Roland Kelts's Blog, page 29

October 28, 2015

On to Singapore for The Singapore Writers Festival & NUS

Roland KeltsUS/Japan

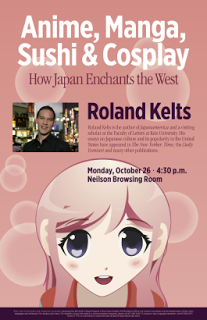

Roland Kelts is the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling Japanamerica. His articles, essays and fiction are published in The New Yorker, Time, the Wall Street Journal, The Village Voice, Newsweek Japan, Vogue, Cosmopolitan and The Japan Times, among others. He is also a frequent contributor to CNN, the BBC, NPR and NHK. He is a visiting scholar at Keio University and contributing editor of Monkey Business, Japan’s premier literary magazine. His forthcoming novel is called Access.

Roland Kelts is featured in the following SWF event(s):

THE JAPANESENESS OF THINGS31 Oct, Sat 4:00 PM - 5:00 PMTAH, Kumon Blue RoomFESTIVAL PASS EVENT

UNRAVELLING HARUKI MURAKAMI1 Nov, Sun 2:30 PM - 3:30 PMTAH, ChamberFESTIVAL PASS EVENT

NEW JAPAN RISING: VOICES FROM THE EDGE1 Nov, Sun 7:00 PM - 8:30 PMTAH, Kumon Blue RoomFESTIVAL PASS EVENT

Published on October 28, 2015 09:08

Arigato, Smith College

Published on October 28, 2015 09:05

October 27, 2015

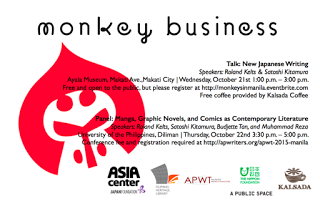

Monkey & Murakami in Manila, in the Philippines Inquirer

Want to satisfy your Murakami and manga cravings?

Check out Monkey Business

Japan Foundation, Manila hosts a forum on the new literary journal, with contributing editor Roland Kelts and artist Satoshi Kitamura talking about what makes Japanese literature and popular culture click

HARUKI Murakami and Banana Yoshimoto are familiar names in Japanese contemporary writing to Filipinos and the West, more familiar perhaps to the younger generations nowadays than, say, the modern writers such as Yukio Mishima, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki, Kobo Abe, Shohei Ooka, Shusaku Endo and the Nobel laureates Yasunari Kawabata and Kenzaburo Oe.

Older lovers and readers of Japanese fiction and literature may say Filipinos should read the modern writers more (Ooka, for one, wrote the celebrated “Fires on the Plain,” about Japanese soldiers in the Visayas during the Second World War; and Endo, who wrote the novel “Silence,” which no less than Martin Scorsese himself is adapting into a movie, tackled overtly Catholic themes).

But even if younger Filipino readers are enamored of Murakami and Yamamoto, they may also be missing out on other writers in the Japanese contemporary writing scene who are just as qualified to land a best seller on various lists in the West as much as Murakami and the latest hit manga writer and illustrator.

A good way for Filipinos and Japanophiles to get acquainted with other Japanese writers and artists is through the new journal Monkey Business.

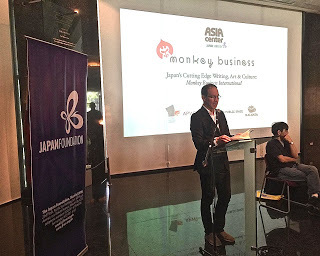

Japan Foundation, Manila hosted a forum last week to introduce to Manila the journal, which was represented by contributing editor Roland Kelts and artist Satoshi Kitamura.

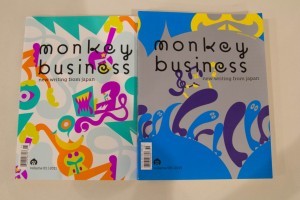

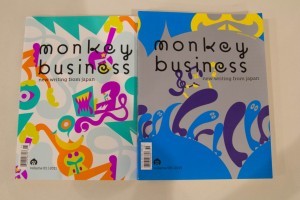

Monkey Business is the only English-language annual of Japanese literature and popular culture in the world. It features different kinds of storytelling styles such as fiction, photography, graphic stories, haiku, tanka and essays.

The magazine selects only the best contemporary writing in Japan, said Kelts. It is edited by Motoyuki Shibata, a professor who is considered Japan’s best translator of American fiction into Japanese.

Among the magazine’s notable contributors are Murakami and Yoko Ogawa.

Japanese writers that have been published in Monkey Business include Aoko Matsuda, Mieko Kawakami, Masatsugu Ono, Mina Ishikawa, Masayo Koike and Yoko Hayasuke.

Exhilarating experience

During the talk “Monkey Business: New Japanese Writing” on Oct. 21 at Ayala Museum, Kelts, a Japanese-American, said he found helping edit and publish Monkey Business an exhilarating experience.

“We hope that through our experiences, we can help other artists and publishers around the world reach a global audience as well,” he said.

Kelts said there were three important lessons he learned in Monkey Business: Publish what you love; get excellent translators; and network with people all over the world.

“I should tell you that we only publish what we love,” Kelts said. “We don’t publish anything because the person is important or famous, and we don’t pretend that this is all of contemporary Japanese culture.”

He said Monkey Business was a hybrid publication with mixed contents from the East and West. Aside from Japanese writers, it has also published the works of Paul Auster, Charles Simic and Kelly Link.

Kelts said publishing the things you loved had a good chance of having people around the world liking your work.

“The translators have to be excellent writers, and they have to love the work that they are translating,” Kelts explained. “They have to live with the work because it is not just a job, it has to be a romance.”

Japanese imagination

Kitamura, who is known for his children’s books and comics, said the Japanese were naturally imaginative. They effortlessly knew how to break away from reality in creating their stories.

Kitamura and Kelts cited the works of animator and filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki. They also cited the fiction of Murakami and the famous animé “Pokemon.”

Kelts explained this imagination of the Japanese could be traced to Shintoism, a religion believing that even inanimate objects can have a spirit.

“In Japanese manga or animé, it can be from pure imagination, purely liberated from the biological world,” Kelts said. “There can be an animé of anything imaginable.”

Kelts mentioned that a popular animated series in Japan, Moyasimon, has some bacteria as its main characters. Kitamura added that he had works centered on a kettle and an overcoat.

Having released its initial volume in 2008, Monkey Business started as purely a journal in Japanese. Later, Shibata and co-editor Ted Goossen tapped Kelts to start the English version in 2010. Five issues in English have since been published.

Monkey Business is materialized through the Nippon Foundation and A Public Space, the magazine’s publisher based in Brooklyn, New York.

The talk was held under the auspices of the Japan Foundation Asia Center.

Visit MONKEY BUSINESS to purchase Monkey Business. Paperbacks and digital copies are available.

Check out Monkey Business

Japan Foundation, Manila hosts a forum on the new literary journal, with contributing editor Roland Kelts and artist Satoshi Kitamura talking about what makes Japanese literature and popular culture click

HARUKI Murakami and Banana Yoshimoto are familiar names in Japanese contemporary writing to Filipinos and the West, more familiar perhaps to the younger generations nowadays than, say, the modern writers such as Yukio Mishima, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki, Kobo Abe, Shohei Ooka, Shusaku Endo and the Nobel laureates Yasunari Kawabata and Kenzaburo Oe.

Older lovers and readers of Japanese fiction and literature may say Filipinos should read the modern writers more (Ooka, for one, wrote the celebrated “Fires on the Plain,” about Japanese soldiers in the Visayas during the Second World War; and Endo, who wrote the novel “Silence,” which no less than Martin Scorsese himself is adapting into a movie, tackled overtly Catholic themes).

But even if younger Filipino readers are enamored of Murakami and Yamamoto, they may also be missing out on other writers in the Japanese contemporary writing scene who are just as qualified to land a best seller on various lists in the West as much as Murakami and the latest hit manga writer and illustrator.

A good way for Filipinos and Japanophiles to get acquainted with other Japanese writers and artists is through the new journal Monkey Business.

Japan Foundation, Manila hosted a forum last week to introduce to Manila the journal, which was represented by contributing editor Roland Kelts and artist Satoshi Kitamura.

Monkey Business is the only English-language annual of Japanese literature and popular culture in the world. It features different kinds of storytelling styles such as fiction, photography, graphic stories, haiku, tanka and essays.

The magazine selects only the best contemporary writing in Japan, said Kelts. It is edited by Motoyuki Shibata, a professor who is considered Japan’s best translator of American fiction into Japanese.

Among the magazine’s notable contributors are Murakami and Yoko Ogawa.

Japanese writers that have been published in Monkey Business include Aoko Matsuda, Mieko Kawakami, Masatsugu Ono, Mina Ishikawa, Masayo Koike and Yoko Hayasuke.

Exhilarating experience

During the talk “Monkey Business: New Japanese Writing” on Oct. 21 at Ayala Museum, Kelts, a Japanese-American, said he found helping edit and publish Monkey Business an exhilarating experience.

“We hope that through our experiences, we can help other artists and publishers around the world reach a global audience as well,” he said.

Kelts said there were three important lessons he learned in Monkey Business: Publish what you love; get excellent translators; and network with people all over the world.

“I should tell you that we only publish what we love,” Kelts said. “We don’t publish anything because the person is important or famous, and we don’t pretend that this is all of contemporary Japanese culture.”

He said Monkey Business was a hybrid publication with mixed contents from the East and West. Aside from Japanese writers, it has also published the works of Paul Auster, Charles Simic and Kelly Link.

Kelts said publishing the things you loved had a good chance of having people around the world liking your work.

“The translators have to be excellent writers, and they have to love the work that they are translating,” Kelts explained. “They have to live with the work because it is not just a job, it has to be a romance.”

Japanese imagination

Kitamura, who is known for his children’s books and comics, said the Japanese were naturally imaginative. They effortlessly knew how to break away from reality in creating their stories.

Kitamura and Kelts cited the works of animator and filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki. They also cited the fiction of Murakami and the famous animé “Pokemon.”

Kelts explained this imagination of the Japanese could be traced to Shintoism, a religion believing that even inanimate objects can have a spirit.

“In Japanese manga or animé, it can be from pure imagination, purely liberated from the biological world,” Kelts said. “There can be an animé of anything imaginable.”

Kelts mentioned that a popular animated series in Japan, Moyasimon, has some bacteria as its main characters. Kitamura added that he had works centered on a kettle and an overcoat.

Having released its initial volume in 2008, Monkey Business started as purely a journal in Japanese. Later, Shibata and co-editor Ted Goossen tapped Kelts to start the English version in 2010. Five issues in English have since been published.

Monkey Business is materialized through the Nippon Foundation and A Public Space, the magazine’s publisher based in Brooklyn, New York.

The talk was held under the auspices of the Japan Foundation Asia Center.

Visit MONKEY BUSINESS to purchase Monkey Business. Paperbacks and digital copies are available.

Published on October 27, 2015 13:28

October 25, 2015

On Japan's "ghost homes," first column for the New Statesman

Out with the old: the ghost homes of Japan

Japan’s shrinking population has produced a different kind of housing problem.

By ROLAND KELTS

I recently visited Aizuwakamatsu, a rural rice-farming region in northern Japan. The scenery was storybook Asia: precipitous hills, dense with greenery, dipping into narrow-cut rice paddies hedged by brooks and streams. At the onset of dusk one evening, our minivan rounded a hillside overlooking the Tadami River. A cluster of homes emerged through the mist, pastel green, pink and pale blue roofs huddled on a patch of land jutting from the shore. With the mountains mirrored in the water surrounding it, the village looked as though it were floating.

One of the local guides told me that the coloured roofs were made of tin or aluminium, covering or entirely replacing the original thatchwork, an icon of traditional Japanese architecture. Upkeep had become too expensive, and the risk of fires or snow collapses too much for elderly inhabitants to bear. But what is really sad, she said, is that no one wants to live here any more. Rural Japan is dying.

Japan boasts the highest female life expectancy (86.8 years) and the world’s greatest number of centenarians per capita (the country is home to 61,568 people aged 100 or older): signs of achievements in health care, diet and societal stability. But it is no net positive. The perfect storm of declining rates of marriage and birth – in 2014 only 1.001 million babies were born, the lowest number since data was first collected in 1899 – is such that Japan’s population is not just ageing faster than anywhere else, it is also disappearing.

One consequence is that the country has an estimated three million deserted homes, according to the Japan Times. The Nomura Research Institute projects that a fifth of all Japanese homes will be abandoned by 2023. Nationwide, residential land prices have plummeted for seven years straight.

The impact of Japan’s greying population has been most evident outside its main cities, where the young can’t find sustainable jobs, whether or not they want them, and so decamp in droves for urban centres.

The opposite is happening in Tokyo, where the population of the metropolitan area has increased for 19 consecutive years, growing by roughly 100,000 in 2014 to 38 million. New high-rise hotels and condos puncture the skyline ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, drawing moneyed young professionals and retirees, as well as free-spending tourists, mostly from China.

But beyond the capital’s glow lies a wasteland of abandoned houses, schools, resorts and theme parks. “The prime reason [abandoned buildings] are legion is because they are in the wrong place,” says Richard Hendy, whose blog Spike Japan documents the decline of the emptying villages and towns. “Emigration to the big cities is the biggest culprit,” he tells me about Japan’s hollowing out. “Absolute household numbers are not expected to peak for about a decade, as more and more people live alone or in one-or two-generation nuclear families with one or no children.”

Hendy adds: “You won’t find abandoned houses in my corner of [Tokyo].”

Cultural sensibilities may also be at play. Japan has long embraced the new over the old. The archetypal Japanese home consists of what westerners would consider transitory materials – wood, paper, straw – not built to last, partly because Japan is buffeted by natural disasters: earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes and typhoons.

Every two decades the Grand Shrine at Ise, among Japan’s most sacred, gets demolished and reconfigured. This summer, the destruction of Tokyo’s beloved modernist Hotel Okura, featured in the Bond novel You Only Live Twice, drew howls of futile protest. A new high-rise with 21st-century amenities will take its place.

Many of the structures now abandoned to rot and ruin – “ghost homes”, in the phrase coined by the New York Times’s Tokyo correspondent Jonathan Soble, in an article this summer – were hastily erected during the postwar years, as Japan’s economic juggernaut took flight. A 30-year lifespan was the standard target. It would make more sense, both technologically and economically, to destroy and build anew, meeting the safety specs of the future and keeping the real-estate market humming.

The postwar imperative to build created a property tax that is today completely at odds with Japan’s real-estate crisis: the government will punish you if you demolish a house without building a new one, raising taxes on your empty land up to six times if you leave it that way.

There are marginal efforts under way to turn the emptied houses into living homes. In Kyoto, the “Machiya [traditional wooden merchant townhouses] Machizukuri Fund” has drawn increasing numbers of overseas investors, attracted by the weak yen and the chance to revive the dying art of a Unesco-blessed aesthetic.

Closer to Tokyo, I met Yoshihiro Takishita, a 72-year-old architect, this summer at his restored farmhouse in the seaside city of Kamakura. He has created a career out of dismantling, moving, restoring and modernising the materials and techniques of Japan’s rural builders. To date, he has completed over 30 projects, spanning four countries.

For Takishita, who discovered his love of traditional Japan with his adoptive father, the late American AP journalist John Roderick, the art of keeping old homes alive is more spiritual than practical. “My kind of a traditional Japanese farmhouse is like a Shinto shrine, a shrine to nature,” he says, as we survey the sea from his pitch-roofed balcony. “Young Japanese only want the cheap and the new. But there is a mystery to the spaces inside these homes that has a healing power. It’s very comforting.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the US” (Palgrave Macmillan). He will be writing regularly from Japan for the New Statesman.

Japan’s shrinking population has produced a different kind of housing problem.

By ROLAND KELTS

I recently visited Aizuwakamatsu, a rural rice-farming region in northern Japan. The scenery was storybook Asia: precipitous hills, dense with greenery, dipping into narrow-cut rice paddies hedged by brooks and streams. At the onset of dusk one evening, our minivan rounded a hillside overlooking the Tadami River. A cluster of homes emerged through the mist, pastel green, pink and pale blue roofs huddled on a patch of land jutting from the shore. With the mountains mirrored in the water surrounding it, the village looked as though it were floating.

One of the local guides told me that the coloured roofs were made of tin or aluminium, covering or entirely replacing the original thatchwork, an icon of traditional Japanese architecture. Upkeep had become too expensive, and the risk of fires or snow collapses too much for elderly inhabitants to bear. But what is really sad, she said, is that no one wants to live here any more. Rural Japan is dying.

Japan boasts the highest female life expectancy (86.8 years) and the world’s greatest number of centenarians per capita (the country is home to 61,568 people aged 100 or older): signs of achievements in health care, diet and societal stability. But it is no net positive. The perfect storm of declining rates of marriage and birth – in 2014 only 1.001 million babies were born, the lowest number since data was first collected in 1899 – is such that Japan’s population is not just ageing faster than anywhere else, it is also disappearing.

One consequence is that the country has an estimated three million deserted homes, according to the Japan Times. The Nomura Research Institute projects that a fifth of all Japanese homes will be abandoned by 2023. Nationwide, residential land prices have plummeted for seven years straight.

The impact of Japan’s greying population has been most evident outside its main cities, where the young can’t find sustainable jobs, whether or not they want them, and so decamp in droves for urban centres.

The opposite is happening in Tokyo, where the population of the metropolitan area has increased for 19 consecutive years, growing by roughly 100,000 in 2014 to 38 million. New high-rise hotels and condos puncture the skyline ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, drawing moneyed young professionals and retirees, as well as free-spending tourists, mostly from China.

But beyond the capital’s glow lies a wasteland of abandoned houses, schools, resorts and theme parks. “The prime reason [abandoned buildings] are legion is because they are in the wrong place,” says Richard Hendy, whose blog Spike Japan documents the decline of the emptying villages and towns. “Emigration to the big cities is the biggest culprit,” he tells me about Japan’s hollowing out. “Absolute household numbers are not expected to peak for about a decade, as more and more people live alone or in one-or two-generation nuclear families with one or no children.”

Hendy adds: “You won’t find abandoned houses in my corner of [Tokyo].”

Cultural sensibilities may also be at play. Japan has long embraced the new over the old. The archetypal Japanese home consists of what westerners would consider transitory materials – wood, paper, straw – not built to last, partly because Japan is buffeted by natural disasters: earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes and typhoons.

Every two decades the Grand Shrine at Ise, among Japan’s most sacred, gets demolished and reconfigured. This summer, the destruction of Tokyo’s beloved modernist Hotel Okura, featured in the Bond novel You Only Live Twice, drew howls of futile protest. A new high-rise with 21st-century amenities will take its place.

Many of the structures now abandoned to rot and ruin – “ghost homes”, in the phrase coined by the New York Times’s Tokyo correspondent Jonathan Soble, in an article this summer – were hastily erected during the postwar years, as Japan’s economic juggernaut took flight. A 30-year lifespan was the standard target. It would make more sense, both technologically and economically, to destroy and build anew, meeting the safety specs of the future and keeping the real-estate market humming.

The postwar imperative to build created a property tax that is today completely at odds with Japan’s real-estate crisis: the government will punish you if you demolish a house without building a new one, raising taxes on your empty land up to six times if you leave it that way.

There are marginal efforts under way to turn the emptied houses into living homes. In Kyoto, the “Machiya [traditional wooden merchant townhouses] Machizukuri Fund” has drawn increasing numbers of overseas investors, attracted by the weak yen and the chance to revive the dying art of a Unesco-blessed aesthetic.

Closer to Tokyo, I met Yoshihiro Takishita, a 72-year-old architect, this summer at his restored farmhouse in the seaside city of Kamakura. He has created a career out of dismantling, moving, restoring and modernising the materials and techniques of Japan’s rural builders. To date, he has completed over 30 projects, spanning four countries.

For Takishita, who discovered his love of traditional Japan with his adoptive father, the late American AP journalist John Roderick, the art of keeping old homes alive is more spiritual than practical. “My kind of a traditional Japanese farmhouse is like a Shinto shrine, a shrine to nature,” he says, as we survey the sea from his pitch-roofed balcony. “Young Japanese only want the cheap and the new. But there is a mystery to the spaces inside these homes that has a healing power. It’s very comforting.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the US” (Palgrave Macmillan). He will be writing regularly from Japan for the New Statesman.

Published on October 25, 2015 10:18

October 24, 2015

Hello, Smith College!

Published on October 24, 2015 18:25

October 21, 2015

Thank you, Manila!

Published on October 21, 2015 21:39

Manila, Pt. 1

Published on October 21, 2015 21:39

October 20, 2015

On the death of Japan's game industry, for The Japan Times

Localization: Has Japan lost the plot?

By ROLAND KELTS

Japan once ruled and defined the global gaming industry. In the arcade age, Japanese developers gave us “Pac-Man,” “Space Invaders” and “Donkey Kong.” In the era of physical consoles: “Metal Gear Solid,” “Snatcher,” “Final Fantasy” and “Silent Hill.” Japan’s creative use of technology, physical design and narrative whimsy once made it the only country in the world that consistently delivered interactive pleasures via buttons and joysticks.

But as veteran American translator, localizer and voice director Jeremy Blaustein reminds me, that was a very long time ago.

Since then, the Japanese gaming industry has grown increasingly marginal in the global market. Costs have soared, technologies advanced exponentially and the Americans overtook the business. Speaking at the Tokyo Game Show in 2009, game creator Keiji Inafune was unequivocal: “Japan is over,” he said. “We’re done. Our game industry is finished.”

For nearly a quarter century, Blaustein has been translating and localizing Japanese video games, anime and television programs, including several shows and movies in the “Pokemon” franchise. He is best known for his work on Konami’s landmark “Metal Gear Solid” game series, whose fifth instalment was released last month to rave reviews.

For nearly a quarter century, Blaustein has been translating and localizing Japanese video games, anime and television programs, including several shows and movies in the “Pokemon” franchise. He is best known for his work on Konami’s landmark “Metal Gear Solid” game series, whose fifth instalment was released last month to rave reviews.

“Metal Gear Solid” was created in the 1990s by star developer Hideo Kojima. Many gamers and journalists cite Blaustein’s 1998 translation and localization of the initial entry as an industry watershed: The first time a video game produced in Japan felt fluently homegrown to English-speaking players.

“The landscape’s really changed a lot from the way it was when I earned those accolades,” Blaustein tells me from his home in Himeji, Hyogo Prefecture, where he now lives with his wife and two children. “There were hardly any American game makers back then. Japanese developers were everything.”

Three key changes transformed the processes of localization into those of globalization: the memory size of games expanded dramatically; the Internet made games more malleable and afforded worldwide access; and game makers became increasingly aware of overseas markets.

This last change, Blaustein believes, has engendered a debilitating self-consciousness in Japanese creators.

“(When Japanese creators) started thinking, ‘Hey, I’m cool,’ they lost their innocence,” he says. “They started thinking about the foreign market instead of making things for themselves. The incredible irony is that what made Japan so desirable (to overseas audiences) was its alienness, and in Japan’s attempt to bridge the gap, that was destroyed.”

Born and raised in Long Island, New York, Blaustein describes his Jewish upbringing as a mix of early Woody Allen/Mel Brooks chaos — “a crazy family of East Coast Jews who yelled at each other over the dinner table. There were no rules. The kids falling asleep in front of the TV. Nobody cared if we brushed our teeth or did our homework.”

He was drawn to the sense of security and the unselfish consideration of others he found in Japanese culture, stunned that anyone at a communal dinner would care if he had a napkin or bother to refill his drink unprompted.

After a brief stint with Jaleco, a Japanese leisure firm, in the early ’90s, Blaustein worked in the international business department at Konami Japan — the lone foreigner in a sea of Japanese staffers.

Back then, he explains, neither the game producers nor their consumers knew what was happening in overseas markets. Localizers and translators had much freer hands. Small adjustments were made to suit parochial minds: a monkey king from Chinese lore transformed into a Native American chief, for example, the former’s magic staff becoming a tomahawk.

Blaustein left Konami and went freelance in 1995. Last month, Kojima left Konami, too, though the company insists it will consider releasing “Metal Gear Solid” games — minus Kojima’s name in the credits.

When he worked on the first “Metal Gear Solid” as a freelance translator in 1998, Blaustein says that his goal was to elevate the text to meet the demands of American fans, most of whom were already deeply familiar with military and spy narratives. “U.S. fans required a more subtle approach to the tropes, combined with a more advanced use of military terminology.” He went so far as to invent military-sounding phrases, such as “on-site procurement (OSP),” to give the game a more authentic feel.

The popularity and creativity of his translation and localization of “Metal Gear” garnered considerable attention, attaining legendary status after the Internet started spreading the word about everything everywhere.

Today, most of the momentum in Japan and the rest of Asia is behind mobile gaming. The region currently dominates the fast-evolving industry. Blaustein is now president of his own game publishing and localization company, iQiOi Co., Ltd, based in Kamakura. It will be releasing its first mobile game early next year.

But he is not betting on a revival of Japanese creativity or global influence.

“Compared with Koreans and Chinese, Japanese are really not very sophisticated with PCs,” he says. “Because they spend so much time on mobile devices, there’s going to be a lot fewer programmers. So, ironically, they’re at a disadvantage when it comes to creating mobile games.”

And his take on the government’s “Cool Japan” campaign? “Well, when you actually ask Japanese people what they think is cool, you usually wind up with Western things.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

By ROLAND KELTS

Japan once ruled and defined the global gaming industry. In the arcade age, Japanese developers gave us “Pac-Man,” “Space Invaders” and “Donkey Kong.” In the era of physical consoles: “Metal Gear Solid,” “Snatcher,” “Final Fantasy” and “Silent Hill.” Japan’s creative use of technology, physical design and narrative whimsy once made it the only country in the world that consistently delivered interactive pleasures via buttons and joysticks.

But as veteran American translator, localizer and voice director Jeremy Blaustein reminds me, that was a very long time ago.

Since then, the Japanese gaming industry has grown increasingly marginal in the global market. Costs have soared, technologies advanced exponentially and the Americans overtook the business. Speaking at the Tokyo Game Show in 2009, game creator Keiji Inafune was unequivocal: “Japan is over,” he said. “We’re done. Our game industry is finished.”

For nearly a quarter century, Blaustein has been translating and localizing Japanese video games, anime and television programs, including several shows and movies in the “Pokemon” franchise. He is best known for his work on Konami’s landmark “Metal Gear Solid” game series, whose fifth instalment was released last month to rave reviews.

For nearly a quarter century, Blaustein has been translating and localizing Japanese video games, anime and television programs, including several shows and movies in the “Pokemon” franchise. He is best known for his work on Konami’s landmark “Metal Gear Solid” game series, whose fifth instalment was released last month to rave reviews.“Metal Gear Solid” was created in the 1990s by star developer Hideo Kojima. Many gamers and journalists cite Blaustein’s 1998 translation and localization of the initial entry as an industry watershed: The first time a video game produced in Japan felt fluently homegrown to English-speaking players.

“The landscape’s really changed a lot from the way it was when I earned those accolades,” Blaustein tells me from his home in Himeji, Hyogo Prefecture, where he now lives with his wife and two children. “There were hardly any American game makers back then. Japanese developers were everything.”

Three key changes transformed the processes of localization into those of globalization: the memory size of games expanded dramatically; the Internet made games more malleable and afforded worldwide access; and game makers became increasingly aware of overseas markets.

This last change, Blaustein believes, has engendered a debilitating self-consciousness in Japanese creators.

“(When Japanese creators) started thinking, ‘Hey, I’m cool,’ they lost their innocence,” he says. “They started thinking about the foreign market instead of making things for themselves. The incredible irony is that what made Japan so desirable (to overseas audiences) was its alienness, and in Japan’s attempt to bridge the gap, that was destroyed.”

Born and raised in Long Island, New York, Blaustein describes his Jewish upbringing as a mix of early Woody Allen/Mel Brooks chaos — “a crazy family of East Coast Jews who yelled at each other over the dinner table. There were no rules. The kids falling asleep in front of the TV. Nobody cared if we brushed our teeth or did our homework.”

He was drawn to the sense of security and the unselfish consideration of others he found in Japanese culture, stunned that anyone at a communal dinner would care if he had a napkin or bother to refill his drink unprompted.

After a brief stint with Jaleco, a Japanese leisure firm, in the early ’90s, Blaustein worked in the international business department at Konami Japan — the lone foreigner in a sea of Japanese staffers.

Back then, he explains, neither the game producers nor their consumers knew what was happening in overseas markets. Localizers and translators had much freer hands. Small adjustments were made to suit parochial minds: a monkey king from Chinese lore transformed into a Native American chief, for example, the former’s magic staff becoming a tomahawk.

Blaustein left Konami and went freelance in 1995. Last month, Kojima left Konami, too, though the company insists it will consider releasing “Metal Gear Solid” games — minus Kojima’s name in the credits.

When he worked on the first “Metal Gear Solid” as a freelance translator in 1998, Blaustein says that his goal was to elevate the text to meet the demands of American fans, most of whom were already deeply familiar with military and spy narratives. “U.S. fans required a more subtle approach to the tropes, combined with a more advanced use of military terminology.” He went so far as to invent military-sounding phrases, such as “on-site procurement (OSP),” to give the game a more authentic feel.

The popularity and creativity of his translation and localization of “Metal Gear” garnered considerable attention, attaining legendary status after the Internet started spreading the word about everything everywhere.

Today, most of the momentum in Japan and the rest of Asia is behind mobile gaming. The region currently dominates the fast-evolving industry. Blaustein is now president of his own game publishing and localization company, iQiOi Co., Ltd, based in Kamakura. It will be releasing its first mobile game early next year.

But he is not betting on a revival of Japanese creativity or global influence.

“Compared with Koreans and Chinese, Japanese are really not very sophisticated with PCs,” he says. “Because they spend so much time on mobile devices, there’s going to be a lot fewer programmers. So, ironically, they’re at a disadvantage when it comes to creating mobile games.”

And his take on the government’s “Cool Japan” campaign? “Well, when you actually ask Japanese people what they think is cool, you usually wind up with Western things.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Published on October 20, 2015 20:10

Live in Manila this week for The Asia Pacific Writers & Translators Conference

Published on October 20, 2015 08:24

October 2, 2015

Reviving Japan by restoring its homes, for The Journal

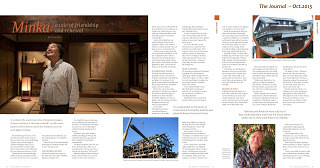

Minka: a tale of friendship and renewal

[photos courtesy of Craig Mod and Yoshihiro Takishita]

To residents of the seaside tourist town of Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, it’s known as “the house on the hill”—an 18th century Japanese minka farmhouse perched atop Genjiyama, one of the town’s highest elevations.

Rumored through the years to be the villa of a former prime minister, the sanctuary of an ocean-worshipping religious cult, even the refuge of a disgraced foreign leader, it is in fact a nearly 300-year-old wooden edifice moved there in the 1960s from the rural Japanese prefecture of Gifu.

The farmhouse was painstakingly rebuilt, restored, and modernized by two men: the late American Associated Press journalist John Roderick and his adopted Japanese son, Yoshihiro Takishita. Today, it’s one of the most beautiful monuments to traditional Japan that is more than just a relic.

Like Father, Like Son

“John and I used to rent a place on the other side of the valley,” Takishita explains, waving his arm.

On a bright hot summer afternoon, we are standing in the front room of his house, cool and shaded, surveying its panoramic views of Kamakura’s scalloped rooftops sloping down to the sea.

Takishita is spry, quick-witted, a mellifluously bilingual 70-year-old with thick black hair and a baritone bellow laugh. He is also bluntly unsentimental.

“We always wanted to have our own house. But back then, [John] was a journalist with no money, and I was a student with no money. What to do?”

Takishita’s adoptive father, Roderick, may have been broke, but he was not unknown. Born in the US state of Maine and a veteran of World War II, he covered the rise of communism in China in the 1940s, living in a cave with Mao Zedong and fellow rebels while filing reports to AP editors in Washington.

Stints in the Middle East and London followed, before he was assigned to Tokyo in the 1950s, to report on a rising American ally and keep an eye on communist China.

Roderick won an award from the AP for journalistic excellence; he was also credited by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai for “opening the door” to China for foreign media. But his book, Minka: My Farmhouse in Japan, published in 2007, a year before he died, may be the pillar of his legacy.

International House

The book chronicles the story of Kamakura’s house on the hill and Roderick’s relationship with Takishita and Japan. It’s a testament to the power of transcultural friendship, and the way physical houses, beautifully made, can become homes.

But it’s also a story about Japan and America. Takishita was inspired to look for a traditional Japanese farmhouse by Texan Meredith Weatherby, publisher of books on Japanese art, and translator of works by Japanese literary icons such as Yukio Mishima.

In the 1950s, Weatherby had erected a traditional Japanese farmhouse in the middle of Roppongi, Tokyo’s foreigner-friendly entertainment district, and it blew Takishita’s mind.

“I came to Tokyo and it was huge, and so many people, and I find this American and his house and I couldn’t believe my eyes when I opened the door,” he says.

“It was an old minka, an old farmhouse, but I opened the door and there was a flush toilet. Wow! Fantastic. Then I went to the kitchen.

“American people are quite open; they show everything in the house. What impressed me the most was the big white icebox—American-made, huge. I’d never seen such a big ‘refrigerator’. ”

Road to Revival

The experience transformed Takishita’s evaluation of his rural Japanese upbringing. All those old hovels from which he’d escaped to Tokyo might be worth something; they might even be the future he and his adoptive father were seeking.

“I just wanted to build a house like Weatherby’s in Roppongi. I told John: We’re wasting our money on rent, when we could live in something beautiful.”

Takishita alerted his snowbound family in Gifu to be on the lookout. Japan in the 1960s was rising and thriving. The 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games brought new money and increasing optimism.

In the summer of 1965, his mother phoned to say she’d found something—an old farmhouse in Issei, Gifu Prefecture that was cobwebbed and falling apart, but would be cheap to buy.

“It was a long drive to reach this village called Issei,” says Takishita. “It was like going to Tibet. It took us forever: winding roads, narrow up and down, climbing near cliffs.

“Finally we reached the village, and to our surprise, it was like a medieval town—only 11 houses. People were looking at us as though we were from Mars.”

Owing to seasonal rains and the release of a dam, Issei was about to be flooded. Townspeople were evacuating; houses would be left to sink into mudslides or rot.

Takishita and Roderick were told by the mayor that if they could dismantle and move the house before winter set in, they could have it for nothing. If they deserted the village without taking the house, they would insult the town.

They had a month—October 1965—Takishita says, before the snows would make the task impossible. With the help of friends, they dismantled the home in Gifu and transported the materials to Kamakura.

But that was just the start.

“At that time, on this big peak in Kamakura, there was no electricity, no [running] water,” Takishita says.

“I said, ‘John: what should we do about living? We need water.’ ‘Never mind,’ John said, pointing up. ‘We’ll catch rain. With this view, we’ll be happy.’”

Window of Hope

Takishita and his wife, Reiko, now have what is likely the most eloquent view of Kamakura, in a house that combines Japanese single-beam artistry with mod cons such as heated Jacuzzi-like baths, Toto washlet bidet toilets, Wi-Fi and leather sofas.

From the outside, the peaked roof and triangular symmetry tell stories of a farming Japan that is fast dying; from the inside, the elegant carpentry and bamboo-lined ceilings speak of a Japan that endures.

Takishita and Roderick are the subjects of a viral short documentary film. Minka: A Farmhouse in Japan, by Davina Pardo, was posted to The New York Times’ website last spring. Pardo’s initial plan was to record Roderick’s story, but the latter died in Hawaii in 2008 before the film was completed. So Takishita became its primary subject, his subsequent work as a restorer of Japan’s farmhouses and the glories of its past the not so subtle subtext.

“I’m happy we did it,” Takishita tells me now. “Because when my father was in his death bed, I asked him, ‘What shall we do with these filmmakers asking these questions?’, and he said, ‘Talk to them.’ His voice was too weak at that time. It’s a shame. He loved to talk.”

The film, Roderick’s book, and Takishita’s own work, a gorgeously photographed, coffee-table tome titled Japanese Country Style: Putting New Life into Old Houses, have ensured that one of Japan’s richest revival stories survives into the 21st century.

As the country hollows out, its population rapidly aging and diminishing, Takishita is an icon of renewal. “Some people still say, ‘Oh, Takishita-san is crazy,’” he tells me as he walks me down the hillside toward Kamakura station.

"And I admit: My kind of Japanese minka farmhouse is a shrine. I guess it’s Shinto, whatever that means to you or to me. All I know is that there is some kind of mystery of the space of these houses that gives a kind of healing power. It’s very comforting."

Published on October 02, 2015 04:37