Fluid Identity: Your Corporate Strategy Depends on It. Here’s How You Can Achieve It

Smart leaders read. They read a lot. Bill Gates reads about 50 books per year, which breaks down to about one per week. Former PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi read 10 textbooks from cover to cover over one holiday. Tesla’s Elon Musk taught himself rocket science because, as he put it, “I read books.” Towering above all is Warren Buffet, who reportedly reads between 500 and 1,000 pages per day.

It wouldn’t matter so much if our world moved slower. But the pace of change is only quickening by the day, be it in artificial intelligence, materials research, engineering, biology, climate, or global politics—in short, everywhere. Those who carry with them fewer mental tools to explain things are suffering. They can’t think laterally. They can’t come up with original solutions. They don’t have the courage to take a different tack. In short, they can’t cope.

It’s interesting to see just how leaders lose grip on reality. After all, they are the ones with plenty of help: market intelligence, external board members, managers who ferret out data of any sort. Yet, a leader can get locked into a strong identity and not be able to get out.

The Danger of a Strong Identity

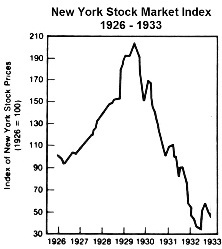

In 1929, a crisis hit Wall Street. On Black Thursday, October 24, a record 12,894,650 shares were sold. The stock market plunged the following Tuesday on October 29, with another 16,410,030 shares dumped. Stock tickers at the New York Stock Exchange ran hours behind because the trading volume was too large.

Soon enough, companies were having trouble getting loans from banks, so they were forced to lay off workers. People who became unemployed bought fewer products. A vicious cycle ensued.

Presiding over the Great Depression was Herbert Hoover. An ardent conservative, the 31st president of the United States saw self-determination as the key to recovery. He believed in self-government. He preferred decentralizing responsibilities to the local base. He thought individualism was the essence of America, that nothing should ever undermine an enterprising individual whose self-initiatives would grow into greatness someday, and that nothing was worse than a drift toward European paternalism and state socialism.

In the next two years, unemployment would soar from 3 percent to an all-time high of 25 percent, totaling some 15 million people. The stock market would be reduced to about 20 percent of its initial worth. By 1933, more than 5,000 banks, nearly half of America’s total, had failed. Instead of changing tack, Hoover persisted in his initial belief.

Why Party Loyalists Won’t Consider Policies

Psychologists have long observed that people vote primarily based on identity, not on actual policies. When a potential legislation calls for higher taxes to fund elementary schools, for instance, a typical voter won’t consider, “I don’t have any children, so I won’t benefit from the legislation.” Instead, the person is likely to think either (a) “I am a person who supports schools; therefore, I will vote for this,” or (b) “I am a person who doesn’t believe in the public school system; therefore, I will not vote for this.” Who you are and what you believe matter more than the actual policies.

Research shows that the more central a role political identity plays in the way people see themselves, the more likely they are to vote along the party line. They vote even when they dislike their party’s candidate. “I am a Democrat, and this is how we Democrats vote”—so goes the thinking.

Conversely, London Business School’s Stephanie Chen and Chicago Booth’s Oleg Urminsky found that party affiliation has less influence on the way people vote among those who see politics as a peripheral aspect of, rather than central to, their personal identity.

These are independent voters who limit party affiliation to a small part of their being. Instead of letting political identity take over their entire self-regard, they allow themselves to be swing voters. They swing because their identities are more fluid. They would adjust based on the changing circumstances.

For leaders, this ability to adjust can prove vital.

I Am Right, You Are Wrong

Hoover understood the cause of the Great Depression with amazing clarity: As early as 1923, before he became president, Hoover publicly warned that, sooner or later, the booming economy of the 1920s was going to go bust. He was concerned about New York banks’ dangerous practice of lending money to investors so that they could buy stocks “on margin.” And yet, he handled the Depression with the conviction of a religion.

Having grown up with a belief in “rugged individualism,” Hoover seemed to affirm that in America, each individual was responsible for their own well-being. He despised direct aid. The thought of giving handouts to people too lazy to work and then tax others who worked hard was immoral. “We cannot squander ourselves into prosperity,” he repeatedly said.

Meanwhile, despair was stalking city streets as well as the countryside. Shantytowns of the homeless—now called Hoovervilles—spread across the nation. Americans everywhere were asking their government for help. But when the shouts got louder, Hoover heard less and then stopped listening altogether. He sent letters saying he was too busy to receive any delegation. Reinforced police patrols surrounded the White House; barricades were erected to close the nearby streets to traffic. In July 1932, the President had the army, with fixed bayonets and tear gas, drive protesting veterans out of Washington.

Crisis Doesn’t Reveal Character, Identity Does

It’s true that no one in the government at the time knew what was needed to end the Great Depression. The idea that a central bank could have bought government bonds to inject money into the economy didn’t exist. The intellectual architecture for that kind of intervention—quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve—wasn’t around yet.

Still, the grip of the identity of traditional conservatism, aided by the President’s allies, had formed a toxic bubble that barred all other considerations. To some of his fellow lawmakers, the Depression was exacerbated not because Hoover wasn’t doing enough, but because he was doing too much!

Keep Your Identity Fluid in Business

That catastrophic outcome was hardly predetermined. To visualize a new identity, however, would require not only mental flexibility, but the mixing of metaphors and symbols. An entrepreneur might say “I’m building the Uber for X,” or “It’s like Netflix for Y.” An identity is a reflection of the concrete and real, which explains who we are and why we behave in a certain way. It also dictates what problems a company will solve for its customers.

A textbook case in business is how Fujifilm (still a chemical giant) and Polaroid (now bankrupted) chose their identities differently.

On the surface, Fujifilm and Polaroid were similar: They were both dependent on film sales. However, they had different reactions to digital imaging, based to a large extent on identity. Fujifilm adopted a broad, robust identity as an “Information and Imaging” company and explicitly included digital imaging in its set of activities. Polaroid, meanwhile, maintained a narrower identity as an instant photography company. Digital imaging challenged Polaroid’s identity, and the company’s resistance to it ultimately led to its demise.

Identity thus provides an overall logic as well as a clearer and deeper expression of a firm beyond its everyday activities. It’s a leader’s job to avoid being locked into one single identity when it becomes unfit.

To do this well, one must possess a wide repertory of possible selves. Benchmarking one’s company against industry peer groups only leads to a dead end. Copying others’ best practices will, at best, help you become a fast follower. Most effective is to borrow industry logic from other spheres, and then mix and match according to your own need. You need to reinvent on your own ground.

Change Your Own Identity

At a personal level, it’s important to have a wide range of possible selves too. During career transition, for example, successful managers are the ones who actively tap into diverse role models. Research shows that they intuitively understand the big difference between imitating someone wholesale and borrowing selectively from various people to create your own collage, which you then modify and improve.

Most of us have personal narratives about some defining moments that taught us important lessons. But the most effective leaders never allow the stories of their past and the images they have painted of themselves to take them hostage in a new situation.

That’s why reading autobiographies has great benefits. Not only do you get to learn about what an individual has been through and, more often than not, gain knowledge regarding how to act in specific circumstances and deal with difficult stages of life, but the great personalities we read about are virtual mentors who widen our range of thought. Their stories provide ingredients for us to experiment with. Like chameleons, we borrow styles and tactics from successful people, even if we don’t agree with them completely.

Bill Gates does not start a book unless he knows he is going to finish it. “It’s my rule to get to the end,” even when he disagrees with the author. If he disagrees with a point the author makes in the book, he writes his own viewpoint in the margin. Then he goes on to read about 50 more books a year.

Warren Buffet would go further:

“Read 500 pages like this every day. That’s how knowledge works. It builds up, like compound interest. All of you can do it, but I guarantee not many of you will do it.”

Stay healthy,

P.S. What are your thoughts? Any tips regarding reading habits? What has helped you or your company reinvent in the past? Please let me know in the comments below. Join the discussion.

The post Fluid Identity: Your Corporate Strategy Depends on It. Here’s How You Can Achieve It appeared first on Howard Yu.