Howard Yu's Blog, page 4

January 18, 2021

How Complexity Kills a Company and How to Sidestep It

Here’s how a corporate death spiral begins. The first act begins with the product team. Its goal is to keep offerings attractive in the market. But in its daily work, many of its processes are manual, complex, poorly documented, and incredibly fragile. There are many workarounds. Managers are relying on quick fixes. Time is never enough.

Act two. A competitor or a new startup dreams up a new offering. Someone high up in the company makes a bold promise that dazzles investors. Now the product team is tasked with an urgent project. They need to deliver a set of new product features.

Employees then discover that the new web page can’t be fully integrated with the inventory system. This, in turn, impacts the existing workflow built by the Quality Assurance department. Failing that step of checking violates another rule set by the Finance department. There are numerous conflicting demands. People are bypassing standard operating procedures in order to “get things done.” This sets the stage for the third and final act.

A steering committee steps in to arbitrate conflicts. The product team is told to freeze its requirements so that IT and manufacturing can move into production. Everyone works overtime to communicate, coordinate, and get approvals. The press release is being drafted for the imminent product launch.

The product finally hits the shelves. But the market responds with a yawn. The hype fades away as quickly as it arrived.

There are many reasons for the lukewarm response. There are some missing displays in the retail stores. There is an IT outage during the peak hours of website traffic. There is some confusion over the pricing promotion created by the sales team. Then there’s the suspicion from consumers that the product packaging has not been well designed.

In the “after-action review,” the management team concludes that it’s an execution problem. We need to have better alignment, they say. The market, meanwhile, is moving on to the next big thing. The product team has a new idea…

The question is obvious: How can you get out of this cycle?

Why large companies struggle with growthThe scenario above is commonplace. It’s especially common within large, traditional companies. Managers are often working within tightly coupled, monolithic business units. Organizational handoffs—from R&D to manufacturing to marketing to customer support—rely on face-to-face coordination and email chains. They require multiple approvals. The product development cycle is long. The production ramp-up is longer still.

These managers would have a hard time precisely mapping out the end-to-end workflow. Even top executives would have trouble “connecting the dots” across the company. No one knows exactly what’s happening daily. All they have is a vague idea. Operating manuals scatter. And if people spend a month or two drawing up a comprehensive map, it probably looks like this.

A common workflow inside a large company

The organization is complex with complicated decision-making. It confuses everyone. An organization of this nature can only execute the most routine tasks. But even doing that is stretching the company’s limits because the system is error-prone. Everyone seems to be in a constant state of exhaustion. People find it almost impossible to find time to think. Innovation is a luxury.

You may think tech companies are immune to such complexity. Some may think companies that move “digital bits” without delivering “physical atoms” always have a simpler existence. But that’s simply untrue.

Google, Facebook, LinkedIn, Netflix, eBay, Twitter, and Etsy all went through near-death experiences. Virtually all tech startups began with a tightly coupled system in a single code base. Even Amazon started in 1996 as a single application. It ran through a web server that talked to a database on the back end. Over time, these startups all sprawled into monolithic architectures comprising millions of lines of code.

You can’t grow further with these enormous architectures where all the functionalities are sitting within one application. So these companies had to break it up. They turned the entire IT infrastructure into tens of thousands of microservices. These microservices could then exist as independent, decentralized modules that had standard interfaces with other modules. Let me make this more concrete.

Breaking down a complex IT system into simpler partsHistorically, software developers have been responsible for app features. Meanwhile, IT operations have been responsible for testing sites and the actual production environment on the computer servers. It’s natural that app developers would coordinate with IT operations. They would coordinate the testing schedule, feature launches, and troubleshooting. And all the intricate processes and dependencies have lived in people’s heads.

The survivors in the IT sectors are the ones who rebuild the organization from the ground up. There is no escape. They simply bite the bullet before time runs out. They do so by keeping all the pre-existing IT functions unchanged. But the input and output of each function get standardized. Communications between different teams are made through APIs (application programming interfaces). This means less ad hoc email and fewer manual Excel spreadsheets.

Now, the format of the requests between app developers and IT operations becomes consistent. The next step is to automate those routine coordinations. All of a sudden, app developers can run production-like environments on their own laptops. People can create, on-demand, the testing environment that developers need via self-services. The role of IT operations changes too. IT is not responsible for manual coordination. They no longer push code manually to the actual production. Instead, they focus on designing a better, faster production environment. In other words, app development and IT operations are decoupled.

Now hold that concept and port it over to a manufacturing setting.

Manufacturing organizations with agilityConsider a traditional manufacturer. Its centralized manufacturing plant shares a radical idea with the other five different product groups. There will be no more product launch meetings. Instead, all the factories will make their production schedules transparent, daily. Product groups can upload their requirements online. The manufacturing plants will then display when the required capacity is available. The online system will show whether they can meet the requirements. And if it is impossible to ramp up production fast enough, any product group is free to negotiate with other external contract manufacturers. The system even shows detailed contact information of these external parties.

No more email. Everything is done via a service platform that looks like Apple App Store.

Now you ask, am I dreaming? This can’t possibly be done, some may say. But there are companies that have already done so or have already moved very far in that direction. And not just digital natives, like Netflix. It’s not just Amazon, either.

Haier Group—one of the world’s biggest home appliance manufacturers—is one example of a company that has taken this approach. For years, the China-based Haier has organized itself as a swarm of self-managing business units. Haier has some 4,000 microenterprises (MEs). Each comprises just 10 to 15 employees. Instead of being centrally orchestrated, these MEs independently transact with one another. They are given full autonomy to deliver the final product to consumers. Certain MEs manufacture specific component parts; others provide services like HR or product design. Coordination is managed through internal platforms, making the idea comparable to an app store.

What Haier has pursued is a modular organization. Its architecture is loosely coupled with well-encapsulated units. No more monolithic businesses. Since the interfaces across these MEs are highly standardized, automating information exchanges becomes possible.

In such settings, managers can request services without face-to-face meetings. No email. No phone call. Just one click away. There is no need for project planning sketching beyond the next three months. You can even get rid of project escalations because no one is holding you back except yourself.

Each team is small and self-contained. If there’s a failure, it won’t cause global disruption. That’s system resilience. Remember, a big organization is brittle unless you break the monolithic system into tiny units.

How to jumpstart simplicityAll these benefits may seem like something from the distant future for most of us. You and I are probably not working at Netflix or Haier. But the seed of a movement is always in your hand. Think, for example:

In your immediate team’s regular work, can you identify standard, routine work versus work that is nonstandard? The Pareto principle suggests that 80% of your department’s time is spent doing routine tasks, while 20% is not. For that 80%, do you have a clear picture of your department’s information flow? Think about the inputs and outputs.Once you have a full picture of how these routines work, identity opportunities for simplification. Can you make information transparent to other departments and transmit it through a self-service? Are there process steps that make no sense? To what extent can these routine tasks be outsourced or even automated? Your aim is to eliminate those annoying emails and telephone calls that get in your way every day.What you are doing is no mere housecleaning. You are disciplining yourself to pay down the coordination debt of your organization. If you don’t, the workflow complexity will explode like compound interest as your company’s scope of work increases.

Most of us are not working at Haier or Netflix. But the benefit of using these techniques, however imperfectly, is to preserve our own sanity. High quality and large quantities of work will always be demanded from your team. But everyone deserves to have a life outside of work. To achieve that, you need to pay down the coordination debt.

Stay healthy,

P.S., Does your company struggle with complexity? Have you observed good practices that overcome such struggles? Let me know what you think. Join our discussion below.

The post How Complexity Kills a Company and How to Sidestep It appeared first on Howard Yu.

January 13, 2021

One Chart Explains Who Loses the Most When Trump Delists Chinese Companies

The tension between the outgoing president and China is hurting an unlikely bystander: the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). On New Year’s Eve, the NYSE said it would delist three Chinese telecom stocks to comply with Mr. Trump’s executive order. It then reversed course four days later, saying that it wouldn’t. Then it came back again, saying it was, in fact, delisting China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom.

Delisting a stock means removing it from where it’s been traded. US investors will be barred from making new purchases in these companies. Reuters yesterday reported that Trump was also considering removing Alibaba and Tencent during his final days at the White House.

Targeting these two tech giants would cement Trump’s “tough on China” legacy. About $1 trillion of Chinese internet and tech stocks are held by US investors, according to Goldman Sachs estimates.

The reason for such enormous holdings is simple: American investors want to participate in China’s growth story. Your pension fund is likely to have invested in some Chinese firms, including Alibaba and Tencent, as a diversified portfolio. They have grown much faster than companies from other emerging markets.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index, an index that tracks market performance in 26 countries, shows exactly how China has risen to a dominant position.

Whatever the eventual outcome, the biggest damage suffered due to this double U-turn delisting has been to the reputation of New York City—the financial capital of the world. The whole process has been chaotic and opaque.

As for institutional investors, including pension funds, they might wonder if China’s oil majors and banks will be the next targets. Taking part in the world’s second-largest economy is a must for any high-net-worth individual, so they might end up looking into other means of investment rather than keeping their trades in New York City.

I joined Cheddar TV 📺 from the New York Stock Exchange earlier to discuss if the tension between US and China will continue into the Biden presidency. So much has happened in the last few days. You can watch it here 👇

Stay healthy,

This article is co-authored with Angelo Boutalikakis, a research associate at the LEAP Readiness Project.

The post One Chart Explains Who Loses the Most When Trump Delists Chinese Companies appeared first on Howard Yu.

January 11, 2021

What Does It Mean if Your Company Expects Failures, Positively?

Big tech spends big. And Amazon spends the most. A fearless Jeff Bezos plows money into warehouses and data centers in the face of uncertainties. Last May, he warned an audience of investors to “take a seat,” because “we’re not thinking small.” He told them that Amazon would invest all of its $4 billion operating profits to capture the entire rise of e-commerce because of COVID-19.

It’s been a gambit well played. This past holiday season saw a 73% jump in e-commerce from the previous five-year average.

Amazon is likely to account for more than 8% of all U.S. retail in 2020. It will no longer be a “low single-digit percentage,” an argument previously used to dodge antitrust probes in the U.S. and Europe. Of course, there’s never been an antitrust case that defines a product market as insanely broad as all retail in America. It’s as if United Airlines called itself tiny by stating its market share out of all transport, not just aviation. But even with this insane argument, Amazon can’t hide its size any longer.

The more Amazon grows, the more it spends. The more it spends, the bigger the risk of failures. And that’s by design. “We need big failures if we’re going to move the needle—billion-dollar scale failures,” Bezos wrote. “And if we’re not, we’re not swinging hard enough.”

I know you are rolling your eyes. Another bit of Bezos’s soaring rhetoric.

But Amazon is in fact the biggest spender on infrastructure investment, according to a recent report by The Information. It’s not just bluff.

Capital expenditures—or capex—are the funds businesses spend on mostly physical assets, from the building and outfitting of offices to manufacturing equipment to the computers and software needed to operate their services. The most striking spending increase came from Amazon, which put it far ahead of Alphabet. The parent company of Google, Alphabet has been, until now, the champion of capital spending.

Capital expenditures—or capex—are the funds businesses spend on mostly physical assets, from the building and outfitting of offices to manufacturing equipment to the computers and software needed to operate their services. The most striking spending increase came from Amazon, which put it far ahead of Alphabet. The parent company of Google, Alphabet has been, until now, the champion of capital spending.

Amazon’s high spending on backend operations like data centers, warehouses, sorting centers, and delivery stations doesn’t shield the company from commercial failure. Behind the success of AWS, Kindle, Prime, and Alexa, there are more embarrassments than we can recall. Here’s a small sample of the long list of failures.

1. Fire Phone (2014)

The phone had a series of cameras to simulate a 3D screen and could change its image as the user moved it. This might have been a neat party trick, but it could hardly be called a killer app. Amazon wrote off some $170 million in inventory and stopped selling it for good.

2. Destinations (2015)

Seeing how Airbnb was taking over travel, Amazon tried creating close-to-home vacations. The site featured getaways and hotels within a customer’s driving distance. It’s an interesting concept that didn’t fly. In less than six months, Amazon shut down Destinations.

3. Restaurants (2015)

It wasn’t blind to food delivery service either. Amazon delivered restaurant meals to Prime members for almost four years in more than 20 U.S. cities. Still, it couldn’t bite off growth from Uber Eats, Grubhub, and DoorDash. So Amazon Restaurants got shuttered.

4. Daily Dish (2016)

But what about more specialized services? Like workplace lunch delivery? Amazon tried that too. Daily Dish let employees at specific companies order lunch specials for delivery to their offices. People received daily menus via text message and placed their orders on the Prime Now app. That didn’t work; it was shut down.

5. Amazon Local (2011)

Remember Groupon and Living Social? Daily deals were big. So Amazon started its own program, Amazon Local, in June 2011, right in the middle of the Groupon peak. The project ended as quickly as the daily deal fad faded away.

6. Pop-up Stores (2018)

These pop-up shops typically occupied a few hundred square feet of space in malls, Kohls, and Whole Foods. They featured staff, dressed casually in black Amazon T-shirts, who encouraged passersby to try out voice-assistant speakers, tablets, and Kindle e-readers. Then, a year later, it shut down all 87 of its U.S. pop-up stores.

7. Wallet (2015)

The reason that Amazon doesn’t have a consumer-facing wallet like Apple Pay or Google Wallet is not for lack of trying. But its dominance over e-commerce doesn’t translate into a real advantage in digital payment services. After giving it a six-month shot, Amazon killed its mobile wallet, leaving the fight to Apple and Google.

I think you get the idea. Winning offerings rarely succeed from day one. The trick is to apply what you’ve learned and try again.

When Amazon’s foray into Fire Phone came crashing down, Bezos publicly took personal responsibility. The team quickly learned that it was wrong to design a phone with its biggest selling point being making shopping on Amazon easier. Adding to consumer skepticism was the small number of third-party apps.

At Lab126, Amazon’s hardware R&D, Bezos told employees not to feel bad. Managers instead applied the lessons learned to the launch of Amazon Echo. From the outset, the Echo team sped up the certification of third-party apps, or “skills.” This made Alexa ubiquitous, not only found on the Echo Wi-Fi speakers but also inside BMW and Ford, Sonos and Bose, Philips lighting and GE appliances.

Every failure at Amazon is announced by a standard press release: We’ve learned a great deal from [this failed project X] and will look for ways to apply these lessons in the future as we continue to innovate on behalf of our customers. You don’t hear about massive overturn of executive teams. There is no exodus of managers en masse upon shutting down of a single project. There are safety measures to retain the precious knowledge gained from failed ventures.

And so, here are the assumptions under which Amazon operates:

1. Most innovation efforts will fail, but we need to capture the lessons learned systemically. That includes documenting how and why that failure happened and retaining key managers who took calculated risks but failed. Don’t fire your best students after they’ve learned their lessons.

Does your company fire people over things that they can’t control?

2. Don’t promise investors your new innovation will work out. Financial projections on radical innovation rarely pan out. Show them instead the tractions that you’ve already achieved.

Does your company overpromise its innovation efforts to the financial market?

3. The eventual success of an idea requires many rounds of restarts. Be prepared to cut your losses quickly and restart the project afresh. Don’t throw good money after bad.

Can people at your company shut down a project easily? If not, why not?

4. And just because you have tried something in the past, doesn’t mean that it will never work. A failure can have many causes. The same concept can take off amazingly once it’s found the right timing and the correct format.

Does your company persist in experimentation?

If your answers are “yes” to all four, congratulations! Stay on course doing what you’ve been doing. If your answers are less positive, try to create an environment for at least your own team so that your people and your team members can flourish.

The world is never perfect, but you always have some degree of control. If innovation is your passion, those are the four areas you can focus on to influence what matters the most.

Stay healthy,

P.S. What are your experiences and observations in corporate innovation? Share with us your thoughts on those four questions above.

The post What Does It Mean if Your Company Expects Failures, Positively? appeared first on Howard Yu.

January 6, 2021

Two Charts That Explain Why Alibaba and Jack Ma Are in Trouble

Chinese big tech is in trouble these days. And it’s not only because of Trump.

The White House signed another executive order this week. It’ll ban Alibaba’s Alipay, Tencent’s QQ Wallet and WeChat Pay, and six other Chinese apps in the US. But the real trouble is at home. Beijing is cracking down on them too.

The Chinese government has drafted antitrust rules aimed at curbing monopolistic behaviors by its giant internet platforms. It suspended the initial public offering of Ant Group, which could have been the world’s largest-ever IPO . Then Jack Ma disappeared.

Between December 24th and 28th, Alibaba’s valuation fell by 13%, or $91bn. This happened despite the $6bn in share buy-backs aiming to avert the slide. The decline in Alibaba’s share price also weighed on other internet and technology companies. Games publisher and dominant social network operator Tencent Holdings and e-commerce giant JD.com felt the heat too.

Chinese authorities have reputation for supporting national champions. Think about the alleged support that Huawei and TikTok have received. Then there is the forced technology transfer that Western companies have constantly complained about. Now, all of the sudden, Beijing has decided to rein in its own tech giants. Why?

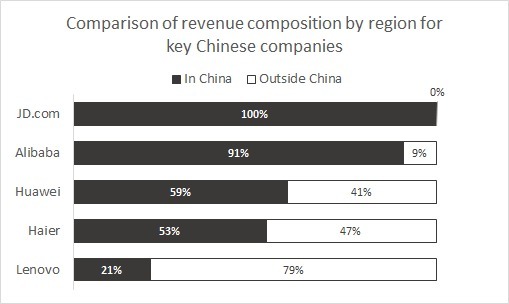

Here is a revenue breakdown of the five leading companies in China.

JD.com and Alibaba are under extreme scrutiny. We haven’t heard of crackdowns against Huawei, Haier or Lenovo. Companies that have substantial overseas revenues are immune.

Here is another picture. It looks at user volume among the three major platforms.

Again, it is WeChat and Alibaba being scrutinized. TikTok remains free as far as Beijing is concerned.

What’s emerging here is that the companies still receiving government supports are ones that have already gone international. These companies earn foreign money and bring home profits. The reason why China’s big tech companies are falling out of favor is simple: They are disrupting state-owned enterprises without winning abroad.

I gave an interview about this point on Bloomberg TV this week. You can watch the TV segment here.

So what are the long-term implications? Alibaba and Tencent will speed up their plans to go abroad. Chinese big tech will survive. But to serve the national interest, it will have to expand internationally, very quickly.

Stay healthy,

The post Two Charts That Explain Why Alibaba and Jack Ma Are in Trouble appeared first on Howard Yu.

January 4, 2021

You Have Your New Year’s Resolution, But Have You Prioritized Enough?

The afterglow of the holidays will fade by end of this week. The to-do list will grow longer. You still have your New Year’s resolution in mind. But instead of pushing back and pausing, you feel the need to rush in.

Don’t.

Your resolution should not be to do more. It should not be about sticking to the schedule. It should be about shortening what you would have written down. Do less. Make space for the essentials. You’ll end up working just as hard, but instead you’ll work on what truly matters.

Here’s one way to prioritize at work: think leverage.

Andy Grove, the legendary former chief executive and chairman of Intel, once described the productivity of a manager this way:

A manager’s output = the output of her organization + the output of the neighboring organizations under her influence

Say you want to increase the output of your organization. You can try to speed up your own work. That’s likely to lead to burnout, like what you remember from 2020. Or you can increase your managerial leverage.

You know that you are engaging in high-leverage activities when:

many people are affected by your presence, or

a person’s behavior has been changed over a long time by one brief encounter with you.

That’s why Grove believed that “training is, quite simply, one of the highest-leverage activities a manager can perform.” He said:

“Consider for a moment the possibility of your putting on a series of four lectures for members of your department. Let’s count on three hours of preparation for each hour of course time—twelve hours of work in total. Say that you have ten students in your class.

“Next year they will work a total of about twenty thousand hours for your organization. If your training efforts result in a 1% improvement in your subordinates’ performance, your company will gain the equivalent of two hundred hours of work as the result of the expenditure of your twelve hours.”

Grove was an engineer, so you’ve got to trust his math. Trust me, he made Intel deliver microprocessors with doubling computing power every eighteen months. Ticktock, ticktock. Like clockwork.

Here’s another consequence when you spend time training your own people: you get to delegate more with trust. That’s just another way to increase your leverage further still.

Now you ask, “How can I increase the output of the neighboring organizations?” Grove recommended supplying them with a unique key piece of knowledge or information. This can happen more easily than you think. Here’s an example.

I teach executive programs at IMD Business School. Due to COVID-19, programs went online. Program directors like me were tasked with developing new curricula, so we’ve launched a bunch. Now there’s this unjustified belief that professors are know-it-alls. So we are often left alone to “innovate.”

But here are the people who, in fact, can make data-driven suggestions to professors—the very quiet team that’s responsible for implementing our post-program surveys.

They are ones who can spot any emerging trend of what works and what doesn’t across the entire school’s portfolio, whereas professors are making wild guesses based on individual observations. All professors are trying to predict what can make an online program work, without seeing the full picture.

Put another way, a summary report given by the survey team can quickly change the day-to-day practice of dozens of professors. That’s leverage.

Think about your own work. You could be in accounting, legal, IT, HR, marketing, sales, production, or R&D. Are there insights that you can easily find out and share that will tremendously raise the productivity of others?

Adam Grant from Wharton has shown that being a giver—with no strings attached—is the best strategy when it comes to being successful in business and in life. Andy Grove is no academic, but he did what came intuitively and made it a discipline. What he practiced is highly leveraged giving—giving training, giving unique advice. Give what you can do easily, but make sure it will give others enormous value.

So in 2021, do less. Focus more on highly leveraged activities for this new year.

Stay healthy,

P.S., What’s your achievable New Year’s resolution for 2021? Any tricks that you use to make real and lasting changes? Join our discussion below.

This article is first published at Forbes.

The post You Have Your New Year’s Resolution, But Have You Prioritized Enough? appeared first on Howard Yu.

December 29, 2020

Tech Giants Are Monopolies, But How Far Could They Go? Look To China

Everyone makes predictions. It’s a sport that’s especially tempting as 2021 dawns. Will the market crash? Are there wars looming? Will tech giants get even bigger?

No one raised an eyebrow when Mark Zuckerberg bought tiny Instagram in 2012 for $1 billion. Lately, regulators want to unwind the deal, as well as the one for WhatsApp, which might well spell the disintegration of the Facebook empire in 2021.

But this is not only about Facebook, or Amazon, Google, or Apple. It is a global shift of the boundaries within which monopolies can function. Here is a prediction: 2021 will be a year that will unwind the “data advantages” among tech giants.

How big tech is cornering markets

Datasets become exponentially more valuable when you combine them. When Google introduced Gmail, it built a new dataset of people’s identities. In addition to the existing search engine dataset, Google then also had people’s email addresses and IPs. As a result, Google’s AdWords can now provide more refined targeting for advertisers.

The same happened with Google Maps. When Google tied people’s identities and purchase intent to their geo-locations, advertisements became even more accurately targeted to consumers.

In today’s economy, this ability to predict behavior, curate offerings, and fulfil orders automatically offers the single most important advantage: helping an organization expand. Sure, the initial entrepreneurial insights are still important — discovering your customer’s needs is the first step. But once you have a minimally viable product, your ability to scale determines your success.

That’s why tech giants have been snapping up start-ups — buying other businesses has been an important route to growth. It’s been harder for entrepreneurs to stay independent, and IPOs have been on the decline.

But what we see now is tech giants being blocked from buying up small firms.

The US Justice Department recently blocked Visa from buying Plaid, which provides payment processes and works in a similar way to Stripe. Plaid provides the plumbing that lets apps like Venmo, a cash transfer service, or Robinhood, a stock trading platform, access user bank accounts.

Today, Plaid acts as a link between fintech apps and some 11,000 financial institutions. Visa and Mastercard aid in electronic fund transfers between bank accounts, but Plaid can take out these middle men. One day, consumers might make purchases without a debit or credit card, paying merchants directly from their bank accounts. That’s why Visa wants Plaid — it can’t afford to miss the next big thing.

Regulators worry that an acquisition could “deprive American merchants and consumers of this innovative alternative to Visa.” This change in attitude indicates that companies may no longer be able to simply buy out their competition. Many regulators globally have broadened their field of view, and “consumer welfare” has a wider scope. Regulation seems to indicate that pricing is no longer the only consideration. Instead, there has been a shift towards protecting a competitive marketplace.

The aim is to prevent the concentration of industrial power, because too much concentration always leads to systemic risks. This is what happened in China.

China leads the charge to stricter regulation

Just hours before the launch of Ant Group’s mega IPO, Chinese authorities cited “major issues” with the company. The release of the US$300 billion fintech disruptor’s IPO has now been put on pause.

At the heart of Ant Group is a product called Alipay, created by Alibaba in 2004 as a payment tool for its online marketplaces. Alibaba then went into financial services, such as lending, wealth management, and insurance, all of which were offered through Alipay. Like all things in China, Ant Group’s growth has been epic.

And that’s why regulators have started to worry. As Ant Group underwrites loans, it relies not on human credit officers, but on algorithms. The data fed into those algorithms reflect the long boom of China’s economy. There’s likely no downturn in the model. There has been no Black Swan event in China. The skewed set of historical data, combined with Ant Group’s reach, can pose a systemic risk for the entire country. This is the problem with the concentration of industrial power.

Tech giants are led by human CEOs, and they may not always know all the systemic risks they have created outside their own enterprise. The only way to prevent a catastrophic outcome is to limit the size and reach of a company.

Regulators are now trying to do just that. No one is saying Amazon is monopolizing retail. It is not. Its revenue is still smaller than Walmart’s. No one is saying Amazon is charging prices that are too high and hurting consumers. But regulators are saying Amazon’s own rules are unfair to its third-party merchants who sell through Amazon.com.

Similarly, Facebook has competition like TikTok. But regulators are unhappy that Facebook is leveraging its userbase and information. When it quickly copies Snapchat’s features in order to destroy a competitor, the game doesn’t look fair.

Where do we go from here?

In each of these examples, it’s not only the market share won by the tech giants that’s causing concern. It’s also the ease with which a company can cut across all verticals and use its data advantage to overwhelm competition. What might result from this is that tech giants may simply be barred from entering certain sectors, such as healthcare, finance, and transport, entirely.

It wouldn’t be the first time. The reason AT&T didn’t participate in the computer business was not for a lack of technology — it had been prohibited from doing so in a 1956 agreement after the company was deemed a “natural monopoly.” Until it was broken up in 1984, AT&T had been barred from entering the computer business.

What can come out of banning large companies from entire sectors? We can protect and make space for progression and development. Regulators can help to create a level playing field, giving new players a chance, and stopping larger companies from becoming such enormous monopolies that their self-preservation hinders progression — which will benefit us all.

And if this prediction turns out to be true in 2021, we are called to be optimistic after the gruesome year of 2020.

Stay healthy,

P.S., What are your predictions about big tech in the coming year? Will you see governments reining companies in? Share your thoughts with us.

An earlier version of this piece was coauthored with Angelo Boutalikakis and published by The Conversation.

The post Tech Giants Are Monopolies, But How Far Could They Go? Look To China appeared first on Howard Yu.

December 17, 2020

How To Understand The Biggest IPO Of 2020

The strange year of 2020 is even stranger when Airbnb went public. Its initial public offering has become the largest IPO of the year. When travel and hospitality are being hit the hardest, investors all want a piece of Airbnb. How could it be?

Listen to my interviews with the BBC and Bloomberg Radio.

December 10, 2020

Is Airbnb’s IPO listing this week worth your investment?

The travel experience company has its fair share of knocks this year, but it has some solid fundamentals.

Two of the most anticipated IPOs are rounding out 2020. Airbnb and DoorDash are making to make their initial public offerings this week.

Both companies represent the future – one in the travel experience and the other in food delivery.

Arguably, DoorDash got a boost because of COVID-19, while Airbnb has taken a hit. That hit had been reflected in the company’s valuation which fell from a peak of US$38 billion in 2019 to US$18 billion earlier this year.

Even though Airbnb restored profitability by the third quarter, when it was reported that Airbnb’s IPO would value the company at US$42 billion, it raised the obvious question: Is it worth the price?

The short answer is yes. Because Airbnb is the Amazon of travel. COVID-19 is to the hospitality industry in 2020 as the dot-com bubble was to the Internet in 2000. Jeff Bezos emerged from the crisis stronger than ever. So will Brian Chesky – co-founder and CEO of Airbnb.

It’s the inherent strength of its operations that Airbnb will roar back before anyone else in the industry.

GLOBAL NETWORK EFFECT

The importance of network effects on platforms is well-known. Whether you are Uber, Airbnb, DoorDash, or Grab, being big gets you bigger. The more drivers there are on Uber, the more riders it will attract, and vice versa.

But the difference is that most platforms are confined within a local network. Drivers in Singapore care mostly about the number of riders in Singapore, and riders in Singapore care mostly about drivers in Singapore.

Contrast this with Airbnb. A New Yorker cares little about the number of Airbnb hosts in New York City; instead, they care about how many there are in the cities they plan to visit. That means Airbnb’s network has been global from day one.

Any copycat competitor would have to enter the market on a global scale. That’s a far harder thing to do. That’s why you see lots of competition in food delivery and ridesharing, but almost no one copying Airbnb. The company offers listings in over 190 countries today.

A NICE MONOPOLY

That global network effect will translate into a “natural monopoly.” Airbnb can easily be seen as a bad player. After all, its global supply boasts over 7 million listings worldwide.

That’s more than Marriott International, Hilton Worldwide, InterContinental Hotels Group, Wyndham Hotel Group, and Hyatt Hotels combined.

But the co-founders of Airbnb – Chesky, Nate Blecharczyk and Joe Gebbia – are nice, low-key, friendly people. They have avoided the public and private confrontations and scandals of other CEOs like Uber’s Travis Kalanick and WeWork’s Adam Neumann.

And the best way to avoid anti-trust sentiment is to gather public trust and stakeholders’ approval. Chesky showers the company’s host community with profit-sharing benefits.

Airbnb has created a new “host endowment” and allotted 9.2 million shares to fund it. The endowment may fund grants for educational workshops or annual pay-outs to groups of hosts.

The company has also created a host advisory board, 15 VIP Airbnb hosts whose input is heard by the management team. Chesky promises this advisory board will be “as diverse as the host community itself”, with a fair proportion of women and hosts outside the US.

Just pause for a second. Can you imagine Uber ever creating an advisory board comprising its drivers?

Facebook has finally set up an ethics board – a high-powered 20-person oversights panel of thought leaders and eminent personalities that includes former Danish prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt and Yemeni Nobel Prize winner Tawakkol Karman. But it was done 15 years after its founding.

FUTURE-READY

All companies experience crises, so minimizing mistakes is not the right approach; learning from them is. Airbnb is moving fast to mend things.

When hosts were horrified at their apartments being trashed by partygoers, Airbnb rolled out insurance policies at no additional cost. When COVID-19 continued to rage, it pulled the plug on parties altogether.

But Airbnb isn’t only moving fast in areas that need mitigation. It’s also a company obsessed with constant innovation.

There are experiments like the Backyard initiative, a project that devises fresh ways to design and build shared homes. Then there are big winners like “tours and events.”

And in today’s environment, there’s Online Experience. You can learn to “Dance Like a K-pop Star” live with a local guide in South Korea. Or you can take part in “Cooking with a Moroccan Family.” There’s even a “Day in the Life of a Shark Scientist” from South Africa.

Airbnb probably makes little money from all these. The average price per person is about US$10, and you might pay as little as US$2. But that’s beside the point. For every dollar it saves by not paying for ads on Google and Facebook, Airbnb is investing in differentiation.

Today people are not traveling, but they are reminded of their yearnings. Want to visit Alaska and go salmon fishing? Want to visit Italy and do a wine tasting?

Now, you ask, who in the travel industry will be ready to consolidate everyone else when demand comes back?

The winner will be a franchise that is asset-light and scalable. It won’t be a franchise that squeezes suppliers to death. It won’t be a franchise that sells your attention to the highest-bidding advertiser.

When hotel chains have to thrive for a level of standardization, Airbnb’s varying listings will always be quirky and unique. It’ll be one that’s loved by customers and its community.

A KIND OF ITS OWN

Given all these factors, it’s no wonder analysts might struggle to nail down “comparable” competitors for pricing evaluation. The closest ones could be the online travel agencies (OTAs): Expedia and Booking.com.

But OTAs pay their way to growth. They grow by acquisitions. Booking.com bought Priceline.com, KAYAK, Agoda.com, Rentalcars.com, and OpenTable. Expedia bought Pillow, HomeAway, Orbitz, Travelocity, and trivago.

They are also two of the largest spenders on paid ads on Google.

Airbnb did none of that. It slashed its ad spending and saved US$800 million during the pandemic. It generates direct traffic through better customer experience.

In 2019, Booking.com made a booking revenue of US$15 billion. It commands a market capitalization of US$84 billion.

During the same period, Airbnb made US$4.7 billion. Applying the same market cap/revenue ratio would give Airbnb a US$26 billion valuation.

But given the four reasons you saw above, US$35 billion is all too reasonable for a ground-up, innovative, and global model.

Stay healthy,

P.S. What’s your experience with Airbnb? What’s your view on the future of travel? Join the discussion below. Love to hear your view.

An earlier version of this article is co-authored with Angelo Boutalikakis, a research associate at the LEAP Readiness Project. It was published by Channel News Asia in Singapore.

The post Is Airbnb’s IPO listing this week worth your investment? appeared first on Howard Yu.

December 2, 2020

Who’s Ready for Fintech? Here are Three Charts That Explain

Fintech is All the Rage

2020 has been a year for fintech innovation. And the big accelerant has been COVID-19. When people shop at home, electronic payments take off. When people stop visiting banks, they manage their finances online.

Stripe, a payment processing platform, has been a Silicon Valley darling, valued at $36 billion as a startup. The company powers online purchases for clients like Target and Amazon. PayPal and Square have done well too. Their share prices have soared 180% and 89%, respectively.

Then you have the Chinese startups.

Lufax, an online wealth management and lending operation, has filed for a November IPO in New York. The biggest of them all could have been Ant, although its initial public offering (IPO) was suspended on Nov. 3.

Still, China is now home to a $29 trillion mobile payment market. The trend of becoming a cashless society is irreversible. It’s little wonder why every traditional bank these days is touting their innovation efforts in the fintech space.

Who Has a Fighting Chance?

Whether you are JP Morgan Chase or AXA or Mastercard, the competitive landscape is fast changing. What matters are capabilities around robo-advising, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and mobile services. These are capabilities executives have long recognized. Plastic cards, physical branches, human advisors will soon be relics of the past.

The traditional players are not sitting still. They won’t accommodate the new players without some fighting back. But here’s the thing: it’s hard to know which banks or insurers or credit card companies are most ready. It’s hard to say decide who has fully embraced the big trend, since everyone is talking about the same thing in public.

At the Center for Future Readiness at IMD business school, where I am director, we have been tracking companies’ readiness. My research team selected a sample of financial institutes. They then downloaded every annual report available, together with all the transcripts of investors’ earning calls. All these were fed to an algorithm. We wanted to see how companies write about themselves, and how CEOs and CFOs defend themselves during tough questioning by Wall Street analysts. We tracked how things looked over the years.

You may say, don’t CEOs lie, or at least embellish their stories? They may. But they can’t misrepresent the market year after year for decades. And when you compare companies over a long enough time, patterns of difference emerge.

How Digital Is Each Player?

Over the last decade, smart machines have automated tasks that no longer require programmers to set precise rules. Algorithms are forecasting demands, recommending products, detecting fraud, translating languages and much more. But traditional companies can take advantage of these algorithms only when they are fully immersed in natural language analysis, speech generation, and image analysis. They need to be digitally obsessed.

What you can measure is how often companies mention any ideas or concepts related to digital in their annual reports and investors’ calls. You then total the number of these mentions made over the years. Here’s how it looks.

You can see a divergence.

But of course, just because companies are thinking and talking a lot about digital, it doesn’t mean they are meaningfully bringing those innovations into the marketplace. If they spread their investments everywhere, and don’t focus on a few areas, money and resources get wasted.

The only way to win is to generate tremendous momentum toward accomplishing a few things that are truly vital. Without making tough choices, a team ends up making a millimeter of progress in a million directions. And that includes digital.

Are They Focused and Committed?

So we need a second measure. We need to look at how focused and committed companies are. Are they merely open-minded and exploring everywhere? Or are they committed to exploiting a few focused areas to their full potential?

Here’s how it looks when we combine this exploit-explore spectrum with digital on a two-by-two grid.

This is a combined view of how digitally savvy these companies are, and how committed they are to exploiting an opportunity.

Quadrant 1:

They are focused and committed to the digital trend. The exploit new opportunities to their fullest. These are Visa and Mastercard of the world.

Quadrant 2:

Then you have ING. It is digitally savvy, but seems to have difficulties in committing itself to a narrower set of areas. It keeps “exploring.” The danger of this “spray and pray” strategy is that none of the innovation gets scaled very far.

Quadrant 3:

Here is a transition state. These companies are exploring new areas, but they are not yet digitally aware. They are bumping around in the dark.

Quadrant 4:

Then you have companies like AIG and AXA, which still focus in exploiting the old market opportunities. They are trapped in their past success.

How Preparedness Translates Into Resilience

Does any of this matter, you may ask. What stands out is the share price correlation during the COVID-19 pandemic. All three companies in Quadrant 1 are faring far better than the rest. Their share prices have recovered or surpassed the level they were at before the start of the pandemic. These companies rebound faster than others. They are more resilient.

Notice that in our previous analysis, we are only feeding our algorithm with textual description. We only track how companies talk about themselves. It’s a rough gauge of the mindset of these companies. This mindset—a focus on exploiting digital opportunities—has likely translated into sustained investments. And those investments are paying off now. Digital trends are speeding up. Opportunities favor the prepared. The stock market is noticing.

Stay healthy,

The post Who’s Ready for Fintech? Here are Three Charts That Explain appeared first on Howard Yu.

November 19, 2020

How To Think Clearly During The Pandemic? Downplay Your Identity

Opinions. Everyone’s got one. Here is one revelation for me about COVID-19: Your personal opinions can be easily swayed by your identities. We act not on facts—rather, we choose our opinions based on who we think we are.

I remember meeting a European CEO back in June. It was during the pandemic’s summer break. I had just arrived in Europe, flying directly back from Hong Kong. Seeing me wearing a mask, the CEO said, “Ah, I can see that you just came from Asia. Here in Europe, we don’t believe in masks.” Only Asians would wear masks—that’s what he was saying.

It seems impossible these days to talk with people on matters we disagree about. It’s stressful to have political conversations. Anything becomes nonnegotiable the moment it touches politics.

But as much as you might feel the need to defend your position, you must avoid making choices based on identities alone. Doing so would mean outsourcing your thinking. You will ultimately lose your ability to think freely. Let’s consider exactly how an issue is divided along party lines.

The Random Evolution of Political Parties in Picking Issues

In the U.S., the left-wing liberals, young progressives, and the college-educated population generally aim to challenge the status quo of society. They do so to bring about equality and elevate the standard of living for all. Conservatives, in contrast, respect tradition, support religious morality, and often harbor an aversion to rapid change.

One would think, then, logically, that conservatives would care far more about the conservation of the old ecological order. They should be passionate about protecting ancestral lands, forests, and rivers. But they aren’t. Texas has much weaker environmental regulations than Vermont. Averting environmental change is a left-wing agenda. The issue of climate change galvanizes today’s progressives.

You are right to suspect that these party lines are a bit arbitrary.

We are now so used to our current political setting that we forget it was the late Republican president George H.W. Bush who started the National Climate Assessment. “Those who think we are powerless to do anything about the greenhouse effect forget about the ‘White House effect,’” Bush said in a 1988 campaign speech. “As president, I intend to do something about it.”

But climate change got publicized by Al Gore. Gore’s movie—An Inconvenient Truth—became a global blockbuster. The Democratic vice-president had become the spokesperson for climate change. To Republicans, the conclusion was inevitable: if Al Gore becomes attached to a cause, that cause must be fought against.

Such are the historical quirks. But once the party lines were drawn, conservatives and liberals escalated their own commitment. The liberals started yelling that the sky was falling. The conservatives plugged their ears to the available facts. This is the outcome when an issue becomes “political.” Whomever you root for represents you, and when they win, you win. You need to prove that you are better than the other side.

But don’t forget that, despite all the emotions, the political process underneath is quite random. Issues get attached to a party by chance.

Of course, personally, you don’t feel it that way. You think it’s never the party lines that dictate your opinions. After all, you can certainly recite a list of reasons for the position that you’ve taken on various social issues. It just so happens your favorite party thinks the same way as you do. That’s why you choose to vote for them. But is that so?

The Human Bias toward Consistency

Here’s a thought exercise. Say you’re a smoker. The fact that you smoke contradicts your knowledge that smoking can kill. To be consistent in your own thinking, you must quit. Unless you justify smoking. So some will say, “Smoking keeps me thin. Being overweight is a health risk too.” See there? Your brain is the best spin doctor to ensure logical consistency regardless of your position.

Psychologists have long understood the power of consistency in directing human behavior. Humans avoid contradiction. Our minds help us avoid paradoxes.

It works the same way for politics. Right now, you probably want to go back to work or hang out at a bar. But evidence suggests these actions might be dangerous because of COVID-19. Your favorite party may have accidentally picked one side. And it’s all because of some quirks in the political process.

Nonetheless, if you’re a Democrat, you’ll listen to Dr. Anthony Fauci and stay at home. Your logic is intact. Your political choice is consistent with your personal actions. If you’re a Republican, because the party wants to resume economic activities, you’ll listen to Mike Pence. “The right to peacefully assemble is enshrined in the First Amendment of the Constitution,” he said at a Trump rally. Now you also have a solid reason why you should ignore the warnings and not allow the cure to be worse than the disease. Either way, you’re a consistent person.

Notice how consistency is just another form of automatic response. It offers a shortcut through the density of modern life. Once you have picked one side, consistency allows you a very appealing luxury: You don’t have to think seriously anymore. No more expending the mental energy to weigh the pros and cons of an issue anymore. No more sifting through the blizzard of information you encounter every day to identify the relevant facts. All you need to do is to listen to the spin doctor in your mind and rationalize the choices that the political party has given you.

This is why it’s so important to know the identities you hold when interpreting the environment. When you hear or see something, what interpretation do you jump to? Where does that default interpretation come from? When staying consistent with your identities, are you serving someone else’s intentions instead?

To be aware of the reasons behind your reasoning is to increase your chances of having the right response. Self-awareness is the first step toward awakening. The danger is that our opinions on the latest matters are predetermined by our chosen identities. As Sir Joshua Reynolds once warned, “There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labor of thinking.” Let’s not be that way.

Stay healthy,

The post How To Think Clearly During The Pandemic? Downplay Your Identity appeared first on Howard Yu.