they also shoulder the risk of their chosen platform failing, akin to employees at a startup getting some of their compensation in equity that might end up worthless.

But a stable economic system isn’t one with no risk. It’s one where rewards are handed out proportionally. Just as the risks are higher with BEEStMoD, so are the rewards. On a decentralized platform, not only can a cab driver or influencer earn more by beating the competition, they can also become wealthier if their chosen platform gains popularity, thanks (in part) to their own contribution. This — far more equitable — flow of value yields yet another reason why the world would be a better place if the biggest digital platforms were decentralized.

The ascension of FAANG & Co has been a major contributor to the growing wealth gap. While almost anyone can post a video on YouTube, virtually no one can afford the $1200 it costs to invest in a single share of its parent company, thus ensuring a constant flow of wealth from average citizens to a handful of billionaires. BEEStMoD realigns this relationship entirely, ensuring that the earliest adopters of a platform, and the people who make it appealing to others, benefit the most, as has already been the case with Bitcoin.

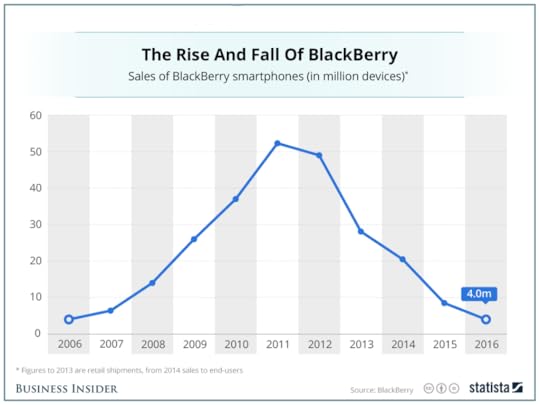

I understand that all of this seems unlikely. But the technological graveyard is filled with companies and platforms whose dominance once seemed permanent. It wasn’t that long ago when many of us couldn’t imagine living without AOL Instant Messenger, a platform that as recently as 2006 enjoyed greater than 50% market share in North America. Today, it doesn’t exist. When it comes to technology, the switch from the unlikely to the inevitable can happen in an instant, and if you wait until the writing is on the wall to adjust your investment portfolio, you’ll be too late.

Now is the time to sell FAANG and rotate into BEEStMoD.

Disclaimer: I’m a user of both FAANG and BEEStMoD, making me a value contributor for both, and an equity holder for one.

August 19, 2018

Select Observations on the State of Crypto Markets

Two important things happened in crypto-land over the past few weeks. The first, which you probably heard about, was yet-another-crash in prices to new cycle lows. The second, which I consider more important, was that while market caps fell apart, the trading infrastructure did not.

It wasn’t that long ago when every major market move resulted in exchanges crashing and wallet services slowing to a crawl. The problem was so pronounced that it made most traditional trading strategies useless, because you couldn’t access the market when you needed to. Anytime a friend asked me if the latest selloff was a good time to get in, I would joke that they shouldn’t buy “until you see the white’s of their CloudFlare errors.”

These problems were understandable, because crypto companies have to commit an extraordinary amount of their resources to security. The New York Stock Exchange doesn’t have to worry about someone penetrating their servers and stealing a bunch of Disney stock, so it can focus on stability and usability. Crypto exchanges on the other hand are the world’s greatest honeypots, so capacity and UI have always taken a backseat.

The lack of major outages during the recent decline shows capacity has caught up with demand and liquidity has improved. We’ve come a long way from traumatic events like this one, and that’s an important accomplishment.

Most people only care about the price of crypto assets, but the reliability of the infrastructure is arguably more important. A good market isn’t one that only ever goes up, it’s one that clears smoothly in both directions. My overarching theory that decentralized platforms will eventually overtake their corporate counterparts requires reliable markets to pan out.

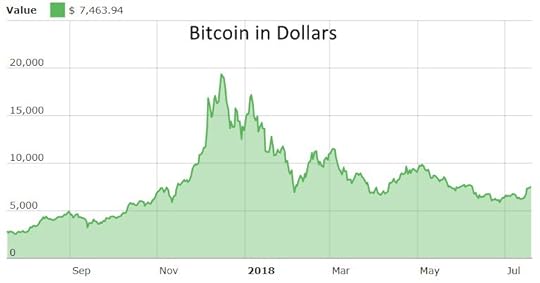

As for the question of why prices have fallen so dramatically in 2018, the simplest answer is “because they went up too much in 2017.” I’m generally skeptical of after-the-fact market explanations, but since it’s fun to speculate, I’d like to consider two possible explanations for why the selloff has accelerated of late.

The first is yet-another-rejection of a Bitcoin ETF by the SEC. To gauge the importance of this news, it helps to quantify the potential demand for such a product. For that we can look at the only other dollar-denominated “equity-like”product that Americans can buy, the Grayscale Bitcoin Investment Trust (GBTC).

This product doesn’t trade on any major exchange, and has not passed nearly as much regulatory scrutiny as more popular investment trusts like the one for gold, so a lot of brokers won’t let individuals buy it and most institutions are not legally allowed to own it. Despite those constraints, GBTC manages to trade at a 40% premium to the Bitcoins it claims to own.

This kind of disparity between the price of the shares of a trust and the value of the asset it owns usually implies that demand for the underlying asset is so strong that investors are willing to overpay to own it. That conclusion is further validated by the fact that back in December, when the price of Bitcoin was really soaring, the premium was over 100%. That it remains as high as 40% despite the current crypto winter tells us that there is still a significant amount of money wanting to find its way into crypto that can’t. A fully regulated ETF would help alleviate that problem.

The second possible reason why crypto has been falling has to do with the biggest crypto traders on the planet. And no, I’m not talking about whales, miners or assorted Bigfoot-cum-Tether-toting boogiemen. I’m talking about project developers.

All of the ICOs that raised billions of dollars last year got paid in Ether, a currency that they could not use to rent office space or pay their staff. This put the leaders of such projects, most of whom probably had little market experience, in the awkward position of having to figure out when to sell, and how much.

The responsible approach, given their cash requirements and the volatility of crypto assets, would have been to sell some of their ETH immediately and to keep selling as ETH went parabolic. But Ether was the best performing asset on the planet in 2017, and nobody wants to sell something that seemingly only goes up.

Until it starts going down. There is a theory floating around that the current bear market is at least partially caused by ICOs panic-selling into the decline. It’s substantiated by the fact that ETH has fallen more than most other coins, and some anecdotal data. I would add a third piece of evidence: human nature. The great bull run of 2017 even fooled experienced traders. We can hardly blame project developers from falling into the same trap.

The volatility of this space continues to be perpetuated by the fact that there are still no widely agreed-upon valuation metrics, no P/E ratios or Net Present Values to help investors make decisions. The only piece of information anyone has is price, and price is a self-perpetuating metric. It makes people want to buy when something is going up and sell when it’s going down.

Investors and project leaders would be well served to remember that the next time the market shoots for the moon.

My book, the Story of the Blockchain: A Beginner’s Guide to the Technology That Nobody Understands, is available on Amazon

August 12, 2018

The Case for Selling FAANG and Buying BEEStMoD

I’ve already written about how the trend towards decentralization is going to change the nature of investing, but that was before Facebook’s stock took a historic pummeling on account of bad earnings and Apple became the first trillion dollar company on account of good. The violence of both moves set off my ex-trader’s spidey sense that this might be the kind of volatility that precedes a change.

Markets are devious, and love sucking everyone into a particular investing thesis right before proving it wrong. In the year leading up to the financial crisis, bank stocks were soaring (because home prices could never go down) and the price of oil was spiking (because supply could never go up). The housing crash and fracking boom swiftly proved otherwise.

Today, it’s almost impossible to imagine a world where the FAANGs — Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google — aren’t dominant. That’s why it’s a good a time to start selling, and diversifying into the decentralized platforms that will eventually replace them.

I know that this is a bold and seemingly hyperbolic statement, and I usually prefer not to give investment advice. But this particular setup is too sweet to ignore, so bear with me as I lay it out.

Companies like Facebook and Google get a lot of criticism for being too big, but that’s a political opinion, not an investment thesis. Dominance might be bad for society, but it’s good for business. The better reason to sell is because the fundamental structure of those companies is slowly becoming obsolete.

Their kind of corporate structure made sense during the industrial era, when you needed a centralized hierarchy to deliver complex durable goods like a car. It still made sense as we transitioned to the service economy, because branding and a homogeneity of experience mattered. But the model that work for GM or McDonald’s doesn’t work for a digital platform, because it leads to a misallocation of resources.

Think about the difference between a privately owned fleet of taxis and Uber. A fleet can enjoy economies of scale by raising capital, buying cars, having its own repair shop, and so on. Uber doesn’t do any of that. It just provides a convenient platform for drivers (who have their own cars and pay their own mechanics) to be hired by users.

So Uber is not a taxi company. It’s a platform for countless little taxi companies, each of which has to do all the work AND take all the risk. And yet, Uber still takes as big of a cut as a traditional fleet operator.

But hey, at least Uber still pays most of the revenues to its drivers. Companies like Facebook and Google pay virtually nothing to those doing the heavy lifting. Somehow, even though it’s their users that invest resources to create their content, the platform ends up capturing most of the profit. A video like Psy’s Gangnam Style clearly required a heavy investment of time and money to make. If it had been a dud, the failure would not have cost YouTube a cent. So why did Google take most of the profit when it turned out to be a hit?

All social media platforms — not to mention the iTunes ecosystem and Amazon’s digital services — have an asymmetric risk/reward profile, so it’s worth asking why we as users put up with them. The answer, until recently, was because there was no other way.

The internet has lacked a proper business model from day one, as anyone who worked in the music business 20 years ago could attest. Today’s centralized platforms were the first solution to that problem. We can criticize iTunes for the paltry fees it pays musicians to stream their music, but it’s still an upgrade over Napster.

The mistake was forgetting that this was only a temporary solution. A system where a large corporation captures almost all the value created by users is not good for anyone — except shareholders. A decentralized platform solves this problem, because the platform user and owner become one. There is still plenty of risk, but at least the rewards now go to those who deserve it, as has been the case with the first economically viable decentralized platform.

Bitcoin is different things to different people, but technologically, it’s just a decentralized content platform — for payments — that’s worth over $100b. Miraculously, all of that value is captured by its users. There’s no Bitcoin Inc. benefiting from someone else’s foresight.

That model of decentralization is now being applied to every other kind of content company out there. To me, it’s not a question of whether such platforms will eventually cannibalize today’s centralized counterparts. It’s a question of which, and when.

Which brings me back to your FAANG stocks. Even if you aren’t ready to sell, I recommend hedging your investment with a small investment in their decentralized counterparts, each of which is represented by a coin. If you don’t know which coins to invest in, then allow me to introduce you to BEEStMoD: The two Bitcoins, Ethereum, EOS, Stellar, Monero and Dash.

These coins represent the most important blockchain projects being developed today. Most of them focus on decentralized payments, cloud computing, or some combination thereof, which makes sense, as those are the two pillars of any successful online platform.

As an added bonus, you can currently buy into these platforms at recent lows, while selling your FAANGs near all-time highs. My two cents (or Satoshis) have at times cost others a lot more than that, but I’m confident that five years from now, $10,000 invested in BEEStMoD will have done much better than the same money invested in FAANG.

In fact, I’m willing to bet on it, and to do so publicly, buy doing the very technology I recommend investing in. In my next post, I will describe how.

July 27, 2018

Coins vs. Companies

What does Ken Griffin, one of the world’s greatest hedge fund managers, not get?

Back on July 18th, the Citadel founder joined the now-cliched ranks of other Wall Street luminaries who have knocked cryptocoins. The takeaways:

If you are a trader, you may have found another great buy signal. Bitcoin was trading below $5000 when Jamie Dimon called it a fraud last year. By the time he changed his tune, it was over $15,000.

Fade the Famous Finance Guy has been a statistically significant trading strategy.

If you are a Wall Street skeptic, you can assume Citadel is working on a major blockchain-based product. J.P. Morgan was deep into developing Quorum when Jamie went on the attack.

Don’t Trust the Famous Finance Guy has been a statistically significant business strategy.

If you are a technologist, you could use see this as a teaching moment. Ken Griffin is one of the most successful American businessmen of the past 20 years, having built his firm from nothing to a financial powerhouse. And yet, even he doesn’t understand the economic transformation slowly unfolding underneath our feet.

It’s not his critique of Bitcoin as a currency that’s revealing — whether a pure cryptocoin can ever become a viable medium of exchange is still an open question — but the way he rejected owning a coin over investing in a company. Specifically:

“I wish the 27 year old wasn’t buying Bitcoin. I wish they were investing in companies that define the future of our country, and pushing capital in a way that will create jobs, create innovation and grow our economy”

What Griffin doesn’t understand is that in the decentralized world to come, the coin will be the best way to invest in the future, because the platform will replace the company.

What, exactly, is Bitcoin? There are many answers to that question — some more controversial than others — but the simplest technological definition is “a payment platform.”

What is that platform worth? As of this writing, around $135b

So who owns it?

Nobody.

The closest thing to an owner, in the traditional sense, are the coin holders. Owning bitcoins is the only way to capture any of the value of the Bitcoin Blockchain.

Welcome to the decentralized business model of the future.

Griffin, along with other famous crypto skeptics like Jamie Dimon and Warren Buffet, are among the most successful members of the old, almost industrial way of doing things. In that model, a company offered a product or service. If consumers liked it, then value accrued to the shareholders. This was Business 1.0, later replicated to also be Web 1.0, because the first business model of the internet was predicated on this centuries-old way of doing things.

Next, after the rise of the information economy, came Business or Web 2.0, led by more contemporary CEOs like Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg. Here, instead of offering a product or service, the company’s contribution was to create a proprietary platform. If consumers liked that platform, they would use it to generate much (if not all) of the content. Value still accrued to the shareholders.

We are now on the cusp of Business and Web 3.0. Thanks to the disintermediating force of a blockchain, the creator, consumer and shareholder are about to become one, with their interaction regulated by a token or cryptocoin. On the outside, the look and feel of most platforms will not change. A decentralized social media or cloud computing platform won’t look very different from Facebook or AWS. But should they succeed, the value will accrue back to the users, because they are the coinholders.

You can see this phenomenon already in effect with decentralized platforms like Bitcoin and Ethereum. As the value of their coins fluctuates with the perceived value of the platform, so does the bottom line of everyone involved, from miners to developers to users to speculators.

***

To be fair, the three economic models above are not as discrete as I made them seem. Some proprietary platforms, like YouTube or Amazon, do share a portion of the revenues with content creators. But until recently, we’ve never had a mechanism where all of the upside — not to mention risk — could be captured by users.

The basic investment principles of risk vs. reward will never change. Platforms, whether proprietary like Facebook or decentralized like Ethereum, tend to have winner-take-all tendencies. So the ones that succeed will deliver exponential returns to coinholders, while the ones that fail (as countless blockhcain projects already have) will result in total loss.

Nevertheless, and to paraphrase Ken Griffin, in the future, buying the coin will be the primary way to push capital in a way that will lead to innovation, create jobs and push the economy forward. If you want to participate, best get in now, before Citadel changes its mind.

July 20, 2018

Stablecoins

I know very little about the family of projects known as “stablecoins” — cryptocoins designed to address the volatility of blue chip coins like Bitcoin. Mine is a state of willful ignorance, as there’s something about a coin designed to be price-stable, like Maker’s Dai, that has never sat right with me.

But that’s not a good enough reason to dismiss a project, so today I am going to do a deep dive into why I don’t like these projects.

My problem starts with the very name of the category, as it’s a bit deceiving. In economics, there is no such thing as stable, not on an absolute basis anyway. All financial value is relative, in the same way that in space, all motion is relative.

To demonstrate what I mean, consider the question “what has the value of Bitcoin done so far this year?” We can’t answer that question until we introduce a denominator. If we are measuring value in dollars, it has fallen significantly. But in Venezuelan Bolivars on the other hand, it’s done much better.

source: cryptocompare.com

source: cryptocompare.comWhen we call something a “stablecoin,” what we really mean to say is “stable against fiat currency.” That’s an important distinction, and also a clue as to why these products were invented in the first place. No matter how great the underlying blockchain technology of cryptocoins like Bitcoin and Litecoin, their function as a medium of exchange has been hampered by their volatility.

The problem is made even worse by the fact that not only are the coins volatile against fiat money like the Dollar, but they are even more volatile against each other. If you’ve owned Litecoin over the past year, your coins have either halved or doubled in value — depending on whether you are comparing against dollars or bitcoins. You can’t use a currency like that in your day to day affairs.

Stablecoins are meant to solve this problem by combining the decentralized infrastructure and transparency of a blockchain with the more palatable price volatility of fiat money. A more accurate name for them would be “Dollar-pegged coins.” Here’s a description of Dai from its website:

“Dai is a cryptocurrency that is price stabilized against the value of the U.S. Dollar”

And Bitshares:

A SmartCoin is a cryptocurrency whose value is pegged to that of another asset, such as the US Dollar or gold.

So far, so good. I’ve already written about how I think the Dollar might be the next killer app for blockchain tech. So why don’t I like the projects listed above? Because they introduce complicated mechanisms to try to make a cryptocoin look and act like the Dollar. But you know what else looks and acts like the Dollar? The Dollar.

Tokenizing actual dollars is a simple process. First you put a bunch of them in a bank account as collateral, then issue tokens on a blockchain corresponding to each one. As long users are confident that they could redeem their tokens for actual dollars, the value stays at close to $1.

Creating stablecoins that are pegged to the Dollar, on the other hand, is far more complicated. Here again is Bitshares:

SmartCoins implement the concept of a collateralized loan and offer it on the blockchain. For the purpose of this discussion, we will assume that the long side of the contract is BitUSD and that the backing collateral is BTS (the BitShares core asset). To achieve this, SmartCoins use the following set of market rules:

1. Anyone with BitUSD can settle their position within an hour at the feed price.

2. The least collateralized short positions are used to settle the position.

3. The price feed is the median of many sources that are updated at least once per hour.

4. Short positions never expire, except by hitting the maintenance collateral limit, or being force-settled as the least collateralized at the time of forced settlement (see point 2).

Good luck getting people to use that coin to buy coffee.

Critics of tokenized fiat money argue that its simpler approach creates two centralized sources of failure, one in the bank that holds the collateral and another in the tokenizing entity. They are absolutely right, as we’ve seen time and again with Tether. But risk, just like value, is a relative concept. The question is not whether tokenizing fiat money in a centralized manner is risky. It’s whether doing so is more risky than a far more complicated decentralized approach.

I would argue not, because we are talking about money.

Complicated structured products are an important part of traditional finance, and the stablecoins mentioned above remind me of them. I mean that as a compliment, because both Dai and BitUSD strike me as sophisticated products created by intelligent people. But therein lies the problem.

Money is not supposed to be sophisticated or intelligent. It’s mostly a made-up thing, a myth that we all agree to subscribe to, because it serves a useful function. The US Dollar is not the world’s reserve currency because the Federal Reserve manages its supply using a modified Taylor Rule tied to the CPI. It’s the world’s reserve currency because ever since winning the second world war, America has loomed large in the global imagination, not to mention in trade, finance and pop culture.

The other reason people use the Dollar is because compared to other currencies, it is very stable. A lot of that stability stems from the fact that people expect it to be stable, and price volatility (or the lack thereof) is a self-fulfilling prophecy. That doesn’t mean that a central authority can’t destabilize the Dollar eventually, and if history is any guide, it’s only a matter of time until they do. But for now, its value is stable and its acceptance is ubiquitous, making it a great candidate for a global digital medium of exchange.

So instead of trying to reinvent the Dollar, let’s just tokenize it.

The markets, for what it’s worth, seem to agree with that conclusion. I find it telling that despite all of the controversy surrounding Tether, the market cap of its tokenized dollars is currently 20x more than the highest valued stablecoin. If we look at acceptance at crypto exchanges, the gap is even bigger. We can assume that a more trustworthy version of the same product (be it from Circle or these guys) will be even more popular.

That’s not to say that the various stablecoin projects out there are useless. I think the kind of decentralized structured products they empower might someday revolutionize institutional finance and the global derivatives market. But I wouldn’t be surprised if the first generation of those products still use tokenized dollars to settle their transactions. Money is a myth, and the arc of a popular myth is longer than any technological cycle.

Omid Malekan is the author of The Story of the Blockchain: A Beginner’s Guide to the Technology That Nobody Understands

July 13, 2018

The Next Killer Application on a Blockchain Might Be the US Dollar

A lot of the enthusiasm for Bitcoin comes from what differentiates the cryptocoin from traditional money, like its fixed inflation schedule and lack of a central bank. But if you go back and read the original white paper that gave birth to it, it’s not clear that those characteristics were the primary reason why it was invented in the first place.

The paper’s title, for example, only references a system of cash, and there is no mention of inventing a new currency anywhere in the abstract, introduction or conclusion. Instead, the author’s focus is almost entirely on the mechanics of digitizing money, with the hope of creating a “peer to peer electronic cash system.”

Almost a decade later, the Bitcoin blockchain has been so successful at delivering on that promise that the next killer application to start using the same technology might be the U.S. Dollar.

That idea is anathema to the more ideologically minded members of the cryptocoin community, but makes plain sense for the average person. When it comes to money, most people and businesses just want a currency that’s stable, widely accepted and cheap and easy to transact. The dollar has been pretty successful on the first two fronts, but has not kept up with the digital age when it comes to payments.

Bank wires and ACH transfers are still rather slow, and credit card processing fees rather high. Even the more modern payment services like PayPal and Venmo are not as efficient as they could be, partly because they are built on top of aging bank infrastructure. Satoshi Nakamoto’s great innovation of replacing large financial intermediaries with a decentralized ledger that’s continuously updated via a transparent consensus mechanism can greatly improve how fiat money like the dollar moves.

And in fact, it already has, as today there are multiple blockchain-based “tokenized Dollar” products available for use, offering an experience very similar to that of transacting Bitcoins or Ethers.

For those that are not familiar, these products are created by private companies who deposit dollars into a bank account, then issue tokens on a blockchain corresponding to each one. So long as users trust that they can ultimately redeem their tokens for real dollars, the value of each one stays around a buck. In the meantime, the tokens can be used online for all sorts of transactions, quickly and at minimal cost.

The idea is similar to ETFs in the stock market that track the value of other assets, like treasury bonds or gold, but is in some ways superior, as tokens on a blockchain move around more freely than ETFs siloed at a single exchange. And since the consensus mechanism of a blockchain replaces multiple banking intermediaries, transactions that used to take days to settle can now do so in an hour.

Tether USD, the most popular such product in the world today, currently boasts a market cap north of $2B. Most of the demand for its tokens comes, ironically, from cryptocoin traders. Since many of the world’s crypto exchanges have no ties to the banking system, a product like Tether’s is the easiest way for people to trade from dollars to cryptocoins, and vice versa.

A similar use case exists on Wall Street, where the main bottleneck in complex financial transactions is often the dollar payments needed to finalize them. Although there is a lot of hype about how blockchain technology could someday revolutionize the actual trading for such products, using it to speed up their payments is the lowest hanging fruit.

IHS Markit, the biggest player in the trillion-dollar syndicated loan market, has recently announced the creation of its own tokenized dollar product to help simplify the complex back and forth cash transactions that loans traded on their platform generate. A dozen token transactions on a blockchain are far easier to execute than a dozen wires to multiple banks.

The one drawback of tokenized fiat money is that it’s not as decentralized as a pure cryptocoin. Trust and transparency are very important for such products, and the people at Tether have not been good about either, leading the value of the token to at times fall below $1, and the whole project to be at the center of countless crpyto-conspiracy theories.

That’s why one of the biggest announcements to come out of the Consensus conference back in May was the creation of a new tokenized dollar product by Circle, the Boston-based crypto trading company originally backed by Goldman Sachs and now Bitmain, the biggest name in Bitcoin mining. Unlike Tether, Circle’s USD token will be domiciled in the United States, audited by a trusted third party and compliant with US money regulations.

Should Circle succeed in its implementation, the financial community, along with average consumers, will have access to a product that combines all the benefits of blockchain based transactions with none of the uncertainty or volatility of a pure cryptocoin. The next killer application to be moved unto the blockchain might very well be the fiat money some thought the technology would replace.

July 6, 2018

The Case Against Crypto Market Conspiracy Theories

I used to be a professional trader, and although I eventually switched careers on account of too much stress and too little to show for it, the experience taught me several important lessons. The biggest one was that other than the basic notions of supply and demand, we often have no idea why markets do what they do.

That concept is anathema to all of the analysis, pundits and academics who are paid to tell us what happened, but it’s the truth, because it has to be.

You’ve probably heard the saying that “trading is a zero-sum game,” meaning that for every winner there has to be a loser. But that’s an understatement, because the brokers, exchanges and tax collectors always get paid. So in reality, on any timeline short of hodl, trading is a negative sum game. The average trader, like the average casino patron, will lose, sort of like the markets own law of money thermodynamics. The preferred enforcement mechanism? Confusion.

One of the most distinguishing characteristics of crypto markets is the prevalence and popularity of conspiracy theories. Every major move is explained by a shadowy group enforcing their will on everyone else. Why did Bitcoin go to $20k? Because Tether. Why did it crash to $6k? Because futures. Why does a small coin go up? Pump and dump. Why does a large coin go down? Whales!

Today, I’m going to make the case against these theories, starting with the simple argument that since markets are inherently inexplicable, no explanation, however benign or nefarious, should be given too much credibility.

That point is not as controversial as it sounds. Most veteran Wall Street traders would probably tell you the same thing, and one of the most popular investing books of the past 20 years is dedicated to the subject. My old boss, who used to write a column for a leading financial newspaper, was once told by reporters at his paper that even though they wrote daily headlines that explained the market, they really had no idea.

Some of the conspiracy theories out there are backed by statistical analysis. I’m even more skeptical of those, as crunching numbers formed the core of my old trading strategy, and years of doing so led me to one important conclusion: if you have a big enough dataset, and do enough research, you could find stats to prove almost anything.

That statement is not all that controversial, either. It was often conveyed down the trading desk via a fable about my mentor, one of the founding fathers of stat-driven trading. Supposedly, he once had a junior analyst so talented that he could make a statistically significant argument to go both long and short on any given day. So every morning, the analyst would show up with two envelopes of research behind his back, and ask the head trader whether he was feeling bullish or bearish. Upon hearing the answer, the analyst would respond with “then you want this envelope.”

Crypto traders have always been prone to believing in conspiracy theories, but the tendency has been kicked into overdrive of late thanks to the publication of academic papers claiming that Tether was used to manipulate Bitcoin up and futures used to bring it down.

Both reports are demonstrably wrong.

I traded futures for a living, so anytime I hear someone claim anything about them, I check the stats, as all trades on regulated futures products have to be reported. The one thing that’s abundantly clear about Bitcoin futures is that the actual level of usage has been small, bordering on insignificant.

The open interest, or total number of bets, in the past six months has never gone far past a few thousand contracts, or literally a fraction of the number of Bitcoins that get traded around the world in a single day. It’s unlikely that someone could manipulate a gigantic market using a tiny one.

Tellingly, the people who perpetuate this theory also perpetuate the false belief that until the launch of the CME and CBOE futures, there was no way to bet against, or short, Bitcoin. The paper above states:

“Before December 2017, there was no market for bitcoin derivatives. This meant that it was extremely difficult, if not impossible, to bet on the decline in bitcoin price.”

Except that the Bitmex Perpetual Swap Contract has been around for years and has always let you short. It’s literally the world’s most liquid Bitcoin market, and anyone could have used it to bet against Bitcoin on the way up, with massive leverage to boot.

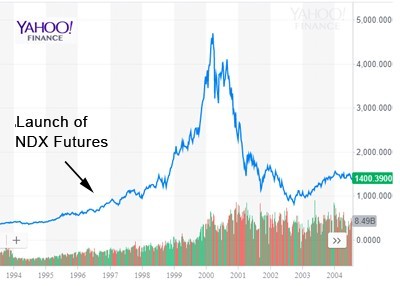

Curve fitting is a popular sport among those prone to being fooled by randomness, and the best way to win is by leaving out examples that disprove your thesis. So while the FRBSF paper sites other markets, like housing, that topped out with the introduction of new derivatives, it conveniently leaves out the case of the Nasdaq 100 stock index.

Futures on that market were introduced in April of 1996, shortly before the dot com bubble that took the index from 600 to almost 5000, a seven hundred percent gain that blew up lots of people shorting the futures along the way. And if that’s not convincing enough, consider futures on the 10 year US Treasury Note, which were introduced in 1982, right at the start of one of the greatest bull markets in fixed-income history.

So if our academic friends had wanted to, they could have just as easily argued that the introduction of futures makes a market go up. Why didn’t they? Probably because they assumed — correctly — that you’d rather see the other envelope.

No crypto conspiracy theory has been more popular than the ones regarding Tether, and they all seem to have hit critical mass after the publication of this research paper, filled with scientific-sounding claims such as:

“Less than 1% of hours with such heavy Tether transactions are associated with 50% of the meteoric rise in Bitcoin and 64% of other top cryptocurrencies”

As we used to joke in my quant trading chat room, if it sounds like science, it’s probably science fiction. I’ll leave the line by line takedown of their analysis to others, because I want to focus on the big picture questions of How and Why.

Tether is tiny, at least relative to the overall market, hovering around 1% of the total crypto market cap. On top of that, only a fraction of the tokens are claimed to have been used to manipulate the market. To believe that the people who control Tether and Bitfinex used fake tokens to drive the crypto rally is to believe that just a few million dollars worth of something was enough to explode the value of the space by $500 billion. That’s an unlikely bang for the (tokenized) buck.

Even if such manipulation was possible, nobody has ever given me a satisfactory explanation as to why. Crypto exchanges are an increasingly valuable business, so the one thing we know for sure about the people who own Bitfinex and Tether is that they already own one valuable asset. I think it’s also safe to assume that what they don’t own is a majority of all the cryptocoins in existence. To believe that these people tried to manipulate the entire market higher is to believe that someone would jeopardize their own valuable asset (not to mention going to jail) to pull off a feat that would mostly benefit others — including you, Novo and the Winklevoss twins.

Would you risk a billion dollars to help the competition?

None of this is to say that there isn’t plenty in the crypto space that’s shady. Tether leaves a lot to be desired in terms of transparency, and there have been plenty of fraudulent ICOs and penny coin pump and dumps. But none of that explains why crypto exploded in 2017 and crashed in 2018.

So what does? Only that demand was more than supply, and then supply was more than demand. Everything else is conjecture. Uncertainty is a necessary condition of the market law of thermodynamics.

The one thing we do know is that crypto markets have always been insanely volatile, as any brand new asset class with no established valuation metrics would have to be. It’s not Tether and futures, it’s just FOMO and FUD; Buy the rumor, sell the news.

But that explanation doesn’t make for attention grabbing headlines, give skeptics a chance to mock crypto or give regulators an excuse to crack down, so it doesn’t get much airplay. What does are meaty conspiracy theories that presuppose that unlike the rest of us dolts, the would-be manipulators always have perfect knowledge of cause and effect. The Tether buyers somehow knew that their actions would make the market go up, and the futures sellers must have known that their shorting would definitely force the market down.

And therein lies the greatest argument against crypto conspiracy theories. If the perpetrators understand the markets that well, they don’t need to manipulate them. They’d make just as much money trading them.

Omid Malekan is the author of The Story of the Blockchain, A Beginner’s Guide to the Technology That Nobody Understands .

May 22, 2018

Can Bitcoin Become a Flight to Quality Asset?

2018 might be the year we find out.

There’s an old saying on Wall Street that when times are good, you should focus on the return on your capital, but when times are bad, you should only care about the return of your capital. A flight to quality asset then is anything that tends to go up in times of turmoil because investors perceive it as a safe place to park their money.

Upon first glance, Bitcoin is a terrible candidate for such a role. It’s volatile, hard to understand, and difficult to access given how it exists outside of the traditional banking system.

So why would anyone consider it desirable during a crisis? Because it exists outside of the traditional banking system.

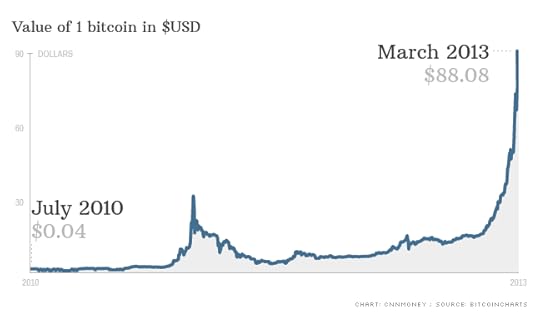

One of the first parabolic up-moves for the cryptocoin began with a banking crisis in Cypress. Back in 2013, while still reeling from the aftermath of the financial crisis, the tiny Mediterranean country found its banking system teetering, and reached out to the bigger European powers for help.

But instead of offering them a bailout, the EU came back with something more along the lines of a bail-in, as it demanded that Cypriot banks confiscate a portion of their customers deposits to shore up their balance sheets. To add insult to injury, they also imposed capital controls that prevented people from moving their money to a safer jurisdiction.

As you can see on the chart below, a decentralized form of money like Bitcoin, despite its drawbacks, can suddenly look very appealing when the centralized system starts to falter.

Crypto skeptics who tell us that digital money should not be worth anything often forget that fiat money like the Euro is also in of itself worthless. It’s only valuable when someone else is willing to trade a good or service for it. But you can’t get anything in exchange for money that the government is taking or locking up, which is why the Cypriot crisis brought a lot of attention to the then relatively unknown Bitcoin.

Government officials don’t like cryptocoins because they transfer the sovereignty of money from their control to a decentralized consensus mechanism, a transfer that they view as a downgrade in the quality of money. If our existing system of money and banking was always stable, they would have a point.

But every time there is a crisis, it reminds the public that the folks in charge are not as smart as they think they are. When those same leaders respond to the crisis with draconian capital controls (or selective bailouts for their once and future employers on Wall Street) they remind the public that they aren’t as fair as they think they are, either. Bitcoin might be volatile and hard to understand, but it’s always fair, because math does not discriminate, nor does it change the rules when people start to panic.

So why bring this issue up now? Because there is financial trouble brewing in certain corners of the global financial system, and if things continue to deteriorate, this year might serve as an important test of the crypto economy.

Iran and Venezuela are in the midst of the kinds of hyperinflationary currency death spirals that bring societies to their knees. In Argentina, the peso has fallen to an all-time low against the dollar as inflation and interest rates spike. Turkey is having problems of its own, and China continues to do everything it can to prevent its citizens from liberating their own money.

Some of this weakness was to be expected, because the Federal Reserve is now removing the liquidity it has provided for the past decade. But there’s a bigger issue in play, as the perennial economic mismanagement of developing nations is now rubbing up against the increasing political instability (Brexit, Trump, Catalonia, Five Star) of developed ones.

In the old days, the two best candidates for flight to quality assets were gold and the Dollar. But the former is hard to get a hold of and even harder to store, and the latter is no panacea either. When the Argentinian government last devalued its currency back in 2001, it first forced all local banks to convert the dollar-denominated accounts of its citizens to the Peso. Even the citizens that were smart enough not to trust the local currency had their savings destroyed, learning the valuable lesson that dollars in the bank is not the same as dollars under the mattress.

One of the most important takeaways from past financial crisis is that when the stuff hits the fan, banks are nothing more than a policy tool for the government. So can a cryptocoin like Bitcoin be considered a flight to quality asset for certain countries? Given everything we’ve learned in the past 20 years, a better question to ask might be how could it not.

Omid Malekan is the author of the newly published The Story of the Blockchain: A Beginner’s Guide to the Technology That Nobody Understands. You can purchase it on Amazon .