Daniel Miessler's Blog, page 83

May 29, 2019

Thinking of Deepfakes as Malicious Advertising

With global leaders the implications are potentially severe

Someone released a video recently that seemed to show Nancy Pelosi slurring and mangling her speech. The video spread virally in right-leaning circles, but it soon turned out to be fake.

I commented on this in my most recent newsletter, saying:

What this shows us is that it’s not the machine learning that makes Deepfakes dangerous; it’s the willingness of a massive percentage of the US population to believe total garbage without an ounce of scrutiny.

Unsupervised Learning, No. 179

But a reader on Twitter named David Scrobonia had an even more interesting point about this.

This is a really interesting point about deepfakes.

— Daniel Miessler ☕

Seeing them can detonate in your brain and affect your emotional view of the subject, even if your logical brain learns/knows it’s false.

That’s the same mechanism as advertising, i.e., target the emotions, not the logic. https://t.co/VrPlV7Defa

May 28, 2019

The Unsupervised Learning Newsletter

There is also a podcast version of the newsletter.

.errordiv { padding:10px; margin:10px; border: 1px solid #555555;color: #000000;background-color: #f8f8f8; width:500px; }#advanced_iframe {visibility:visible;opacity:1;}#ai-layer-div-advanced_iframe p {height:100%;margin:0;padding:0}

My ~12 hours of research gets consolidated into 20 minutes of content!

See you for the next issue!

Best,

—

Become a direct supporter of my content for less than a latte a month ($50/year) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month, plus access to the member portal that includes all member content.

Unsupervised Learning: No. 179

Unsupervised Learning is my weekly show that provides collection, summarization, and analysis in the realms of Security, Technology, and Humans.

It’s Content Curation as a Service…

I spend between five and twenty hours a week consuming articles, books, and podcasts—so you don’t have to—and each episode is either a curated summary of what I’ve found in the past week, or a standalone essay that hopefully gives you something to think about.

Subscribe to the Newsletter or Podcast

Become a member to get every episode

May 24, 2019

Unsupervised Learning: No. 178 (Member Edition)

This is a Member-only episode. Members get the newsletter every week, and have access to the Member Portal with all existing Member content.

Non-members get every other episode.

or…

—

Become a direct supporter of my content for less than a latte a month ($50/year) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month, plus access to the member portal that includes all member content.

May 23, 2019

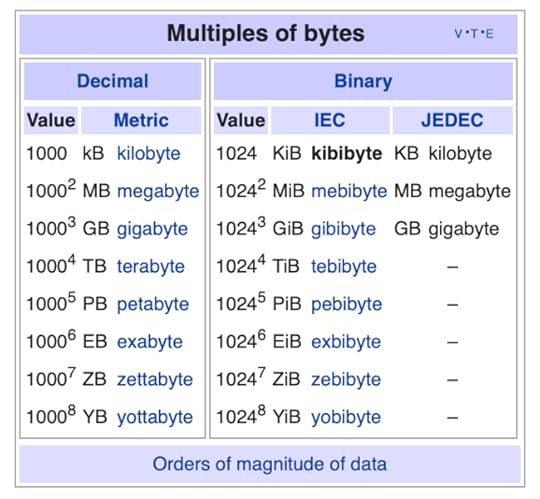

The Difference Between Kilobytes and Kibibytes

I’ve been in the industry for over 20 years, and I’m just now learning this. I knew there was a disturbance in the force, but it was never enough of an issue to investigate.

Anyway. Basically, there are two ways of using Kilx within computer sizing of things.

Multiplying by 1000, as in 1000 bytes = 1 kilobyte

Using binary with an exponent of 10, like 210, which is 1024, not 1000

And depending on which you use, you’ll get different sizes. And that’s why we’ve often seen disappearing sizes in real life compared to advertisements—they were using the large number instead of the little one!

TL;DR

A kilo is 1000.

A kibi is 1024.

The world is a strange place.

Notes

The Wikipedia article on kibibyte. More

—

Become a direct supporter of my content for less than a latte a month ($50/year) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month, plus access to the member portal that includes all member content.

May 22, 2019

Grit is the Ultimate Privilege

The internet is in the middle of a turbulent discussion about privilege—including what the privileges are, who has them, and what can be done to equalize things.

Examples of privileges include being of a culturally-dominant race, having rich parents, having well-connected friends, living in large and/or coastal cities, etc.

The basic argument is that those who have achieved greatly often don’t deserve what they’ve achieved because they were part of one or more privileged groups. And, conversely, it’s not ok to blame people who are in non-privileged groups for not succeeding because they didn’t have the same advantages.

As someone who doesn’t believe in free will, I am largely on-board with this argument. The no-free-will line says that we are products of our genetics and our environments, and that because we don’t have control of either of those, we cannot be in control of outcomes. And the same goes for human outcomes such as education and financial success.

Where I differ from some making the privilege argument is in regard to next steps, and in hopefully not being confused about the causal relationship between the participating variables.

Indian Americans are the most successful group of Asians in America today.

When you look at that most successful groups in America today, Americans of Asian descent show as the clear winners—far surpassing whites in education attained, money earned, and a number of other standard indicators.

And when these groups are studied, one of the primary things that sets them apart is their home life, their upbringing, and the self-discipline instilled in them by their extremely present, helicoptering, and success-driven parents. In a word, Asian Americans that succeed are heavily imbued with grit.

There is much discussion about the word grit, and what it means, but a common thread in the conversation always reduces to delaying gratification. A very early study showed that children who could delay eating marshmallows that were in front of them, to get more later, ended up doing better in life than those who could not control themselves.

And a number of other studies have shown that grit is even more important than IQ in determining future success.

So that brings us to the question. If grit determines who does well in school, and therefore who gets the good jobs, and has the stable families, and achieves financial success, then where does it come from? Is it nature or nurture? As it turns out, it doesn’t really matter. Either way it will come down as a privilege in today’s parlance.

Congratulations on picking your tiger parents.

If it’s genetic, then you got lucky by being whatever lineage that gave you a lot. And if it’s upbringing, then you got lucky by picking your parents well.

Billionaires fund schools in low-income areas, for example.

So how do we equalize that? With other privileges it seems more straightforward. If it’s a dominant racial group, or a lucky trust-fund kid, it seems fairly clear why people are asking for reparations to be made. The one group just gives money to the other group so it can then be equalized, and we move on towards eventual equality.

But with grit the situation is much more complex. With grit we’re saying it’s not a matter of current financial situation that makes the difference. Many of these Asian families producing the best-performing kids in high-school and university come from the worst neighborhoods, and the top academic achievements in bad communities almost always go to Asians.

In other words, if the most powerful privilege is actually self-discipline—which comes from a strict, two-parent family upbringing that’s focused on academic and extra-curricular performance—how are we supposed to give that to other groups that don’t have it?

It seems both the left and right responses to this are oblivious. The right says, “Exactly! It’s all about work ethic! So if you don’t have it, that’s your own fault, and you deserve to suffer!” And the left says, “No, it’s not work ethic, it’s bad families, and oppression, and racism, all caused by those who have other kinds of privilege.”

But neither of these approaches helps anyone. The right is wrong because it’s foolish to reward and punish people for things they didn’t choose (genetics, parents, environment, etc.), and the left is wrong because blaming people with high self-discipline for the suffering of those with low self-discipline is a losing battle that only moves people towards the right.

It seems clear to me that the path forward is to identify grit as a top-tier marker of success, and work to optimize people, families, and communities for maximizing it. That will require ideas from the left, the right, and from new places outside our current political models.

The ultimate privilege—that yields the greatest rewards over time—is self-discipline. And if we want to help the most people possible, have the maximum amount of personal responsibility possible, which ultimately leads to less suffering and more human flourishing, that’s the thing we need to focus on improving.

Notes

This essay does not assume, as many on the right do, that systemic racism and sexism have been adequately solved, and that it’s time to put it all behind us. What I’m doing here is saying that the fastest way for those suffering from those things is to develop grit in themselves, their families, and their communities. But we absolutely need to continue the battle against external causes of disparity as well. That work has seen tremendous progress, but it is not done.

—

Become a direct supporter of my content for less than a latte a month ($50/year) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month, plus access to the member portal that includes all member content.

May 14, 2019

Unsupervised Learning: No. 177

Unsupervised Learning is my weekly show that provides collection, summarization, and analysis in the realms of Security, Technology, and Humans.

It’s Content Curation as a Service…

I spend between five and twenty hours a week consuming articles, books, and podcasts—so you don’t have to—and each episode is either a curated summary of what I’ve found in the past week, or a standalone essay that hopefully gives you something to think about.

Subscribe to the Newsletter or Podcast

Become a member to get every episode

May 12, 2019

Summary: The Tyranny of Metrics

8/10

My One-Sentence Summary

Content Extraction

Takeaways

My book summaries are designed as captures for what I’ve read, and aren’t necessarily great standalone resources for those who have not read the book.

Their purpose is to ensure that I capture what I learn from any given text, so as to avoid realizing years later that I have no idea what it was about or how I benefited from it.

My One-Sentence Summary

While metrics can and do offer extraordinary benefits when they’re used carefully and properly, there is significant chance of them being chosen incorrectly, being gamed and corrupted by various parties, and ultimately becoming toxic to the very cause they were created to help.

Content Extraction

Empower others, but be willing to step in with micromanagement temporarily if things get out of hand

Don’t be so dominating and intimidating that your leaders can’t step up and lead themselves

Discipline is great, but too much leads to a lack of creativity

Too much creativity and not enough discipline leads to sloppiness and mistakes

The more a quantitative metric is visible and used to make important decisions, the more it will be gamed—which will distort and corrupt the exact processes it was meant to monitor.

An adaption of Campbell’s Law

And the second is a similar, more simplified version of the same, by Goodhart:

Anything that be measured and rewarded will be gamed.

An adaption of Goodhart’s Law

All quotes here are from the book itself unless otherwise indicated.

“The three components of great training are realism, fundamentals, and repetition.”

Metrics can be and often are useful, but the thing to avoid is Metrics Fixation, which is where you replace judgement with numeric indicators, you think making metrics public will solve everything through motivation, and thinking that the best way to motivate people is by giving them money or ordinal rankings.

I’m not convinced this is true in theory, but it’s definitely true in practical terms given current society and technology.

Not everything that matters is measurable

Not everything that’s measurable matters

Common flaws

The most characteristic feature of metric fixation is the aspiration to replace judgment based on experience with standardized measurement.

Muller, Jerry Z.. The Tyranny of Metrics (p. 6). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

A common flaw is measuring what’s easiest

You don’t want to measure the simple, when the outcome you want is complex

Measuring inputs rather than outputs

Gaming through creaming is when you find simpler targets or only choose inputs where you’re likely to have good metrics

Lowering standards to have more successes

Leaving out data or reclassifying incidents as higher or lower categories

Outright cheating happens too, when the pressures are high enough (high Metrics Fixation)

The demand for measured accountability and transparency waxes as trust wanes.

Muller, Jerry Z.. The Tyranny of Metrics (p. 39). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Takeaways

Metrics are a good way to align a team around a goal.

The more numeric, visible, and reward-tied a metric is, the more likely it is to be gamed and turn toxic to its original purpose.

When you use a metrics program, be sure to periodically ensure that undesired externalities have not emerged as a result. And be prepared to go digging, since the negative effects could be well-hidden.

Moderation is key. Use metrics, but don’t let them control you or become a substitute for judgment.

Remember to constantly revisit the spirit of what you’re trying to attain, and continuously ask yourself whether the tangible things you’re tracking are high-signal proxies for those goals.

You can find my other book summaries here.

Notes

There is a previous book by the same two guys, called Extreme Ownership, and while it was good, it did emphasize the extremes of each point that was made. This book corrects that by focusing everything on the balances that have to be constantly adjusted for the situation. This is basically the better version of the first book, but you can still benefit from the first one as well.

—

Become a direct supporter of my content for less than a latte a month ($50/year) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month, plus access to the member portal that includes all member content.

May 10, 2019

Examples of Bad Metrics

There are myriad books and websites describing the Top N Metrics in a particular area, but very few tell you what not to do. This article will show you specific examples of metrics gone bad, what’s wrong with them, and what you can do to make them better.

Economic as in economics, not financial.

First, it’s important to understand the philosophical and economic downside of metrics systems. The book, The Tyranny of Metrics, by Jerry Z. Muller does a great job of capturing the issue.

The book talks about a couple of thinkers who called out the dangers of over-indexing on metrics with two related laws. First is Campbell’s Law:

The more a quantitative metric is visible and used to make important decisions, the more it will be gamed—which will distort and corrupt the exact processes it was meant to monitor.

An adaption of Campbell’s Law

And the second is a similar, more simplified version of the same, by Goodhart:

Anything that be measured and rewarded will be gamed.

An adaption of Goodhart’s Law

Basically, the more visible, quantifiable, and important a metric is, the more it’s vulnerable to gaming and toxicity to its initial purpose.

But neither the author of this book, nor I, are saying to avoid metrics, or that they’re inherently harmful. We’re simply saying that you need to avoid metrics worship, or what Muller calls, “Metrics Fixation”.

As with so many important things in life, the key is balance—in this case between measurement and judgment. We can and should use metrics where appropriate, but we can’t allow them to turn into a religion.

Examples of real-world metrics gone bad

Economics is critical because it’s about understanding how policy changes have both desired effects and externalities.

The best way to illustrate this problem is to give examples of bad metrics that produced unwanted outcomes. Here are some of the most cringe-smile invoking examples.

Number of poisonous snakes

What we’re trying to avoid is Metrics Fixation.

A leader in India said too many people were dying from poisonous snakes, so he offered money to anyone who brought him a dead one.

Unintended Negative Result: People started breeding poisonous snakes in private, so they could kill them and bring them to the government.

A Better Metric: Reward people for a fewer number of deaths being reported from poisonous snakes. But realize that this can—and likely will—cause additional effects (like people being paid to classify snakebite deaths as something else).

Stop taking hard cases

Surgeons are often judged by how often there are complications or deaths in their surgeries, which affects their marketability and insurance rates.

Unintended Negative Result: Many surgeons stop taking high-risk or complicated cases, which results in people who really need help getting inferior care.

A Better Metric: Incorporate a rating of difficulty, risk, or complication in the calculation, and maybe even incentivize the courage to take on hard cases.

Teaching to the test

Governments in the last couple of decades have focused on making sure more students can hit a minimum level of competency in subjects such as English and Math.

Unintended Negative Result: Many schools have taken this to an extreme, and basically spend all their classroom time teaching to the test, which results in no freedom, enthusiasm, and ultimately a loss of curiosity and creativity in the students.

A Better Metric: Find ways to encourage creativity and curiosity, as well as wrote learning, since those are a big part of what we’re trying to foster in our children as a springboard for life-long learning.

Additional metrics that directly violated their purpose

Chinese peasants used to be paid for finding dinosaur bones, but this actually lead to them breaking every bone they found into multiple pieces so they could be paid multiple times.

Security managers prioritizing bug volume rather than bug quality, leading to more bugs that don’t matter and them spending less time on the ones that matter.

Salespeople being rewarded based on number of leads, which often creates tons of poor, unqualified leads that take up quality time that should have been spent elsewhere.

Wells Fargo massively incentivized the metric of “new accounts”, which caused them to set up thousands of fake accounts, ultimately resulting in major lawsuits and financial impact.

A number of governments with air pollution problems have started alternating which cars can be on the roads each day by even and odd license plate numbers, which unfortunately led many to buy an additional vehicle so they could drive every day.

Manufacturing workers being told “reported incidents WILL go down”, which doens’t mean necessarily that less people will get hurt, but that if they do get hurt they should find a way to avoid reporting it.

Glass plant workers were told to produce as many square feet of sheet glass as possible, and soon started making it so thin that it wasn’t usable for anything.

The mortgage loan situation is great example of a good-natured metric causing great harm.

Before the mortgage crisis of 2008, many banks were given metrics for loans to non-traditional borrowers (people who couldn’t normally qualify for a mortgage), and the result was billions in loans that couldn’t be paid back.

Discussion

There’s a similar example in the problem of teaching AI what to value if it becomes sentient and super-intelligent. You can’t be too specific or you could cause great harm.

For me the key here is that metrics should 1) tell us the state of the world we care about, and 2) track spiritually to what we desire as opposed to technically. Great examples of that were seen above, where we thought this quantatative, visible metric got us what we wanted, when in fact we wanted something broader and more difficult to describe.

Another example of this comes from Daniel Kahneman’s research on happiness, where he argues that it’s not happiness people are looking for, but rather satisfaction that their lives are going well in the long-term.

If we were to measure smiles, for example, as a proxy for happiness, how would that track with satisfaction? It’s those disconnects between the measured and that which we truly care about that are crucial to avoid in any metrics program.

Many argue that metrics have eaten standardized edudcation.

The other thing to avoid is having the entire measurement effort metastasize into a tumor that eats the organization. Possible solutions there could include hard limits on the number of metrics, the time allowed to be spent on them, and/or the budget for running the program. As Muller points out, organizations with high turnover and a lack of direction could confuse metrics with leadership and do little else.

Summary

Metrics are a good way to align a team around a goal.

The more numeric, visible, and reward-tied a metric is, the more likely it is to be gamed and turn toxic to its original purpose.

When you use a metrics program, be sure to periodically ensure that undesired externalities have not emerged as a result. And be prepared to go digging, since the negative effects could be well-hidden.

Moderation is key. Use metrics, but don’t let them control you or become a substitute for judgment.

Remember to constantly revisit the spirit of what you’re trying to attain, and continuously ask yourself whether the tangible things you’re tracking are high-signal proxies for those goals.

—

Become a direct supporter of my content for less than a latte a month ($50/year) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month, plus access to the member portal that includes all member content.

Examples of Metrics That Incentivize the Wrong Behaviors

There are 39,231 websites out there telling you the Top N metrics, but very few offer tangible instances of what not to do. This article will show you specific examples of metrics gone bad, why they’re not helpful (or worse), and what you can do to make them better.

Economic as in economics, not financial.

First, it’s important to understand the philosophical and economic downside of metrics systems. The book, The Tyranny of Metrics, by Jerry Z. Muller does a great job of capturing the issue.

The book talks about a couple of thinkers who called out the dangers of over-indexing on metrics with two related laws. First is Campbell’s Law:

The more a quantitative metric is visible and used to make important decisions, the more it will be gamed—which will distort and corrupt the exact processes it was meant to monitor.

An adaption of Campbell’s Law

And the second is a similar, more simplified version of the same, by Goodhart:

Anything that be measured and rewarded will be gamed.

An adaption of Goodhart’s Law

Basically, the more visible, quantifiable, and important a metric is, the more it’s vulnerable to gaming and toxicity to its initial purpose.

But neither the author of this book, nor I, are saying to avoid metrics, or that they’re inherently harmful. We’re simply saying that you need to avoid metrics worship, or what Muller calls, “Metrics Fixation”.

As with so many important things in life, the key is balance—in this case between measurement and judgment. We can and should use metrics where appropriate, but we can’t allow them to turn into a religion.

Examples of real-world metrics gone bad

Economics is critical because it’s about understanding how policy changes have both desired effects and externalities.

The best way to illustrate this problem is to give examples of bad metrics that produced unwanted outcomes. Here are some of the most cringe-smile invoking examples.

Number of poisonous snakes

What we’re trying to avoid is Metrics Fixation.

A leader in India said too many people were dying from poisonous snakes, so he offered money to anyone who brought him a dead one.

Unintended Negative Result: People started breeding poisonous snakes in private, so they could kill them and bring them to the government.

A Better Metric: Reward people for a fewer number of deaths being reported from poisonous snakes. But realize that this can—and likely will—cause additional effects (like people being paid to classify snakebite deaths as something else).

Stop taking hard cases

Surgeons are often judged by how often there are complications or deaths in their surgeries, which affects their marketability and insurance rates.

Unintended Negative Result: Many surgeons stop taking high-risk or complicated cases, which results in people who really need help getting inferior care.

A Better Metric: Incorporate a rating of difficulty, risk, or complication in the calculation, and maybe even incentivize the courage to take on hard cases.

Teaching to the test

Governments in the last couple of decades have focused on making sure more students can hit a minimum level of competency in subjects such as English and Math.

Unintended Negative Result: Many schools have taken this to an extreme, and basically spend all their classroom time teaching to the test, which results in no freedom, enthusiasm, and ultimately a loss of curiosity and creativity in the students.

A Better Metric: Find ways to encourage creativity and curiosity, as well as wrote learning, since those are a big part of what we’re trying to foster in our children as a springboard for life-long learning.

Additional metrics that directly violated their purpose

Chinese peasants used to be paid for finding dinosaur bones, but this actually lead to them breaking every bone they found into multiple pieces so they could be paid multiple times.

Security managers prioritizing bug volume rather than bug quality, leading to more bugs that don’t matter and them spending less time on the ones that matter.

Salespeople being rewarded based on number of leads, which often creates tons of poor, unqualified leads that take up quality time that should have been spent elsewhere.

Wells Fargo massively incentivized the metric of “new accounts”, which caused them to set up thousands of fake accounts, ultimately resulting in major lawsuits and financial impact.

A number of governments with air pollution problems have started alternating which cars can be on the roads each day by even and odd license plate numbers, which unfortunately led many to buy an additional vehicle so they could drive every day.

Glass plant workers were told to produce as many square feet of sheet glass as possible, and soon started making it so thin that it wasn’t usable for anything.

The mortgage loan situation is great example of a good-natured metric causing great harm.

Before the mortgage crisis of 2008, many banks were given metrics for loans to non-traditional borrowers (people who couldn’t normally qualify for a mortgage), and the result was billions in loans that couldn’t be paid back.

Summary

Metrics are a good way to align a team around a goal.

The more numeric, visible, and reward-tied a metric is, the more likely it is to be gamed and turn toxic to its goal.

When you use a metrics program, be sure to periodically ensure that undesired externalities have not emerged as a result. And be prepared to go digging, since they’ll often be secretive.

Moderation is key. Use metrics, but don’t let them control you or become a substitute for judgement.

—

Become a direct supporter of my content for less than a latte a month ($50/year) and get the Unsupervised Learning podcast and newsletter every week instead of just twice a month, plus access to the member portal that includes all member content.

Daniel Miessler's Blog

- Daniel Miessler's profile

- 18 followers