Daniel Miessler's Blog, page 131

February 7, 2017

It’s the People, Stupid

Imagine you have decided to spend your life evangelizing healthy eating.

And then imagine that you happen upon a population that does nothing but scream out constantly for candy, sugar, and cake.

We want cake! We want cake! We love sugar. We want sugar!

Day in and day out, that’s what the people yell. And it’s all they’ll eat. You show up to their rallies with whole breads and vegetables and you are lucky if you’re ignored.

Then one day a leader emerges in the ranks. A man who claims to have the most candy of anyone. And the most cakes.

Everyone deserves sweet foods! They’ll not force their nuts and grains upon us!

He becomes wildly popular, and is elected president.

When the healthy eaters hear about this they’re appalled.

How can this president say these things about sugar being good for you? How can he say that wheat bread is for unsuccessful people? How can he say that vegetables are for gays?

They assemble. They hold rallies. They protest. Everyone is furious with him. He’s evil, they say. He’s breaking everything, they say.

Except he’s not the problem.

He could not exist without millions of people chanting for tooth decay. He could not exist without people casting votes for diabetes and heart disease.

Without the people, he would be a clown selling candy. But with people who like clowns and candy, he’s an absolute celebrity, and indeed the savior of the sweet world.

It’s a silly story, but the concept is maps clearly onto reality.

People are infuriated with what Trump is doing, but they are ignoring the fact that roughly half the country is still supporting him. They like what he’s doing. 5/5—would elect again.

You keep attacking Trump, but he’s not the issue. The issue is around 180 million dumb people who don’t read books, don’t trust evidence, and can be convinced of anything that makes them feel good emotionally.

Fix that and you fix Trump. Don’t fix that and there will be 1,000 Trumps lined up behind him when he’s gone.

In democracies it’s not the leaders’ fault. If you want to affect change, get the people to read some history and science. If you can’t do that then it doesn’t matter what you say about the leader. You’re attacking symptoms rather than diseases.

It’s the people, stupid.

Notes

I am quite aware that there were good reasons to vote for Trump, and that some small percentage of people might have used those reasons when they did so. But they’re the minority. Besides, the issue also applies to impotent, feel-good liberals who don’t affect positive change. It’s the same problem on both sides; the situation with Trump is just particularly acute.

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

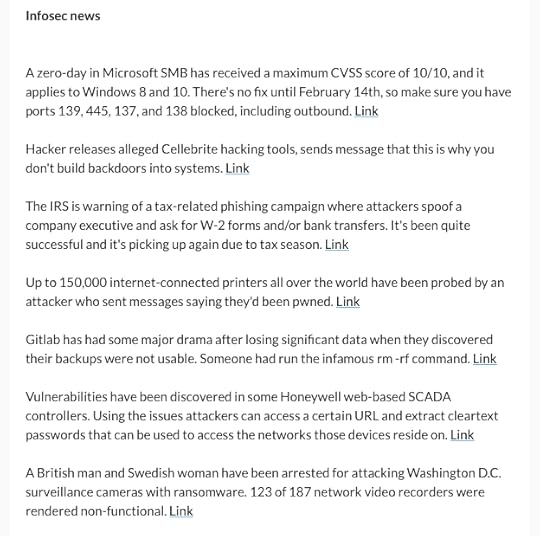

Unsupervised Learning: No. 64

This week’s topics: Tax phishing, Microsoft SMB vulnerability, Cellebrite tools released, Computer interfaces, Mobile 2.0, new projects, more…

This is Episode No. 64 of Unsupervised Learning—a weekly show where I curate 3-5 hours of reading in infosec, technology, and humans into a 15 to 30 minute summary.

The goal is to catch you up on current events, tell you about the best content from the week, and hopefully give you something to think about as well.

The show is released as a Podcast on iTunes, Overcast, Android, or RSS—and as a Newsletter which you can view and subscribe to here or read below.

Click the image to read the full newsletter.

Thank you for listening, and if you enjoy the show please share it with a friend or on social media.

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

February 5, 2017

An Exploration of Human to Computer Interfaces

I read and think a lot about how humans interact with computers, and what that interaction will look like at various points in the future.

I was going to call this a hierarchy of human to computer interfaces, but quickly realized that it’s not a hierarchy at all. To see what I mean, let’s explore them:

Input interfaces

This is what most think of when they think “interface”, i.e. how you interact with the computer.

Manual Physical Interaction: original key-based keyboards, physical switches, etc.

Manual Touchscreen Interaction: smartphones, tablets, etc.

Natural Speech: Voice: Siri, Google Assistant, Alexa

Natural Speech: Text: messaging, chatbots, etc.

Neural: You think, it happens. No mainstream examples yet exist.

Output interfaces

A key part of that interaction, however, is how the computer returns content or additional prompts to the human, which then leads to additional inputs.

Physical or Projected 2D Display: standard computer monitor, LCD/LED display, projectors, etc.

Physical or Projected 3D Display: augmentation of vision using glasses, or projection effects that emulate three dimensions.

Audible: The computer tells you its output.

Neural Sensory: You “see” or “hear” what’s being returned, but it skips your natural hardware of eyes and ears.

Neural Direct: You receive the understanding of having seen or heard that content, but without having to parse the content itself (NOTE: I’m not sure if this is even possible).

Technology limitations vs. medium limitations

Given our current technology levels, we’re still working with Manual Touchscreen Interaction and Display output for the most part, and we’re just starting to get into Voice input and output.

But like I mentioned above, this isn’t a linear progression. Voice isn’t always better than visual displays for displaying information to humans, or even for humans giving input to the computers.

Benedict Evans has a great example:

@Rotero try choosing a flight on the phone

— Benedict Evans (@BenedictEvans) February 5, 2017

My favorite example is Excel. Imagine working with a massive dataset like so:

Read row one-thousand forty-three, column M…

…and your dataset has 300 thousand rows and 48 columns. Seeing matters in this case, and voice might be able to help in some way, but it won’t replace the visual. It simply can’t because of bandwidth limitations. When you look at a 30″ monitor with massive amounts of data on it you can see trends, anomalies, etc.

And that doesn’t even include the concept of visuals like graphs and images that can convey massive amounts of information very quickly to the human brain. Voice isn’t ever going to compete with that in terms of efficiency, and that’s not a limitation of technology. It’s just how the brain works.

Hybrids mapped to use cases

The obvious answer is that various human tasks are associated with ideal input and output methods.

Voice input is great if you’re driving.

Text input is great if you’re in a library.

Voice output is great if you’re giving your computer basic commands at home.

Visual output is ideal if you need to see lots of data at once, or if the content itself is visual.

Neural interfaces are basically hardware shortcuts to all of these, and it’s too early to even talk about them much.

Voice vs. text

One way I see voice and text that I’ve not heard anywhere else is to imagine them as different forms of the same thing, i.e., natural language. You’re using mostly natural language to convey ideas or desires.

Show me this. I’ll be right there. Tell him to pick me up. I can’t talk now, I’m in a meeting. Order me three of those.

These are all things that you could do vocally or via text. There are of course conventions that are used in text that aren’t used in vocal speech, but they largely overlap. Text, in other words, is a technological way of speaking naturally. You’re not sending computer commands; you’re emulating the same speech we had 100,000 years ago around the campfire.

Common reasons to use text vs. voice include lower social friction, the ability to do it without being as disruptive to others around you, etc. But again, they’re very similar, and in terms of human to computer interface I think we can see them as identical save for implementation details. In both cases the computer has to be good at interpreting natural human speech.

Goals

The key is being able to determine the ideal input and output options for any given human task, and to continue to re-evaluate those options as the technologies for each continue to evolve.

Summary

There are many ways for humans to send input to, and receive output from, computers.

These methods are not hierarchical, meaning voice is not always better than text, and audible is not always better than visual.

Voice and text are different forms of “natural language” that computers need to be able to parse and respond to correctly.

Human tasks will map to one or more ideal input/output methods, and those will evolve along with available technology.

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

February 4, 2017

The Clash of Extreme Left and Extreme Right Will Create a New Centrism

Right now we’re seeing the extreme right clash with the extreme left, and people in the middle are being forced to choose.

It’s getting ugly.

There’s basically no place for people who think the following:

Both sides are messed up and wrong

The left has gone too far with their fetishization of being offended

Too much of Trump’s right has embraced white nationalist ideas

Too much of Trump’s right has decided to discard evidence and truth and replace it with fantasy

Even worse, most mistake the few centrists who remain with one extreme or the other. You’re either a crazy liberal (as judged by Trump people), or a non-thinking Trump supporter (if you’re talking to crazy liberals).

And those forces, of being confronted by various raving masses, then forces even more centrists to one side or the other. Or to abstain completely because there’s no place for them.

But I hope this will soon change.

In reading a number of books by Charles Wheelan recently, I came upon a political philosophy that could be exactly what we will need once we finish with the current ideological war.

From Wikipedia:

The “radical” in the term refers to a willingness on the part of most radical centrists to call for fundamental reform of institutions. The “centrism” refers to a belief that genuine solutions require realism and pragmatism, not just idealism and emotion. Thus one radical centrist text defines radical centrism as “idealism without illusions”.

Most radical centrists borrow what they see as good ideas from left, right, and wherever else they may be found, often melding them together. Most support market-based solutions to social problems with strong governmental oversight in the public interest.

We’re about to see a nasty clash between extremes in this country, and it’s going to appear as if there’s no middle left.

But there is, and they’re tired of being forced to choose between different sets of emotional, short-sighted, and harmful ideas.

From the ashes we’ll assemble something new.

Something that refuses to be offended for fun

Something that stops seeing the past as something to worship

Something that embraces evidence and changes its mind when its shown wrong by data

Something that puts human humanist wellbeing above all else

Until we have something better, maybe we can point to Radical Centrism as some sort of beacon.

In the meantime, buckle in.

Notes

The image above is not mine, and if you know the creator I’d love to give them credit.

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

January 31, 2017

What is Mobile 2.0?

Today, ten years after the iPhone launched, I have some of the same sense of early constraints and assumptions being abandoned and new models emerging. If in 2004 we had ‘Web 2.0’, now there’s a lot of ‘Mobile 2.0’ around. If Web 2.0 said ‘lots of people have broadband and modern browsers now’, Mobile 2.0 says ‘there are a billion people with high-end smartphones now’*. So, what assumptions are being left behind?Source: Mobile 2.0

Benedict Evans makes some great points in this piece, and it got me thinking about how I would characterize both Web 2.0 and Mobile 2.0 if I were asked to do so.

I think I’d say the following:

Web 2.0: was the conversion from flat, link-based experiences to application-like experiences.

Mobile 2.0: will be the conversion from primarily using applications to using digital assistants via voice and text. In other words, it’ll be the transition from direct interaction to brokered interaction, with the brokers being your digital assistant and chat bots.

As I write about in The Real Internet of Things, this brokering is inevitable for several reasons. Here are two of them:

Computers (i.e., digital assistants) will be able to interact with the hundreds or thousands of daemons that surround us on our behalf, whereas humans will not be able to.

Voice and text (and eventually gesture, eye-tracking, and neural interfaces) are far more natural than poking at glass in different ways for different apps. The human will just express desires, and it’ll be up to the tech to sort it out, as opposed to the human explicitly poking buttons in the way demanded by the app.

Benedict does make a great point about a limitation of voice in replacing applications. If you have 20 applications on your mobile device, how are you supposed to remember them all? And how to use them all with pure voice / text.

I think the answer will come from a combination of high-quality digital assistants that make quality assumptions about what you want to do (and thus require you to be explicit less often), and advances in eye-tracking that can let you make selections from options more naturally than poking glass.

But to support his point, those will be a while. If we can’t remember what all Alexa can do for us, that same problem will follow us on mobile as we try to move to voice. Icons on glass will become reminders that you have the functionality as much as anything else.

Summary

Web 2.0 was the transition from links to web apps.

Mobile 2.0 is the transition from poking glass to naturally expressing desires to digital assistants and bots.

Because it’s hard to remember all the different capabilities of a strong digital assistant, there will still be a use case for displaying functionality—in whatever form—at least for the foreseeable future.

Notes

Even further out is the digital assistant using deep context to anticipate desires, curate choices, and otherwise remove the need for exhaustive choice selection.

I love his comment about visual sensors vs. cameras, which I also talk about in my book. The idea applies to all kinds of sensors, and all kinds of machine learning algorithms. The game is sensor to algorithm. Humans looking at a snapshot is going to be extremely old thinking soon.

If you’re not subscribed to Benedict’s newsletter, I recommend it strongly. It served as the inspiration for the reboot of my own newsletter, especially around the simple text-based design.

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

Exploring the Nature of Evil

Recent events have led me to contemplate the nature of evil—specifically as it pertains to government leaders.

I feel like there are two different types of ruler.

Those who believe they’re doing unpleasant but necessary things that will ultimately make things better and lead to them being loved by the people, and…

Those who don’t care what the people think and just want control and all the advantages that come with it.

I’m not an expert on either, but it seems like Quadafi just wanted to rule and didn’t care about the people’s opinion, whereas Hitler thought he was doing good for Germany and wanted its love and respect.

What I’m trying to untangle is whether the difference matters or not.

Let’s say you hated Obama’s presidency and you believe that even though he was trying to do the right thing he actually caused extreme harm to the country. This shouldn’t be hard to imagine, since millions of American’s clearly believe that.

And let’s say you hated George W. Bush’s presidency because you believe the Iraq war was unjustified, that it was based on a boy trying to impress his father and to become respected like Ronald Reagan.

In both cases, from each perspective, evil was done. Obama weakened our country, weakened our conservative values and our strength in the world, etc. And Bush lost us over 5 trillion dollars, killed hundreds of thousand of Iraqis and hundreds of Americans, and Iraq is now more of a mess than when Saddam was there.

So is Obama evil? Is George W. Bush evil?

I’d say no.

I’d say they’re misguided, or that they were at the time, and that their flawed understanding of the world caused them to make decisions that ultimately caused harm.

But then I think about Trump.

What does he want?

Is he someone who cares about America and who wants to be loved and respected for helping it succeed, like Bush and Obama and Hitler? Or is he someone who’s pretending those things simply for the purpose of gaining influence and wealth?

Does he really care, in other words, or would he happily cause pain and suffering to the entire country if he could become a supreme ruler with no risk of overthrow?

I think it’s the former. I think he deeply cares about the country and is actually trying to fix it.

But so was Jimmy Carter. And Reagan. And yes, Hitler.

I’m obviously not equating any of these people in any other way than intentions and motivations, but I’m starting to wonder if it matters at all.

Let’s assume that Carter and Obama were philosopher kings who were too good for the presidency. Let’s assume they tried too hard to be nice, and the result was harm to the country.

And let’s assume that Reagan and Bush and Hitler thought the answer was force and unpleasantness, but they truly believed that once it was all done they’d be left with a healthy, thriving country that remembered them as the leader who got them through.

Does it matter?

Does it matter what your intentions are? Or where your heart is? If Santa Claus, Sean Hannity, and Ted Bundy would all be bad world leaders, does it matter what would make them bad?

When I see Trump playing Celebrity Apprentice: White House, obsessing over his perceived popularity, insisting that people laugh at his jokes during official public addresses, making clumsy and dangerous policy decisions with no understanding or regard for implications, and attacking media who don’t report on him favorably, I am hit with multiple signals and thoughts.

He’s trying to do the right thing and he’s just inexperienced.

He’s a raving lunatic and we should start impeachment hearings immediately.

The liberals really did mess things up, and maybe when the dust settles we’ll see some actual positives out of all this.

The guy is 70 years old and everyone he cares about is a billionaire. He’s not in this for money.

It doesn’t matter what he’s doing it for; he’s fucking everything up.

Honestly I’m not sure where I’m going with this. I was hoping for some resolution or clarity.

In the past when I saw what I perceived to be evil acts I always asked the question:

What is the person trying to do? What’s their goal?

And now I’ve realized it isn’t actually a good benchmark.

Hitler might have wanted lots of art galleries and Christmas music during the holidays. I like those things too. And maybe he had a great sense of humor and could do really good animal impressions.

I don’t care.

Maybe he wanted a united and vibrant Germany where everyone loved each other and smiled when they passed each other on the street.

I don’t care. He slaughtered millions of people.

And maybe Bush wanted to be a hero, and earn his Dad and brother’s respect, by doing the thing that everyone said he couldn’t do. And maybe he thought Iraq would love him just like America.

I don’t care. He lead to the deaths of hundreds of thousands, destabilized an entire region, and created ISIS.

And maybe Obama thought being nice solves problems, and that closing Guantanamo was complicated, and that giving Iran most of what they wanted and letting Putin walk all over us was best in the long run.

I don’t care. The result is that we have an alt-right revolution in this country right now because he let hyper-liberals hijack all the narratives.

Maybe the only thing that matter are actions, and whether those actions lead to better or worse outcomes.

And maybe that’s completely relative, based on who’s making the judgements of good and bad.

So we’re lost.

You can’t judge by intentions because you can have the best of intentions and produce the worst of outcomes. And you can’t judge by desired outcomes because nobody can agree on what the goals should be.

So I have no solutions for Trump, or even any good ways to analyze the problem. He probably wants to do good things. He’s had good ideas. He is also disconnected from reality in a frightening way, has shown at the very least lenience towards extremely non-humanist ideologies, and he appears prone to very random behavior.

In many of my essays this is where I give some sort of solution, or at least a direction to look for one.

In this case I have neither.

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

January 30, 2017

Unsupervised Learning: No. 63

This week’s topics: Peak Prevention at AppSec Cali, Austrian Hotel Ransomware, Russian FSB Drama, WordPress Issues, AV Conflicts, Uber Pays Another Company’s Bounty, Data Science, Rules for Rulers…

This is Episode No. 63 of Unsupervised Learning—a weekly show where I curate 3-5 hours of reading in infosec, technology, and humans into a 15 to 30 minute summary.

The goal is to catch you up on current events, tell you about the best content from the week, and hopefully give you something to think about as well.

The show is released as a Podcast on iTunes, Overcast, Android, or RSS—and as a Newsletter which you can view and subscribe to here or read below.

Click the image to read the full newsletter.

Thank you for listening, and if you enjoy the show please share it with a friend or on social media.

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

January 29, 2017

We Have an Idiocracy Problem, Not an Orwell Problem

People are extremely fond of referencing Orwell right now, and specifically 1984. So much so in fact that it’s just become a #1 bestseller again.

I think the analysis is a bit off.

The key characteristic of Orwellian society is oppression. That means that the people are vibrant, full of life, and the government is a well-organized force that keeps them down. The key element there is that they actually control information. They determine what people hear and therefore what they believe.

That’s not what we have in America right now.

What we have is more like what Huxley warned about, which is a situation where the people no longer care what’s true. They simply go about their business, chase shiny things, amuse themselves with recreation, and let the government do whatever it wants.

We’re closer to that today than we are an Orwellian society, but there’s another model that’s even more applicable.

Idiocracy.

In Idiocracy, the people are so ignorant and gullible that they celebrate the wrong things. The respect bragging, power, bling, and all the other lower forms of signaling strength. And because they’re so ignorant they can’t tell the difference between what’s true and what’s not.

That’s what got us here—not an Orwellian level of control and deception.

We can see the differences in a few different ways:

First, the current administration is not that organized or coordinated. They’re more like a Magic 8-ball of mostly bad ideas.

Second, they don’t have control over what’s being heard. They’re just blasting their narratives at full volume and hoping it’ll confuse and convince some percentage of the masses—which they have.

Third, there isn’t a singular goal that they’re pursuing. It’s many different and opposing groups emotionally pushing their own individual agendas.

This isn’t Orwell, and it’s not even Huxley. Huxley’s dystopia, like Orwell’s, was maliciously designed to make people not care. It was engineered to distract the people and put them to sleep so that the real world order could reign.

Again, that requires a lot of organization, very long-game thinking, and meticulous planning and execution.

We don’t have any of that in this mess. What we have are Idiocratic opportunists shouting slogans and getting the ignorant masses riled up. They’re tapping into emotions, obscuring facts, and taking full advantage of their audience’s distaste of subtlety and evidence in discussion.

I’m never one to discourage people from reading Orwell, but it’s a bit of a waste to build a mental defense against an ailment that we’re not actually facing.

Quite simply, our problem isn’t the government; our problem is the people who brought it to power.

As someone recently pointed out at a protest,

Don’t blame Trump. He repeatedly demonstrated that he was unfit to lead the country, and we elected him anyway.

Pointing to the government as the problem, which is the message with both Orwell and Huxley, doesn’t help us much right now.

If we want to find our way out of this mess we need to find a way to address the millions of people who wanted him here and think he’s doing a good job. If you can’t fix that, you can’t fix anything else.

That’s an Idiocracy problem, not an Orwellian one.

Notes

And no, I’m not saying anyone who voted for Trump is an idiot or part of the Idiocracy. But as a rule I would say that he absolutely perpetrated a mass-deception that required significant ignorance in his followers. That doesn’t mean he didn’t make good points, or that people couldn’t have voted for him for good reasons. It simply wasn’t the majority of what happened.

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

A Simplified Definition of “Data Scientist”

There is a lot of controversy around the definition of a Data Scientist.

Some think it means being a statistician, others think it means being a technologist, and others have still other requirements.

I think the best definitions are more general and goal-based, and look something like these:

Data Scientist

/’dadə sīən(t)əst’/

noun

1. Someone who specializes in collecting, massaging, and/or displaying data in order to tell a story that results in a positive outcome.

2. Someone who can technically extract meaning from information in a way that enables decision makers to make better choices.

3. Someone who can extract business value from data using mathematics and technology.

Importantly, this could be a triple-Ph.D in statistics, maths, and computer science, or a talented graphic designer with some decent Python skills.

The key is that they’re able to use data to illuminate how the world works and facilitate progress.

So you can break down the definitions into 49.6 different categories and sub-categories, or you can use this approach and focus on outcomes.

I think this approach is more resilient, especially given how quickly the field is changing.

Notes

The definitions above assume both good faith and possession of requisite talent/skills. Manipulation and incompetence are not in scope.

There’s a humorous alternative definition which says, “A data scientist is someone who’s better at statistics than any software engineer, and better at software engineering than any statistician.”

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

January 27, 2017

Hitting Peak Prevention

These are my slides from AppSec Cali 2017, where I delivered a conceptual talk called Peak Prevention. It was a crap presentation/delivery, but the idea is pretty solid I think.

In retrospect, that’s not the conference for this type of talk. I knew that already, but when it comes time to submit I tend to just submit whatever’s on my mind at the time. I need to get better at matching content to conference, since I like to both technical stuff and idea stuff.

I’ve been thinking about this idea of Peak Prevention for many years, and the concept is quite simple:

Risks is made up of probability and impact, and we have hit a point of diminishing return with preventing bad things from happening. If we want to significantly reduce risk at this point we need to lower the other side of the equation (impact), which equates to resilience. In short, the future of risk reduction in an open society in many, many cases will come from resilience, not from prevention.

It really should have been a 15 minute talk, which has an associated essay. That’s the direction I’m started to head for these types of things. Crisp, concise concepts—delivered in a way that doesn’t waste anyone’s time. Instant value, instant takeaways.

Anyway, those are the slides. It’s not very textual so you’ll have to sort of imagine the flow, but I’ll do a standalone essay on the topic soon.

Notes

The conversion to PowerPoint borked my super sick fonts. Don’t hate on my typography; it got mangled.

---

I do a weekly show called Unsupervised Learning, where I collect the most interesting stories in infosec, technology, and humans, and talk about why they matter. You can subscribe here.

Daniel Miessler's Blog

- Daniel Miessler's profile

- 18 followers