Roland Kelts's Blog, page 27

February 19, 2016

CG finally a force in anime, for The Japan Times

Published on February 19, 2016 00:55

February 17, 2016

Naka-Kon 2016, Kansas City, March 11 - 15

Honored to be a featured guest at Naka-Kon 2016 in Kansas City, March 11-13.

Roland KeltsConvention Year: 2016

Roland Kelts is the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling book "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US." He was born to an American father and a Japanese mother and grew up in both countries. He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo and a steering committee member of the Rebuild Japan Initiative Foundation, a Tokyo-based think tank. As a journalist, essayist, and columnist, he writes for many publications, such as The New Yorker, Time magazine, Newsweek Japan, The New York Times, The Guardian and The Japan Times. An authority on Japan’s contemporary literary and popular cultures, Roland imparts his unique perspective on Japanese pop culture to the rest of the world as a public speaker and media commentator on CNN, NPR, NHK and the BBC. Recently, Kelts delivered a lecture at the World Economic Forum and a TED Talk in Tokyo. He also serves as a contributing editor for Monkey Business, Japan’s premier literary magazine. His forthcoming novel is called "Access."

Roland Kelts is the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling book "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US." He was born to an American father and a Japanese mother and grew up in both countries. He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo and a steering committee member of the Rebuild Japan Initiative Foundation, a Tokyo-based think tank. As a journalist, essayist, and columnist, he writes for many publications, such as The New Yorker, Time magazine, Newsweek Japan, The New York Times, The Guardian and The Japan Times. An authority on Japan’s contemporary literary and popular cultures, Roland imparts his unique perspective on Japanese pop culture to the rest of the world as a public speaker and media commentator on CNN, NPR, NHK and the BBC. Recently, Kelts delivered a lecture at the World Economic Forum and a TED Talk in Tokyo. He also serves as a contributing editor for Monkey Business, Japan’s premier literary magazine. His forthcoming novel is called "Access."

Roland KeltsConvention Year: 2016

Roland Kelts is the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling book "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US." He was born to an American father and a Japanese mother and grew up in both countries. He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo and a steering committee member of the Rebuild Japan Initiative Foundation, a Tokyo-based think tank. As a journalist, essayist, and columnist, he writes for many publications, such as The New Yorker, Time magazine, Newsweek Japan, The New York Times, The Guardian and The Japan Times. An authority on Japan’s contemporary literary and popular cultures, Roland imparts his unique perspective on Japanese pop culture to the rest of the world as a public speaker and media commentator on CNN, NPR, NHK and the BBC. Recently, Kelts delivered a lecture at the World Economic Forum and a TED Talk in Tokyo. He also serves as a contributing editor for Monkey Business, Japan’s premier literary magazine. His forthcoming novel is called "Access."

Roland Kelts is the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling book "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US." He was born to an American father and a Japanese mother and grew up in both countries. He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo and a steering committee member of the Rebuild Japan Initiative Foundation, a Tokyo-based think tank. As a journalist, essayist, and columnist, he writes for many publications, such as The New Yorker, Time magazine, Newsweek Japan, The New York Times, The Guardian and The Japan Times. An authority on Japan’s contemporary literary and popular cultures, Roland imparts his unique perspective on Japanese pop culture to the rest of the world as a public speaker and media commentator on CNN, NPR, NHK and the BBC. Recently, Kelts delivered a lecture at the World Economic Forum and a TED Talk in Tokyo. He also serves as a contributing editor for Monkey Business, Japan’s premier literary magazine. His forthcoming novel is called "Access."

Published on February 17, 2016 07:27

February 9, 2016

Tokyo International Literary Festival 2016, March 2 - 6

I will be appearing at two events in next month's Tokyo International Literary Festival, March 4 & 6. Copies of Monkey Business Issue 6 and

*MARCH 4:

会期 :

3月4日

時間 :

18:00~20:00

会場 :

上智大学 12号館502教室

住所 :

入場料 :

無料

予約 :

不要 ※定員75名

出演者 :

トレーシー・スレーター / ジェイク・エーデルスタイン / マーク・カウフマン / ローランド・ケルツ / 贄田 貴美

Four Storiesとは4人の作家の朗読を中心としたグローバル文芸イベント。書き手と読み手、そして関心のあるあらゆる人びとをつなぎ、物語に耳を傾け、対話を生み出すことが狙いです。(英語のみ)

主催: Four Stories/上智大学英語学科共同主催

お問い合せ先担当者: 贄田貴美、マーク・カウフマン / 8:00 - 16:00 [平日]

Four Stories is an award-winning global literary series, bringing together writers, readers, intellectuals, friends and interested people to talk, laugh, hear stories, and trade tales about literature. This event will be in English

「文芸フェスイベント Monkey Business(英語版) presents スティーヴ・エリクソン 自作を語る 」

現代アメリカ最重要作家が自作を語ります!!

*MARCH 6:会期 :3月6日時間 :15:00(開場: 14:30)会場 :HMV&BOOKS TOKYO 7F イベントスペース住所 :HMV&BOOKS TOKYO 〒150-0041 東京都渋谷区神南1-21-3 渋谷モディ5F・6F・7F入場料 :無料 ※イベント終了後にサイン会を予定しております。 HMV&BOOKS TOKYOにてイベント告知開始日より、対象商品お買い上げの方にサイン会参加券を差し上げます(参加券の枚数には限りがございます)予約 :不要出演者 :スティーヴ・エリクソン / ローランド・ケルツ / 柴田元幸2月27日発売『ゼロヴィル』(白水社)ほか、『黒い時計の旅』、『Xのアーチ』の著者スティーヴ・エリクソンが2015年11月にオープンしたHMV&BOOKS TOKYOに登場!! 現代アメリカ文学の最重要作家、エリクソンが自身の作品について語ります。翻訳家、柴田元幸さんによる司会と通訳!

主催: HMV&BOOKS TOKYO お問い合わせ先: 03-5784-3270(武藤・鏡味・松田) / 営業時間: 11:00~23:00

*MARCH 4:

会期 :

3月4日

時間 :

18:00~20:00

会場 :

上智大学 12号館502教室

住所 :

入場料 :

無料

予約 :

不要 ※定員75名

出演者 :

トレーシー・スレーター / ジェイク・エーデルスタイン / マーク・カウフマン / ローランド・ケルツ / 贄田 貴美

Four Storiesとは4人の作家の朗読を中心としたグローバル文芸イベント。書き手と読み手、そして関心のあるあらゆる人びとをつなぎ、物語に耳を傾け、対話を生み出すことが狙いです。(英語のみ)

主催: Four Stories/上智大学英語学科共同主催

お問い合せ先担当者: 贄田貴美、マーク・カウフマン / 8:00 - 16:00 [平日]

Four Stories is an award-winning global literary series, bringing together writers, readers, intellectuals, friends and interested people to talk, laugh, hear stories, and trade tales about literature. This event will be in English

「文芸フェスイベント Monkey Business(英語版) presents スティーヴ・エリクソン 自作を語る 」

現代アメリカ最重要作家が自作を語ります!!

*MARCH 6:会期 :3月6日時間 :15:00(開場: 14:30)会場 :HMV&BOOKS TOKYO 7F イベントスペース住所 :HMV&BOOKS TOKYO 〒150-0041 東京都渋谷区神南1-21-3 渋谷モディ5F・6F・7F入場料 :無料 ※イベント終了後にサイン会を予定しております。 HMV&BOOKS TOKYOにてイベント告知開始日より、対象商品お買い上げの方にサイン会参加券を差し上げます(参加券の枚数には限りがございます)予約 :不要出演者 :スティーヴ・エリクソン / ローランド・ケルツ / 柴田元幸2月27日発売『ゼロヴィル』(白水社)ほか、『黒い時計の旅』、『Xのアーチ』の著者スティーヴ・エリクソンが2015年11月にオープンしたHMV&BOOKS TOKYOに登場!! 現代アメリカ文学の最重要作家、エリクソンが自身の作品について語ります。翻訳家、柴田元幸さんによる司会と通訳!

主催: HMV&BOOKS TOKYO お問い合わせ先: 03-5784-3270(武藤・鏡味・松田) / 営業時間: 11:00~23:00

Published on February 09, 2016 21:50

February 4, 2016

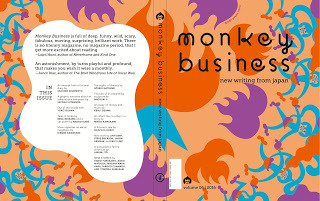

Monkey Business # 6

Published on February 04, 2016 04:03

January 17, 2016

On this year's anime revolutions in Japan & US, for The Japan Times

Online streaming keeps anime afloat

By ROLAND KELTS

Last week in California, I caught up with some of the chief purveyors of Japanese popular culture in the United States and elsewhere in the world. It became rapidly clear that 2016 won’t be at all like 2015 — or any other year before it.

The rollout of streaming media is fast approaching an avalanche. Mainstream portals Hulu and Netflix are snapping up anime licenses in an effort to target an expanding niche of young and dedicated global fans. Crunchyroll, the pioneer and leader in the market, is exploring content coproduction deals with anime studios, as Japan’s notoriously byzantine anime production committees slowly disintegrate in the face of plunging domestic DVD sales.

Anaheim, California-based Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation (SPJA), the nonprofit organization behind Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention, is expanding, refocusing and rebranding. It plans to move beyond otaku/fan culture and embrace the broader challenge of integrating successful conventions in film, gaming, tech, music and other forms of entertainment media. SPJA will open an office in Tokyo later this year and will soon reveal a new brand name and logo.

Anime Expo hosts its 25th event in July. The con has signed as its first featured guest Japanese artist and character designer Yoshitaka Amano, whose works include decades-spanning iconic titles — from “Speed Racer” and “Gatchaman” to “Vampire Hunter D” and “Final Fantasy.”

Azusa Matsuda, the SPJA’s director of industry relations, tells me that the anniversary will be a chance to take stock of anime history. “It would be great if we could stage some events looking back on 25 years of Anime Expo, and at those same years in terms of anime and manga. How did we get here? More than half of our attendees are 18-25 years old. They love anime, but they want to know more, they want context.”

Originally from Arima Onsen, Kobe, Matsuda has lived in California for 28 years, nine of which she spent localizing Japanese entertainment content. Before joining SPJA, she was a translator for a gaming import company and a localization developer for Burbank, California-based post-production, audio and creative studio, Bang Zoom! Entertainment.

Azusa Matsuda

Azusa Matsuda

The biggest changes she sees in 2016 are interrelated: The transition from physical products, or “package businesses,” to on-demand, streaming media has resulted in a radical transformation in the intellectual-property licensing process.

“There was ‘before Netflix,’ and an ‘after Netflix,’ ” she says. “And it happened in only the past three or four years. Before, you sold your content to (U.S.-based distributors) like Viz Media or Funimation, Aniplex and Media Blasters. But with Netflix, you can sell it to them directly and go straight to your audience. You don’t have to have this industry connection and talk to these U.S.-based licensing companies. You can just go to Netflix and sell it and that’s it.”

The success of the new model relies on the diehard and insatiable devotion of niche fanatics, what Crunchyroll CEO Kun Gao recently called “passion audiences.” Anime fans were binge viewers long before U.S. TV serials like “Breaking Bad” and “The Walking Dead” were scripted, and the now seven-year-old Crunchyroll targeted, cultivated and respected them — to the tune of 20 million users, 750,000 paid subscribers and the backing of Hollywood and telecommunications company AT&T.

"Knights of Sidonia"(c)TSUTOMU NIHEI・KODANSHA/KOS PRODUCTION COMMITTEE

"Knights of Sidonia"(c)TSUTOMU NIHEI・KODANSHA/KOS PRODUCTION COMMITTEE

For most Japanese producers, Matsuda says, the watershed moment occurred in 2013, when the Tokyo-based 3-D computer graphics studio Polygon Pictures clinched a deal with Netflix for the distribution of its series “Knights of Sidonia.”

“Everyone (in the anime industry) was like, ‘Oh, crap: Can you do that directly with streaming? And then, ‘Oh, wow, you really can!’ “

Shuzo Shiota, Polygon’s president, tells me that his studio’s specialization in digital media is an asset when competing in Japan’s relatively conservative and parochial anime industry.

“Digital animation studios like us have had difficulty gaining a footing in the Japanese market,” he says. “So, we’ve worked with North American clients, including Disney and Hasbro, for the past decade, building trust and reputation. Not being tied down to legacy industry norms in Japan allowed us to react swiftly to the massive changes happening in media and content distribution.”

In 2016, Japanese IP producers are scrambling to sell their content directly to fans, while conjuring new ways to pay for it. On a recent flight from New York to Manila via Tokyo, I watched an entire season of “Knights of Sidonia,” offered on the same sub-menu that included mainstream U.S. films and series such as “The Martian” and “Game of Thrones.”

Matsuda is sanguine about the shakeup of the domestic Japanese industry. “I hope this pushes anime creators to make more content that doesn’t have to follow the norm in Japan,” she says. “With options like Kickstarter and digital streaming, there are now a lot more ways to get your IP out there, wherever you are.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

By ROLAND KELTS

Last week in California, I caught up with some of the chief purveyors of Japanese popular culture in the United States and elsewhere in the world. It became rapidly clear that 2016 won’t be at all like 2015 — or any other year before it.

The rollout of streaming media is fast approaching an avalanche. Mainstream portals Hulu and Netflix are snapping up anime licenses in an effort to target an expanding niche of young and dedicated global fans. Crunchyroll, the pioneer and leader in the market, is exploring content coproduction deals with anime studios, as Japan’s notoriously byzantine anime production committees slowly disintegrate in the face of plunging domestic DVD sales.

Anaheim, California-based Society for the Promotion of Japanese Animation (SPJA), the nonprofit organization behind Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention, is expanding, refocusing and rebranding. It plans to move beyond otaku/fan culture and embrace the broader challenge of integrating successful conventions in film, gaming, tech, music and other forms of entertainment media. SPJA will open an office in Tokyo later this year and will soon reveal a new brand name and logo.

Anime Expo hosts its 25th event in July. The con has signed as its first featured guest Japanese artist and character designer Yoshitaka Amano, whose works include decades-spanning iconic titles — from “Speed Racer” and “Gatchaman” to “Vampire Hunter D” and “Final Fantasy.”

Azusa Matsuda, the SPJA’s director of industry relations, tells me that the anniversary will be a chance to take stock of anime history. “It would be great if we could stage some events looking back on 25 years of Anime Expo, and at those same years in terms of anime and manga. How did we get here? More than half of our attendees are 18-25 years old. They love anime, but they want to know more, they want context.”

Originally from Arima Onsen, Kobe, Matsuda has lived in California for 28 years, nine of which she spent localizing Japanese entertainment content. Before joining SPJA, she was a translator for a gaming import company and a localization developer for Burbank, California-based post-production, audio and creative studio, Bang Zoom! Entertainment.

Azusa Matsuda

Azusa MatsudaThe biggest changes she sees in 2016 are interrelated: The transition from physical products, or “package businesses,” to on-demand, streaming media has resulted in a radical transformation in the intellectual-property licensing process.

“There was ‘before Netflix,’ and an ‘after Netflix,’ ” she says. “And it happened in only the past three or four years. Before, you sold your content to (U.S.-based distributors) like Viz Media or Funimation, Aniplex and Media Blasters. But with Netflix, you can sell it to them directly and go straight to your audience. You don’t have to have this industry connection and talk to these U.S.-based licensing companies. You can just go to Netflix and sell it and that’s it.”

The success of the new model relies on the diehard and insatiable devotion of niche fanatics, what Crunchyroll CEO Kun Gao recently called “passion audiences.” Anime fans were binge viewers long before U.S. TV serials like “Breaking Bad” and “The Walking Dead” were scripted, and the now seven-year-old Crunchyroll targeted, cultivated and respected them — to the tune of 20 million users, 750,000 paid subscribers and the backing of Hollywood and telecommunications company AT&T.

"Knights of Sidonia"(c)TSUTOMU NIHEI・KODANSHA/KOS PRODUCTION COMMITTEE

"Knights of Sidonia"(c)TSUTOMU NIHEI・KODANSHA/KOS PRODUCTION COMMITTEEFor most Japanese producers, Matsuda says, the watershed moment occurred in 2013, when the Tokyo-based 3-D computer graphics studio Polygon Pictures clinched a deal with Netflix for the distribution of its series “Knights of Sidonia.”

“Everyone (in the anime industry) was like, ‘Oh, crap: Can you do that directly with streaming? And then, ‘Oh, wow, you really can!’ “

Shuzo Shiota, Polygon’s president, tells me that his studio’s specialization in digital media is an asset when competing in Japan’s relatively conservative and parochial anime industry.

“Digital animation studios like us have had difficulty gaining a footing in the Japanese market,” he says. “So, we’ve worked with North American clients, including Disney and Hasbro, for the past decade, building trust and reputation. Not being tied down to legacy industry norms in Japan allowed us to react swiftly to the massive changes happening in media and content distribution.”

In 2016, Japanese IP producers are scrambling to sell their content directly to fans, while conjuring new ways to pay for it. On a recent flight from New York to Manila via Tokyo, I watched an entire season of “Knights of Sidonia,” offered on the same sub-menu that included mainstream U.S. films and series such as “The Martian” and “Game of Thrones.”

Matsuda is sanguine about the shakeup of the domestic Japanese industry. “I hope this pushes anime creators to make more content that doesn’t have to follow the norm in Japan,” she says. “With options like Kickstarter and digital streaming, there are now a lot more ways to get your IP out there, wherever you are.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Published on January 17, 2016 08:53

January 15, 2016

On 2016 anime revolutions in Japan & the US, for The Japan Times

Published on January 15, 2016 17:29

January 8, 2016

On Japan's troubled farmlands, for The Australian Financial Review

Beyond Japan's glittering cities lies a troubled farm sector

By Roland Kelts

I recently visited Aizuwakamatsu, a rural rice-farming region in northern Japan. The scenery was storybook Asia: precipitous hills, dense with greenery, dipping into narrow-cut rice paddies hedged by brooks and streams. At the onset of dusk one evening, our minivan rounded a hillside overlooking the Tadami River. A cluster of homes emerged through the mist, pastel green, pink and pale blue roofs huddled on a patch of land jutting from the shore. With the mountains mirrored in the water surrounding it, the village looked as though it were floating.

One of the local guides told me that the coloured roofs were made of tin or aluminium, covering or entirely replacing the original thatchwork, an icon of traditional Japanese architecture. Upkeep had become too expensive, and the risk of fires or snow collapses too much for elderly inhabitants to bear. But what is really sad, she said, is that no one wants to live here any more. Rural Japan is dying.

Japan boasts the highest female life expectancy (86.8 years) and the world's greatest number of centenarians per capita (the country is home to 61,568 people aged 100 or older): signs of achievements in health care, diet and societal stability. But it is no net positive. The perfect storm of declining rates of marriage and birth – in 2014 only 1.001 million babies were born, the lowest number since data was first collected in 1899 – is such that Japan's population is not just ageing faster than anywhere else, it is also disappearing.

One consequence is that the country has an estimated three million deserted homes, according to The Japan Times. The Nomura Research Institute projects that a fifth of all Japanese homes will be abandoned by 2023. Nationwide, residential land prices have plummeted for seven years straight.

The impact of Japan's greying population has been most evident outside its main cities, where the young can't find sustainable jobs, whether or not they want them, and so decamp in droves for urban centres.

The opposite is happening in Tokyo, where the population of the metropolitan area has increased for 19 consecutive years, growing by roughly 100,000 in 2014 to 38 million. New high-rise hotels and condos puncture the skyline ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, drawing moneyed young professionals and retirees, as well as free-spending tourists, mostly from China.

But beyond the capital's glow lies a wasteland of abandoned houses, schools, resorts and theme parks. "The prime reason [abandoned buildings] are legion is because they are in the wrong place," says Richard Hendy, whose blog Spike Japan documents the decline of the emptying villages and towns. "Emigration to the big cities is the biggest culprit," he tells me about Japan's hollowing out. "Absolute household numbers are not expected to peak for about a decade, as more and more people live alone or in one-or two-generation nuclear families with one or no children."

Hendy adds: "You won't find abandoned houses in my corner of [Tokyo]."

Cultural sensibilities may also be at play. Japan has long embraced the new over the old. The archetypal Japanese home consists of what westerners would consider transitory materials – wood, paper, straw – not built to last, partly because Japan is buffeted by natural disasters: earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes and typhoons.

Every two decades the Grand Shrine at Ise, among Japan's most sacred, gets demolished and reconfigured. This summer, the destruction of Tokyo's beloved modernist Hotel Okura, featured in the Bond novel You Only Live Twice, drew howls of futile protest. A new high-rise with 21st-century amenities will take its place.

Many of the structures now abandoned to rot and ruin – "ghost homes", in the phrase coined by The New York Times' Tokyo correspondent Jonathan Soble, in an article this summer – were hastily erected during the postwar years as Japan's economic juggernaut took flight. A 30-year lifespan was the standard target. It would make more sense, both technologically and economically, to destroy and build anew, meeting the safety specs of the future and keeping the real-estate market humming.

The postwar imperative to build created a property tax that is today completely at odds with Japan's real-estate crisis: the government will punish you if you demolish a house without building a new one, raising taxes on your empty land up to six times if you leave it that way.

There are marginal efforts under way to turn the emptied houses into living homes. In Kyoto, the "Machiya [traditional wooden merchant townhouses] Machizukuri Fund" has drawn increasing numbers of overseas investors, attracted by the weak yen and the chance to revive the dying art of a Unesco-blessed aesthetic.

Closer to Tokyo, I met Yoshihiro Takishita, a 72-year-old architect, this summer at his restored farmhouse in the seaside city of Kamakura. He has created a career out of dismantling, moving, restoring and modernising the materials and techniques of Japan's rural builders. To date, he has completed over 30 projects, spanning four countries.

For Takishita, who discovered his love of traditional Japan with his adoptive father, the late American AP journalist John Roderick, the art of keeping old homes alive is more spiritual than practical. "My kind of a traditional Japanese farmhouse is like a Shinto shrine, a shrine to nature," he says, as we survey the sea from his pitch-roofed balcony. "Young Japanese only want the cheap and the new. But there is a mystery to the spaces inside these homes that has a healing power. It's very comforting."

Roland Kelts is the author of "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the US," published by Palgrave Macmillan.

By Roland Kelts

I recently visited Aizuwakamatsu, a rural rice-farming region in northern Japan. The scenery was storybook Asia: precipitous hills, dense with greenery, dipping into narrow-cut rice paddies hedged by brooks and streams. At the onset of dusk one evening, our minivan rounded a hillside overlooking the Tadami River. A cluster of homes emerged through the mist, pastel green, pink and pale blue roofs huddled on a patch of land jutting from the shore. With the mountains mirrored in the water surrounding it, the village looked as though it were floating.

One of the local guides told me that the coloured roofs were made of tin or aluminium, covering or entirely replacing the original thatchwork, an icon of traditional Japanese architecture. Upkeep had become too expensive, and the risk of fires or snow collapses too much for elderly inhabitants to bear. But what is really sad, she said, is that no one wants to live here any more. Rural Japan is dying.

Japan boasts the highest female life expectancy (86.8 years) and the world's greatest number of centenarians per capita (the country is home to 61,568 people aged 100 or older): signs of achievements in health care, diet and societal stability. But it is no net positive. The perfect storm of declining rates of marriage and birth – in 2014 only 1.001 million babies were born, the lowest number since data was first collected in 1899 – is such that Japan's population is not just ageing faster than anywhere else, it is also disappearing.

One consequence is that the country has an estimated three million deserted homes, according to The Japan Times. The Nomura Research Institute projects that a fifth of all Japanese homes will be abandoned by 2023. Nationwide, residential land prices have plummeted for seven years straight.

The impact of Japan's greying population has been most evident outside its main cities, where the young can't find sustainable jobs, whether or not they want them, and so decamp in droves for urban centres.

The opposite is happening in Tokyo, where the population of the metropolitan area has increased for 19 consecutive years, growing by roughly 100,000 in 2014 to 38 million. New high-rise hotels and condos puncture the skyline ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, drawing moneyed young professionals and retirees, as well as free-spending tourists, mostly from China.

But beyond the capital's glow lies a wasteland of abandoned houses, schools, resorts and theme parks. "The prime reason [abandoned buildings] are legion is because they are in the wrong place," says Richard Hendy, whose blog Spike Japan documents the decline of the emptying villages and towns. "Emigration to the big cities is the biggest culprit," he tells me about Japan's hollowing out. "Absolute household numbers are not expected to peak for about a decade, as more and more people live alone or in one-or two-generation nuclear families with one or no children."

Hendy adds: "You won't find abandoned houses in my corner of [Tokyo]."

Cultural sensibilities may also be at play. Japan has long embraced the new over the old. The archetypal Japanese home consists of what westerners would consider transitory materials – wood, paper, straw – not built to last, partly because Japan is buffeted by natural disasters: earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes and typhoons.

Every two decades the Grand Shrine at Ise, among Japan's most sacred, gets demolished and reconfigured. This summer, the destruction of Tokyo's beloved modernist Hotel Okura, featured in the Bond novel You Only Live Twice, drew howls of futile protest. A new high-rise with 21st-century amenities will take its place.

Many of the structures now abandoned to rot and ruin – "ghost homes", in the phrase coined by The New York Times' Tokyo correspondent Jonathan Soble, in an article this summer – were hastily erected during the postwar years as Japan's economic juggernaut took flight. A 30-year lifespan was the standard target. It would make more sense, both technologically and economically, to destroy and build anew, meeting the safety specs of the future and keeping the real-estate market humming.

The postwar imperative to build created a property tax that is today completely at odds with Japan's real-estate crisis: the government will punish you if you demolish a house without building a new one, raising taxes on your empty land up to six times if you leave it that way.

There are marginal efforts under way to turn the emptied houses into living homes. In Kyoto, the "Machiya [traditional wooden merchant townhouses] Machizukuri Fund" has drawn increasing numbers of overseas investors, attracted by the weak yen and the chance to revive the dying art of a Unesco-blessed aesthetic.

Closer to Tokyo, I met Yoshihiro Takishita, a 72-year-old architect, this summer at his restored farmhouse in the seaside city of Kamakura. He has created a career out of dismantling, moving, restoring and modernising the materials and techniques of Japan's rural builders. To date, he has completed over 30 projects, spanning four countries.

For Takishita, who discovered his love of traditional Japan with his adoptive father, the late American AP journalist John Roderick, the art of keeping old homes alive is more spiritual than practical. "My kind of a traditional Japanese farmhouse is like a Shinto shrine, a shrine to nature," he says, as we survey the sea from his pitch-roofed balcony. "Young Japanese only want the cheap and the new. But there is a mystery to the spaces inside these homes that has a healing power. It's very comforting."

Roland Kelts is the author of "Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the US," published by Palgrave Macmillan.

Published on January 08, 2016 01:40

January 6, 2016

On Tokyo's new Hotel Okura, for The New York Times

In a Renewed Hotel Okura, Japanese Historians Still See a Loss

By ROLAND KELTS

The old main wing of Hotel Okura in Tokyo, now demolished. The new main wing is scheduled to open in 2019.

TOKYO — The outcry over the demolition last year of the 53-year-old Hotel Okura in Tokyo surprised no one more than Japanese historians and architectural specialists.

Monocle, the global lifestyle magazine, had circulated a petition, savetheokura.com, to register the “outrage from admirers of its unique design.” Tomas Maier, the creative director of Bottega Veneta, an Italian luxury brand, filmed a video memorial and started a social media campaign, #MyMomentAtOkura.

The hotel’s modernist postwar lobby artfully balanced elements of traditional Japan, like lacquered plum-blossom-shaped tables and chairs, with visions of what was then futuristic: a lighted world map displaying global time zones. It was frequented by United States presidents including President Obama, and other heads of state, celebrities, artists and designers. It played a central role in the 1960s James Bond novel “You Only Live Twice.”

Hotel Okura Co. Ltd., whose largest investors include the Taisei Corporation, a construction company, and Mitsubishi Estate, Japan’s second-largest real estate developer, plans to build a 38-story high-rise with 510 rooms, 102 more than the Okura, and add 18 stories of office space. The renovation is estimated to cost $1 billion. The company promised to “faithfully reproduce” several beloved artifacts in the lobby, including wall tapestries, paper lanterns and sliding doors, the lacquered furnishings and map of time zones.

The hotel’s main building and its signature lobby were demolished in September. The South Wing, erected in 1973, will remain operational, and the owners plan to replicate the lobby’s mezzanine, based on a Japanese painting known as “Bridge of the Dream,” and its hexagonal ceiling lights. A newly designed bar will try to recapture the stylish retro-chic of the former Orchid Bar, the Okura’s elegant, dimly lit cocktail haven loved by diplomats, expatriates and journalists. The new complex will also incorporate upgrades to meet the latest standards in earthquake-resistant construction technologies.

But those plans have done little to assuage the concerns of preservationists, many of whom contend that Tokyo is destroying its greatest postwar architectural assets to accommodate the 2020 Olympics and a recent surge in tourism. In a twist worthy of Bond, the most outspoken critics are not from Japan.

“When the reconstruction was announced, many foreigners, especially well-known designers, voiced their regret,” said Yoshio Uchida, professor of architecture at Toyo University. “The magnitude of their protest was beyond our imagination.”

The original Okura opened in 1962, two years before the first Tokyo Olympics, an event that signaled to the world that Japan had recovered from the devastation of World War II. It was erected across the street from the American Embassy, and became so popular with diplomats it was referred to as “the annex."

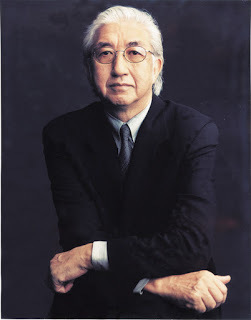

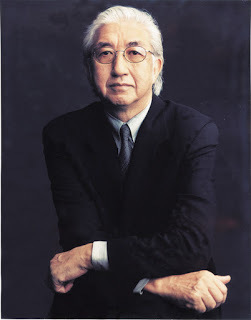

(Yoshio Taniguchi, architect. Credit Timothy Greenfield-Sanders)

(Yoshio Taniguchi, architect. Credit Timothy Greenfield-Sanders)

Unlike many postwar Tokyo buildings, whose primary models of modernism were strictly Western, the Okura was built to evoke Japanese-ness, at least as perceived by foreigners. Among other frills, this meant hanging lamps shaped like ancient gems and partitions edged with kimono fabrics.

But some Japanese question whether the Okura’s décor and ambience was, or could ever be, truly Japanese.

“In 1962, the very concept of a hotel was not Japanese,” Mr. Uchida said. “People wear shoes inside, they wear shirts and neckties. The traditional Japanese concept of lodging is the ryokan, or inn, where no one dresses or behaves that way.”

Yoshio Uchida

Yoshio Uchida

Recreating the Okura is the original architect’s world-famous son, Yoshio Taniguchi, a graduate of Harvard who 11 years ago redesigned the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Mr. Taniguchi is best known for his lean lines and conservative minimalism — a far cry, some say, from his father’s evocative focus on physical craftsmanship and genius for striking a harmonic balance between East and West.

Mr. Taniguchi is keenly aware of the affection bestowed upon his father’s Okura. He says he can incorporate the spirit and feel of the original in the new building, whatever its specifications.

“There were many examples of excellent modern architecture designed in postwar Japan,” he said. “But there are also many that have become rundown over the years. For the structures that were especially beautiful and original, we are trying to restore them with sensitivity to their original forms. We’re constantly making that effort.”

The pressure to revive and reinvent Tokyo is not limited to the Okura’s next incarnation. Real estate prices in the city plummeted in the 1990s. Modest upturns in the last decade were clouded by competition from shinier neighbors like Singapore, Seoul and Shanghai.

But while Japan’s population of about 126 million continues to decline with falling birthrates and an aging population, Tokyo’s population is growing annually. Last year, an estimated 100,000 joined the capital’s hordes of 38 million.

New York enclaves like SoHo and TriBeCa are losing local venues to high-rise condos, and many fear the same is happening in Tokyo. Mr. Uchida contends that the fate of the Hotel Okura is emblematic of a trend afflicting Japan’s capital.

“It’s a symbol of our struggle to balance our need for renewal with the treasures of our city,” he said. “That means it’s very important what happens.”

Hiroshi Matsukuma, a professor at the Kyoto Institute of Technology and a champion of postwar modernism, sees the virtues of Tokyo architecture in its layers of history. Tokyo’s major edifices of the 20th century, like the 11-story Okura, were modest by comparison with other global cities. But they embodied the organic, rapid growth of the city’s reconstruction, like rings in a tree trunk.

Projects undertaken since 2000, like the reconstructed Marunouchi Buildings, tend to be massive, multipurpose skyscrapers. “The multi-layeredness of Tokyo is something we may be losing now in our city’s major centers,” Mr. Matsukuma wrote. “You can only find it in the back streets, the old neighborhoods, and they are disappearing, too.”

Another challenge for Tokyo is more prosaic: The city has a shortage of hotel rooms. The Japan National Tourism Organization announced late last year that the number of foreign visitors to Japan was expected to near a record-breaking 20 million by the end of 2015, an increase of over 40 percent.

Occupancy rates for hotels in Tokyo are regularly at 90 percent or higher, and domestic businesses have begun complaining that their traveling salarymen can no longer find affordable rooms. The number of Asian tourists to Japan has exploded in the last year. China alone accounted for 4.7 million visitors, a 109 percent spike in one year.

The small number of additional rooms planned for the reconstructed Okura will do little to mitigate a trend that is forcing Tokyo to embrace another 21st-century development. Airbnb announced in November that Japan was by far its fastest-growing market.

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

By ROLAND KELTS

The old main wing of Hotel Okura in Tokyo, now demolished. The new main wing is scheduled to open in 2019.

TOKYO — The outcry over the demolition last year of the 53-year-old Hotel Okura in Tokyo surprised no one more than Japanese historians and architectural specialists.

Monocle, the global lifestyle magazine, had circulated a petition, savetheokura.com, to register the “outrage from admirers of its unique design.” Tomas Maier, the creative director of Bottega Veneta, an Italian luxury brand, filmed a video memorial and started a social media campaign, #MyMomentAtOkura.

The hotel’s modernist postwar lobby artfully balanced elements of traditional Japan, like lacquered plum-blossom-shaped tables and chairs, with visions of what was then futuristic: a lighted world map displaying global time zones. It was frequented by United States presidents including President Obama, and other heads of state, celebrities, artists and designers. It played a central role in the 1960s James Bond novel “You Only Live Twice.”

Hotel Okura Co. Ltd., whose largest investors include the Taisei Corporation, a construction company, and Mitsubishi Estate, Japan’s second-largest real estate developer, plans to build a 38-story high-rise with 510 rooms, 102 more than the Okura, and add 18 stories of office space. The renovation is estimated to cost $1 billion. The company promised to “faithfully reproduce” several beloved artifacts in the lobby, including wall tapestries, paper lanterns and sliding doors, the lacquered furnishings and map of time zones.

The hotel’s main building and its signature lobby were demolished in September. The South Wing, erected in 1973, will remain operational, and the owners plan to replicate the lobby’s mezzanine, based on a Japanese painting known as “Bridge of the Dream,” and its hexagonal ceiling lights. A newly designed bar will try to recapture the stylish retro-chic of the former Orchid Bar, the Okura’s elegant, dimly lit cocktail haven loved by diplomats, expatriates and journalists. The new complex will also incorporate upgrades to meet the latest standards in earthquake-resistant construction technologies.

But those plans have done little to assuage the concerns of preservationists, many of whom contend that Tokyo is destroying its greatest postwar architectural assets to accommodate the 2020 Olympics and a recent surge in tourism. In a twist worthy of Bond, the most outspoken critics are not from Japan.

“When the reconstruction was announced, many foreigners, especially well-known designers, voiced their regret,” said Yoshio Uchida, professor of architecture at Toyo University. “The magnitude of their protest was beyond our imagination.”

The original Okura opened in 1962, two years before the first Tokyo Olympics, an event that signaled to the world that Japan had recovered from the devastation of World War II. It was erected across the street from the American Embassy, and became so popular with diplomats it was referred to as “the annex."

(Yoshio Taniguchi, architect. Credit Timothy Greenfield-Sanders)

(Yoshio Taniguchi, architect. Credit Timothy Greenfield-Sanders)Unlike many postwar Tokyo buildings, whose primary models of modernism were strictly Western, the Okura was built to evoke Japanese-ness, at least as perceived by foreigners. Among other frills, this meant hanging lamps shaped like ancient gems and partitions edged with kimono fabrics.

But some Japanese question whether the Okura’s décor and ambience was, or could ever be, truly Japanese.

“In 1962, the very concept of a hotel was not Japanese,” Mr. Uchida said. “People wear shoes inside, they wear shirts and neckties. The traditional Japanese concept of lodging is the ryokan, or inn, where no one dresses or behaves that way.”

Yoshio Uchida

Yoshio UchidaRecreating the Okura is the original architect’s world-famous son, Yoshio Taniguchi, a graduate of Harvard who 11 years ago redesigned the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Mr. Taniguchi is best known for his lean lines and conservative minimalism — a far cry, some say, from his father’s evocative focus on physical craftsmanship and genius for striking a harmonic balance between East and West.

Mr. Taniguchi is keenly aware of the affection bestowed upon his father’s Okura. He says he can incorporate the spirit and feel of the original in the new building, whatever its specifications.

“There were many examples of excellent modern architecture designed in postwar Japan,” he said. “But there are also many that have become rundown over the years. For the structures that were especially beautiful and original, we are trying to restore them with sensitivity to their original forms. We’re constantly making that effort.”

The pressure to revive and reinvent Tokyo is not limited to the Okura’s next incarnation. Real estate prices in the city plummeted in the 1990s. Modest upturns in the last decade were clouded by competition from shinier neighbors like Singapore, Seoul and Shanghai.

But while Japan’s population of about 126 million continues to decline with falling birthrates and an aging population, Tokyo’s population is growing annually. Last year, an estimated 100,000 joined the capital’s hordes of 38 million.

New York enclaves like SoHo and TriBeCa are losing local venues to high-rise condos, and many fear the same is happening in Tokyo. Mr. Uchida contends that the fate of the Hotel Okura is emblematic of a trend afflicting Japan’s capital.

“It’s a symbol of our struggle to balance our need for renewal with the treasures of our city,” he said. “That means it’s very important what happens.”

Hiroshi Matsukuma, a professor at the Kyoto Institute of Technology and a champion of postwar modernism, sees the virtues of Tokyo architecture in its layers of history. Tokyo’s major edifices of the 20th century, like the 11-story Okura, were modest by comparison with other global cities. But they embodied the organic, rapid growth of the city’s reconstruction, like rings in a tree trunk.

Projects undertaken since 2000, like the reconstructed Marunouchi Buildings, tend to be massive, multipurpose skyscrapers. “The multi-layeredness of Tokyo is something we may be losing now in our city’s major centers,” Mr. Matsukuma wrote. “You can only find it in the back streets, the old neighborhoods, and they are disappearing, too.”

Another challenge for Tokyo is more prosaic: The city has a shortage of hotel rooms. The Japan National Tourism Organization announced late last year that the number of foreign visitors to Japan was expected to near a record-breaking 20 million by the end of 2015, an increase of over 40 percent.

Occupancy rates for hotels in Tokyo are regularly at 90 percent or higher, and domestic businesses have begun complaining that their traveling salarymen can no longer find affordable rooms. The number of Asian tourists to Japan has exploded in the last year. China alone accounted for 4.7 million visitors, a 109 percent spike in one year.

The small number of additional rooms planned for the reconstructed Okura will do little to mitigate a trend that is forcing Tokyo to embrace another 21st-century development. Airbnb announced in November that Japan was by far its fastest-growing market.

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Published on January 06, 2016 22:57

January 4, 2016

Happy New Year 2016 from Japan

Published on January 04, 2016 05:04

December 17, 2015

Hatsune Miku to tour North America in 2016, for The Japan Times

Published on December 17, 2015 22:48