Daniel Miessler's Blog, page 85

April 21, 2019

The Difference Between Goals, Strategies, Metrics, OKRs, KPIs, and KRIs

Anyone who’s been in business for a while has had the conversation about measuring performance. The topic makes some people radiate with joy and gives others a case of severe narcolepsy.

Here I want to talk about a few different business terms that are too-often conflated or confused, which are: Goals, Strategies, Metrics, Objective Key Results (OKRs), Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), and Key Risk Indicators (KRIs).

Standard in this context means that the system needs to be agreed upon by presenter and audience.

Goals are desired outcomes, e.g., increase sales, improve our hiring process, or increase profit by 35%.

Strategies are prescriptive plans or methods of achieving stated goals.

Metrics are standards of measurement that capture the efficacy, performance, or quality of a plan, process, or product. The term Metrics is quite general, and applies to any situation where the purpose is to keep track of progress against a goal. Examples include, Number of Sales, Revenue Generated, Accidents this Quarter, etc.

OKRs often have a single goal but multiple key results.

Objective Key Results (OKRs) combine both goals and metrics into a single system focused on simplicity and business alignment. The system works by filling in the statement,

“I will _____ as measured by ______.”

An example of an OKR would be a goal of “Improving Customer Service”, as measured by “Improving Positive Survey Results by at least 25%”.

KPIs feel like the weakest term here, because they’re really just a high priority metric for the business.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are metrics for key business objectives, so you don’t want to call every business metric you have a KPI. Examples might include, Average Sale Per Customer (for a sales organization), Time to Resolution (for a customer service group), or Time to Remediation (for a security program).

Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) are designed to alert decision-makers that the risk level for some component of the business is nearing—or has crossed—a predetermined threshold of tolerance. Examples might include: the probability that a key hardware component will fail, the number of complaints per 1,000 customers, Reported Workplace Incidents, etc.

The main difference between Metrics and other terms is that some of the terms include objectives, which Metrics do not.

Key differences between measurements

Because so many of these sound similar, it’s important to call out the distinctions.

The difference between a Goal and a Strategy is that a strategy is a defined way of achieving Goals. Goals are the objective, and strategies are how to get there.

The difference between KPIs and KRIs is that KPIs are generally for positive elements, such as Sales per Employee—which you want to be high—while KRIs you want to keep lower than a certain threshold.

The “Key” part of KPI should remind you to limit their number.

The difference between KPIs and regular metrics is that KPIs are the things that—if you don’t do them well—the business is almost guaranteed to fail. You don’t want to make every metric a KPI, because if everything is critical then nothing is.

If a decision cannot be made as the result of consuming a given metric, ask yourself why you’re tracking it.

The difference between OKRs and KPIs is that OKRs are focused on both the objective and the success criteria, whereas KPIs are often tracked without defining what a good or bad number actually is (and those numbers can change).

Summary

Metrics are like Intelligence in that both are designed to improve our understanding of reality.

Regardless of the system, always remember that the purpose of measurement is to improve decision-making through a better understanding of reality.

Metrics are measurements of things that matter to help you make better decisions.

KPIs are your bussiness-essential metrics.

KRIs are operational-risk monitors to make sure you’re operating within risk tolerance.

OKRs are a combination of objectives and associated measurements.

Notes

My favorite article on OKRs Link

—

Subscribe for one coffee a month ($5) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month.

April 19, 2019

My Predictions for Who Will Die in Game of Thrones

I normally write about security, technology, and how they interact with humans, but I’m making an exception here for a prediction on Game of Thrones.

I read a book recently called Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, and it talked about professional predictors of complex events. They get rated on how accurate they are, how much confidence they put into their predictions, and how much they miss by.

This text will not be modified after April 19th, 2019 other than what’s indicated in the notes below.

So I simply want to know how much I’ll miss by for specific predictions on how the story will unfold.

Characters

Basically, imagine the most heroic ends possible—with most people dying and a few random and tragic deaths—and that’s what we’re going to get.

Arya will probably live because she becomes part of the mystery and danger of the world, and Tyrion probably lives because he becomes the tragic hero that carries forth wisdom and kindness going forward.

Notes

Hat tip to Andrew Ringlein, who I’ve talked to dozens of times about this exact topic over the last 8 years or so. He’s read many other books by George R.R. Martin and believes that he has a predictable pattern of heroic story arcs. So I’m sure he’s influenced my thinking on this, but I think we disagree on a number of these outcomes.

—

Subscribe for one coffee a month ($5) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month.

April 18, 2019

Machine Learning Will Capture the ‘Je Ne Sais Quoi’ of Human Existence

Human genius has always been something of a mystery.

Experts often cannot articulate how they know someething to be true.

When a world-class chef smells something—crinkles his nose and says it’s not right—there’s a good chance he doesn’t know what’s wrong with it. Malcolm Gladwell told us the story of an art expert who knew instantly that a certain piece was fake—but she was unable to give any reasons for this assessment. And it takes both training and experience for a terrorism expert to look at a city street and know if danger is imminent.

It’s often said that true geniuses tend to be bad at teaching their craft.

This gap between knowing and explaining gives the elite among us a magical aura. It’s as if the best among us are tapping into a river of divine knowledge, and they’re given the ability to execute—but not to understand.

When something has a hidden element that makes it special, we often use the French phrase, “Je Ne Sais Quoi”—which means, “that certain something…”

But science is now telling a different story—a more antiseptic tale of opacity and complexity. It tells us that we have one mind that does things automatically, and another that thinks slowly and rationally. It says the automatic part has access to more information, which it uses to make decisions before (and even without) our awareness.

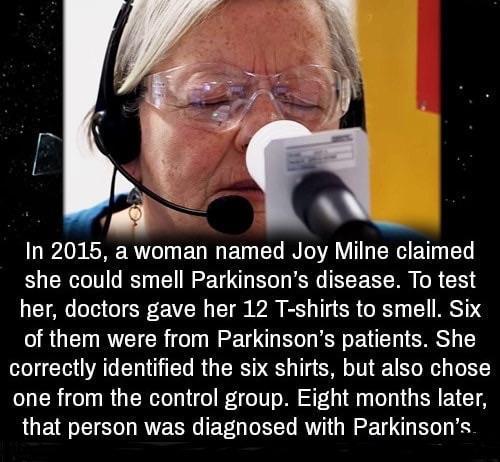

They actually told her she got one wrong, but that patient turned out later to have the disease as well.

Another example of this is a woman named Joy Milne, who could smell Parkinson’s Disease. She smelled the shirts of 12 people and identified who had the disease before doctors could do so any other way.

But could she tell the doctors what she was smelling? No.

Just like a fighter can’t tell you exactly when they’re going to attack—or a veteran pilot can’t tell you why they’re making a thousand micro-adjustments while making a difficult landing—the answers simply appeared to them unconsciously, and they either reacted or answered without understanding the source.

So rather than wielding it, the best in the world experience their greatness, much like people watching from the outside. Their brains parse more sensory inputs than they can possibly have awareness of—faster than they can keep track of—and then produce answers that they often can’t explain.

The best in the world experience their genius more than they wield it.

Algorithms are also using graytone-sensitve cameras to detect cancer better than human experts.

The combination of multiple sensor types with machine learning will allow us to find patterns far more numerous and subtle than humans can find on their own. Just as dogs can smell drugs better than us, and Joy Milne can detect Parkinson’s better than most humans, the combination of spectral analyzers and ML will likely be able to “smell” many other diseases by simply observing your dirty clothes.

Sure, but why does this matter?

There are many who still see machine learning as statistics with an attitude, or as something that’s novel and noteworthy but not useful in everyday life.

First, we need to understand that the modern era for ML has just begun. Machine Learning goes back to the 1960’s, but never saw much practical success or attention until DeepBlue beat Kasparov in 1997. And even then we still thought it was nearl impossible to automatically identify objects within images.

It’s only within the last 10 years that we’ve made object recognition so approachable, beaten humans at Go, Poker, complex strategic video games, and developed the ability to generate realistic-looking human faces in real-time.

10 years, out of the 200,000 of our species, and the 150 of our scientific awakening. That’s a blip of extraordinary advancement.

Second—and much more important—is the fact that there are many things AI will be able to analyze that have always been elusive to humans. Things that matter.

Is this person lying to me?

Is this a good business deal?

Should I date this person?

Which city should I move to based on my values and skills?

What career should I recommend for my daughter?

What policy change would produce an economy that helps the most people?

Some of these questions can be answered by human experts, but the more complex the question the more questionable their accuracy.

It’d be like Joy Milne smelling 100,000 shirts at once, looking for 1,000 different diseases. When things become sufficiently complex, human sensory input and processing power become overwhelmed—resulting either no answer, or—and often much worse—the wrong answer.

The power of prediction within chaos

The most useful part of ML will likely be allowing us to glimpse the future in the form of real-time analysis and predictions. There are millions of situations where we as humans only get to guess about things that really matter, and ML will help us see deeper into those situations to make better decisions.

The “why” piece is harder right now, but there are promising paths for making the variables more transparent.

The chances of a start-up failing (and why)

How long is this relationship likely to last given our respective profiles?

The odds that someone is lying based on their tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language

The chances that a given street is dangerous, and adjust the recommended route accordingly

The chances that a contractor is likely to collect and steal internal documents from an organization

Predicting health outcomes given your current behavior

Chances of a given product in the field to fail within a certain time period

In short, the promise of Machine Learning is being able to capture not only what human and animal experts can currently do, but also to take that to an Nth level using the power of sensor technology and computing. The sensors provide an ocean of new inputs, with far more chances to find patterns, and the computing resources allow us to process all those new variables at blinding speed.

ML will allow us to see patterns and truths in daily life that would have otherwise been invisible.

It’s not about finding random patterns that nobody cares about. It’s about finding that certain “I don’t know what” in a business, product, interaction—that gives you the insight you need to make the best decision.

—

Subscribe for one coffee a month ($5) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month.

The Toxicity of Fear

Fear is toxic to creative thought.

It will rob you of courage, of your creativity, and of your passion. It will turn you into an empty and uninspiring version of yourself.

If you start thinking about something ambitious—and feel fear take hold—figure out where it’s coming from.

Peoples’ biggest regrets at death’s door are not the things they did, but the things they didn’t do.

If it comes from within, look into ways to deprogram that. If it comes from your manager or your company, start looking at options.

But never accept it.

To accept fear is to accept mediocrity.

Reject both, and be the version of yourself that you’d like to read about.

—

Subscribe for one coffee a month ($5) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month.

April 15, 2019

Cybersecurity

Cyber Security—also called Information Security, or InfoSec—is arguably the most interesting profession on the planet. It requires some combination of the attacker mentality, a defensive mindset, and the ability to constantly adapt to change. This is why it commands some of the highest salaries in the world.

“Cyber” vs. Information Security

People who’ve been in Information Security for a long time tend to really dislike the word “cyber” being used in a non-ironic way to describe what we do. But we’re getting over it.

One of the most common questions in the computer security industry is the difference between Cybersecurity and Information Security. The short answer is, “not much”. But the long answer is, well…longer.

Essentially, “Cyber” is a word from pop culture that actually fit our digital future fairly well, with the merging of humans and technology and society. In the beginning, “CyberSecurity” was used as a way to glamorize or sensationalize computer security, but over time people started using it in more and more serious conversations. And now we’re stuck with it.

If I had to give any distinction today (2019) it would be that Cybersecurity is a bit larger in scale than Information Security.

Information Security has always had a tie to protecting data as a core part of its identity. CyberSecurity, on the other hand, includes more connotations around protecting anything and everything we depend on—including things like critical infrastructure.

CyberSecurity is such a big field, however, that it’s useful to break it up into sections. I’ve done this over the 20 years that I’ve been writing about security, and here are some of the areas in security that you might find interesting.

Sales and marketing teams often conflate these definitions, leading to confusion in the industry.

Offensive Testing: When to Use Different Types of Security Assessments, The Difference Between Pentesting and Red Teaming, The Difference Between Threats, Threat Actors, Vulnerabilities, and Risks, The Difference Between Events, Alerts, and Incidents, Security Assessment Types

Security Tools: Shodan, Masscan, Nmap, Tcpdump, Lsof, iptables

My cybersecurity career guide takes you step by step through the process of building a security career.

Building a Security Career: Building a Career in Cybersecurity, Information Security Interview Questions, Cybersecurity Lacks Entry-level Positions

Security Philosophy: Secrecy is a Valid Security Layer

Security Concepts: Encryption vs. Encoding vs. Hashing, Information Security Definitions

Attack

Security Assessment Types

The Difference Between a Vulnerability Assessment and a Penetration Test

The Difference Between Red, Blue, and Purple Teams

A Masscan Tutorial

A Bettercap Tutorial

How to Use Shodan

When to Use Vulnerability Assessments, Pentesting, Red Team Assessments, and Bug Bounties

Purple Team Pentests Mean You’re Failing at Red and Blue

An nmap Primer

Defense

Obscurity is a Valid Security Layer

An iptables Primer

The Difference Between Events, Alerts, and Incidents

Information Security Metrics

Same Origin Policy Explained

Serialization Bugs Explained

A Security-focused HTTP Primer

Vulnerability Database Resources

Assorted

My Information Security Blog Posts

Information Security Definitions

The Difference Between Threats, Vulnerabilities, and Risks

How to Build a Successful Information Security Career

The Birthday Attack

Information Security Interview Questions

Encoding vs. Encryption vs. Hashing

Diffie-Hellman Explained

The Difference Between the Internet, the Deep Web, and the Dark Web

—

Subscribe for one coffee a month ($5) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month.

April 13, 2019

Unsupervised Learning: No. 173

Unsupervised Learning is my weekly show that provides collection, summarization, and analysis in the realms of Security, Technology, and Humans.

It’s Content Curation as a Service…

I spend between five and twenty hours a week consuming articles, books, and podcasts—so you don’t have to—and each episode is either a curated summary of what I’ve found in the past week, or a standalone essay that hopefully gives you something to think about.

Subscribe to the Newsletter or Podcast

Become a member to get every episode

April 11, 2019

The Difference Between Classical Liberalism and Libertarianism

I recently wrote a well-received piece about the political positions of the Intellectual Dark Web (IDW), and a ferocious discussion erupted in the comments regarding Dave Rubin‘s political philosophy.

To a modern liberal, Libertarian basically means someone who cares only about themselves.

Rubin calls himself a Classical Liberal, but it turns out that people on Twitter and Reddit aren’t sure exactly what that means. Rubin himself says he’s undergone a Conservative Transformation lately, leading many liberals to claim he’s simply become a Libertarian. Meanwhile, Libertarians are saying those are completely different things.

I was confused myself.

A cursory look at the definitions of Classical Liberalism and Libertarianism had them looking nearly identical. So I decided to do a deep dive on the differences. Here’s what I found, combined with my analysis of the situation.

Classical Liberalism was a strong counter to previous political movements that placed authority in the hands of churches, monarchs, or governments. Its central theme was the freedom of individuals rather than central authorities, and the idea was spawned by a number of original thinkers like Adam Smith, John Locke, and others as a response to the industrial revolution and population growth in the late 1800s.

Social Liberalism and Conservatism emerged from Classical Liberalism in the early 20th century.

Classical liberalism is the philosophy of political liberty from the perspective of a vast history of thought. Libertarianism is the philosophy of liberty from the perspective of its modern revival from the late sixties-early seventies on.

Mario Rizzo

Social Liberalism focused on having the government still manage much of the economy, but with more social freedoms.

Conservatism focused on the government still upholding traditional social norms, but allowing economic freedoms—especially regarding the use of free markets.

Libertarianism is a strong form of Classical Liberalism that argues that individuals should be left alone—without much influence from central government, and that personal responsibility is the most powerful ingredient of success. Pure Libertarians believe the government should stay out of both social and economic issues, meaning they tend to offend both Social Liberals and Conservatives, for opposite reasons.

My analysis within today’s context

Over the last week or so I watched a ton of Dave Rubin videos, and what I found will likely upset readers both on the left and the right.

First, I don’t think Rubin is being academically or politically accurate in branding himself as a Classical Liberal. And from what I’ve seen, he isn’t actually claiming this.

Dave is a bit confused right now, but you probably would be too if you were gay, Jewish, previously liberal, and were currently going through a conservative awakening.

He’s not a Conservative in the common use of the word, and he doesn’t want to use the term Libertarian because it has negative connotations. So I think he’s reached back into history for a loftier-sounding synonym that doesn’t make him feel as uncomfortable.

I make an argument here that the IDW is basically a collection of upset liberals looking for honest conversation.

If you think it’s not possible for a Trump supporter to be confused rather than evil, then you’re not listening closely enough.

That’s the part that will upset readers on the right. The part that will upset readers on the left is that I’ve yet to find evidence of actual hatred or malice in his videos. Yes, he gives props to Trump—who I cannot stand—and yes, he’s all over the place on healthcare and climate change. But to me he is behaving exactly like a liberal with a severe case of PTSD—not like an evil or hateful person. I see him as good-natured and wrong, which is much different than someone like Rush Limbaugh or Trump.

Rubin is using “Classical Liberalism” because it gives liberals a tiny moment of confusion before they attack, but it’s really just new packaging for his individual—and very fluid—brand of Libertarianism.

In short, “Classical Liberalism” is being used by some on the right today as a somewhat pseudo-intellectual way of claiming that their unwillingness to use government and shared resources to help the ailing and unfortunate masses is somehow a superior policy because 1), the phrase is old, 2) because the “liber” in Classical Liberalism (insert Kung-fu here) means freedom.

(eagle sound)

So it’s not that they’re selfish—it’s just that they value freedom from government more than they value helping people they don’t know (and who should be helping themselves anyway).

But don’t call them Libertarians.

Summary

Classical Liberalism was originally a break away from churches, monarchies, and powerful and prescriptive governments—with a counter-focus on freedom of the individual.

Both Liberalism (social freedoms and equality) and Conservatism (economic freedoms and free markets) came from Classical Liberalism.

Libertarianism—in its pure form—is about freedoms from any sort of central authority, and thus goes against both conservatives and liberals.

In some universe, there might be a difference in Rubin’s Classical Liberalism and today’s Libertarianism, but in 2019 in this universe—there isn’t one.

Notes

I created the diagram myself using my own hybrid paraphrasings of multiple definitions across multiple sources. Because meanings change so quickly, and because we’re in the midst of such a quick change right now, I felt I needed to take that (ahem) liberty. When I tried to use more formal definitions they lacked clarity, concision, and/or context. If you’re a Political Science expert (I’m not) and I’ve offended your profession, please tell me how I can tweak them to be more accurate.

For the record, I know many good-hearted Libertarians and Conservatives. Just because I think this particular strain of wordsmithing is bankrupt doesn’t mean I think there’s no merit to any of these anti-government arguments.

Don’t start with the anti-progressive/modern liberal stuff here. That’s a separate argument to be had in a separate thread. This one is just about the definition of Classical Liberalism.

SOURCE: https://www.sciencedaily.com/terms/cl...

SOURCE: https://thinkmarkets.wordpress.com/20...

—

Subscribe for one coffee a month ($5) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month.

April 9, 2019

Unsupervised Learning: No. 172 (Member Edition)

This is a Member-only episode. Members get the newsletter every week, and have access to the Member Portal with all existing Member content.

Non-members get every other episode.

or…

—

Subscribe for one coffee a month ($5) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month.

April 6, 2019

A Visual Breakdown of Intellectual Dark Web (IDW) Political Positions

I realized recently that I had no idea where many people in the Intellectual Dark Web actually stood on key positions. I thought I knew—sort of—but it turns out that most of what I knew was coming from a shoddy skyscraper of misconceptions.

I was being attacked by alt-right types saying DiResta part of a pro-Clinton conspiracy.

I did a post recently about Renée DiResta being on Joe Rogan’s podcast, and in the comments I learned that she was evidently some sort of shill for…I’m not sure who. I guess for the Democrats? I also learned recently from other readers that Joe Rogan was alt-right.

Really? Joe Rogan? A conservative? The mediation, cannabis, commedian who’s for gay marriage and pro-choice, and income equality? I then made the mistake of thinking Dave Rubin was conservative as well, since he’s often labeled that by the extreme left. I’m an MMA fan, and I have followed Sam Harris since the very beginning, so Rogan and Harris were already in my awareness and thus I could tell when they were being maligned fairly easily. But when it came time for me to describe people like Rubin, I realized I was committing the same errors as everyone else.

If you’ve not listened to a large body of someone’s work—both in good faith and over a long period of time—you can’t hope to understand them.

Sam is half Jewish.

So I decided this weekend to do the research to figure out what these people believed on all the major issues, and that’s the spreadsheet you see above.

During the research I started noticing some weird stuff about this supposedly hateful IDW group of Harris, Weinstein, Rubin, and Shapiro. Namely, they’re all Jewish, and yet a number of them are often labeled as white supremacists and even neo-Nazis. That completely breaks the supidmeter.

Ben Shapiro—yes, the conservative one—actually needs private security because of his open criticism of the alt-right. Shapiro has also been in very aggressive debates with Milo Yiannopoulos, who is a vocal proponent of the alt-right, and that public disagreement has become quite ugly.

Then I watched Dave Rubin, who a bunch of my liberal friends told me was this crazy right-wing guy, have Shapiro on to debate the top liberal vs. conservative issues. And Rubin (a gay Jew, by the way), was the one defending the liberal side.

And just yesterday I heard one of the most encouraging and heart-warming discussions I’ve heard in a long time between Joe Rogan and Ben Shapiro, where Rogan (gasp) takes the liberal positions and Ben debates from the conservative side. And in both cases (Rubin and Rogan) the conversation was civil and productive.

Peterson is something of an exception here.

If you look at the chart I made at the top of this piece, you can see that almost everyone is extremely liberal—including people like Rogan.

Their binding factor—which is what brings Shapiro into the mix—is that they’re willing to have good faith conversations with people they disagree with.

And I think that’s glorious. You really should watch the recent podcast with Joe and Ben. It’s an unbelievably refreshing conversation between two people who greatly disagree about fundamental things.

Summary and takeaway

I can’t quite figure Peterson out, so I’m withholding judgment on that one.

With the exception of Ben Shapiro, who is super libertarian and doesn’t want to impose his religious ideas upon you through government—and Jordan Peterson, who seems to constantly send mixed signals to me, the vast majority of people in the IDW are extremely liberal on all of the core issues like abortion, climate change, gay marriage, etc.

They’re not neocons, they’re not alt-right, and they’re not racists. They’re the opposite of that, actually, and the main thing they have in common is the desire to preserve and amplify good-faith conversation.

Rather than bash them due to something you heard from this one place—or that one friend—take the time to actually listen. Most of them are progressive just like you and me. And if you’re not liberal that’s fine too—listening will show you that true discussion is still possible.

Either way, I urge you to join us in resisting the urge to shut down difficult conversation, because that’s precisely what creates the empty stage that empowers the alt-right.

Notes

Apr 6, 2019 — I reached out to Sam and updated the sheet to mark him as fully pro on single-payer healthcare. He also suggested adding Wealth Inequality as a topic, which I did.

Apr 6, 2019 — I corrected Eric’s name, where I had Bret initially. Although Bret is also a member as well as far as I can tell.

Apr 6, 2019 — It seems Rubin has/is shifting ever more right, so it’s hard to know how much of his liberal stances remain, but as of the publish date this is what I still have for his positions on these topics. And that still puts him quite liberal.

Here is Ben Shapiro heavily criticising the alt-right. Link

For the table at the top I basically spent many hours going to find where each person stood on those key issues. It really needs to be sourced to be most useful, so I’m going to be collecting each source in the Google Spreadsheet I used for collection. If anyone wants to help collect, or even add more positions to make the chart better, here’s the sheet. Link

—

Subscribe for one coffee a month ($5) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month.

April 1, 2019

Unsupervised Learning: No. 171

Unsupervised Learning is my weekly show that provides collection, summarization, and analysis in the realms of Security, Technology, and Humans.

It’s Content Curation as a Service…

I spend between five and twenty hours a week consuming articles, books, and podcasts—so you don’t have to—and each episode is either a curated summary of what I’ve found in the past week, or a standalone essay that hopefully gives you something to think about.

Subscribe to the Newsletter or Podcast

Become a member to get every episode

Security News

Mastercard is looking to create a Digital ID service that can bind your digital presence to your mobile device, which will be able to verify you to various services. Link

Palantir has won an $800 million contract to build the next combat intelligence system (to replace DCGS-A) for the Army. Link

Putin appears to be causing brain drain in Russia. Link

Dropbox has an interesting proposal for improving vendor security assessments. TL;DR: They turned their requirements into contractual points. LOVE IT. Link

The US Military is working on software to detect “micro changes” in people with top security clearances, and many think it’s the future of employee monitoring as well. Link

Airbnb says it’s going after hosts that record their guests, but what about guests who drop cameras in host properties? Seems like people with nice places would be more lucrative for blackmail and such. I wonder if this is part of threat model. Link

Verizon has opened access to the free version of its spam and robocall blocking tool based on STIR/SHAKEN. I can’t wait for the other carriers to get this. Link

The Air Force is working on unmanned AI combat drones, in a project called Skyborg. Link

The BSidesSF 2019 Videos Playlist Link

Advisories: Cisco IOS XE , Cisco WebEx Browser Extension

Breaches: Toyota

⚙️ Technology News

Amazon has released S3 Glacier Deep Archive, which is rare-access data storage for just $1/TB/month. Link

Daimler is investing heavily in a self-driving tech company focused on Level 4 Self-driving Trucks. Link

RSS and The Matrix were born 20 years ago, in the same month. Link

Daniel Miessler's Blog

- Daniel Miessler's profile

- 18 followers