Roland Kelts's Blog, page 24

March 20, 2017

The women behind Asian feminist comic "Monstress", for The Japan Times

Published on March 20, 2017 11:58

March 4, 2017

Anime and folklore in Kyoto, for The Japan Times

Published on March 04, 2017 16:06

July 19, 2016

Anime goes rural with P.A. Works, for The Japan Times

Anime discovers a rural outpost

By ROLAND KELTS

For the past few years, the beginning of July has found me on a flight from Tokyo to Los Angeles to attend Anime Expo (AX), the largest annual North American convention devoted to Japanese popular culture, and its related industry-only event, Project Anime (PA). Both continue to break attendance records. This year, AX tallied 100,420 unique attendees, while PA brought together 102 international anime convention organizers with studio executives and their staff from Japan.

But aside from the personal encounters with the latest crop of cosplayers (anime and manga fans dressed in costume) and other fans, the events afford valuable opportunities to network with industry players and learn how the cultures and their media are changing.

Among first-time participants this year was Progressive Animation Works (P.A. Works), an anime studio unusually based in rural Nanto, Toyama Prefecture. The president and two employees were on hand to celebrate the company’s 15th anniversary, promote the July 4 Netflix worldwide debut of its first mecha series, “Kuromukuro” (Black Corpse), and see what anime’s future may look like outside of Japan.

P.A. Works founder and president, Kenji Horikawa

P.A. Works founder and president, Kenji Horikawa

Over the decades, a herd of studios, including Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli, bought real estate in the relatively inexpensive suburban neighborhoods west and northwest of Tokyo. But Kenji Horikawa, 51, the founder and president of P.A. Works, and a veteran of Tokyo-based industry giants such as Production I.G. and Tatsunoko Productions, promised his wife that they would move to her hometown in Toyama Prefecture when her parents grew old enough to need care.

I sat down with Horikawa in his suite overlooking the Staples Center in downtown LA. It was his first visit to an anime convention in the United States, and he was equal parts rueful and hopeful about the conditions in his industry. He has seen bankruptcy and bubbles, he says. Now he’s focused on anime’s global audience.

“Only one person came with me to Toyama when I opened (the studio),” Horikawa recalls. “Everything was focused on Tokyo, but I didn’t want to follow the trend. I wanted artists to go to rural Japan and do their work there. My idea was to break down the barriers between anime artists and staffers, to create continuity and concentration. I wanted to centralize the creation of anime under one roof.”

At first, no one wanted to leave behind the opportunities of Japan’s dense capital city for an enclave in the countryside. Toyama is on what is known as Japan’s “other coast” — the western shore at the Sea of Japan. Just three applications were submitted.

But as the P.A. Works slowly gained traction, two key subcontracts helped the studio garner respect: Ten years ago, it was commissioned to work on the hit titles “Fullmetal Alchemist” and “Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex.” In 2008, it released a successful original series, “True Tears,” its first as the primary creative studio. Suddenly Toyama was on the anime map.

"Kuromukuro" debuted on Netflix worldwide on July 4

"Kuromukuro" debuted on Netflix worldwide on July 4

“Our artists know that they’re going to a rural region in Japan,” Horikawa says. “If they fail there, they can’t just move to another company in Tokyo. So they have to be committed to making it work. I think that makes our studio superior.”

A more recent effort, the award-winning “Shirobako” (“White Box”), is an anime about anime — a story about five female artists and friends who navigate the daily trials and triumphs of the craft and business. Despite its inside-baseball world, the show has proven surprisingly popular, granting fans a behind-the-scenes look at the challenges of an often difficult business.

P.A. Works studio in Nanto, Toyama-ken

P.A. Works studio in Nanto, Toyama-ken

According to Horikawa, “the biggest problem right now is that our industry lacks artists with skills. It takes five to 10 years to train a good animator. Right now, the demand from domestic and overseas markets is overwhelming us. We have lots of passion, but too little talent.”

As the market expands abroad, P.A. Works is focused on the local: stories that highlight the character of rural Japan and make the tradition-bound regions outside of Tokyo attractive and meaningful. One such series, “Hanasuka Iroha” (“Blossoms for Tomorrow”), features a fictional autumn festival called the Bonbori Matsuri (Paper Lamp Festival) that spawned a real-life counterpart in the Kanazawa seaside hot springs village where the anime is set. The first actual festival, held in October 2010, welcomed 3,000 visitors. For this, its sixth year, organizers expect 10,000.

“Most anime studios are hired guns. They work more like a machine to serve some business goal,” says Miles Thomas, brand data analyst at Crunchyroll, a global streaming site that hosts several titles by P.A. Works and had a prominent presence at this month’s Anime Expo. “But the heads of P.A. Works are intimately involved in what anime they make and why. They demand that the setting be as much of a character as the people who live in it. It’s clear that they love what they’re making, just as as we do.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

By ROLAND KELTS

For the past few years, the beginning of July has found me on a flight from Tokyo to Los Angeles to attend Anime Expo (AX), the largest annual North American convention devoted to Japanese popular culture, and its related industry-only event, Project Anime (PA). Both continue to break attendance records. This year, AX tallied 100,420 unique attendees, while PA brought together 102 international anime convention organizers with studio executives and their staff from Japan.

But aside from the personal encounters with the latest crop of cosplayers (anime and manga fans dressed in costume) and other fans, the events afford valuable opportunities to network with industry players and learn how the cultures and their media are changing.

Among first-time participants this year was Progressive Animation Works (P.A. Works), an anime studio unusually based in rural Nanto, Toyama Prefecture. The president and two employees were on hand to celebrate the company’s 15th anniversary, promote the July 4 Netflix worldwide debut of its first mecha series, “Kuromukuro” (Black Corpse), and see what anime’s future may look like outside of Japan.

P.A. Works founder and president, Kenji Horikawa

P.A. Works founder and president, Kenji HorikawaOver the decades, a herd of studios, including Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli, bought real estate in the relatively inexpensive suburban neighborhoods west and northwest of Tokyo. But Kenji Horikawa, 51, the founder and president of P.A. Works, and a veteran of Tokyo-based industry giants such as Production I.G. and Tatsunoko Productions, promised his wife that they would move to her hometown in Toyama Prefecture when her parents grew old enough to need care.

I sat down with Horikawa in his suite overlooking the Staples Center in downtown LA. It was his first visit to an anime convention in the United States, and he was equal parts rueful and hopeful about the conditions in his industry. He has seen bankruptcy and bubbles, he says. Now he’s focused on anime’s global audience.

“Only one person came with me to Toyama when I opened (the studio),” Horikawa recalls. “Everything was focused on Tokyo, but I didn’t want to follow the trend. I wanted artists to go to rural Japan and do their work there. My idea was to break down the barriers between anime artists and staffers, to create continuity and concentration. I wanted to centralize the creation of anime under one roof.”

At first, no one wanted to leave behind the opportunities of Japan’s dense capital city for an enclave in the countryside. Toyama is on what is known as Japan’s “other coast” — the western shore at the Sea of Japan. Just three applications were submitted.

But as the P.A. Works slowly gained traction, two key subcontracts helped the studio garner respect: Ten years ago, it was commissioned to work on the hit titles “Fullmetal Alchemist” and “Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex.” In 2008, it released a successful original series, “True Tears,” its first as the primary creative studio. Suddenly Toyama was on the anime map.

"Kuromukuro" debuted on Netflix worldwide on July 4

"Kuromukuro" debuted on Netflix worldwide on July 4“Our artists know that they’re going to a rural region in Japan,” Horikawa says. “If they fail there, they can’t just move to another company in Tokyo. So they have to be committed to making it work. I think that makes our studio superior.”

A more recent effort, the award-winning “Shirobako” (“White Box”), is an anime about anime — a story about five female artists and friends who navigate the daily trials and triumphs of the craft and business. Despite its inside-baseball world, the show has proven surprisingly popular, granting fans a behind-the-scenes look at the challenges of an often difficult business.

P.A. Works studio in Nanto, Toyama-ken

P.A. Works studio in Nanto, Toyama-kenAccording to Horikawa, “the biggest problem right now is that our industry lacks artists with skills. It takes five to 10 years to train a good animator. Right now, the demand from domestic and overseas markets is overwhelming us. We have lots of passion, but too little talent.”

As the market expands abroad, P.A. Works is focused on the local: stories that highlight the character of rural Japan and make the tradition-bound regions outside of Tokyo attractive and meaningful. One such series, “Hanasuka Iroha” (“Blossoms for Tomorrow”), features a fictional autumn festival called the Bonbori Matsuri (Paper Lamp Festival) that spawned a real-life counterpart in the Kanazawa seaside hot springs village where the anime is set. The first actual festival, held in October 2010, welcomed 3,000 visitors. For this, its sixth year, organizers expect 10,000.

“Most anime studios are hired guns. They work more like a machine to serve some business goal,” says Miles Thomas, brand data analyst at Crunchyroll, a global streaming site that hosts several titles by P.A. Works and had a prominent presence at this month’s Anime Expo. “But the heads of P.A. Works are intimately involved in what anime they make and why. They demand that the setting be as much of a character as the people who live in it. It’s clear that they love what they’re making, just as as we do.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Published on July 19, 2016 19:55

July 14, 2016

On Hollywood "whitewashing," Scarlett Johansson & "Ghost in the Shell"

My interview with NPR's Eric Molinksy on Hollywood "whitewashing" in its casting of Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kusanagi in the forthcoming adaptation of "Ghost in the Shell." (NB: Her mother will be Japanese, Kaori Momoi.) For Eric's podcast, "Imaginary Worlds."

Published on July 14, 2016 12:26

July 10, 2016

I love LA

Published on July 10, 2016 19:01

June 19, 2016

Frederik L. Schodt and new manga biography, "The Osamu Tezuka Story," for The Japan Times

Drawing on the past of Osamu Tezuka

By ROLAND KELTS

In 1977, American author and translator Frederik L. Schodt and three friends formed a manga-translation group in Tokyo, with the then-quixotic dream of introducing Japanese comics to a global readership. Schodt had arrived in Japan in 1965, courtesy of a father in the United States Foreign Service. He returned in 1970 to attend university after a short stint in the U.S. At the time, manga were everywhere in Japan, he says, and a lot more fun to read than textbooks.

Schodt became addicted to the gag-and-parody series published in boys’ magazines. But one day a friend loaned him a copy of Osamu Tezuka’s epic 12-volume “Phoenix” — and he was stunned. “It made me realize that the work of Japanese manga artists was sometimes approaching the best in literature and film,” he says.

So he and his translation team went straight to Tezuka Productions to get permission for their debut project. To their surprise, the artist, already a celebrity in Japan, known as “the god of manga” for hit titles such as “Astro Boy” and “Black Jack,” greeted them personally and said yes.

The five volumes the group translated by 1978 — without the aid of computers or photocopiers — found no American publisher and gathered dust in Tezuka’s Takadanobaba offices for nearly a quarter century, until Viz Media began releasing them in 2002.

The five volumes the group translated by 1978 — without the aid of computers or photocopiers — found no American publisher and gathered dust in Tezuka’s Takadanobaba offices for nearly a quarter century, until Viz Media began releasing them in 2002.

But Schodt’s relationship with Tezuka continued to evolve. He began serving as the artist’s interpreter during trips outside of Japan, while also translating his work and introducing it to new readers. In 1983, Tezuka wrote the introduction to Schodt’s seminal book, “Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics.”

Now you can find Schodt’s illustrated likeness standing beside Tezuka’s in a panel from “The Osamu Tezuka Story: A Life in Manga and Anime,” a 900-plus page graphic biography that will be published in English for the first time next month.

After appearing in serial form in Asahi Graph, the original Japanese paperback edition of the biography was published in 1992 as “Osamu Tezuka Monogatari,” three years after Tezuka’s death at the age of 60. It was illustrated and authored by Tezuka’s assistant, Toshio Ban, who quotes liberally from Tezuka’s own art and prose, including his autobiography, “Boku wa Mangaka” (“I am a Manga Artist”). The format of the English translation is based on the large-sized paperback of the Japanese original. The translation itself is, of course, by Schodt.

“It is amazing to me that I’m still doing stuff related to (Tezuka),” admits Schodt, who says their 12-year relationship was life-changing. “I’ve felt indebted to him in some ways. I felt he should be better known, and for me personally, this is a way of paying respect to him.”

Readers may recognize Ban’s name from the 2012 manga essay, “I am a Digital Cat,” a collaboration with Tokyo-based British novelist and nonfiction author, Peter Tasker, depicting a dystopian future Japan ruled by robotic cats.

Tasker was already familiar with Ban’s Tezuka resume, and describes the illustrator’s humor combined with a kind of ominousness as “absolutely perfect” for their collaboration. An admirer of Schodt’s books, he says, “I am a huge fan of Tezuka, especially the darker works. You see good people sometimes doing very bad things, and bad people sometimes doing good things. As Schodt has made clear, it’s a tremendously flexible medium capable of dealing with the highest and lowest of themes.”

Advance copies of the English version of Tezuka’s biography, published by Stone Bridge Press, contain only excerpted segments, but it’s clear that Ban is skilled at mimicking his master, evoking his circular designs and shifting, cinematic perspectives.

The story is linear, a chronological narrative of the experiences that shaped Tezuka. A grade school teacher encourages him to keep drawing at an early age. As he struggles to balance art with his medical studies (his father was a doctor), his mother advises him to “choose the path you love.” And as Japan recovers from the war, Tezuka goes to the movies, vowing as a young man to attend the cinema 365 days a year.

Laid bare are many of the roots of Tezuka’s artistic obsessions: birth, death and reincarnation, the brutality of war, the power of mythology and philosophy, literature, medicine and the world of insects. (He incorporated the kanji ideogram for “insect” into his pen name, named his first studio, Mushi Productions, after a Japanese word for “insect,” and created a scathing social satire in the early 1970s called “The Book of Human Insects.”)

For Schodt, translating the biography revealed even more about a man he describes as deeply complex, ambitious, competitive, and relentless in his pursuit of knowledge.

“The biography mentions that he felt like he needed a better reference book to describe insects in his collections. So he actually created these pages of insect drawings, and they’re almost photorealistic, done with ink and pen and in color. He was probably like 12 or 13, and it’s just phenomenal,” says Schodt. “He spent an inordinate amount of time in the woods collecting insects and observing how they lived. Seeing them die, sometimes killing them. Seeing this cruel world of insects and their struggle to stay alive.”

Tezuka’s own life struggle ended far sooner than most expected, and Schodt notes that the biography debunks myths about his public persona. Despite being authorized by Tezuka Productions and produced by his former assistant, “The Osamu Tezuka Story” is no hagiography.

The character at its heart has a prickly temper, frequently embellishes or invents stories to dramatize his personal life and is a manic workaholic rarely seen by his family. Artist Ban’s principal memory of his former boss is summed up in two words: “Always working.”

Yet the diligence has arguably paid off. Tezuka is much better known outside of Japan than he was when he died in 1989, and while he never saw his books published in English during his lifetime, today there are several translations of Tezuka's work available, more than that of any other manga artist. And that’s partly because he created more.

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

By ROLAND KELTS

In 1977, American author and translator Frederik L. Schodt and three friends formed a manga-translation group in Tokyo, with the then-quixotic dream of introducing Japanese comics to a global readership. Schodt had arrived in Japan in 1965, courtesy of a father in the United States Foreign Service. He returned in 1970 to attend university after a short stint in the U.S. At the time, manga were everywhere in Japan, he says, and a lot more fun to read than textbooks.

Schodt became addicted to the gag-and-parody series published in boys’ magazines. But one day a friend loaned him a copy of Osamu Tezuka’s epic 12-volume “Phoenix” — and he was stunned. “It made me realize that the work of Japanese manga artists was sometimes approaching the best in literature and film,” he says.

So he and his translation team went straight to Tezuka Productions to get permission for their debut project. To their surprise, the artist, already a celebrity in Japan, known as “the god of manga” for hit titles such as “Astro Boy” and “Black Jack,” greeted them personally and said yes.

The five volumes the group translated by 1978 — without the aid of computers or photocopiers — found no American publisher and gathered dust in Tezuka’s Takadanobaba offices for nearly a quarter century, until Viz Media began releasing them in 2002.

The five volumes the group translated by 1978 — without the aid of computers or photocopiers — found no American publisher and gathered dust in Tezuka’s Takadanobaba offices for nearly a quarter century, until Viz Media began releasing them in 2002.But Schodt’s relationship with Tezuka continued to evolve. He began serving as the artist’s interpreter during trips outside of Japan, while also translating his work and introducing it to new readers. In 1983, Tezuka wrote the introduction to Schodt’s seminal book, “Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics.”

Now you can find Schodt’s illustrated likeness standing beside Tezuka’s in a panel from “The Osamu Tezuka Story: A Life in Manga and Anime,” a 900-plus page graphic biography that will be published in English for the first time next month.

After appearing in serial form in Asahi Graph, the original Japanese paperback edition of the biography was published in 1992 as “Osamu Tezuka Monogatari,” three years after Tezuka’s death at the age of 60. It was illustrated and authored by Tezuka’s assistant, Toshio Ban, who quotes liberally from Tezuka’s own art and prose, including his autobiography, “Boku wa Mangaka” (“I am a Manga Artist”). The format of the English translation is based on the large-sized paperback of the Japanese original. The translation itself is, of course, by Schodt.

“It is amazing to me that I’m still doing stuff related to (Tezuka),” admits Schodt, who says their 12-year relationship was life-changing. “I’ve felt indebted to him in some ways. I felt he should be better known, and for me personally, this is a way of paying respect to him.”

Readers may recognize Ban’s name from the 2012 manga essay, “I am a Digital Cat,” a collaboration with Tokyo-based British novelist and nonfiction author, Peter Tasker, depicting a dystopian future Japan ruled by robotic cats.

Tasker was already familiar with Ban’s Tezuka resume, and describes the illustrator’s humor combined with a kind of ominousness as “absolutely perfect” for their collaboration. An admirer of Schodt’s books, he says, “I am a huge fan of Tezuka, especially the darker works. You see good people sometimes doing very bad things, and bad people sometimes doing good things. As Schodt has made clear, it’s a tremendously flexible medium capable of dealing with the highest and lowest of themes.”

Advance copies of the English version of Tezuka’s biography, published by Stone Bridge Press, contain only excerpted segments, but it’s clear that Ban is skilled at mimicking his master, evoking his circular designs and shifting, cinematic perspectives.

The story is linear, a chronological narrative of the experiences that shaped Tezuka. A grade school teacher encourages him to keep drawing at an early age. As he struggles to balance art with his medical studies (his father was a doctor), his mother advises him to “choose the path you love.” And as Japan recovers from the war, Tezuka goes to the movies, vowing as a young man to attend the cinema 365 days a year.

Laid bare are many of the roots of Tezuka’s artistic obsessions: birth, death and reincarnation, the brutality of war, the power of mythology and philosophy, literature, medicine and the world of insects. (He incorporated the kanji ideogram for “insect” into his pen name, named his first studio, Mushi Productions, after a Japanese word for “insect,” and created a scathing social satire in the early 1970s called “The Book of Human Insects.”)

For Schodt, translating the biography revealed even more about a man he describes as deeply complex, ambitious, competitive, and relentless in his pursuit of knowledge.

“The biography mentions that he felt like he needed a better reference book to describe insects in his collections. So he actually created these pages of insect drawings, and they’re almost photorealistic, done with ink and pen and in color. He was probably like 12 or 13, and it’s just phenomenal,” says Schodt. “He spent an inordinate amount of time in the woods collecting insects and observing how they lived. Seeing them die, sometimes killing them. Seeing this cruel world of insects and their struggle to stay alive.”

Tezuka’s own life struggle ended far sooner than most expected, and Schodt notes that the biography debunks myths about his public persona. Despite being authorized by Tezuka Productions and produced by his former assistant, “The Osamu Tezuka Story” is no hagiography.

The character at its heart has a prickly temper, frequently embellishes or invents stories to dramatize his personal life and is a manic workaholic rarely seen by his family. Artist Ban’s principal memory of his former boss is summed up in two words: “Always working.”

Yet the diligence has arguably paid off. Tezuka is much better known outside of Japan than he was when he died in 1989, and while he never saw his books published in English during his lifetime, today there are several translations of Tezuka's work available, more than that of any other manga artist. And that’s partly because he created more.

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.

Published on June 19, 2016 08:27

June 9, 2016

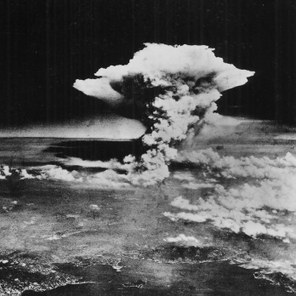

Godzilla returns to Japan after 12 years

Godzilla Resurgence: Japan Reboots Its Most Iconic Monster

After a twelve-year hiatus, Godzilla returns to theaters in Japan this July, and could be more relevant than ever.

By Jonathan DeHart

If the trailer released in April is anything to go by, Godzilla Resurgence (Shin Gojira), could set a new bar for the series.

Set to a dramatic musical score and devoid of dialog, the minute and a half of footage teases viewers with scenes of epic destruction, as Godzilla looms above, swaying what appears to be the largest tail in the series’ history. Fleets of tanks, helicopters and battleships unleash a vicious onslaught of firepower against the gigantic, irradiated lizard – to no avail – as panicked military and government officials frantically formulate a game plan and terrified citizens flee for cover.

As the 29th installment in the monster’s sprawling filmography is being met with widespread anticipation, it begs the question: What gives Godzilla so much staying power?

“Godzilla resonates because it’s a great character, visually, acting-wise, all the ways that characters become great. It is a great anthropomorphic representation of forces beyond human control,” Matt Alt, author of numerous books on Japanese culture, including Yokai Attack!: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide, told The Diplomat.

Yet, as great as Godzilla’s appeal may be, it only goes so far. The film’s co-directors Hideaki Anno (Evangelion) and Shinji Higuchi (Attack on Titan) are keenly aware of the challenges at hand. “Godzilla went through these stages, resetting itself, developing and then succumbing to exhaustion, until it just got so big it had to stop,” Higuchi said.

Higuchi’s solution: Get back to basics. This essentially means casting Godzilla as it was in the original films – a monster hellbent on destroying civilization. In the 1950s this meant drawing on recent memories of Tokyo being razed by Allied bombings. Today, the imagery beamed out to screens across Japan following the natural disasters that have beset Japan in recent years, from Fukushima to Kumamoto, lend gravitas to the scenes of destruction left in Godzilla’s wake, as Alt mused in a recent article for The New Yorker.

“One of the things that’s hard to grasp for foreign audiences is that while the monster is obviously fictional, Japanese don’t see the scenes of destruction as simply just a dramatic backdrop. It’s something that could happen here,” Alt said. “I think that Godzilla Resurgence is going to heavily play up that natural disaster aspect, echoing the fears many Japanese have about the potential for another large-scale earthquake.”

In response to the trailer, Roland Kelts, author of the hit guide to otaku culture, Japanamerica, added: “Shots of the mobilizing blue-suited civil servants and piles of broken planks and debris quite nakedly echo scenes of the aftermath of the great Tohoku earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster.”

In the quest to create such harrowing footage in a believable way, Higuchi has vowed to employ a “hybrid” approach to special effects, involving a mix of cutting-edge computer graphics, an oversized Godzilla doll and actors moving through miniatures. The barrage of artillery featured in the trailer is courtesy of the Japanese military, which agreed to collaborate with the film crew.

Despite growing media attention on the remilitarization of Japan, Alt downplayed the possibility that the Japan Self-Defense Forces’ (JSDF) role in the film could be part of a right-wing agenda. “I think the deployment of the military in this film is rooted less in nationalism and more in the newfound respect for the JSDF that grew out of their rescue efforts during the 2011 tsunami and other disasters,” Alt said. He added: “The directors, and Anno in particular, have a real fetish for military hardware.”

This mélange of production elements leaves no expenses spared, and is a far cry from the methods used to create the original Godzilla films. Kelts is a self-proclaimed fan of the old-school tokusatsu techniques used by Toho Studios in the early days. He fondly recalls a far simpler, inherently comical model of the monster, tramping about a city made of cardboard.

“For me, the ultimate Godzilla of my dreams is the tokusatsu rubber-suited version that aired on late-night TV,” Kelts said. “The sheer physicality of both the creature and the model cities and landscapes was and remains irresistible. And unlike roaring or growling American giant monsters, Godzilla screeched like a strangled bird, which I found far more intimate and haunting.”

He continued: “The tokusatsu Godzilla made me think of a drunken sailor gone to seed, with its pocked, squashed and squinty-eyed face and sagging paunch, swinging blindly at the air, then stomping on stuff just for the hell of it.”

The image of a sailor hints at a deeper point, Kelts noted: “Several Japanese critics have pointed out that the original 1954 Godzilla was meant to embody the enraged spirits of Japan’s dead soldiers, who had been dismissed as losers and forgotten as the country embraced its former American enemy and the spoils of capitalism and Westernization. In the form of Godzilla, those spirits rise from their graves at the bottom of the sea, irradiated and vengeful, and proceed to crush the apartment buildings and office towers of a modernizing Tokyo.”

Today Japan finds itself at a very different crossroads. Embroiled in a number of territorial disputes and a decades long economic malaise, the country is now more focused on maintaining its status as a leader in Asia than wrestling with its nationalistic past.

Given these new realities, Alt said, “I don’t expect the new film to return to the tone of the 1954 film because the regional political calculus has so dramatically shifted.”

Kelts also downplayed the idea that the new film is likely to take on an overtly political tone, saying: “It’s hard for me to speculate without seeing it. [But] if Godzilla starts stomping on foreign tourists in Ginza, or takes a swipe at the tower in Pudong, then we’ll know.”

After a twelve-year hiatus, Godzilla returns to theaters in Japan this July, and could be more relevant than ever.

By Jonathan DeHart

If the trailer released in April is anything to go by, Godzilla Resurgence (Shin Gojira), could set a new bar for the series.

Set to a dramatic musical score and devoid of dialog, the minute and a half of footage teases viewers with scenes of epic destruction, as Godzilla looms above, swaying what appears to be the largest tail in the series’ history. Fleets of tanks, helicopters and battleships unleash a vicious onslaught of firepower against the gigantic, irradiated lizard – to no avail – as panicked military and government officials frantically formulate a game plan and terrified citizens flee for cover.

As the 29th installment in the monster’s sprawling filmography is being met with widespread anticipation, it begs the question: What gives Godzilla so much staying power?

“Godzilla resonates because it’s a great character, visually, acting-wise, all the ways that characters become great. It is a great anthropomorphic representation of forces beyond human control,” Matt Alt, author of numerous books on Japanese culture, including Yokai Attack!: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide, told The Diplomat.

Yet, as great as Godzilla’s appeal may be, it only goes so far. The film’s co-directors Hideaki Anno (Evangelion) and Shinji Higuchi (Attack on Titan) are keenly aware of the challenges at hand. “Godzilla went through these stages, resetting itself, developing and then succumbing to exhaustion, until it just got so big it had to stop,” Higuchi said.

Higuchi’s solution: Get back to basics. This essentially means casting Godzilla as it was in the original films – a monster hellbent on destroying civilization. In the 1950s this meant drawing on recent memories of Tokyo being razed by Allied bombings. Today, the imagery beamed out to screens across Japan following the natural disasters that have beset Japan in recent years, from Fukushima to Kumamoto, lend gravitas to the scenes of destruction left in Godzilla’s wake, as Alt mused in a recent article for The New Yorker.

“One of the things that’s hard to grasp for foreign audiences is that while the monster is obviously fictional, Japanese don’t see the scenes of destruction as simply just a dramatic backdrop. It’s something that could happen here,” Alt said. “I think that Godzilla Resurgence is going to heavily play up that natural disaster aspect, echoing the fears many Japanese have about the potential for another large-scale earthquake.”

In response to the trailer, Roland Kelts, author of the hit guide to otaku culture, Japanamerica, added: “Shots of the mobilizing blue-suited civil servants and piles of broken planks and debris quite nakedly echo scenes of the aftermath of the great Tohoku earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster.”

In the quest to create such harrowing footage in a believable way, Higuchi has vowed to employ a “hybrid” approach to special effects, involving a mix of cutting-edge computer graphics, an oversized Godzilla doll and actors moving through miniatures. The barrage of artillery featured in the trailer is courtesy of the Japanese military, which agreed to collaborate with the film crew.

Despite growing media attention on the remilitarization of Japan, Alt downplayed the possibility that the Japan Self-Defense Forces’ (JSDF) role in the film could be part of a right-wing agenda. “I think the deployment of the military in this film is rooted less in nationalism and more in the newfound respect for the JSDF that grew out of their rescue efforts during the 2011 tsunami and other disasters,” Alt said. He added: “The directors, and Anno in particular, have a real fetish for military hardware.”

This mélange of production elements leaves no expenses spared, and is a far cry from the methods used to create the original Godzilla films. Kelts is a self-proclaimed fan of the old-school tokusatsu techniques used by Toho Studios in the early days. He fondly recalls a far simpler, inherently comical model of the monster, tramping about a city made of cardboard.

“For me, the ultimate Godzilla of my dreams is the tokusatsu rubber-suited version that aired on late-night TV,” Kelts said. “The sheer physicality of both the creature and the model cities and landscapes was and remains irresistible. And unlike roaring or growling American giant monsters, Godzilla screeched like a strangled bird, which I found far more intimate and haunting.”

He continued: “The tokusatsu Godzilla made me think of a drunken sailor gone to seed, with its pocked, squashed and squinty-eyed face and sagging paunch, swinging blindly at the air, then stomping on stuff just for the hell of it.”

The image of a sailor hints at a deeper point, Kelts noted: “Several Japanese critics have pointed out that the original 1954 Godzilla was meant to embody the enraged spirits of Japan’s dead soldiers, who had been dismissed as losers and forgotten as the country embraced its former American enemy and the spoils of capitalism and Westernization. In the form of Godzilla, those spirits rise from their graves at the bottom of the sea, irradiated and vengeful, and proceed to crush the apartment buildings and office towers of a modernizing Tokyo.”

Today Japan finds itself at a very different crossroads. Embroiled in a number of territorial disputes and a decades long economic malaise, the country is now more focused on maintaining its status as a leader in Asia than wrestling with its nationalistic past.

Given these new realities, Alt said, “I don’t expect the new film to return to the tone of the 1954 film because the regional political calculus has so dramatically shifted.”

Kelts also downplayed the idea that the new film is likely to take on an overtly political tone, saying: “It’s hard for me to speculate without seeing it. [But] if Godzilla starts stomping on foreign tourists in Ginza, or takes a swipe at the tower in Pudong, then we’ll know.”

Published on June 09, 2016 04:42

June 6, 2016

Thank you, Taipei

Published on June 06, 2016 08:05

June 1, 2016

Why Japan didn't want an apology for Hiroshima, for KCRW's Press Play on NPR

Published on June 01, 2016 03:54