Howard Yu's Blog, page 6

September 7, 2020

Why Walmart Wants to Buy TikTok? Live Streaming E-Commerce Is The Future

For teenagers, TikTok FOMO—fear of missing out—is real. I had mostly avoided the app; it made me feel old. Then Walmart said it was joining Microsoft in a bid for TikTok. That caught my eye.

Walmart x TikTok. Really?

True, TikTok could be a huge boost for Walmart’s e-commerce business. There might be some potential to cross-sell ads. But that wouldn’t justify a $30 billion price tag. So there has to be more to it.

Over the last few years, Walmart has stepped up its online activities. In the US, it offers curbside pick-ups so people can shop at a safe distance. Customers order things online and drive to a store. A worker then loads everything into their trunk. There’s no need to step inside a crowded store.

In China, Walmart is the only foreign supermarket competing in the country’s massive e-commerce arena. It’s made large investments in JD.com, China’s second-largest e-commerce platform. In 2018, it invested US$500 million in a grocery delivery service, Dada-JD-Daojia.

So Walmart saw first-hand what happened in China during the pandemic. The company understands that the future of e-commerce is in live-streaming. It’s now bringing what it learned from China back to the US. And TikTok is the vehicle.

TV interview on Yahoo Finance: TikTok U.S. sale is not about the algorithm, it’s about the user base.

How a Live-Streaming Craze Turned Into a Lifeline

Consider a well-known case in China, Peacebird. It’s a billion-dollar fashion retailer with seven brands and 4,600 brick-and-mortar stores.

Peacebird chairman Zhang Jiangping responded to the coronavirus outbreak by going all-in on live-streaming. He notified sales agents and authorized them to post content on social media channels. Then, on Jan 28, the company hit a milestone.

Three days into the Chinese New Year, retail director Andre Gao hosted Peacebird’s first live-stream session. Over 100,000 people joined it. Thousands of in-store managers became online sales agents. These agents started to interact with customers on Taobao Live, the live-streaming platform run by Alibaba. They reached as many new clients in three hours as they normally would in six months.

The result? Peacebird made more than 10 million yuan (US$1.41 million) during the first three weeks of the Chinese New Year. This was the same period when the coronavirus ravaged Wuhan and triggered the city’s lockdown. By the second quarter, the company had already seen a 30 percent year-on-year increase in online revenue.

[image error]

The Next Frontier of Shopping

American brands are adjusting to the new retail formats too. Nike’s online sales in China grew more than 30 percent. It went big on Tmall, another Alibaba platform. It hosted the Air Max March Party in April. The launch was broadcast online, attracting 2.7 million viewers and generating 24 million likes. That alone translated into over 5 million yuan in sales in under four hours.

In January, like everyone else, Nike had to close over 5,000 Chinese stores. But its sales revenue for the Greater China region only dipped by 5 percent in that first quarter. By the third quarter, revenue had grown by 5 percent compared to last year.

Walmart is watching with interest.

After all, Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, is a major player in China. It has 13 percent of the live-streaming e-commerce market share. That makes it second only to Alibaba’s Taobao Live.

What happened in China may show Walmart how to beat Amazon in the US by attracting more consumers aged 16 to 24. TikTok has about 100 million monthly active users in the US. Half of them use it daily.

Time Is Ticking On TikTok

Depending on how you look at it, the forced sale of TikTok can be a boon. It’s easy to imagine tens of thousands of TikTokers live-streaming products the same way millennials endorse brands on Instagram. It’s easy to imagine Walmart stepping up its logistic services. Physical stores could serve as fulfillment centers even after the pandemic. Young people could watch TikTok, click, drive to a store, do a curbside pickup, go home. And repeat.

To Walmart, $30 billion for a joint bid for TikTok might well be a bargain. Amazon, don’t complain you didn’t get the memo.

P.S. What’s your view on future retail? Who’s your favorite online influencer? Is live-streaming on TikTok the new infom ercial? Join the discussion below. Love to hear your view.

(An earlier version of this article was co-authored with my colleagues Mark Greeven and Jialu Shan. It was published by Channel News Asia in Singapore.)

The post Why Walmart Wants to Buy TikTok? Live Streaming E-Commerce Is The Future appeared first on Howard Yu.

August 24, 2020

Curiosity Lost? Here’s How to Stimulate It

I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious.

Curiosity is the engine of achievement. It drives our knowledge forward. It tempts us into dangerous and forbidden waters. And it is the foundation of innovation. Steve Jobs took a calligraphy class when he was a student at Reed College. He then hung out for another 18 months, studying the subject like a Buddhist monk. He later credited calligraphy with inspiring Apple’s typography.

In France, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso studied African sculptures. They observed the highly stylized treatment of human faces. Then they combined it with Impressionist painting styles. The result was Cubism—colorful palettes, flatness, and interlocking planes of simple geometric shapes. It revolutionized the modern art scene.

Whether it’s said by Jobs or Picasso, original thinkers are overrated. “Good artists copy; great artists steal.”

What is curiosity?

Curiosity starts with an inquisitive mind. We’re all born with it. Infants prefer to look at new pictures, not familiar ones. Preschoolers play longer with a mechanical toy when it’s harder for them to learn how it works. A curious mind prefers diversion and unplanned excursions. Curiosity is unruly. It disdains approved paths.

As we grow older, some still enjoy mentally challenging activities more than easy ones. These people don’t take shortcuts. They prefer to take the scenic route when trying to make sense of the world. It’s a personality trait that psychologists call the “need for cognition.” It measures how much people love to think deeply, regardless of monetary reward. Are you ready to find out yours?

Try answering the following questions with “true” or “false.” There are only 18 items. Don’t overthink them, and be truthful with yourself. The quiz should take no longer than three minutes to complete.

I prefer complex problems to simple ones.

I like being responsible for situations that require lots of thinking.

Thinking is not my idea of fun.

I would rather do something that requires little thought than something that challenges my thinking abilities.

I try to anticipate and avoid situations where I might have to think deeply about something.

I find satisfaction in deliberating long and hard.

I only think as hard as I have to.

I prefer small, daily projects to long-term ones.

I like tasks that require little thought once I’ve learned how to do them.

The idea of relying on thought to make my way to the top appeals to me.

I really enjoy a task that involves coming up with new solutions to problems.

Learning new ways to think doesn’t excite me very much.

I prefer my life to be filled with puzzles that I must solve.

The notion of thinking abstractly is appealing to me.

I prefer a task that is intellectual, difficult, and important to one that is somewhat important but does not require much thought.

I feel relief rather than satisfaction after completing a task that required a lot of mental effort.

It’s enough for me that something gets the job done; I don’t care how or why it works.

I usually end up deliberating about issues even when they do not affect me personally.

Check if you’ve answered “true” to more than five of these questions: 1, 2, 6, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, and 18. Now check if you’ve also answered “false” to more than five of these: 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 12, 16, and 17. If so, chances are that you have a higher need for cognition than the average person. It means that you intrinsically enjoy cognitively challenging activities.

Why is having a hungry mind is important?

We’re all forecasters. We all want to know what’s going to happen next. When curiosity is triggered, we’re less likely to fall prey to confirmation bias, which occurs when we seek out information that supports our current beliefs and ignore evidence suggesting that we’re wrong. Curiosity counters that tendency because it leads us to generate alternatives.

Without being curious, we can’t learn. Even when we try, we learn the wrong lesson.

“I am 46. I’ve been married for 22 years and we have 3 kids. … I buy more books than I can finish.” That was how Satya Nadella introduced himself in an open letter to Microsoft employees when he was appointed CEO in 2014. “I sign up for more online courses than I can complete. I fundamentally believe that if you are not learning new things, you stop doing great and useful things,” he said.

Nadella was promoted at a time of setbacks. Before him, product flops were common at Microsoft—Zune, Vista, Kin, and Bing. The software giant took a $900 million write-down on unsold Surface tablet inventory. It was losing out to Amazon, Apple, and Google in music players, e-readers, and smartphones. And the PC market was in decline.

Nadella’s letter didn’t mention his predecessor, Steve Ballmer. It emphasized Bill Gates instead. Nadella wouldn’t let profitability alone define his career. Curiosity and hunger for knowledge defined him, he wrote.

Shareholders welcomed the news and the tech press lauded the move. Microsoft’s stagnant share price shot up 7% after the announcement that Ballmer was stepping down.

Some said the disdain for Ballmer was unfair. No company, they argued, could have foreseen Apple’s gains in the mobile space. And Ballmer was the CEO who had tripled Microsoft’s annual revenue from $23 billion to nearly $78 billion. He had introduced best-selling products like Windows 7, which ruled the PC market for almost a decade. They said it was the financial market being unfairly punishing. Back in December 1999, Microsoft’s market cap hit $614 billion. By June 2012, that cap had been reduced to $249 billion. During the same period, Apple’s grew from $4.8 billion to $541 billion.

It’s hard to predict share prices, Ballmer tried to explain. “At the end of the day, they have to have something to do with profit.” But a look at Microsoft’s earnings in relation its share price tells us that’s the wrong conclusion.

Growth prospects, not profits, decide a company’s share price. Profitability is the consequence of decisions made in the past. Because the stock market is forward-looking, it’s futile to trumpet rising profits without showing innovation. That’s why people were tired of Ballmer. His narrow view of how things work led him to draw the wrong conclusions all the time.

If only closed minds came with closed mouths

Three years after stepping down, Ballmer still didn’t understand what he had done wrong with mobile OS. He couldn’t grasp why Microsoft had lost the battle against Apple and Google. The ex-CEO made that point clear at a conference in 2017, when he said Microsoft should have produced its own hardware. This was a way to defend his ill-fated acquisition of Nokia. It only revealed his envy of Apple. He couldn’t accept nor understand the logic of Google’s Android: Software licensing is out. Subscription is in. Everything else is in the cloud. In 2015, Microsoft wrote off $7.6 billion because of the Nokia acquisition. It laid off 7,800 employees, mostly in its phone business, which had become “immaterial.”

No one denied Steve Ballmer had been a great partner to Bill Gates. Gates could think about the future from the stratosphere because Ballmer was the tough obsessive who kept the show on the road. But when he took over as the CEO, Ballmer continued to play the salesman who focused on the company’s bottom line. He once ran to find Yang Yuanqing, the head of Lenovo, at a Microsoft event, yelling at his handler, “Just tell me where he is!” Lenovo is the world’s No. 1 PC maker, and a huge Microsoft customer. Grasping his client’s hand and earnestly talking him up, Ballmer looked like he was in his element—a veteran salesman with a beaming smile. He laughed and clapped during the several-minute conversation. He placed his hand on Yuanqing’s shoulder before embracing his hand once again and departing.

But when asked if Ballmer was ever involved in any product decisions, one longtime designer said a flat “no.” Another added, “Not at all.” Yet another said, “I don’t think Steve could even spell the word design.” Unlike Steve Jobs, who was involved in every aspect of product launch, Ballmer was never hands-on. Nor was he much of an innovator. He simply wasn’t interested. He had no curiosity about an area that needed his attention as a CEO.

Can I feed my mind?

The lack of curiosity among leaders can be comical. Michael Eisner, the former Disney CEO, never bothered to understand Pixar when Steve Jobs led it, even though Disney and Pixar both created animated films. And it was under Eisner that Disney began to distribute Pixar’s movies: Toy Story, Monsters Inc., Finding Nemo, and The Incredibles. This was also a time when Disney’s own animation studio gradually sank into irrelevance. All it released were tepid bummers or outright disasters. There was Fantasia 2000, The Emperor’s New Groove, Lilo and Stitch, Treasure Planet, Brother Bear, and Home on the Range. None were memorable.

Steve Jobs recalled thinking that the CEO of Disney should be curious about Pixar’s success. But Eisner visited Pixar for a total of about two and a half hours over twenty years. He was only there to give little congratulatory speeches. “He was never curious. I was amazed,” said Jobs. The worst thing, to his mind, was that Pixar had already reinvented Disney’s business. It turned out great films one after the other while Disney turned out flop after flop. “Curiosity is very important,” Jobs said.

So how can we make ourselves more curious? What should we do if our “need for cognition” is lower than average? Can we rouse ourselves with a strong interest in important topics?

George Loewenstein, a professor at Carnegie Mellon, gave an answer to this question in 1994, in a classic paper called “The Psychology of Curiosity.” Curiosity is simple, he wrote. It comes when we feel a gap “between what we know and what we want to know.” This gap creates an emotion. It feels like a mental itch, a mosquito bite on the brain. We seek out new knowledge to scratch the itch.

What that means is that that curiosity requires some awareness. We’re not curious when we know nothing about a subject. But as soon as we know even a little bit, we want to know more.

To get this process started, Loewenstein suggests, we should “prime the pump”—give ourselves some intriguing but incomplete information.

Newer research shows that curiosity does indeed increase with knowledge. The more we know, the more we want to know more. That’s why field trips, or learning expeditions, can be powerful prompts for senior executives. They unleash curiosity in otherwise all-too-busy managers. Field trips combine visits, workshops, meetings with experts, and tours of start-ups or even competitors. They can happen on the other side of the globe — think Shanghai, Nigeria, Silicon Valley or Tel Aviv — or they can be right next door. Think co-working spaces and shop or factory visits. Expeditions are most effective when they let us observe places, practices, and people other than those we’re familiar with. They break our usual routines and take us out of our comfort zones. And neuroscientists agree that this is the most effective way for us to learn.

How curiosity prepares the brain for better learning

One interesting neurology study came out from the University of California, Davis. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Matthias Gruber and his colleagues had students answer a series of trivia questions while inside a brain scanner.

After reading each question, the subjects were told to silently guess the answer. They then indicated their curiosity about the correct answer. Did they not care what the answer was or were they “dying” to know? Next, students would see the question presented again, followed by the correct answer. Tha was it.

The first thing the scientists found is that curiosity follows an inverted U-shaped curve. We’re most curious when we know a little about a subject, but not too much, and we’re still not certain of the answer. This supports the information gap theory of curiosity we saw above.

But here’s the wrinkle. In the moments when the question was first asked, if the subject showed a high level of curiosity, the brain would increase activity in three areas. The brain revved up in the ventral tegmental area and the nucleus accumbens. These are the two regions transmitting dopamine, the happy molecule responsible for the sensation of pleasure and reward. But a third region, the hippocampus, which is involved in the creation of memories, also activated.

During moments of peak curiosity, our brains aren’t just primed to learn the answers to trivia questions. They also remember anything surrounding those moments better. Gruber’s team tested this hypothesis further. He presented unrelated faces right after the volunteers were “primed” to be curious. He wanted to know how much people could remember those faces months after the experiment. The result? People could remember more of the information paired with interesting trivia questions than boring ones.

All these things suggest a “thirst for knowledge” is more than metaphorical. Knowledge has a reward value for the brain. When we feel the itch because of what we already know, we’ll enjoy learning more. And we’ll remember it better too. Learning favors the prepared brain. Deprived of curiosity, we end up with impoverished minds.

Prompting Yourself, Every Day

You know these people, or maybe you’re one of them. They’re the kind of people who simply couldn’t put up with corporate nonsense. They are the kind of people who want work to be play. But meaningful play. Henri Matisse. Pablo Picasso. Steve Jobs. Albert Einstein. They are fighting against conformity and drudgery. Whether they know it or not, they prompt themselves to be curious, every single day.

Stay healthy,

P.S. Did you try the survey on “need for cognition”? Were there any surprises? Do you have any tips about staying curious? What’s helped you or your team to learn outside your comfort zone? Let me know in the comments below. Join the discussion.

The post Curiosity Lost? Here’s How to Stimulate It appeared first on Howard Yu.

August 21, 2020

Superpowers Tussle As Home Burns

The United States and China have delayed the review of their Phase 1 trade deal, originally scheduled for last Saturday. The official reason was both sides need time.

The coronavirus dampened China’s economic activities, so it needs more time to buy the required amount of US exports. But the real reason is there’s nothing to discuss. Neither side wants to negotiate. If they did, they would have set a new date. Yet they haven’t. No one knows when the US and China will meet next.Should we be surprised? As recently as last month, US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer said: “I don’t know what the end goal is.”

A review is meant to “figure out new rules”. Lighthizer maintained that the US has worked with allies – he met representatives from Japan and Germany to try and reform the World Trade Organisation (WTO). “What Phase 1 is, is an attempt to find those kinds of rules – and these are setting aside all the aggression in India and Hong Kong,” said Lighthizer. For US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, any discussion would be unbearable. He is chairman of CFIUS (the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US), a panel that reviews TikTok and makes recommendations to US President Donald Trump. His panel urged the president to delist Chinese companies that trade on US exchanges and that do not meet US accounting standards.

What has lead to this?

Trade negotiations have never been downgraded to such a sideshow before. Today, wages in China are higher than in neighbouring countries like Vietnam and the Philippines. The People’s Bank of China spends more time propping up the yuan than driving it down.

It’s not that China doesn’t want to buy from the US. The US$200 billion (S$275 billion) of American goods imported in 2019 was a small portion of the US$2 trillion import trade. It’s the US that doesn’t want to sell what China wants. This moves things away from a trade war to a technology battle.

As part of the Phase 1 agreement, Beijing promised to punish Chinese firms that steal corporate trade secrets. Beijing would stop making Chinese companies obtain foreign technologies through acquisitions. Then came the banning of TikTok and WeChat and the increasing crackdown on Huawei. Washington’s message is clear: We can’t trust China on anything because it’s run by the Communist Party of China. We must stop China at all costs.

These costs would include barring American consumers from choosing TikTok. Thus, the government will basically tell the American people how to use the Internet properly. This unconstitutional act is exactly how TikTok plans to sue the administration in a California court. The costs would include making the iPhone useless among Chinese consumers by banning WeChat from Apple’s App Store. It’s the same realignment between business and government that happens during wartime.Historians will study how, under Trump’s administration, the political elites are flipping from being “Panda huggers” to “China hawks.” But if any side is to win, it needs an ally. And neither is building any alliances.Beijing has hardly won any friends abroad lately.

There were the China–India skirmishes. Hong Kong events damaged its relationship with the UK. Tensions with Japan are rising over disputed islands. Then there’s the contested territory in the South China Sea, with Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei all staking their claims.Meanwhile, Trump is rejecting cooperation with American allies. He threatened to overturn Nafta (North American Free Trade Agreement), on which essential supply chains in Canada and Mexico depend. He plans to upend the World Trade Organisation. He signals formal withdrawal from the World Health Organisation (WHO). He attacks Nato (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation). He is pushing the US toward isolation to make it great again.

So, where does it leave Europe and a host of other smaller economies? What could be the outcome?

It’s human nature to assume one side will eventually win. The Cold War ended with the liberal triumph of the west. And so, the US must ensure a western world order that will last for another 100 years. But what if it can’t? Not that China will dominate the west – it can’t. Instead, the two economies, the two political systems, the two vastly different sets of values will co-exist, forever. One can no longer claim superiority over the other. The coronavirus outbreak has been the latest judge. Despite plenty of warnings, the west couldn’t mobilise its resources. This has taken the world by surprise. It has become clear that governments in the US and Europe can’t safeguard their populations. Instead, Asia – South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore – have been hailed (at varying times) as the role model. These countries haven’t copied western ideals wholesale.

Then again, never mind about who’s going to win over the next 100 years. The US can win and hold back China’s technological development. But without an advanced solution, China will keep pumping out greenhouse gases. And the flooding in Florida and New York City, the wildfires in California and the drought in the Midwest, will turn America into a living hell. That is the great dissonance.

The trade talks are infected by geopolitics, which in turn obsess over national dominance. The narrative is stuck at a point 50 years ago, when no global crisis existed. Behind the Iron Curtain, people lived independently. Nations can pick sides. Yet politicians, having grown up in the last era, still obsess over winning an outdated battle. In this scenario, though, nothing is waiting for them behind the finish line. There will be no gold trophy. The two superpowers will wake up, eventually. The worst nightmare would be mitigated to a degree. So it’s not a question of If, but When.

Meanwhile, smaller countries will position well by practising an open economy and international trade. When Hong Kong’s leading position as a financial hub is being threatened by the US sanction, Singapore may mobilise resources to take full advantage. Under pressure from the United States, Israel announced late last year that it would form an oversight panel to scrutinise Chinese investment. But scrutinising foreign investment in Israeli technology start-ups was not included in the panel’s mandate. Germany is going to look at China differently than England. For now, government agendas are driving businesses. But the fight between the two giants won’t last, because it doesn’t solve the real threat to humanity itself. The tenet for success among smaller nations remain unchanged: widen trade with China when possible and indulge American demands when necessary.

Originally published on The Straits Times

Outlast your competition and thrive in an ever-changing world

In Leap, Howard Yu, LEGO professor of strategy and innovation at IMD, explains how companies can prosper, not just survive. Leap identifies five fundamental principles that allow companies to stay successful in the face of such competition.

The post Superpowers Tussle As Home Burns appeared first on Howard Yu.

August 9, 2020

Governments are Cracking Down on TikTok and WeChat. Here’s What Smart Managers Can Learn From That.

Businesspeople have long despised politics. But “politics” is now shaping strategy. It affects boardrooms as much as assembly lines. The Trump administration is turning up the heat on TikTok and WeChat. An executive order will stop US companies from doing business with them. In 90 days, the Apple App Store won’t be able to feature the two Chinese apps. The administration has also recommended removing all Chinese companies from US stock exchanges unless they give US regulators full access to their accounts.

Thanks to the tight deadline, Microsoft is likely to snap up a crown jewel at a discount. TikTok remains the fourth most popular app in the world. Zhang Yiming, the chief executive of ByteDance, which owns TikTok, told employees he has no choice but to abide by US laws.

Trump also said the US Treasury should get “a very substantial portion” of the sale price. That’s “because we’re making it possible for this deal to happen.” The mechanics of this are unclear. But Microsoft said it “appreciates the US government’s and President Trump’s personal involvement.”

The Trumpeting of a National Purpose

The US government hasn’t intervened in business so forcefully since World War II. It’s one thing to demand that businesses be socially responsible toward local communities. But now it seems acceptable for the government to crack down on foreign companies and to profit from doing so. What the White House creating is a new norm around the world.

Governments everywhere now feel compelled to intervene in a company’s operations. Concerns include “privacy protection,” “national security,” “local jobs” or the “local economy.” India has already banned TikTok, WeChat and another Chinese tech company, Baidu. The UK is removing Huawei from its telecoms network. Japanese clothing retailer Uniqlo is closing stores in South Korea amid an ongoing trade dispute. Apple faces a Siri patent fight that may block iPhone sales in China.

Absent from these situations are intergovernmental organizations. The crackdown on TikTok and WeChat is driven by Trump’s executive order. The World Trade Organization (WTO) has mishandled trade negotiations for too long. It can’t meaningfully mediate between countries anywhere. This means the burden of doing business falls back on executives.

A Game of Chicken

Before the WTO, tariffs were everywhere. In 1963, for example, then US President Lyndon Johnson imposed a 25% tariff on light trucks imported to the US. This was payback for European tariffs on American chicken. Johnson signed the “chicken tax,” as the tariff on became known, just before the 1964 election. Members of the United Auto Workers union from Detroit were threatening to call a strike, and the tax gave them what they wanted. Sales of Volkswagen trucks and vans in the US plummeted.

Without the WTO to prevent this kind of dispute, companies had to come up with their own solutions. Mercedes was one that managed to avoid much of the pain. For years, the German automotive manufacturer disassembled its vehicle parts and shipped the pieces to South Carolina. There, American workers put them back together in a small kit assembly building. These vehicles were “locally made,” so they escaped the import tariff. The extra costs of this method were nothing compared to Mercedes’ profits.

How Managers Can Respond

Today’s economic and political dispute between the US and China make the “chicken tax” battle seem minor. The value of US imports at stake in the countries’ next negotiation is US$200 billion (£153 billion). Because of the trade hostilities, US-listed firms have lost some US$1.7 trillion of their value over the past two years.

One immediate consequence is that US companies are moving manufacturing activities out of China. Instead, they’re choosing places like Thailand and Vietnam and Bangladesh. The most successful executives recognize the need to align business practices with politics and switch to new operating models quickly.

Zoom, for instance, has stopped selling new and upgraded products directly to customers in mainland China. Instead, it’s shifting to a “partner-only model” in the country, outsourcing commercial activities to Bizconf Communications, Suiri Zhumu Video Conference and Systec Umeet. It’s the sort of partnership model that Microsoft also has in China for cloud-computing service Azure.

In the financial sector, stored data has become the most sensitive issue. In Europe, German and French officials are talking about creating a continental cloud service for banks. This service would be run by local tech companies. This move is part of Europe’s strategy for “ensuring technological sovereignty and reducing its dependence” on US providers. Countries no longer think it’s safe to just buy from Amazon, Microsoft, or Google.

All these things are extra burdens that executives who are already too busy have to think about. As I argue here, it’s now even more urgent to automate everyday decisions with AI. When everything is done manually, is it any wonder that many leaders are stuck clearing their email inboxes at midnight? With no time to think and no time to plan, no one can be ready for the future.

For TikTok, There is No Time

If TikTok disappears after September, it’s not because the company didn’t try. Long before Trump took notice, founder Zhang Yiming tapped Disney’s head of streaming. Kevin Mayer, to run the platform. If perception is reality, having an American CEO as the face of the company’s global operation is a no-brainer. But in this case, it’s more than window dressing. TikTok has been storing user data in servers located in the US and Singapore. That lets it boldly claim all its data centers are located outside China, and none of its data is subject to Chinese law.

To shore up this commitment, TikTok is opening a $500m data center in Ireland. At the same time, it’s talking with Microsoft about a potential buyout and with Twitter about a merger. It’s showing a lot of spunk for a company in danger of being crushed by a government. When the dust has settled, TikTok will at least be remembered as a heroic corporate player. It’s just one caught on the wrong side of history.

Stay healthy,

P.S. How do you think the internet will look in five years? Have geopolitics affected your industry? What role can a smaller economy play during rising tensions between China and the US? L et me know your thoughts in the comments below. Join the discussion.

The post Governments are Cracking Down on TikTok and WeChat. Here’s What Smart Managers Can Learn From That. appeared first on Howard Yu.

TikTok and Microsoft: government agendas are driving businesses like no time since WW2 – here’s what they can do about it

The Trump administration has turned up the heat on Chinese tech companies TikTok and WeChat with an executive order that US companies have 45 days to stop transacting with them. The administration has also recommended that Chinese firms listed on US exchanges be removed unless they provide US regulators access to their audited accounts.

It comes only days after the US president gave the go-ahead for Microsoft (or rival US bidders) to buy TikTok if the purchase can be completed by September 15. Failing that, Trump says he will shut down the video-sharing app in the US. Zhang Yiming, the chief executive of ByteDance, which owns TikTok, wrote to employees telling them he has no choice but to abide by US laws.

Thanks to the tight deadline, Microsoft is likely to snap up a crown jewel at a discount – TikTok is the fourth most popular app in the world. Trump also said the US Treasury should get “a very substantial portion” of the sale price, “because we’re making it possible for this deal to happen”. The mechanics of this are unclear. Microsoft said it “appreciates the US government’s and President Trump’s personal involvement”.

Business and the national agenda

Not since the second world war has the US government expected big businesses to champion a national agenda in this way. It’s one thing to expect businesses to be socially responsible toward local communities. But to ban access of foreign companies, and then to expect domestic companies and the government to profit profit directly from it, is a dangerous line to cross.

Most dangerous is to expect big companies to carry out “national duties” because the country is facing “foreign adversaries”. Do it my way, the leader might say, or I could break you apart. After all, this comes at a time when the excessive size and power of tech rivals such as Google, Facebook and Amazon is already the subject of a fierce congressional debate.

What the White House has set in motion is in fact a new norm around the world. Governments now feel compelled and are urged to intervene in a company’s operations because of concerns over “privacy issues”, “national security”, “local jobs” or the “local economy”.

India has already banned TikTok, WeChat and another Chinese tech company, Baidu. The UK is removing Huawei from its telecoms network. Japanese clothing retailer Uniqlo is closing stores in South Korea in the midst of the ongoing trade dispute.

In the fog of these skirmishes, there is a total absence of intergovernmental organisation. The crackdown on TikTok and WeChat has been instigated purely by Trump’s executive order. When it comes to trade disputes and tariffs, the World Trade Organization (WTO) is delegitimised so completely through long failures over world trade negotiations, the dispute settlement arm and so forth, that it is unable to meaningfully mediate between countries anywhere. This means that the burden of doing business falls back entirely upon executives.

Before the WTO, tariffs were everywhere. In 1963, for example, the then US president, Lyndon Johnson, imposed a 25% tariff on light trucks imported to the US. This was to retaliate against European tariffs on American chicken imports. The “chicken tax”, as the tariff on light trucks became known, was signed as representatives of the United Auto Workers union from Detroit were threatening to call a strike just before the 1964 election. Johnson’s tax gave them what they wanted: Volkswagen sales of trucks and vans in the US plummeted.

Without the WTO to prevent this kind of dispute, companies had to rely on their own ingenuity. Mercedes was one that managed to avoid much of the pain. For years, the German automotive manufacturer would disassemble its vehicle parts and ship the pieces to South Carolina, where American workers put them back together in a small kit assembly building. The resulting vehicles were, therefore, “locally made” and free of the import tariff. Any additional costs resulting from this roundabout method were negligible in comparison to Mercedes’ profits.

How companies can respond

Today’s economic war between the US and China and the escalating political dispute dwarfs any “chicken tax” in magnitude. The amount of US imports at stake in the countries’ next negotiation during mid-August is US$200 billion (£153 billion). As a result of the trade hostilities, some US$1.7 trillion has been wiped off the value of US-listed firms over the past two years.

One immediate consequence is that US companies are moving manufacturing activities out of China, to places like Thailand and Vietnam and Bangladesh. Successful executives are those who are capable of recognising the need to change business practices ahead of political sentiment and pivoting toward a new operating model quickly, whether in China or by moving to new markets.

Zoom, for instance, has stopped selling new and upgraded products directly to customers in mainland China. Instead, it is shifting to a “partner-only model” in the country, outsourcing commercial activities to Bizconf Communications, Suiri Zhumu Video Conference and Systec Umeet. It’s the sort of partnership model that Microsoft also has in China for cloud-computing service Azure.

To see what lies ahead, effective managers look to extreme cases in sectors other than their own. Nowhere is stored data more sensitive than in the financial sector. In Europe, German and French government officials are in talks to create a continental cloud service run by local tech companies for banks. This is part of Europe’s strategy for “ensuring technological sovereignty and reducing its dependence” on US providers. It’s not safe enough to simply buy from Amazon, Microsoft or Google.

All these are extra burdens and considerations for executives who are already too busy. As I argue here, automating mundane decisions using AI is now of even greater urgency.

Business people have long despised politics. But “politics” is now shaping corporate strategy from boardrooms down to assembly lines. Some such as Zoom, and once upon a time Mercedes, adapt to this climate and thrive. Others like TikTok are finding themselves caught on the wrong side of history.

Originally published on The Conversation

Outlast your competition and thrive in an ever-changing world

In Leap, Howard Yu, LEGO professor of strategy and innovation at IMD, explains how companies can prosper, not just survive. Leap identifies five fundamental principles that allow companies to stay successful in the face of such competition.

The post TikTok and Microsoft: government agendas are driving businesses like no time since WW2 – here’s what they can do about it appeared first on Howard Yu.

August 3, 2020

The Personal And Professional Importance Of Having A Fluid Identity

Smart leaders read. They read a lot. Bill Gates reads about 50 books a year. Former PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi read 10 textbooks on one holiday. Nike founder Phil Knight “loved to read.” Warren Buffet reads between 500 and 1,000 pages per day. And when someone asked Tesla’s Elon Musk how he learned about rockets, he said, “I read books.”

Reading vastly wouldn’t matter much if our world moved slower. But the pace of change is speeding up, in artificial intelligence, materials research, engineering, biology, climate science, and geopolitics. In short, it’s everywhere.

People can’t cope with limited mental tools. Without inspiration, people can’t think creatively. They can’t come up with original solutions. They don’t have the courage to change direction.

So it’s interesting to see just how leaders struggle. After all, they’re the ones with plenty of help: market intelligence, external board members, managers who ferret out information. Yet, a leader can get locked into a strong identity and be unable to get out.

The Danger of a Strong Identity

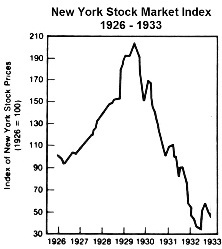

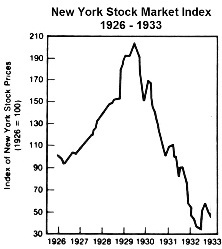

In 1929, a crisis hit Wall Street. On Black Thursday, October 24, a record 12,894,650 shares were sold. The stock market plunged the following Tuesday, October 29, with another 16,410,030 shares dumped. Stock tickers at the New York Stock Exchange ran hours behind. The trading volume was too large.

Soon enough, companies were having trouble getting loans from banks. They laid off workers. Workers who lost their jobs bought fewer products. A vicious cycle ensued.

Presiding over the Great Depression was Herbert Hoover. The 31st president of the United States was an ardent conservative. He saw self-determination as the key to recovery. He believed in self-governance. He preferred authority to rest with the locals. He saw individual freedom as the essence of America. Nothing should challenge people’s initiative. And nothing was worse than a drift toward European paternalism and state socialism.

In the next two years, the unemployment rate would climb from 3 percent to 25 percent. Some 15 million people would become jobless. The stock market would drop to about 20 percent of its earlier worth. By 1933, more than 5,000 banks, nearly half of America’s total, failed. But instead of changing direction, Hoover persisted in his beliefs.

Why Loyalists Don’t Care about Policies

Psychologists have found that people vote mainly based on their own identity. People don’t read actual policies.

Imagine a law is put forward that calls for higher taxes to fund elementary schools. Would you think, “I don’t have any children, so I won’t benefit from the law?” If you’re like a typical voter, the answer is no. Instead, this is how most people think: “I believe in education, so I’ll support this.” Or, “I don’t believe in the public-school system, so I won’t support this.” Who you are and what you believe matter the most. The actual policies don’t count much.

Research shows something else. The more important someone’s political identity is to how they see themselves, the more likely they are to fall in line with the party’s stance. That’s when people vote for a candidate that they dislike. Even if they disagree, they’ll say, “I am a Democrat. This is how we Democrats vote.”

But researchers from London Business School and Chicago Booth found an exception. They found that party affiliation can have less influence among voters who see politics as unimportant. These are the people who limit their political views to a small part of their identity.

We know these people. They are the swing voters. They shift who they vote for instead of letting political identity take over their entire self-regard. They adjust to the changing circumstances because they have a more fluid identity.

For leaders, having a fluid identity can be vital.

I’m Right; You’re Wrong

Hoover understood the cause of the Great Depression with amazing clarity. As early as 1923, before he was president, Hoover warned that the booming economy of the 1920s would soon end. He was concerned about the New York banks who lent money to investors. He worried about investors who bought stocks “on margin.” And yet, he handled the Depression with the conviction of a religion.

Hoover’s “rugged individualism” made him hate direct aid. It’s immoral to tax people who work hard and to give handouts to people too lazy to work. Every person should manage their own well-being. “We cannot squander ourselves into prosperity,” he repeatedly said.

Meanwhile, despair was stalking city streets as well as the countryside. Shantytowns of the homeless—now called Hoovervilles—spread across the US. Americans everywhere were asking for help. But as the shouts got louder, Hoover listened less and then stopped listening altogether. He sent letters saying he was too busy to receive any delegation. He had police reinforce the White House. Nearby streets were closed to traffic. Barricades were erected. In July 1932, Hoover sent in the army. Fixed bayonets and tear gas drove protesting veterans out of Washington.

Crisis Doesn’t Reveal Character, Identity Does

To be sure, the idea of injecting money into the economy didn’t exist at the time. No one in the government knew how to end the Depression. Quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve was a novel concept.

Still, traditional conservatism had its grip on the president. His aides formed a toxic bubble that excluded all other considerations. Some of his fellow lawmakers felt the Depression was getting worse, not because Hoover wasn’t doing enough. They thought he was doing too much!

All of this was leading to the end of Hoover’s one-term presidency in 1932. He once won the election by a landslide. But by the second time he won in only six states. His loss included his native state of California.

Keep Your Identity Fluid in Business

Hoover could have prevented that disastrous outcome. But he would’ve needed to picture a new identity. An identity explains who we are and why we behave in a certain way. Changing identity is hard. It demands mental flexibility, a mix of metaphors and symbols. An entrepreneur might say, “I’m building the Uber for X.” Or, “It’s like Netflix for Y.”

A textbook case in business is how Fujifilm became a chemical giant. Polaroid, on the other hand, became bankrupted. All because they chose their identities differently.

Fujifilm and Polaroid seemed similar on the surface. Both depended on film sales. But they had different reactions to digital imaging. Fujifilm adopted a broad identity as an “information and imaging” company. They saw digital imaging as part of their main business. Meanwhile, Polaroid chose a narrower identity as an instant photography company. Digital imaging challenged that identity. Polaroid resisted it, which led to its own demise.

Identity thus shapes the overall logic of a business. It guides the deeper expression of the everyday activities. It reflects and gives meaning to the concrete and the real. But when it starts to become unsuitable, leaders must avoid getting locked in. Effective leaders never allow their histories and their views of themselves to take them hostage in a new situation.

How To Change Your Own Identity

Here is the first step to reinvention: Build up a wide range of possible selves. Comparing yourself to industry peer groups only leads to a dead end. Copying others’ best practices will at best help you become a fast follower. The most effective plan is to borrow industry logics from other fields and to then mix and match them according to your own needs. You need to reinvent on your own ground.

Having a wide range of possible selves is important on the personal level too. Research has shown that during a career transition, successful managers tap into many role models. They understand the big difference between imitating someone wholesale and borrowing selectively from various people. They prefer to create their own collage.

That’s why reading autobiographies has great benefits. You learn about what a person has been through and how they act in specific situations. They show you how to deal with difficult stages of life. But more importantly, the great personalities we read about become our virtual mentors. They widen our range of thought. Their stories provide ingredients for us to experiment with. Inspiration always comes from daily things. Like chameleons, we can borrow styles and tactics from other successful people, even if we don’t agree with them completely.

Bill Gates doesn’t start a book unless he knows he’s going to finish it. Even when he disagrees with the author, Gates says, “it’s my rule to get to the end.” If he disagrees with a point, he writes his own viewpoint in the margin. Then he goes on to read about 50 more books a year.

Warren Buffet goes further:

“Read 500 pages like this every day. That’s how knowledge works. It builds up, like compound interest. All of you can do it, but I guarantee not many of you will do it.”

Stay healthy,

P.S. What are your thoughts? Do you have any tips about reading habits? What has helped you or your company reinvent yourselves in the past? Please let me know in the comments below. Join the discussion.

The post The Personal And Professional Importance Of Having A Fluid Identity appeared first on Howard Yu.

Fluid Identity: Your Corporate Strategy Depends on It. Here’s How You Can Achieve It

Smart leaders read. They read a lot. Bill Gates reads about 50 books per year, which breaks down to about one per week. Former PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi read 10 textbooks from cover to cover over one holiday. Tesla’s Elon Musk taught himself rocket science because, as he put it, “I read books.” Towering above all is Warren Buffet, who reportedly reads between 500 and 1,000 pages per day.

It wouldn’t matter so much if our world moved slower. But the pace of change is only quickening by the day, be it in artificial intelligence, materials research, engineering, biology, climate, or global politics—in short, everywhere. Those who carry with them fewer mental tools to explain things are suffering. They can’t think laterally. They can’t come up with original solutions. They don’t have the courage to take a different tack. In short, they can’t cope.

It’s interesting to see just how leaders lose grip on reality. After all, they are the ones with plenty of help: market intelligence, external board members, managers who ferret out data of any sort. Yet, a leader can get locked into a strong identity and not be able to get out.

The Danger of a Strong Identity

In 1929, a crisis hit Wall Street. On Black Thursday, October 24, a record 12,894,650 shares were sold. The stock market plunged the following Tuesday on October 29, with another 16,410,030 shares dumped. Stock tickers at the New York Stock Exchange ran hours behind because the trading volume was too large.

Soon enough, companies were having trouble getting loans from banks, so they were forced to lay off workers. People who became unemployed bought fewer products. A vicious cycle ensued.

Presiding over the Great Depression was Herbert Hoover. An ardent conservative, the 31st president of the United States saw self-determination as the key to recovery. He believed in self-government. He preferred decentralizing responsibilities to the local base. He thought individualism was the essence of America, that nothing should ever undermine an enterprising individual whose self-initiatives would grow into greatness someday, and that nothing was worse than a drift toward European paternalism and state socialism.

In the next two years, unemployment would soar from 3 percent to an all-time high of 25 percent, totaling some 15 million people. The stock market would be reduced to about 20 percent of its initial worth. By 1933, more than 5,000 banks, nearly half of America’s total, had failed. Instead of changing tack, Hoover persisted in his initial belief.

Why Party Loyalists Won’t Consider Policies

Psychologists have long observed that people vote primarily based on identity, not on actual policies. When a potential legislation calls for higher taxes to fund elementary schools, for instance, a typical voter won’t consider, “I don’t have any children, so I won’t benefit from the legislation.” Instead, the person is likely to think either (a) “I am a person who supports schools; therefore, I will vote for this,” or (b) “I am a person who doesn’t believe in the public school system; therefore, I will not vote for this.” Who you are and what you believe matter more than the actual policies.

Research shows that the more central a role political identity plays in the way people see themselves, the more likely they are to vote along the party line. They vote even when they dislike their party’s candidate. “I am a Democrat, and this is how we Democrats vote”—so goes the thinking.

Conversely, London Business School’s Stephanie Chen and Chicago Booth’s Oleg Urminsky found that party affiliation has less influence on the way people vote among those who see politics as a peripheral aspect of, rather than central to, their personal identity.

These are independent voters who limit party affiliation to a small part of their being. Instead of letting political identity take over their entire self-regard, they allow themselves to be swing voters. They swing because their identities are more fluid. They would adjust based on the changing circumstances.

For leaders, this ability to adjust can prove vital.

I Am Right, You Are Wrong

Hoover understood the cause of the Great Depression with amazing clarity: As early as 1923, before he became president, Hoover publicly warned that, sooner or later, the booming economy of the 1920s was going to go bust. He was concerned about New York banks’ dangerous practice of lending money to investors so that they could buy stocks “on margin.” And yet, he handled the Depression with the conviction of a religion.

Having grown up with a belief in “rugged individualism,” Hoover seemed to affirm that in America, each individual was responsible for their own well-being. He despised direct aid. The thought of giving handouts to people too lazy to work and then tax others who worked hard was immoral. “We cannot squander ourselves into prosperity,” he repeatedly said.

Meanwhile, despair was stalking city streets as well as the countryside. Shantytowns of the homeless—now called Hoovervilles—spread across the nation. Americans everywhere were asking their government for help. But when the shouts got louder, Hoover heard less and then stopped listening altogether. He sent letters saying he was too busy to receive any delegation. Reinforced police patrols surrounded the White House; barricades were erected to close the nearby streets to traffic. In July 1932, the President had the army, with fixed bayonets and tear gas, drive protesting veterans out of Washington.

Crisis Doesn’t Reveal Character, Identity Does

It’s true that no one in the government at the time knew what was needed to end the Great Depression. The idea that a central bank could have bought government bonds to inject money into the economy didn’t exist. The intellectual architecture for that kind of intervention—quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve—wasn’t around yet.

Still, the grip of the identity of traditional conservatism, aided by the President’s allies, had formed a toxic bubble that barred all other considerations. To some of his fellow lawmakers, the Depression was exacerbated not because Hoover wasn’t doing enough, but because he was doing too much!

Keep Your Identity Fluid in Business

That catastrophic outcome was hardly predetermined. To visualize a new identity, however, would require not only mental flexibility, but the mixing of metaphors and symbols. An entrepreneur might say “I’m building the Uber for X,” or “It’s like Netflix for Y.” An identity is a reflection of the concrete and real, which explains who we are and why we behave in a certain way. It also dictates what problems a company will solve for its customers.

A textbook case in business is how Fujifilm (still a chemical giant) and Polaroid (now bankrupted) chose their identities differently.

On the surface, Fujifilm and Polaroid were similar: They were both dependent on film sales. However, they had different reactions to digital imaging, based to a large extent on identity. Fujifilm adopted a broad, robust identity as an “Information and Imaging” company and explicitly included digital imaging in its set of activities. Polaroid, meanwhile, maintained a narrower identity as an instant photography company. Digital imaging challenged Polaroid’s identity, and the company’s resistance to it ultimately led to its demise.

Identity thus provides an overall logic as well as a clearer and deeper expression of a firm beyond its everyday activities. It’s a leader’s job to avoid being locked into one single identity when it becomes unfit.

To do this well, one must possess a wide repertory of possible selves. Benchmarking one’s company against industry peer groups only leads to a dead end. Copying others’ best practices will, at best, help you become a fast follower. Most effective is to borrow industry logic from other spheres, and then mix and match according to your own need. You need to reinvent on your own ground.

Change Your Own Identity

At a personal level, it’s important to have a wide range of possible selves too. During career transition, for example, successful managers are the ones who actively tap into diverse role models. Research shows that they intuitively understand the big difference between imitating someone wholesale and borrowing selectively from various people to create your own collage, which you then modify and improve.

Most of us have personal narratives about some defining moments that taught us important lessons. But the most effective leaders never allow the stories of their past and the images they have painted of themselves to take them hostage in a new situation.

That’s why reading autobiographies has great benefits. Not only do you get to learn about what an individual has been through and, more often than not, gain knowledge regarding how to act in specific circumstances and deal with difficult stages of life, but the great personalities we read about are virtual mentors who widen our range of thought. Their stories provide ingredients for us to experiment with. Like chameleons, we borrow styles and tactics from successful people, even if we don’t agree with them completely.

Bill Gates does not start a book unless he knows he is going to finish it. “It’s my rule to get to the end,” even when he disagrees with the author. If he disagrees with a point the author makes in the book, he writes his own viewpoint in the margin. Then he goes on to read about 50 more books a year.

Warren Buffet would go further:

“Read 500 pages like this every day. That’s how knowledge works. It builds up, like compound interest. All of you can do it, but I guarantee not many of you will do it.”

Stay healthy,

P.S. What are your thoughts? Any tips regarding reading habits? What has helped you or your company reinvent in the past? Please let me know in the comments below. Join the discussion.

The post Fluid Identity: Your Corporate Strategy Depends on It. Here’s How You Can Achieve It appeared first on Howard Yu.

July 28, 2020

Four Top Tech CEOs Testify In Washington Now. Here’s How This May Affect Your Tech Life

Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Apple’s Tim Cook and Google’s Sundar Pichai are set to speak before the House Judiciary Committee’s antitrust panel on Wednesday. The session will be the sixth hearing in the Judiciary Committee’s ongoing investigation into the nature of digital competition and the anti-competitive behaviors by tech giants. All eyes are on the four key topics that lawmakers will be debating, for their results will shape personal technologies in the coming years.

1) Tech Companies Are Huge. Are They A Bad Monopoly?

Big Tech keeps getting bigger, even during the coronavirus pandemic. Their stocks, which were hit in the first weeks of the pandemic, are now on an upward march to the top of the market cap heap. Just four firms are worth a combined $4 trillion. Just four firms make up over 20 percent of the S&P 500. How could they have been allowed to grow so huge without hearing a whimper from regulators in the past?

Our current interpretation of antitrust law has made it practically toothless to curb any software-driven companies. Since 1979, the Supreme Court has focused on a “consumer welfare” theory of antitrust law. An act is deemed anticompetitive “only when it… raises the prices of goods above competitive levels or diminishes their quality.” Its intention is to protect consumers, and it works wonders for the traditional economy, by regulating the oil and gas, telecommunications, auto, real estate, and consumer packaged goods industries.

But in the digital economy led by software development, any additional users served will incur few additional costs. Once a piece of software is written, it costs nothing to duplicate. Tech companies also know how to get money elsewhere. It’s the advertisers, like P&G and Nike, who pay Google so that we have Google Maps and Gmail. It’s Netflix who pays AWS some $10 million a month for cloud computing so that Amazon can cross subsidize home delivery at a loss. All of a sudden, it becomes less clear if you and I are worse off or better off because of Silicon Valley.

What we need to watch out for is whether Washington will push for a new interpretation of antitrust law. Instead of relying on an outdated doctrine designed for the last century, regulators will instead pay attention to behaviors that harm competitors. Are tech companies systematically eliminating major competitors or depriving other companies of a fair opportunity to compete? Rather than looking at product price, regulators will look at industrial concentration.

2) Are Tech Companies Playing A Fair Game?

Being big gives you big advantages. “Facebook’s killing Snap. Are they doing that in reasonable ways? They’re copying them. Are they better than them, or are they actually doing this in unfair ways?” asked Tim Wu, a professor at Columbia Law School. Once a radical thought belonging only to the liberal Left, this congressional hearing will also likely ask whether smaller companies are being unfairly impaired. That was the logic when the Justice Department was claiming jurisdiction over Apple earlier this year, after the Dutch investigation into the company for favoring its own apps, like Apple Music, over third-party apps like Spotify.

We should look at how lawmakers investigate Microsoft. Slack’s European Commission filing claims that Microsoft’s bundling of its Teams product with the Office software suite is illegal. The fear is that Microsoft is deploying an “embrace, extend, and exterminate” strategy, an approach that exterminated Netscape two decades ago. As Teams is rolling out new features in catching up with Zoom, the result of the hearing might determine whether Zoom might become the next Netscape. Will we still be using Zoom for our next virtual party?

3) Are They Safe, Are They Good?

Although the hearing isn’t technically about ethics, Mark Zuckerberg is unlikely to escape the same questions he’s been bombarded with over the last two years. What will be interesting to watch is whether there is any shift in his tone. Earlier this month, the Facebook CEO told employees in a town hall meeting that he was reluctant to bow down to the threats of a growing ad boycott, saying, “My guess is that all these advertisers will be back on the platform soon enough.”

That is a stunning statement, given that the boycott now includes some of the largest brands out there, including Unilever, Starbucks, Levi, and Coca-Cola. Big brands are boycotting because their consumers are sick of seeing product promotions on a platform that encourages hate speech, misinformation, and false conspiracies, along with all the outrage surrounding them.

Instead, Zuckerberg saw Facebook as having a “reputational and a partner issue.” Since the boycott makes up a small portion of the overall revenue, the defiant CEO says, “We’re not gonna change our policies or approach on anything because of a threat to a small percent of our revenue, or to any percent of our revenue.”

But then, maybe Zuckerberg has finally had enough and will describe a list of new features for labeling fake news and disinformation. On our Facebook app, we may finally see warning labels on bad content before reading it, just like a food label tells you how much sodium is in that pack of Cheetos before you wolf it down. Maybe a tone-deaf CEO is finally regaining some of his hearing?

4) What Else Are You Not Telling Me?

Big Tech may or may not be broken up by regulators out of the current hearing. But what is clear is that AI algorithms by tech giants shouldn’t be opaque and unquestioned. Financial audit, for instance, has been a means of providing the public with assurances of a company’s integrity in its financial reports, without disclosing proprietary information and sensitive processes. Lawmakers might consider creating a new class of specialists—data science auditors—whose job would be to conduct algorithm audits to ensure any automatic decisions are unbiased and ethical.

Businesspeople have long despised politics, while lawmakers have scant regard for product marketing. 2020 is proving to change all that. The historical divide between the two worlds is now coming together. Our future technologies depend on it.

Originally published on Forbes

Outlast your competition and thrive in an ever-changing world

In Leap, Howard Yu, LEGO professor of strategy and innovation at IMD, explains how companies can prosper, not just survive. Leap identifies five fundamental principles that allow companies to stay successful in the face of such competition.

The post Four Top Tech CEOs Testify In Washington Now. Here’s How This May Affect Your Tech Life appeared first on Howard Yu.

July 16, 2020

Netflix Is Managing Expectations While Winning The Streaming War

“Under promise, over deliver”—this is ageless wisdom in managing expectations of the financial market and it seems to be Netflix’s strategy. Yesterday Netflix announced it has added more than 10 million subscribers in the three…

The post Netflix Is Managing Expectations While Winning The Streaming War appeared first on Howard Yu.

June 28, 2020

Why Some Retailers Are Thriving Amid Disruption

Retailers that successfully adapt to the pandemic’s social-distancing requirements offer a model for making a quick digital pivot.

A crisis reveals as much as it devastates. Retailers that were struggling before the coronavirus outbreak are…

The post Why Some Retailers Are Thriving Amid Disruption appeared first on Howard Yu.