Roland Kelts's Blog, page 30

September 17, 2015

On the newly legal 'hentai' erotic, pornographic manga/anime site, FAKKU, for The Japan Times

Published on September 17, 2015 09:52

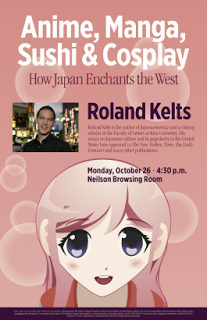

Japanamerica goes to SMITH COLLEGE next month

Published on September 17, 2015 05:11

September 11, 2015

Aizu Tour

Published on September 11, 2015 03:37

September 1, 2015

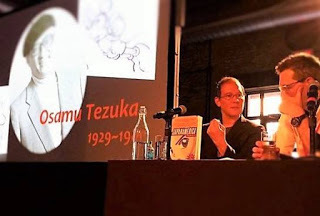

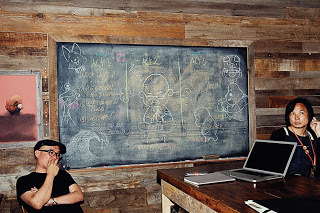

Thanks to Brooklyn, the Wythe Hotel & Waku Waku +NYC

At the Wythe Hotel with Christopher Macdonald. (photo, Susan McCormac Hamaker)

At the Wythe Hotel with Christopher Macdonald. (photo, Susan McCormac Hamaker) (photo, Lawrence Brenner)

(photo, Lawrence Brenner)

Published on September 01, 2015 06:59

August 25, 2015

Speaking & signing in Brooklyn this Sat. 8/29 for "Waku Waku +NYC"

Roland Kelts

AuthorCategory: Anime

"Who is the Real Osamu Tezuka, 'God of Manga & Anime'?"

Panel #305

8.29.2015 3:30pm-4:30pm 60 mins

Location: Wythe Hotel Conference Room

TIX

Roland Kelts was born to an American father and a Japanese mother, and grew up in both America and Japan. Kelts is the author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US, as well as a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo. As a journalist, essayist and columnist, he writes for many publications such as The New Yorker, The Guardian and The Japan Times, and he is an authority on Japan’s contemporary literary and popular cultures. He imparts his unique perspective on Japanese pop culture to the rest of the world as a public speaker and media commentator on CNN, NPR, NHK and the BBC. Most recently, Kelts delivered a TED Talk in Tokyo at TedxHaneda.

Published on August 25, 2015 16:47

August 18, 2015

AKB48 goes American, for The Japan Times

AKB48 turns to an American studio

Director Keishi Otomo and AKB48By

Roland Kelts

Director Keishi Otomo and AKB48By

Roland Kelts

AKB48’s commercial success in Japan is often derided as a sign of the culture’s patriarchal infantilization of women, and the girl group’s inability to appeal to Western audiences a sign of Japan’s increasingly isolated ideas about femininity, sexuality and pop music. Put simply: outside of Japan, AKB48 will never be Psy.

But inside Japan, it’s a reliable moneymaker. Its most recent single, “We Won’t Fight” (Bokutachi wa Tatakawanai), topped the Oricon charts in June. The idol group is the no. 2 bestselling music act in the entire history of Japanese pop music in terms of singles sold. And Japan is the second-largest pop music market in the world – just behind the United States.

Cuteness sells in Japan, especially if it’s well-marketed. Which is why AKB48’s latest music video is puzzling. The ironically titled 12-minute epic, “We Won’t Fight” [short v.], was released this summer. In it, the kawaii (cute) girls are more Ronda Rousey than Sailor Moon.

Cutters Tokyo film editor, Aki MizutaniThe start is standard fare. The girls are featured in a fashion show, dressed as angels. But an alien attack interrupts the proceedings and sends them into a refugee camp. Their environs are suddenly spare, “Walking Dead”-rural. Then they start to fight.

Cutters Tokyo film editor, Aki MizutaniThe start is standard fare. The girls are featured in a fashion show, dressed as angels. But an alien attack interrupts the proceedings and sends them into a refugee camp. Their environs are suddenly spare, “Walking Dead”-rural. Then they start to fight.

The combat scenes are violent: Diminutive Japanese pop idols taking on aliens, kicking, bobbing, weaving, punching.

It’s not what you’d expect, and there’s a reason for that.

Samurai-movie “Rurouni Kenshin” director Keishi Otomo directed the video; it was edited by award-winning studio Cutters, an American post-production studio that opened its first overseas branch in Tokyo three years ago.

Cutters thinks Japan’s advertising industry is out of sync with the rest of the world. Founded in Chicago, and with branches in three other American cities, it’s hoping to change the Japanese model, where domestic giants, such as Dentsu and Hakuhodo, use celebrities to market products, even if they have no connection to the product being hawked.

“I don’t want to insult anybody,” says film editor Aki Mizutani, who worked for two years at the studio’s Los Angeles branch. “But here in Japan, the industry is lazy.”

Cutters is trying to prod Japan out of apathy and into greater creativity. Part of their mission is the AKB48 video, which showcases Japan’s best-selling pop idols behaving like guerrilla group rebels, briefly turning a Japanese female archetype askew.

Trans-cultural collaborations, however, are notoriously shaky. “Afro-Samurai,” the 2007 Japan-U.S. animation project starring Samuel Jackson, tanked.

Mizutani cuts AKB48's "We Won't Fight" (Kosuke Sasaki, photo)

Mizutani cuts AKB48's "We Won't Fight" (Kosuke Sasaki, photo)

Cutters CEO Ryan McGuire, the son of founder Tim McGuire, believes the core of the problem is Japan’s deep aversion to risk. “We’re trying to fight the status quo here,” he says. “Talent is one thing. But what about innovation?”

The prizing of celebrity over creativity in Japan irks McGuire, who says that the country is rife with creative ideas that never get developed.

Mizutani doesn’t think one company can change a culture, but she is hopeful about Cutters’ recent successes. In its first year in Japan, the studio became the only non-Japanese winner of the All Japan Radio and Television Commercial Confederation’s Grand Prix and Craft Awards, for a commercial that was part of Wieden+Kennedy’s Nike Japan campaign.

AKB48 outsells American and European acts in Japan. The Cutters video, which features the girls making Mixed Martial Arts moves, is nearing 3 million views on YouTube. Could it signal a collaborative trans-cultural future for the domestic industry, where creativity and celebrity work in tandem?

For his part, director Otomo was taken aback by the talents and work-ethic of his American partners, and says the experience made him feel more American, at least in spirit.

“I had to negotiate with (AKB48) to get the girls to work on the fight scenes,” he explains. “They are all super busy. It made me wonder how they manage to learn their dance routines. But the Cutters’ office and editing studio were very stylish and relaxing. It was the kind of environment that allowed me to concentrate on my creative work without distraction.”

McGuire adds that the Japanese and American industries approach filmmaking differently. In Japan, the director is saddled with every task, while in the U.S., the director’s raw footage is passed along to an editor, who works together with fellow artists to produce the finished work.

Otomo gave his footage to Mizutani with notes and says he was amazed at how well she captured the nuances of his direction. Even more impressive to him was that she actually seemed to enjoy the process.

“Cutters embodied the feel of the American creative offices I once visited in LA. Their kind of ‘American style’ really suits me. Plus, they always had my favorite beer ready for me after the shoots.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “ Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Director Keishi Otomo and AKB48By

Roland Kelts

Director Keishi Otomo and AKB48By

Roland Kelts

AKB48’s commercial success in Japan is often derided as a sign of the culture’s patriarchal infantilization of women, and the girl group’s inability to appeal to Western audiences a sign of Japan’s increasingly isolated ideas about femininity, sexuality and pop music. Put simply: outside of Japan, AKB48 will never be Psy.

But inside Japan, it’s a reliable moneymaker. Its most recent single, “We Won’t Fight” (Bokutachi wa Tatakawanai), topped the Oricon charts in June. The idol group is the no. 2 bestselling music act in the entire history of Japanese pop music in terms of singles sold. And Japan is the second-largest pop music market in the world – just behind the United States.

Cuteness sells in Japan, especially if it’s well-marketed. Which is why AKB48’s latest music video is puzzling. The ironically titled 12-minute epic, “We Won’t Fight” [short v.], was released this summer. In it, the kawaii (cute) girls are more Ronda Rousey than Sailor Moon.

Cutters Tokyo film editor, Aki MizutaniThe start is standard fare. The girls are featured in a fashion show, dressed as angels. But an alien attack interrupts the proceedings and sends them into a refugee camp. Their environs are suddenly spare, “Walking Dead”-rural. Then they start to fight.

Cutters Tokyo film editor, Aki MizutaniThe start is standard fare. The girls are featured in a fashion show, dressed as angels. But an alien attack interrupts the proceedings and sends them into a refugee camp. Their environs are suddenly spare, “Walking Dead”-rural. Then they start to fight.The combat scenes are violent: Diminutive Japanese pop idols taking on aliens, kicking, bobbing, weaving, punching.

It’s not what you’d expect, and there’s a reason for that.

Samurai-movie “Rurouni Kenshin” director Keishi Otomo directed the video; it was edited by award-winning studio Cutters, an American post-production studio that opened its first overseas branch in Tokyo three years ago.

Cutters thinks Japan’s advertising industry is out of sync with the rest of the world. Founded in Chicago, and with branches in three other American cities, it’s hoping to change the Japanese model, where domestic giants, such as Dentsu and Hakuhodo, use celebrities to market products, even if they have no connection to the product being hawked.

“I don’t want to insult anybody,” says film editor Aki Mizutani, who worked for two years at the studio’s Los Angeles branch. “But here in Japan, the industry is lazy.”

Cutters is trying to prod Japan out of apathy and into greater creativity. Part of their mission is the AKB48 video, which showcases Japan’s best-selling pop idols behaving like guerrilla group rebels, briefly turning a Japanese female archetype askew.

Trans-cultural collaborations, however, are notoriously shaky. “Afro-Samurai,” the 2007 Japan-U.S. animation project starring Samuel Jackson, tanked.

Mizutani cuts AKB48's "We Won't Fight" (Kosuke Sasaki, photo)

Mizutani cuts AKB48's "We Won't Fight" (Kosuke Sasaki, photo)Cutters CEO Ryan McGuire, the son of founder Tim McGuire, believes the core of the problem is Japan’s deep aversion to risk. “We’re trying to fight the status quo here,” he says. “Talent is one thing. But what about innovation?”

The prizing of celebrity over creativity in Japan irks McGuire, who says that the country is rife with creative ideas that never get developed.

Mizutani doesn’t think one company can change a culture, but she is hopeful about Cutters’ recent successes. In its first year in Japan, the studio became the only non-Japanese winner of the All Japan Radio and Television Commercial Confederation’s Grand Prix and Craft Awards, for a commercial that was part of Wieden+Kennedy’s Nike Japan campaign.

AKB48 outsells American and European acts in Japan. The Cutters video, which features the girls making Mixed Martial Arts moves, is nearing 3 million views on YouTube. Could it signal a collaborative trans-cultural future for the domestic industry, where creativity and celebrity work in tandem?

For his part, director Otomo was taken aback by the talents and work-ethic of his American partners, and says the experience made him feel more American, at least in spirit.

“I had to negotiate with (AKB48) to get the girls to work on the fight scenes,” he explains. “They are all super busy. It made me wonder how they manage to learn their dance routines. But the Cutters’ office and editing studio were very stylish and relaxing. It was the kind of environment that allowed me to concentrate on my creative work without distraction.”

McGuire adds that the Japanese and American industries approach filmmaking differently. In Japan, the director is saddled with every task, while in the U.S., the director’s raw footage is passed along to an editor, who works together with fellow artists to produce the finished work.

Otomo gave his footage to Mizutani with notes and says he was amazed at how well she captured the nuances of his direction. Even more impressive to him was that she actually seemed to enjoy the process.

“Cutters embodied the feel of the American creative offices I once visited in LA. Their kind of ‘American style’ really suits me. Plus, they always had my favorite beer ready for me after the shoots.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “ Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Published on August 18, 2015 14:08

August 11, 2015

Talking JAPANAMERICA & ACCESS in Washington, DC

Published on August 11, 2015 17:40

Talking Japanamerica & ACCESS in Washington, DC

Published on August 11, 2015 17:40

August 9, 2015

After Pixar, for The California Sunday Magazine.

After Pixar

In the studio with an Oscar-nominated startup

By Roland Kelts

Photographs by Hiro Tanaka

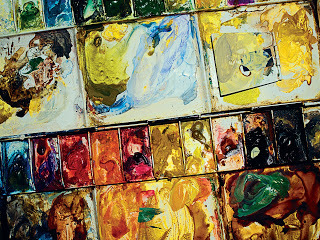

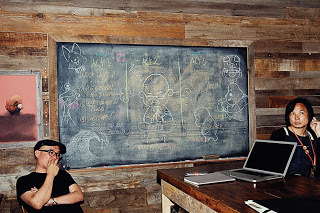

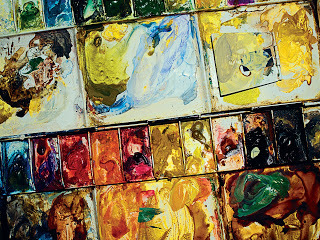

It’s 8 a.m. and the two founders of Tonko House animation studio are preparing to meditate. Their 200-square-foot space at the industrial edge of southwest Berkeley is filled with desktops and laptops, packed bookshelves, paint jars, brushes and carbon markers, and one ten-foot-long work table. There isn’t much room. The table and chairs have been shoved to one side and a heavy beige filing cabinet wheeled into the hallway. For 12 minutes, Daisuke “Dice” Tsutsumi, a wiry Japanese expatriate, and his co-founder, the younger and sturdier Japanese American Robert Kondo, sit lotus style at one end of the room while their business manager, Daisuke “Zen” Miyake, an ordained Buddhist monk, kneels at the other and chants in a droning baritone.

Tsutsumi moved to America more than 20 years ago. Kondo — palms turned upward, index fingers touching thumbs in gyan mudra formation — was born and raised in the San Gabriel Valley, east of Los Angeles. Kondo and Tsutsumi founded Tonko House in February 2014. Their first film, a heartbreaking 18-minute animated short called The Dam Keeper, piled up festival awards. The film was nominated for an Oscar earlier this year.

Tsutsumi and Kondo met as art directors at Pixar, where they were renowned painters. For 7 and 12 years, respectively, they worked in the studio’s Emeryville campus on films like Toy Story 3, Monsters University, and Ratatouille. Last summer, they submitted their resignation letters.

“America and Japan have two of the biggest and most sophisticated animation cultures in world history,” Tsutsumi explains to me, his arms folded over a tight blue apron. “But cultural differences, language abilities, and certain prides and needs … ” He pauses. “They mean that collaboration just hasn’t happened successfully in the past. We think we can create something that’s slightly different from American animation and different from Japanese animation, some kind of hybrid that will bring the two worlds together. We love them both so much.”

As soon as the chanting stops and table and chairs are restored, the lull of Buddhist litanies gives way to chatty chaos. The men discuss budgets (how to cut them), deadlines (how to meet them), and where to get sandwiches for lunch.

Tsutsumi speaks carefully, weighing words, with the faint trace of a Japanese accent. In rigidly patriarchal Japan, Tsutsumi, who is 40, was raised by a single mother in the 1980s, amid the nation’s bubble years, and saw her greeting-card company falter when the bubble burst. “She wasn’t afraid of breaking what you’d call conventions,” he says, “and a lot of people saw her as a kind of feminist symbol.” He moved to the U.S. at 18, when he says he could barely speak English. Enrolled at Rockland Community College in New York, he learned that he had a gift for illustration (“It was easier than English”), and transferred to the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan.

“You look at [Dice’s] paintings and you go, ‘Wow,’” Academy Award–winning Pixar director Pete Docter (Up, Inside Out) told CNN. “He captured life in a way that I’ve never really seen before. It’s got this beauty to it, his sense of lighting, the reflection and warmth in there.”

Kondo is the hyperanimated American — a dervish, quick to laugh and theorize, his eyes bulging as he makes a point. Raised by a third-generation Japanese American father and a Japanese mother, he knew early on that he wanted to draw. “I was a horrible student in high school,” he says. “I really loved drawing and painting.” At Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design, he met a student who had just returned to campus after an internship at Pixar, “and he told me about this amazing place where you could do yoga and everyone was making art that was really expressive and creative.” He applied for a job, and Pixar hired him.

“Dice and Robert both have bold, strong instincts when it comes to the use of light and color. … Their paintings have always been so striking to me,” says Toy Story 3 director Lee Unkrich. “To see them come to life [in The Dam Keeper] while still maintaining the raw sense of handcraftedness was stunning.”

In early 2012, Tsutsumi persuaded Kondo to work with him on a short film, on the side. (As art directors at Pixar, they were not on what Tsutsumi calls the “very narrow path” to directing and telling their own stories.) They wrote four treatments, none of which they liked, so they booked an August weekend in Gualala, in Mendocino County, where they brainstormed and shared childhood memories, some of them intimate and painful. They both remembered feeling like outsiders — being picked on and harassed, but also seeing cruelty inflicted upon others and doing nothing about it. This led them to larger questions about the crime of apathy, of failing to act.

Tsutsumi and Kondo landed on a story that combined their personal wounds and humiliations with the specter of global catastrophe. The principal characters would be a pig, ostracized by his peers, and a fox, a trickster and artist who becomes the pig’s only friend. The setting would resemble a mix of Dutch and Alpine villages, overlooked by the pig’s cavernous home, a windmill whose swirling wheel he diligently winds each morning to keep an encroaching pitch-black smog from smothering the town.

Tsutsumi and Kondo took three-month sabbaticals from Pixar in the spring of 2013. With no outside investors, they poured their personal savings into Tonko House — the word Tonko a nonsensical combination of Japanese words for pig and fox.

To help generate the more than 8,000 digital paintings required to create an 18-minute film, the directors posted a short clip of Pig on Facebook and invited artists to apply for volunteer positions. The invitation was meant for the Bay Area, but applicants from as far away as the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Japan offered to fly to California. Tsutsumi and Kondo pared the list down. By sheer coincidence, they say, the four artists they chose were all from San Jose State. The directors took their volunteers to the Emeryville marina for teaching sessions. They painted the light at sunrise, breakwater rocks, boats bobbing in the harbor. “It wasn’t so much about technique,” Kondo says. “It was more about getting them to see the world the way we do.”

The Dam Keeper’s power sneaks up on you. There is no dialogue. The film is hand-painted with a sketchbook roughness and innocence, like something masterfully drawn to evoke a child’s sensibility. The animation is two-dimensional, a form Hollywood has mostly abandoned, given the commercial success of the three-dimensional computer-generated films pioneered by Pixar, but one that is dear to many animators in Japan — among them director Hayao Miyazaki, animation’s greatest living artist, who happens to be Tsutsumi’s uncle-in-law. The Dam Keeper feels like fairy-tale fare until the weight of apocalypse descends and you realize that a small, intimate account of bullying has become a warning about paralysis in the midst of injustice.

THE FACE OF Toshihiro Nakamura, a young freelance animator based in Daly City, just south of San Francisco, pops up on the computer screen via Skype, a yellow apartment wall close behind him. Tsutsumi and Kondo are reviewing a test clip of Pig, now rendered in Hollywood-style 3-D, in preparation for an imminent presentation to a major studio executive.

In March, First Second Books, an imprint of Macmillan, signed up Tonko House for a retelling of The Dam Keeper as a graphic-novel series that will begin publishing in 2016. The team has also been hired to adapt a popular Japanese children’s book for film. After several trips to Tokyo this spring, they began collaborating with one of the few Japanese studios specializing in 3-D computer-generated animation. And DK, as its creators call it, is being pursued by a handful of Hollywood studios for production as a feature-length film.

Pixar is a hard place to leave. But Tsutsumi and Kondo have never regretted the decision to strike out on their own. “We weren’t there when Pixar was being built. It had already happened,” says Tsutsumi. “Now people are trying to protect the legacy that Pixar has created.” It is such a well-oiled system, and so big, he explains, that it’s almost impossible to fail there — which also means that it’s hard to take the kind of invigorating creative risks that come with making your own art. Work, now, is an adventure.

On the screen, Pig catches a small lamp and then jauntily tosses it into the air.

“I feel like Pig should be trying to catch with both hands, not just one,” says Tsutsumi. “Right now the movement is wrong.” He stands and with notable grace swivels his hips and raises his arms from left to right, mimicking catching and throwing gestures. He looks less like a deskbound animator and more like an actor at rehearsals.

“Realistically,” Kondo says, “we have, like, one day to get this done, right?”

ROLAND KELTS is the author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S. and the forthcoming novel Access. He divides his time between Tokyo and New York.

HIRO TANAKA is based in Tokyo. His first book, Dew Dew, Dew Its, which chronicles U.S. indie-rock, punk, and hardcore bands in America and Europe, won the ShaShin Book Award in 2014.

In the studio with an Oscar-nominated startup

By Roland Kelts

Photographs by Hiro Tanaka

It’s 8 a.m. and the two founders of Tonko House animation studio are preparing to meditate. Their 200-square-foot space at the industrial edge of southwest Berkeley is filled with desktops and laptops, packed bookshelves, paint jars, brushes and carbon markers, and one ten-foot-long work table. There isn’t much room. The table and chairs have been shoved to one side and a heavy beige filing cabinet wheeled into the hallway. For 12 minutes, Daisuke “Dice” Tsutsumi, a wiry Japanese expatriate, and his co-founder, the younger and sturdier Japanese American Robert Kondo, sit lotus style at one end of the room while their business manager, Daisuke “Zen” Miyake, an ordained Buddhist monk, kneels at the other and chants in a droning baritone.

Tsutsumi moved to America more than 20 years ago. Kondo — palms turned upward, index fingers touching thumbs in gyan mudra formation — was born and raised in the San Gabriel Valley, east of Los Angeles. Kondo and Tsutsumi founded Tonko House in February 2014. Their first film, a heartbreaking 18-minute animated short called The Dam Keeper, piled up festival awards. The film was nominated for an Oscar earlier this year.

Tsutsumi and Kondo met as art directors at Pixar, where they were renowned painters. For 7 and 12 years, respectively, they worked in the studio’s Emeryville campus on films like Toy Story 3, Monsters University, and Ratatouille. Last summer, they submitted their resignation letters.

“America and Japan have two of the biggest and most sophisticated animation cultures in world history,” Tsutsumi explains to me, his arms folded over a tight blue apron. “But cultural differences, language abilities, and certain prides and needs … ” He pauses. “They mean that collaboration just hasn’t happened successfully in the past. We think we can create something that’s slightly different from American animation and different from Japanese animation, some kind of hybrid that will bring the two worlds together. We love them both so much.”

As soon as the chanting stops and table and chairs are restored, the lull of Buddhist litanies gives way to chatty chaos. The men discuss budgets (how to cut them), deadlines (how to meet them), and where to get sandwiches for lunch.

Tsutsumi speaks carefully, weighing words, with the faint trace of a Japanese accent. In rigidly patriarchal Japan, Tsutsumi, who is 40, was raised by a single mother in the 1980s, amid the nation’s bubble years, and saw her greeting-card company falter when the bubble burst. “She wasn’t afraid of breaking what you’d call conventions,” he says, “and a lot of people saw her as a kind of feminist symbol.” He moved to the U.S. at 18, when he says he could barely speak English. Enrolled at Rockland Community College in New York, he learned that he had a gift for illustration (“It was easier than English”), and transferred to the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan.

“You look at [Dice’s] paintings and you go, ‘Wow,’” Academy Award–winning Pixar director Pete Docter (Up, Inside Out) told CNN. “He captured life in a way that I’ve never really seen before. It’s got this beauty to it, his sense of lighting, the reflection and warmth in there.”

Kondo is the hyperanimated American — a dervish, quick to laugh and theorize, his eyes bulging as he makes a point. Raised by a third-generation Japanese American father and a Japanese mother, he knew early on that he wanted to draw. “I was a horrible student in high school,” he says. “I really loved drawing and painting.” At Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design, he met a student who had just returned to campus after an internship at Pixar, “and he told me about this amazing place where you could do yoga and everyone was making art that was really expressive and creative.” He applied for a job, and Pixar hired him.

“Dice and Robert both have bold, strong instincts when it comes to the use of light and color. … Their paintings have always been so striking to me,” says Toy Story 3 director Lee Unkrich. “To see them come to life [in The Dam Keeper] while still maintaining the raw sense of handcraftedness was stunning.”

In early 2012, Tsutsumi persuaded Kondo to work with him on a short film, on the side. (As art directors at Pixar, they were not on what Tsutsumi calls the “very narrow path” to directing and telling their own stories.) They wrote four treatments, none of which they liked, so they booked an August weekend in Gualala, in Mendocino County, where they brainstormed and shared childhood memories, some of them intimate and painful. They both remembered feeling like outsiders — being picked on and harassed, but also seeing cruelty inflicted upon others and doing nothing about it. This led them to larger questions about the crime of apathy, of failing to act.

Tsutsumi and Kondo landed on a story that combined their personal wounds and humiliations with the specter of global catastrophe. The principal characters would be a pig, ostracized by his peers, and a fox, a trickster and artist who becomes the pig’s only friend. The setting would resemble a mix of Dutch and Alpine villages, overlooked by the pig’s cavernous home, a windmill whose swirling wheel he diligently winds each morning to keep an encroaching pitch-black smog from smothering the town.

Tsutsumi and Kondo took three-month sabbaticals from Pixar in the spring of 2013. With no outside investors, they poured their personal savings into Tonko House — the word Tonko a nonsensical combination of Japanese words for pig and fox.

To help generate the more than 8,000 digital paintings required to create an 18-minute film, the directors posted a short clip of Pig on Facebook and invited artists to apply for volunteer positions. The invitation was meant for the Bay Area, but applicants from as far away as the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Japan offered to fly to California. Tsutsumi and Kondo pared the list down. By sheer coincidence, they say, the four artists they chose were all from San Jose State. The directors took their volunteers to the Emeryville marina for teaching sessions. They painted the light at sunrise, breakwater rocks, boats bobbing in the harbor. “It wasn’t so much about technique,” Kondo says. “It was more about getting them to see the world the way we do.”

The Dam Keeper’s power sneaks up on you. There is no dialogue. The film is hand-painted with a sketchbook roughness and innocence, like something masterfully drawn to evoke a child’s sensibility. The animation is two-dimensional, a form Hollywood has mostly abandoned, given the commercial success of the three-dimensional computer-generated films pioneered by Pixar, but one that is dear to many animators in Japan — among them director Hayao Miyazaki, animation’s greatest living artist, who happens to be Tsutsumi’s uncle-in-law. The Dam Keeper feels like fairy-tale fare until the weight of apocalypse descends and you realize that a small, intimate account of bullying has become a warning about paralysis in the midst of injustice.

THE FACE OF Toshihiro Nakamura, a young freelance animator based in Daly City, just south of San Francisco, pops up on the computer screen via Skype, a yellow apartment wall close behind him. Tsutsumi and Kondo are reviewing a test clip of Pig, now rendered in Hollywood-style 3-D, in preparation for an imminent presentation to a major studio executive.

In March, First Second Books, an imprint of Macmillan, signed up Tonko House for a retelling of The Dam Keeper as a graphic-novel series that will begin publishing in 2016. The team has also been hired to adapt a popular Japanese children’s book for film. After several trips to Tokyo this spring, they began collaborating with one of the few Japanese studios specializing in 3-D computer-generated animation. And DK, as its creators call it, is being pursued by a handful of Hollywood studios for production as a feature-length film.

Pixar is a hard place to leave. But Tsutsumi and Kondo have never regretted the decision to strike out on their own. “We weren’t there when Pixar was being built. It had already happened,” says Tsutsumi. “Now people are trying to protect the legacy that Pixar has created.” It is such a well-oiled system, and so big, he explains, that it’s almost impossible to fail there — which also means that it’s hard to take the kind of invigorating creative risks that come with making your own art. Work, now, is an adventure.

On the screen, Pig catches a small lamp and then jauntily tosses it into the air.

“I feel like Pig should be trying to catch with both hands, not just one,” says Tsutsumi. “Right now the movement is wrong.” He stands and with notable grace swivels his hips and raises his arms from left to right, mimicking catching and throwing gestures. He looks less like a deskbound animator and more like an actor at rehearsals.

“Realistically,” Kondo says, “we have, like, one day to get this done, right?”

ROLAND KELTS is the author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S. and the forthcoming novel Access. He divides his time between Tokyo and New York.

HIRO TANAKA is based in Tokyo. His first book, Dew Dew, Dew Its, which chronicles U.S. indie-rock, punk, and hardcore bands in America and Europe, won the ShaShin Book Award in 2014.

Published on August 09, 2015 19:23

August 3, 2015

Blue moon with loons

Published on August 03, 2015 18:38