Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 26

April 9, 2021

The Battle of Britain through German Eyes -- The Air Offensive Begins in Earnest - "Eagle Day"

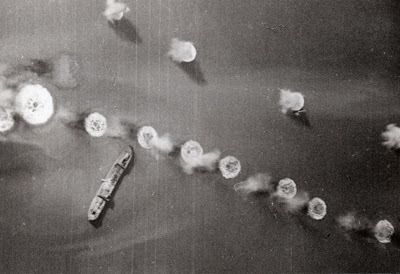

On the morning of 13 August 1940, the German Luftwaffe opened its main offensive against British air defenses. The Nazis designated this “Eagle Day.” The objective of this phase of the Battle was to destroy the ability of the Royal Air Force to defend British air space. The targets of the offensive were first and foremost the RAF airfields themselves, but also the aircraft industry replacing RAF losses and the radar installations vital to command and control of Britain’s fighter forces.

German Bombers - Courtesy of Chris Goss

German Bombers - Courtesy of Chris GossThe Luftwaffe opened its main offensive against British air defenses with high morale. According to their calculations, during the Kanalkampf they had achieved a “kill ratio” (number of enemy aircraft shot down per friendly aircraft lost) of 5:1. That is, they believed that they had destroyed five RAF aircraft for every Luftwaffe loss. German intelligence, meanwhile, underestimated British aircraft production by 50% — that is they believed the British aircraft manufacturers were delivering only 250 fighters per month when, in fact, under Lord Beaverbrook’s management British aircraft factories were producing 500 Hurricanes and Spitfires every month.

On the eve of Eagle Day, to pave the way for the main assault, the Luftwaffe targeted Britain’s “eyes” — the radar installations along the coast. In the early hours of the morning, the Luftwaffe’s Test Flying Wing (Erprobungsgruppe) 210 attacked the radar stations at Dover, Pevensey and Rye, putting all three out of action. Fighter Command was blind from East Kent to West Sussex. Notably, the Test Flying Wing consisted of Me110s and Me109s converted into fighter bombers. They came in fast and low — and all returned without encountering a single British fighter.

Later that same morning, a force of bombers larger than anything seen up to this point made a determined attack on both Portsmouth and the Ventor radar station on the Isle of Wight. Last but not least, the Luftwaffe hammered RAF forward airfields at Manston, Lympne and Hawkinge, all three of which temporarily rendered unusable.

As the day ended, the Luftwaffe believed they had shut down four radar stations, rendered three airfields inoperable and destroyed (they claimed) forty-six Spitfires and twenty-three Hurricanes. In fact, by the end of the day, the airfields were all again operational. Of the radar stations, the three mainland radar stations were back on the air; only Ventor would remain inoperable for three more days. As for the RAF, “only” twenty aircraft had been destroyed in the air, although some aircraft were lost on the ground in the attacks on the airfields.

“Eagle Day,” August 13, dawned with uncertain weather and Goering ordered the great assault on Great Britain postponed until the afternoon. However, the postponement orders only reached some of the units designated to participate, resulting in these staying on the ground or turning back, while others proceeded — with inadequate fighter escort. The low cloud that had induced Goering to want to postpone the operation provided some protection, but eventually the bombers were found and five bombers were shot down for the loss of a single Spitfire.

Bizarrely, however, all the attacks carried out were against comparatively unimportant targets. The bombers went for Eastchurch, which was a Coastal Command station, and raided the airfields at Farnborough and Odiham, neither of which were used by Fighter Command. Me110s also undertook a free sweep that resulted in the loss of six of their number but claimed nine Spitfires. In fact, they had tangled with the Hurricanes of 601 Squadron, which suffered only one aircraft lost and two damaged in the engagement. (The claims of Spitfires shot down was “Spitfire snobbery,” i.e. the Luftwaffe’s perpetual refusal to recognize how deadly the Hurricane was and for pilots to dogmatically insist were dog-fighting with “Spitfires” even when they were facing Hurricanes.)

At 14:00 the units that had received the postponement orders took off at last and proceeded in large numbers to again assault airfields the Luftwaffe apparently considered vital: Boscombe Down, Worthy Down, Andover, Warmwell, Yeovil, Rochester, and Detling. Readers familiar with the Battle of Britain will note that none of these airfields were vital Fighter Command Sector Airfields. From the latter, the RAF dispatched fighters to intercept the intruders, bringing down 47 aircraft altogether.

At the end of the day, the Luftwaffe leadership was acutely aware that the mix-up about timing had hurt them and cost them lives and aircraft, but they consoled themselves with the “fact” — unfortunately largely self-fabricated — that they had destroyed 84 RAF fighters. The correct figure for RAF losses were 13 aircraft lost in the air and one on the ground. RAF pilot losses amounted to just three. The RAF had handily won on Eagle Day — the Germans just didn’t know it yet.

August 14 was comparatively quiet as the Luftwaffe prepared for their next “big” day. This was to be a broad attack along the entire south coast of England and — exceptionally — including Luftwaffe units based in Norway and Denmark against targets in the North of England. The Luftwaffe assumed that the RAF had only been able to put up such a spirited defense in the southeast in recent days because it had denuding the rest of the country of fighters. The Luftwaffe remained confident that the Me110s, which had the range to carry out missions over the distances involved, would now prove their worth.

The targets were again predominantly airfields, although a factory producing Stirling bombers was also hit. The factory was so badly damaged that production was halted for three whole months, but the impact on the Battle of Britain was nil. Other attacks were more significant. Martlesham Heath was put out of action for 48 hours and bombs intended for Hawkinge severed the power cables to the radar stations at Rye, Foreness and Dover, again blinding Fighter Command in this vital sector for a whole day. Also, toward the end of the day, raids were sent against Kenley and Biggin Hill — the first time Sector Airfields essential to Fighter Command’s ability to defend the country were targeted.

The results for the Luftwaffe were shockingly disappointing — and this time they knew it. The northern raids had been intercepted early, forcing many bombers to drop their loads into the sea, while the Me110 again proved completely incapable of providing an effective protection for the bombers. The raids on the south had provoked a savage response and many of the targets had been missed. Critically, instead of Biggin Hill, the Luftwaffe had bombed West Malling, a satellite airfield still under construction, and instead of Kenley they had hit the satellite airfield at Croydon. Altogether the Luftwaffe had flown 2,000 sorties and lost 75 aircraft, including some key senior officers.

While the Luftwaffe's loss rate of 3.75% was far below what RAF Bomber Command and the U.S. Eighth Air Force would endure at the height of the Allied bombing offensive, it was sobering to an air force that until this date had believed it was easily winning the air war against Britain. August 15 went down in Luftwaffe history as “Black Thursday.”

Goering drew some lessons from the disaster. The Stukas, he concluded, needed to be defended better — by three full Gruppe of fighters. He also ordered fresh fighters to meet the waves of bombers coming out, recognizing that the escort fighters would be nearly out of fuel and unable to engage on the return leg. Goering also stipulated that the focus of all future attacks much remain the RAF and the aircraft industry, but he made a serious error. Believing that successful attacks on airfields rendered them inoperable for at least 24 hours or more, he ordered that the same airfields should not be targeted in quick succession. In fact, even airfields that were badly hit were usually operational again within hours. By stopping attacks in quick succession, Goering gave the RAF fighter stations a breather. Overall, however, the pressure was to be maintained.

On August 16, the important Sector Airfield of Tangmere was badly hit and so was the Ventnor radar station. The former was only temporarily inoperable, but Ventnor was knocked off the air for seven days. Other targets that day were the Portsmouth docks, Manston, and the non-Fighter Command airfields at Lee-on-Solent and Brize Norton. At Tangmere, the Stukas were attacked by Tangmere based squadrons with such viciousness and effect that 70% of the Stuka unit engaged was wiped out. Nevertheless, based on the intelligence reports received and (false) assumptions about aircraft production, the Luftwaffe General Staff concluded that the RAF had at most 300 operable fighter aircraft left. In fact, there were 855 serviceable aircraft with front line squadrons alone, and another 363 fighter aircraft available at training units and maintenance units.

But ignorance is bliss and the Luftwaffe prepared for another “big” day: August 18. The Luftwaffe saw no need for an early start, and it was not until mid-day that the Luftwaffe assembled their air armadas. Large numbers of He 111s, Do 17s and Ju 88s were detailed to attack Kenley and Biggin Hill, protected by no less than 410 Me 109s and 73 Me 110s. The Luftwaffe’s plans also called for a three-stage attack composed of 1) an initial dive bombing attack to destroy ground infrastructure, followed by 2) a high-level attack to shoot down RAF fighters that came up to defend their airfield, and finally 3) a low-level raid to finish the station off with strafing as well as bombing.

Unfortunately, even the best-laid plans can go wrong. Cloud resulted in some confusion and the low-level raid without fighter escort reached the target first, only to encounter the full fury of the defenders. When the other bombing contingents put in their appearance, however, the RAF was soon stretched and fighting so hard that several fighters were lost to friendly ground fire. Furthermore, some of the German fighter commanders had figured out that Manston was used for refueling RAF fighters. They decided to strafe the field while going in to take over the escort of returning bombers, catching four RAF fighters on the ground.

Meanwhile, farther west, Luftflotte 3 sent Stukas against the non-Fighter Command airfields of Gosport, Ford and Thorney Island and the radar station at Poling. Fighter Command was able to muster six squadrons to oppose these raids and the Stukas were again slaughtered. Seventeen were destroyed and six damaged, while eight of the escorting Me 109s were also shot down. The RAF on the other hand had lost five aircraft but only two pilots. Although the Luftwaffe could not know that the RAF’s losses, they did know that one of their Stuka groups had sustained 50% casualties — and this after losses of 70% in the raid on Tangmere two days earlier. Such losses were not sustainable regardless of the successes.

Meanwhile, the last raid of the day targeting Hornchurch and North Weald took off at 17:00. The RAF went up in force to meet them and was understandably gratified when the bombers turned back. The reason for the retreat, however, was cloud cover over the targets rather than fear of the RAF. Only four bombers were lost, but ten of the Luftwaffe’s escorting fighters were shot down for a loss of nine RAF fighters.

Altogether on August 18, the Luftwaffe lost 69 aircraft destroyed and 31 damaged in order to knock out 34 RAF fighters and damage 39. Furthermore, since the opening of the offensive, the Luftwaffe had lost roughly 300 aircraft, thirty percent more than in the entire previous month. Yet Goering’s response to the situation was essentially “more of the same.”

To be sure he promoted his top-scoring aces to “Kommodores,” reorganized the units, changing who was responsible for what, and also moved them around a bit geographically, but Goering made few changes in tactics. RAF Fighter Command remained the principal target, with the aircraft industry, other RAF bases and the Royal Navy as secondary targets to be attacked when circumstances were “right.” He pulled back his Stukas and allowed his fighters a little more leeway for free hunting rather than insisting on specific escort ratios, but he also made it abundantly clear that he wanted his bombers protected and the escorts would be blamed for unacceptable losses. A spell of bad weather then set in that gave both sides a breather before the battle continued again. Same song, second verse, doesn’t get better ….

“Where Eagles Never Flew” shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The attacks on the RAF airfields and radar naturally figure prominently. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagl...

Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

April 1, 2021

The Battle of Britain through German Eyes - The Battle for the Channel (Kanalkampf)

From the German perspective, the main objective of the air offensive against England in the summer of 1940 was to force the British to the negotiating table. While the Navy and Army produced dilettantish plans that would have stood little chance of success in the short-term, the Luftwaffe was tasked with putting the fear of God (or Hitler as the case may be) into the hearts of the stubborn British. The Luftwaffe leadership was delighted with the opportunity to show what they could do, Herman Goering, appears to have sincerely believed that the task would be complete within weeks. Yet, in line with the goal of bringing the British to sue for peace, the Luftwaffe did not at once launch an all-out offensive. The Luftwaffe followed a strategy that can be divided into clear phases, the first of which was the “Kanalkampf” or “Channel Battle.”

Photo Courtesy of Chris Goss

In preparation for a proper air offensive, on 30 June 1940 Herman Goering ordered the Luftwaffe to start pin-prick attacks on Great Britain. The primary objective of these attacks, which were explicitly kept at a small scale, was to conduct reconnaissance and test the air defenses of the opponent. However, the secondary objective was to close the English Channel to British shipping. The reasoning was: if the British government proved obstinate and refused to negotiate, then the Channel would have to be cleared of British shipping (read warships) to facilitate the German seaborne invasion of the British Isles.

In accordance with these orders, the Luftwaffe initiated operations on a small scale. Initially, the Luftwaffe sought to draw the RAF up and into combat by conducting fighter sweeps over British airspace. The Luftwaffe was confident that if the RAF engaged the German fighters, the British fighters would be destroyed in the ensuing dogfights. Unfortunately for the Luftwaffe, AVM Park did not take the bait and to the extent possible avoided launching his squadrons when the Luftwaffe sent only fighters across the Channel.

So, the Luftwaffe was forced to lure the RAF off the ground by other means. This took the form of attacks on “targets of opportunity” with small numbers of bombers. These targets included docks and ships, railway stations and airfields, oil installations and the like. While all were legitimate military targets, the scale of the attacks was too small to destroy them. These were “nuisance raids” — and rarely provoked more response from the RAF than the fighter sweeps.

On July 10, Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft spotted a juice “target of opportunity” in the form of a large convoy making for the Straits of Dover and ordered an assault on it. The RAF sent a flight of Spitfires to defend the convoy — a moderate and measured response. Yet both sides called in reinforcements and the largest single dogfight of the war so far ensued — causing many historians to date the start of the Battle of Britain from this day.

Both sides claimed victory. The RAF had successfully broken up the bomber formations and prevented their effectiveness; only one ship was lost. In addition, they had destroyed six Luftwaffe aircraft (three bombers and three of the escorting Me110s) for the loss of only one aircraft and pilot, although four additional Hurricanes had sustained damage. Significantly, however, the Luftwaffe was convinced they had just attained a stunning victory. They believed they had shot down thirty RAF fighters! The German Army High Command (OKW) was told that the RAF would be “neutralized” in between two to four weeks.

In the following days, fate favored first one and then the other side, and both air forces learned valuable lessons. The Germans learned that the British would shoot down their air ambulances mercilessly, despite the fact that they were unarmed and marked by the Red Cross — something the Germans considered barbaric right to the end of the war. The Germans also gradually came to recognize that the Me 110 was not a match for the British Hurricanes and Spitfires. The British, however, learned that their own two-seater fighter was a disaster. On July 19, the Luftwaffe annihilated the RAF’s only Defiant squadron in just 30 minutes.

Perhaps it was this victory that encouraged Goering to make a dramatic appeal to the British public in a speech before the Reichstag that same evening. Goering argued that the British were already defeated and there was no need to senselessly prolong the destruction and casualties. Recognizing that Churchill was not receptive to peace overtures, Goering’s speech was aimed not at the British government per se, but rather at presumably reasonable and peace-loving elements inside Britain, who were thereby encouraged to bring down Churchill’s government. Goering is said to have been astonished that his words did not fall on fertile ground. The BBC sent a rejection within an hour, while the official rejection was broadcast by Lord Halifax — the leader of the British peace faction — two days later.

In consequence

, on July 21, Goering met with his senior commanders to discuss tactics for an upcoming offensive, which now appeared inevitable. Except for adding British warships to the favored targets, the tactics remained largely unchanged. Goering still favored using small numbers of bombers to lure up the RAF where large and free-roving swarms of Luftwaffe fighter could shoot them down, but he moved top-scoring “aces” into senior command positions, apparently on the assumption that they would produce better results.Whatever the reason, the results were satisfying. On July 25, a westbound convoy was all but wiped out, only two merchantmen remaining afloat at the end of the day, and two Royal Navy destroyers sent to their assistance were so badly damaged that they were withdrawn from the fight. The Admiralty concluded that the advantages of sending shipping through the Straits of Dover did not justify the risks and cancelled all merchant shipping in the confined waters of the Channel by daylight starting July 26. Two days later, because RAF reconnaissance showed that long-range guns were being installed at Calais the Admiralty went one step farther and abandoned Dover as a base for the Royal Navy. Thus by July 29, the English Channel was effectively closed to all British shipping during the hours of daylight. The Germans had every reason to think they were winning the Kanalkampf.

On 1 August 1940, Hitler issued a new directive ordering the Luftwaffe to start the destruction of the Royal Air Force. The warm-up phase of probing and luring was over. It was time to knock-out the opponent — as soon as the weather permitted. What this meant was the days of the pin-prick nuisance raids and free-roaming fighter sweeps were over. In their place large scale attacks involving much larger numbers of bombers were to take place, and the German fighters were to provide much closer protection for the bombers. The date of the offensive was set for August 10 and then postponed due to weather conditions until the 13th.

Meanwhile, however, the Kanalkampf continued. On 7 August, a British attempt to slip a convoy through the Straits of Dover under cover of darkness resulted in a massacre of British merchantmen. Of 20 ships, only four came through unscathed, while seven were sunk outright, six rendered temporarily unseaworthy, and the remainder damaged. The RAF had, furthermore, lost thirteen fighters while another five were shot up while bringing down ten Stukas, four Me 110s and two Me 109s. The Germans claimed 20 British fighters, reinforcing their sense of superiority and victory.

August 11 saw three separate air battles, two over convoys off the Essex coast and the Thames Estuary and a third over the naval base of Portland on the Dorset coast. The later was a taste of things to come with 165 German aircraft deployed on the raid, the largest raid against British targets up to that time. British and German aircraft losses were almost identical. Nineteen Luftwaffe aircraft (five bombers, eight Me 109s and six Me 110s) were shot down and an additional six sustained damage. The RAF lost sixteen fighters and an additional seven aircraft were damaged.

However, the Luftwaffe claimed fifty-seven kills, including aircraft types never deployed by the RAF at all. Only the loss of three senior officers, two Gruppenkommandeure and one Staffelkapitaen among the bomber crews dampened the Luftwaffe’s sense of winning as they prepared for what they expected to be “the final assault” on the RAF.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The "Kanalkampf" naturally figures prominently. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagl...

Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

March 26, 2021

The Battle of Britain Through German Eyes -- An Introduction

Britain won the Battle of Britain and it is well-known that the victors write history. As a result, most accounts of the Battle of Britain are written from the British perspective. Yet looking at German expectations, strategy, and responses provides insight and shading which are lost when looking at the events of the Summer of 1940 only through British eyes. In a five-part series, I propose to look at the Battle of Britain from the German point-of-view starting today with an introduction. In coming weeks, I will consider from the German perspective each of the three main phases into which the Battle is conventionally divided: 1) the Channel Battle, 2) Attacks on British Air Defences (Phases I and II) and 3) the Raids on London.

On June 22, 1940 France capitulated to Nazi Germany. Hitler had revenged the humiliation of the First World War — forcing the French military leadership to sign the armistice in the same railway car used for Germany’s surrender in 1918. In less than ten months Hitler had defeated Poland, Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium and France militarily. A non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union secured his rear in the east, and his ally Italy dominated Southern Europe and the Mediterranean. Hitler was master of Europe.

Of course, Britain was technically still at war with Germany, but it had been defeated on the battlefield. Its army had managed to slip across the Channel in a surprise (but highly amateurish) operation involving massive numbers of small boats manned by civilians (hardly a show of military might!) and it had left all its heavy equipment behind. The Royal Navy, while still formidable, had been badly mauled defending the vessels engaged in evacuating British forces from Dunkirk. Six destroyers had been sunk and nineteen damaged, while 200 lesser vessels had also been lost. What remained of the Royal Navy was needed — desperately — to defend the “Atlantic Lifeline” from German U-Boats and air attacks in the confined waters around Britain’s coast. In short, Britain was in no position to undertake an offensive against Germany and many doubted if it could successfully ward off a German invasion. Britain had not been so vulnerable since Napoleon had dominated Europe more than a hundred years earlier.

However, in June 1940 the Germans had no plans for an invasion of Great Britain. Hitler had long harbored admiration for Britain. In Mein Kampf Britain and the British Empire was singled out for rare praise, and Hitler comparatively accurately described British foreign policy as one of maintaining a balance of power on the Continent which was not inherently anti-German. He criticized the German Imperial government for building a High Seas Fleet and seeking Colonies because they needlessly provoked British ire. Hitler not only saw the British as fellow Aryans, members of the "Master Race," he saw the British Empire as a natural ally of Nazi Germany. His ideological goals were the destruction of "World Jewry" and the defeat of Communism, while his military ambitions were focused on the destruction of "subjugation of the Soviet Union.

Because the British had acquiesced in Hitler’s annexation of Austria and the Sudetenland as well as his invasion of Czechoslovakia, Hitler had not expected a British declaration of war following his invasion of Poland. He was allegedly angry, but not unduly upset. The “Phony War” between September 1939 and April 1940 reinforced Hitler's assumptions about British reluctance to fight him. The short work made of the British Expeditionary Force in May-June 1940 served to convince him that Britain was not a threat to him or his continental ambitions. It has even been suggested that Hitler stopped his panzers from crushing the BEF at Dunkirk because he did not want to humiliate Britain. Certainly, he assumed that now that the French had been knocked out of the war, the British would “come to their senses.” Allegedly, Hitler told his senior military leaders: “The British have lost the war, they just don’t know it yet. We need to give them time, and they will come around.”

Hitler was not alone in his expectations. It was widely assumed in Washington, Moscow, Tokyo and elsewhere that Britain would sue for peace. Indeed, members of Parliament, senior British diplomats, even members of Churchill’s war cabinet including his Foreign Minister Lord Halifax favored a “peaceful resolution” of the differences between Britain and Germany. In late-June 1940, Churchill was politically more isolated than is commonly recognized, and the attitude of the British public had not yet to be tested.

When the expected peace overtures did not materialize, however, the Oberkommando der Wehrmach (OKW) drafted a memorandum on a possible invasion of Great Britain. This was not a detailed invasion plan. It bore no resemblance whatsoever to the careful preparations that would go into the Allied landings in Normandie four years later. Nevertheless, it formed the basis of a “Fuehrer Directive,” ordering preparations for the invasion of England, an operation code-named “Sea Lion.” While the Army and Navy were tasked with developing more detailed plans (even as army divisions were disbanded or put on a peacetime footing), the Luftwaffe was directed to take action to pave the way for an invasion by establishing air superiority over the South of England.

In other words, the Luftwaffe offensive of 1940 was never intended as strategic bombing campaign to destroy British industrial capacity. Nor was it a terror bombing campaign intended to destroy British morale. Rather, it was a tactical offensive in which the Luftwaffe was expected to play its now traditional role of supporting the other branches of the Wehrmacht.

Starting in mid-July 1940, the German Navy halfheartedly came up with plans to land on a narrow front and collected a variety of largely unsuitable barges in the French channel ports. For its part, the German Army argued for landing troops on a broad front and did even less to mobilize resources. Hitler did not to resolve the differences in strategic approach and otherwise demonstrated only lukewarm interest in the campaign — beyond saying everything should be ready by Sept. 15.

What Hitler, the German Navy and the German Army leadership all hoped was that the mere show of force, “sabre rattling” in the form of an air offensive, would frighten Britain to the negotiating table. Hitler’s directive explicitly stated: “I have decided to prepare a landing operation against England, and if necessary, to carry it out.” (Italics added.)

The key to making sure it wasn’t “necessary” was an air offensive intended to convince the British government to sue for peace. The Luftwaffe was expected to achieve this objective within a few weeks.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. In addition, it highlights the elements in British society favored a peace with Hitler. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagl...

Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

March 19, 2021

"Lack of Moral Fibre" (LMF) - The RAF and Aircrew Morale in WWII

The term “Lack of Moral Fibre” was introduced into RAF vocabulary in April 1940 and was ‘designed to stigmatize aircrew who refused to fly without a medical reason.’ [1] While it is now most commonly associated with ‘shell-shocked’ bomber crews, in fact aircrew from all commands could be and were categorized as LMF in the course of the war. Humiliating as the concept was, the myths about the treatment of LMF were more terrifying than the facts .

The RAF entered the war confident that its volunteer aircrew, all viewed as the finest human material available, would not suffer from any crisis in morale. Yet already by January 1940, attrition rates of over 50% in Bomber Command, triggered a crisis in confidence among commanders and crews. At the same time, Coastal Command morale was undermined by unreliable engines and unarmed aircraft that proved extremely vulnerable to Luftwaffe attack.

On March 21, 1940 the Air Member for Personnel met with senior RAF commanders to develop a procedure for dealing with flying personnel who refused to ‘face operational risks.’ The concern of these senior officers was that the refusal to fly would become more widespread, debilitating the RAF. The RAF’s dilemma was that flying was ‘voluntary,’ hence the refusal to fly was not technically a breach of the military code.

The RAF needed an alternative means of punishing and deterring refusals to fly on the part of trained aircrew. Furthermore, because of the on-going crisis, the procedures for dealing with the problem were required immediately. There was no time for lengthy study into the causes or best practices for treatment. Over time the polices on LMF were modified significantly and increasingly discredited. Yet it is telling that at the height of the Battle of Britain, AVM Sir Keith Park strongly advocated the policy, emphasizing that aircrew deemed LMF should ‘be removed immediately from the precincts of the squadron or station.’

Furthermore, while nowadays LMF is most commonly associated with bomber crews, the statistics show a that only one third of LMF cases came from Bomber Command. Surprisingly, fully a third came from Training Command, while both Coastal and Fighter Commands also had their share of LMF cases. Fighter Ace Air Commodore Al Deere describes in detail a case of a pilot from No 54 Squadron who avoided combat and was later ejected from the squadron for being “yellow.”Fighter Ace Wing Commander Bob Doe records another incident towards the end of the Battle of Battle of Britain in which a Squadron Leader conspicuously avoided combat, but because the Squadron Leader was from a different squadron, no action was taken.

For the men who continued flying operations, the fate of those ‘expeditiously’ posted away from a squadron for LMF was largely shrouded in mystery. Legends about LMF abound. During the war itself, it was widely believed that aircrew found LMF were humiliated, demoted, court-martialed, and dishonorably discharged. There were rumors of former aircrew being transferred to the infantry, sent to work in the mines, and forced to do demeaning tasks. Aircrew expected to have their records and discharge papers stamped “LMF” or “W” (for Waverer) with implications for their post-war employment opportunities.

Long before the war was over, however, the very concept of LMF was harshly criticized and increasingly discredited. In the post-war era, popular perceptions conflated LMF with “shell shock” in the First World War and with the more modern concept/diagnosis of Post Traumatic Shock Disorder/Syndrome PTSD/S. In literature — from Len Deighton’s Bomber to Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 — aircrew were increasingly depicted as victims of a cruel war machine making excessive and senseless demands upon the helpless airmen. Doubts about the overall efficacy of strategic bombing, horror stories depicting the effects of terror bombing on civilians, and general pacifism in the post-war era have all contributed to these cliches.

In reality, LMF was a more complex and nuanced issue. First, although there are documented instances of aircrew being humiliated in a parade during which flying and rank badges were stripped off, such public ceremonies were extremely rare. The vast majority of references to such public spectacles are second hand; that is, the witness heard about such procedures at a differentstation or squadron. Historical analysis of the records, on the other hand, show almost no evidence of widespread humiliation. Furthermore, over the course of the war, less than one percent of aircrew were posted LMF, and of these the vast majority were partially or completely rehabilitated. Only a tiny fraction were actually designated LMF or the equivalent. (The term used for describing aircrew deemed cowardly varied over time, including the terms “waverer” and “lack of confidence.”) Furthermore, the process for determining whether aircrew were LMF or not was far more humane than the myths of immediate and public humiliation suggest.

While the decision to remove a member of aircrew from a unit was an executive decision, applied when member of aircrew had “lost the confidence of his commanding officer,” the subsequent treatment was largely medical/psychiatric. Thus, while a Squadron Leader or Station Commander was authorized — and expected! — to remove any officer or airman who endangered the lives or undermined the morale of others by his attitude or behavior, a man found LMF at squadron level was not automatically treated as such by the RAF medical establishment.

On the contrary, RAF medical personnel were at pains to point out that LMF was not a medical diagnosis at all! It was a term invented by senior RAF commanders in order to deal with a phenomenon they observed — and feared. In consequence, once a man had been posted away from his active unit, he found himself inside the medical establishment that employed Not Yet Diagnosed Nervous (NYDN) centers to examine and to a lesser extent treat individuals who had “lost the confidence of their commanding officers.”

The medical and psychiatric officers at the NYDN centers (of which there were no less than 12) were at pains to understand the causes of any breakdown. They did not assume the men sent to them were inherently malingerers or cowards. On the contrary, as a result of their work they made a major contribution to understanding — and helping the RAF leadership to understand — the causes for a beak-down in morale. These included not only inadequate periods of rest, but irresponsible leadership, lack of confidence in aircraft, and issues of group cohesion and integration. As a result of their interviews with air crew that had been posted LMF, for example, the medical professionals were able to convince Bombing Command to reduce the number of missions per tour and to exempt aircrew on second tours from the LMF procedures altogether.

Meanwhile, more than 30% of the aircrew referred to NYDNs returned to full operational flying (35% in 1942 and 32% in 1943-1945), another 5-7% returned to limited flying duties, and between 55% and 60% were assigned to ground duties. Less than 2% were completely discharged.

In addition, there is considerable circumstantial evidence that at the unit level, pains were taken to avoid the stigma of “LMF.” No one understood the stresses of combat better than those who were subjected to them. It was the comrades and commanders, who were themselves flying operationally, who recognized both the symptoms and understood the consequences of flying stress. These men largely sympathized with those who were seen to have done their part. Certainly, men on a second tour of operations were treated substantially differently — at both operational units and at NYDNs — than men still in training or at the start of their first tour.

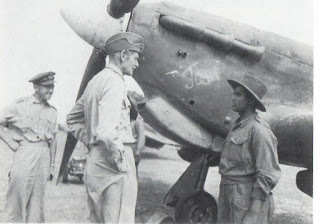

Fighter Ace Air Commodore Al Deere, DSO, OBE, DFC and Bar posed the dilemma as follows: “The question ‘when does a man lack the moral courage for battle?’ poses a tricky problem and one that has never been satisfactorily solved. There are so many intangibles; if he funks once, will he next time? How many men in similar circumstances would react in exactly the same way? And so on. There can be no definite yardstick, each case must be judged on its merits as each set of circumstances will differ.” (Photo below courtesy of Chris Goss)

While conditions varied over time, from station to station, and from commander to commander, on the whole RAF flying personnel did not seek to punish or humiliate a comrade who in the past had pulled his weight. Instead, informal means of dealing with cases of men who “got the twitch” — other than posting them LFM — were practiced. Precisely because such practices were “informal” they are almost impossible to quantify, yet the specific cases documented are almost certainly only the tip of the iceberg.

This is not to say that LMF policies did not have a powerful impact on RAF culture. The fact that so many aircrew knew about LMF and had heard rumors of humiliating practices for dealing with LMF demonstrates that the possibility of being designated LMF was an ominous reality to aircrews. Because of the draconian punishment expected based on the myths surrounding LMF, the threat of being designated LMF acted as a deterrent to willful or casual malingering. Tragically, the threat of humiliation may also have pushed some men to keep flying when they had already passed their breaking point, leading to errors, accidents, and loss of life.

Deere noted: “In my first tour [during the height of the Battle of Britain], despite the many narrow escapes I was always confident that I could come through alright. In contrast, throughout [a later tour], although it was far less hectic, there was always uppermost in my mind the thought that I would be killed….I don’t think I was any more frightened than previously, and it can only be that I had returned to operations too soon after so many nerve-racking experiences…. The result was a lack of confidence, not so much in my ability to meet the enemy on equal terms, but in myself (or my luck).”He admitted that by the time he was relieved of his command and sent on a publicity tour to the United States he was, in fact, overdue for another rest.

During the Second World War, psychiatric professionals increasingly came to recognize that “courage was akin to a bank account. Each action reduced a man’s reserves and because rest periods never fully replenished all that was spent, eventually all would run into deficit. To punish or shame an individual who had exhausted his courage over an extended period of combat was increasingly regarded as unethical and detrimental to the general military culture.”

Yet we should not forget that behind the notion of LMF was the deeply embedded belief that courage was the ultimate manly virtue and that a man who lacked courage was inferior to the man who had it. RAF aircrew were all volunteers. They were viewed and treated as an elite. Membership in any elite is always dependent on the fulfilment of certain criteria. Since the age of the Iliad courage has been — and remains — the most fundamental characteristic expected of military elites around the world. And it probably always will be.

A case of LMF is highlighted in and contributes pivotally to the plot of “Where Eagles Never Flew.” You can see a video teaser of "Eagles" at: Where Eagles Never Flew Video

Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

[1] Edgar Jones, “LMF: The Use of Psychiatric Stigma in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War,” The Journal of Military history 70 (April 2006). 439

[i]Jones, 446.

Deere, Alan C. Nine Lives. Crecy Publishing. 1959. 111-119.

Doe, Bob. Fighter Pilot. CCB Aviation Books, 2004. 44.

Deere, 112-113.

Deere, 232.

Jones, 456.

March 12, 2021

AVM Sir Keith Park -- The Man who could have lost the Battle of Britain

While Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding forged the instruments for fighting the Battle of Britain, it was AVM Sir Keith Park who used the tools Dowding had given him to obtain victory. Park alone could not and did not win the Battle. Without the courage of the pilots and the dedication of the ground crews, the Battle of Britain would still have been lost. But all the courage and dedication in the world would not have been enough for victory, if Park had not used his resources so brilliantly.

Keith Park was born in a small town in New Zealand in 1892, the son of Scottish immigrants. He grew up in New Zealand and started his adult life by joining the Union Steam Ship Company as a cadet purser. Already an enthusiastic hobby sailor, he seemed destined for a career at sea. WWI changed his fate.

In December 1914, Park volunteered for the New Zealand army. He participated in the Gallipoli campaign as a corporal in the artillery. He was commissioned in July 2015 and on September 1 transferred to the British Army. As a second lieutenant in the horse artillery, he took part in the Battle of the Somme. In late October 1916, he was severely wounded by shell-fire and evacuated to England. After a short spell instructing at the Artillery Depot, his transfer to the Royal Flying Corps, which he had been seeking for months, was granted and his flying career began. After learning to fly, he joined 48 Squadron in France in July 1917. By the end of the war, he was credited with twenty aerial victories and had been promoted to Major and appointed commanding officer of No 48 Squadron.

After the war, Park sought positions in New Zealand's fledgling aviation industry, but opportunities were few and competition stiff, so he remained in the UK and the RAF. He was one of the first men selected to attend the world's first air force staff college. From 1923 to 1925, he served in Egypt, but in mid-1925 he was asked to join the staff of the newly create Air Defense of Great Britain (ADGB). The latter was the first attempt by the RAF to formulate doctrine for the air defence of the realm, coordinating the efforts of anti-aircraft, observer corps, searchlights and aircraft as well developing means of communication suitable to escalating speed of contemporary aircraft. The work of the ADGB staff laid the foundations on which Dowding later built Fighter Command.

In November 1927, Park was allowed to leave this staff job for what many RAF officers consider the best job in the service: command of a squadron. Park was "given" No 111 (Fighter) Squadron stationed at Duxford and later Hornchurch. However, the interlude was typically short, and starting in March 1929, Park was back into a staff job, this time at the HQ of the Fighting Area based in Uxbridge. He returned to an operational job as Station Commander Northolt from January 1931 to August 1932, followed by a stint as Chief Instructor for the Oxford University Squadron, an extremely prestigious post for a "Colonial." In all these assignments, Park endeavored to fly as often and as many different aircraft as possible, amassing nearly 1,000 hours flying time despite the peacetime conditions.

From 1934 - 1936, Park was the British Air Attache in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and in 1937 served as an Air Aide-de-Campe to His Majesty King George VI before being named Station Commander at the foreword fighter station Tangmere. A severe illness in April 1938, however, cut short this satisfying assignment and also caused the Air Ministry to re-think a planned assignment to Palestine. Because of his illness, the Air Ministry sent Arthur Harris, later famous as the wartime commander of Bomber Command, in Park’s stead, while Park landed in the job initially intended for Harris: Deputy to ACM Hugh Dowding at Fighter Command. It was May 1938.

As Dowding’s second-in-command, Park was responsible for developing fighter tactics. Park rapidly grasped the need to delegate tactical decisions to the station and even squadron level. He saw the role of Fighter Command as one of collecting and sharing information, ensuring inter-group reinforcement and providing broad strategic direction rather than attempting firm control over individual units. By September 1938, the possibility of war with Germany had become obvious to all but the most naïve. Park recognized that Fighter Command lacked squadrons and, above all, modern aircraft; only five squadrons were equipped with monoplane fighters, and advocated eloquently for funds to redress the shortcomings. He also noted that radar and wireless communications were woefully inadequate, making an effective defense of Britain impossible without massive investment. Meanwhile, fighter tactics in the new environment were hotly debated.

Park recognized the need for exercises and was frustrated by Bomber Command’s lack of interest, which resulted in far too few bombers being committed to the exercises. Nevertheless, a number of weaknesses in Figter Command’s defensive tactics were identified and corrected. Park also developed the vitally important practice of first filtering “plots” (reports of hostile aircraft) before putting them on the operational map. This practice enabled duplicates and mistaken plots to be eliminated without confusing the “picture” presented to the controller. Another pressing issue was the allocation of squadrons to Groups (regions) and stations. Park successfully resisted attempts by the Commander of 12 Group to concentrate 29 of Fighter Command’s 41 squadrons in his own group, leaving only 12 for the defense of London.

In April 1940, Park was appointed commander of 11 Group, the Fighter Command unit responsible for the protection of the Southeast England from Southampton to Colchester. This area included such prime targets as the seat of the Royal Navy (Portsmouth) and the British capital. Park had not been in his position three weeks, when the Germans launched their major offensive in the West, rolling over Holland, Belgium and sweeping into France. Although the RAF had already deployed six squadrons to France at the start of the war, after the opening of the German offensive, pressure mounted for more and more RAF units to assist Britain’s allies on the Continent. Soon the RAF had deployed the equivalent of twelve squadrons to France, while four more were operating in theater from bases in England. Fortunately for Britain’s future, Dowding convinced the War Cabinet that no more pilots or aircraft could be spared if the defence of Great Britain was to be viable.

As the French army fell back and the German panzers advanced, Park and Fighter Command faced their first serious challenge. The British troops found themselves cut off on the Channel coast, and the Royal Navy launched a massive attempt to evacuate them off the continent and bring them back to England. The troops and vessels were crammed together within a small perimeter and during the embarkation process, they were both unprotected and immobile. The thus offered ideal targets to the Luftwaffe’s bombers, dive-bombers and strafing-fighters. Goering promised Hitler that his Luftwaffe would put an end to the British operation “Dynamo”.

Park and the fighters of his Group were charged with providing air protection for the evacuation. Yet, British single engine fighters of this period did not have the fuel range to remain in the skies over Dunkirk for more than a few minutes. Instead, Park attempted to use radar plots to direct his UK-based fighters to intercept and destroy the Luftwaffe’s bombers. While the RAF caused significant damage, it often engaged above cloud or at a distance from Dunkirk where their actions could not be witnessed by the troops being evacuated. Meanwhile, the bulk of the bombers were getting through. Thus, The British Army and Royal Navy suffered enormous losses during the tedious process of embarking nearly 340,000 Allied troops from the beaches of Dunkirk. Many of the troops on the ground and their officers felt that the RAF had left them in the lurch. Throughout the war, Park encountered Army officers who blamed him for not doing enough at Dunkirk.

y mid-June, as Churchill put it, the Battle of France was over, and the Battle of Britain was about to begin. In the four months that followed from mid-June to mid-October, the German Luftwaffe attempted to establish air superiority in the skies over Great Britain. It started the Battle with a marked superiority of force. Fighter Command possessed only 600 fighters; the German Luftwaffe could deplpoy 900 single-engined fighters and 300 twin-engined fighters to protect their fleet of 1,300 bombers.

The course of the Battle of Britain is widely recorded and is not the subject of this short essay. To summarize, although the RAF succeeded in destroying more German aircraft overall, the Luftwaffe fighters badly mauled the RAF. Massive increases in aircraft production enabled the RAF to replace lost fighters, but pilots could not be produced on assembly lines and casualty-rates in frontline squadrons — Park’s squadrons — rose to close to 70%. Young and inexperienced pilots were more likely to be shot down than experienced pilots, but by the end of the Battle, exhaustion was taking its toll on the experienced Flight and Squadron Leaders as well. The Battle of Britain was a very close-run battle that could easily have been lost.

Many factors contributed to victory: the courage and skill of the pilots, the dedication of the ground crews, the technological sophistication of the aircraft and the effective command-and-control system based on radar and radio communications. Too often forgotten is the leadership of AVM Park.

Park was not only making the day-to-day and minute-to-minute decisions about how many aircraft to deploy when and where, he was also making the critical decisions about squadron rotations. Because new units, unfamiliar with the conditions were usually decimated with in a short time after arrival and because experienced squadrons tended to have higher victory-to-loss ratios, rotating too many squadrons too soon would have been counter-productive. Yet even the best squadrons eventually became too exhausted and depleted to contribute to the war effort.

Park’s genius was in consistently meeting the Luftwaffe even as it changed tactics again and again. Over the four months of the Battle, the Luftwaffe altered the targets/objectives of its raids, starting with shipping and the Royal Navy, then focusing more on the radar chain, the airfields, aircraft factories and other war industries and finally on London. The Luftwaffe also experimented with a variety of types of raids: high and low altitude raids, large and small raids, diving bombing, and fighter-bombers. It tried to overwhelm Parks defenses by attacking nearly simultaneously in widely separated areas and by attacking the same targets repeatedly in successive raids. It sometimes provided massive fighter escorts for a few bombers and at other times sent over fighters on “sweeps” alone without bombers.

Whatever the Luftwaffe did, Park needed to respond within minutes. He did not have the luxury to “wait and see.” Contrary to what Park’s rival Leigh-Mallory claimed, it was not good enough to destroy the bombers after they had delivered their loads. Until the Luftwaffe started targeting London, the targets themselves were vital to Britain’s ability to repel an invasion. Had Leigh-Mallory’s tactics of assembling large gaggles of aircraft been employed, the result would have been more bomb damage to vital installations such as radar, aircraft factories, naval ships (needed to defend the Channel against invasion) and fighter airfields with their vital command and control functions and maintenance infrastructure.

In short, a different commander making wrong calls on a daily basis could have rendered Great Britain indefensible. Even with the same pilots, ground crews and aircraft, the Battle of Britain could have been lost. Another commander might have allowed pilots and aircraft to be destroyed on the ground by, for example, launching his entire force against a first raid, only for the Luftwaffe to catch them all refueling during a second. Another commander might have been over-hasty in rotating squadrons out and paid the price in lost pilots and lower kill-rates. Alternatively, another commander might have rotated squadrons too slowly, resulting in a collapse of front-line morale. Yet another commander still might have tried to hoard his fighters, avoiding confrontation with the Luftwaffe at the price of radar being knocked out, aircraft production interrupted or lamed, and the Royal Navy shattered. Undoubtedly, Park made mistakes too. No one is perfect and no one can make the right decisions all the time over four months of intense action. Yet Park was evidently right more often than he was wrong, or the Battle of Britain would have been lost.

That this was no fluke, is best demonstrated by Park’s subsequent career. In January 1942, after a year in Training Command (a critical albeit non-operational assignment), Park was commander of British air forces in Egypt, the main base for British operations in the Near East. On July 8, he was sent to take over the defense of Malta. Just two weeks after his arrival, Park launched an offensive that effectively brought an end to the daylight bombing raids on the island. At a time when Rommel was having things his way in the North African desert, Park’s defiance and successes were a major boost to British morale and duly lionized.

Park ended the war as Air Commander-in-Chief in Southeast Asia. He was highly respected and praised both publicly and privately. Over the course of his career he was awarded the DFC, MC and Bar, KBE and finally GCB. He retired with the rank of Air Chief Marshall in December 1946. Thereafter he was active in civil aviation in New Zealand. He died Feb. 6, 1975.

Although Park has only a "cameo" role in "Where Eagles Never Flew," I attempt to do credit to his leadership through discussions and references on the part of other characters to his actions and leadership style.

Buy Now - Amazon US Buy Now - Amazon UK Buy Direct from Itasca

See a video teaser at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnAoMC0d6Mo

March 8, 2021

"The Herr Reichsmarschall!" -- An Excerpt from "Where Eagles Never Flew"

Hermann Goering, C-in-C of the German Luftwaffe, was a larger-than-life character in the first decade of the Nazi regime. Widely seen as Hitler's deputy, his very flamboyance and extravagance made him seem more 'human' than the other Nazi leaders such as Goebbels, Himmler or even Hitler himself. Goering with his love of beautiful women, fast cars, yachts and aircraft was someone many could identify with. He also admired for his evident competence as the rapid expansion and successes of the Luftwaffe followed his spectacular performance as Minister of Economics overseeing the apparent wonder of economic recovery it he mid-1930s.

In this excerpt, Herman Goering has come to visit a frontline Stuka Group during the early days of the Battle of Britain.

Goering came and went in a whirlwind. He flew in with what seemed like a huge entourage. He waddled (that was really the only word for it) over to Jako, who stood in front of his pilots saluting. He patted him on the shoulder, apparently cracked a joke, and everyone within hearing laughed with him.Klaudia, Rosa and Brigitte weren’t close enough to hear, but they watched it all from the Communications Center (or CC) along with the NCOs on duty.

Was it less than a fortnight since Klaudia had been excited by the thought of seeing Goering personally? Was it less than a fortnight since she had been thrilled to think she knew a man who could ask favours of a man so powerful and favoured that the Reichstaghad created a new rank just for him, “Reichsmarschall”? It seemed a lifetime ago. The intervening fortnight had been such a roller-coaster of alternating ecstasy and despair. The expectedroses and proposalhad not come, but then Jako was the Gruppenkommandeur of a crack Luftwaffe unit in the midstof war. Klaudia kept tellingherself she should not expect too much. He had sentfor her a couple of times after duty, and his ardour and compliments reassured her again of her place in his heart. And yet…

Now, as she watched Jako grinning and nodding beside the Reichsmarshall, she felt intense – almost unbearable – pride. That was her manthat the Reichsmarshall wasjesting with like anold friend! Nor had Jakoever looked moresplendid than now inhis tailored uniform,grey gloves and leatherriding boots that gleamed in the sun.

“He’s coming this way!” someone called out.

Instantly the personnel of the CC bolted back to their respective places. By the time the Reichsmarshall reached the door,they were all intent upon their respective tasks. A loud “Achtung!” preceded the C-in-C into the room. Everyone sprang to attention.

Staff officers pouredin, and then came Goeringhimself with Paschinger still beside him. He greeted the staff of the CC by touching his glittering marshal’sbaton to the peak of his cap. He was smiling and nodding, and then he caught sight of the Helferinnen. “Ah, so you have some of our charming, brave Helferinnen here! How are they working out?”

“Jawohl, Herr Reichsmarschall. Very well, so far. May I introduce the Herr Reichsmarschall?” Jako led Goering directly to Klaudia.

There she stood, rigidly at attention, hardly daring to breathe. What could be a better sign of Jako’s good intentions than the fact that he brought the Reichsmarshall himself over to introduce him to her? She sucked in her stomach and kept her chin up; she wanted to do Jako proud.“This here is Klaudia von Richthofen.”

“Ah ha!” Goering was delighted. “I didn’t realise Wolfram had a niece! How do you like it here, Fräulein? Are my young eagles treating you properly?”

Klaudia couldn’t help smiling. “Jawohl, Herr Reichsmarschall.”

“Good, good. Glad to hear it.” Already Goering was moving on. Turning away from Klaudia and addressing Jako, he remarked, “Seeing these lovely girls reminds me of yourown charming wife, Jako. How is she doing these days?”

“In her seventh month now, Herr Reichsmarshall,” Jako answered happily, his back to Klaudia as if she didn’t exist.

“Ha!” Goering laughed approvingly. “A Christmas leave baby.”

“Jawohl, Herr Reichsmarshall,” Jako agreed, “and I hope we will have tamed the English lion in time for me to be with her at the birth.”

“Certainly, certainly,” Goering agreed as they movedaway. Klaudia wanted to scream – or just fade away into nothingness. He was married. He had been married the wholetime. Not once, not even for a moment, had his intentions been honourable. He had used her. That was all. Used her like a common whore! Rosa had been right about him the whole time. She couldn’t cope with the implications. She was ruined!Absolutely ruined. She could never go home and face her parents.

Buy now - Itasca!

Buy now - Itasca!Buy on Amazon.com!

Buy on Amaxon.co.uk!

Buy on Barnes and Noble

March 1, 2021

A very dim view of scandal - An Excerpt from "Where Eagles Never Flew"

Earlier I talked about Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding's critical role in the Battle of Britain. I argued that he has been under-appreciated. Part of the reason for that -- although he was brilliant and conscientious -- he lacked charisma. He did not have the kind of personality that enable him to connect readily with his young pilots.

In this excerpt from "Where Eagles Never Flew," Squadron Leader "Robin" Priestman, commanding a frontline Hurricane squadron at the height of the Battle of Britain has been caught on camera kissing a famous socialite -- and he doesn't think it is going to go down well with the C-in-C of Fighter Command...

The telephone rang in the dispersal, and everyone tensed. The orderly clerk emerged. “Sir,” he addressed Robin respectfully, “it’s the AOC.”

Robin dropped his head in his hands,then shoved them through his hair and dragged himselfout of the deck chair onto his feet. As he disappeared into the dispersal, all the others watched him go.

“They wouldn’t really cashier him for something like this, would they?”

“Rather depends on what they think of him generally, I suppose. Stuffy strikesme as the type to take a very dim view of scandal. I’d say he’s going to get a packet.”

“On the other hand, experienced Squadron Leaders don’t grow on trees.”

Robin swallowed before picking up the receiver, which had beenlaid beside the phone on the orderly’sdesk. In a tone of complete resignation, he reported, “Priestman.”

“Park. Would you like to give me your version of what happened?”

“I was told there were some reporters in my office who wanted to interview me, and that the Station Commander had already approvedthe interview. As I came through the door, Virginia threw herself at me and the photographer started snapping shots. I disengaged as soon as I could and got behind the desk. I did not drinka drop of the champagne, and I pushed off rather abruptly when the klaxon went.”

There was a moment of silence, and then Park remarked, “You called her Virginia just now. Do you know her well?”

“We went out a few times before the war, when I was flying in air shows, and once or twice this past winter.”

“I see. And what does your fiancée have to say about the whole thing?”

“I – haven’t– talked – to – her – yet.” Robin admitted feeling ill.

“Well, I hope for your sake – and the sake of your squadron – that she’s sensible and doesn’t make too much of this. Boret reported that you were sitting behind your desk and very correct for the part of the interview he witnessed. He praised your answers, and I quite agree that the Times article – without photo – is really quite good. I particularly liked what you said about Hurricanes, and you fielded the question about claims deftly. Your Adjutant, incidentally, gave the same version of events as you, but I have to tell you that the C-in-C is not amused. He feels it lends credence to those who portray all fighter pilots as frivolous and irresponsible. He also remarked that it wasn’t the first time you’ve been impulsive and undisciplined.”

Robin ruffled his hair with his free hand, but there was nothing he could say to that. He sighed.Park continued. “I think it will all blow over very quickly. There are more important things on our plates at the moment, to say the least. Nevertheless, I would appreciate it, if you would try to keep a low profile for a bit; would you?”

“I didn’t ask for the interview, sir.”

“I understand. Boret said you were clearlyannoyed by it all. He was afraid you might be too blunt about just how difficult things are at the moment.” There was a pause, and then Park added in a notably more friendly tone, “The PM was rather pleased, actually.”

“The Prime Minister sawit?!” Robin couldn’tgrasp his misfortune. It had only appeared in the local Portsmouth papers, after all.

“He has a large staff that sifts through the papers, looking for anything that might be of interest to him. He rang me up about 30 minutesago and growled at me that thingscouldn’t be as bad as I was making them out to be if my front-line squadron leaders had time for champagne and socialites.” Park paused and then added with obvious amusement, “He was tickled pink.”

Robin could hear Park’s amusement, but it didn’t make him feelmuch better. Churchill might be amused,but Dowding and Emilyheld his future in their hands – and he was afraid that Emily was going to react more like “Stuffy” Dowding than the amiable Churchill.

Watch a video teaser of "Where Eagles Never Flew" at: Eagles Video Teaser FINAL - YouTube

Or buy now!

Buy now - Itasca!

Buy now - Itasca!Buy on Amazon.com!

Buy on Amaxon.co.uk!

Buy on Barnes and Noble

February 26, 2021

One of the Greatest -- and Least Appreciated -- Commanders of WWII: Air Chief Marshal Dowding

To the extent that we consider the Battle of Britain pivotal to Allied success in WWII, the mastermind behind the RAF's success deserves far more credit and fame than he has been given to date. Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding

ACM Dowding was not only the commanding officer of Fighter Command during the entire Battle of Britain, he was the man who had envisioned, created, shaped and molded Fighter Command into an instrument capable of withstanding the onslaught of the Luftwaffe in 1940. Dowding had been instrumental in Training Command in the inter-war years, and for six years headed the Supply and Research Office of the Air Ministry, in which capacity he was instrumental in fostering the development of radar. He was directly responsible for inviting private tenders for ‘the fastest machines they could build’ resulting in the design of the Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire respectively. (Hurricanes are in the photo above; below the Spitfire.)

But technology and weapons are nearly worthless if they are improperly used or misused. Neither fighter nor radar would have saved England from invasion in 1940, if the institutional structures and fundamental strategy for the defense of Great Britain had not be evolved by Sir Hugh Dowding. In 1936, Dowding was appointed the first commander of the newly created Fighter Command. In this capacity, he ensured both the establishment of coastal radar stations (then known as RDF), and evolved the system of communications and control that linked that early warning system to the fighters that needed to respond.

The complex yet efficient system in which radar stations were connected by telephone directly with Fighter Command HQ, where a Filter Room sifted through and made sense of the plethora of reports and this information was converted into comprehensible plots on a map, was Dowding’s invention. The segmentation of British airspace into sectors, each protected by designated squadrons controlled and directed from a Sector Airfield with its own Control Room, was Dowding’s concept.

All the technology in the world and the best fighters would have been worthless it the information was not brought together in a timely and coherent manner that enabled commanders to make intelligent and informed decisions. The RAF did not — anc could not build with the resources at hand — sufficient fighters to patrol the skies of the UK at all times. Without this system and the military doctrine behind it, Fighter Command would have been overwhelmed in 1940.

Dowding also demonstrated foresight in advocating the training of women on radar and employing them as plotters and filterers. Women (WAAF) proved to be extremely competent, reliable and unflappable.

Last but not least, Dowding must be given credit for withstanding the immense political pressure to send more and more RAF fighter squadrons to France as the German offensive systematically overwhelmed French defenses. Had Dowding not vehemently insisted on the need to retain sufficient squadrons in Britain to ensure the defense of the realm, too many British aircraft and pilots might have been squandered in the lost Battle of France.

For all these reasons, Dowding deserves to be remembered as one of the greatest military leaders of the 20th century along with Air Vice Marshal Park, who commanded 11 Group during the Battle — but that is a different story and would require a second entry.

Dowding has only a cameo role in "Where Eagles Never Flew" which views the battle from the perspective of the frontline rather than HQ.

Buy now - Itasca!

Buy now - Itasca!Buy on Amazon.com!

Buy on Amaxon.co.uk!

Buy on Barnes and Noble

February 19, 2021

"All in a days' work" -- An Excerpt from "Where Eagles Never Flew"

The feeling of queasiness as he approached his Hurricane was familiar to Ginger now. It was his fourth patrol this week. So far, all had been uneventful, but after the fight yesterday, he was certain they were in for it now.

Ginger reached his Hurricane, and Sanders swung himself out of the cockpit and offered Ginger a hand as usual. Ginger took it gratefully with a nod and a smile of thanks. Sanders had kept his word, and “Q” had been sent back to a Maintenance Unit for a complete re-fit. Sanders was now assigned to Ginger’s new aircraft, “H,” along with the rigger, Tufnel.

Ginger no longer felt shy with either of them; they were both first-rate blokes. They seemed to like their work and were proud to keep their aircraft in the best possible condition. Sanders smiled as he helped Ginger pull the straps tight. “I hear Jerry’s getting cheeky. The blokes from 43 Squadron were telling us their pilots bagged a couple of Stukas that were going for a convoy right off the Needles.”

“I guess it had to come sometime. France surrendered a month ago,” Ginger answered stoically. Somehow when he’d joined the RAF, all he’d thought about was flying – not killing and dying.

“Good luck then, sir!” Sanders flashed him a last smile and jumped down off the wing.

“Thanks!” Ginger called after him, and then turned and waved to Tufnel to pull the chocks away. Tufnel was looking tired. He’d been up half the night helping the CO’s rigger repair the CO’s kite.

Click here to see a video teaser of Where Eagles Never Flew

Buy now - Itasca!

Buy on Amazon.com!

Buy on Amaxon.co.uk!

Buy on Barnes and Noble

February 12, 2021

The Battle of Britain - The Unsung Heroes: "Erks"

It was not the pilots alone who won the Battle of Britain. The RAF worked hard to ensure that its pilots were supported by some of the best trained ground crews in the world.

With an ‘apprentice’ program, the RAF had attracted technically minded young men early and provided them with extensive training throughout the inter-war years. In some ways, ground crews were better educated than many pilots.

Under the circumstances and given the fact that many pilots came up from the ranks themselves, it is hardly surprising that the relations between pilots and crews were on the whole excellent. The RAF had a notoriously relaxed attitude towards discipline in any case, and this further worked to break down barriers.

Last but not least, at this stage of the war, individual crews looked after individual aircraft and so specific pilots. The ground crews identified strongly with their unit – and ‘their’ pilots. After the bombing of the airfields started in mid-August, the ground crews were themselves under attack, suffering casualties and working under deplorable conditions – often without hot food, dry beds, adequate sleep and no leave. The ground crews never failed their squadrons. Aircraft were turned around – rearmed, re-fuelled, and thoroughly checked – in just minutes.

Click here to see a video teaser of Where Eagles Never Flew

Buy now - Itasca!

Buy on Amazon.com!

Buy on Amaxon.co.uk!

Buy on Barnes and Noble