Howard Yu's Blog

May 19, 2021

Global Semiconductor Shortages: Here Are The Lessons On Managing Uncertainties

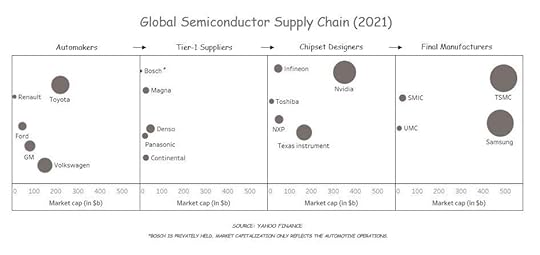

The biggest concern for General Motors and Volkswagen is not the lack of demand from consumers. Demand for new cars is roaring back. But carmakers are stopping their production lines. They are losing hundreds of billions in sales because they don’t have enough semiconductors. Those are the tiny chips at the heart of every electronic gadget.

A modern car can easily have more than 3,000 chips. They control basic features like brakes, doors, airbags, and windshield wipers, all the way up to advanced functions like driver assistance and navigation control.

Early in the pandemic, carmakers signaled to suppliers a decline in their sales forecast. They didn’t see how sales could rebound to their previous peak in the coming years. This is an industry best known for its obsession over manufacturing efficiencies. Everyone has their own version—lean manufacturing, Six Sigma, just-in-time, or business reengineering. Unsold inventories are tantamount to incompetence.

Auto part suppliers, including Bosch and Continental, took in the warnings. They reduced orders from their own vendors. These vendors are car chip producers, who might sound less familiar to most of us—NXP Semiconductors, Infineon, and STMicroelectronics. This very long supply chain would eventually converge toward the great and final contract maker called TSMC.

How TSMC Became the Single Source to Silicon Valley

Many exponential technologies are designed in California, fabricated in Asia. Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Apple all design their own chipsets. But none of them manufacture any. They might buy from Qualcomm or Nvidia or AMD. But these guys all outsource to TSMC in the end.

Few can beat TSMC on semiconductors. Not even Intel. Making a chipset is so complex these days that fabricating it comes down to the last two meaningful players: Taiwan’s TSMC and Korea’s Samsung. The most advanced devices are made using a technology called 5-nanometer node. Five nanometers is about the size of 10 silicon atoms. That’s how our tiny iPhone A14 chipset can contain 11.8 billion transistors. That’s how Apple whips up technology miracles like augmented reality enhanced by the built-in LiDAR sensors with everything connected by the 5G network. What has really been delivering the golden vision of California is the engineering prowess of Asia.

You may ask then, how come other countries haven’t cultivated their own semiconductor industry? Why would they all rely on Taiwan and South Korea? They did try. The US congress is passing a $52 billion investment proposal. China has been lavishing cash on the sector for a very long time. But hard science doesn’t bend because of the whims of politicians. It takes real expertise and persistently deep pockets.

The reality is that TSMC alone plans to spend over $100 billion on R&D and capital expenditure over the next three years. What other company could be so fearless? Intel is planning to spend $20 billion, and they are playing catch-up.

[image error]

The irony is that when carmakers reduced their sales forecast, their suppliers got very nervous. Some invoked clauses in their contracts so that they could cancel the existing chipset orders. They claimed circumstances were beyond their control. The pandemic was akin to natural disasters like earthquakes, they said.

They didn’t need to do that. TSMC happily shifted its manufacturing capacities to other sectors. Outside of automotive, many had increased orders at the beginning of the pandemic: home appliances, mobile phones, personal computers, and healthcare devices.

Only one carmaker stockpiled.

How Toyota Escaped the Competitive Herd

There’s a built-in assumption that carmakers were making. When they slashed orders from suppliers, they assumed that when production ramped back up, chip suppliers would accommodate them.

The problem is that executives from GM, VW, or Ford failed to anticipate the basic dynamics of bargaining power. That’s an observation made clear by Ben Thompson of Stratechery.

When TSMC diverted its manufacturing capabilities from GM or VW to Apple, it could have reverted that decision, at least in theory. But it all depends on who is more important. You don’t need to be an insider to make the right guess. Purchasing volume equals bargaining power. Automotive is nowhere close to an important customer segment to TSMC when compared to other tech giants. When there is a global shortage, the big get to eat first.

The real question to interrogate is this: How could GM and VW, for example, with so much emphasis on “digitalization,” not see this coming? If their CEOs are so adamant about their digital roadmap during their investors’ calls, how could these companies pay no attention to chipset scarcity?

Except for Toyota. This is the company that invented just-in-time manufacturing to eliminate inventory. Now it has stockpiled all the way through the pandemic.

During the last financial crisis, Toyota has created a database that stores supply chain information for around 6,800 parts. Every day, every week, every month, Toyota communicates with thousands of suppliers at all levels. CFO Kenta Kon saw the complete transparency in the supply chain as part of the “rescue system.” This is how Toyota secured “one to four months of stocks as necessary.”

What Allows Smart Executives to Be Productively Paranoid

Most managers find it more attractive to focus on how to win, rather than trying to understand how they could lose. Indeed, most of us spend very little time thinking through alternative scenarios. What if this doesn’t work? What would we do then? What might make this not work?

This is human nature. Unless you have access to data, bringing bad news to an organization can be a career-limiting move. But Intel’s former CEO Andy Grove said, “only the paranoid survive.” What Toyota demonstrates is that you need organizational infrastructure to make productive paranoia possible.

The big consequence is this: in December, VW announced it would stop producing its bestselling brands, including Audi, in factories across Europe, America, and China. It furloughed thousands of workers. All this is not because of the lack of demand. It’s because the part flow from Continental and Bosch has slowed to a trickle. Not enough chipsets.

This is when Toyota wrested back the title as the world’s largest automaker from Volkswagen and safely distanced itself from Nissan, when both have few cars to sell. Toyota topped the industry again not by promising an outsized initiative. Rather, it has been investing in the mundane, in scenario planning, so that it could outsmart others in the long run.

Scenario planning is what smart leaders rely on. Risto Siilasmaa was the former Nokia chairman who had turned a dying company into the world’s third-largest telecom equipment supplier today. He said scenario planning is not just about identifying existing options but about constantly imagining and developing alternatives, then identifying the actions associated with each option. If you were to slash inventories, including chipsets, could you get them back later? What if you couldn’t? What would be the consequences?

The scenario tree is a living, growing organism, Siilasmaa said. “Each time you discuss your findings, you’ll find new sub-branches that need to be explored. New possibilities are constantly revealed, both positive and negative.”

To do this, you need the right mindset, real-time data, the organizational infrastructure for support. As for most of the car guys, chipsets are not like traditional car parts. Car people have paid less attention to them. As an auto executive said, “they don’t know how the sausage gets made at the bottom.”

And when transparency is missing from the supply chain, managers can only go by the book. They do what looks right and proper but is ultimately ineffective. “We expected a very strong recovery after the summer and we expressed that quite clearly to our tier-one suppliers,” said Audi’s procurement chief, Dirk Grosse-Loheide. That’s right. Expressing a viewpoint is all one can do when one is powerless.

This is what happen when an organization cannot plan ahead.

Thanks for reading—and be well.

P.S., What is your favorite technique that you’ve come across related to scenario mapping? What are some of the most helpful conversations you’ve had with your team when successfully navigate uncertainties?

This article has been co-authored with Lawrence Tempel, a researcher at The Center of Future Readiness at IMD.

The post Global Semiconductor Shortages: Here Are The Lessons On Managing Uncertainties appeared first on Howard Yu.

May 12, 2021

How Lazy Thinking Leads to Outdated Values and Causes a Corporate Meltdown

Imagine you’ve spent two decades built up a remarkable organization. It’s small, but beautiful, with about 60 employees in total. The company has always been laser-focused on its service offerings. That’s how you stay ahead of competition.

People were discussing diversity issue. The racial debate got so heated that it threatened to pull the company apart. You, as the CEO, wanted to calm things down. You said employees should not use the company’s internal chat forums to debate societal and political issues. These are tools for people to collaborate, you reasoned. Employees should spend time building bridges, not throwing up walls at work. Politics must stay out. Days later, one third of your workforce resigned. Now concerned customers are calling in.

This company is Basecamp. It makes productivity software for enterprises. For more than a decade, customer service representatives had kept a list of customer names that they found funny. Some in the “Best Names Ever” list were of Asian and African origin. It had been a harmless office joke. But in the year 2021, the tradition looked out of place.

Employees had read the memoir by Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Others looked up the Anti-Defamation League’s “pyramid of hate.” They argued distasteful jokes lay the foundation for racial crimes. Still others applied the logic of “Me and White Supremacy,” written by Layla Saad, saying silence equals active racism.

These books were international bestsellers. The cultural tidal shift was apparent. Except the big boss didn’t get it. CEO Jason Fried closed the thread on the internal forum. At the fateful all-hands meeting, employees were debating the company’s culture. Longtime head of strategy Ryan Singer said, “I strongly disagree we live in a white supremacist culture.” It’s an all-too-familiar remark. Singer said, “Very often, if you express a dissenting view, you get called a Nazi.” CEO Fried responded, “Thank you, Ryan.” That was it. One third of employees quit after the meeting. A decade and a half of trust-building went up in smoke.

How Not to Be Obnoxious

Values change. Society evolves. Humor changes. There are things that we laugh at today that we could not in the past, or vice versa. Emmy Award-winning producer and writer Lorne Michaels was the one who created the first episode of Saturday Night Live (SNL) and is still producing the show.

Nothing he did in the ’70s could be done today, Michaels described. “John Belushi would not be able to play Japanese. Garrett Morris doing ‘News for the Hard of Hearing’ would have been making fun of a handicap.” To Michaels, leadership in his field is the ability to change one’s mind, and to change it quickly enough. “Between the movie Arthur and the movie Arthur 2, alcoholism became a disease, and no one wanted to laugh at drunks anymore. Whereas for two hundred years they laughed at drunks.”

People miss the sensitivity of a cultural shift because they refuse to listen. They stop listening because the underlying message undermines their identity. This is especially tricky when a lot of emphasis is placed on authenticity these days. The idea of authenticity, to some people, seems to be that honesty requires indulging one’s peculiar way of seeing the world. And to change one’s mind is tantamount to a betrayal of “the real you.”

That, of course, is just another way of being stubborn. Marshall Goldsmith said, “Whenever you hear yourself proclaiming that something is just not you, you might want to question your motivation.” He has seen mean bosses continue to be mean because “it wouldn’t be authentic for me to gush over a subordinate’s performance.” Or managers fail to take credit for their fair share, because “I’m just not the self-promotional type.” These are excuses for remaining stuck. It’s often more comfortable to stay the same and to feel proud of it than working your way out to see an issue from the other side.

In other words, intellectual laziness is the root cause.

Each of us, in our own lives, will face a crisis like the one at Basecamp. The stakes may be lower for you. The inability to shift your value system doesn’t need to lead a business to the brink of collapse. What the Basecamp case highlights is that we must avoid an emotional, reactive response. When you are leading a team, an unthinking, semi-automatic reaction won’t do. There are inner struggles you can’t and shouldn’t escape.

Struggling is painful. But that’s the only way to grow.

Melinda Gates’s Struggle With Her Catholic Upbringing

Humans need a sense of uniqueness and a sense of belonging. Lacking belonging, we are purposeless, missing a larger goal. Without our own uniqueness, we don’t feel in control and able to make personal choices. To grow is to have the two forces collide.

Melinda French Gates grew up in Texas, in a Catholic family of four kids. She credited her mom more than anyone else with cultivating her spirituality. Her mother went to Mass five times a week. She regularly went to silent retreats. So when Melinda married Bill and later co-ran the Gates Foundation in Seattle, she saw her philanthropy work clash with her Catholic faith. In Africa and India, she would see mothers overburdened with children competing for attention. Time and time again, she would hear these women saying, “I can’t afford to feed the ones I have now.”

Despite the mountain of data and evidence, contraceptives and family planning weren’t something Melinda could advocate for easily. They violated her church’s teaching and her own upbringing. The easy path was to quit. Stop. But instead, she asked priests, nuns and Catholic scholars, “Can you take actions in conflict with a teaching of the Church and still be part of the Church?” “That depends,” was the answer she got. “Only when you are true to your conscience, and when the conscience is also informed by the Church.”

There is a Church teaching against contraceptives, she knew. But there is also another Church teaching, which is to love one’s neighbor. “If they faced an appeal from a 37-year-old mother with six children who didn’t have the health to bear and care for another child,” Melinda thought of the Church. “They would find a way in their hearts to make an exception.” In this final discernment, love was more urgent than doctrine. Wisdom isn’t about accumulating more facts, Melinda wrote. “It’s about understanding big truth in a deeper way.” That’s how she reconciled the two values. That’s how she grew as a leader.

The Interrogation of Self

People may say only Melinda French Gates would have the time to discern the greater truth. Most people are too busy to think. CEO Jason Fried at Basecamp was too busy with his product offerings to worry over the cultural shift in the larger society.

But that’s exactly backwards. When a CEO proclaims their people are their great assets, they must take their employees as whole people. Competitive organizations always ask workers to give everything to the team. Leaders want to talk about the purpose behind their business. Well, they should know that when they do so, business will not just be about business. Leaders must be ready to engage in painful and vulnerable conversations. They must be ready to interrogate their own selves in order to arrive a deeper understanding about the world.

Not all leaders need to do that, of course. But pretending to be one way and then acting the other way can’t work.

Thanks for reading—and be well.

P.S., Starting from today till 2nd July, there’s the amazing conference called Innov8rs Connect (https://innov8rs.co/unconf/agenda/). Big names include Alexander Osterwalder, Mark Johnson, Jeff Dyer, Martin Reeves, Rita McGrath, and many others. I’ll be speaking too. I have 10 corporate tickets to give away. Those will let you attend as many sessions as you like. If you made it this far, drop me an email by hitting the reply button. I’ll send a complimentary ticket your way. See you there!

The post How Lazy Thinking Leads to Outdated Values and Causes a Corporate Meltdown appeared first on Howard Yu.

May 5, 2021

Two Charts That Show Some Conflicts in Top Leadership Are a Good Thing

I recently came across this company mission statement. I am copying it here verbatim.

“To operate the best omni-channel specialty retail business in America, helping both our customers and booksellers reach their aspirations, while being a credit to the communities we serve.”

Except for the word “booksellers,” I couldn’t have guessed it was Barnes and Noble’s. It could be anyone’s.

I then went on to read Nike’s.

“Our mission is what drives us to do everything possible to expand human potential. We do that by creating groundbreaking sport innovations, by making our products more sustainably, by building a creative and diverse global team and by making a positive impact in communities where we live and work.”

Strategy is a trade-off. It’s about deciding what to do, and what not to do. Six questions every successful company must answer:

Why do we exist?How do we behave?What do we do?How will we succeed?What is most important right now?Who must do what?Answering these questions is hard. It’s as hard as it is intellectually simple, because it requires difficult conversations and rigorous debates. And most executives prefer the comfort of their regular busyness. The questions are about strategy, no doubt. But to have real commitment demands passionate and messy dialogues among team members.

The real question to any leader is this: Will I be willing to endure the emotional pain to go through the human messiness of argument and truth-seeking?

The Steep Price of Conflict Avoidance

Most of us find conflict uncomfortable, especially in the office setting. The default for many organizations is to be passive-aggressive. We go to a meeting, smile and nod at decisions that we disagree with. We then do little to support that idea we agreed to.

Such passivity is bad between two distant departments. But it is catastrophic when it occurs in the top management team. Why? Because by default, any decisions made at the top have recurring effects across several departments. Otherwise, the discussion shouldn’t have been at the top level. A typical C-suite discussion: The head of sales can’t raise a product’s price without suffering volume loss. She needs the head of R&D to dream up a new feature. The head of manufacturing also needs to deliver without flaws.

Alignment must start from the top, because people are smart observers of their own bosses. The moment managers sense there’s a lack of unity in the leadership team, they will stop collaborating wholeheartedly. After all, if their boss won’t push them to reach out and hold them accountable for their collective effort, why bother? This is how silos begin. Organizations fracture from the top.

But if passivity is a bad thing, isn’t too much head-on confrontation also bad? Along the continuum of artificial harmony at one end and mean-spirited personal attacks at the other, should leaders aim at some “ideal” conflict point?

How most people think about the relationship between conflict and performance.

The answer is a resounding no. There are two types of conflict. You should aim high for one, and low for the other.

Conflicts That Help and Conflicts That Hurt

Bill Campbell, “the trillion-dollar coach,” worked side by side with Steve Jobs to build Apple from near bankruptcy. He also worked side by side with Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and Eric Schmidt to build Google from a startup. He coached John Donahoe, CEO of Nike. He coached John Hennessy, former president of Stanford University. Campbell was a successful CEO himself at Intuit—the maker of TurboTax and QuickBooks.

He wasn’t shy of conflict. He was “aggressive and tenacious in giving negative feedback,” said Jesse Rogers, managing director of Altamont Capital Partners. When Jesse sent Bill the link to the website of his new company, Bill called immediately. “Your website is a piece of shit!” was how Bill said hello. He ranted about how Altamont’s website was not up to snuff. This was Silicon Valley, Bill said. You couldn’t be a successful startup here and have a shitty website!

The wakeup call worked because it “came from a place of love.” When Bill yells at you, Jesse said, it’s because he loves you and cares and wants you to succeed. Nike CEO Donahoe described it as “the power of love.” It was never about Bill. “Coming from him, it didn’t hurt when he told you the truth.”

Of course, Bill’s way of loving is unique. His tough message of candor, warmth, and respect is often laced with swearing and cursing. And it might have made some feel excluded or uncomfortable. But his effectiveness also points out where executives should strive when managing conflict: You should tolerate and even encourage cognitive conflict.

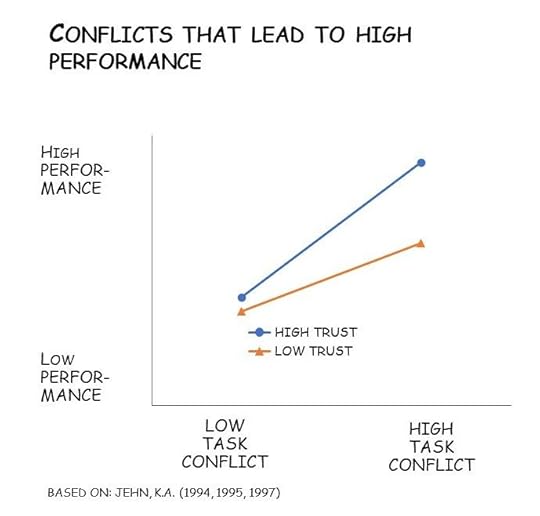

Cognitive conflict is task oriented. It focuses on judgmental differences about how best to achieve a common goal. It’s healthy when people hotly argue over an issue before a final decision is made. Cognitive conflict avoids groupthink. It taps into more diverse perspectives. And it correlates with better-quality decisions. Researchers have found that groups who experience more task conflict make better decisions because such conflict provokes a higher cognitive understanding of the issues.

But then research also shows leaders must minimize relationship conflict. This second type of conflict involves emotion rancor and personal disputes, which always lead to lower morale. They limit the information processing ability of the group; group members spend their time and energy focusing on each other rather than on the issues at hand.

Performance is highest when task conflict is high but relationship conflict is low.

In other words, a team must remember to keep a positive attitude toward one another while voicing their disagreements with others’ opinions. The key is trust. Winning teams are those that may not agree with others’ opinions, but they believe in each other’s intentions. They feel safe being candid. It all comes from a place of love.

Bringing your whole self to work

Business is never about business if you want to build trust. Successful leaders don’t separate people’s human and work selves. They simply treat every colleague as a whole person. That messy boundary of professional, personal, family, and emotions all wrapped up in one.

That’s the condition needed for team members to engage in productive, unfiltered conflict around important issues. And from such team meetings, they leave with clear-cut, specific agreement around decisions. That’s especially important when a team is dealing with non-routine tasks, which involve a great deal of problem solving and feature a high degree of uncertainty—the essence of strategy work.

This is how Indra Nooyi, the former chairwoman and CEO of PepsiCo, focused her work. She wrote letters to her senior officers’ mothers to give them a report card on how their children were doing at PepsiCo. “Thank you for the gift of your child to our company,” she would begin. These letters opened the floodgate of emotions. Parents started communicating directly with Indra. They told their neighbors, relatives, and friends. Executives got emotional because their parents had never received such a letter. “This is the best thing that’s happened to my parent and the best thing that’s happened to me,” they’d say.

Executives must be able to put the collective priorities and needs of the larger organization ahead of those of their own departments. Otherwise, a top team would work like the United Nations, where people come together only to lobby for their constituents. That’s why Indra worked hard to generate a sense of commitment and loyalty at the top. This is how strategic clarity gets made.

Thanks for reading—and be well.

This article was co-authored with Angelo Boutalikakis, a Research Associate at IMD’s Center For Future Readiness.

The post Two Charts That Show Some Conflicts in Top Leadership Are a Good Thing appeared first on Howard Yu.

April 29, 2021

Three Charts That Show Why Andy Jassy Is Great As Amazon’s CEO

Identity leads to action. A company with a strong identity, when backed by the ability to deliver, tends to win. Few identities are clearer and more specific than that of Amazon. “Start with customers, and work backwards,” intoned Jeff Bezos. “Listen to customers, but don’t just listen to customers—also invent on their behalf.”

The results bear this out. Amazon is reporting its quarterly results on Thursday, and it is expected to report a 39% increase in revenue to more than $100 billion for the first quarter. It would be the second quarter in a row that Amazon raked in record high revenues. And that would be Bezos’s crowning achievement as the CEO. His lieutenant, Andy Jassy, will take over starting this summer.

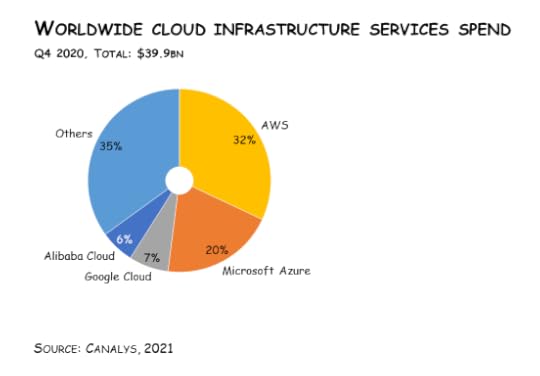

The choice was unusual but could prove wise. Jassy isn’t steeped in Amazon’s retail operations, which has always accounted for the lion’s share of the company’s sales. Jassy instead had created Amazon Web Services (AWS), a cloud computing division and a business-to-business operation, unlike Amazon.com. He then grew it into the largest cloud provider in the world. Today, AWS powers everything from Netflix and Spotify and Airbnb to the Central Intelligence Agency and the Democratic National Committee.

This is the result of the unconventional path of Jassy’s career. Jassy joined Amazon straight out of Harvard Business School in 1997 and never left. Yet he was never stuck with the mainstream business. He was on the fringe running AWS. In other words, he has been an “inside outsider.”

Amazon Needs an Identity Update

A body of knowledge from Harvard Business School has demonstrated company performance is significantly better when insiders become CEO. And inside outsiders produce the best results. They are people from the inside the company who somehow have maintained enough detachment from traditions and ideology, according to Professor Joe Bower. He writes that a successful CEO from inside needs to look at the corporate inheritance as if they are an outsider who has just bought the company.

It’s this context that makes Andy Jassy a great bet.

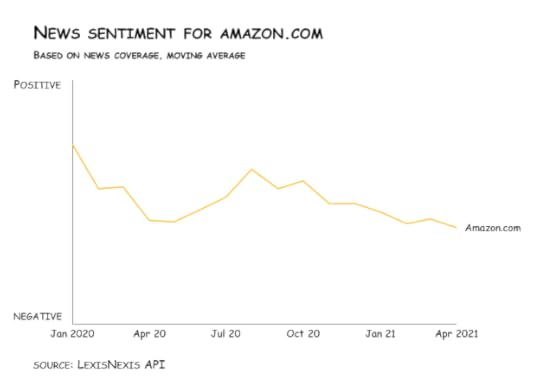

The whole tech sector faces an identity crisis. It suffers from a trust issue. And it’s hard to think of an industry that has squandered public goodwill faster than Silicon Valley. Less than a decade ago most people still believed in the startup romance. Under the romantic spell of sunny California, college dropouts would dream up new products to help change the world.

Startups do change the world. But they also turn into attention merchants, selling our gazes to advertisers. They are expanding like kudzu that engulfs one sector after the next. First newspapers, then book publishing, then brick-and-mortar stores, and now health care.

What happened is the likeability of tech giants sank. My research team has assessed public sentiment using published information. Big data style. We’ve downloaded everything written in standard bearers of business news. That included The Wall Street Journal, CNBC, and Financial Times, along with corporate press releases.

We fed ten years of data into an algorithm. We wanted to see how the general population has come to understand the tech sector. We also added the banking industry for comparison.

The picture looks grim. As much hatred as there was for Wall Street bankers and the top 1%, finance has slowly improved its image. Big tech is turning into the new epitome of greed.

Is it a wonder with the almost-weekly tech hearings in Capitol Hill? Lawmakers felt emboldened to parade tech CEOs on behalf of “the people.” More urgently for Amazon is that it needs a turnaround on its perceived image. It cannot save the sector, but it must at least try to save itself.

A Subtle but Resolute Update on Who We Are

The founder imprint of Jeff Bezos is everywhere. Amazon has done everything imaginable to lower prices for customers while at the same time increasing selection and enhancing the buying experience. It has done so with online shopping, book publishing (Kindle), music and movie streaming (Prime), and now, health care (Care).

But it’s not so great when you are trying to sell things through Amazon, as I’ve argued before.

Amazon’s Marketplace hosts millions of small-business sellers. These are third-party merchants who rely on Amazon to fulfill their orders. They still need to do most of the work: market research, making and sourcing products, and taking individual financial risks.

But Amazon competes against these merchants. It looks at sales information and then launches its own private labels to sell popular products. Amazon’s versions are, of course, cheaper.

Here is the crux of Amazon’s image problem: The world sees Amazon as a marketplace exploiting small merchants. Amazon’s singular focus on paying consumers is no longer enough. Its brutish handling of small merchants is an obstacle to fairness. It violates our sense of proper market competition.

What’s been built around Amazon’s core identity now requires an update. The Amazonians need to recalibrate their compass to guide their day-to-day actions. Otherwise, our society won’t tolerate them.

AWS has the right outlook.

From Customer Obsessed to Nursing Partners

AWS powers a huge bulk of websites, but not by hoarding data. Quite the opposite. It committed unparalleled resources to building developer tools and making access easy through standard APIs. Unless you are Facebook or Google, it’s easier to use Amazon to run your global data center operations.

It also helps that Andy Jassy is embraced because of his response to social justice issues. He’s been outspoken in the Black Lives Matter movement and LGBTQ issues. He banned social media platform Parler following the US Capitol riot.

Meanwhile, he’s known inside Amazon for holding the same intensity as Jeff Bezos. Jassy’s exhaustive attention to detail and hands-on approach, his penchant for back-to-back meetings, have all become legendary within the company for the heir apparent. People believe he “embodies the culture of Amazon,” and according to a former Amazon executive, he has adopted a lot of Bezos’s personality.

And the beauty of a lifer working on a fringe business is this: AWS values collaboration with developers more than control. This is no surprise. AWS can’t afford to have third-party developers fleeing to Microsoft Azure or Google Cloud. Without new apps and functions, AWS will lose. Unlike at Amazon.com, where the company controls everything from product curation to fulfillment logistics, AWS relies far more on others.

Jassy understands all this. He saw the importance of implementing proper governance. AWS must be clear on where to go and where not to go. In technological terms, it limits itself to making building blocks without climbing the technology stack too high. Jassy saw that other failing players are ones that “built too high in the stack.” Rather, they should have, like AWS, let third-party developers “stitch [the building blocks] together however they saw fit.” Because the higher AWS climbs, the more it will encroach on the turf of these players. An app store should never compete against an app developer. The same logic applies to AWS in cloud computing.

It’s exactly this sense of fairness rooted in AWS that will allow Jassy to view Amazon.com with enough detachment. The bargaining power with A.I. developers on AWS is not the same as with a merchant selling plastic casing on Amazon.com. While being an Amazon lifer, he comes with an alternative school of experience that he is likely to champion a new outlook from within. Picking Jassy could well be the wisest decision of Bezos’s entire career.

Thanks for reading—and be well.

P.S. CEO succession is fraught with danger. What’s your observation on successful transitions and failures? In your mind, what are the key drivers related to CEO succession? Join the discussion below.

The post Three Charts That Show Why Andy Jassy Is Great As Amazon’s CEO appeared first on Howard Yu.

April 22, 2021

How Asia’s Ride-Hailing Giant Debunks 3 Startup Myths

This article was first published in Forbes.

We tell ourselves that entrepreneurship is the fairest game in business. The smartest and hardest working entrepreneur wins. Our society tolerates and justifies disproportional financial rewards to household heroes: Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos.

It’s a narrative that even governments and universities can’t resist. When big companies get tough with layoffs and stop hiring graduates, professors tell young people to start their own businesses. Governments tell the unemployed to work on gigs. Even economic development agencies are obsessed with turning their countries into “startup nations.”

This week, Asia’s ride-hailing giant, Grab, is set to complete a $40 billion SPAC merger with US-based Altimeter. It’s a perfect window into just how delusional such understandings are. The myths of entrepreneurship collapse under the examination of Grab’s deal.

Myth 1: Everyone has a fair chance to build a startup.

For readers living outside Asia: Grab is a ride-hailing, food delivery, and digital wallet company. It operates in eight countries across Southeast Asia. CEO Anthony Tan initially launched a ride-sharing service with 40 drivers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in 2012. Grab first made international headlines in March 2018. That was when the mighty Uber bowed out by selling its operations, including those in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, to Grab.

Anthony is no stranger to the rough and tumble of business play. He’s a rich kid from a family that owns a Malaysian conglomerate and the youngest of three brothers. His father runs a local Nissan manufacturer, and the family business is one of Malaysia’s largest auto distributors as well.

Just like the kids of many well-off Asian families, Anthony was sent to Harvard Business School to get educated. To his credit, he was unlike many rich kids, who played not to lose. He enjoyed trying new things. He was curious about life outside the safety and comfort circles of crazy rich Asians. He said his family had a tough time understanding what he was trying to do, “and I don’t blame them.”

Anthony was able to explore his dream at a leisurely pace. He was surrounded by the best minds in the world at Harvard. And much like Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and Elon Musk, he grew up not having to worry about whether there would be food on the table on the next day.

Let’s not forget that material comfort and world-class education is a head start.

Myth 2: Smart entrepreneurs have original ideas.

Some have said that Anthony is a street fighter. Others have commented on his “workhorse” nature. His cofounder at Grab, Hooi Ling Tan, who was also a Malaysian in the MBA class of 2011, noticed that he lacked the typical demeanor of a tycoon’s son. “He’s actually way more hardworking than I was,” said Hooi Ling. “He’s super humble and just a nice person to be with.”

But Anthony wasn’t just hardworking and nice. He also cultivated connections. He met Steve Chen, the co-founder of YouTube, and Eric Ries, the “lean startup” guru, while at Harvard. The entrepreneurship class he took would have analyzed the business models of Google, Facebook, and Amazon. And it’s likely that he’d been taking Uber downtown when the company was taking off in the US but still not strong in Asia. It would not have taken Anthony too much imagination to see the potential of porting a similar idea over to Malaysia and Singapore.

He would have needed powerful connections, access to the venture capital world that had funded so many Silicon Valley startups. At Harvard Business School, he had met Andy Mills–the former CEO of Thomson Financial–through a Christian fellowship. Mills had since become his mentor: “As a big brother in my work, in my faith in God,” Anthony said. He wisely invited Mills to the board of Grab.

Author Guy Kawasaki said a good idea was about 10 percent implementation and hard work and 90 percent luck. You’ve got to have luck in life to be situated in the right place and make the right connection.

Myth 3: Plenty of good ideas are competing for investors’ money.

Grab is going IPO (initial public offering) through a SPAC merger. A SPAC, or a special purpose acquisition company, is essentially a shell company. Its only purpose is to raise capital through an (IPO), promising people that, at some stage, it will buy a startup.

You may think this is a twisted arrangement. It is. It allows a startup to effectively bypass all the compliance hurdles of a traditional IPO: no public scrutiny of financial disclosure, no formal filing of a detailed prospectus in the form of an S-1. In its deal, Grab will receive a maximum of about $4.5 billion in cash.

Why does Anthony need all this money? Grab is hardly making any profit. It needs to diversify to explore other businesses. From ride-hailing, it has already expanded into online food delivery. But it is experiencing similar woes to Uber and Door Dash: both businesses aren’t showing any signs of profitability, but financial services could. It’s an industry with fat margins that’s swollen with traditional banks. Anthony doesn’t need to look any further than Alibaba and Tencent to understand that Grab must grow into a super app. To facilitate that, he needs deep pockets.

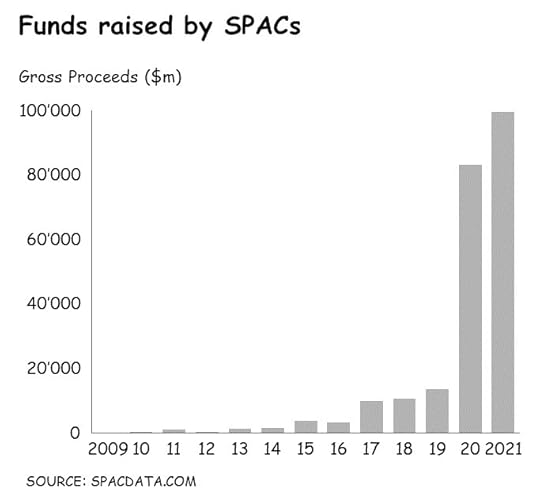

Meanwhile, SPAC has gone through the roof. Look at this graph:

There’s too much money chasing too few good ideas. It’s the world favoring entrepreneurs, not capitalists.

I don’t want to belittle the achievements of Grab or its founder. In fact, I almost worship Anthony for his audacity and willingness to sacrifice in pursuit of his big vision. He’s too different from many of the younger members of family businesses that I’ve come across.

But it’s also critical for policymakers, government, educators, and parents to know the true factors of success. Rags-to-riches are stories we remember precisely because they are rare. And increasingly in our inequitable world, it’s becoming implausible. What’s more plausible is rich-to-richer. Don’t get me wrong. It’s still hard work. But let’s not celebrate for the wrong reason.

Stay healthy,

This article was co-authored with Angelo Boutalikakis, a Research Associate at IMD’s Center For Future Readiness.

The post How Asia’s Ride-Hailing Giant Debunks 3 Startup Myths appeared first on Howard Yu.

April 15, 2021

What Is More Exciting Than Coinbase’s IPO in the Crypto World?

Gold is valuable. Pawnshops are not. When a new investment opportunity bursts onto the scene, people sometimes get confused between the value of an asset and the value of the sellers. Cryptocurrency is one such example.

Wednesday week saw the stellar IPO of Coinbase. The largest U.S. cryptocurrency exchange went public with a valuation of $85 billion. That’s a valuation almost three times that of Nasdaq, where Coinbase is listed.

Coinbase is raking in money. Its exchange serves mainly Bitcoin and Ethereum, and it charges users 0.5% on every dollar worth of crypto being traded. This is 50 times more expensive than what Nasdaq charges. Stock and bonds are charged at about 0.01% on each dollar trade. No wonder Coinbase’s revenue soared more than 800% during the first quarter this year to some $1.8 billion. Fast-growing startups usually make no money. So, Coinbase is a rare unicorn that shouldn’t even exist.

But that extreme profitability of Coinbase is exactly its problem.

Competitors like Gemini, Bitstamp, Kraken, and Binance won’t sit on the sideline for long. Traditional brokerage firms are being nudged by their customers to expand into crypto trading, too. That’s why economic theory has proven many times that “abnormal” returns can’t last long. Sooner than later, competitors will show up to steal Coinbase’s market share. A price war will ensure, and then the feast is over. How can anyone justify a $85 billion price tag?

Ironically, the inevitable decline of profitability of a crypto exchange is exactly what the market needs. It foreshadows cryptocurrencies going mainstream.

Coinbase Founder and CEO Brian Armstrong

Two weeks ago, Visa announced a new payment infrastructure that will enable crypto-native companies to settle payments directly without conversion to real money. Now, this is truly a big deal.

In the past, companies like Visa or PayPal have allowed people to buy, say, coffee using crypto. But what happens behind the scenes is a conversion from, say, Bitcoin, to fiat money on the spot to pay the merchant. Essentially, it’s only adding a conversion function on top of the existing payment system.

What Visa is doing this time is different. It is piloting a form of direct payment with Crypto.com. It works like this: customers who have a payment wallet with Crypto.com can pay for their coffee using the stablecoin USDC. Visa doesn’t convert it to anything. Instead, Visa clears the payment via the Anchorage cryptocurrency platform, the first federally chartered digital asset bank in the United States. The advantage is that without conversion, the transaction bypasses the entire traditional banking infrastructure. No more slow-moving payment through SWIFT with hefty transaction fees. The moment the customer pays, the merchant gets paid.

The beauty of bypassing SWIFT and other legacy banking systems is that the transaction fees can be driven to a minimum or close to zero. Why is that important? Because everything on e-commerce is subscription-based these days. Instead of monthly fees, why not charge by the day, by the hour, or by the minute or even second? The more precise the charge, the smaller the payment amount each time. As a result, new customers are more likely to sign up.

Here you can see the contrast of the two business models. Coinbase is making money from market inefficiency. It charges money every time people trade cryptocurrency. Visa is using cryptocurrency to drive out inefficiency from the traditional banking infrastructure. Who would you like to bet on?

Start-ups and tech companies all love the idea of zero marginal cost. The only players who would hate this are big banks, whose legacy system and infrastructure seem more and more out of date and out of touch by the day.

Such is the nature of disruptive innovation.

Stay healthy,

P.S., What’s your view on crypto? Will you invest now or will you wait and see? For those working in finance, how’s your organization prepare for this emerging class of assets?

The post What Is More Exciting Than Coinbase’s IPO in the Crypto World? appeared first on Howard Yu.

April 13, 2021

Remote Work is Here to Stay. Here’s How to Restructure Office Interactions

The interesting aspect of the post pandemic office won’t be who’s returning and who’s working remotely. It’s how we’ll change the way we interact. Certain work practices that we used to believe were perfect will become questionable.

How we innovate will be one.

Right up until the Covid lockdown, colocation, where an agile team shared an open office, was the gold standard in Silicon Valley. IDEO preached it. WeWork scaled it. And Steelcase made money by selling furniture that went along with it. The whole movement had its good points.

Being colocated gave everyone the instant knowledge of where a project was going on. They relied on less emails when asking for information. They walked right across the office to see their colleagues, when needed. In extreme cases, a company became a home and a leisure space too, especially among young professionals. Three meals a day, a gym, doctors, and massages were all provided onsite. And people loved it.

Then they woke up.

A recent survey by LiveCareer polled over 1,000 Americans. On NewsNation last week, I discussed the implications of the findings. The bottomline is, 62% of workers said they’d give strong preference to employers that offered remote work. And 29% said they’d quit their current jobs if forced to return.

That’s why remote work is something that your company, like others, must explore or come to embrace. And the first step is to be clear about what types of communication your organization currently relying upon the most and why. Then you can consider rewiring, at least for your team, so as to improve the productivity and wellbeing of your people.

Characteristics of different communication methods

Ask yourself quickly: In your current job, what percentage of your work is in each of these quadrants?

If you are like most others, your pre-pandemic work life was likely structured around high-effort communications. These were high-effort activities because you either needed to travel to a specific location or to coordinate a schedule for those meetings. Or in the case of email, you composed your request without a template. Once you hit send, you still needed to wait, sometimes for days, for the other party to answer.

Colocation was attractive in the past. It maximized the ease of face-to-face meetings and suppressed the need for other ways of communicating. More than 70% of what we say is nonverbal, expressed through body language and subtle shifts of facial expression. Face-to-face communication captures all those nonverbal cues. It is the most context-rich method. It conveys your warmth and realness. That’s why meeting in person helps overcome differences, clarify perspectives, and develop creative solutions.

And yet remote work is here to stay, for all the reasons we have discussed. What companies now need to do now is to migrate more work toward the low-effort, asynchronous format. They can’t just be forced over. The nature of tasks themselves needs to change. When this is done right, employees have less stress and more freedom. And some companies have managed it. They have done so by making documentation a priority.

Document everything and make it searchable

Good software companies document code features. Documentation either explains how the software operates or how to use it. A startup may begin by having everything in someone’s head. But for the company to scale and adapt, anything that is done repeatedly, by more than one person in the company, must be documented.

Gitlab took this idea to the extreme. It’s the world’s largest all-remote company, with more than 1,300 employees working across 65 countries, all without a physical office. GitLab obsessed over documentation. It has a centralized online handbook. Think of it as a central repository on how everything is done at the company. It’s Gitlab’s institutional memory. Anybody can update it or create a new page. After changes are made, an employee then raises a “merge request” by selecting other colleagues from the “reviewers” field. The reviewers ensure the content is technically correct and the presentation follows its documentation guidelines.

Gitlab has to overcome a natural tendency. When people wish to communicate a change, CEO Sid Sijbrandij observed, their default is to send a Slack message, send an email, give a presentation, or tell colleagues in a meeting. But Sijbrandij’s company has prioritized documentation over dissemination.

“Every piece of information is a brick,” he said. “Everyone is receiving bricks daily that they have to add to the house they’re building internally.” That’s how a company grows. But people also forget things. And things eventually become unclear. People thus waste time in a lot of meetings because a lot of context must be recreated. The beauty of documentation—whether it’s Gitlab’s online handbook or Wikipedia—is its contextual richness. Everyone can update it, keep expanding it, and make it searchable for someone when it’s needed.

Here’s how you can practice this principle right away. When you have your next meeting, use a shared Google Doc to record the decisions made. Make sure everyone can write in it, not just the most senior people in the call. After the call, people can continue to add URLs to link to external resources or internal documents, include screenshots, or to embed short videos to visualize their thoughts.

Try it. You’ll see your team requires fewer Zoom calls for follow-up clarification.

Lowering the effort of communication

To drive additional efficiency, we also need to set information free. Make it searchable over the company’s intranet by everyone. We need to shift a corporate culture from giving information based on “need to know,” to “radical transparency.” Why? Because once people are working remotely, they need to reduce the effort of coordination. Every time someone must beg for information by making a case, it’s additional friction. Decision speed slows to a crawl. People suffer burnout.

You can make radical transparency safe by having employees sign non-disclosure agreement with real legal consequences. Executives who still fear such openness really fear losing power. Knowledge is power. But hoarding knowledge is a disadvantage when you face outside competitors.

Ultimately, companies may choose to reduce communication by eliminating coordination altogether. This is possible. Amazon, Salesforce.com, Booking.com all use APIs (application programming interfaces) for internal services. I’ve explained here how APIs can drive efficiency, reusability, and faster integration.

But these are fancy things for down the road. What you can do today is to chart out what type of communication you need to shift more for your team. And start behaving that way accordingly, with your closest colleagues. You and your team members will enjoy a better workday.

Stay healthy,

P.S., What are some of your favorite remote work practices these days? We’d love to hear your tips. Join the discussion below.

The post Remote Work is Here to Stay. Here’s How to Restructure Office Interactions appeared first on Howard Yu.

April 9, 2021

Three Charts That Explain Investors Are Not Short Term, They Are Just Skeptical

Short-term pressure—that’s what everyone complains about. In my discussions with senior executives at large companies, they speak openly about the market pressure for short-term performance. Specifically, it’s the pressure from the financial market for higher earnings the next quarter. That singular focus is restricting organizations from innovating. And the number one enemy that unites all managers? The Wall Street analysts.

The one CEO who understands this all too well is Jeff Immelt. He led General Electric from 2001 to 2017. Once the world’s most valuable company at over $500 billion, GE today is worth less than $120 billion. Its businesses in lighting, home appliances, MRI scanners, locomotives, and gas power were all sold off. The company is a shell of its former self.

But Immelt wasn’t inept. He knew the importance of generating growth. When he first became CEO, his priority was reinventing GE from ground up. He rightly sold off GE Capital, a financial operation that was full of toxic assets after the subprime mortgage crisis. He expanded internationally into China and India. He developed the strategy of industrial internet ahead of his counterparts at Siemens and Honeywell. He envisioned that GE would switch from selling hardware to software-enabled solutions.

A great strategy. But the financial market never believed GE. Why’s that?

Stocks for the Long Run: General Electric vs. the S&P 500

Stocks for the Long Run: General Electric vs. the S&P 500

Immelt is charismatic. He’s articulate and well-liked. He’s willing to take chances, dream big, and think creatively. To find out what went wrong, my research team decided cross-examine data. Lots of it—big data style.

We downloaded every report published during Immelt’s tenure by the standard bearers of business news. That included The Wall Street Journal, CNBC, and Financial Times, along with corporate press releases. Then, 16 years of data were all fed into an algorithm. We wanted to look at how GE projected itself and how exactly the business community came to understand it. Such a “textual analysis” would give us a gauge on how things have evolved. We also added an industry peer for comparison: Honeywell.

Overall and over time, GE under Immelt was promotion-focused. The company played because it wanted to win. Honeywell, in contrast, was vigilant and concentrated on staying safe. Being prevention-focused also made it more risk-averse. It emphasized being thorough, accurate, and careful.

This broad description fits with the CEO behavior. Honeywell’s David Cote was hired in 2002 to lead the company. That was just a year after Immelt’s appointment at GE. Cote’s immediate concern at the time was Honeywell’s aggressive accounting practices.

“The first step to improving the planning function is to eradicate the quick fixes that keep people stubbornly focused on today at tomorrow’s expense,” then-CEO Cote recalled in his memoir. Honeywell had been offering distributors special discounts or longer payment terms during the last week of a quarter. It did so because Honeywell could then record sales before the earning announcements. Similarly, salespeople would ship products for free as a discount promotion. The company would then amortize the cost over the next 10 or 20 years. You win today, lose tomorrow. In one instance, a plant manager cut down hundreds of acres of trees around the property so that he could sell them for timber. That helped him “reach [the] goals for the quarter.”

None of these are legally wrong. But Cote was determined to eliminate all shenanigans. No more bookkeeping gains, one-time “specials,” or distributor loading. He didn’t care what it cost in income. He scrubbed clean the financials because he likes to be thorough, accurate, and careful. He said repeatedly, “Delegate as a leader, but don’t abdicate.”

Next, he pushed the idea of “perpetual restructuring.” He would spend $10 to $40 million each quarter on restructuring. He wouldn’t max out any one-time gains in profit because of the sales of a business. And when Honeywell had a great quarter, he rechanneled earnings for process improvements. Rather than riding high on something one-off, he systemically paid down technical debts over time. Under-promise, over-deliver—that’s what you do when being prevention-minded.

It’s an interesting contrast to GE. In February 2008, at a probe by the Securities and Exchange Commission, GE had to restate two of its previous financial results. It disclosed additional accounting errors since 2005. The only thing that remained unchanged was the outlook at GE—it remained optimistic while Wall Street became increasingly skeptical.

Share price performance during Immelt’s tenure compared to Honeywell’s

How Did Wall Street Make Up Its Mind?Now you ask, how exactly did Wall Street come to a consensus? How did the market choose to believe in Cote but not Immelt?

There are usually a good number of experienced analysts who track a company. They write research reports for mutual funds, hedge funds, and large banks—institutional investors who make the buy/sell decisions for our pensions.

The Wall Street analysts are being evaluated all the time. They are judged by their records of making accurate forecasts. They are also ranked openly by this ability—publications like Institutional Investor regularly publish the analyst rankings. Winners routinely brag about making it.

Think for a minute here—is there any job performance that’s more transparent than this? Could you imagine your annual performance being benchmarked against those who hold a similar job at other organizations, with the rankings easily search via the internet?

An example of analyst rankings taken from tipranks.com/analysts/top

An example of analyst rankings taken from tipranks.com/analysts/top

I am not saying this is a good system. But the relentless open evaluation of the job performance of an analyst makes them view the world with a dose of skepticism.

Imagine you are an analyst. When faced with questionable stories, you’ll naturally go conservative. You don’t just listen to the CFO or CEO. You can’t blindly trust corporate communication. Just because a company has an exciting plan doesn’t justify buying the stock. Management routinely fails to execute a company’s plans. Turnaround stories usually disappoint. Hot products or services can come to an end quickly. Superior technology or a patent doesn’t guarantee success. Mergers rarely work.

With so many failures, why would Wall Street suddenly become enthusiastic about another me-too, also-run digital transformation? As a veteran analyst summarized, “If you’re using a valuation methodology that differs from most market [analysts], you need to be prepared to quickly tie your methodology back to theirs.”

How Do Analysts Change Their Viewpoint of a CompanyNow we see why analysts seem “short-term”–focused. They don’t change their viewpoint on companies arbitrarily. The market isn’t likely to revise the share price until the company’s revenue starts to beat consensus a few times. Analysts don’t trust the CEO’s rhetoric until they start to see some concrete results.

That’s why it’s so important for an incumbent to deliver today as well as building growth prospects for tomorrow. Note that when I say “delivering today,” I include both financial performance as well as tangible, demonstrable traction on whatever transformation you have in mind. Break down the grand vision into early indicators. Show the world that you are not just working toward it but generating momentum already.

The status of a growth stock is earned over time. It’s not something a CEO or a board can announce. Executives sometimes do not like the fact that the market tells them when they are not doing a good job, just like most students do not like to get bad report cards.

Thanks for reading—and be well.

P.S. Management is a hard job. What are some of the cautionary tales of failed transformation you’ve seen? Is innovation and transformation at odds with the financial market? What’s your view? Tell us your thoughts. We’d love to hear from you.

This article is co-authored with Angelo Boutalikakis, a research associate at the Center For Future Readiness at the IMD Business School

The post Three Charts That Explain Investors Are Not Short Term, They Are Just Skeptical appeared first on Howard Yu.

April 6, 2021

4 Charts That Explain Why Companies Must Embrace Remote Work: Employee Voice

The pandemic is far from over. But employers can’t wait to see their workers back. Most desperate of all are real estate developers. Whether it’s in New York, San Francisco, London, or Hong Kong, office vacancy has hit a record high. Average rental prices haven’t quite fallen by the same degree. But that’s just a matter of time. In previous slumps, falling rents lagged vacancies by about a year.

Source link: bloomberg.com

So the hopeful say workers will return to their offices in the near post-corona era. City politicians appear to be the most eager. Their tax revenues count on the cafés, pubs, and restaurants that rely on the teeming crowds of office workers.

Some bosses also see working from home as a “pure negative.” Others argue that in-person presence, bumping into colleagues in hallways and around watercoolers, are key to foster innovation and to maintain a company’s culture.

Maybe.

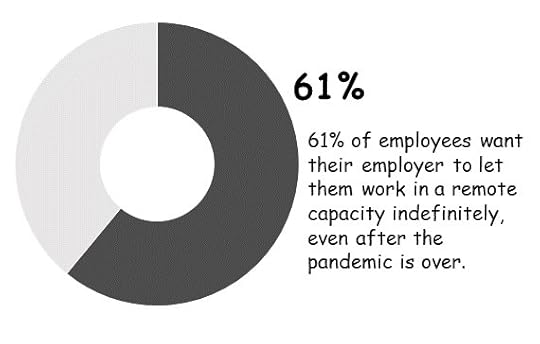

But this debate has been partly settled by the workers already. They see things differently. 61% of workers said they would prefer that their companies make remote work permanent—indefinitely—according to a survey by LiveCareer that polled over 1,000 Americans.

Not only do the majority want to stay away from the office’s watercoolers forever, but also, if people are forced to return, they would quit. 29% said they’ll go work for someone else if that happens.

The bottom line? People prefer employers that offer flexibility. Very few people actually want to see their colleagues from nine to five every day.

Now some bosses may say, “I’ll just pay above the market rate.” Sure, but if you need to pay more money to retain key talents and then pay for the office space and free coffees and running the staff cafeteria, that’s clearly not economically competitive.

That’s why you see that even among tech companies, they have office staff returning on a time schedule, driven almost entirely by the company’s own attractiveness. More specifically, how posh its headquarters are. The pampering of the physical space is essentially a form of wage top-up in asking people to return.

The Information, an influential Silicon Valley publication, has compiled an extensive list on how tech companies plan for their employees’ return:

1. Most days in office, similar to pre-pandemic levels, while adjusting for the new, virtual work routines:

Apple, Netflix, Google

2. Hybrid mix of in-office and remote work, with employees having the flexibility to choose their own arrangement:

Microsoft, Uber, Salesforce, Facebook, Adobe, Cisco, Snap, Twitter, Zoom

3. Remote first, where most staff won’t work in an office but can meet up at the headquarters:

Shopify, Dropbox

4. Fully remote, with minimal or no office space:

Gitlab, Zapier, Cameo

In the tech sector, employees are notoriously difficult to retain. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings admits his company pays top talents more than any other company would offer them—even if it’s more than what employees are asking for.

Notice that it’s only Netflix, Apple, and Google in Silicon Valley that can afford to put up a straight face, expecting their employees to return in droves to the headquarters. Others, well, they adjust and adapt. Because they must.

Work related or not, who doesn’t want to hang out at Apple’s $5 billion HQ?

I have a hard time thinking this dynamic is confined only within Silicon Valley. After all, so many companies outside of the IT sector are also pursuing “digital transformation.” They are competing for the same talent pool of data scientists and software developers.

Meanwhile, smart companies or smaller upstarts will use remote work as an attraction to poach experienced managers from the bigger incumbents. The result is a race to the bottom. Everyone is forced to embrace remote work, gradually in the beginning and then suddenly all at once.

What this means is that companies must prepare themselves ahead of time. There is so much that organizations must learn to minimize the need for face-to-face meetings. Simplifying workflow and eliminating complexity are the most obvious areas for improvement.

As I argued here before, the time is ripe to learn from those “remote complete” organizations. Their leaders have built a system to keep employees motivated and consistently productive while monitoring progress from a distance. They are living future work today.

Like many other business trends, remote work is obvious. You don’t need a crystal ball to see that it’s coming. Being smart is not about foretelling the future. It’s having the ability to develop and implement new strategies as the future unfolds. Successful companies are the ones that close the gap between knowing and doing. They figure things out along the way. Laggards are the ones that keep talking with no action.

Thanks for reading—and be well,

P.S. What’s the discussion on remote work at your company? Has it announced its plan? Are you going back to the office in the long run? What would you prefer if you have a choice? Tell us your thoughts. We’d love to hear from you.

This article is co-authored with Angelo Boutalikakis, a research associate at the LEAP Readiness Project.

The post 4 Charts That Explain Why Companies Must Embrace Remote Work: Employee Voice appeared first on Howard Yu.

March 31, 2021

How Leaders Should Make Critical Decisions

Bias for action: That’s what we are told. But we are also told to think before we act. That’s why it is key to spot decisions that have minimal consequences. They are the ones that require less debate. You should spend time only on decisions that lead to big outcomes.

Jeff Bezos of Amazon likes to classify decisions as type 1 or type 2. Type 1 choices are irreversible. They are one-way doors. If you walked through and didn’t like what you saw on the other side, Bezos wrote, you couldn’t get back to where you’d been before. He said that when making such choices, you had to be methodical, careful, and slow, with great deliberation and consultation. You could not move fast and break things. Not even at Amazon.

But Bezos also noticed that most decisions weren’t like that. Many were reversible, like two-way doors. You could back out if you wanted to. You didn’t have to live with the consequences for that long. When making type 2 choices, decide quickly or delegate to a small group of smart individuals. You’ve heard this before: Embrace empowerment, autonomy, and experimentation. Fail fast to succeed early.

The key, therefore, is to be clear on the decision types. Your team must avoid one-size-fits-all thinking. There’s no room for intellectual laziness. When making irreversible decisions, dissent is your friend, not your foe. You don’t want unthoughtful risk aversion. But you can’t afford groupthink either.

M&A: The One Thing You Need to Get Right

Mergers and acquisitions are one-way doors. And companies fare poorly: 70% to 90% of M&As end in failure, and that’s the general conclusion of most studies.

This has many causes. A company doesn’t normally acquire other firms very often. The general lack of experience means that managers only see potential deals brought up by bankers and private equity, whose single motivation is to make deals. But more troubling is how decisions on M&A get made.

Imagine that you work at a manufacturer making control systems for aircraft cockpits. A business leader spots another company that makes control systems for cabins. So they think that an acquisition makes sense. For the first time, the company can offer customers—the airlines—a combined solution: one single control system for the entire aircraft. A brilliant strategy.

In a decentralized organization, the business leader would directly negotiate with the seller. They then would submit a financial proposal for corporate headquarters to approve. But here’s the thing: How do you judge if the deal was overpriced or not?

Typically, there’s a finance team from headquarters that conducts due diligence, investigating whether the company you want to buy is really up to what’s claimed on paper. It wants to make sure there are no hidden legal liabilities and no shady business involved. But the fundamental nature of the negotiation remains unchanged. It’s the person who found the deal to follow up and negotiate with the seller.

This is bad. Because it’s hard for the same person to walk away from the deal. After months of hard work, they have already fallen in love with the company they want to buy. This is classic escalation of commitment. People stick to their guns. It’s the price we’ll pay to execute our strategy, they’ll say.

This makes no sense, of course. If you overpay in an acquisition, your strategy will never see the expected financial benefit. The amortized cost will eat up all the future profit you seek to create in the first place.

The only way to avoid such irrational behaviors is to make the dissenting voices heard. Separate deal-making from deal-negotiating. Split the responsibility.

Honeywell booth at the 3rd China International Import Expo (CIIE) in Shanghai

Promoting the De-Escalation of Commitment

That example of an aircraft control system was real. It was Honeywell’s acquisition of Baker Electronics in 2002. Honeywell overpaid and ended up with a $20 million write-off a few years later. Shortly afterward, then CEO David Cote installed a new system. It was the overhaul that finally turned Honeywell into a world-class M&A machine.

Business leaders would still identify candidates for acquisitions. Cote actually pressed them even harder to aggressively scour the market. He wanted to build a broad pipeline of acquisition targets. “You have to kiss a lot of frogs before you find your prince,” he wrote in his memoir.

Things get interesting once the target was identified. After the potential deal was put together, the business leaders would step back. The corporate M&A team takes over the actual negotiation. The business leaders didn’t like it at first. They felt like they were losing control. But Cote noted it was a lot easier for someone to walk away from a deal when they were not the one who’d put it together hoping that it’d work out.

This idea of promoting alternative viewpoints is obviously not only applicable to M&As. It’s crucial whenever decisions aren’t reversible.

Farming for Dissent at Netflix

At Netflix, employees use a shared spreadsheet when proposing an idea. You invite dozens of colleagues for input. They then rate your idea on a scale of -10 to +10 with explanations and comments. CEO Reed Hasting uses this method to get clarity. The spreadsheet system is simple, and it gathers assent and dissent, he noted. That’s how Hasting collects feedback before making important decisions.

He learned his lesson the hard way. It was the biggest debacle in Netflix’s history. Back in 2007, when DVD rental by mail was still a gigantic business, Netflix would charge $10 a month for DVD mailing and online streaming. Hasting foresaw the importance of the streaming service. He understood Netflix should become ready for the imminent shift in consumer behaviors. He also wanted the streaming operation to focus on innovation, and the DVD rental to focus on efficiency. So he decided to split up the company.

Reed Hasting, CEO and founder of Netflix

Hasting created Qwikster, which charged $8 a month for DVD rental. Netflix would provide online streaming only for $8. Customers who needed both thus paid $16 in total. It’s a price hike.

Customers hated it. Millions of subscribers left. Netflix stock dropped by 75 percent. Months would pass before the company recovered. In the post-mortem, the managers confessed the CEO had been so intense in his belief that they’d felt powerless. They’d been afraid to speak up. “I should have laid down on the tracks screaming that I thought it would fail,” said one VP. “But I didn’t.”

These observations aren’t meant to make us suffer analysis paralysis. But we need to be clear about what types of decisions we are making. Ask yourself:

Among the decisions that you are making this coming week, which are two-way doors? For those type 2 decisions, explain to others that you can back out if they don’t work out. Relax the control. Give power to those who actually do the work. For type 1 decisions that are irreversible, did you check with people with alternative viewpoints? Did you actively farm for dissent?If you don’t want to farm for dissent online, you can do it the old fashion way. Put out the situation you face before your team members, as well as your recommended actions. Let them come to their own conclusions. You divide the team into breakout groups for deliberations to avoid groupthink. Sometimes your team might agree with what you’ve proposed. Other times they generate solution you may not have thought of—and that’s great.

Remember, you are not building consensus here. You still own the consequences of your choices. You are checking your biases. Am I increasing commitment because I have fallen in love with my own ideas?

Stay healthy,

P.S., What’s your company’s approach to ensuring high decision quality? If you have tips and methods that help with your own decision-making, please share them with us. We’d love to hear your experiences.

The post How Leaders Should Make Critical Decisions appeared first on Howard Yu.