Roland Kelts's Blog, page 21

June 20, 2018

Why Japan's lit and culture are so vibrant today

Times Literary Supplement: Japanese questions of the soul

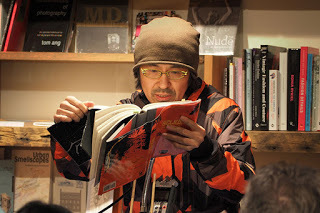

At public readings, either in Japanese or English, the novelist Hideo Furukawa performs like a banshee. He voices his characters’ personae, tenor shifting from stentorian to hushed, growling, trilling, book held aloft in his quivering left hand. His compact frame rocks to and fro, slowly enlarging before your eyes as he rises on his toes and raises his arm into a broad arc, snug hipster beanie barely holding his cranium in place.

I have watched Furukawa read several times, in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles and Tokyo, and each time I have been unable to look away. At first I worried that his histrionics might be overkill. But then I re-read his prose. He writes like a banshee, too, forcing words into action, squeezing them for meaning, studding his lines with coinages such as “scootscootscoot” and “creekeek” when the words just can’t take it anymore.

At fifty-one, Furukawa is among the generation of Japanese writers I’ll call “A. M.”, for “After Murakami”. Haruki Murakami is Japan’s most internationally renowned living author. His work has been translated into over fifty languages, his books sell in the millions, and there is annual speculation about his winning the Nobel Prize. Over four decades, he has become one of the most famous living Japanese people on the planet. It’s impossible to overestimate the depth of his influence on contemporary Japanese literature and culture, but it is possible to characterize it.

Read More >>

At public readings, either in Japanese or English, the novelist Hideo Furukawa performs like a banshee. He voices his characters’ personae, tenor shifting from stentorian to hushed, growling, trilling, book held aloft in his quivering left hand. His compact frame rocks to and fro, slowly enlarging before your eyes as he rises on his toes and raises his arm into a broad arc, snug hipster beanie barely holding his cranium in place.

I have watched Furukawa read several times, in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles and Tokyo, and each time I have been unable to look away. At first I worried that his histrionics might be overkill. But then I re-read his prose. He writes like a banshee, too, forcing words into action, squeezing them for meaning, studding his lines with coinages such as “scootscootscoot” and “creekeek” when the words just can’t take it anymore.

At fifty-one, Furukawa is among the generation of Japanese writers I’ll call “A. M.”, for “After Murakami”. Haruki Murakami is Japan’s most internationally renowned living author. His work has been translated into over fifty languages, his books sell in the millions, and there is annual speculation about his winning the Nobel Prize. Over four decades, he has become one of the most famous living Japanese people on the planet. It’s impossible to overestimate the depth of his influence on contemporary Japanese literature and culture, but it is possible to characterize it.

Read More >>

Published on June 20, 2018 19:30

June 15, 2018

JAPANAMERICA for 600 bucks?

Published on June 15, 2018 04:09

June 14, 2018

Talks, readings, signings in Dallas at AnimeFest, August 2018

Published on June 14, 2018 01:03

May 31, 2018

Me and my Monkey: my story behind Monkey Business: New Writing from Japan

via GLLI

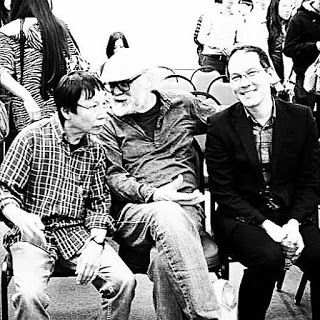

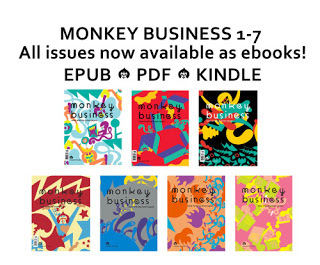

Editor’s note: Forget the old saw that English language readers won’t read literature in translation. For the last seven years, Monkey Business: New Writing from Japan has been publishing an annual journal of what it calls “the best of contemporary Japanese literature” in English. The paperback editions of the first three issues were completely sold out. This year, though, for reasons the editors call “both professional and personal,” it will not be releasing a new edition. Monkey Business will return with issue no. 8 in 2019 but the digital and most paperback editions of issues 1-7 are available for purchase at its online store. I asked Roland Kelts, who has been involved with the journal since its founding, to tell us about Monkey Business and his connection to Japanese literature in translation.

Eight years ago I had the good fortune of being asked to do a favor. Professors Motoyuki Shibata and Ted Goossen, esteemed literary translators, invited me to dinner in Tokyo and asked if I could help find a North American partner for their venture: an annual English-language journal of Japanese literature.

Back in New York City, my home in America, I called Brigid Hughes, founding editor of A Public Space. (Brigid had commissioned me and Shibata to assemble a portfolio on Japanese fiction for her first issue.) We had lunch in Soho, Brigid said yes, and off we went.

Our partnership has since produced seven issues of Monkey Business: New Writing from Japan (MBI). They contain stories, poems, photo essays and manga by talents internationally renowned (Yoko Ogawa, Haruki Murakami), fast rising (Hideo Furukawa, Mieko Kawakami), and those we’ll be seeing more of (Tomoka Shibasaki, Aoka Matsuda). Each issue is unpredictable and spiked with gems – what author Junot Diaz calls “an astonishment.”

In my role as MBI advisor, contributing editor and occasional road manager, the experience has been equal parts astonishment and education.

When I first read literature in translation (Dostoevsky, Kafka), the alchemy was transparent to me. I’m embarrassed to admit that as a teenager, I didn’t even know the prose had been translated, or at least I didn’t care. I just knew that the writers’ names sounded strange and cool. It felt like they were writing directly to me.

At Oberlin, poet and translator David Young taught me to think about the sound and shape of language beyond its content, which in turn made me think of its origin – not only in thought, but also in culture, place, and time. I remember learning that Ezra Pound claimed he could understand Chinese ideograms without formal study and thinking … wha?

Context is everything, and also, like a Zen koan, nothing.

After I moved to Japan and met Haruki Murakami, I asked him several questions about translation. He likened the process to living inside an author’s mind. Of J.D. Salinger’s mind, he once said while translating The Catcher in The Rye: “It’s very dark in there. That novel (Catcher) is a battle between the open world and the closed. That’s the tension. And in the end, its author chose the closed world.”

I’d never thought of the book in precisely those terms, as an internalized contest between the messiness of democratic tolerance (of the ‘phonies,’ the winners and jocks and fusty clueless schoolteachers) and the dignity and purity of authoritarian control. Through translating one of my favorite American novels, Murakami, a Japanese author, had uncovered a dark violence at its heart that I, an American reader, had never directly confronted.

Working alongside Shibata and Goossen and their team of writers and translators (Jay Rubin, Hitomi Yoshio, Michael Emmerich and David Boyd among the many) on MBI has produced similar revelations. As with the creation of it, the translation of literature is a labor of love and serious play. Matching author and translator has as much to do with sheer passion as it does with proclivity: a translator chooses the work that has chosen them.

And while the translator’s fluency in a second language is of obvious value, their skill as a writer in their first may be of even greater worth. As Shibata has explained to me: errors in a translator’s vocabulary, a word here or a phrase there, can always be fixed. But poor writing in a translator’s native language will sink a story, a poem, an essay or a manga.

These days I pay very close attention to the translators’ names on a beloved text or attached to the subtitles of a film or anime. (Constance Garnett was my first Dostoevsky; Willa and Edwin Muir my adolescent Kafka.) Sadly, in American publishing, it’s often difficult to find those names. Japanese translations of American literature by Shibata feature the kanji of his name in larger font than the katakana of the original American authors. But in English translations of Murakami’s books, you might struggle to find the names of Rubin, Goossen, Philip Gabriel or Alfred Birnbaum.

“When you read Haruki Murakami, you’re reading me, at least ninety-five per cent of the time,” Rubin once told me in Tokyo. “Murakami wrote the names and locations, but the English words are mine.”

Can literature sometimes transcend words? One night in Brooklyn at the old BookCourt bookstore, where we were launching a new issue of MBI, I stood next to my dear friend Gabriel Brownstein, an award-winning short story writer and novelist. Hideo Furukawa was reading in Japanese his story, “Monsters,” about an apocalyptic, post-Godzilla Tokyo, his voice brittle and rangy, his body curling into a ball that popped wide open, arms flailing, with punk rock jerks and Pete Townshend windmills.

Yet before Shibata read his translation in English, Brownstein tapped my hip. “I don’t know any Japanese and didn’t get a word of that,” he said. “But I understood the whole thing.”

Editor’s note: Forget the old saw that English language readers won’t read literature in translation. For the last seven years, Monkey Business: New Writing from Japan has been publishing an annual journal of what it calls “the best of contemporary Japanese literature” in English. The paperback editions of the first three issues were completely sold out. This year, though, for reasons the editors call “both professional and personal,” it will not be releasing a new edition. Monkey Business will return with issue no. 8 in 2019 but the digital and most paperback editions of issues 1-7 are available for purchase at its online store. I asked Roland Kelts, who has been involved with the journal since its founding, to tell us about Monkey Business and his connection to Japanese literature in translation.

Eight years ago I had the good fortune of being asked to do a favor. Professors Motoyuki Shibata and Ted Goossen, esteemed literary translators, invited me to dinner in Tokyo and asked if I could help find a North American partner for their venture: an annual English-language journal of Japanese literature.

Back in New York City, my home in America, I called Brigid Hughes, founding editor of A Public Space. (Brigid had commissioned me and Shibata to assemble a portfolio on Japanese fiction for her first issue.) We had lunch in Soho, Brigid said yes, and off we went.

Our partnership has since produced seven issues of Monkey Business: New Writing from Japan (MBI). They contain stories, poems, photo essays and manga by talents internationally renowned (Yoko Ogawa, Haruki Murakami), fast rising (Hideo Furukawa, Mieko Kawakami), and those we’ll be seeing more of (Tomoka Shibasaki, Aoka Matsuda). Each issue is unpredictable and spiked with gems – what author Junot Diaz calls “an astonishment.”

In my role as MBI advisor, contributing editor and occasional road manager, the experience has been equal parts astonishment and education.

When I first read literature in translation (Dostoevsky, Kafka), the alchemy was transparent to me. I’m embarrassed to admit that as a teenager, I didn’t even know the prose had been translated, or at least I didn’t care. I just knew that the writers’ names sounded strange and cool. It felt like they were writing directly to me.

At Oberlin, poet and translator David Young taught me to think about the sound and shape of language beyond its content, which in turn made me think of its origin – not only in thought, but also in culture, place, and time. I remember learning that Ezra Pound claimed he could understand Chinese ideograms without formal study and thinking … wha?

Context is everything, and also, like a Zen koan, nothing.

After I moved to Japan and met Haruki Murakami, I asked him several questions about translation. He likened the process to living inside an author’s mind. Of J.D. Salinger’s mind, he once said while translating The Catcher in The Rye: “It’s very dark in there. That novel (Catcher) is a battle between the open world and the closed. That’s the tension. And in the end, its author chose the closed world.”

I’d never thought of the book in precisely those terms, as an internalized contest between the messiness of democratic tolerance (of the ‘phonies,’ the winners and jocks and fusty clueless schoolteachers) and the dignity and purity of authoritarian control. Through translating one of my favorite American novels, Murakami, a Japanese author, had uncovered a dark violence at its heart that I, an American reader, had never directly confronted.

Working alongside Shibata and Goossen and their team of writers and translators (Jay Rubin, Hitomi Yoshio, Michael Emmerich and David Boyd among the many) on MBI has produced similar revelations. As with the creation of it, the translation of literature is a labor of love and serious play. Matching author and translator has as much to do with sheer passion as it does with proclivity: a translator chooses the work that has chosen them.

And while the translator’s fluency in a second language is of obvious value, their skill as a writer in their first may be of even greater worth. As Shibata has explained to me: errors in a translator’s vocabulary, a word here or a phrase there, can always be fixed. But poor writing in a translator’s native language will sink a story, a poem, an essay or a manga.

These days I pay very close attention to the translators’ names on a beloved text or attached to the subtitles of a film or anime. (Constance Garnett was my first Dostoevsky; Willa and Edwin Muir my adolescent Kafka.) Sadly, in American publishing, it’s often difficult to find those names. Japanese translations of American literature by Shibata feature the kanji of his name in larger font than the katakana of the original American authors. But in English translations of Murakami’s books, you might struggle to find the names of Rubin, Goossen, Philip Gabriel or Alfred Birnbaum.

“When you read Haruki Murakami, you’re reading me, at least ninety-five per cent of the time,” Rubin once told me in Tokyo. “Murakami wrote the names and locations, but the English words are mine.”

Can literature sometimes transcend words? One night in Brooklyn at the old BookCourt bookstore, where we were launching a new issue of MBI, I stood next to my dear friend Gabriel Brownstein, an award-winning short story writer and novelist. Hideo Furukawa was reading in Japanese his story, “Monsters,” about an apocalyptic, post-Godzilla Tokyo, his voice brittle and rangy, his body curling into a ball that popped wide open, arms flailing, with punk rock jerks and Pete Townshend windmills.

Yet before Shibata read his translation in English, Brownstein tapped my hip. “I don’t know any Japanese and didn’t get a word of that,” he said. “But I understood the whole thing.”

Published on May 31, 2018 02:18

May 29, 2018

Is manga dying in Japan?

Will digital piracy ruin the future of manga?

Chigusa Ogino (photo: Toru Takeda)

Chigusa Ogino (photo: Toru Takeda)

Author and manga translator Frederik L. Schodt once pointed out to me that many of Japan’s cultural products are embraced abroad just as they are declining at home. Ukiyo-e prints became the rage in Europe in the late 19th century, nearly 100 years after they’d peaked in Edo and Kyoto. Sake sales have been climbing steadily in overseas markets, with the value of exports doubling over the past five years and hitting a record in 2017, as they continue a decades-long slide in Japan. And now: manga?

According to a survey by the Research Institute for Publications, domestic manga sales were flat last year, but the big reveal in the numbers was that digital outsold physical for the first time, rising 17.2 percent while print slipped 14.4 percent. Weekly manga magazines saw the steepest drop in sales, to below a third of what they were in 1995. A lot of digital manga content is cheap or costs nothing at all, with some of the larger, more-established apps, like messaging service Line, offering free titles to entice readers to make in-app purchases.

The North American market for manga peaked in the mid-2000s, when it breached the $200 million threshold, according to Chigusa Ogino, director at Tuttle-Mori Agency, Inc., Japan’s largest and oldest literary agency. But in 2008, the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. (known in Japan as “Lehman shock”) and the resulting financial crisis, followed a few years later by the bankruptcy of the American bookstore chain, Borders, dealt severe blows to the industry.

“A lot of publishers left the market,” Ogino says. “We saw the bottom.”

>>Read More

Chigusa Ogino (photo: Toru Takeda)

Chigusa Ogino (photo: Toru Takeda)Author and manga translator Frederik L. Schodt once pointed out to me that many of Japan’s cultural products are embraced abroad just as they are declining at home. Ukiyo-e prints became the rage in Europe in the late 19th century, nearly 100 years after they’d peaked in Edo and Kyoto. Sake sales have been climbing steadily in overseas markets, with the value of exports doubling over the past five years and hitting a record in 2017, as they continue a decades-long slide in Japan. And now: manga?

According to a survey by the Research Institute for Publications, domestic manga sales were flat last year, but the big reveal in the numbers was that digital outsold physical for the first time, rising 17.2 percent while print slipped 14.4 percent. Weekly manga magazines saw the steepest drop in sales, to below a third of what they were in 1995. A lot of digital manga content is cheap or costs nothing at all, with some of the larger, more-established apps, like messaging service Line, offering free titles to entice readers to make in-app purchases.

The North American market for manga peaked in the mid-2000s, when it breached the $200 million threshold, according to Chigusa Ogino, director at Tuttle-Mori Agency, Inc., Japan’s largest and oldest literary agency. But in 2008, the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. (known in Japan as “Lehman shock”) and the resulting financial crisis, followed a few years later by the bankruptcy of the American bookstore chain, Borders, dealt severe blows to the industry.

“A lot of publishers left the market,” Ogino says. “We saw the bottom.”

>>Read More

Published on May 29, 2018 23:57

May 23, 2018

Keynote gig, Los Angeles, July 2018

Announcing Project Anime L.A.'s Keynote Speaker Roland Kelts

Roland Kelts

Writer, scholar, editor and cultural critic Roland Kelts is the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling book, JAPANAMERICA: HOW JAPANESE POP CULTURE HAS INVADED THE U.S. His writing is published in the US, Europe, and Japan in The New Yorker, The Guardian,

The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Time Magazine, Harper's Magazine, The Japan Times and many others.He contributes commentary on Japan to CNN, the BBC, NPR and Japan's NHK, and gives talks at venues worldwide, including The World Economic Forum, TED Talks, Harvard University, the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Tokyo, the Singapore Writers Festival and anime conventions across the United States. He has interviewed several notable Japanese artists, including Hayao Miyazaki, Haruki Murakami and Yoko Ono, and is considered an authority on Japanese culture and media.

He has interviewed several notable Japanese artists, including Hayao Miyazaki, Haruki Murakami and Yoko Ono, and is considered an authority on Japanese culture and media.

Kelts has won a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship Award in Writing at Columbia University and a Nieman Fellowship in Journalism at Harvard. He is currently a visiting lecturer at Waseda University and is finishing two books, a novel and a new version of JAPANAMERICA.

He divides his time between Tokyo and New York City.

Roland Kelts

Roland KeltsWriter, scholar, editor and cultural critic Roland Kelts is the author of the critically acclaimed and bestselling book, JAPANAMERICA: HOW JAPANESE POP CULTURE HAS INVADED THE U.S. His writing is published in the US, Europe, and Japan in The New Yorker, The Guardian,

The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Time Magazine, Harper's Magazine, The Japan Times and many others.He contributes commentary on Japan to CNN, the BBC, NPR and Japan's NHK, and gives talks at venues worldwide, including The World Economic Forum, TED Talks, Harvard University, the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Tokyo, the Singapore Writers Festival and anime conventions across the United States.

He has interviewed several notable Japanese artists, including Hayao Miyazaki, Haruki Murakami and Yoko Ono, and is considered an authority on Japanese culture and media.

He has interviewed several notable Japanese artists, including Hayao Miyazaki, Haruki Murakami and Yoko Ono, and is considered an authority on Japanese culture and media. Kelts has won a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship Award in Writing at Columbia University and a Nieman Fellowship in Journalism at Harvard. He is currently a visiting lecturer at Waseda University and is finishing two books, a novel and a new version of JAPANAMERICA.

He divides his time between Tokyo and New York City.

Published on May 23, 2018 22:49

May 11, 2018

Honored to be visiting Akita, my grandmother Ebata's furu...

Honored to be visiting Akita, my grandmother Ebata's furusato (hometown), to speak at Akita International University.

Published on May 11, 2018 04:56

April 23, 2018

MANGA & MURAKAMI

Japan’s pop culture and literature drive soft power

Anime, manga and Haruki Murakami may form an unlikely trinity, but outside of Japan they’re responsible for filling Japanese Studies departments and sprawling convention halls with generations of the devoted. They’re at the core of Japan’s global allure, the center of its soft power, and last month I was immersed in all three in the span of two weeks in two countries: the United Kingdom and the United States.

In Japan, of course, they’ve all been around a while, yet they continue to draw young audiences abroad. It was 40 years ago that Murakami decided he could write a novel after watching an American baseball player hit a double for the Yakult Swallows, his favorite Japanese team. That novel, 1979’s “Hear the Wind Sing,” won Japan’s Gunzo Prize for New Writers and launched the literary career of a rarity: a bona-fide international best-selling writer who is now short-listed annually for the Nobel Prize in literature.

Twenty years ago, I met Murakami for the first time. Our one-hour interview at his Tokyo office spilled into three hours of free-form conversation that touched upon rare jazz recordings, Japanese youth culture, American individualism — and that epiphanic baseball game.

>>Read more

Anime, manga and Haruki Murakami may form an unlikely trinity, but outside of Japan they’re responsible for filling Japanese Studies departments and sprawling convention halls with generations of the devoted. They’re at the core of Japan’s global allure, the center of its soft power, and last month I was immersed in all three in the span of two weeks in two countries: the United Kingdom and the United States.

In Japan, of course, they’ve all been around a while, yet they continue to draw young audiences abroad. It was 40 years ago that Murakami decided he could write a novel after watching an American baseball player hit a double for the Yakult Swallows, his favorite Japanese team. That novel, 1979’s “Hear the Wind Sing,” won Japan’s Gunzo Prize for New Writers and launched the literary career of a rarity: a bona-fide international best-selling writer who is now short-listed annually for the Nobel Prize in literature.

Twenty years ago, I met Murakami for the first time. Our one-hour interview at his Tokyo office spilled into three hours of free-form conversation that touched upon rare jazz recordings, Japanese youth culture, American individualism — and that epiphanic baseball game.

>>Read more

Published on April 23, 2018 04:30

April 3, 2018

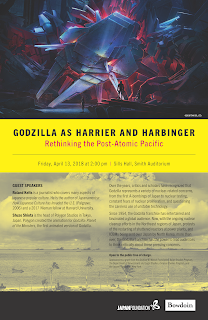

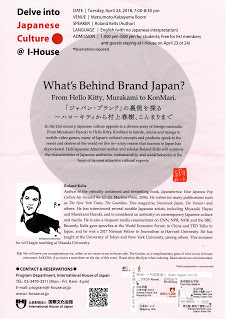

Two talks in April: Bowdoin College (Maine, US) & International House (Tokyo, JP)

Published on April 03, 2018 03:41

March 27, 2018

Hie in Ho Chi Minh (personal essay on a visit to Vietnam)

Off Assignment

When Roland Kelts was commissioned by a travel magazine to write about Vietnam, he was drawn to the vestiges of its war with the United States. But he was seduced by a man on a motorbike.

James Salter wrote that there were people we were born to talk to, and like so many of them in my memory, Hie was just there, short, squat and round-faced, a smooth-skinned twenty-something slowing down next to me as I walked. I answered his questions tersely, hoping he'd leave, but he stayed with me, turning the engine off and pushing his bike alongside: You live in Japan, ah. Oh, you're from New York. I want to go there. How can I go there?

At the hotel I asked about Hie. Mr. Lai squinted through the lobby window. "He's okay," he said.

For the next 13 days, Hie took me everywhere he thought I should go. He showed me how to slouch into the sunken nook of his vinyl bike seat and drape my arms across his belly and squeeze hard enough not to fall off, but not too hard. He took me to a smoke shop where an elderly couple at the counter handed me top value in dong for my dollars and yen and a free pack of clove cigarettes. I folded the bills into my right sock and a Ziploc bag I wedged between shirt and belt above my crotch because Hie told me to. "The thief will cut your fanny pack or back pocket with a small sharp knife." I soon trusted everything he said. (As I write this, I don't know why.)

Hie showed me how to cross the streets, none of which had traffic lights or signs. Look straight ahead, like this, he said, eyes comically wide. Don't look at drivers. If they know you see them, they keep going.

Read More>>

When Roland Kelts was commissioned by a travel magazine to write about Vietnam, he was drawn to the vestiges of its war with the United States. But he was seduced by a man on a motorbike.

James Salter wrote that there were people we were born to talk to, and like so many of them in my memory, Hie was just there, short, squat and round-faced, a smooth-skinned twenty-something slowing down next to me as I walked. I answered his questions tersely, hoping he'd leave, but he stayed with me, turning the engine off and pushing his bike alongside: You live in Japan, ah. Oh, you're from New York. I want to go there. How can I go there?

At the hotel I asked about Hie. Mr. Lai squinted through the lobby window. "He's okay," he said.

For the next 13 days, Hie took me everywhere he thought I should go. He showed me how to slouch into the sunken nook of his vinyl bike seat and drape my arms across his belly and squeeze hard enough not to fall off, but not too hard. He took me to a smoke shop where an elderly couple at the counter handed me top value in dong for my dollars and yen and a free pack of clove cigarettes. I folded the bills into my right sock and a Ziploc bag I wedged between shirt and belt above my crotch because Hie told me to. "The thief will cut your fanny pack or back pocket with a small sharp knife." I soon trusted everything he said. (As I write this, I don't know why.)

Hie showed me how to cross the streets, none of which had traffic lights or signs. Look straight ahead, like this, he said, eyes comically wide. Don't look at drivers. If they know you see them, they keep going.

Read More>>

Published on March 27, 2018 03:47