Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 23

November 12, 2021

Characters - Part II of a Ten-Part Reflection on Creative Writing

For me, characters more than plot define a book and determine its success. As a reader, if I really like a character, the plot can be simple, but if I don't, the best plot in the world cannot capture my interest. As a novelist, I write two kinds of historical fiction, biographical novels and non-biographical novels requiring different types of characters. The biographical novels are based on the lives of historical figures and the major characters are indeed real, historical figures. The non-biographical novels are novels set in a known/documented historical context but using fictional characters to describe and explore the historical era/event. In short, my characters fall into two categories: historical figures and invented people. Yet they are not really as different as one may think.

First, is important to recognize that any character in a novel, even if based rigidly upon the historical record, is to a degree fictional. Unless we are lucky enough to have memoirs, diaries or letters left behind by a historical character, most of what we know about people in the past is what others have written about them. We are far more likely to know what they did than why they did it.

First, is important to recognize that any character in a novel, even if based rigidly upon the historical record, is to a degree fictional. Unless we are lucky enough to have memoirs, diaries or letters left behind by a historical character, most of what we know about people in the past is what others have written about them. We are far more likely to know what they did than why they did it. A novelist writing about a famous figure from the past usually interprets and expands upon the historical record. A novelist will fill in gaps in the historical record by interpolating between two known data points. A novelist usually attempts to explain behavior by imagining possible motives and to make a character more comprehensible by suggesting emotional states-of-mind. A novelist will certainly invent dialogue and may also invent secondary characters to interact with the historical figure in order to make that character more understandable.

While I presume that most of the above is widely known, it may come as a surprise to many readers that I view some of fictional characters as no less — indeed arguably more — “real” than the historical ones. The reason for this is that some of my fictional characters — individuals not found in any historical record — are so vivid and so complete when they form in my imagination that I question that I could have created them.

Yes, there are characters that I create and manipulate at will, but there are others that direct me on what they did and said and thought and felt. I cannot do with them as I please. I cannot make them behave in ways they do not want, nor can I put words into their mouths. On the contrary, they tend to want to take over a novel and push it in the direction they want. They certainly provide much of the key dialogue and the plot.

Working with them is always a delight. For one thing they are full of surprises. They greatly enrich my stories because they have more wit and humor than I. An example of this kind of character is Robin Priestman in Where Eagles Never Flew.

Another advantage of these characters is that the writing comes easily and is almost always print-ready — but only those scenes seen from their point of view, of course. Since my novels are complex and I prefer portraying historical events from a variety of perspectives because I believe this enriches our understanding of the subject, these scenes written by characters still have to be embedded in the wider context of the novel and that can be hard work when dealing with strong personalities.

Another problem is that I cannot ignore them. This past year I had wrapped up, completed and edited two novellas that I planned to release under the title Grounded Eagles. I had already turned to my next project, a novel about the Berlin Airlift. I was very happy with this project, going back to research I had done for my non-fiction book The Blockade Breakers. Indeed, I’d written more than 100 pages of this new work with Kit Moran disrupted everything.

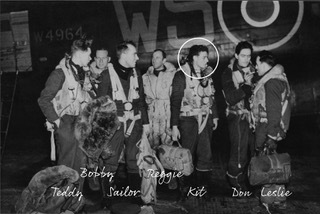

Moran demanded that I include his story about being posted for Lack of Moral Fibre in November 1943 in my (I thought finished) Grounded Eagles. I could not continue my work on Bridge to Berlin. Nor could I release Grounded Eagles on schedule. I needed to set everything aside, write Moran’s story, find appropriate materials for a cover, go back to my editor etc. etc.

Moran demanded that I include his story about being posted for Lack of Moral Fibre in November 1943 in my (I thought finished) Grounded Eagles. I could not continue my work on Bridge to Berlin. Nor could I release Grounded Eagles on schedule. I needed to set everything aside, write Moran’s story, find appropriate materials for a cover, go back to my editor etc. etc. And as if that weren’t enough, having completed Lack of Moral Fibre both as a stand-alone ebook and a component part of Grounded Eagles, Moran insisted that I write about what happened to him after the incident in November 1943. Fortunately, he’s a delightful young man and I don’t mind spending time with him and his Georgina, but he has been disruptive of all my planning!

For more information about both books see: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

And: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

November 5, 2021

Inspiration - Part I of a Ten-Part Reflection on Creative Writing

As the year winds down and I take stock of my accomplishments, I find myself reflecting more and more on my principal activity: creative writing. I've decided to share some of my insights about my own, personal process and goals in a ten-part series. Today Is start with the genesis of a book: the inspiration.

Above: my husband and I at the Mena House Hotel, Giza, Egypt. Somehow the pyramids seemed like an appropriate image for reflecting on the source of inspiration.

Above: my husband and I at the Mena House Hotel, Giza, Egypt. Somehow the pyramids seemed like an appropriate image for reflecting on the source of inspiration.Since I write historical fiction, the fundamental idea or trigger for a book is almost always an event in history that excites my interest. I usually stumble upon these catalysts quite by accident — e.g. when on holiday somewhere new, or reading about something else. I cannot approach a new novel rationally as I would non-fiction project, by evaluating what topics would be most relevant or popular or valuable. Nor can a second person suggest a topic to me. Unless I am personally inspired to write about an event/era/incident, it is an utter waste of time to try.

Once I start a novel, however, I draw as much upon my own experience with and understanding of mankind as I do upon the historical record and scholarly sources. I novel requires credible and attractive characters, and no matter how they are dressed, where or when they “lived,” they need to behave in ways consistent with human nature as I perceive it today.

One of the best examples of this is probably my depiction of Leonidas of Sparta as a youth going through the infamous agoge. Most readers will be familiar with the horror depicted in the film “300” or more lurid — but popular — allegations of mindless brutality resulting in many deaths and a complete disregard for literacy much less music, art or other subjects. Yet the popular view of the agogeis not supported by contemporary sources. Most legends about the agogedate from the Roman period, more than six hundred years after Leonidas lived and after two major changes in regime.

Having examined the evidence for the agoge in the era in which Leonidas attended, I found that it was viewed by such Ancient Greek intellectuals as Chilon, Socrates and Plato as admirable and progressive. (Would Socrates have approved of children not learning to read? Would Plato have wanted his second most important citizens to be mindless brutes?) I also learned that Sparta in the age of Leonidas was famous for its singing and dancing. (Is that consistent with a society that flogged its youth to death?) I learned that philosophers visited and taught in Sparta. (Taught illiterate youth who were out fighting with the wolves to survive?) I could go on, but you probably see my point.

I threw out the sensationalist (possibly propaganda) reports written by non-Spartans about an institution that existed more than 600 years after Leonidas’ death along with all the modern fantasies constructed on those ancient sources and started creating a Spartan agoge based on contemporary or near contemporary sources. (My newest source was Xenophon, 430-350 BC.)

Furthermore, I knew while Spartan youth were expected to be soldiers-only for ten years, after that, while still subject to military service, they were also expected to be bureaucrats managing a wealthy and diverse state. (See: https://spartareconsidered.blogspot.com/2017/10/public-administration-spartas-hidden.html) Full Spartan citizens needed many skills starting with basic literacy and numeracy and Sparta’s soldiers need to know more than how to march and kill.

Combining this knowledge, I hypothesized an educational system consistent with what was known about Sparta but based more on educational systems around the world today. E.g. an age-based curriculum designed to give children and youth the skills they would need as adults in the world in which they lived. This in turn enabled me to create a Leonidas with whom most readers can readily identify -- as would not be the case if he was simply a victim of sadistic cruelty for 14 years. The result is a novel, A Boy of the Agoge which has won wide praise for its authenticity.

Find out more at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/boy-o...

October 29, 2021

An Inconvenient War - The RAF Strategic Bombing Offensive

The Battle of Britain was a glamorous defensive battle fought by a "few" against seemingly overwhelming odds and it has -- rightly -- captured the hearts and imaginations of generations. Yet, it was a short, three-month interlude in a six-year-long war of bitter attrition. Churchill was correct when he said the fate of civilization hung in the balance during the Battle of Britain. Yet while the Battle of Britain prevented Nazi victory, it did not assure Allied victory. British success in the Battle of Britain was only the first necessary precondition for a continued Allied struggle against Nazi tyranny in Europe. From the withdrawal of the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk in June 1940 until the Normandy invasions in June 1944, Britain's only means for striking at Germany's military and industrial capacity was through a bomber offensive.

Strategic bombing, as bombing offensives are more commonly called, is not popular with anyone anymore -- if it ever was. Strategic bombing isn't pretty. It isn't glamorous. It isn't heroic. Bombing offensives are cruel. They kill the innocent as well as the guilty. They destroy priceless and irreplaceable historical and cultural monuments. In a post-war world where the urgency of victory had dissipated, the ugly face of strategic bombing was not something anyone wanted to remember anymore, and so it was largely relegated to the realm of "necessary evils" best swept under the carpet.

That natural tendency not to dwell on the unpleasant was compounded by the results of the Strategic Bombing Survey. This survey, commissioned by the U.S. Secretary of War to assess the damage done by the Allied strategic bombing, was carried out by a panel of civilian experts that produced a report 208 volumes long with over 200 supporting documents. Released in October 1945, it pointed to startling failures that shattered wartime faith in the efficacy of bombing. For example, the Strategic Bombing Survey found that German aircraft production more than doubled from 15,596 aircraft of all types in 1942 (before the start of strategic bombing) to 39,807 aircraft in 1944. Likewise, tank production peaked in 1944, despite the bombing offensive, and -- particularly disappointing to the USAAF -- there was no evidence that the repeated and costly attacks on the German ball bearing industry had any impact on the war at all. The Strategic Bombing Survey, furthermore, assessed the results of the entire Allied air offensive, the U.S. as well as the British bombing, and was particularly dismissive of night bombing, the RAF's contribution, because of it's limited accuracy.

Such results were quickly seized upon by opponents of strategic bombing and are the most familiar facts known about the survey to this day. The influential economist John Kenneth Galbraith concluded that strategic bombing had been virtually worthless and called it a strategic blunder. He suggested that it had stimulated the German economy and stiffened German resolve to fight rather than the reverse. Such an assessment poured oil on the flames of moral outrage over the civilian and cultural casualties of bombing. Strategic bombing was increasingly viewed as mindless terror.

If one accepts this conclusion, then the losses sustained by the Allied Air Forces were unconscionable. The RAF alone lost roughly 55,000 men, or almost exactly 100 times the losses in the Battle of Britain. (Although to keep things in perspective, one should remember that the British lost 125,000 men at the Battle of the Somme alone.) While hardly anyone blames the pawns of this war, the aircrew, they were nevertheless increasingly portrayed as victims rather than heroes, as the dunces of the diabolical and heartless political and military leadership.

Yet the conclusions of the Strategic Bombing Survey were much broader and more complex than the simple facts noted above suggest. The Survey, undertaken so shortly after the war, had grave issues with verifying data and there is strong reason to believe, for example, that many Nazi "production figures" were fantastical book-keeping exercises fabricated to cover-up reality from the Nazi leadership. Furthermore, beside the noted failures, the survey recorded significant success. For example, the Allied bombing offensive was extremely effective in closing down Germany's synthetic oil and petroleum production, contributing materially to the collapse of the Wehrmacht's mobility. More dramatically -- if late in the war -- submarine production was completely disrupted. Altogether, the Survey concludes that strategic bombing contributed materially to Allied victory and shortened the land offensive.

Impossible to calculate, yet critical to any conclusions about the efficacy of Allied strategic bombing in WWII, is an answer to the following question: What would German industrial and military capacity have been without the Allied strategic bombing campaign? Would a successful invasion of the Continent and Germany have been possible without strategic bombing in the previous four years?

We know that the bulk of German fighters were deployed to the defensive of the Reich because of the bombing offensive. What if, instead, they had been on the fronts providing the air cover so urgently needed by the Wehrmacht? Or, put another way, what if the Allies had not had air superiority over the beaches of Normandy? What if the 2 million men manning anti-aircraft batteries in the Reich had been available to fight on the Eastern Front? What if the 8,8 flak guns had been deployed as tank killers instead of clustered around Germany's industrial cities to bring down bombers?

Moreover, in addition to it impact on economic and military capacity, strategic bombing was intended to both damage enemy and bolster domestic morale. The impact on German morale has been particularly controversial. Clearly, the Germans did not rise up in rebellion, but such an expectation is naive. However, there is evidence to suggest that the population of industrial centers was significantly less loyal to the regime than the rest of the German population. This was in part due to a tradition of Socialism in the urban centers, but also do to the effects of bombing. Leaving aside the political component, German (including contemporary Nazi) sources stress that the continuous disruptions to water, electricity, transportation, and sleep undermined worker morale and efficiency -- but in a way that is difficult to quantify.

On the other hand, after the loss of roughly 52,000 British lives in the German bombing offensive against Britain, the British public expected retribution. That may not sound very noble or altruistic, but it was a political reality that could not be ignored. As a result, the RAF's bombing offensive was popular throughout the war and aircrew stood in high regard with the British public.

Last but not least, for four long years the bombing offensive against Germany was Britain's sole means of taking the war to the enemy. By doing so, Britain demonstrated her determination to defeat Hitler. The bombing offensive was also critical in fending off strident Soviet demands for a premature "second front."

Ultimately, regardless of the utility of their actions in retrospect, the young men who volunteered to fly in this extremely hazardous and costly campaign deserve recognition and regard. Roughly 8,000 aircrew from Bomber Command lost their lives in training, before embarking on a single operational sortie. Although survival rates steadily increased in the course of the war, with losses per operation falling from 4.1% in 1942 to less than 1% in 1945, nevertheless, on average the chances of surviving a tour of 30 operations averaged just 29%. The men who took those risks again and again in an attempt -- however vain -- to weaken Nazi Germany should be remembered with respect.

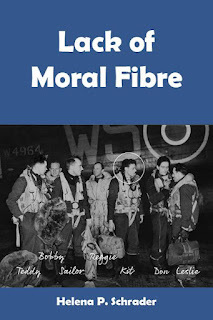

Lack of Moral Fibre and my work-in-progress, Lancaster Skipper, are dedicated to depicting and honoring the contributions of RAF Bomber Command aircrew to the war. You can find out more about Lack of Moral Fibre at: https://crossseaspress.com/lack-of-mo....

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

October 22, 2021

Lack of Moral Fibre -- A Reassessment

The term “Lack of Moral Fibre” was introduced into RAF vocabulary in April 1940 and was ‘designed to stigmatize aircrew who refused to fly without a medical reason.’ [1] While it is now most commonly associated with ‘shell-shocked’ bomber crews, in fact aircrew from all commands could be and were categorized as LMF in the course of the war. Humiliating as the concept was, the myths about the treatment of LMF were more terrifying than the facts.

The RAF entered the war confident that its volunteer aircrew, all viewed as the finest human material available, would not suffer from any crisis in morale. Yet already by January 1940, attrition rates of over 50% in Bomber Command, triggered a crisis in confidence among commanders and crews. At the same time, Coastal Command morale was undermined by unreliable engines and unarmed aircraft that proved extremely vulnerable to Luftwaffe attack.

On March 21, 1940 the Air Member for Personnel met with senior RAF commanders to develop a procedure for dealing with flying personnel who refused to ‘face operational risks.’ The concern of these senior officers was that the refusal to fly would become more widespread, debilitating the RAF. The RAF’s dilemma was that flying was ‘voluntary,’ hence the refusal to fly was not technically a breach of the military code.

The RAF needed an alternative means of punishing and deterring refusals to fly on the part of trained aircrew. Furthermore, because of the on-going crisis, the procedures for dealing with the problem were required immediately. There was no time for a lengthy investigation of the causes or research into best practices for treatment. So LMF procedures were introduced.

Over time the polices on LMF were modified significantly and increasingly discredited. Yet it is telling that at the height of the Battle of Britain, AVM Sir Keith Park strongly advocated the policy, emphasizing that aircrew deemed LMF should ‘be removed immediately from the precincts of the squadron or station.’

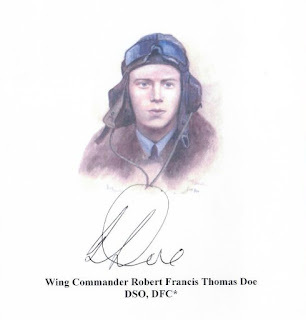

Furthermore, while nowadays LMF is most commonly associated with bomber crews, the statistics show a that only one third of LMF cases came from Bomber Command. Surprisingly, fully a third came from Training Command, while both Coastal and Fighter Commands also had their share of LMF cases. Fighter Ace Air Commodore Al Deere describes in detail a case of a pilot from No 54 Squadron who avoided combat and was later ejected from the squadron for being “yellow.”Fighter Ace Wing Commander Bob Doe records another incident towards the end of the Battle of Battle of Britain in which a Squadron Leader conspicuously avoided combat, but because the Squadron Leader was from a different squadron, no action was taken.

For the men who continued flying operations, the fate of those ‘expeditiously’ posted away from a squadron for LMF was largely shrouded in mystery. Legends about LMF abound. During the war itself, it was widely believed that aircrew found LMF were humiliated, demoted, court-martialed, and dishonorably discharged. There were rumors of former aircrew being transferred to the infantry, sent to work in the mines, and forced to do demeaning tasks. Aircrew expected to have their records and discharge papers stamped “LMF” or “W” (for Waverer) with implications for their post-war employment opportunities.

Long before the war was over, however, the very concept of LMF was harshly criticized and increasingly discredited. In the post-war era, popular perceptions conflated LMF with “shell shock” in the First World War and with the more modern concept/diagnosis of Post Traumatic Shock Syndrome PTSS. In literature — from Len Deighton’s Bomber to Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 — aircrew were increasingly depicted as victims of a cruel war machine making excessive and senseless demands upon the helpless airmen. Doubts about the overall efficacy of strategic bombing, horror stories depicting the effects of terror bombing on civilians, and general pacifism in the post-war era have all contributed to these cliches.

In reality, LMF was a more complex and nuanced issue. First, although there are documented instances of aircrew being humiliated in a parade during which flying and rank badges were stripped off, such public ceremonies were extremely rare. The vast majority of references to such public spectacles are second hand; that is, the witness heard about such procedures at a differentstation or squadron.

Historical analysis of the records, on the other hand, show almost no evidence of widespread humiliation. Furthermore, over the course of the war, less than one percent of aircrew were posted LMF, and of these the vast majority were partially or completely rehabilitated. Only a tiny fraction were actually designated LMF or the equivalent. (The term used for describing aircrew deemed cowardly varied over time, including the terms “waverer” and “lack of confidence.”) Furthermore, the process for determining whether aircrew were LMF or not was far more humane than the myths of immediate and public humiliation suggest.

While the decision to remove a member of aircrew from a unit was an executive decision, applied when member of aircrew had “lost the confidence of his commanding officer,” the subsequent treatment was largely medical/psychiatric. Thus, while a Squadron Leader or Station Commander was authorized — and expected! — to remove any officer or airman who endangered the lives or undermined the morale of others by his attitude or behavior, a man found LMF at squadron level was not automatically treated as such by the RAF medical establishment.

On the contrary, RAF medical personnel were at pains to point out that LMF was not a medical diagnosis at all! It was a term invented by senior RAF commanders in order to deal with a phenomenon they observed — and feared. In consequence, once a man had been posted away from his active unit, he found himself inside the medical establishment that employed Not Yet Diagnosed Nervous (NYDN) centers to examine and to a lesser extent treat individuals who had “lost the confidence of their commanding officers.”

The medical and psychiatric officers at the NYDN centers (of which there were no less than 12) were at pains to understand the causes of any breakdown. They did not assume the men sent to them were inherently malingerers or cowards. On the contrary, as a result of their work they made a major contribution to understanding — and helping the RAF leadership to understand — the causes for a beak-down in morale. These included not only inadequate periods of rest, but irresponsible leadership, lack of confidence in aircraft, and issues of group cohesion and integration. As a result of their interviews with air crew that had been posted LMF, for example, the medical professionals were able to convince Bombing Command to reduce the number of missions per tour and to exempt aircrew on second tours from the LMF procedures altogether.

Meanwhile, more than 30% of the aircrew referred to NYDNs returned to full operational flying (35% in 1942 and 32% in 1943-1945), another 5-7% returned to limited flying duties, and between 55% and 60% were assigned to ground duties. Less than 2% were completely discharged.

In addition, there is considerable circumstantial evidence that at the unit level, pains were taken to avoid the stigma of “LMF.” No one understood the stresses of combat better than those who were subjected to them. It was the comrades and commanders, who were themselves flying operationally, who recognized both the symptoms and understood the consequences of flying stress. These men largely sympathized with those who were seen to have done their part. Certainly, men on a second tour of operations were treated substantially differently — at both operational units and at NYDNs — than men still in training or at the start of their first tour.

Fighter Ace Air Commodore Al Deere, DSO, OBE, DFC and Bar noted: “The question ‘when does a man lack the moral courage for battle?’ poses a tricky problem and one that has never been satisfactorily solved. There are so many intangibles; if he funks once, will he next time? How many men in similar circumstances would react in exactly the same way? And so on. There can be no definite yardstick, each case must be judged on its merits as each set of circumstances will differ.” (Photo below courtesy of Chris Goss)

While conditions varied over time, from station to station, and from commander to commander, on the whole RAF flying personnel did not seek to punish or humiliate a comrade who in the past had pulled his weight. Instead, informal means of dealing with cases of men who “got the twitch” — other than posting them LFM — were practiced. Precisely because such practices were “informal” they are almost impossible to quantify, yet the specific cases documented are almost certainly only the tip of the iceberg.

This is not to say that LMF policies did not have a powerful impact on RAF culture. The fact that so many aircrew knew about LMF and had heard rumors of humiliating practices for dealing with LMF demonstrates that the possibility of being designated LMF was an ominous reality to aircrews. Because of the draconian punishment expected based on the myths surrounding LMF, the threat of being designated LMF acted as a deterrent to willful or casual malingering. Tragically, the threat of humiliation may also have pushed some men to keep flying when they had already passed their breaking point, leading to errors, accidents, and loss of life.

Deere noted: “In my first tour [during the height of the Battle of Britain], despite the many narrow escapes I was always confident that I could come through alright. In contrast, throughout [a later tour], although it was far less hectic, there was always uppermost in my mind the thought that I would be killed….I don’t think I was any more frightened than previously, and it can only be that I had returned to operations too soon after so many nerve-racking experiences…. The result was a lack of confidence, not so much in my ability to meet the enemy on equal terms, but in myself (or my luck).”He admitted that by the time he was relieved of his command and sent on a publicity tour to the United States he was, in fact, overdue for another rest.

During the Second World War, psychiatric professionals increasingly came to recognize that “courage was akin to a bank account. Each action reduced a man’s reserves and because rest periods never fully replenished all that was spent, eventually all would run into deficit. To punish or shame an individual who had exhausted his courage over an extended period of combat was increasingly regarded as unethical and detrimental to the general military culture.”

Yet we should not forget that behind the notion of LMF was the deeply embedded belief that courage was the ultimate manly virtue and that a man who lacked courage was inferior to the man who had it. RAF aircrew were all volunteers. They were viewed and treated as an elite. Membership in any elite is always dependent on the fulfillment of certain criteria. Since the age of the Iliad courage has been — and remains — the most fundamental characteristic expected of military elites around the world. And it probably always will be.

Lack of Moral Fibre examines this problem in a fictional case study. In late November 1943, Flight Engineer Christopher “Kit” Moran, DFM, refuses to fly to Berlin on what should have been the seventh “op” of his second tour of duty. His superiors declare him “lacking in moral fibre” and he is sent to a mysterious NYDN center. Here, psychiatrist Wing Commander Dr. Grace must determine if he has had a mental breakdown requiring psychiatric treatment — or if he deserves humiliation and disciplinary action for cowardice.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!Lack of Moral Fibre is one of three tales bundled together in Grounded Eagles. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-e...

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

[1] Edgar Jones, “LMF: The Use of Psychiatric Stigma in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War,” The Journal of Military history 70 (April 2006). 439

[i]Jones, 446.

Deere, Alan C. Nine Lives. Crecy Publishing. 1959. 111-119.

Doe, Bob. Fighter Pilot. CCB Aviation Books, 2004. 44.

Deere, 112-113.

Deere, 232.

Jones, 456.October 15, 2021

Press on Rewardless: A Closer Look at RAF Groundcrew in WWII

It has become commonplace to note that in the Battle of Britain "the Few"were supported by "the Many." As a rule of thumb, it took nine men on the ground to support one man in the air and this was not just true in Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain, it was true throughout the war in Bomber Command as well. That figure includes cooks, stewards and batmen, medical personnel, the clerks looking after supplies and records, the intelligence and control room staff, armorers and communications specialists and more. All personnel on an RAF station contributed in some way to victory by doing their jobs. Yet, just behind the pilots in importance were -- in my opinion -- the ground crews that maintained the aircraft under extremely difficult circumstances. The "erks" in RAF jargon.

It was no accident that the RAF was able to rely upon superb ground support throughout the Second World War. From its inception as a separate service, the RAF had broken with the army and navy and consciously set out to establish an entirely new institution with an ethos all its own. The founder of the RAF talked of creating and encouraging an "air spirit." [Quoted in Patrick Bishop. Fighter Boys. HarperCollins, 2003, 28] Yet while that might have been interpreted as a focus on flying alone, Trenchard recognized from first hand experience the need for qualified ground crew. At the same time that he established the Royal Air Force College a Cranwell to train officers and research centers for aircraft development, he established an apprentice program to attract technically minded young men to serve on the ground in his fledgling service.

Apprentices received their education, room and board free, but committed to twelve years of service. They were sent to a training institute at Halton Park in Hertfordshire where they lived under RAF discipline. From the day the training program opened it was popular. The applicants came from the lower middle and upper working classes and it was seen as a huge opportunity to enter the glamorous world of aviation. Getting in was not easy. Not only were there thousands of applicants for the limited number of spaces (five thousand for the 300 spaces in 1921), but applicants also had to pass an entry exam including English, mathematics and science. Although youths as young as 15 were accepted into the program, few youth who had left school at 14 could pass the exam and it was generally the children of families affluent enough to keep their boys in school to 16 who filled the ranks.

Training lasted three years and in some ways the graduates of Halton were as well educated as the graduates of Cranwell. This inevitably led to a blurring of the distinctions between the ranks, reducing the sense of divide between officers and other ranks, something Trenchard appears to have consciously sought. Bishop writes: "Trenchard was as proud of Halton as he was of Cranwell. He was aware that by engineering a new class of educated other ranks, the first in British military history, he was doing something radical, almost revolutionary." [Bishop, 34]

Furthermore, the RAF actively encouraged ambition by offering cadet scholarships to Cranwell for the three best apprentices each year. Another training scheme allowed flying training for outstanding ground crew, who thereby gained sergeant's stripes regardless of what trade they fulfilled on the ground and when the war started, roughly one quarter of the RAF's pilots were regular sergeant pilots trained through this scheme. In 1944, Trenchard told parliament that the apprentice program had contributed significantly to social mobility and meritocracy within the RAF.

Under the circumstances and given the fact that many pilots came up from the ranks themselves, it is hardly surprising that the relations between pilots and ground crews were on the whole excellent. Furthermore, in the Battle of Britain, and indeed throughout the war, individual crews looked after individual aircraft and so specific pilots. The ground crews identified strongly with their unit – and ‘their’ pilots.

In the Battle of Britain, the bombing of the airfields started in mid-August, the ground crews were themselves under attack, suffering casualties and working under deplorable conditions – often without hot food, dry beds, adequate sleep and no leave. The ground crews never failed their squadrons. Aircraft were turned around – rearmed, re-fuelled, and thoroughly checked – in just minutes.

Indeed, throughout the war, RAF ground crews served "their" aircraft and aircrews with dedication. They worked long hours, often through the night or in rain or snow, to ensure aircraft were not only serviceable but as safe to fly as possible.

A Rose in November: A WWII Love Story for the Not-so-Young features a ground crew chief.

Not all lovers are young. Rhys Jenkins is “Chiefy” of a Spitfire squadron in late 1940, a full-time job in itself, but he is also a widower with two teenage children in need of his attention. Hattie FitzSimmons has devoted her life to the Salvation Army ever since WWI ended her hopes for a husband and family of her own. They are no longer young when they find each other, but they both feel things are ‘right’ — until Rhys discovers that Hattie has been hiding something from him.

A Rose in November is one of three tales bundled in Grounded Eagles. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-e...

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

October 8, 2021

The Most Exclusive Club in the World -- The Guinea Pig Club

Speaking of it after the war, the celebrated plastic surgeon Dr. McIndoe claimed: “It has been described as the most exclusive Club in the world, but the entrance fee is something most men would not care to pay and the conditions of membership are arduous in the extreme.”

The Guinea Pig Club

One of the greatest hazards in flying a in WWII was the risk of fire. The combination of high-octane aviation fuel and incendiary bullets meant that many aircrew burned to death in their aircraft before they could escape. Yet some managed to escape the flames and live — often with first degree burns covering their faces, hands and other parts of their bodies. Crash-landings also sometime resulted in complete disfigurement. In an age when plastic surgery was still in its infancy, reconstructing faces was largely an experimental process. So, the pilots treated by the pioneering and talented New Zealand plastic surgeon Archibald McIndoe called themselves the “Guinea Pigs.”

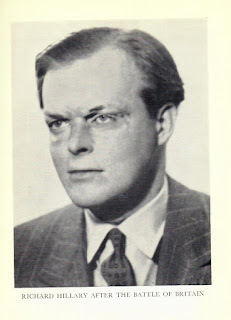

Over 600 patients benefited from the then experimental surgery techniques employed by Dr. McIndoe. By the time Dr. McIndoe’s Ward at the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead closed in 1948, 80% of the patients had been aircrew from Bomber Command and most of the rest aircrew from Fighter Command. Only a handful of patients had been Royal Navy or Army victims of burn or other accidents requiring plastic surgery. It was Battle of Britain pilot Geoffrey Page started the Guinea Pig Club; membership was restricted to those who received Dr McIndoe’s medical care and the staff that worked in his ward. Another Battle of Britain pilot, Richard Hillary, made McIndoe’s work famous in his wartime classic, The Last Enemy. (Below a photo of Hillary before being shot down in flames on September 3, 1940.)

McIndoe's patients had all sustained such severe injuries as to require a series of operations to reconstruct facial features and replace skin. Skin grafts were taken from other parts of the patient’s body and sewn in place to create eyebrows, eyelids, lips, and ears. Hands also sometimes had to be reconstructed. In one case, Dr. McIndoe created fingers from the bones of the back of the hand. In nearly all cases, skin grafts were required for the hands as well as the face.

Throughout the slow reconstruction process, the risk of infection was great. Furthermore, some grafts simply wouldn’t take, meaning that the operation had to be repeated until it worked. Because operations had to be spaced out to allow the body time to recover between interventions, patients spent many months and sometimes several years in treatment.

In addition to experimenting with medical techniques to treat burns and conduct plastic surgery, McIndoe pioneered methods to treat the psychological impact of such disfiguring injuries. While all severe wounds have a psychological impact on a patient, the loss of one’s face was particularly shattering because human identity is strongly tied to what we see in the mirror.

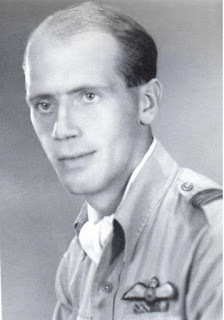

Battle of Britain ace Bob Doe's face was crushed into his gun-sight during a crash landing, tearing out one eye and ripping off his nose as well as "redesigning" his upper jaw and the right-hand side of his face (as Doe worded it in his memoir). Bob Doe remembered:

I suffered every time I looked in a mirror and was sure that I had been quite handsome. But now, to me, I was unrecognisable. I have found that to some extent, your face creates your character and your character creates your face. Either way, I had changed, and I did not know what I was. [Bob Doe. Fighter Pilot. CCB Aviation Books, 2006, 54.]

Below Doe before the plastic surgery.

Geoffrey Page describes the following incident:

One of the prettiest girls I’d seen in my life came into the room to help [the matron] with the dressings. Attired in the cool, colourful uniform of a V.A.D. Red Cross nurse, she personified the wounded warrior’s vision of the ideal angel of mercy. Standing beside the dressing trolley assisting the professional nurse, she was unable to hide the expression of horror and loathing that registered on her lovely face at the sight of my scorched flesh. [Geoffrey Page. Shot Down in Flames. Grub Street, 1999, 86.]

Page requested a mirror and was denied it by the matron. She told him bluntly:

“You will be allowed to look in a mirror, Pilot Officer Page, when I see fit to permit it and not before.” [Geoffrey Page, 87.]

After the nurse had left, Page with great difficulty managed to drag himself out of bed and stagger to washbasin beside his bed above which hung a mirror. He writes:

“Tottering in front of the mirror, I squeezed the moisture out of my eyes and surveyed the image in front of me. The shock of the swollen face three times the normal size was almost too great to comprehend…. [Geoffrey Page, 88.]

Below Page before the plastic surgery.

Clearly, McIndoe’s patients were facing exceptional psychological stress — and most of them were hardly out of their teens. He responded by encouraging an informal atmosphere that including barrels of pale ale in the ward. Between treatments, the patients were sent to convalescent homes or allowed to stay with family and friends. They were encouraged to wear their own clothes or service uniform rather than hospital attire, and they were encouraged to be social. That meant going to the pub, the theatre, flicks and nightclubs. While they often encountered pity and horror, some of the local barmaids were up to the challenge. Doe still remembers with affection the barmaid at the local pub, noting in his memoir:

Clearly, McIndoe’s patients were facing exceptional psychological stress — and most of them were hardly out of their teens. He responded by encouraging an informal atmosphere that including barrels of pale ale in the ward. Between treatments, the patients were sent to convalescent homes or allowed to stay with family and friends. They were encouraged to wear their own clothes or service uniform rather than hospital attire, and they were encouraged to be social. That meant going to the pub, the theatre, flicks and nightclubs. While they often encountered pity and horror, some of the local barmaids were up to the challenge. Doe still remembers with affection the barmaid at the local pub, noting in his memoir: Can you imagine five or six chaps, some of whom were in a ghastly state with severe burns, walking into a large comfortable bar full of people, (who tended to edge away from this frightful sight!) and being greeted by — ‘My darling — how lovely to see you!” and being given a big kiss! She deserved a medal if anyone did. [Doe, 53]

Yet as time wore on, East Grinstead became so used to the sight of McIndoe’s patients that it was known as “the town that didn’t stare.”

Meanwhile, McIndoe worked wonders. While it was largely up to family and friends to help the young men come to terms with their new faces, McIndoe also worked to find ways to assist in the reintegration of patients in normal life. Very few men were invalided out of the service. Many found non-flying jobs as controllers, intelligence officers, adjutants and the like. Others, however, sought and were allowed to return to full flying duties. Hilary, Page and Doe all returned to full operational flying. Hilary was killed in action in January 1943. Page and Doe both rose to the rank of Wing Commander and survived the war. Below, pictures of all three after their surgery.

Richard Hilary 1942

Richard Hilary 1942

Wing Commander Doe 1943

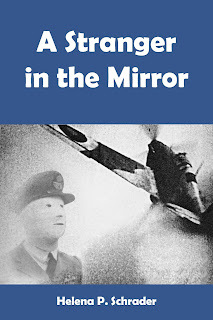

A Stranger in the Mirror tells the story of a pilot shot down in flames in September 1940. Not only is his face burned beyond recognition, he is told he will never fly again. While Dr McIndoe recreates his face one painful operation at a time, the 22-year-old pilot must discover who he really is. Although fictional, the novella draws heavily on autobiographical accounts of Hilary, Page and Doe in describing his treatment and physical recovery.

A Stranger in the Mirror is one of three tales included in Grounded Eagles. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-e...

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

September 24, 2021

British and American Women Pilots in WWII

The Second World War was the first in which women played a role in aviation. Russian women flew combat missions as bomber and fighter pilots, but in Great Britain and the United States the role of women pilots was supportive rather than direct. The similarities and contrasts between the British and American experience are, however, striking. Below is a summary taken from my comparative study published 15 years ago.

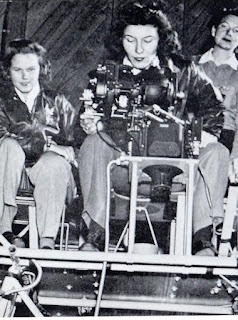

American woman pilot in the cockpit of a B-17 (above)

(Photo courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, No 342-FH-4A05339)

An British woman pilot preparing to fly a Spitfire (below)

(Photo courtesy of Diana Barnato Walker)

In the U.K. women flew with the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), which was founded almost immediately after the start of WWII by senior executives of British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) to employ pilots not fit for military service in supporting roles for the RAF and Fleet Air Arm (FAA). Although it became the sole ferrying organization of the British armed forces, it responded flexibly to other requests and also provided air ambulance, VIP transport and cargo service on an ad hoc basis.

From the start, the ATA was an organization dedicated to providing services, not proving a point, and it was open to both men and women. Indeed, through out its existence, men pilots out-numbered women pilots by a significant margin. For example, the first pilots of the organization were 30 men and 8 women. At it’s peak in 1944, the ATA employed nearly 700 pilots of which only a little over 100 were women. (Source: The Forgotten Pilots. Lettice Curtis (who was herself an ATA pilot). Appendix 1.)

In the United States, in contrast, women flew with the WAFS and/or WASP. Both of the organizations were established as women-only organizations, and the WASP was established more to demonstrate that women could be taught to fly as well as men as to fill any explicit need or shortage identified by the USAAF. Indeed, the USAAF consistently denied the need for training women pilots at all.

WASP in classroom training at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, TX (Photo courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, No 342-FH-4A05376)

The ATA was established by aviation professionals, and initially only accepted pilots with 500 hours of solo time. By the end of 1940, the needs of the organization were so great that the recruiting requirements were reduced to just 50 hours solo, and by 1942 the first candidates without any flying experience were accepted into the organization’s training program. The latter had started in 1941, when the reduction in flying hours required for application had been instituted. Pilots with just 50 hours solo needed additional training to fulfill the tasks assigned.

Rather than duplicating RAF or airline training, however, the ATA inventively developed a pilot training program designed to train pilots precisely for the tasks required by the ATA in a minimum amount of time. Pilots were first trained only on light, training aircraft and then put to work ferrying these aircraft to RAF training establishments. In doing the work, the pilots were already earning their keep, contributing directly to the war effort (relieving RAF pilots from ferrying), and also gaining flying time, experience and confidence.

An ATA pilot in a training aircraft. (Photo courtesy of Michael Fahie)

Once they had fully mastered these aircraft, the ATA pilots (whether men or women) advanced to more powerful single-engine aircraft including fighters, and step-by-step at their own pace to twin-engine aircraft and eventually heavy bombers. At no time were ATA pilots trained on aerobatics, air gunnery, formation flying or other military training irrelevant to ferrying and transport service. Indeed, they were given only minimal training on instrument flying, as ATA pilots were expected to fly “visual.” By keeping the topics of training to the minimum, training time was significantly reduced.

Furthermore, by allowing the pilots to progress at their own pace, no pilots were forced beyond their capabilities. There was no need for all pilots to qualify on all classes of aircraft, a policy that ensured all pilots contributed according to their abilities, reducing accidents and losses. Notably this training scheme was evolved and initially managed by some of the world's finest flying instructors -- instructors that had previously been with the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC).

An British woman pilot in cockpit of a Sterling four-engine bomber (Photo courtesy of Maidenhead Heritage Centre)

The WASP, in contrast, singularly failed to develop a satisfying training program. Training was put in the hands of a civilian contractor of dubious quality, and two separate USAAF inspections of the WASP training facility identified and catalogued myriad inadequacies in the WASP training program, but no corrective actions were undertaken.

Furthermore, the contractor responsible for training rigidly and mindlessly followed the standard USAAF training program (probably at the insistence of the WASP leadership or the USAAF itself). As a result, American women pilot-candidates were subjected to a lengthy course cluttered with utterly superfluous training elements such as mathematics, aerobatics, and use of the Norton Bomb Site -- although no one ever envisaged the women graduates serving as bombadiers on USAAF combat missions.

Above WASP training on the bombsite (Photo courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, No 342-FH-4A05355)

At great expense to the American taxpayer, the WASP training institution at Avenger Field in Texas turned out pilots who on graduation had their wings yet still needed further training before they could contribute to the war effort. Thus while British women pilots were contributing to the war effort after only a few months, the WASP pilots took nine to ten months just to earn their wings. At that point, they still needed specialized training on service aircraft. "Pursuit" training was four weeks long, B-26 training nine weeks and B-17 training twelve weeks long. In short, even the best women pilots were in training for a year or more before starting to contribute to the war effort.

However, because of the substandard level of training offered at Avenger Field, most graduates failed to live up to expectations, fueling rather than diminishing existing prejudices against the concept of women military pilots. Overall, only a tiny percentage of the 1,074 women who passed through WASP training saw active service in any capacity before the decision was made to disband the organization altogether.

WASP pilot and copilot in the cockpit of a B-17 (Photo courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, No 342-FH-4A05519)

PLEASE NOTE! I am NOT suggesting that the American women were in any way inherently less capable or less dedicated than the British women. On the contrary, many American women flew very successfully with the ATA. Women pilots on both sides of the Atlantic consistently demonstrated high levels of competence at least equal to that of male pilots of comparable experience. Indeed, their service record with respect to patience and reliability was notably better than that of male pilots. The women in both countries demonstrated that women could fly the most modern aircraft of their age, (including the first jets in the UK), and their flying safety record was above average in both the U.K. and the U.S.

However, in the course of the war, the women with the ATA steadily won the same privileges and status as their male counterparts. They wore the same uniforms, underwent the same training at the same centralized flying school, and performed the same duties as their male colleagues as they qualified successively on the classes of aircraft from training bi-planes to four-engine bombers. From 1943 onwards, they broke ground by being awarded equal pay for equal work at a time when other women's auxiliaries (such as the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF)) were not. Last but not least, women in the ATA were promoted on merit and could exercise command authority over male colleagues.

Women pilots of the ATA (Photo courtesy of Ann Wood Kelly)

The American women pilots, in contrast, were segregated in an exclusively women's organization. They trained separately at a training base set up exclusively for them and managed, as noted above, by a sub-standard civilian contractor. Even on completing training, they were expressly denied the same uniform, status, rank, privileges, pay and benefits of male pilots engaged in the same activities — whether ferrying aircraft, towing targets or gliders. (The male pilots were all members of the USAAF.) Indeed, the WASP were not even entitled to disability, pension or death benefits in the event of an accident, resulting in the absurd situation in which women killed in the same aircraft as male crew members were denied the military honors accorded the men who had died with them. Separate is NOT equal!

The illusion of militarization: they could march, but not get a pension, disability or military funeral. (Photo courtesy of the National Archives, Washington, No 342-FH-4A05676)

Throughout the war, the women in the ATA were recognized and praised both officially and publicly for their contribution to the war effort. Five women and 31 male ATA pilots won the MBE. Four women ATA pilots and two male colleagues earned the BEM. One woman Flight Captain received a Commendation alongside five male ATA officers, and two women ATA pilots along with 16 male ATA pilots received the King’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air.

The WASP, in contrast, were first glamorized and then demonized. The women could not and did not receive any form or honors. On the contrary, they were sent home before the war was even over, and treated like an embarrassment by the government and nation that had recruited them.

Even more shocking, because of the incompetence of the WASP management, women were sometimes left without pay for months on end. Members were arbitrarily shifted from one assignment to another, preventing the women from gaining experience, competence and confidence in any particular job. They had no uniform for most of their existence, and when a uniform was eventually issued, it highlighted their "otherness" rather than furthering integration and acceptance by the USAAF.

Worst of all, however, the real contributions of competent women pilots were over-shadowed by the bureaucratic back-biting and games played by the WASP leadership. Even USAAF commanders who valued the contributions of individual American women pilots, viewed the organization as a headache. When the WASP became the target of a hostile Congressional investigation, the women pilots found few supporters and so the WASP was rapidly scrapped because it had become a public embarrassment.

A comprehensive comparison of the experiences of women pilots in the U.S. and the U.K. was the subject of my book Sisters in Arms: The Women who Flew in WWII [Pen & Sword, 2006]

![Sisters in Arms: British & American Women Pilots During World War II by [Helena Page Schrader]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1632557784i/31969770.jpg)

September 17, 2021

Footnote to History: The German Aristocracy and the Resistance to Hitler

One curious feature of the German Resistance to Hitler as the disproportionately high number or aristocrats involved. Today I reflect on why.

Peter Count Yorck von Wartenberg

Peter Count Yorck von WartenbergThe German aristocracy was disproportionately well represented in the military resistance and conspiracy against Hitler. For example, the most famous would-be assassin was Claus Count Stauffenberg. Others who volunteered for suicide-attacks against Hitler were Axel Baron von dem Bussche, Georg Baron von Boeselager, and Rudolf-Christoph Baron von Gersdorff — to name just a few. Counts Moltke and Yorck von Wartenburg, and Count Schulenburg were important civilian figures in the conspiracy. Many lesser noblemen were also highly significant figures, for example Henning von Tresckow and Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel. I could list literally hundreds of German aristocrats who were members of the Resistance.

Helmut James Count Moltke

Helmut James Count Moltke The question is: Why was the German aristocracy so prominent in the Resistance? There were two factors:

First, the only resistance group with a chance of successfully bringing down the Nazi regime was that group that controlled some degree of force —i.e. could command troops, had access to explosives and the apparatus of government. This meant the officer corps of the army. While the Communists and Socialists, while staunchly anti-Hilter, they also had a pacifist tradition and so were hardly represented in the Officer Corps at all. In contrast, the aristocracy had for generations been the very backbone of the German officer corps.

Thus the aristocracy dominated the military resistance, that strand of the resistance that made the assassination attempts and carried out the coup attempt.

The second reason for the prominence of the German aristocracy in the German resistance is more subtle but no less significant. In the first half of the last century, the aristocracy in Germany firmly believed that a title of nobility brought with it an obligation to lead and to take responsibility for the fate of the nation.

While Socialist and Communist resistance groups depended on organizations and were thus largely helpless once their organizations were shattered by the Nazis, the aristocracy’s resistance was individual. The majority of those who had formerly voted for the leftist parties became disoriented once these parties were banned and so they were often co-opted by Hitlers early successes—by jobs, higher standards of living, victory.

The aristocracy, in contrast, saw the need to rescue the nation from misgovernment as their hereditary duty—a personal obligation completely disconnected from party affiliation or the existence of an organization.

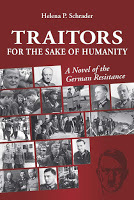

The German Resistance to Hitler was the subject of my PhD thesis. At the time I was the first Western academic granted access to some military archives and documents in what was then still "East Germany." In addition, I conducted interviews with over one hundred survivors of Nazi Germany, both supporters and opponents of the regime. The research culminated in a published dissertation and, later, an English-language biography of General Friederich Olbricht based on the dissertation. It also inspired me to write a novel about the German Resistance, which was recently re-released in ebook format under the title: "Traitors for the Sake of Humanity." Find out more and read reviews of "Traitors" at the publisher's website: Cross Seas Press.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

September 10, 2021

London can Take It -- The Luftwaffe attacks London

As the first week of September drew to a close, the Luftwaffe believed it was winning the war of attrition with the RAF -- but at a higher cost and a slower pace than anticipated. Crews were tired, tempers on edge and the time for an invasion was running out. Hitler extended the deadline for the invasion to September 21 to give the Luftwaffe more time to “soften up” English defenses, but he also expressed doubts about the Luftwaffe’s successes. Goering scented political trouble. He wanted an alternative to “more of the same.” An attack on London seemed just the thing.

The decision to switch the focus of the Nazi air offensive from RAF Fighter Command to the British capital was not made flippantly. The commander of Luftflotte 3, Generalfeldmarshall Hugo Sperrle opposed the move vehemently. He believed the German fighters were greatly exaggerating their claims (whether intentionally or unintentionally) and he doubted that Fighter Command on was on its last legs. He believed that the assaults on the RAF itself should remain the primary objective of the air offensive.

His counterpart in Luftflotte 2, Generalfeldmarshall Albert Kesselring, wasn’t convinced the RAF was broken either, but he noted that (unlike the Dutch, Belgians, and French) the RAF was not allowing itself to be destroyed on the ground. That is, he was fully cognizant of the fact that the Luftwaffe had caught very few RAF fighter aircraft on the ground and drew the incorrect conclusion that the Luftwaffe’s attacks on RAF fighter stations were not terribly effective. He noted further that the RAF possessed a plenitude of airfields beyond the range of his fighters and — since he could not afford to send in unescorted bombers — that meant these fields were de facto immune to attack. Kesselring believed that the RAF defend itself from destruction by pulling their aircraft back to stations beyond the range of the Luftwaffe.

In other words, German ignorance of the vital role of the Sector Operations Rooms at the Sector Control Stations misled the Luftwaffe into underestimating the effect their concentrated attacks on key (albeit not all) RAF airfields had had. This miscalculation, combined with the over-estimation of the losses the RAF suffered in the air, led Kesselring to the conclusion that the Luftwaffe needed to concentrate on a target that the RAF would be forced to defend in the air. The British capital seemed ideal for this purpose.

Goering, however, was probably swayed not by Kesselring’s military arguments so much as by political considerations. He had bragged that the British could not bomb Berlin — but they had. Although the physical damage was nominal, the damage to his reputation was more substantial. “People” were making jokes about him. Far more serious, however, was the fact that Jodl had long advocated an all-out attack on London. In the absence of British pleas for peace negotiations, Jodl sounded more and more convincing. Goering was at risk of losing Hitler’s trust, and in an authoritarian dictatorship the consequences of losing the dictator’s trust were dire.

The bottom line was that Hitlerwanted an attack on London. His patience with the stubborn British — or at least Churchill’s government — had worn out. He might have once admired the British Empire, but he detested being flouted in anything. The fact that an attack on London would contribute little to creating the conditions for an invasion did not interest him. He had never been all that keen on the invasion anyway. There was more than one way to skin a cat. If the invasion was called off, Hitler presumed he could starve Britain with his U-boats while pulverizing her cities from the air. Why waste ground troops he needed to subdue the Soviet Union?

On September 4, 1940, Hitler had promised:

“And should the Royal Air Force drop two thousand, or three thousand, or four thousand kilograms of bombs, then we will now drop 150,000; 180,00; 230,000; 300,000; 400,000; yes, one million kilograms in a single night. And should they declare they will greatly increase their attacks on our cities, then we will erase their cities!

With the dictator so committed to terror bombing, Goering didn’t really have any choice.

On September 7, Goering set out to show Hitler, the German people, and — almost incidentally — the British, just what the Luftwaffe could do. In a maximum effort, 348 bombers escorted by 617 fighters were launched on a single late-afternoon raid. Goering and his field marshals watched through binoculars from the Pas de Calais while picnicking on fine food and selected wines.

The attack caught Air Vice Marshal Park flat-footed. He was himself away at a meeting with Dowding and others. His controllers, anticipating attacks on airfields, kept waiting for the large force to split up into smaller raids. The first squadrons to make visual contact with the raid had never seen anything like it and could hardly believe their eyes. Amazed though they were, a section of three aircraft was detailed to “deal” with the 600 fighters while the remaining nine aircraft attacked the bombers. Naturally, other squadrons were soon sent into the fray as well, but they arrived piecemeal, one or two at a time. The RAF pilots could not see their comrades coming from different stations on different vectors and attacking in a staggered fashion. They were left feeling that they — a squadron or two — were utterly alone against this gigantic air armada.

The Luftwaffe had the same feeling. The RAF did not come up in hoards or swarms, but instead nibbled at the fringes more like irritable gnats than the vicious eagles they had been the weeks before. That is, until they reached London itself. Then more aircraft appeared and a great dog-fight involving close to 1,000 aircraft altogether developed, but it was a fighter-fighter engagement for the most part. Meanwhile the bombers had set the London docks on fire, destroyed a gas works and shattered hundreds of buildings. At the end of the day, the Luftwaffe lost only fourteen bombers, sixteen 109s and seven 110s. That didn’t seem so bad. All the intelligence about RAF attrition appeared confirmed.

Furthermore, with the target now the huge city of London, precision bombing was a luxury. All that mattered was delivering Hitler’s message of vengeance and obliteration until the British surrendered. The Luftwaffe started a round-the-clock bombing offensive, with night as well as daylight raids whenever weather permitted. For the next week, bombing by night and cloud, the Luftwaffe inflicted damage and encountered comparatively little opposition as interceptions went awry in cloud. The impression of a weakening RAF was reinforced.

On Sunday September 15, conditions appeared perfect for a new massive daylight raid on London — a final effort before Hitler decided yea-or-nay about an invasion of England. The Luftwaffe confidently mustered its full strength again and sent the raid in. The RAF, however, knew where they were headed this time. There was no need to hold squadron’s back to protect airfields and radar. Instead, Park timed his interceptions to first peel the German escorts away from the bombers with high level, predominantly Spitfire attacks, and then sent the remaining (mostly Hurricane) squadrons in to take out the bombers after their escorts were fully engaged with the Spitfires. Meanwhile, 12 Group had been alerted of the incoming raid and had time to assemble a “Big Wing” of five squadrons just north of London. By the time the last German aircraft of this raid had landed back at base, it became clear that the Luftwaffe had lost one-quarter of the bombers deployed and more than 12% of the fighters. But this raid had only been the “prelude” to the real strike.

The second raid of the day was composed of 114 bombers escorted by 340 fighters. While smaller than the raid of September 7, the fighter/bomber ratio was higher. AVM Park answered with every squadron he had and then some — 10 Group put up squadrons over 11 Group airfields and 12 Group was asked again to provide a Big Wing over London. BY 14:35 every available RAF squadron was in the air — with PM Churchill at Uxbridge watching the entire show. By evening the RAF was claiming 185 Luftwaffe aircraft for the loss of 28 fighters. Actual Luftwaffe losses were 56. It was now the RAF that was wildly exaggerating their claims, particularly in inexperienced squadrons and those in the Big Wing of 12 Group. But the pilot losses were markedly different. The 81 Luftwaffe airmen had been killed, 63 captured and 31 returned to base wounded. The effective loss to the Luftwaffe was 144 killed and captured. In contrast, 12 RAF pilots were killed and one captured after bailing out into the Channel and being picked up by Luftwaffe air/sea rescue. Even with respect to wounded, the RAF had escaped lightly with only 14 casualties.

The returning bomber crews were shaken. Individual units had sustained casualty rates of 30% or more, the worst being 60%. They were shaken too by head-on attacks that appeared suicidal and ramming that was equally so. The RAF did not look beaten to the pilots and aircrew of the Luftwaffe.

But in the jovial and congenial atmosphere of Goering’s hunting lodge Karin Hall, all was still well. The RAF had only managed to ‘scrape together’ so many aircraft by denuding the rest of the country and concentrating their fighters around London. They had thrown untrained pilots into the fight who didn’t even know how to shoot — which was why they tried ramming their enemy. If only the days were longer and the weather more stable, the Luftwaffe would have air superiority in a day or two. Fortunately for Goering and his commanders, the weather was bad and Hitler postponed “indefinitely” the invasion of Great Britain. The RAF had won the Battle of Britain — the Luftwaffe Leadership just didn’t know it yet.

Where Eagles Never Flew opens with the Battle of France and goes on to show the Battle of Britain, in all its phases, from both sides of the Channel. It does so by following the fate of German characters as well as British ones. The British characters are members of the fictional No. 606 (Hurricane) Squadron based at Tangmere. The German characters are the pilots and women auxiliaries of a Me109 Gruppe based in Northern France. Where Eagles Never Flew is the winner of the Hemingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction, a Maincrest Media Award for Historical Fiction, and more. Find out more about Where Eagles Never Flew at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew or watch a video teaser at: Eagles Video Teaser

September 3, 2021

Western Allied Response to the German Resistance

Although the German Resistance to Hitler was a loose conspiracy based on shared abhorrence of Hitler, his policies and his regime, they did not operate in a vacuum. Hitler's government started the most devastating war in human history and the three greatest powers on earth buried (at least temporarily) their differences in order to defeat Hitler's Germany. At various times, members of the German military resistance sought to establish contact with the Western allies -- and it wasn't all about getting a "better deal" than "Unconditional Surrender."

Tragically, no one was listening.

The German anti-Nazis who attempted to kill Hitler and topple his regime on July 20, 1944 made various attempts to inform the Western Allies of their existence and get assurances that, if they succeeded in removing Hitler and establishing an interim government, the Western Allies would negotiate with them. The first such attempt was made in the lead-up to the Sudeten Crisis in 1938. Via the Vatican, the British government was informed about the possibility of a coup to prevent Hitler from invading the Sudetenland. However, the British government was not interested in aiding German generals against Hitler, and at that time even preferred Hitler to a government run, even temporarily, by the German General Staff. It was a tragic misjudgment.

In the lull between the invasion of Poland and the start of the offensive in the West, one member of the Resistance, Hans Oster, warned the Dutch of the impending violation of Dutch neutrality—a move that has made him very controversial in Germany to this day. But the Dutch didn't take the warnings seriously and were caught off guard despite the warning.

Hans Oster

Hans OsterLater, the Allies were far too committed to Stalin to think of seriously negotiating with a post-Hitler government. In consequence, they responded to all overtures with non-committal answers. Some members of the conspiracy hoped nevertheless that once they had killed Hitler and seized power — i.e. had proved their effectiveness and presented the Allies with a concrete opportunity to stop the loss of life in the West — they might be able to effect at least a ceasefire in the West. Some of the conspirators were willing to open the Western Front to the Anglo-Americans and invite them into Berlin while holding the Russian Front.

The German Resistance to Hitler was the subject of my PhD thesis. At the time I was the first Western academic granted access to some military archives and documents in what was then still "East Germany." In addition, I conducted interviews with over one hundred survivors of Nazi Germany, both supporters and opponents of the regime. The research culminated in a published dissertation and, later, an English-language biography of General Friederich Olbricht based on the dissertation. It also inspired me to write a novel about the German Resistance, which was recently re-released in ebook format under the title: "Traitors for the Sake of Humanity." Find out more and read reviews of "Traitors" at the publisher's website: Cross Seas Press.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!