Roland Kelts's Blog, page 23

October 26, 2017

Anime tourism to save rural Japan, for The Japan Times

Published on October 26, 2017 09:26

October 14, 2017

Otaku culture and the IOEA, for The Japan Times

Published on October 14, 2017 03:30

September 5, 2017

Japan's latest Godzilla movie, for The Guardian

Godzilla shows Japan’s real fear is sclerotic bureaucracy not giant reptiles

By ROLAND KELTS

Five years before the release of Godzilla Resurgence (Shin Godzilla), the first Japanese-made Godzilla movie in more than a decade, Japan’s north-east coastline was slammed by a massive earthquake and tsunami, causing a meltdown at the region’s Fukushima nuclear power plant. Citizens were either misinformed or kept in the dark about the damage: the government would not even use the term “meltdown” until three months later. In an interview with a national newspaper in 2014, novelist Haruki Murakami diagnosed a national character flaw: irresponsible self-victimisation.

“No one has taken real responsibility for the 1945 war end or the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident,” he said. “I’m afraid that it can be understood that the earthquake and tsunami were the biggest assailants and the rest of us were all victims. That’s my biggest concern.”

Resurgence director Hideaki Anno, a revered otaku (nerd) hero best known for creating one of Japan’s darkest and most elaborate anime classics, Neon Genesis Evangelion, doesn’t let his compatriots off the hook, visually or emotionally. Shots of cars and yachts piling up along canals by the force of water pointedly replicate scenes from the 2011 disasters, turning Godzilla into a personified tsunami. Relief workers and politicians in hazmat suits and light blue jumpsuits respectively echo the surreal imagery of the catastrophe’s aftermath.

But during the first half of the film, the monstrosity is neither natural nor imaginary. It’s bureaucracy – specifically, Japan’s sclerotic civil servants, most of whom are men in matching charcoal suits too concerned with protecting their careers and following protocol to risk a decision that might save lives. For them, responsibility is to be shirked at all costs.

These officials and their circuitous exchanges get so much screen time that it’s a relief whenever the eponymous creature rises from the sea or rubble and, unlike the human droids in their corporate uniforms, flexes its reptilian skin, unleashes a trademark birdlike shriek, and actually does something, however disastrous.

“Extermination, capture, and expulsion,” says a ministry official, airing his empty musings as the danger nears Tokyo. To which a fellow suit replies: “Who are you addressing?”

Lampooning bureaucratic inefficiency isn’t unique to Japan, of course. (Gavin Hood’s underappreciated 2015 thriller Eye in the Sky makes similar hay of UK and US officialdom’s tortuous response to impending violence.) But for Japanese audiences, Resurgence’s depiction of paralysed civil servants selfishly fumbling their response to a crisis born of radiation delivered a sharp domestic sting.

Resurgence (Shin Godzilla translates as “new” or “true” Godzilla) was the top box office live-action domestic feature of last year, became the highest grossing of the franchise’s 31 films to date, and won seven Japanese Academy Awards. Murakami’s analysis of his homeland, dramatised on the big screen, resonated most powerfully at home.

The conventional take on the series’ 1954 original is that the monster is a metaphor for America’s nuclear attacks on Japan in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and more recently at the time, the US military’s testing of a hydrogen bomb at Bikini Atoll, whose fallout contaminated a Japanese fishing vessel and resulted in at least one casualty.

But the literary critic Norihiro Kato has argued that Godzilla may also, and perhaps more accurately, be seen as a revenant, an angry and restless symbol of Japan’s estimated 3.1 million soldiers and citizens who perished during the second world war and were quickly cast aside in shame, as the defeated nation embraced its American conquerors (and “a shallow simulacrum of democracy”) through an economic and military alliance that persists to this day. After all, Kato writes, in 31 films spanning six decades, why does the monster always return to Japan? Why not Australia, New Zealand, Singapore?

Kato’s question and interpretation are brought to the foreground in Resurgence – in exasperation, one bureaucrat literally asks: “Why is it coming here again?” Americans appear on the film’s fringes, as condescending, unilaterally minded bureaucrats who carelessly respond with overwhelming force (and the film was made before Donald Trump), and more centrally in the character of Kayoko Anne Patterson, a Japanese-American representative of the US government whose vulgarity and self-regard reveal a wilful ignorance of Japanese etiquette.

But the harshest critique is levelled at Japan. In its portrayal of a people unwilling to speak out or act on their own and a nation paralysed by dependency, Resurgence piles on heaps of destruction that is almost entirely self-inflicted.

• Roland Kelts is a Japanese-American writer and author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US

By ROLAND KELTS

Five years before the release of Godzilla Resurgence (Shin Godzilla), the first Japanese-made Godzilla movie in more than a decade, Japan’s north-east coastline was slammed by a massive earthquake and tsunami, causing a meltdown at the region’s Fukushima nuclear power plant. Citizens were either misinformed or kept in the dark about the damage: the government would not even use the term “meltdown” until three months later. In an interview with a national newspaper in 2014, novelist Haruki Murakami diagnosed a national character flaw: irresponsible self-victimisation.

“No one has taken real responsibility for the 1945 war end or the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident,” he said. “I’m afraid that it can be understood that the earthquake and tsunami were the biggest assailants and the rest of us were all victims. That’s my biggest concern.”

Resurgence director Hideaki Anno, a revered otaku (nerd) hero best known for creating one of Japan’s darkest and most elaborate anime classics, Neon Genesis Evangelion, doesn’t let his compatriots off the hook, visually or emotionally. Shots of cars and yachts piling up along canals by the force of water pointedly replicate scenes from the 2011 disasters, turning Godzilla into a personified tsunami. Relief workers and politicians in hazmat suits and light blue jumpsuits respectively echo the surreal imagery of the catastrophe’s aftermath.

But during the first half of the film, the monstrosity is neither natural nor imaginary. It’s bureaucracy – specifically, Japan’s sclerotic civil servants, most of whom are men in matching charcoal suits too concerned with protecting their careers and following protocol to risk a decision that might save lives. For them, responsibility is to be shirked at all costs.

These officials and their circuitous exchanges get so much screen time that it’s a relief whenever the eponymous creature rises from the sea or rubble and, unlike the human droids in their corporate uniforms, flexes its reptilian skin, unleashes a trademark birdlike shriek, and actually does something, however disastrous.

“Extermination, capture, and expulsion,” says a ministry official, airing his empty musings as the danger nears Tokyo. To which a fellow suit replies: “Who are you addressing?”

Lampooning bureaucratic inefficiency isn’t unique to Japan, of course. (Gavin Hood’s underappreciated 2015 thriller Eye in the Sky makes similar hay of UK and US officialdom’s tortuous response to impending violence.) But for Japanese audiences, Resurgence’s depiction of paralysed civil servants selfishly fumbling their response to a crisis born of radiation delivered a sharp domestic sting.

Resurgence (Shin Godzilla translates as “new” or “true” Godzilla) was the top box office live-action domestic feature of last year, became the highest grossing of the franchise’s 31 films to date, and won seven Japanese Academy Awards. Murakami’s analysis of his homeland, dramatised on the big screen, resonated most powerfully at home.

The conventional take on the series’ 1954 original is that the monster is a metaphor for America’s nuclear attacks on Japan in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and more recently at the time, the US military’s testing of a hydrogen bomb at Bikini Atoll, whose fallout contaminated a Japanese fishing vessel and resulted in at least one casualty.

But the literary critic Norihiro Kato has argued that Godzilla may also, and perhaps more accurately, be seen as a revenant, an angry and restless symbol of Japan’s estimated 3.1 million soldiers and citizens who perished during the second world war and were quickly cast aside in shame, as the defeated nation embraced its American conquerors (and “a shallow simulacrum of democracy”) through an economic and military alliance that persists to this day. After all, Kato writes, in 31 films spanning six decades, why does the monster always return to Japan? Why not Australia, New Zealand, Singapore?

Kato’s question and interpretation are brought to the foreground in Resurgence – in exasperation, one bureaucrat literally asks: “Why is it coming here again?” Americans appear on the film’s fringes, as condescending, unilaterally minded bureaucrats who carelessly respond with overwhelming force (and the film was made before Donald Trump), and more centrally in the character of Kayoko Anne Patterson, a Japanese-American representative of the US government whose vulgarity and self-regard reveal a wilful ignorance of Japanese etiquette.

But the harshest critique is levelled at Japan. In its portrayal of a people unwilling to speak out or act on their own and a nation paralysed by dependency, Resurgence piles on heaps of destruction that is almost entirely self-inflicted.

• Roland Kelts is a Japanese-American writer and author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US

Published on September 05, 2017 02:45

On Japan's latest Godzilla movie, for The Guardian

Godzilla shows Japan’s real fear is sclerotic bureaucracy not giant reptiles

By ROLAND KELTS

Five years before the release of Godzilla Resurgence (Shin Godzilla), the first Japanese-made Godzilla movie in more than a decade, Japan’s north-east coastline was slammed by a massive earthquake and tsunami, causing a meltdown at the region’s Fukushima nuclear power plant. Citizens were either misinformed or kept in the dark about the damage: the government would not even use the term “meltdown” until three months later. In an interview with a national newspaper in 2014, novelist Haruki Murakami diagnosed a national character flaw: irresponsible self-victimisation.

“No one has taken real responsibility for the 1945 war end or the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident,” he said. “I’m afraid that it can be understood that the earthquake and tsunami were the biggest assailants and the rest of us were all victims. That’s my biggest concern.”

Resurgence director Hideaki Anno, a revered otaku (nerd) hero best known for creating one of Japan’s darkest and most elaborate anime classics, Neon Genesis Evangelion, doesn’t let his compatriots off the hook, visually or emotionally. Shots of cars and yachts piling up along canals by the force of water pointedly replicate scenes from the 2011 disasters, turning Godzilla into a personified tsunami. Relief workers and politicians in hazmat suits and light blue jumpsuits respectively echo the surreal imagery of the catastrophe’s aftermath.

But during the first half of the film, the monstrosity is neither natural nor imaginary. It’s bureaucracy – specifically, Japan’s sclerotic civil servants, most of whom are men in matching charcoal suits too concerned with protecting their careers and following protocol to risk a decision that might save lives. For them, responsibility is to be shirked at all costs.

These officials and their circuitous exchanges get so much screen time that it’s a relief whenever the eponymous creature rises from the sea or rubble and, unlike the human droids in their corporate uniforms, flexes its reptilian skin, unleashes a trademark birdlike shriek, and actually does something, however disastrous.

“Extermination, capture, and expulsion,” says a ministry official, airing his empty musings as the danger nears Tokyo. To which a fellow suit replies: “Who are you addressing?”

Lampooning bureaucratic inefficiency isn’t unique to Japan, of course. (Gavin Hood’s underappreciated 2015 thriller Eye in the Sky makes similar hay of UK and US officialdom’s tortuous response to impending violence.) But for Japanese audiences, Resurgence’s depiction of paralysed civil servants selfishly fumbling their response to a crisis born of radiation delivered a sharp domestic sting.

Resurgence (Shin Godzilla translates as “new” or “true” Godzilla) was the top box office live-action domestic feature of last year, became the highest grossing of the franchise’s 31 films to date, and won seven Japanese Academy Awards. Murakami’s analysis of his homeland, dramatised on the big screen, resonated most powerfully at home.

The conventional take on the series’ 1954 original is that the monster is a metaphor for America’s nuclear attacks on Japan in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and more recently at the time, the US military’s testing of a hydrogen bomb at Bikini Atoll, whose fallout contaminated a Japanese fishing vessel and resulted in at least one casualty.

But the literary critic Norihiro Kato has argued that Godzilla may also, and perhaps more accurately, be seen as a revenant, an angry and restless symbol of Japan’s estimated 3.1 million soldiers and citizens who perished during the second world war and were quickly cast aside in shame, as the defeated nation embraced its American conquerors (and “a shallow simulacrum of democracy”) through an economic and military alliance that persists to this day. After all, Kato writes, in 31 films spanning six decades, why does the monster always return to Japan? Why not Australia, New Zealand, Singapore?

Kato’s question and interpretation are brought to the foreground in Resurgence – in exasperation, one bureaucrat literally asks: “Why is it coming here again?” Americans appear on the film’s fringes, as condescending, unilaterally minded bureaucrats who carelessly respond with overwhelming force (and the film was made before Donald Trump), and more centrally in the character of Kayoko Anne Patterson, a Japanese-American representative of the US government whose vulgarity and self-regard reveal a wilful ignorance of Japanese etiquette.

But the harshest critique is levelled at Japan. In its portrayal of a people unwilling to speak out or act on their own and a nation paralysed by dependency, Resurgence piles on heaps of destruction that is almost entirely self-inflicted.

• Roland Kelts is a Japanese-American writer and author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US

By ROLAND KELTS

Five years before the release of Godzilla Resurgence (Shin Godzilla), the first Japanese-made Godzilla movie in more than a decade, Japan’s north-east coastline was slammed by a massive earthquake and tsunami, causing a meltdown at the region’s Fukushima nuclear power plant. Citizens were either misinformed or kept in the dark about the damage: the government would not even use the term “meltdown” until three months later. In an interview with a national newspaper in 2014, novelist Haruki Murakami diagnosed a national character flaw: irresponsible self-victimisation.

“No one has taken real responsibility for the 1945 war end or the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident,” he said. “I’m afraid that it can be understood that the earthquake and tsunami were the biggest assailants and the rest of us were all victims. That’s my biggest concern.”

Resurgence director Hideaki Anno, a revered otaku (nerd) hero best known for creating one of Japan’s darkest and most elaborate anime classics, Neon Genesis Evangelion, doesn’t let his compatriots off the hook, visually or emotionally. Shots of cars and yachts piling up along canals by the force of water pointedly replicate scenes from the 2011 disasters, turning Godzilla into a personified tsunami. Relief workers and politicians in hazmat suits and light blue jumpsuits respectively echo the surreal imagery of the catastrophe’s aftermath.

But during the first half of the film, the monstrosity is neither natural nor imaginary. It’s bureaucracy – specifically, Japan’s sclerotic civil servants, most of whom are men in matching charcoal suits too concerned with protecting their careers and following protocol to risk a decision that might save lives. For them, responsibility is to be shirked at all costs.

These officials and their circuitous exchanges get so much screen time that it’s a relief whenever the eponymous creature rises from the sea or rubble and, unlike the human droids in their corporate uniforms, flexes its reptilian skin, unleashes a trademark birdlike shriek, and actually does something, however disastrous.

“Extermination, capture, and expulsion,” says a ministry official, airing his empty musings as the danger nears Tokyo. To which a fellow suit replies: “Who are you addressing?”

Lampooning bureaucratic inefficiency isn’t unique to Japan, of course. (Gavin Hood’s underappreciated 2015 thriller Eye in the Sky makes similar hay of UK and US officialdom’s tortuous response to impending violence.) But for Japanese audiences, Resurgence’s depiction of paralysed civil servants selfishly fumbling their response to a crisis born of radiation delivered a sharp domestic sting.

Resurgence (Shin Godzilla translates as “new” or “true” Godzilla) was the top box office live-action domestic feature of last year, became the highest grossing of the franchise’s 31 films to date, and won seven Japanese Academy Awards. Murakami’s analysis of his homeland, dramatised on the big screen, resonated most powerfully at home.

The conventional take on the series’ 1954 original is that the monster is a metaphor for America’s nuclear attacks on Japan in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and more recently at the time, the US military’s testing of a hydrogen bomb at Bikini Atoll, whose fallout contaminated a Japanese fishing vessel and resulted in at least one casualty.

But the literary critic Norihiro Kato has argued that Godzilla may also, and perhaps more accurately, be seen as a revenant, an angry and restless symbol of Japan’s estimated 3.1 million soldiers and citizens who perished during the second world war and were quickly cast aside in shame, as the defeated nation embraced its American conquerors (and “a shallow simulacrum of democracy”) through an economic and military alliance that persists to this day. After all, Kato writes, in 31 films spanning six decades, why does the monster always return to Japan? Why not Australia, New Zealand, Singapore?

Kato’s question and interpretation are brought to the foreground in Resurgence – in exasperation, one bureaucrat literally asks: “Why is it coming here again?” Americans appear on the film’s fringes, as condescending, unilaterally minded bureaucrats who carelessly respond with overwhelming force (and the film was made before Donald Trump), and more centrally in the character of Kayoko Anne Patterson, a Japanese-American representative of the US government whose vulgarity and self-regard reveal a wilful ignorance of Japanese etiquette.

But the harshest critique is levelled at Japan. In its portrayal of a people unwilling to speak out or act on their own and a nation paralysed by dependency, Resurgence piles on heaps of destruction that is almost entirely self-inflicted.

• Roland Kelts is a Japanese-American writer and author of Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the US

Published on September 05, 2017 02:45

July 26, 2017

Crunchyroll launches an Anime Con, for The Japan Times

Published on July 26, 2017 20:23

June 30, 2017

May 10, 2017

US cons embrace Japan's rock, for The Japan Times

Anime gives Japanese bands a new route to potential fans

By ROLAND KELTS

‘Retro” was the theme at this year’s Anime Boston, the largest anime convention in the Northeastern United States, and that extended to the event’s featured musical acts: veteran pop duo Puffy AmiYumi and 1960s-styled rock quartet Okamoto’s.

“The only other time we played in Boston we performed a short set in a musical instrument store down the street,” says Okamoto’s lead singer Sho Okamoto during our backstage meeting. “We thought we might have 25 people in the hall today, but there were thousands out there.”

Okamoto’s play top-tier venues in Tokyo. Seeing their name on the roster of an anime convention shows how much more integrated the two media have become.

Anime soundtracks used to travel poorly, with Western fans dismissing the melodramatic scores and lyrics. Songs for TV in particular were often composed to appeal to Japan’s karaoke-driven demographic: Fans would memorize every word and melodic cadence so they could replicate the vocals with friends in an intimate karaoke room.

These days, however, soundtracks are becoming integral to an anime’s overseas appeal. Radwimps, the band that scored Makoto Shinkai’s recent mega-hit “Your Name.,” re-recorded that film’s soundtrack with English lyrics for its Stateside release on April 7. The film is now the highest-grossing anime of all time and Radwimps played a key part.

Puffy AmiYumi, two former idoru (girl idols) now in their 40s, continues to cater to an expanding fan base of anime devotees through soundtrack appearances.

“There are a lot of music lovers in anime fandom, we didn’t really expect that,” says Ami Onuki, one half of the duo. “I think today there’s a deeper connection between anime and music otaku (nerds).”

Her partner, Yumi Yoshimura, adds that anime fans outside of Japan are becoming more accepting of the country’s rock music.

“I don’t think it’s a change in the anime industry in Japan. It’s that fans overseas are giving us a chance to participate in the media they love,” she says.

Decked out in pajama-like onesies, Puffy AmiYumi played a set at Anime Boston that was more raucous guitar rock than conventional J-pop, wowing the packed 3,200-seat Hynes Convention Center, whose crowd included as many teenagers as kids with parents in tow. This is the duo who inspired the Cartoon Network’s hit series “Hi Hi Puffy AmiYumi,” and who sang the opening theme to another popular series, “Teen Titans.” As the crowd roared around me, I felt like I was at a Rihanna concert … minus the erotic innuendo.

I first wrote about Puffy AmiYumi when the pair performed at the 2005 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, a major TV event on the American calendar.

“We heard there were 20,000 people or something and we were happy,” Onuki says, “but it didn’t mean anything until we watched the news. Even on NHK, they said it was a massive event.”

A decade later, Onuki and Yoshimura say U.S. audiences are even more open to foreign music and fashion.

Last month’s Naka-Kon, the largest Japanese anime convention in Middle America, felt like an oasis of global pop culture at the sprawling center of the continent. At my hotel, fans gathered in the lobby the night before Naka-Kon opened, cosplaying and indulging in a culture whose language, ideas, attitudes and media are thousands of kilometers away.

The chief musical act at the event was a neo-gothic five-piece called RondonRats. They wore makeup, at times imitated the Smiths, and thrashed joyfully across the stage before an adoring crowd.

“Compared to the 1980s, when I was a child, I think there is more variety in the style of (Japanese) music, and an increase in the number of artists on major labels collaborating with anime,” says Naka-Kon Director Takuya Jay Inoue. “It seems like more major companies are realizing that there is a market in getting involved with anime music.”

The scenes that played out at Anime Boston and Naka-Kon are being echoed at conventions across the United States and Europe, and the bands that play these events fulfill a Western desire to see and hear a genuinely foreign take on culture. It’s an experience that’s difficult to get when filtered through Western institutions, and Hollywood’s failure with the recent “Ghost in the Shell” reboot may be indicative of that.

“I think one important reason to have (authentic) music performances (at the conventions) is providing that opportunity for the musicians and attendees to connect directly,” Inoue says.

Uniting with anime also gives Japanese musicians a new channel to present themselves to potential fans.

“It’s one thing for attendees to hear the music via the internet or CD, but I think they obtain a more genuine appreciation of the artist when they take time out of their busy schedule to come all the way to Kansas to perform,” Inoue adds.

Still, while conventions help replicate the Japanese pop culture experience, gaps in time and taste remain.

“We love ‘Evangelion,'” says Onuki, referring to the popular anime of the same name. “But no one (at Anime Boston) is cosplaying as Rei Ayanami, our favorite character. So I guess the U.S. will always be a bit different.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a 2017 Nieman fellow in journalism at Harvard University.

By ROLAND KELTS

‘Retro” was the theme at this year’s Anime Boston, the largest anime convention in the Northeastern United States, and that extended to the event’s featured musical acts: veteran pop duo Puffy AmiYumi and 1960s-styled rock quartet Okamoto’s.

“The only other time we played in Boston we performed a short set in a musical instrument store down the street,” says Okamoto’s lead singer Sho Okamoto during our backstage meeting. “We thought we might have 25 people in the hall today, but there were thousands out there.”

Okamoto’s play top-tier venues in Tokyo. Seeing their name on the roster of an anime convention shows how much more integrated the two media have become.

Anime soundtracks used to travel poorly, with Western fans dismissing the melodramatic scores and lyrics. Songs for TV in particular were often composed to appeal to Japan’s karaoke-driven demographic: Fans would memorize every word and melodic cadence so they could replicate the vocals with friends in an intimate karaoke room.

These days, however, soundtracks are becoming integral to an anime’s overseas appeal. Radwimps, the band that scored Makoto Shinkai’s recent mega-hit “Your Name.,” re-recorded that film’s soundtrack with English lyrics for its Stateside release on April 7. The film is now the highest-grossing anime of all time and Radwimps played a key part.

Puffy AmiYumi, two former idoru (girl idols) now in their 40s, continues to cater to an expanding fan base of anime devotees through soundtrack appearances.

“There are a lot of music lovers in anime fandom, we didn’t really expect that,” says Ami Onuki, one half of the duo. “I think today there’s a deeper connection between anime and music otaku (nerds).”

Her partner, Yumi Yoshimura, adds that anime fans outside of Japan are becoming more accepting of the country’s rock music.

“I don’t think it’s a change in the anime industry in Japan. It’s that fans overseas are giving us a chance to participate in the media they love,” she says.

Decked out in pajama-like onesies, Puffy AmiYumi played a set at Anime Boston that was more raucous guitar rock than conventional J-pop, wowing the packed 3,200-seat Hynes Convention Center, whose crowd included as many teenagers as kids with parents in tow. This is the duo who inspired the Cartoon Network’s hit series “Hi Hi Puffy AmiYumi,” and who sang the opening theme to another popular series, “Teen Titans.” As the crowd roared around me, I felt like I was at a Rihanna concert … minus the erotic innuendo.

I first wrote about Puffy AmiYumi when the pair performed at the 2005 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, a major TV event on the American calendar.

“We heard there were 20,000 people or something and we were happy,” Onuki says, “but it didn’t mean anything until we watched the news. Even on NHK, they said it was a massive event.”

A decade later, Onuki and Yoshimura say U.S. audiences are even more open to foreign music and fashion.

Last month’s Naka-Kon, the largest Japanese anime convention in Middle America, felt like an oasis of global pop culture at the sprawling center of the continent. At my hotel, fans gathered in the lobby the night before Naka-Kon opened, cosplaying and indulging in a culture whose language, ideas, attitudes and media are thousands of kilometers away.

The chief musical act at the event was a neo-gothic five-piece called RondonRats. They wore makeup, at times imitated the Smiths, and thrashed joyfully across the stage before an adoring crowd.

“Compared to the 1980s, when I was a child, I think there is more variety in the style of (Japanese) music, and an increase in the number of artists on major labels collaborating with anime,” says Naka-Kon Director Takuya Jay Inoue. “It seems like more major companies are realizing that there is a market in getting involved with anime music.”

The scenes that played out at Anime Boston and Naka-Kon are being echoed at conventions across the United States and Europe, and the bands that play these events fulfill a Western desire to see and hear a genuinely foreign take on culture. It’s an experience that’s difficult to get when filtered through Western institutions, and Hollywood’s failure with the recent “Ghost in the Shell” reboot may be indicative of that.

“I think one important reason to have (authentic) music performances (at the conventions) is providing that opportunity for the musicians and attendees to connect directly,” Inoue says.

Uniting with anime also gives Japanese musicians a new channel to present themselves to potential fans.

“It’s one thing for attendees to hear the music via the internet or CD, but I think they obtain a more genuine appreciation of the artist when they take time out of their busy schedule to come all the way to Kansas to perform,” Inoue adds.

Still, while conventions help replicate the Japanese pop culture experience, gaps in time and taste remain.

“We love ‘Evangelion,'” says Onuki, referring to the popular anime of the same name. “But no one (at Anime Boston) is cosplaying as Rei Ayanami, our favorite character. So I guess the U.S. will always be a bit different.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a 2017 Nieman fellow in journalism at Harvard University.

Published on May 10, 2017 10:17

April 30, 2017

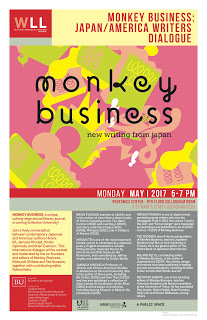

MONKEY meets BOSTON, tomorrow, May 1

Published on April 30, 2017 14:46

April 22, 2017

KOTSUAGE, my story about grief in 2 cultures, for ENDPAIN

KOTSUAGE , by Roland Kelts

Photos by Yuki Iwanami

The doctor's pencil drawing reminded me of one of those Etch A Sketch toys from the 70s. Its gray lines were asymmetrical and squiggly or squared off like sidewalk curbs. Other times they looped up from what I guessed were the body’s nether regions back to the heart.

He held the sheet of paper up to the window’s hazy light. “It’s really just plumbing,” he said.

He was the handsome younger surgeon, swarthy and Mediterranean-looking, and what he was showing us, my younger sister and me, was a solution to the problems they’d found in our father’s chest. Until our meeting that morning, the problem had been singular: an ascending thoracic aortic aneurysm, a swelling of his heart’s central artery that could be life-threatening if untreated.

But when they injected dye into his chest to get a clearer sense of the problem, the problem became plural. The procedure was called a cardiac catheterization, and it transformed his arteries into a colorful subway map, where you could see the blood routes that were slowed or nearly blocked.

“We have to combine the aortic surgery with a double-bypass,” the doctor said. “He has two more blocked arteries, here, and here. We need to create detours for the blood and will need to transplant one artery from his leg. It’s fairly standard. While we have him open, we should fix everything we can.”

“Standard.” “Plumbing.” Hardware fixes for the homeowner. Let Western science and its medical toolkit repair what’s broken in your system. That your father’s life is at risk is logical. That something could go wrong is obvious.

To me, it felt less like standard plumbing than flying: “Fasten your seatbelt, we got bumpy air ahead.” Sure, but that won’t help a whit if the plane goes down. Science knows that it could.

I had flown to Boston a week earlier from Tokyo, Japan, where I live and work for most of the year, to attend the surgery with my America-based Japanese mother and half-Japanese sister. It was April; the entire year had been full of disruptive feelings. Hasty emails of proactive hope (“only 1 to 3% chance of heart failure for men of dad’s age!”) silenced by nights of creeping dread. My family’s humorous optimism, partly an inheritance from my father’s small-town Pennsylvania roots, seemed to vacate us.

Months prior to surgery, when I visited my father at home in Massachusetts during the New Year’s holiday, his eyes would cast floorward in dismay at what was happening to him, to all of us. We used to crank up traditional jazz or swing albums from his lifelong record collection and sip a whiskey or three when I arrived at the house. But the diagnosis of imminent personal danger, the need for surgery, an invasion of his body, the risk and hospitalization meant dark, radical change to a future that long seemed immutable. That quietened him.

Before retiring at 70, he had been a marine biologist, a general ecologist, a botanist, an ornithologist, a professor, and an amateur jazz drummer and fan. The joys and assurances of being able to name the world’s natural wonders, to look at the veins of a leaf and identify the plant family and its history, parse the cadences of birdsong or the bone-chill terror of a wildcat screeching from the trees—his ability to decode all of this was at least one driver of my love of words, sounds, and language.

My mother, too, has always been an ardent reader and communicator. She speaks at least three languages with ease, has taught Spanish at several institutions, and takes visible pride in finding words for thoughts.

Yet the news of my father’s predicament rendered the three of us mute, or worse—cliché-addled and stupid. “We have to take it one day at a time,” I remember myself telling them in the still of their living room, wincing at the banality, fumbling on.

My immediate family’s negotiations with grief and pain were underway. Our track record had been lousy to begin with, so my expectations should have been low.

My paternal grandmother, I, died in a penthouse apartment at the Essex House Hotel in Manhattan in the 1960s. She was taking several antidepressants, and that night she was smoking in bed. She fell asleep and burned to death.

This sent my paternal grandfather, her husband, A, careening. A successful retired industrialist in a small town in Pennsylvania, he stopped playing golf and started drinking heavily, taking up with a young brunette ‘floozy,’ as they used to say, a gold-digger who drank so much that my father and his six siblings nicknamed her “wall-to-wall” to describe her nightly sways. The children and a doctor successfully talked my grandfather off the booze, but he was already damaged and grew ill. A heart attack killed him at 72.

After my grandfather died, my father suffered such severe migraines that he had to pull over onto highway shoulders and grip his temples until they went away. I was too young to understand the symptoms, but I sensed that grief of this intensity could be debilitating.

My Japanese grandparents lived a lot longer—my grandfather died at 94, my grandmother at 100. I lived in their home for a year with my mother when I attended kindergarten in their northern city of Morioka, Japan. They visited our American home several times when my sister and I were growing up, and to us, they were sweet-faced, generous, easy-to-please aliens: we couldn’t understand their native language and culture, but we got the message through smiles, giggles, pats on the head and back, and occasional stiff embraces.

But my mother attended neither of their funerals. Both times she issued terse, hardline excuses—not enough money to make the trip, too busy working right now. It was as if she couldn’t or wouldn’t or was unable to accept and honor their deaths. As a young woman who had left her homeland decades earlier and struggled to assimilate to American culture with an American husband and two US-born children, my mother might have felt that her parents were dead to her years ago. I don’t know.

After open-heart surgery, her husband, my father, was at sea in the ICU. The man who could recite the Latin scientific names for nearly every plant, bird, and furry in the New England forests looked at us blankly when we entered his room, reflexively pushing aside an untouched plate of paper-dry salad.

“I don’t know why they wouldn’t let your call go through!” he said when he saw my face. “I knew you were downstairs the whole time and I told them to let you come up. They were having a pizza party in here last night. Pizza and beer. Jesus.”

I had only just arrived with my mother and sister. We were told not to come until he’d regained consciousness that afternoon. A tall, long-faced nurse with her hair in a towering bun came into the room. Tell them about the pizza party, she said to my father.

“Oh, it went on all night, Roland,” he said. “You wouldn’t believe it.”

And please tell them, the nurse added, that among the very last things we’re allowed to have up here in ICU, besides cocaine and marijuana, are pizza and beer.

More than heartbreaking, the processes of pain are absurd and embarrassing, their nonsense humiliating.

My father recovered from his surgery well. There were a few harrowing days of patching up the infected gash in his left thigh, which had been cut to move the second bypass artery up to his heart, a la the surgeon’s Etch A Sketch. But he seemed to be regaining strength and appetite. He would never ‘be the same,’ the head surgeon had warned us, because open heart surgery ‘takes the starch out of you.’ But he was still here.

A few months later, after I had returned to my life in Tokyo, I got a late-night call from my sister. She was in a car driving to our parents’ home. Our mother had just flown to Canada for a two-week trip, and my sister was on her way to take care of our father. She had called him three times. He wouldn’t pick up the phone.

I called their number from Tokyo at what was midday in New England. No answer. More alarming: no answering machine, no beep.

After a few frantic overseas exchanges, I told her to call the local police. The region was experiencing a midsummer heat wave, with temperatures over 100 F. The cops broke into the house and found my father almost fully naked in a room at the back of the first floor, slumped on the hardwood, perspiring and passed out. TV on, AC off.

An ambulance rushed him to the Emergency Room at a nearby hospital while I scrambled to get a flight to Boston the next day. (Turns out that major airlines have contingency seats for grievance flights, at least if you are a repeat customer. Grief is status.)

When I arrived at his bedside, I recognized my father’s face atavistically: the death mask. He was gray and faded, his eyes hollow even when I could tell that he saw me. He wheezed a ‘hello.’ Speaking seemed Herculean.

He had been infected by a bacterium: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus, MRSA, a staph bacteria resistant to most antibiotics. That’s what the doctors told my sister and me that night, when my father looked already gone, or at least sidling toward the exit. The bacteria were in his spinal column, the neurologist said. They were in his knees.

Couldn’t we just do a little plumbing? I wondered. A little standard stuff?

But my father’s face said otherwise. You learn what dying is just as you learn about living: you confront it, stretch your muscles, learn to accommodate. You don’t learn from mistakes, I once read. You just learn what they feel like.

I learned the look of death in my American father’s face from my Japanese grandmother. I went to her funeral in my mother’s stead and arrived in Morioka from Tokyo at the end of her wake. She was laid out under sheets and bearing a tight kimono, something I’d never seen her wear, and she was horribly made-up but defined by her absence. In Japanese, it’s called the tsuya, the passing of night. I sat with my uncle and aunt and three cousins. We were listening to her silence.

Writing this now, I am embarrassed by my weak nerves and emotional incompetence. I took the Shinkansen bullet train from Tokyo to Morioka, and in the taxi from the station to the Buddhist temple where she would be cremated and memorialized, I couldn’t tie my tie. I mean: I forgot how to tie a tie.

I texted my girlfriend in Tokyo, and she pointed me to a step-by-step website on tie tying. I had to concentrate hard to figure it out. None of the folds made sense, and I was nearly choking myself with crooked knots. The driver eyed me in the rearview mirror. I called my girlfriend minutes before arriving at the temple, and she walked me through the basics. I had tied ties for three decades. Suddenly, I’d forgotten how to do it.

Japanese funerals are largely Buddhist in ritual, though it’s a very distinct version of the religion that arrived from 6th century East Asia, colored by Japan’s polytheistic and animistic national faith, Shinto. The emphasis is on daily presence in nature, not scripture, ritual versus study. Japan can be simultaneously rigid in its behavioral norms and deeply sentimental.

In the temple, I fingered my juzu (prayer beads) during the chanting of the monks, which sounded like humans trying to be cicadas. It was a buzz, a gravelly buzz, and I tried to take comfort in what felt like urgent sadness. My grandmother, this woman, this soul, was gone, it seemed to say, and death is present. Stay alert. Pay attention.

And then came the closest encounter with the realms of both passage and presence that I could imagine: kotsuage. This is a ritual that makes death feel like it’s inside you. What happens: You and your family, in my case, me and my Japanese uncle, aunt and three cousins, retrieve from the ashes of cremation, the bone fragments of your relative—in this case, our grandmother, our mother.

The fire is still burning in the far corner. The ashes are freshly deposited. I am using chopsticks. I am connecting those chopsticks with my cousins, my uncle, and aunt, to my grandmother’s bones. In Japan, this is the only occasion on which two people are supposed to clasp the same item with their chopsticks. To do so in any other setting is sacrilege.

We are delivering her bones to an urn.

When I first learned of this ritual from my cousin, I begged out. I lacked the requisite physical delicacy, I’d told him, picturing my fat American fingers squeezing too hard, sending a bone fragment flicking through the air, knocking an urn to the floor. I couldn’t do it, I’d said. I can’t.

But the experience stirred feelings that grew peaceful and intensely intimate. I was touching my grandmother, participating in her transformation less from something into nothing, but from something into a something else. There was just us: me, my family, grandmother.

My grandparents lived most of their lives and died in Tohoku, the mountainous territory of northern Japan, years before its Pacific coastline was severely and in many cases irrevocably damaged by the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disasters of 2011. My grandmother’s family were farmers, once-wealthy landowners from Akita, a city on the main island of Honshu’s west coast, at the Sea of Japan. My grandfather was the son of a Bushido samurai family from Esashi, a mountain village just south of Morioka, the capital city of Iwate, on Japan’s eastern Pacific coast.

In the five years since the triple disasters, over 18,000 are officially tallied as perished, some two to three-thousand of whose bodies have not yet been found. Tohoku and Iwate, its northeastern prefecture, are Japanese place names I once associated with my year in a local kindergarten and the rural roots of my Japanese family. Now they are destinations for relief workers, demolition crews and journalists like me.

Last year, I visited Fukushima Prefecture’s Minami-soma, one of the most brutally devastated of Tohoku’s coastal towns, to meet Takayuki Ueno, a 43-year-old farmer-turned-victims’ advocate and local educator. The Ueno family’s presence on the land dates back generations. Standing at sunset beside his new home (built three years ago and ten yards from where his old one was destroyed), at the edge of puddled rice paddies wedged between leafy hills to the west and the sea to the east, it’s not hard to understand why he is staying.

Like many in constant trauma, he recounts the tragic events hour-by-hour, sometimes minute-to-minute—the calm after the earthquake, the sirens warning of a wave 9-feet high that rose 60 feet, the water surrounding and blocking his return home—as if they happened just yesterday, despite the five years of recovery and debris cleanup, his spacious and very modern new home, and a cherubic 4-year-old daughter, Sally, born five months after the disasters. Ueno is seated across from me on the floor at a low coffee table, a lean man with an athletic build who chain-smokes aggressively, as if in competition. “I started doing this after the tsunami,” he says, half grinning as he stubs out one cigarette and reflexively lights another. “Now I can’t stop.”

The bodies of his father and son remain missing. On select monthly Sundays, Ueno searches on a beach near the town of Okuma, a few miles south of Fukushima Daiichi, the most badly damaged of the area’s nuclear reactors. Local residents and government-hired construction workers often join him (the latter illegally using government-issued bulldozers and mining shovels), helping him dig through heaps of natural and man-made wreckage on the seashore for a fragment of bone, teeth, or tuft of hair that might be DNA-tested and verified.

Ueno believes that his son’s body, in particular, may have drifted down the coastline in the aftermath of the tsunami waves and washed up on one of the beaches. But at the time, he was prohibited from searching those beaches by local police and government authorities, because they were inside the zone designated most radioactive.

“It was a time of extreme effort,” he says after a long pause and exhalation of smoke. “The priority of a parent is to defend the child from anything and everything. I couldn’t save or protect my kids, so I thought I was the worst parent for a long time. I could’ve saved them, I kept telling myself, but the fact was, I couldn’t. When I found Erika’s body, I held her in my arms, and I apologized to her. I still need to apologize to Kotaro. I think if I had found Kotaro at the time, and if I’d looked into his face, I would have killed myself.”

The butsudan (family altar) in his house bears four football-sized ceramic urns, one for his mother, father, daughter, and son, arranged in a horizontal line behind portraits of each. Two of the urns are filled with cremated ashes from a kotsuage Buddhist ritual, in which the larger bones are separated from the ash by surviving family, like the one I experienced at my grandmother’s funeral, held at a nearby temple exactly one year after the tsunami. The other two remain empty.

Ueno is still angry. First, he had to get over the initial spike of rage he felt toward his parents.

Immediately after the magnitude 9.0 earthquake, at 2:46 p.m., they called their grandchildren’s hillside school and were told that all were safe. But since the building might have sustained structural damage, the children should be picked up and returned to their homes immediately.

Ueno was working at a farm cooperative a few miles inland. His wife, Kiho, was a nurse at a local hospital, also miles from the sea and nestled in the hills. His parents were told to get the children out of the precarious school building and bring them to his home, less than a mile from the coast. Fifty minutes later, at 3:38 p.m., when his wife was on the phone with his mother to confirm their safety, a 60-foot wave swept through that home, washing away its first floor and most of its second, making them all tsunami casualties.

(To this day, Kiho believes she heard a female scream, but she’s not sure who it was—her mother-in-law, or her daughter, before the line went dead.)

“At first I just blamed them,“ Ueno says. “I felt a kind of hatred. Why did you let my children die? But later I thought that Erika loved her grandma so much, and Kotaro loved his grandpa. My wife and I were working that day, so my parents were helping us raise them. They were doing what they were supposed to do. So one time I thought: well, my kids are with their grandparents now, so maybe my parents are still taking care of my kids.”

But his anger toward the Japanese government, the nuclear industry, and Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the operators of the power plant, is inconsolable. That the energy generated by the facility was used to power Tokyo’s moneyed and what he calls “wasteful” residents, and not the people of Tohoku and Fukushima, who continue to suffer its poisons, is “offensive and humiliating.” That their officially sanctioned incompetence prevented him from searching for the bodies of his son and father in the crucial days after the catastrophe, he finds unforgivable.

“It was their nuclear plant that caused the 12-mile exclusion zone,” he says, shaking his head. “I still imagine how many bodies may have been on those beaches.”

During our conversation, Kiho has been weeding the local grounds—something she does when they are unable to farm, when nothing is growing. But suddenly the door opens, and Kiho enters with their daughter, Sally, who has just returned from school.

Ueno is getting tired, smoking a little more slowly, his eyes blinking against emotional fatigue. “I know for certain that if my wife wasn’t pregnant then, and if my daughter hadn’t been born that October, we wouldn’t have a family now. Maybe I wouldn’t be here.”

Sally brushes past her mother and pauses in the living room to take in the scene, nods her quick acknowledgment of me, the foreign journalist, then swiftly turns toward the family altar. There, she bows low before each urn and portrait, pausing to greet the four members of her family that she’s never met. “Hello, grandpa. Hello, grandma. Hello, sister. Hello, brother.”

Then she takes a few steps back and shouts, “Tadaima!” “I’m home!”

Published on April 22, 2017 13:37

April 10, 2017

My live convo with Makoto Shinkai, creator of "your name."

Published on April 10, 2017 00:09