Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 24

August 27, 2021

The Fate of Western Civilization in the Balance

The fate of Britain -- and indeed the entire civilized world -- hung in the balance in the critical three weeks between the launch of the German air offensive on August 12/13 and the shift in German strategy to London on September 7. Although many now dismiss the actions of the RAF and view British victory as "inevitable," this judgement based on the wisdom of hindsight denigrates the sacrifices and the demeans the accomplishments of those who fought the Battle of Britain.

At a conference of Luftwaffe commanders on August 19, the destruction of the RAF’s defensive capacity was recognized as the priority, short-term objective. To achieve this goal, when operations resumed in force on August 24, the Luftwaffe employed a variety of tactics which it varied rapidly and unpredictably to keep the RAF guessing and try to catch it off guard.

Large and small bombing raids were interspersed with fighter sweeps. Diving bombing, high-altitude and low-altitude bombing were used separately or in combined attacks. Raids were launched in the early hours of the morning, mid-day and in the evening. Sometimes the Luftwaffe struck at widely separated times and on other occasions struck at short intervals in an attempt to saturate defenses. Raids were made on widely separated targets to try to spread the RAF thin. Or, alternatively, raids were made on the same target in quick succession.

On the one hand, the Luftwaffe tried to catch fighters on the ground refueling and, on the other, to force the RAF into the air to fight with the Me109s. To achieve the latter, the Luftwaffe now and again deployed Me110s in formations to look like bombers protected by hundreds of their smaller comrades. The Luftwaffe also tried cumbersome massive raids, in one case with over 400 fighter escorts, and it tried small raids by fighter-bombers without escorts. It experimented with large formations that then split into two, three or even four smaller raids attacking widely separated targets.

Although in retrospect it is evident that many of these raids were far from effective, others were devastating. In general, the frequency and ferocity of these attacks and the much more focused targeting of RAF Fighter Command made them extremely dangerous to Britain’s air defences. Altogether 32 attacks against airfields were made in just 14 days.

On the very first day of the renewed offensive, the satellite field of RAF Manston was hit twice, taking out its communications. Bomb craters and unexploded bombs littered field and the accommodations became unusable. Park made the decision, which pilots operating from Manston felt was belated, to write the field off except for emergencies. In short, the Luftwaffe scored a victory on its very first day of the renewed offensive.

But Manston was not a Sector Airfield with an all-important Sector Operations Room. Attacks on the Sector Stations were far more dangerous attacks, and there were 22 of these between August 24 and September 6. Of these, ten raids were directed at Biggin Hill. The second of these, a low-level attack by fighter-bombers, left the Sergeants’ and the WAAF quarters destroyed along with the NAAFI and cook-house, the stores, workshops and one of the hangers. A direct hit on an air-raid shelter killed 39 airmen and women and other bombs disabled the telephone lines and disrupted the gas, water and electricity supply. Although the Sector Operations Room was unscathed, without electricity and telecommunications the controllers could not direct their squadrons. Hornchurch had to temporarily take control of Biggin Hill’s squadrons. And that was only the beginning.

On the following day, Biggin Hill was again hit twice, first by a high-level raid that did little damage, and then, at six in the evening, by another low-level raid. This raid promptly destroyed two of the three remaining hangars and, more importantly, knocked out the Operations Room. Kenley had to assume control of the Biggin Hill squadrons. Yet the next morning (September 1,) Biggin Hill was again deemed fully operational — until it was bombed yet again that evening. This time teams worked through the night to set up an emergency control room in a shop in the near-by village, and one of Biggin Hill’s squadrons was moved to the satellite airfield of Croydon. The Station Commander also took the radical decision to blow-up his remaining hangar in an effort to discourage further raids. In short, the Luftwaffe had achieved a partial victory.

Meanwhile, Hornchurch had been hit four times, Debden three times, North Weald twice, and Kenley once. In addition, the Luftwaffe had devoted some raids to attacks on aircraft factories, twice targeting Hawker Hurricane production, albeit unsuccessfully. It had also undertaken a series of concentrated attacks on Portsmouth. British civilian casualties in this period rose to their highest of the war so far, causing Prime Minister Churchill increasing concern.

With the wisdom of hindsight, historians have argued that none of this was really so terrible. They point out that the Luftwaffe continued to waste much of its effort on airfields not associated with Fighter Command (14 raids altogether) and on satellite airfields (6 raids). There has also been much written about how bomb craters and unexploded bombs don’t really render an airfield inoperable (or not for long). Likewise, damage to hangars, workshops, accommodations and other facilities have also been disparaged as “insignificant” to fighting capacity. I beg to differ.

AVM Park writing on September 12, 1940 noted that:

There was a critical period between 28 August and 5 September when the damage to Sector Stations and our ground organization was having a serious effect on the fighting efficiency of the fighter squadrons, who could not be given the same good technical and administrative service as previous. [Source: Stephen Bungay, The Most Dangerous Enemy: A History of the Battle of Britain, London: Aurum Press, 2000. 290]

Park was employing the then-common “British understatement.” First-hand accounts of the conditions under which airmen were living and working and pilots fighting leave little doubt that the impact on “efficiency” and morale was becoming severe. Squadrons were being asked to fly three to four times a day. Yet many pilots were no longer getting regular, hot meals or able to sleep in proper accommodations. Many were being forced to live off station, commuting substantial distances that thereby reduced the time available for sleep. A few more weeks of this treatment might have resulted in a different outcome. Men were reaching the breaking point as the increasing casualties underline.

Although the Luftwaffe was still losing more aircraft than the RAF, the margin had narrowed dramatically. In this two week period, 380 Luftwaffe machines were lost for 286 RAF fighters. The RAF was losing more than 140 fighters per week. At that rate, even Beaverbrook was hard pressed to keep pace, and one effective strike on a Hurricane or Spitfire factory would have wiped out the ability of the British aircraft industry to replace losses in a timely fashion.

More critical, of course, were the pilot losses that simply could not be replaced in a short space of time. By the end of August 1940, RAF Training Command was “producing” pilots with nominal training on operational fighter aircraft at a rate of 280 per month. Casualties in August, however, had been 348 pilots. The training infrastructure was not keeping up with demand.

That was not a situation that could be reversed by a change in policy or priorities. It took roughly one year to train a young man to fly monoplane fighter aircraft; there were no short-cuts or means of speeding up “production.” Volunteers from Coastal Command and the Fleet Air Arm had already been exhausted. Furthermore, turning that pilot into an effective fighter pilot took more than time — it took experience. Inexperienced pilots had a six-times higher chance of being killed than an experienced pilot. Many replacement pilots did not survive their first sortie; many more did not survive their first week.

The same was true of inexperienced squadrons. In squadrons with experienced leaders, fledgling pilots got advice, guidance and support from their more-savvy comrades. When entire squadrons without recent front-line experience were rotated into 11 Group, there were no leaders who could warn, coach and protect their charges and slaughters occurred in which six or seven aircraft were shot down in a single engagement often with the loss of several pilots. Some squadrons all but ceased to exist within a week.

But the Germans didn’t know any of this.

The Germans relied on aerial reconnaissance and the combat reports of their own pilots. As we have seen, Luftwaffe fighter pilots overestimated their victories by huge margins, while the Luftwaffe staff severely underestimated the capacity of the British industry to produce replacement aircraft. At the end of the first week of September, the Luftwaffe was again convinced that the British could have no more than 200 Spitfires and Hurricanes left.

Meanwhile, the quality of high-altitude photo reconnaissance was still quite low. It was not always possible to tell what kind of aircraft were on an airfield, let alone the extent of damage. Furthermore, the damage that threatened Fighter Command most severely — electricity and telecommunications cuts to the Operations Rooms and radar stations — were virtually impossible to detect from the recce photos. The destruction of buildings on the other hand was easily recorded and looked very impressive, even if the immediate impact was far less damaging to the RAF’s ability to keep fighting. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the Luftwaffe continued to believe that they were winning the air war against Britain.

What was starting to worry the Luftwaffe leadership, however, were their own losses. The Luftwaffe was starting to notice that it could not replace aircraft as fast as it as losing them. Some squadrons had only 50% of official aircraft strength. Serviceability rates were also down, as low as 75% in fighter squadrons. As with the British, however, the bigger problem was pilots.

While the number of fighter pilots killed on both sides was roughly equal, RAF pilots who were wounded or simply had to bail out of damaged aircraft usually landed in Britain and found themselves either in hospital or back with their units in a short space of time. The wounded usually made their way back into a cockpit within a period of weeks or months. Even in the case of severe burns, many pilots returned to flying duties after dozens of operations and plastic surgery. For the Luftwaffe, the situation was different. Because the fighting was taking place in British airspace, pilots unable to nurse a damaged aircraft across the Channel put it down in England — and became prisoners of war. Likewise, pilots who had to bail out for one reason or another became prisoners. Thus, the RAF’s pilot losses amounted to the number of pilots killed, while the Luftwaffe’s pilot losses consisted of those killed and captured.

Meanwhile, the Luftwaffe was feeling the exhaustion too. Because the Me 110 had proved ineffective, the Me109s were being asked to fly three to four sorties a day on average and as much as six or seven on some occasions. These were not short interceptions as in the case of the RAF. A Luftwaffe fighter sortie entailed a long flight across the lethal Channel — and back. Furthermore, the Luftwaffe had no system for rotating squadrons out of the front line as the RAF did. This meant that the Luftwaffe squadrons had all been engaged continuously since the start of the Battle of Britain, and often before that in the Battle of France.

In addition, in the fighter units the culture of rewarding kills resulted in the “experts” (the aces) winning medals and promotions — and receiving protection in the from of wingmen and “staff flights,” while everyone else took the casualties. This fact was increasingly resented.

Yet even more shattering to morale in fighter units was the tendency of the Luftwaffe leadership, including Goering himself, to blame the fighters for the continued attrition among the bombers. The fighter pilots knew they were giving their best, but it wasn’t enough either to destroy those “last 200 Spitfires” or to get all the bombers safely home.

If morale was starting to crumble in the ranks of the Luftwaffe’s fighter pilots, the bomber crews faced the same slow but steady erosion of elan that British and American bomber crews would learn about in the years to come. A psychiatrist specialized in battle fatigue noted after studying soldiers in both world wars that courage was like having money in a bank account: the reserves of even the bravest men could be drawn down to nothing, if demands were made upon it too often and too soon. This was happening to the Luftwaffe in 1940.

The final straw for Luftwaffe morale, however, was the absence of a powerful incentive. The men and women of RAF Fighter Command, whether flying or supporting those who did, understood that they were fighting (in the words of Winston Churchill) “a monstrous tyranny” and even more importantly (again in Churchill’s words) for “the survival of Christian civilization,” and “our own British life.” But the men in the Luftwaffe knew that no one had particularly wanted to fight Great Britain in the first place! Those that had read Mein Kampfeven knew that Hitler admired the British and the British Empire. Why on earth were they being asked to die?

Despite the successes the Luftwaffe believed they had achieved, the Luftwaffe leadership recognized that their crews were tired and did not want more of the same. Goering wanted something new, some trick, some clever new tactic that would at last “crack” the nut he firmly believed was ripe.

Goering also needed to restore his standing in Hitler’s eyes. He had promised to defeat the RAF in a couple of weeks and after two months the British were still not begging for peace talks. He had joked that if the RAF ever bombed Berlin, people could call him “Meyer.” On August 25, the RAF retaliated for bombs dropped (accidentally) on London with a more-or-less harmless raid on Berlin. Goering was about to make the worst mistake of the Battle.

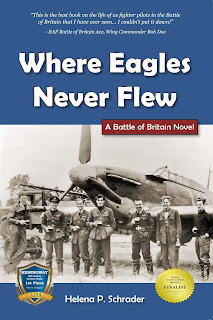

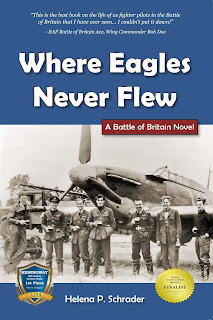

Where Eagles Never Flew opens with the Battle of France and goes on to show the Battle of Britain, in all its phases, from both sides of the Channel. It does so by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. Where Eagles Never Flew is the winner of the Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction, a Maincrest Media Award for Historical Fiction, and more. Find out more about Where Eagles Never Flew at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew or watch a video teaser at: Eagles Video Teaser

August 20, 2021

The Final Throw of the Dice - 20 July 1944

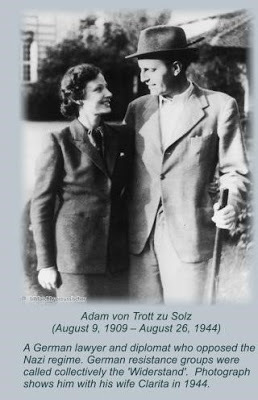

20 July 1944 saw the final attempt by the German military resistance to assassinate Hitler and bring down his murderous and corrupt regime. We all know it failed, but the reasons for that failure have often been misrepresented or misunderstood.

Early on the morning of 20 July 1944 Stauffenberg again flew to Hitler's HQ in East Prussia with the intention of killing Hitler. Nearly all the principle conspirators were informed about the imminent assassination attempt and warned to be on the alert to fulfill their assigned roles. Since the briefing at which Stauffenberg would have the opportunity to set off his bomb was scheduled for 13.00, no one expected any thing to happen before that time.

In the Wolfschanze, however, the daily briefing was moved forward by half an hour due to the expected arrival of Mussolini. Stauffenberg activated the fuses on the bomb in one of his briefcases, placed this bomb under the briefing table close to where Hitler was standing and then slipped out of the briefing hut on the pretext of making a phone call. Shortly after 12.40 an explosion took place. Stauffenberg immediately bluffed his way past the guards controlling the lock-down of Hitler's HQs. He made it aboard the waiting aircraft and took off, just moments before all aircraft at the field were grounded. He had succeeded in detonating a bomb in the room where Hitler was standing and in escaping the Wolfschanze with his life, but he had had no opportunity to telephone with Berlin. He was incommunicado until he landed.

General Fellgiebel, the man responsible for informing Olbricht about a successful assassination and then cutting Hitler's HQ off from the outside world, however, learned what Stauffenberg had not waited to find out: that Hitler had survived the blast. When Fellgiebel tried to pass this word on to the conspirators in Berlin, he discovered that someone else, the Deputy Commander of Hitler's HQ, had already taken control of all communications to and from the Wolfschanze.

Thus, it was not until 15.00 that the first news of an "incident" at Hitler's HQs reached the Bendlerstrasse. Olbricht requested more information and at about 15.30 was informed that an explosion had taken place in which several officers were severely injured. According to one version of events the cryptic message passed to Olbricht by his fellow-conspirator General Fellgiebel was: "Something terrible has happened. The Führer lives!"

In short, the only thing that was clear to Olbricht by 15.30 on the afternoon of 20 July 1944 was that the assassination had failed. It was not clear, whether Stauffenberg had been killed in his own attempt or had survived the blast only to be arrested. This put Olbricht in a terrible dilemma. After all, if Stauffenberg had blown himself up in some kind of accident, it would have been madness to set the coup in motion knowing Hitler was still alive. In such a situation, the coup might still have had a chance at a latter date with a different assassin.

Shortly before 16.00, Stauffenberg and his adjutant landed at an airfield on the outskirts of Berlin and put a call through to Olbricht, in which Stauffenberg announced to Olbricht that Hitler was dead. Olbricht went immediately to the C-in-C of the Home Army, Generaloberst Fromm, to try to persuade him, the only man authorized to issue "Valkyrie" in the event of Hitler's death, to do exactly that. Had Hitler been dead, Fromm might very well have done so, but Fromm was skeptical. He insisted on proof of Hitler's demise. Olbricht – trusting Stauffenberg's word – himself picked up the phone and put through a call to GFM von Keitel. Keitel, however, emphatically denied that Hitler had been killed. Fromm consequently refused to issue "Valkyrie." So Olbricht and his staff issued the orders illegally for a second time.

Between 16.30 and 16.45 Stauffenberg arrived back at the Headquarters of the Home Army. He reported at once to Olbricht and again - euphorically - insisted that Hitler was dead. Obviously, this was not true, but one must try to put oneself in Stauffenberg's shoes: after two unsuccessful assassination attempts, he had finally succeeded in detonating a bomb in Hitler's immediate vicinity and then, under highly dramatic circumstances, escaped alive. Stauffenberg honestly didn't know that Hitler had survived the blast. Nor did he know that Fellgiebel had failed to close down communications from OKW and that hence the entire Nazi apparatus was still fully functional.

Stauffenberg went with Olbricht to try to persuade Fromm to issue Valkyrie over his signature. A heated argument ensued in which Stauffenberg claimed, completely fancifully, to have personally seen Hitler's body carried out of the briefing hut. Olbricht then informed Fromm that "Valkyrie" had already been issued. Stauffenberg furthermore admitted that he had himself set off the bomb – to which Fromm replied that in that case he ought to shoot himself at once. Stauffenberg refused, and Olbricht confessed his complicity in the plot. According to Fromm (the only man involved in this confrontation to survive long enough to be interrogated by the Gestapo) he told Olbricht he was under arrest, to which Olbricht replied that Fromm had mistaken the situation. Two junior officers loyal to the conspirators were called and entered the office with drawn pistols. They detained Fromm under guard, while General Hoepner (as planned by the conspirators) took over Fromm's office and position. The anti-Nazi Hoepner at once started issuing orders as "Commander-in-Chief" of the Home Army.

After this, the entire coup appeared to go according to plan. Olbricht and Stauffenrberg went to work telephoning with key offices and commands, informing them of the situation, and generally driving the coup forward. They answered questions and countered doubts voiced by both the initiated and the uninitiated. One after another of the subordinate commands received and started carrying out the illegally issued orders.

But Hitler was not dead. Furthermore, the conspirators at his HQ had been unable to cut off the Wolfschanze from the outside world, and hence Hitler's entire staff, OKW, was fully operational. This meant that any commander who couldn't or didn't want to believe that Hitler was dead, could contact the Wolfschanze requesting confirmation or details. Hitler's staff, that had initially assumed that the assassination was the act of a lone man, gradually grasped that in fact a coup was in progress in Berlin.

At roughly 18.00 the first counter-orders went out from OKW. Keitel ordered that all orders signed by Fromm, Witzleben and Hoepner were null and void. Furthermore, a public announcement was made over the radio informing the German people that an assassination attempt had been made, but that it had failed.

Thereafter, calls started to come into the Bendlerstrasse from confused subordinate commands where two, contradictory sets of orders had been received. Olbricht and Stauffenberg tried to convince all these callers that the orders from OKW were the machinations of the SS in an effort to retain control of the state. The Army, Olbricht and Stauffenberg assured the military commanders, was taking over now that Hitler was dead. The implication was that the Army was finally "cleaning up" – something very many military men welcomed and supported whether they were part of the conspiracy or not.

As long as the situation remained unclear, the conspirators enjoyed a surprising degree of success. But gradually doubts grew. People started to ask themselves "what if Hitler is still alive?" Clearly, if he were dead, there was no harm in "following orders," but if he were alive and they followed the wrong orders it would mean arrest, possibly torture, and death. Under these circumstances, when officers were confronted with two sets of contradictory orders, the political sentiments of the individual became decisive. A comparison between the response to the orders in Paris and Military District II is particularly telling.

In Paris, where the Military Governor, General von Stülpnagel, was an opponent of Hitler's going back to the September Conspiracy of 1938, the orders from the Bendlerstrasse were followed willingly and with alacrity. In Military District II, where the commander was not a conspirator, he could not bring himself to follow the "Valkyrie" orders because these were "clearly treasonous" – even though he admitted that "with his heart" he was on their side.

Likewise in Berlin, it was the certainty of Hitler's survival that turned the tide against the conspirators. Most spectacularly, the always suspect (from the conspiracy's perspective) commander of the "Grossdeutschland Batallion," the unit responsible for sealing off the government district of Berlin, turned against the conspiracy - but only after speaking with Hitler personally. Major Remer first carried out his military orders meticulously. Goebbels, however, put a call through to the Wolfschanze, demanded to speak to Hitler personally, and then handed the receiver over to the awestruck major. Major Remer became Hitler's ardent supporter at once. Hitler personally promoted him two ranks and ordered him to crush the coup with his troops. From one minute to the next Remer went from keeping guard on the Propaganda Ministry to being the man determined to put down the coup.

Had the conspiracy succeeded in a having one of their own – say Axel von dem Bussche – in command of the "Grossdeutschland Batallion" on 20 July 1944, maybe even Hitler's survival would have been immaterial. But for the vast majority of German officers – just as GFM v. Kluge had foreseen back in early 1943 – Hitler's death was the absolute prerequisite for action against the regime.

Even in the Bendlerstrasse itself, the increasing certainty that Hitler was alive eroded the support that Olbricht and Stauffenberg had initially enjoyed among their respective staffs. Several officers of GAO decided it was time to go to General Olbricht and find out directly from him what was going on. They confronted Olbricht at around 22.30 - fully armed since they had been asked to take over guard-duty. As these officers assured me personally, they did not come in with pistols drawn and they did not threaten General Olbricht. They still trusted him, but they no longer believed that they had been told the whole truth.

At this inopportune moment, Stauffenberg sought Olbricht out. Seeing the other officers with their weapons, he decided to flee. One of the officers shouted after Stauffenberg, ordering him to halt. Stauffenberg did not. Shots were fired. Stauffenberg was wounded.

Olbricht was now arrested and escorted by several of these staff officers to where Fromm was still being held in custody by junior officers loyal to the conspiracy. Fromm was released and immediately ordered the known conspirators – Beck, Olbricht, Stauffenberg, and two others - arrested. Without the slightest adherence to legal niceties, he summarily found them guilty of High Treason and sentenced them to death. Beck asked permission to shoot himself, and was granted this right.

Meanwhile, the other four officers were taken down the winding, red-marble stairway from the GAO into the courtyard of the Bendlerstrasse. A firing squad was hastily improvised and the south wall of the courtyard was lit by the headlights of staff cars. The first four conspirators, Friedrich Olbricht, Claus Graf Stauffenberg, Albrecht Ritter Mertz von Quirnheim and Werner von Haeften, were shot shortly after midnight. More than 5,000 other conspirators and sympathizers followed them to an untimely death in the months to come. The attempt to free Germany of the Nazis from within had failed.

The Courtyard of the General Staff HQ where Olbricht, Stauffenberg and others were executed without trial

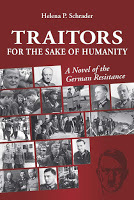

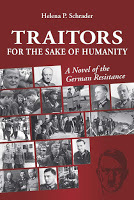

The Courtyard of the General Staff HQ where Olbricht, Stauffenberg and others were executed without trialThe German Resistance to Hitler was the subject of my PhD thesis. At the time I was the first Western academic granted access to some military archives and documents in what was then still "East Germany." In addition, I conducted interviews with over one hundred survivors of Nazi Germany, both supporters and opponents of the regime. The research culminated in a published dissertation and, later, an English-language biography of General Friederich Olbricht based on the dissertation. It also inspired me to write a novel about the German Resistance, which was recently re-released in ebook format under the title: "Traitors for the Sake of Humanity." Find out more and read reviews of "Traitors" at the publisher's website: Cross Seas Press.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

August 13, 2021

Eagle Day and the Air Assault on Britain 1940

Churchill had predicted the start of the Battle of Britain as early as June 18, but in the event it was August 12/13 before the Luftwaffe launched a serious assault. Throughout July it had held back its strength, probing RAF defences while anticipating a diplomatic end to hostilities. All that changed August 13, 1940.

The Nazis, so fond of Wagnerian opera, called the opening of their air offensive “Eagle Day.” The objective of this phase of the Battle was to destroy the ability of the Royal Air Force to defend British air space. The targets of the offensive were first and foremost the RAF airfields themselves, but also British aircraft industry to shut down fighter production, and the radar installations vital to command and control of Britain’s fighter forces.

The Nazis, so fond of Wagnerian opera, called the opening of their air offensive “Eagle Day.” The objective of this phase of the Battle was to destroy the ability of the Royal Air Force to defend British air space. The targets of the offensive were first and foremost the RAF airfields themselves, but also British aircraft industry to shut down fighter production, and the radar installations vital to command and control of Britain’s fighter forces.

The Luftwaffe opened its main offensive against British air defenses with high morale. According to their calculations, during the previous month (July 1940) they had achieved a “kill ratio” (number of enemy aircraft shot down per friendly aircraft lost) of 5:1. That is, they believed that they had destroyed five RAF aircraft for every Luftwaffe loss. German intelligence, meanwhile, underestimated British aircraft production by 50% — that is they believed the British aircraft manufacturers were delivering only 250 fighters per month when, in fact, under Lord Beaverbrook’s management British aircraft factories were producing 500 Hurricanes and Spitfires every month.

On the eve of Eagle Day, to pave the way for the main assault, the Luftwaffe targeted Britain’s “eyes” — the radar installations along the coast. In the early hours of the morning, the Luftwaffe’s Test Flying Wing (Erprobungsgruppe) 210 attacked the radar stations at Dover, Pevensey and Rye, putting all three out of action. Fighter Command was blind from East Kent to West Sussex. Notably, the Test Flying Wing consisted of Me110s and Me109s converted into fighter bombers. They came in fast and low — and all returned without encountering a single British fighter.

Later that same morning, a force of bombers larger than anything seen up to this point made a determined attack on both Portsmouth and the Ventor radar station on the Isle of Wight. Last but not least, the Luftwaffe hammered RAF forward airfields at Manston, Lympne and Hawkinge, all three of which temporarily rendered unusable.

As the day ended, the Luftwaffe believed they had shut down four radar stations, rendered three airfields inoperable and destroyed (they claimed) forty-six Spitfires and twenty-three Hurricanes. In fact, by the end of the day, the airfields were all again operational. Of the radar stations, the three mainland radar stations were back on the air; only Ventor would remain inoperable for three more days. As for the RAF, “only” twenty aircraft had been destroyed in the air, although some aircraft were lost on the ground in the attacks on the airfields.

An aircraft destroyed on the ground. Photo courtesy of Chris Goss.

“Eagle Day,” August 13, dawned with uncertain weather and Goering ordered the great assault on Great Britain postponed until the afternoon. However, the postponement orders only reached some of the units designated to participate, resulting in these staying on the ground or turning back, while others proceeded — with inadequate fighter escort. The low cloud that had induced Goering to want to postpone the operation provided some protection, but eventually the bombers were found and five bombers were shot down for the loss of a single Spitfire.

Bizarrely, however, all the attacks carried out were against comparatively unimportant targets. The bombers went for Eastchurch, which was a Coastal Command station, and raided the airfields at Farnborough and Odiham, neither of which were used by Fighter Command. Me110s also undertook a free sweep that resulted in the loss of six of their number but claimed nine Spitfires. In fact, they had tangled with the Hurricanes of 601 Squadron, which suffered only one aircraft lost and two damaged in the engagement. (The claims of Spitfires shot down was “Spitfire snobbery,” i.e. the Luftwaffe’s perpetual refusal to recognize how deadly the Hurricane was and for pilots to dogmatically insist were dog-fighting with “Spitfires” even when they were facing Hurricanes.)

At 14:00 the units that had received the postponement orders took off at last and proceeded in large numbers to again assault airfields the Luftwaffe apparently considered vital: Boscombe Down, Worthy Down, Andover, Warmwell, Yeovil, Rochester, and Detling. Readers familiar with the Battle of Britain will note that none of these airfields were vital Fighter Command Sector Airfields. From the latter, the RAF dispatched fighters to intercept the intruders, bringing down 47 aircraft altogether.

At the end of the day, the Luftwaffe leadership was acutely aware that the mix-up about timing had hurt them and cost them lives and aircraft, but they consoled themselves with the “fact” — unfortunately largely self-fabricated — that they had destroyed 84 RAF fighters. The correct figure for RAF losses were 13 aircraft lost in the air and one on the ground. RAF pilot losses amounted to just three. The RAF had handily won on Eagle Day — the Germans just didn’t know it yet.

August 14 was comparatively quiet as the Luftwaffe prepared for their next “big” day. This was to be a broad attack along the entire south coast of England and — exceptionally — including Luftwaffe units based in Norway and Denmark against targets in the North of England. The Luftwaffe assumed that the RAF had only been able to put up such a spirited defense in the southeast over the previous weeks because it had denuded the rest of the country of fighters. The Luftwaffe remained confident that the Me110s, which had the range to carry out missions over the distances involved, would now prove their worth.

The targets were again predominantly airfields, although a factory producing Stirling bombers was also hit. The factory was so badly damaged that production was halted for three whole months, but the impact on the Battle of Britain was nil. Other attacks were more significant. Martlesham Heath was put out of action for 48 hours and bombs intended for Hawkinge severed the power cables to the radar stations at Rye, Foreness and Dover, again blinding Fighter Command in this vital sector for a whole day. Also, toward the end of the day, raids were sent against Kenley and Biggin Hill — the first time Sector Airfields essential to Fighter Command’s ability to defend the country were targeted.

The results for the Luftwaffe were shockingly disappointing — and this time they knew it. The northern raids had been intercepted early, forcing many bombers to drop their loads into the sea, while the Me110 again proved completely incapable of providing an effective protection to the bombers. The raids on the south had provoked a savage response and many of the targets had been missed. Critically, instead of Biggin Hill, the Luftwaffe had bombed West Malling, a satellite airfield still under construction, and instead of Kenley they had hit the satellite airfield at Croydon. Altogether the Luftwaffe had flown 2,000 sorties and lost 75 aircraft, including some key senior officers.

While the Luftwaffe’s loss rate of 3.75% was far below what RAF Bomber Command and the U.S. Eighth Airforce would endure at the height of the Allied bombing offensive, it was sobering to an air force that had believed it was handily winning the air war against Britain. August 15 went down in Luftwaffe history as “Black Thursday.”

Goering drew some lessons from the disaster. The Stukas, he concluded, needed to be defended better — by three full Gruppe of fighters. He also ordered fresh fighters to meet the waves of bombers coming out, recognizing that the escort fighters would be nearly out of fuel and unable to engage on the return leg. Goering also stipulated that the focus of all future attacks must remain the RAF and the aircraft industry, but he made a serious error. Believing that successful attacks on airfields rendered them inoperable for at least 24 hours or more, he ordered that the same airfields should not be targeted in quick succession. In fact, even airfields that were badly hit were usually operational again within hours. By stopping attacks in quick succession, Goering gave the RAF fighter stations a breather. Overall, however, the pressure was to be maintained.

On August 16, the important Sector Airfield of Tangmere was badly hit and so was the Ventnor radar station. The former was only temporarily inoperable, but Ventnor was knocked off the air for seven days. Other targets that day were the Portsmouth docks, Manston, and the non-Fighter Command airfields at Lee-on-Solent and Brize Norton. At Tangmere the Stukas were attacked by Tangmere based squadrons with such viciousness and effect that 70% of the Stuka unit engaged was wiped out. Nevertheless, based on the intelligence reports received and (false) assumptions about aircraft production, the Luftwaffe General Staff concluded that the RAF had at most 300 operable fighter aircraft left. In fact, there were 855 serviceable aircraft with front line squadrons alone, and another 363 fighters available at training units and maintenance units.

But ignorance is bliss and the Luftwaffe prepared for another “big” day: August 18. The Luftwaffe saw no need for an early start, and it was not until mid-day that the Luftwaffe assembled their air armadas. Large numbers of He 111s, Do 17s and Ju 88s were detailed to attack Kenley and Biggin Hill, protected by no less than 410 Me 109s and 73 Me 110s. The Luftwaffe’s plans also called for a three-stage attack composed of 1) an initial dive bombing attack to destroy ground infrastructure, followed by 2) a high-level attack to shoot down RAF fighters that came up to defend their airfield, and finally 3) a low-level raid to finish the station off with strafing as well as bombing.

Unfortunately, even the best-laid plans can go wrong. Cloud resulted in some confusion and the low-level raid without fighter escort reached the target first, only to encounter the full fury of the defenders. When the other bombing contingents put in their appearance, however, the RAF was soon stretched and fighting so hard that several fighters were lost to friendly ground fire. Furthermore, some of the German fighter commanders had figured out that Manston was used for refueling RAF fighters. They decided to strafe the field on their way to escort returning bombers. They caught four RAF fighters on the ground.

Meanwhile, farther west, Luftflotte 3 sent Stukas against the non-Fighter Command airfields of Gosport, Ford and Thorney Island and the radar station at Poling. Fighter Command was able to muster six squadrons to oppose these raids and the Stukas were again slaughtered. Seventeen were destroyed and six damaged, while eight of the escorting Me 109s were also shot down. The RAF on the other hand had lost five aircraft but only two pilots. Although the Luftwaffe could not know the the RAF’s losses, they did know that one of their Stuka groups had sustained 50% casualties — and this after losses of 70% in the raid on Tangmere two days earlier. Such losses were not sustainable regardless of the successes.

The last raids of the day targeting Hornchurch and North Weald took off at 17:00. The RAF went up in force to meet them and was understandably gratified when the bombers turned back. The reason for the retreat, however, was cloud cover over the targets rather than fear of the RAF. Only four bombers were lost, but ten of the Luftwaffe’s escorting fighters were shot down for a loss of nine RAF fighters.

Altogether on August 18, the Luftwaffe lost 69 aircraft destroyed and 31 damaged in order to knock out 34 RAF fighters and damage 39. Furthermore, since the opening of the offensive, the Luftwaffe had lost roughly 300 aircraft, thirty percent more than in the entire previous month. Yet Goering’s response to the situation was essentially “more of the same.”

To be sure he promoted his top-scoring aces to “Kommodores,” reorganized the units, changing who was responsible for what, and also moved them around a bit geographically, but Goering made few changes in tactics. RAF Fighter Command remained the principal target, with the aircraft industry, other RAF bases and the Royal Navy as secondary targets to be attacked when circumstances were “right.” He pulled back his Stukas and allowed his fighters a little more leeway for free hunting rather than insisting on specific escort ratios, but he also made it abundantly clear that he wanted his bombers protected and the escorts would be blamed for unacceptable losses. A spell of bad weather then set in that gave both sides a breather before the battle continued again.

Where Eagles Never Flew opens with the Battle of France and goes on to show the Battle of Britain, in all its phases, from both sides of the Channel. It does so by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. Where Eagles Never Flew is the winner of the Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction, a Maincrest Media Award for Historical Fiction, and more. Find out more about Where Eagles Never Flew at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew or watch a video teaser at: Eagles Video Teaser

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

August 6, 2021

Fateful Failure on July 15, 1944

While the deteriorating war situation increased the likelihood of public acceptance of a coup, it also made action against Hitler increasingly imperative. Meanwhile, time was running out in another respect as well: the Gestapo was closing in.

In April 1943, Hans Oster, the conspirator inside German Counter-Intelligence department responsible for obtaining plastic explosives, was suspended from duty. One of his subordinates had been caught in a currency violation, and the Gestapo smelled something "fishy." Meanwhile, Tresckow had been promoted; his staff dispersed. On one of the three military cells of resistance remained: that at the General Army Office under General Friedrich Olbricht

Olbricht, meanwhile, had been burdened with more official responsibilities. He was no responsible not only for replacing materiel losses of the army but of the SS, Luftwaffe and Navy as well. He also also held command responsibility for weapons development, including both the V-1 and V-2. The official demands on his time and the need to travel made it impossible for him to manage all the details of the assassination and coup planning on his own. He needed a "reliable" – anti-Nazi – assistant. He consulted with Beck and Tresckow and other conspirators and eventually settled on a young Lieutenant Colonel of the General Staff, with whom his staff had worked well in the past, Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg.

Stauffenberg was known as a good organizer. He had served in subordinate staff positions his entire career, and was never decorated. Although briefly with a Panzer division in France as Second General Staff Officer (Logistics), he did not particularly distinguish himself here and was transferred to a job in Berlin in the middle of the campaign. He served in the Organisation Department of the General Staff in Berlin for more than two and a half years before being given the job of Second – later First – General Staff Officer of a division with Rommel's Africa Corps. Here he was severely wounded, losing an eye, a hand and three fingers on the remaining hand.

Up until this point, Stauffenberg's attitude toward the regime had varied from enthusiastic (at the time of Hitler's assumption of power and his victory over France) to hate-filled. By the time Stauffenberg was lying in a hospital recovering from his wounds, he had convinced himself that Hitler was leading Germany to utter destruction and that he had to be stopped at all costs, but, until he walked into Olbricht's office in August 1943, he did not even know there was a military conspiracy.

When informed about the conspiracy headed by Beck, Stauffenberg readily agreed to join and threw himself into his new job with great energy and will-power. His position at GAO was deputy to General Olbricht, and he had exactly the same function and position inside the conspiracy – not as some biographers of Stauffenberg would make one believe, the other way around. At no time did Stauffenberg question that Olbricht was his senior in both military and resistance matters. Nor did Stauffenberg attempt to usurp Olbricht, Beck or Tresckow's roles as leaders of the military resistance. But Stauffenberg did take an informally leading role in the conspiracy because Olbricht had delegated it to him. Olbricht's official duties required his presence at meetings, conferences, briefings and inspections all over the Reich. Olbricht could no longer devote enough time to coup planning – that was now Stauffenberg's job.

There is no doubt that Stauffenberg attacked these duties with invigorating élan and energy. He had to. He had already wasted a lot of time. Up until his fateful meeting with Olbricht in August 1943, Stauffenberg had said a lot about how Hitler ought to be shot (by someone else) or argued that the command structure ought to be altered (by the Field Marshals), but he hadn't done anything. On the contrary, he had continued to believe in Hitler's ability to win the war and supported Hitler as long as he thought he might still win the war.

Like any new convert, however, once Stauffenberg changed sides and committed himself to the conspiracy, he was particularly zealous. Almost equally important, Stauffenberg had not experienced the failures, set-backs and disappointments that the others had endured. And since at the time of Stauffenberg's arrival at GAO Plan "Valkyrie" had just been updated, Stauffenberg's primary assignment as Deputy Chief of Staff of the Military Conspiracy against Hitler was to organise the dictator's assassination.

Despite Stauffenberg's undoubted persuasive powers and dedication, none of the various assassination plans he originated between October 1943 and July 1944 came to fruition. By July 1944, the situation on the front had deteriorated so dramatically and the mounting atrocities throughout the occupied territories were so unbearable that the military resistance was driven to the last extreme.

None of the leading members of the conspiracy – least of all Beck or Olbricht - doubted that the war was lost – with or without Hitler. Most recognised that the Allies would insist on Unconditional Surrender even from a post-Hitler government. But the Gestapo was closing in even more closely on the conspiracy. Key sympathizers, men who knew far too much about what the military was planning – James Graf Moltke, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Julius Leber and Wilhelm Leuschner – had been arrested. The leaders of the military resistance decided that the chances of success were no longer irrelevant. The German Resistance had to act soon - if only to demonstrate to the world that it existed.

When on 1 July 1944, Stauffenberg (with the full complicity and approval of Olbricht) moved into the position of Chief of Staff to the C-in-C of the home army, Stauffenberg abruptly gained personal access to Hitler. He at once decided to carry out the assassination himself. On 11 July 1944, Stauffenberg was ordered to report to Hitler's HQ on very short notice. The conspirators had time to alert only a few of the key conspirators, and it was agreed that – given the inadequacy of the preparations - Stauffenberg would only make the assassination attempt if Himmler and Göring, Hitler's most likely replacements, could be killed at the same time.

When Stauffenberg got to Hitler's HQ and realised that neither Himmler or Göring would be present at the briefing, he put a call through to Olbricht. Either – as the Gestapo reported based on their investigation – to report to Olbricht the absence of Hitler's deputies or – as many historians describe it – to ask for Olbricht's permission to carry out the assassination any way. Olbricht allegedly said ‘no.' In any case, Stauffenberg returned to Berlin without having attempted the assassination. In consequence, a variety of preparatory actions had to be cancelled.

It is important to note this sequence of events because in much of the literature an identical description of events often appears under the date 15 July 1944. However, in the aftermath of this aborted assassination attempt Stauffenberg, Olbricht and Beck jointly decided that there would be no repeat of the events of 11 July 1944. Instead, it was agreed that the next assassination attempt against Hitler would be made regardless of whether Himmler and/or Göring were present.

As soon as Stauffenberg knew the date of his next trip to Hitler's HQ, 15 July 1944, comprehensive preparatory measures were undertaken and a long list of conspirators and partial conspirators alerted of upcoming events. Furthermore, because the army units needed for "Valkyrie" were stationed farther away than the SS units loyal to Hitler, it was decided that the "reliable" army units should be given a head-start. The best way to effect this was to issue the lowest level of preparedness for "Valkyrie" – Alarm Level One – for the Berlin Military District roughly two hours before the earliest possible time for an assassination attempt.

To do this, Olbricht had to issue the "Valkyrie" orders illegally, since he was not authorized to issue them at all. Furthermore, since the issuance of orders is a highly visible act involving hundreds of troops and cannot be kept secret, it was clear that in the event the assassination failed, suspicion would fall immediately on Olbricht – no one else. Such a risky course of action could only be justified if everyone agreed in advance that there would be no conditions, no uncertainties: Stauffenberg would set off the bomb on 15 July 1944.

Stauffenberg flew to Hitler's HQ on July 15, arriving at 11 am. At 13.10 the daily briefing began but it was cut short to enable a second briefing, at which Stauffenberg was required to make a presentation, to be held immediately afterwards. The second briefing lasted until 14.20. As Stauffenberg explained the situation to his brother and co-conspirator Berthold Graf Stauffenberg, he had "absolutely no opportunity to attempt the assassination."

In the meantime, however, as agreed by the conspirators, the "Valkyrie" Orders, Alarm Level One, had been issued for the Berlin Military District. Alarm Level One required the designated units go on alert and await further orders. When Stauffenberg got out of his second briefing in the Wolfschanze without having had a chance to carry out the assassination attempt, he at once called Olbricht to report. This conversation was witnessed at both ends: by Stauffenberg's escort at Wolfschanze, Oberleutnant Giesberg, and in Berlin by General Hoepner, who was with Olbricht when he received the call. Both men survived 20 July 1944 long enough to be interrogated by the Gestapo. Both confirm that the conversation took place, and Hoepner further stated that the content of the call was only that Stauffenberg had been unable to take action.

In the literature about 15 July 1944, however, another telephone call is often described. People, who were no where near the two men involved in the conversation, claim that Stauffenberg called Olbricht before going into the first briefing to report that Himmler and Göring were again absent and ask if he should still go ahead with the assassination. It is unclear why he should do so when it had been agreed in advance that he would act "regardless" – unless one wishes to imply that Stauffenberg lost his nerve. To make the account even less logical, it is then claimed that - although the "Valkyrie" orders had already gone out illegally and Olbricht had thereby already exposed himself - Olbricht suddenly changed his mind and advised against taking action. Adding a final absurdity to the whole story, Stauffenberg is then supposed to have asked his own adjutant for advice and on the recommendation of a subaltern (but against the advice of his superior) decided to do what he had promised to do before leaving Berlin. This version of events is not sustainable either logically or based on the evidence and testimony of witnesses. It can be explained, however, by survivors who were not witnesses confusing the happenings of 11 July with those of the 15th. (For a more detailed rebuttal to these allegations please refer to either of my full-length biographies of Olbricht .)

Undisputed is the fact that Olbricht was informed at roughly 14.20 that the assassination had not taken place. At the time Olbricht received this call "Valkyrie" Alarm Level One had already been in effect for three and a half hours. Olbricht had to instantly find a way to call off "Valkyrie," prevent discovery of the coup, and if possible save "Valkyrie" for use at a later date. He immediately set off on an "inspection tour" of the various "Valkyrie" units.

Olbricht visited each of the "Valkyrie" units, inspected their state of readiness, and gave short addresses at each unit, explaining the (official) purposes of "Valkyrie." While he seemed to get away with passing off the alarm as an exercise and the Gestapo later expressed amazement that the entire deception functioned so flawlessly, the results of the pre-mature issuance of the "Valkyrie" orders were overwhelmingly negative. The bottom line was that Olbricht was not authorized to issue "Valkyrie" – not even as an exercise. Olbricht's immediate superior, the C-in-C of the Home Army was furious, and Olbricht was subjected to a severe dressing-down. Worse: the "Valkyrie" Alarm on 15 July 1944 attracted the attention of both Keitel, the Chief of Armed Forces High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht), and the Commander of the SS, Heinrich Himmler. These two men, fanatically loyal to Hitler, wanted to know exactly what was going on.

It was clear to all conspirators that Stauffenberg had to act the next chance he got "regardless" – and equally obvious that next time there could be no issuance of the "Valkyrie" orders until it was 100% certain that Hitler was dead.

The events of 15 July 1944 are described in detail in "Traitors for the Sake of Humanity." Find out more and read reviews of "Traitors" at the publisher's website: Cross Seas Press.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

July 30, 2021

Trying to KIll Hitler -- The Assassination Attempts of 1943

While a fascist dictatorship can transform the simplest acts of human kindness into acts of courageous opposition by making human decency and compassion crimes, no dictatorship has ever been toppled by kindness. Once a dictator is entrenched and surrounded by a fascist state, only force will end it. It took the combined military might of the United States, the Soviet Union and the British Empire to destroy Hitler's fascist state. Another form of force would have saved millions and millions of innocent lives -- not just the Allied soldiers that fell in the liberation of Europe, but the victims of Nazi racism in the death camps. Namely, a military coup d'etat.

In a dictatorship, such a coup is predicated on the elimination of the "Leader" adulated by the gullible majority. We know of at least 42 different plans to assassinate Hitler. They all failed for one reason or another. One of these attempts stands out for its sheer genius, while two others deserve an "honorable mention." All were made in 1943.

The Staff of Army Group Center; Tresckow standing on the far right.

The Staff of Army Group Center; Tresckow standing on the far right.

At the Headquarters of Army Group Centre on the Eastern Front, the First General Staff Officer, Oberstleutnant Henning von Tresckow, collected around himself a staff of like-minded officers - men fundamentally opposed to the criminal Nazi regime. Even before the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Tresckow had been shocked and appalled by the criminal nature of the orders issued to the subordinate commands. He recognised that such orders as the "Commissar Order" and the "Barbarossa Instructions" were clear violations of international law, and he convinced his commander, Feldmarschall von Bock to protest to the C-in-C of the Army, Generaloberst von Brauchitsch, but to no effect. By the winter of 1941, he and the men around him at Army Group Centre Headquarters had seen exactly where these barbaric orders led: to atrocities against the helpless and unarmed, whether prisoners of wars or Russian civilians. After becoming witnesses to a large-scale massacre of Jews, Tresckow decided that Hitler and his regime could be tolerated no longer. Hitler had to be eliminated – like a mad dog.

Tresckow sent one of his staff to Berlin with the mission of finding if there wasn't anyone left in the German capital who was as determined as he to eliminate the Nazi dictatorship. The trail led – logically – to Generaloberst Beck, and Beck put Tresckow in touch with both Oster and Olbricht. Henceforth, the Conspiracy had three central operative cells: Oster in Counter Intelligence, responsible for the assassination, Olbricht in GAO, responsible for planning the coup that would follow the assassination, and Tresckow in Army Group Centre, responsible for recruiting a active Field Marschal who would lend his name and troops to the coup.

By the autumn of 1942, however, Tresckow had still not managed to talk his superior, Feldmarschall von Kluge, into condoning treason. Kluge fundamentally sympathized with the sentiments of his staff, but he shied away from treason in time of war. Olbricht, impatient for action, suggested they could wait no longer, and must rely on the troops of the Home Army alone to carry out the coup after a successful assassination. At almost the same time, however, the Gestapo started showing excessive interest in the activities of the Counter-Intelligence Department. Oster was forced to suspend his resistance activities, and Tresckow therefore assumed responsibility for the assassination planning.

The winter of 1942-1943 brought the reverse in Germany's military fortunes that the military resistance leaders had long anticipated. With the tragedy of Stalingrad already in the offing, the military conspirators wanted to be ready to exploit the inevitable shock on the part of the population that was due to follow. Olbricht explicitly asked Tresckow to give him eight weeks time to get the coup plans (which had been much neglected during the summer of German victories) up-to-date. At the end of February 1943, Olbricht passed the word to Tresckow: "We're finished. The trigger can be pulled."

Tresckow was ready. He had at last succeeded in winning over the support of GFM v. Kluge. Kluge - in despair over Hitler's dilettantish and stubborn command style during the disastrous winter of 1942-1943 - was ready to put himself and so his entire Army Group in the service of the coup on the condition that Hitler was dead. More important, however, Kluge had managed to convince Hitler's staff that the dictator should personally visit Army Group Centre.

Generalfeldmarschall Gunther von Kluge

Generalfeldmarschall Gunther von KlugeOnce Hitler had committed himself to visiting Army Group Centre, Tresckow's only problem was deciding how to kill him. There were various options. Individual officers on (or closely associated with) his staff, notably Georg Freiherr von Boeselager, were extremely good marksmen. Boeselager volunteered to shoot Hitler at close range. But Tresckow knew that Hitler would be surrounded by loyal henchmen and body guards. It would be comparatively easy to overpower a lone assassin or disrupt his aim simply by jostling him or yanking the dictator out of danger at the right moment.

Georg Freiherr von Boeselanger

Georg Freiherr von BoeselangerThe idea therefore evolved into a joint assassination in which all members of the conspiracy attending the luncheon for Hitler would collectively shoot him. Yet on the day of Hitler's visit to Army Group Centre, 13 March 1943, Hitler ate his meal surrounded by officers determined to murder him without suffering any harm. Why? Because Oberst von Tresckow had come up with a far better idea.

From Oster, Tresckow had obtained captured British plastic explosives. These he fashioned into the shape of a cognac bottle, wrapped like a gift, and then – having watched Hitler board the aircraft waiting to fly him back to Berlin - asked another officer in the very act of boarding to take the package back to Berlin as a gift to a mutual friend. The explosive had a 30-minute fuse, and Tresckow set this off before turning the package over to the innocent "courier."

It was the perfect assassination plan. If all had gone according to plan, the bomb would have exploded while Hitler's plane was flying over territory controlled by Soviet partisans. The aircraft would thus have crashed deep inside partisan territory, and it would have taken days to recover the pieces much less start an investigation. Meanwhile, Hitler would have been dead, and the "Valkyrie" orders would have long since have been issued completely legally.

Furthermore, because the explosives used were British, the initial suspicion would have fallen on foreign saboteurs rather than domestic opponents. Meanwhile, the military resistance would executed the secret aspects of "Plan Valkyrie," i.e. attacking the organs of the Nazi state, while the SS and Nazi Party were still stunned by the loss of their "infallible leader" – if they weren't bitterly fighting one another to succeed him. The population at large would most likely have supported the army because their faith in the Nazi leadership had been shattered by the recent loss of an entire army at Stalingrad. The increasing devastation of German cities caused by the Anglo-American air offensive was also taking its toll on German moral and loyalty to the regime. The Army on the other hand still enjoyed immense prestige – particularly compared to the increasingly obvious corruption and egotism of low-level Nazi officials.

But although the detonator worked, the explosives failed to ignite. The explosion did not take place. Hitler's aircraft landed safely. Tresckow had to call the alleged recipient of the "gift" and retrieve the bomb before it could be discovered and suspicions aroused.

The "perfect" assassination had failed, but the necessity of assassinating Hitler remained.

Just eight days later Tresckow found a second opportunity to try to kill Hitler. A representative of Army Group Centre staff was requested to be present in Berlin at the festive opening of an exhibit of captured Soviet equipment and weapons. Hitler was scheduled to open the exhibition, and one of the conspirators, Rudolf-Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff, volunteered to carry out a suicide attack on Hitler.

Rudolf-Christof Freiherr von Gersdorf

Rudolf-Christof Freiherr von GersdorfGersdorff's initial plan was to attach the explosives to the podium where Hitler was scheduled to speak. But Gersdorff was unable to get near the podium in advance of the event. Unsure where else Hitler was likely to linger, Gersdorff decided instead to carry the bomb in the pocket of his greatcoat as he escorted Hitler about the exhibition. But Hitler did not linger. He rushed straight through the exhibition without stopping even once - despite Gersdorff's efforts to attract the dictator's attention to one thing or the other. When Hitler departed the exhibition, Gersdorff could no longer stay near him. The dictator's "sixth sense" appeared to have warned him of the danger, and Gersdorff barely had time to rush a toilet and defuse the bomb.

While this assassination plan was not so perfect as the one in the aircraft, nevertheless it had clear chances of success given the mood in Germany at this time, so shortly after the surrender at Stalingrad. Again the use of English explosives would have deflected suspicions from the German Army and certainly no one had any reason to associate a low-level staff officer from Army Group Centre with General Olbricht and "Valkyrie."

Despite this second failure, the military conspiracy did not lose heart. Over the next months, a number of other officers offered to sacrifice themselves in order to kill Hitler, but for a variety of reasons, none of these men came close to carrying out an assassination until in November 1943. Then Axel von dem Bussche agreed to model the new uniform designed for the Eastern Front before Hitler personally – and use the opportunity to eliminate the dictator.

Axel Freiherr von dem Bussche, 1942

Axel Freiherr von dem Bussche, 1942Bussche wanted no English plastic explosives with a long fuse. His plan was to pull the "plug" on a standard-issue German hand-grenade and then clasp Hitler in his arms until they were both blown to pieces. Bussche went to Hitler's HQ in East Prussia, the so-called "Wolf's Lair" or Wolfschanze, and waited for the arrival of the uniform he was to model. It didn't come. It had been destroyed in an air-raid. Bussche's home leave expired and he had to return to his unit on the Eastern Front. Here he was severely wounded and soon lost a leg. He was lying in an SS hospital – with the plastic explosives he had decided not to use in a suitcase under his bed - on 20 July 1944. His wounds – and the fact that other conspirators did not betray his name even under Gestapo torture – saved his life. But until his death from natural causes decades later, he blamed himself for his failure.

My novel, "Traitors for the Sake of Humanity," depicts the difficulties of assassinating a dictator surrounded by fanatical followers -- among other things. Find out more and read reviews of "Traitors" at the publisher's website: Cross Seas Press.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

July 23, 2021

Planning a Coup 1942

While many isolated individuals remained vehement opponents of Hitler, as long as Hitler was enjoying near bloodless victories and expanding German power, wealth and territory, it was impossible to consider a coup against him. It was not until the Wehrmacht stalled and was temporarily thrown back in the winter of 1941/1942 that Hitler's bitter opponents started to hope the time might come when they could strike. Planing for such a strike started surprisingly early, when the German army was still on the offensive in the Soviet Union and North Africa.

In the years following the "September Conspiracy," Hitler went from success to success. His regime swallowed the remainder of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 – although this was not ethnically German. He ordered the invasion of Poland just six months later, and a significantly larger army was crushed in just weeks. In April 1940 his armed forces walked into Denmark and Norway, overwhelming the ill-prepared defences of both neutral countries. Then in May/June 1940 Hitler pulled off the miraculous: his Third Reich conquered Belgium and Holland in just days, threw the British Expeditionary Force off the Continent in weeks, and forced the French to surrender in little more than a month of fighting. Hitler controlled the Continent of Europe from the Arctic Circle to the Mediterranean Sea. Never had a dictator been so popular, even adored, and there were many who latter joined the Resistance to Hitler – most notably Claus Graf Stauffenberg – who were so euphoric about the dictator's successes that they dismissed all his "minor" faults as irrelevant.

But not everyone in German shared this adulation of Hitler. A tiny minority of Germans retained their moral principles and their abhorrence of the immoral Nazi regime. They had no opportunity to take action against the oppressive dictatorship, however, as long as Hitler remained so successful and so popular.

Then in June 1941 came the invasion of the Soviet Union. Although this campaign was widely popular and initially went very well, by October the offensive started to bog down. By the start of December 1941, it had failed to reach either Moscow or St. Petersberg. On 6 December 1944, the Soviet Army opened a massive counter-offensive with fresh troops just brought in from the Urals and beyond. They exposed the extreme over-extension and exhaustion of the German Wehrmacht, rolling the German front hundreds of kilometers backwards. The retreating troops were confronted – often for the first time – with the atrocities committed behind their lines by the SS. The evidence of mass murders, the inhumane treatment of prisoners of war, and the military setback soon created a different psychological environment inside Germany. Those who had always opposed the Nazis, men like Ludwig Beck and Friedrich Olbricht, saw the first glimmer of hope that a coup against the Nazis might gain sufficient popular support to have a chance of success.

In the winter of 1941/1942 General Friedrich Olbricht, the highly decorated and audacious commander of the 24th Infantry Division, found himself trapped in a desk job in Berlin.

General Friedrich Olbricht in Poland 1939

General Friedrich Olbricht in Poland 1939He was now the Chief of the "General Army Office" (GAO) – a central office with responsibility for recruiting, organizing, arming, equipping, clothing, and otherwise providing for the replacements that were sent to the now voracious front. This position gave him command of no combat troops, but it did put him in a position to oversee practically everything the military was up to inside Germany. Olbricht convinced the Chief of Counter Intelligence, Admiral Canaris, to convince Hitler that there was a serious threat of revolt on the part of the millions of slave labourers imported to work in the Reich from all the occupied territories. Hitler in response ordered the Home Army (and hence Olbricht) to develop a General Staff plan for suppressing such an uprising. The plan was given the code name "Valkyrie."

Decades later, Axel von dem Bussche, a man who would later volunteer to become a suicide bomber in order to eliminate Hitler, spoke with enthusiasm and admiration of his first encounter with "Valkyrie."

Axel von dem Bussche in 1942

Axel von dem Bussche in 1942Bussche by early 1942 was already an opponent of Hitler. He was warned by a family friend (who was also an opponent of the Nazis) that he was to obey any orders he got from a "certain" General Olbricht. Bussche was a 1st Lieutenant at the time; Olbricht was a "three star" general. Since it was obvious to Bussche that he did not need specific instructions from a friend to follow the military orders of a general, he understood perfectly that the "orders" Olbricht was to give him were not normal military orders but rather something else again.

Then one day in early spring 1942, Bussche, then serving as adjutant in a replacement regiment stationed just outside of Berlin in Potsdam, got a call saying that General Olbricht was on his way to visit. Now, as Bussche worded it, the Chief of the GAO was as far above him as the "dear God is from earth." Bussche knew at once that this visit had nothing to do with official military duties – a suspicion reinforced after the general's arrival by a series of harmless questions and pleasant small talk that did not warrant the visit. But then Olbricht suggested that Bussche and he "stretch their legs." In the middle of an exercise field where no one could hear them, Olbricht started to "educate" Bussche about "Valkyrie."

"Valkyrie" was in Bussche's words: "A well organised plan of the Home Army that was to be used in the event that millions of forced labourers in Germany rose up in revolt." But Bussche understood perfectly well when Olbricht in his relaxed, Saxon inflection "explained" to Bussche: "Now Valkyrie, that is for when the forced labourers strike and we have to restore order, you understand?" And Bussche dutifully assured the general, "Jawohl, Herr General." So Olbricht continued, smiling, "And if it gets really bad, then we'll have to occupy the radio stations and the ministries in Berlin, you know what I mean?" "Jawohl, Herr General." And so the conversation continued until by the end, Bussche knew exactly what the General expected of him – without ever hearing a single word that could be construed as treason or even disloyalty.

Bussche would soon be transferred back to the Eastern Front and so the time frame for this meeting can be fixed without doubt to the late spring of 1942. It took place at a time when German arms were again on the advance, and the population had forgotten the winter of their discontent. It took place at a time when Stauffenberg was still convinced that Hitler could – and should – win the war. But Olbricht, Bussche, Beck and other individuals remained unswerving opponents of the Nazi regime, and although they were few and far between they now had a plan, a plan that could and would be employed to bring down the Nazis as soon as the necessary pre-conditions had been created.

The preconditions for the successful implementation of a coup based on Plan "Valkyrie" were two fold. First, there had to be a reasonable degree of disillusionment with the regime to make the population supportive of or at least neutral toward Hitler's removal from power. Second, but most important, Hitler had to be dead. It was no longer possible to contemplate the mere arrest of Hitler. First, the Valkyrie Orders could only be issued by the C-in-C of the Home Army if Hitler was "incapacitated," and, second, the army was not freed of its personal oath of "unconditional obedience" to Hitler unless he was no longer among the living. Thus Hitler's assassination was the first and essential step to a coup d'etat.

Responsibility for the assassination was assigned by Beck and the leadership of the evolving military conspiracy to the cell of anti-Nazi opponents centered in the military Counter Intelligence Department and led by Hans Oster. Oster's opposition to Hitler's policies also pre-dated the war. He had been in among the men in the September Conspiracy of 1938 that advocated Hitler's assassination even at this early date. His opposition to Hitler's aggression had been so great that he had taken the dramatic step of warning the Dutch of the impending German invasion in 1940. By 1942, Oster's hatred of Hitler and his regime was so intense that he was desperate to kill the dictator and happy to provide the means for doing so in the form of captured British plastic explosives.

But access to the increasingly cautious and reclusive dictator proved a greater challenge than anyone had initially anticipated. It was this, more than anything, that foiled repeated coup attempts over the next two years.

The German Resistance to Hitler was the subject of my PhD thesis. At the time I was the first Western academic granted access to key military archives and documents in what was then still "East Germany." In addition, I conducted interviews with over one hundred survivors of Nazi Germany, both supporters and opponents of the regime. The research culminated in a published dissertation and, later, an English-language biography of General Friederich Olbricht based on the dissertation. It also inspired me to write a novel about the German Resistance, which was recently re-released in ebook format under the title: "Traitors for the Sake of Humanity." Find out more and read reviews of "Traitors" at the publisher's website: Cross Seas Press.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

July 16, 2021

The First Coup Attempt - September 1938

It is often alleged that the German Resistance did not emerge until Germany was losing the war and the only goal of the conspirators was to avoid the "unconditional surrender" demand of the Allies. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The opposition to and rejection of Hitler on the part of leading members of the German Resistance usually pre-dated his appointment as chancellor and only grew more intense over time. Individuals such as Graf Stauffenberg who did not reject Hitler until after the start of the war were the exception rather than the rule.

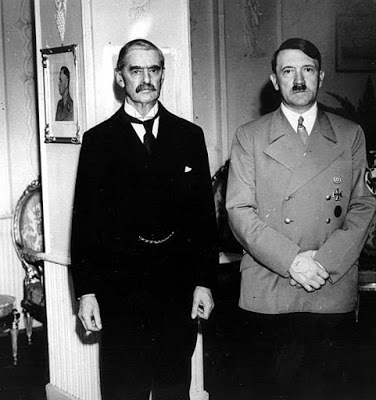

Their first military attempt by senior generals of the German army to remove Hitler from power was planned before the Second World War even started -- during the Sudeten Crisis of 1938.

The first military conspiracy against the Hitler and his criminally aggressive policies coalesced in 1938. Arguably, at no subsequent point in time did the conspiracy enjoy comparable chances of success. The military conspiracy of 1938 was headed by none other than the then Chief of the German General Staff at the time, Franz Halder. He was supported by many senior army generals including the later Field Marshal Erwin von Witzleben and General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel. The intellectual and moral guidance of this first conspiracy came, however, from the same man who would inspire and mentor all the latter coup attempts against Hitler: Generaloberst Ludwig Beck.

Generaloberst Ludwig Beck

Generaloberst Ludwig Beck Beck had succeeded General Adam as Chief of the General Staff on 1 October 1933. At the time of his appointment, he still hoped that Hitler's government would be a positive force for change. He hoped that Hitler would restore Germany to its rightful place as a European Great Power with an army commensurate to its legitimate defensive needs. Beck supported the policies of the Nazi government to dismantle the repressive measures of the Versailles Treaty, but at no time did he share Hitler's aggressive goals. Beck firmly believed that any attempt to obtain territory by force would lead to a two front war, which Germany would inevitably lose. Beck, furthermore, was horrified by the methods employed by the Nazis to suppress opposition domestically. Yet despite increasing unease over Hitler's domestic and international policies, Beck's crisis of conscience did not come until 1938.