Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 25

June 18, 2021

"The Battle of France is Over..."

On 18 June 1940, Winston Churchill told the House of Commons that the Battle of France was over, adding: "I expect the Battle of Britain is about to begin. ... The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned against us."

Churchill's famous words still have the power to mesmerize, particularly when coupled with Churchill's earlier statement "we will never surrender." Yet was it truly inevitable that Germany would attack Great Britain? Was the Battle of Britain unavoidable?

In fact, Britain did have an alternative in June 1940 -- and it was not surrender. Britain also had the option of a negotiated peace. Furthermore, this "solution" was the preferred option not only of the Germans but of a significant portion of the British political class, including members of Churchill's own cabinet. The most powerful voice favoring a peaceful settlement with Germany after the fall of France was none other than the British Foreign Minister, Lord Halifax.

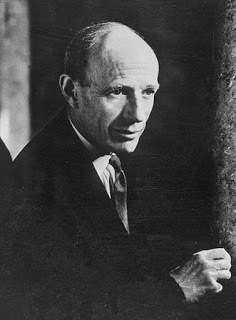

Edward Wood, later 1st Earl of Halifax, was a leading member of the Conservative Party in Great Britain, with a distinguished career in government during interwar years. He had been Viceroy of India from 1925 to 1931, where he had successfully negotiated a de-escalation of the growing conflict with Gandhi. He was influential in shaping the 1935 Government of India Act, and in the same year became Secretary of State for War, where he demonstrated a marked reluctance to face the possibility of war by resisting pressure for re-armament.

Despite Hitler's rise to power, Halifax was among the many in Britain, who saw German re-militarization of the Rhineland as a normalization of affairs on the Continent rather than an outrage. In November 1937 he was invited hunting by Goering and also met with Adolf Hitler. Although not an official spokesman of the British government at this time (the Foreign Minister was Anthony Eden), his close ties to the British government gave his words considerable weight. Evidently without consulting his Foreign or Prime Minister, Halifax conveyed to Germany's leaders the impression that Britain did not inherently object to adjustments to the map of Europe as drawn up at the Treaty of Versailles. Halifax acknowledged that German interests in "self-determination" had not been respected at the Peace Conference and that Germany had legitimate interests in Austria, Czechoslovakia and even Poland. However, he warned that any adjustments must be made by peaceful means.

Above Lord Halifax in 1947

Above Lord Halifax in 1947In February 1938, Halifax was appointed Foreign Secretary precisely because he had a more conciliatory attitude toward both Hitler and Mussolini, a position in line with that of the then Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. Hitler's annexation of Austria in March 1938, however, induced him to favor rearmament as well. Pragmatically, Halifax hoped for peaceful de-escalation of tension, but recognized the need to be prepared for war.

As the Munich Crisis approached, it was clear to both Halifax and Chamberlain that the British public (and certainly the Labour opposition) were vehemently opposed to war and an alternative had to be found. "Appeasement" appeared to be the best solution, defusing the immediate tensions and buying time for the democracies to re-arm. Halifax also recommended widening the government to include Churchill and Eden, but Chamberlain resisted.

By the end of 1938, Halifax increasingly advocated resisting further aggression on the part of Hitler and Mussolini, including a guarantee to Poland. He had no hesitation standing by that guarantee in September 1939, beyond wanting the French to commit at the same time. Throughout the first eight months of the war Halifax rejected negotiations with Hitler, first refusing to talk as long as German troops were still on Polish soil, and later saying (via Swedish intermediaries) that there could be no negotiation with Germany as long as Hitler was in power.

On May 8, despite narrowly surviving a vote of no-confidence in Parliament, Neville Chamberlain recognized it was time for him to step down and allow a new coalition government including Labour to be formed. The unanswered question, however, was who was to succeed him. The Labour leadership agreed to join a government, as long as it as not led by Chamberlain; they did not object to serving under Halifax, despite his position as a peer of the realm. King George VI favored Halifax as Chamberlain's replacement, and the Conservative Party as whole much preferred Halifax to Churchill, who was considered volatile, unpredictable and not entirely trustworthy. Yet in a meeting between Chamberlain, Churchill and Halifax on May 9, Halifax suggested that Churchill was the better man for the post of Prime Minister. Nevertheless, no decision had been taken by Chamberlain on who to recommend as his successor, when the Germans opened their offensive in the West, invading neutral Holland and Belgium.

That same evening, Chamberlain submitted his resignation to the king along with the recommendation that Winston Churchill be asked to form a government. Hours later, Churchill accepted the appointment, conscious both of how grave the situation was and of a sense of destiny. Yet while he proved capable of forming a coalition government, he remained an unpopular outsider, mistrusted by many in his own party and government and viewed with suspicious by the opposition as well. Meanwhile, Halifax remained Foreign Minister, and from this position he continued to command the loyalty and support of the majority. In consequence, his influence was far beyond what his official position would suggest.

Less than six weeks later, Belgium, Holland and France had all surrendered. The British Expeditionary force had lost 50,000 men, most of their guns and armor and all their transport. Although through the evacuation at Dunkirk the bulk of the troops had been safely brought home, the British army was no longer in a position to influence military developments on the Continent. With the surrender of France on June 22, the continent of Europe was completely under the domination of Germany and its allies Italy and the Soviet Union. To a practical man like Lord Halifax, it was time to revisit the option of negotiation with Hitler.

This was not because Halifax harbored illusions about Hitler being "decent" or trustworthy. By this point in time, Halifax appears to have genuinely detested Hitler. However, from Halifax's point of view, Britain had lost the war on the Continent -- not her army, thankfully, but the war. There was, he said bluntly, nothing to be gained by continuing the struggle when Britain had literally no means of doing so. It was impossible to economically strangle an entire continent, no matter how powerful one's navy is. It was impossible to wage war against a continental land power with ships alone. While Churchill spoke of fighting on the beaches, the landing grounds, the fields, streets, and hills, Halifax spoke of the duty of the British government to safeguard the nation's independence -- through negotiations.

When the Italian ambassador suggested that Mussolini might be able to broker a deal with Hitler, Halifax welcomed the offer and responded that Britain would be happy to listen to reasonable terms. After France surrendered on June 22, Halifax sent one of his closest associates to the Swedish Embassy with the message that Britain was still open to a reasonable settlement with Germany. He denied that Britain was committed to a fight to the death. Halifax's interest in a negotiated peace appears to have been motivated largely by the desire to prevent an air offensive against Britain that would cause loss of life and do inestimable damage to British industry. There is nothing dishonorable about the desire to save civilian lives and livelihoods.

Had Lord Halifax been tasked with leading the government at this point and had he advocated making peace with Hitler, he might have well enjoyed the passive, if not the active, support of the majority of the British public. Given the fact that Hitler himself had not anticipated and did not particularly want to continue the war against Britain (see: German Objectives in the Battle of Britain.), had Halifax rather than Churchill had headed the British government in June 1940 a negotiated settlement would almost certainly have been possible.

Nor should it be forgotten that it was not only Halifax and his supporters in the cabinet and Conservative party who wanted to negotiate with Hitler. British public opinion was also divided. There had been a far right wing party (British Union of Fascists) under Oswald Mosley, which was unabashedly anti-Semetic and pro-Nazi. Although banned at the start of the war, its members and sympathizers would certainly have supported a truce with Hitler. More importantly, as a result of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, the Communist Party was at this point also "pro-Hitler." Significantly, the Communists had gained in popularity after the start of the war, evidently attracting many committed pacifists, who opposed to war on principle. In short, an unknown percent of the British population may have actively wanted an alliance with Hitler. The greater part of the public, however, was shocked, confused and frightened by the unexpected, indeed unfathomable, collapse of France in just six weeks. Still in a state of shock after this catastrophe, the majority of the British would probably have accepted a negotiated settlement with Nazi Germany if their government had told them was in their best interests.

In other words, the Battle of Britain as not really inevitable -- except that Winston Churchill had with his own unshakable determination, confidence, and his gift with words succeeded in awakening a sleeping lion.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” depicts an England that is far from unanimous in its support for Churchill's policies and still sharply divided by class. It also shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagl... or watch a video teaser at:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnAoM...

June 11, 2021

The RAF Over Dunkirk

Many British soldiers felt the RAF failed to provide sufficient protection from the German Luftwaffe during the evacuation at Dunkirk. Despite Churchill's vigorous defense of the RAF's performance, British Army hostility toward the RAF for its alleged failure over Dunkirk continued to strain relations between the RAF and the army for years afterwards. With the benefit of hindsight, it is easier to see that Churchill’s assessment, while overly flamboyant, was closer to the mark.

On 21 May, just eleven days after launching their offensive against France, units of the German Wehrmacht reached the channel coast. By 24 May, Boulogne fell to the Germans and Calais was surrounded and besieged. The entire British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was trapped in a pocket centered at the town of Dunkirk on the Normandy coast. It was immediately apparent to the BEF’s Commanding General, John Viscount Gort, that only an evacuation to England could save his army. Expecting the German panzers to break through the weak perimeter defenses within a couple of days, the British war cabinet estimated that at most 45,000 men might be evacuated before the Germans overran the Allied defenses and ended the operation.

Fortunately for the British, on 23 May Generalfeldmarschall von Rundstedt ordered the panzers to stop pressing at the heels of the retreating British, French and Belgian forces pulling back towards Dunkirk. Some panzer divisions were down to 50% strength (more due to wear and tear on the vehicles than enemy action) and the German field marshal recognized the need to give the units time to rest and regroup before facing the main French army drawn up in defense of Paris. Furthermore, the terrain around Dunkirk was marked by marshes and canals, a combination viewed as unsuitable for armored vehicles. Hitler agreed with this tactical decision, while Goering eagerly offered to use air power to destroy the enemy troops crushed together in the Dunkirk pocket.

Between 24 and 26 May, the Allies forces used the lull in the ground fighting to establish a more robust, defensible perimeter around the port of Dunkirk. Thus, when the panzers received the order to advance again, they encountered organized and effective resistance. Furthermore, the German armored divisions were soon withdrawn from the fight for Dunkirk in order to engage in the assault on Paris. As a result, it would not be until June 5 that the German Wehrmacht seized the beaches of Dunkirk. By that date, an astonishing 338,226 Allied troops had been evacuated to safety in England.

The evacuation started slowly with the removal of just 7,700 men on 26 May, but by 27 May, the numbers had more than doubled to 17,300 men. On 28 May, although a similar number was evacuated, a flotilla of small ships arrived to aid in the operation. These had comparatively shallow draft, enabling them to move close enough to the beach for men to wade out to the boats rather than all having to file over the Eastern breakwater to board a ship moored at the end.

Thereafter, the numbers taken off daily increased significantly, peaking on 31 May. The daily number evacuated daily was approximately:

· 47,300 on 29 May;

· 53,800 on 30 May;

· 68,000 May 31;

· 64,400 June 1.

· 26,200 June 2

· 26,700 June 3

· 26,100 June 4

On the night of 2 June, the last of the British troops at Dunkirk were evacuated. Yet the operation did not end until another 75,000 French troops had also been transported to England. When the Wehrmacht broke through the defenses on June 5 and captured Dunkirk, only roughly 40,000 French troops remained to surrender.

Of those evacuated, 198,000 were British, 140,000 French, Belgian or Dutch. Not to be forgotten, however, were roughly 50,000 British troops who had not made it to the pocket at Dunkirk. Many had sacrificed themselves to make the evacuation at Dunkirk possible, fighting at Boulogne, Calais and the defenses around Dunkirk. Eleven thousand gave their lives, while the remainder became prisoners of war for the duration.

A total of 861 allies ships took part in the evacuation code named “Dynamo.” Of these, 693 were British. A cruiser, 39 destroyers, 36 minesweepers and 13 torpedo boats of the Royal Navy were joined by 49 warships from allied navies, but the vast majority of the ships that took part in the operation were not warships. In addition to 8 hospital ships, 45 troop/passenger ships, 113 trawlers, and numerous merchant ships, tugboats, ferries, pleasure boats and yachts assisted with the evacuation. While the larger ships accounted for the bulk of the troops rescued at Dunkirk (ca. 240,000); the small ships accounted for the remainder or nearly 100,000 men.

Royal Navy ships disembarking troops at Dover

Royal Navy ships disembarking troops at DoverThe evacuation was an astonishing and unexpected success, yet it came at a cost. In the course of Operation Dynamo, nine destroyers were sunk along with 200 smaller ships. Several of these ships sunk after taking troops aboard, resulting in the loss of thousands of lives — usually before the eyes of the troops still waiting to be rescued and the passengers and crews of other rescue vessels. Furthermore, starting 27 May, the troops awaiting their turn to board or already embarked were under frequent attack from the Luftwaffe. (On 25 and 26 May the Luftwaffe concentrated on bombing Calais, Lille and Amiens, and only thereafter started the offensive against Dunkirk.)

In the nine days from 27 May to 4 June, the Luftwaffe flew thousands of sorties against the trapped Allied troops, deploying over 300 bombers from two Kampfgeschwader protected by roughly 550 fighter escorts. In addition, it hammered the town of Dunkirk killing roughly 1,000 civilians, destroying the docks, and setting petrol tanks on fire that could not be put out because the water system had been shattered.

The Royal Air Force was tasked with preventing the Luftwaffe from slaughtering the Allied troops by establishing air superiority in the skies over Dunkirk. From Dowding downwards, no one was in doubt about what was at stake, and a maximum effort was made. When Operation Dynamo ended, 2,739 sorties had been flown in just nine days. Throughout, however, the RAF was fighting at a severe disadvantage.

First, it had just lost more than 300 front line fighters (Hurricanes) in the Battle of France. The squadrons that had fought in France were exhausted and no longer combat-ready. More importantly, only squadrons based in the Southeast of England, e.g. 11 Group, could be deployed over France because it was not possible to operate more squadrons from these airfields without overwhelming the command and control system. In short, the Air Officer Commanding 11 Group, Air Vice Marshal Sir Keith Park had just 32 squadrons and something close to 400 aircraft with which to stop the Luftwaffe.

Park was further handicapped by the lack of forward radar. This meant that, unlike during the Battle of Britain, he had no means of seeing the build-up and approach of German aircraft before they reached their targets. Without that information, it was not possible for Park to deploy his fighter aircraft economically by sending them on targeted interceptions. Instead, the RAF was forced to establish patrols, i.e. send aircraft to fly back and forth over airspace over Dunkirk and in the approaches to it. Pilots reported the frustration of flying patrol after patrol without ever encountering the enemy.

This was a very inefficient use of resources because the fighter aircraft of this period had limited fuel capacity. It took roughly 20 minutes to reach Dunkirk from Fighter Command airfields in Southwest England, and they needed another 20 minutes to return. That left the RAF fighters with fuel for a maximum of fifty minutes flying over Dunkirk and surroundings. If, however, German aircraft were spotted and engaged, the fuel consumption increased dramatically. In short, if the RAF fighters did what they were sent to do, the amount of time they could remain in French airspace fell to 30 minutes or less.

The combination of limited numbers of aircraft and limited patrol duration per aircraft meant for the RAF to patrol the air over Dunkirk continuously, the number of aircraft at anyone time would be no more than a handful. Initially, this was exactly what Park attempted to do; he deploying his fighters in flights of six or eight aircraft. The Luftwaffe, on the other hand, sent in bombers formations of 40 or more aircraft. As a result, that no matter how successful the six to eight RAF pilots were, most of the bombers still got passed them to drop their cargoes of high explosives on the troops and ships at Dunkirk.

Within days, Park changed his tactics, sending his fighters across in formations of two or three squadrons. This ensured that when they encountered the enemy, there were enough RAF fighters to effectively break-up a bomber formation and prevent it from delivering its cargo of death and destruction. However, the larger RAF formations could only be created by concentrating the limited forces Park had. This, in turn, meant that there were periods when, indeed, there was not one RAF aircraft in the skies over Dunkirk.

The perception of RAF absence was compounded by other factors. Many of the aerial interceptions and dog-fighting took place at altitudes invisible to the troops on the ground. This was not so much a function of absolute altitude as the fact that throughout the evacuation, the air over the beaches was dirty with the smoke from burning oil tanks and ships. Low cloud and fog was also reported on some days. Furthermore, much of the aerial fighting took place farther inland, as the RAF tried to intercept the bombers beforethey reached Dunkirk.

While the troops felt abandoned, the RAF pilots were flying five or six sorties a day — an extremely stressful burden that could not be sustained for long. Pilots were getting very little sleep, often woken at 3:30 am to be off at dawn and not released until after dark at 9 pm or later. First-hand accounts speak of eating little and having no time to bathe or shave. Some pilots also took to carrying pistols in their flying boats in case they were shot down behind enemy lines. The stress ate at each man differently, but there was no question in the eyes of the RAF leadership that the pilots were giving their best to the very limits of their endurance.

Although some sorties were futile, when the RAF did intercept the resulting clashes were bitter and deadly. In unlucky engagements, RAF squadrons could be gutted. Particularly damaging for morale was that in several recorded incidents, after being shot down in combat, RAF pilots were treated with disdain or anger by the troops they were trying to protect. In one case, an Army officer tried to prevent an RAF pilot from being taken off the beach so he could rejoin his squadron. The Royal Navy, fortunately, was more sympathetic and cooperative.

On the very first day of the operation, May 27, the RAF lost 14 aircraft and it lost another 13 on the following day. By the end of the evacuation, Fighter Command had lost 106 aircraft, including a number of precious Spitfires. Fifty-six pilots had been killed, and eight had bailed out over France and been taken prisoner. Coming on the heels of the losses in the Battle of France, these were significant numbers.

Officially, based on German statistics, the RAF succeeded in shooting down only marginally more aircraft than they had lost, namely 132. It must be remembered, however, that because the Germans were operating close to their bases, a large number of damaged German aircraft were repaired, rather than written off. These damaged aircraft do not appear in the German statistics. Yet in the battle over Dunkirk, damaged aircraft which were forced to turn back to base were almost as important as aircraft completely destroyed. RAF claims of destroying 390 German aircraft, while certainly inflated, may nevertheless give a better impression of the damage done to German effectiveness.

Ultimately, the success of Operation Dynamo speaks for the RAF. The Royal Navy deserves the lion’s share of the credit for organizing and implementing an improvised evacuation on this scale without a functioning harbor. The civilian volunteers that braved the mine-fields, the shore artillery and the Luftwaffe to make trip after trip in fragile, unarmed craft will always inspire awe, admiration and affection. Yet without doubt, RAF fighters played an important role in reducing the casualties on the beaches by hampering the Luftwaffe’s efforts to destroy the Allied troops from the air.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” opens in the Battle of France. It shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew or watch a video teaser at: Eagles Video Teaser

June 4, 2021

The RAF in the Battle of France 1939-1940

While the Battle of Britain represented the first time that the RAF and the Luftwaffe faced one another one-to-one, it was not the first encounter between the adversaries. RAF units had been involved in the Battle of France. While these had no chance of altering the outcome of that campaign, the British units and pilots engaged in the war on the Continent learned valuable lessons that contributed to the successful outcome of the Battle of Britain.

At the outbreak of WWII, the British almost immediately sent a “Expeditionary Force” to France. This included the Advanced Air Striking Force which consisted of ten squadrons of light bombers and four (later six) fighter squadrons. The bombers made up No 1 Group RAF Bomber Command, and this group was equipped entirely with Fairey Battles. Initially, the fighter squadrons deployed to France were Nos 1, 73, 85 and 87 squadrons, all Hurricane squadrons. However, in response to a French request for more fighter support, the RAF sent Nos 607 and 617 squadrons across to France on November 15. These auxiliary squadrons were at the time still equipped with bi-plane Gladiators, although they received their Hurricanes just as the German offensive opened in May 1940.

British strategy throughout this period called for both the bombers and fighters to serve in support of ground forces. Despite the appellation “Advanced Striking Force,” the RAF in France was a tactical air force intended to support the army. Thus, during the period of the so-called “Phony War,” the bombers were deployed primarily for reconnaissance and dropping leaflets in Germany, while the fighters were tasked with destroying German reconnaissance and weather aircraft that regularly crossed into French airspace.

For much of this period, there was little to do. The RAF fighters practiced intercepting their own bombers and they did routine patrols in the tradition of WWI — only rarely seeing, much less intercepting, the enemy. Now and again, however, there were brief, violent encounters with the Luftwaffe. Surprisingly, at this period the Luftwaffe was still sending its reconnaissance bombers over without noticeable escort. In consequence the illusion of doing very well was widespread. For example, on a single day, November 23, Nos 1 and 73 squadrons shot down six enemy bombers, five Dorniers 17 and one Heinkel 111. These were not inflated claims. The wrecks landed on French territory and the pilots went to see them and cut off a cross or swastika from the fuselage for the squadron mess. In one instance the pilot of a downed aircraft was royally entertained in the No 1 squadron’s mess.

Yet despite the apparent calm and the sense of readiness, the RAF learnt several valuable lessons in this pregnant calm before the storm. The commander of No 1 Squadron, “Bull” Halahan, convinced the RAF establishment of the advantage of painting the underside of aircraft sky blue, an innovation inspired by German standard operating procedures. Halahan was also the catalyst for an even more important change. When one pilot of No 1 squadron had a very narrow escape from being shot to death by the forward guns of a Dornier after overshooting following his own attack, Halahan decided that the Hurricanes needed armor plating behind the pilot’s seat. The request for such protection was denied by the Air Ministry on the grounds that the extra weight would alter the center of gravity and impair the aerodynamics of the aircraft. Halahan was not convinced. He took armor plating from a wrecked Battle, fitted it behind the seat of one of his squadron’s Hurricanes and sent one of his pilots back to London to perform aerobatics in the modified Hurricane before the Royal Aircraft Establishment. The performance must have been impressive because the Air Ministry caved in and ordered armor plating not only for No 1 Squadron but also made it standard equipment in all Hurricanes henceforth.

It was not a moment too soon. A notable increase in activity on the part of the Luftwaffe was recorded in March,1940. This led to the RAF’s first encounters with Me109s and Me110s. In the first exchange on 2 March 1940 both the RAF pilot (“Cobber” Kain of 73 Squadron) and Luftwaffe pilot (Werner Moelders) had to abandon their aircraft due to combat damage. On March 29, an engagement between a section of No 1 Squadron and three Me110s resulted in all three Me110s destroyed. The following assessment was entered in the squadron log: “As a result of this combat it may be stated that the Me110, although very fast and manoeuverable for a twin-engined aircraft, can easily be out manoeuvered by a Hurricane.” [Patrick Bishop, Fighter Boys: Saving Britain 1940, Harper Collins, 2003, 138.] The Germans, however, were provocatively sending larger and larger formations of bombers into French airspace — and they were now escorted by as many as forty Me109s.

Then on May 10, the German offensive in the West opened with a series of attacks on Allied airfields and other strategic, infrastructure targets. The Luftwaffe Order of Battle included 1,062 bombers, 356 ground attack aircraft (e.g. Stukas) and just short of 1,200 fighters of which roughly 1,000 were Me109 and 200 were Me110s. Facing them were the French Armee de la Air composed of 140 bombers, 518 single-engined fighters and 67 twin-engined fighters supported by 40 RAF Hurricanes and 20 RAF Gladiators. But the French figures are deceptive. In fact, only 36 French fighters were aircraft with an airspeed anywhere near that of their opponents; the rest were hopelessly obsolete.

One of France's 36 Dewoitine Fighters with a max. speed of 336 mph

One of France's 36 Dewoitine Fighters with a max. speed of 336 mph Even more disastrous was the absence of an early warning system. The French had been shown radar and the British fighter control system, but they disdained to follow the British example. In consequence, from the first day of the offensive to the surrender of France, there was no effective means of directing operations or guiding interceptions. There was also no cooperation or meaningful communication between the British and French air forces. All communications on the ground, whether between the British and the French, and within the British Advanced Striking Force were conducted over the civilian telephone lines. These were subject to German interdiction and not secure. Communication in the air was even worse, as the aircraft operating in France had very primitive radio telephone equipment with an effective range of just three miles from the airfield.

The Luftwaffe opened the campaign in the West with a text-book attempt to neutralize the air defenses of the enemy and secure air superiority over the battlefield. This meant that on the first day of the offensive, all the airfields from which RAF squadrons were operating were attacked. The RAF response was prompt and fierce. The pilots of No 1, 73, 85 and 87 squadron were in the air by 5 am and the day’s fighting did not finish until nine pm. Because the Germans had sent their bombers without fighter escorts, the RAF was able deliver a sharp rebuke. In 208 sorties, the RAF struck down 33 German aircraft for the loss of just seven Hurricanes destroyed, and eight damaged. More importantly, only one RAF pilot was killed, and three wounded.

But the Luftwaffe had the reserves to continue at the same pace; the RAF did not. In the following ten days, RAF pilots were asked to fly as many as five sorties a day, each lasting roughly an hour and a half. They did so while being forced to retreat almost daily to new, usually improvised, airfields, which nevertheless continued to be bombed and strafed regularly. Increasingly, RAF personnel were billeted with civilians, then sleeping in tents, later in abandoned barns and finally under the wings of their aircraft. Meals were erratic and sleep almost non-existent. If they weren’t flying, they were being bombed, strafed or moving to a new airfield.

All the while, the French government cried for more RAF squadrons. Their appeal fell on the sympathetic ears of the newly appointed British PM, Winston Churchill. Initially, squadrons stationed in southeast England were tasked to fly over and “help out.” Without early warning systems or functional command-and-control, however, these were doomed to arriving (often in the wrong place) to face utter chaos without a clue about what to do. Many ended up doing nothing or getting slaughtered without a single victory to show for it. Individual squadron replacements faced the same fate. Sending green pilots up to fight was more likely to result in the loss of a British than a German aircraft. Meanwhile, the RAF Fairey Battles were being systematically shot down as they attempted — usually without fighter escort — to stop the German panzer divisions pouring into France by destroying bridges or bombing them at choke points.

One of the RAF's Fairey Battles

On May 12, 501 Squadron was sent to France. On May 15, despite acknowledging that the Battle of France was lost, the French PM nevertheless requested of Churchill that ten additional fighter squadrons be sent across the channel. Although this request was denied, on the following day the Air Ministry decided that the fatigue both physical and mental sustained by the squadrons in France was not sustainable, and took the decision to send eight flights of fresh pilots over to relieve the exhausted veterans. The problem with that idea was that pilots without combat experience or understanding of the situation were cold meat for the Messerschitts. Meanwhile, on May 17 the RAF squadrons were retreating yet again, destroying any unserviceable aircraft on the ground as they pulled out. In some cases, the German bombers arrived while the last serviceable Hurricane was still struggling to get into the air.

The Air Ministry again tried sending UK-based squadrons across the channel to assist in the fighting. The idea was that three squadrons would fly over in the morning, do whatever fighting had to be done, and then get replaced by three other squadrons in the afternoon. All six squadrons theoretically remained stationed in the UK, but pilots were making forced landings and bailing out over France and then had to find their own way back. No 242 and 17 were two of the squadrons assigned this unenviable task. Furthermore, the issue of inexperience was the same with these squadrons, and the lack of communications prevented their coordinated and targeted deployment.

Inevitably, RAF losses mounted. While on May 10, only eight Hurricanes were destroyed and one pilot killed, on the 14th it was already 27 Hurricanes and 17 pilots killed. Two days later No 85 Squadron had six Hurricanes shot down in a single day, from which only one pilot walked away, the remaining five being killed or severely injured.

The following day, May 17, the Chief of Air Staff finally saw the light: British fighters were being destroyed at an alarming rate without the slightest hope of altering the military situation. The Germans were winning the war on the ground regardless of how good a fight the RAF put up in the air. The sacrifice of more British fighters and pilots could only weaken Britain’s capacity to defend itself when the time came. He announced in the war cabinet that it would be “criminal” to send more RAF squadrons to France. Two days later, Churchill also conceded defeat and ordered that no more RAF fighter squadrons were to be sent to France.

Slowly a withdrawal of the forces already there began. In many cases, individual pilots had to be left behind because they were in French hospitals. Around them, France was in a state of collapse with refugees clogging the roads, villages burning, panic and defeatism widespread. Many RAF pilots reported French fliers refusing to take to the air and French officers deserting their posts to rescue their families and possessions from the approaching Germans. First-hand accounts are also filled with horror stories of German bombing and strafing of civilians. The fact that German fighter aircraft also engaged in these atrocities did much to harden British attitudes toward the Luftwaffe at this crucial time.

Altogether, the RAF brought down 299 Luftwaffe aircraft in the course of this battle for the price of 208 Hurricanes lost in aerial combat. Not a bad score, although the claims were much higher, namely 599. Furthermore, another 176 Hurricanes were destroyed on the ground, often by the RAF ground crews to prevent them from falling into German hands. As a result, only 66 of the 450 fighters sent to France flew back to England.

More difficult to replace were the 56 pilots killed, 36 severely wounded and 18 taken prisoner. Many of these men were some of the best the RAF then had. Yet one casualty of the Battle of France has been all too often overlooked: RAF “Fighter Area Attacks”. These infamously inflexible tactics devised in the interwar years and so assiduously practiced right until the onslaught became an early casualty of the clash with reality. It was one casualty that did the RAF more good than harm.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel, following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew or watch a video teaser at: Eagles Video Teaser

May 28, 2021

Fighter Aircraft of the Battle of Britain - the Hurricane

While the Spitfire was the "glamor girl" of the RAF, the Hurricane was the unsung heroine of the Battle of Britain. Hurricanes destroyed more enemy aircraft than Spitfires and were flown by more RAF pilots on more squadrons. The Hurricane might not have captured the hearts of the nation nor intimidated the pilots of the Luftwaffe, but the men who flew her swore by her, and pilots familiar with both the Hurricane and Spitfire found much to praise about her.

The Hurricane was a less radical design than the Spitfire. It evolved from earlier generations of fighter aircraft, and was still partially a wood and canvass construction; although the cockpit, engine and wings were metal, the tail and rudder remained wood and canvas. Antiquated as this sounds, some aviation experts argue that it was actually an advantage because cannon shells that exploded on impact with the metal casing of a Spitfire, simply passed straight through the canvas without exploding or impairing the Hurricane's flying abilities. Furthermore, RAF riggers were familiar with this kind of construction and adept at making repairs -- something they often could not manage on the more sophisticated Spitfires. Indeed, Hurricanes could be packed in crates, shipped to distant theaters of war and re-assembled with equipment available in the field. Industrial manufacturing of the Hurricane was also easier and cheaper than for the Spitfire, requiring just 10,300 man-hours for the Hurricane compared to 15,200 man-hours to produce a Spitfire.

Unlike both the Spitfire and Me109, its wings were strong enough to support not only eight guns but the aircraft itself. Then meant that the retractable undercarriage could fold inwards from positions under the wings giving the aircraft a stable base which made it easy to taxi, land and take off. Its cockpit was designed to sit high on the distinctive "hunchback" giving the pilot unparalleled, all-round vision -- better than that of any other fighter in service at this time. Furthermore, as many pilots testified, it was an incredibly stable gun platform. In addition, the Hurricanes guns were better concentrated and could do greater damage to the well-armored bombers. These three factors help explain why Hurricanes accounted for 60% of all German aircraft shot down during the Battle of Britain.

RAF test pilots soon determined that the Hurricane was "simple and easy to fly and ha[d] no apparent vices." [McKinstry, Leo. Hurricane: Victor of the Battle of Britain. London: John Murray, 2010.] With a top speed of 340 mph it was slower than both the Me109 and the Spitfire. On the other hand, it had a faster rate of climb (2780 ft/min vs 2,600 ft/min) and a service ceiling just 500ft lower than the Spitfire and identical to the Me109. Significantly, it a tighter turning radius than any of its contemporaries. It could turn inside both the Spitfire and the Me109. All-in-all this aircraft was highly competitive and, as it proved, could well hold its own in the company of the Spitfire and Me109. It was also popular with the pilots who flew it -- and particularly the squadron and flight commanders who had go into combat with young pilots with very little flying experience. As already noted, it was a responsive aircraft that was easy to learn to fly and could be flown by effectively without many hours of practice. Because it could take direct hits without necessarily falling apart, young fledgling fighter pilots stood a better chance of surviving an unlucky encounter with the enemy than had they been flying a Spitfire or Me109. This is the reason Battle of Britain Ace Bob Doe, who flew both Hurricanes and Spitfires in the course of the war, said the Hurricane was the better machine for the "average" pilot, although an expert pilot could get more out of a Spitfire. (Photo below courtesy of Chris Goss.)

Although Stephen Bungay in his excellent analysis of the Battle of Britain [The Most Dangerous Enemy, Aurum Press, 2000, p.83] claimed the reserve fuel tank was insufficiently protected by the Linatex, a substance that was self-sealing and helped prevent fire, there is no evidence that fires occurred more frequently in Hurricanes than Spitfires or Me109s. Not one of the pilots who flew Hurricanes makes any mention of this and there was clearly no reluctance on the part of squadrons to fly Hurricanes, which should have been the case if the pilots thought they were more likely to be incinerated in a Hurricane than a Spitfire. Nor would a particularly dangerous aircraft have continued in production for so long nor found so many roles as was the case of the Hurricane. So any disadvantage caused by this arrangement must have been comparatively marginal.

Although Stephen Bungay in his excellent analysis of the Battle of Britain [The Most Dangerous Enemy, Aurum Press, 2000, p.83] claimed the reserve fuel tank was insufficiently protected by the Linatex, a substance that was self-sealing and helped prevent fire, there is no evidence that fires occurred more frequently in Hurricanes than Spitfires or Me109s. Not one of the pilots who flew Hurricanes makes any mention of this and there was clearly no reluctance on the part of squadrons to fly Hurricanes, which should have been the case if the pilots thought they were more likely to be incinerated in a Hurricane than a Spitfire. Nor would a particularly dangerous aircraft have continued in production for so long nor found so many roles as was the case of the Hurricane. So any disadvantage caused by this arrangement must have been comparatively marginal.Over 14,000 Hurricanes were produced altogether and the aircraft saw service in every theater of the war. Hurricanes served as night as well as day fighters. It was catapulted from Armed Merchant escorts, and flown from carrier decks. It was used as a close-support fighter-bomber and fitted with skis to serve in Russia. The Hurricane flew against the Luftwaffe in Norway, the Battle of France, over Dunkirk, in the Battle of Britain, and in North Africa -- where it was a particularly effective "tank buster." The RAF's highest scoring ace, Squadron Leader "Pat" Pattle, flew Hurricanes in defense of Greece against both the Italians and the Germans. Hurricanes also confronted the Imperial Japanese Air Force, seeing successful service in Burma, Ceylon, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies. Hurricanes were decisive in the defense of Malta, and also engaged on the Eastern Front. Hurricanes were initially sent to the Soviet Union to help protect convoys coming from the West to Murmansk and two RAF squadrons were detailed to operate them. During their deployment in August and September 1941, they accounted for 25% of the Luftwaffe aircraft shot. After the RAF withdrew, however, the Soviets made tried to mount heavier guns which made the Hurricane slower and less maneuverable, so the "Soviet" Hurricane cannot be compared to its British counterpart.

If there had never been a Spitfire, the Hurricane probably would have been the mechanical heroine of the Battle of Britain. The beauty and glamor of the Spitfire, however, cast a shadow over the image of the Hurricane. That shadow was darkened by the "Spitfire snobbery" of the Luftwaffe pilots (who frequently refused to admit they had fought -- and lost -- to Hurricanes) and the equally bigoted attitude of the Soviets, who mucked up a perfectly good fighter to no purpose at all. Yet, there can be no doubt that the Hurricane not only played a vital role in the Battle of Britain. Park's preferred tactic was to send Spitfire squadrons, with their faster aircraft, to divert and engage the Me109s and Hurricane squadrons, with their more stable gun-platforms and concentrated fire, to claw the bombers out of the sky. The standing orders to controllers to operate the different squadrons in this manner show the extent to which the Hurricane and Spitfire complimented each other during the Battle of Britain. Neither aircraft would have been as effective alone. In the remaining years of the war, both aircraft likewise went on to play different yet equally valuable roles in all theaters of war.

It was in part to give greater credit and visibility to this under-appreciated fighter that I chose to a Hurricane squadron as the focus of my novel Where Eagles Never Flew: A Battle of Britain Novel.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagl... or watch a video teaser at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnAoM...Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

May 21, 2021

Fighter Aircraft of the Battle of Britain - Spitfire

No aircraft is more closely identified with the Battle of Britain than the Supermarine Spitfire. No matter that more Hurricanes flew in the Battle or that the Spitfire made major contributions in other campaigns of the Second World War. The Spitfire, with its unique elliptical wings, is quite simply THE symbol of the RAF -- of "the Few" -- in the Battle of Britain.

If the Me109 descended from gliders, the Spitfire's forefathers were racing aircraft designed to win trophies for speed. So, it is perhaps not surprising that the Spitfire was the fastest of the four fighters that figured prominently in the Battle of Britain with a maximum speed of 360 mph -- or (a very marginal) three mph faster than the Me109 and ten mph faster than the Me110. Yet it was not the Spitfire's speed that made it the fighter most feared by the Luftwaffe. It was her sheer mastery of the air.

For those focused merely on the technical specifications, this statement is not comprehensible. The Spitfire could not dive as steeply as the Me109 -- her Merlin engine, which did not have fuel injection, cut out if she dived to steeply. Nor could she climb as rapidly as the Me109, at least at altitudes below 20,000 feet. Furthermore, the Me109 packed a harder punch in the form of two cannon rather than eight machine guns.

Yet the focus on the purely technical aspects of an aircraft -- at least in the 1940s -- is dangerously misleading. In the Second World War, aircraft had to be flown by humans, and it was the symbiosis between pilot and aircraft that accounted for combat (as opposed to test) performance.

Both the Me109 and the Me110 required considerable strength to handle at high speeds or altitude. The Me109 had a number of other bad habits such as right torque. The Spitfire, in contrast, could be controlled with the pilot's fingertips. She could be trimmed practically to fly herself. Pilots report coming to after losing consciousness in a dive or spin to find that the Spitfire had literally trimmed herself to fly straight an level. Pilots loved her -- unabashedly and uninhibitedly. Their confidence in her made them bolder. Their trust in her sustained morale even at the darkest moment. Their love of the Spitfire enabled them to perform on average at a higher level than had they been in a different aircraft.

While the Me109 has been compared to a vamp, the term most commonly used to describe the Spitfire was "a lady." The term was probably first coined by the Supermarine Test Pilot Jeffrey Quill, who allegedly remarked after his first flight in "her": "Here is a real lady." One of the RAF's highest scoring aces, "Sailor" Malan called her "a perfect lady." He claimed, "she had no vices. She was beautifully positive. You could dive till your eyes were popping out of your head ... [and] she would still answer to the touch." Battle of Britain Ace Bob Doe preferred to fly the Spitfire in shoes rather than flying boots in order to obtain a lighter and more direct control of the rudder -- rather like a rider on a young thoroughbred rather than an old hack. He claimed that the Spitfire "became part of you. It was an absolute joy."

The British public fell in love with the Spitfire too. Drives to collect scrap metal were called "Spitfire funds" -- not "Hurricane funds." Bungay in his book The Most Dangerous Enemy claims the Spitfire played "the role of the mythological role of a magical weapon, the equivalent of Achilles armour or the swords Excallibur or Nothing." [Aurum Press, 2000, 82]

Yet the greatest compliment to the Spitfire came from her opponents. The Luftwaffe respected the Spitfire but quite unjustly dismissed the Hurricane. This became known as "Spitfire snobbery." Luftwaffe pilots repeatedly made claims of shooting down -- or at least dogfighting with "Spitfires" -- when RAF records show there wasn't a Spitfire in the sky at the time and place designated. The Luftwaffe was fighting with and being shot down by Hurricanes -- they just weren't willing to admit it.

The later point is particularly glaring because far fewer RAF squadrons were equipped with Spitfires than Hurricanes during the Battle of Britain: 19 Spitfire Squadrons compared to 33 Hurricane squadrons. Furthermore, in the course of the Battle, Hurricanes accounted for more RAF "kills" at a rate of 3 for every 2 kills made by Spitfires. These kills, however, included bombers, while the Spitfires accounted for a higher proportion of the German fighters shot down.

Historically, the value of the Spitfire was demonstrated by her endurance. The Spitfire not only served in every theater of the war, it served in a variety of roles as 20 different "marks" or modifications of the Spitfire were designed. Spitfires flew from Royal Navy aircraft carriers, they were converted to fighter bombers, capable of carrying a 250 lb bombs under each wing and a 500 lb bomb under the fuselage. They were extremely successful and valuable as high altitude photo-reconnaissance aircraft.

Later models of the Spitfire were capable of speeds of 440 mph and could fly at 40,000 feet. They successfully shot down V1 rockets. Spitfires were not retired from service with the RAF until the introduction of jet aircraft in the early 1950s.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagl... or watch a video teaser at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnAoM...Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

May 14, 2021

Fighter Aircraft of the Battle of Britain - Me 109

The German fighter that caused the most damage to the RAF during the Battle of Britain was not the heavy "Destroyer/Zerstoerer" but the smaller Me109. It has been compared to a vampire, and it proved such a good design that, with modifications, it remained in service throughout the Second World War. Altogether, nearly 34,000 Me109s were built, more than any other World War Two fighter.

The Me109 was the brain-child of Willi Messerschmitt, who had started his career in aviation as a glider designer. The Me109 inherited from Messerschmitt's glider designs wings with superior lift and an overall design that was streamlined and light.

This design, however, created other problems. The wings were too delicate to carry eight machine guns, ammunition boxes or support the weight of the aircraft when on the ground. As a result a series of work-arounds had to be developed. Two machine guns fired from beside the engine cowling and two cannons were fitted on the wings rather than eight machine guns. (Latter versions removed guns from the wings altogether and had cannons fired through the spinner of the propeller. The ammunition boxes were located in the fuselage and the guns fed by belts that stretched to the wingtips and back. But the problem was the very narrow undercarriage was never really solved and caused many accidents while taxiing and landing throughout the war. Furthermore, because the canopy was hinged and opened to the side, it could not be left open during take-off and landing; this meant the pilot could not simply lean out to look around the long nose (that blocked forward vision); he had to weave back and forth slightly to see where he was going.

In the air, the Me109 fitted with a 1,000 hp engine was without doubt a superb fighter. At the duel between prototypes competing for the Luftwaffe contract in 1935, the Me109 preformed a spectacular series of spins and a power dives that blasted the competition right out of the game. It was easy to handle, and in the hands of an expert was extraordinarily maneuverable and agile. Fitted with fuel-injection engines, the Me109 had a maximum speed of 357 mph at 12,300 feet and a service ceiling of 36,000 feet -- substantially higher than that of its opponents in the Battle of Britain. Americans who test flew the Me109 before the start of the war (including Charles Lindbergh) considered it superior to any fighter aircraft the U.S. had at the time.

Yet it had drawbacks in the air too. The canopy was made up of several panels fit into a metal frame and that created bars that blocked the pilot's vision -- that could be fatal in a dogfight. The Me109 could not be trimmed to fly straight and level; it required constant right ruder to counter the torque of the propeller. Perhaps the most serious drawback was the canopy that opened sideways and could not be readily released during an emergency. Without doubt many German pilots died because of this feature.

Although much is usually made of the turning radius of a fighter, in the Battle of Britain, the Me109, the Hurricane and the Spitfire had technical radii so similar that it was the capabilities of pilot more than those aircraft that were the deciding factor in a dogfight. Pilots were more likely to black-out in a tight turn than for the aircraft to stall. Experienced pilots with a better feel for their aircraft were able to push their machines closer to the latter's limit, while inexperienced pilots often stalled, lost consciousness or were unnecessarily afraid of tearing the wings off. Nevertheless, technically both the Spitfire (by a very small margin) the Hurricane (by a considerably greater margin) could out-turn the Me109, so in the hands of a skilled and confident pilot, this was a British advantage.

When all was said and done, the Me109s accounted for 3/4 of the 1,023 RAF fighters shot down in the Battle of Britain, Me110s, bombers and accidents accounting for the rest. Thus, on a fighter-to-fighter basis, the Me109 was the clear victor of the battle , shooting down 770 Spitfire and Hurricanes for losses of just 650 of their own number. Yet the RAF fighters combined shot down 223 Me110s, and more importantly 1,014 bombers for a total of 1,887 German aircraft. The Me109 alone, at least not in the numbers deployed, could not win the Battle of Britain.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The leading German characters are pilots and women auxiliaries serving with and Me109 Gruppe in Northern France. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagl... or see an video teaser at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnAoM...

Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

May 6, 2021

Fighter Aircraft of the Battle of Britain - Me110

At the start of the Battle of Britain, the German Luftwaffe thought they had the perfect weapon. It had been especially designed as a "destroyer" and its role was to be an offensive fighter. It had range, speed, forward and rearward firing guns, and it had already proved its value in the fight against Poland. It was the Me110:

The Me110 had been designed by Messerschmitt to specifications from 1934. It had a speed of 350 mph at 22,000 feet, roughly the same top speed of a Spitfire and marginally faster than the Hurricane. It was armed with two forward-firing cannon and four forward-firing machine guns as well as an additional machine gun that faced backwards and was manned by a dedicated gunner. Serving an aggressive dictator, the Luftwaffe confidently ordered enough of these "Destroyers" (Zerstörer) to outfit a third of their fighter squadrons.

When war came in September 1939, the Luftwaffe's fighter force during the invasion of Poland was composed almost exclusively of the Destroyers, while the smaller Me109s were left in the Reich for air defense purposes. The Destroyers' job in this campaign was two-fold -- to destroy the enemy's air force and to protect the Luftwaffe's bombers. In the first role, the Destoryer rapidly proved to be a formidable bomber-killer. It was fast enough to catch or even over-take contemporary bombers -- including RAF Wellingtons that ventured too far into German airspace, while its fire power was sufficient to destroy them. As an escort fighter, it likewise appeared to do good work because the Polish Air Force was largely destroyed on the ground and the Destroyers did not have to contend with defending fighters.

During the offensive in the West in 1940, the situation was largely repeated. The majority of enemy aircraft were caught on the ground and there were never enough RAF fighters around to effectively challenge the dominance of the Luftwaffe. Victories in individuals sometimes went to one side or the other. There was no evidence of clear advantage for one fighter or another -- especially since no Spitfires had been deployed to France.

Even during the evacuation at Dunkirk, the weaknesses of the Me110 did not become apparent. While the British mounted a massive defense of the airspace over the beaches of Dunkirk, they had only 200 fighters to the Luftwaffe's 550 and to deploy over Dunkirk they ate up a lot of fuel crossing the Channel, which left them little time for dog-fighting. Furthermore, at no time in the Battle of Britain was the need to destroy the bombers before they reached their targets more apparent; the RAF concentrated on bringing down bombers, not engaging fighters unless absolutely necessary.

Not until the so-called "Kanalkampf" of July 1940 did the first inklings of problems emerge. When the Luftwaffe started to probe British defenses, it soon discovered that Hurricanes and the Spitfires in the hands of skilled and motivated pilots did not have much difficulty shooting down the vaunted "Destroyers." The problem was that while the Destroyers were fast, they did not accelerate rapidly. To make matters worse, they could not turn tightly and, like most multi-engined aircraft, they didn't particularly like rolling. What this meant was that any competently flown Hurricane or Spitfire could easily evade the massive firing-power fixed facing forward and maneuver onto the tail of the Me110 -- where they equally easily made a mockery of the Me110's rearward-firing guns. Rather than destroying much, the Destroyers were rapidly becoming the prey.

To stay alive, the Me110s rapidly devised the tactic of forming a defensive circle that slowly lumbered across the sky in one direction or another. The idea was that the Me110's could use their forward guns and cannon to protect the tail of the aircraft ahead of it. It worked up to a point, however, Spitfires and Hurricanes were so nimble they could turn inside these circles, shooting up one Destroyer after another. That, or they merrily swooped down from above or up from below to take pot-shots at the flying merry-go-rounds robbed of all offensive abilities.

It was increasingly becoming clear that far from protecting the bombers (except in the sense that they may have distracted some RAF fighters from the real targets, the bombers), the Me110 was a itself vulnerable in an engagement with modern single-engine fighters. Yet the Luftwaffe believed it's long range would enable play a role in attacks launched from Norway against the North of England, which was presumed to be denuded of fighter defense. They weren't, and August 15 saw a such high casualties among Me110s that Goering gave orders they had to be protected -- i.e. the "super" fighter needed a fighter escort. Altogether, the Luftwaffe lost 223 Me110s during the Battle of Britain -- essentially their entire Order of Battle at the opening. While replacements meant entire units were not wiped out, aircraft strength was in some cases reduced to nearly 50%.

Yet it would be wrong to dismiss the Me110s as worthless. On the contrary, they proved highly effective -- in a different roles. The Me110 demonstrated its worth as a low-level, precision bomber even during the Battle of Britain itself, when as part of the Test Wing 210, it was responsible for some of the most devastating attacks on airfields or radar installations. However, it was as a night-fighter that the Me110 found its true niche.

The Me100 was equipped for instrument flying and its cockpit was large enough to accommodate a radar operator, making it suitable for night fighting. More importantly, however, it was strong enough to be outfitted with twin, upward-firing 20 millimeter cannons. So equipped, the Me110s found it easy to slip in undetected below the RAF's night bomber streams, maneuver to a point where the obliquely upward-slanting guns were directed at the wing tanks of the bomber and fire away. Because they did not use tracer, the RAF didn't know the Me110 was there unless or until they were hit. One experienced Luftwaffe pilot destroyed seven Lancasters in this fashion in a single night -- and then quit because he was tired of killing. It has been estimated that kill-to-loss ratio of the Me110 vs RAF bombers was 30:1.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagl... or watch a video teaser at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnAoM...Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

April 30, 2021

The Fighter Aircraft of the Battle of Britain: Part I - Introduction

Before the Battle of Britain, it was widely believed that there was no effective defense against air assault, and that "the bomber would always get through." Most air forces in the inter-war years focused their attention and budgets on building large bomber fleets with which to cudgel the enemy. The assumption was that the nation that could deliver the most high-explosive on the homeland of its enemy would win the war by breaking enemy civilian morale. The Luftwaffe, notably, took a somewhat different approach, focusing on medium range bombers designed more to support of ground forces than conduct strategic bombing. In both doctrines, however, fighter aircraft played only a secondary role. The Luftwaffe's experience in Spain, Poland, Holland and France seemed to validate their strategy. The Luftwaffe had generally overwhelmed enemy air defenses by surprise attacks that eliminated enemy air forces while they were still on the ground. This paved the way for the Luftwaffe bomber force to support ground operations by destroying tactical targets selected by the army such as bridges, marshalling yards, rail-junctions and the like. In addition, the Luftwaffe engaged in widespread attacks on enemy cities -- a strategy that struck terror into the hearts of many.

Before the Battle of Britain, it was widely believed that there was no effective defense against air assault, and that "the bomber would always get through." Most air forces in the inter-war years focused their attention and budgets on building large bomber fleets with which to cudgel the enemy. The assumption was that the nation that could deliver the most high-explosive on the homeland of its enemy would win the war by breaking enemy civilian morale. The Luftwaffe, notably, took a somewhat different approach, focusing on medium range bombers designed more to support of ground forces than conduct strategic bombing. In both doctrines, however, fighter aircraft played only a secondary role. The Luftwaffe's experience in Spain, Poland, Holland and France seemed to validate their strategy. The Luftwaffe had generally overwhelmed enemy air defenses by surprise attacks that eliminated enemy air forces while they were still on the ground. This paved the way for the Luftwaffe bomber force to support ground operations by destroying tactical targets selected by the army such as bridges, marshalling yards, rail-junctions and the like. In addition, the Luftwaffe engaged in widespread attacks on enemy cities -- a strategy that struck terror into the hearts of many.

The Battle of Britain, however, presented the Luftwaffe with a new challenge. The Luftwaffe no longer had the element of surprise on its side. Furthermore, the army would not engage until after the Luftwaffe had successfully cleared the skies of British aircraft. Last but not least, Britain was surrounded by water. Nevertheless, the Luftwaffe opened the Battle of Britain supremely confident of its ability to rapidly subdue the Royal Air Force and establish the air superiority necessary for an invasion. The Nazi leadership furthermore believed that the Luftwaffe's ability to strike at targets in Britain would cause sufficient terror -- or at least consternation -- to bring the British to the negotiating table.

Up to this point, the primary tool in the Luftwaffe's arsenal for destroying enemy air forces had been the Stuka dive bomber. Stukas had wrecked havoc in the campaigns in Spain, Poland and France -- because they had repeatedly caught enemy aircraft while they were still on the ground. However, very early in the Battle of Britain, during the Kanalkampf phase, it became apparent that the Stuka's were themselves extremely vulnerable to RAF fighter attacks unless they were defended by Luftwaffe fighters. By the second phase of the Battle (Eagle Day and afterwards) it became clear that

all

the Luftwaffe's bombers were vulnerable without fighter escort. (A lesson the USAAF had to learn all over again in 1942-1943.) By mid-August, the Luftwaffe had also learned that their twin-engined fighter, the Me110, was likewise no match for the RAF's single-seater fighters. German success in the Battle of Britain increasingly depended on the smaller, single-engine Me109.

Up to this point, the primary tool in the Luftwaffe's arsenal for destroying enemy air forces had been the Stuka dive bomber. Stukas had wrecked havoc in the campaigns in Spain, Poland and France -- because they had repeatedly caught enemy aircraft while they were still on the ground. However, very early in the Battle of Britain, during the Kanalkampf phase, it became apparent that the Stuka's were themselves extremely vulnerable to RAF fighter attacks unless they were defended by Luftwaffe fighters. By the second phase of the Battle (Eagle Day and afterwards) it became clear that

all

the Luftwaffe's bombers were vulnerable without fighter escort. (A lesson the USAAF had to learn all over again in 1942-1943.) By mid-August, the Luftwaffe had also learned that their twin-engined fighter, the Me110, was likewise no match for the RAF's single-seater fighters. German success in the Battle of Britain increasingly depended on the smaller, single-engine Me109.From the British perspective, the bombers were the primary targets. Only the bombers could deliver the destruction that would 1) destroy their ability to keep fighting, 2) damage the economy, and 3) possibly shatter civilian morale. But the British very rapidly learned that they first had to peel away the fighter escorts before they could do much damage to the bombers.

As a result, the air-to-air combat in the form of fighter dogfights played a vital -- though not the exclusive role sometimes implied in popular imagery -- in the Battle of Britain. Understanding the characteristics of the four main fighters is therefore valuable to an understanding of the Battle. With the exception of the Me110, which was patently inferior to the other three, the fighters were very well-matched. There are countless instances of both British fighters defeating Me109s, but also of Me109s besting both British machines. Equally telling, all three aircraft remained operational through-out the war. This series will start by looking next week at the Me110. At the opening of the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe had great expectations for this fighter, believing it could prove decisive. It is worthwhile considering its characteristics and weaknesses before looking at the three "stars."

As a result, the air-to-air combat in the form of fighter dogfights played a vital -- though not the exclusive role sometimes implied in popular imagery -- in the Battle of Britain. Understanding the characteristics of the four main fighters is therefore valuable to an understanding of the Battle. With the exception of the Me110, which was patently inferior to the other three, the fighters were very well-matched. There are countless instances of both British fighters defeating Me109s, but also of Me109s besting both British machines. Equally telling, all three aircraft remained operational through-out the war. This series will start by looking next week at the Me110. At the opening of the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe had great expectations for this fighter, believing it could prove decisive. It is worthwhile considering its characteristics and weaknesses before looking at the three "stars."

The following week, May 14, I'll look at the Me109. This fighter was produced in larger numbers than any other German fighter. Although the FW190 and, obviously, the later jet fighters such as the Me262 were generally viewed as better, the Me109 remained the work-horse of the Luftwaffe's fighter wing because it was ultimately good-enough -- as the men of Bomber Command and the USAAF can attest.

May 21st, I'll turn to the Spitfire. This iconic aircraft won fame as soon as it appeared, and the Luftwaffe pilots were so awed by it that they often claimed to be fighting Spitfires even when they were facing Hurricanes. The Spitfire became the symbol of Britain's defiance and victory in the Battle of Britain and remained the RAF's most beloved fighter throughout the war. It underwent multiple modifications and at various times was viewed as inferior or superior to the German fighters it faced, but it proved its worth in six long years of war.

May 21st, I'll turn to the Spitfire. This iconic aircraft won fame as soon as it appeared, and the Luftwaffe pilots were so awed by it that they often claimed to be fighting Spitfires even when they were facing Hurricanes. The Spitfire became the symbol of Britain's defiance and victory in the Battle of Britain and remained the RAF's most beloved fighter throughout the war. It underwent multiple modifications and at various times was viewed as inferior or superior to the German fighters it faced, but it proved its worth in six long years of war.

The Hurricane, which I'll examine in more depth on May 28, is probably the most maligned (or at least misunderstood) of the Battle of Britain fighters and is frequently dismissed as 'inferior.' This is utterly unjustified by its performance. It brought down more German aircraft in the Battle of Britain than did the Spitfire (though there are various reasons for that), and although withdrawn from service in Great Britain itself, it was successfully deployed to other theaters of war. In the course of the war, it fulfilled a variety of roles, all of which it performed credibly. Indeed, it can be argued that the Hawker Hurricane was one of the most most versatile aircraft of the Second World War.

The Hurricane, which I'll examine in more depth on May 28, is probably the most maligned (or at least misunderstood) of the Battle of Britain fighters and is frequently dismissed as 'inferior.' This is utterly unjustified by its performance. It brought down more German aircraft in the Battle of Britain than did the Spitfire (though there are various reasons for that), and although withdrawn from service in Great Britain itself, it was successfully deployed to other theaters of war. In the course of the war, it fulfilled a variety of roles, all of which it performed credibly. Indeed, it can be argued that the Hawker Hurricane was one of the most most versatile aircraft of the Second World War.

“Where Eagles Never Flew” shows the Battle of Britain from both sides of the Channel by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. Find out more about “Where Eagles Never Flew” at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagl... or watch a video teaser at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnAoM...

Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

April 23, 2021

The Battle of Britain Through German Eyes - The Assault on London

As the first week of September drew to a close, the Luftwaffe believed it was winning the war of attrition with the RAF but at a higher cost and a slower pace than anticipated. Crews were tired, tempers on edge and the time for an invasion was running out. Hitler extended the deadline for the invasion to September 21 to give the Luftwaffe more time to “soften up” English defenses, but he also expressed doubts about the Luftwaffe’s successes. Goering scented political trouble. He wanted an alternative to “more of the same.” An attack on London seemed just the thing.

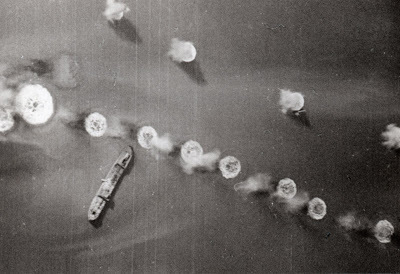

German bombers over London - Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

German bombers over London - Courtesy of the Imperial War MuseumThe decision to switch the focus of the air offensive from RAF Fighter Command to the British capital was not made flippantly. The commander of Luftflotte 3, Generalfeldmarshall Hugo Sperrle opposed the move vehemently. He believed the German fighters were greatly exaggerating their claims (whether intentionally or unintentionally) and he doubted that Fighter Command on was on its last legs. He believed that the assaults on the RAF itself should remain the primary objective of the air offensive.

His counterpart in Luftflotte 2, Generalfeldmarshall Albert Kesselring, wasn’t convinced the RAF was broken either, but he noted that (unlike the Dutch, Belgians, and French) the RAF was not allowing itself to be destroyed on the ground. That is, he was fully cognizant of the fact that the Luftwaffe had caught very few RAF fighter aircraft on the ground and drew the incorrect conclusion that the Luftwaffe’s attacks on RAF fighter stations were not terribly effective. He noted further that the RAF possessed a plenitude of airfields beyond the range of his fighters and — since he could not afford to send in unescorted bombers — that meant these fields were de facto immune to attack. Kesselring believed that the RAF would defend itself from destruction by pulling their aircraft back to stations beyond the range of the Luftwaffe.

In other words, German ignorance of the vital role of the Sector Operations Rooms at the Sector Control Stations misled the Luftwaffe into underestimating the effect their concentrated attacks on key (albeit not all) RAF airfields had had. This miscalculation combined with the over-estimation of the losses the RAF suffered in the air, led Kesselring to the conclusion that the Luftwaffe needed to concentrate on a target that the RAF would be forced to defend in the air. The British capital seemed ideal for this purpose.

Goering, however, was probably swayed not by Kesselring’s military arguments so much as by political considerations. He had bragged that the British could not bomb Berlin — but they had. Although the physical damage was nominal, the damage to his reputation was more substantial. “People” were making jokes about him. Far more serious, however, was the fact that Jodl had long advocated an all-out attack on London. The Battle of Britain dragged out with still no British pleas for peace negotiations, Jodl sounded more and more convincing. Goering was at risk of losing Hitler’s trust, and in an authoritarian dictatorship the consequences of losing the dictator’s trust were dire.

The bottom line was that Hitler wanted an attack on London. His patience with the stubborn British — or at least Churchill’s government — had worn out. He might have once admired the British Empire, but he detested being flouted. The fact that an attack on London would contribute little to creating the conditions for an invasion did not interest him. He had never been all that keen on the invasion anyway. There was more than one way to skin a cat. If the invasion was called off, Hitler presumed he could starve Britain with his U-boats while pulverizing her cities from the air. Why waste ground troops he needed to subdue the Soviet Union?