Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 57

December 9, 2021

When Are You Ready for Professional Editing?

By Lisa Poisso

Many writers equate preparing for a professional edit with revision. We���ll cover a few revision tasks in this article, but revision is only half the battle. Preparing your manuscript is the first part of getting ready for editing. The second part is preparing yourself.

Knowing when a manuscript is ready to be sent off for editing is fairly straightforward. The manuscript should be thoroughly revised, incorporating a close review of the plot, character arcs, story, and writing, outside feedback, and a healthy dose of author-powered proofreading. The manuscript you submit for editing should be the very best ambassador of your storytelling and writing abilities it can possibly be.

Knowing when you yourself are ready for editing may seem less obvious. You could choose to approach editing as a brief but unpleasant course of medicine you should hold your nose and chug as quickly as possible. Or you could choose to make more of it, as a relatively rare window allowing you to peer inside your writing in a new way. You, as a writer, are ready for editing when you���re warmed up and ready to grow.

Getting Your Manuscript Ready for Editing

A sparkling novel, like a scintillating diamond gem, is created through cutting and polishing, not simply the pressure that initially forms the stone. A first draft is still a lump of coal. It���s raw potential. A first draft has no business sticking its snoot beyond the cooling fan vents of your computer. It���s for your eyes only.

Editing a less-than-thoroughly-revised manuscript limits the book���s creative and commercial potential. It burns editorial cash and time on issues you could and should have addressed yourself. There���s no need to pay an editor to teach you fundamentals you could���ve found on websites like this one or feedback you could���ve gleaned from critique partners and early readers.

There���s a reason editors suggest revision strategies like the ones I���ve listed below: Together, they give you ample opportunity to make your work as solid as you���re capable of on your own. That���s the secret sauce in making a manuscript ready for editing.

1. Put the manuscript away for at least several weeks. You can���t revise what you can���t see, and you can���t see your own work with fresh eyes until you���ve dried out from the initial deluge of writing. Give yourself at least two weeks away from your manuscript; I recommend eight weeks or more.

2. Revise in layers like an onion, not front to back like a book. Revisions begin at the top���not at the first page of the book, but at the top layer of the manuscript. The number of drafts you generate is less important than making a dedicated revision pass for each layer: character arcs and story, plotting, individual scenes, writing depth, and proofreading. Especially if you���re new to writing, follow a systematic approach. I recommend Janice Hardy���s Revise Your Novel in 31 Days (free web articles) or the full plan in Revising Your Novel: First Draft to Finished Draft, or get Beth Hill���s encyclopedic masterpiece The Magic of Fiction (affiliate links).

3. Set a deadline. Once you���ve completed your first story-level revision draft, assign yourself a deadline for completing the rest. Story revision tends to take longer than other types, so you should reliably be able to use that to guesstimate the time needed for the rest. If you���re a sucker for some sweet external pressure, find the right editor and book your edit to give yourself a deadline with a deposit on the table.

4. Write a synopsis, even if you���ll be self-publishing. A synopsis is an unambiguous conclusive tool for proving that the plot and character arcs hang together. If you���re having trouble articulating the conflict and stakes or showing how one thing leads to the next, you have more work to do.

5. Get outside feedback. Take an initial temperature reading after your first draft with one or two trusted alpha readers. After the next draft or two, seek informed feedback from writing peers (critique groups and partners). As you get further along, test reader reactions from people you don���t personally know who actively read your genre.

6. Read the entire manuscript out loud. Hearing your book read aloud will reveal a whole host of things you overlooked during revision. Listen to the entire manuscript, noting issues as you go. Reading silently to yourself isn���t the same; you need the slower pace and different input of the hearing the text. If that much reading aloud seems overwhelming, use a text-to-speech feature or app.

By this point, you should be reaching your self-imposed revision deadline. You may notice you���ve begun endlessly fiddling with details of description or dialogue, fussing over the writing rather than structurally improving it. That���s the clarion call: time for editing.

TIP: The Storyteller’s Roadmap at One Stop for Writers has a Revision Map that gives you a good idea of what story revision can look like.

Getting Yourself Ready for Editing

Preparing yourself for editing is arguably more important than preparing your manuscript. Are you crouched in defensive mode, poised to protect your vision from outside influence, or are you ready and open to exploring new depths in your work? It���s the difference between being the naive target of other people���s visions for your work and being an informed master of your creative output.

1. Are you grounded in the craft of storytelling? What you don���t know about writing fiction can hurt you. So many new authors begin writing with the assumption that an awesome idea or scenario is all they need. Without an understanding of how the story engine works, your success will be based on instinct and luck. Level up: Learn the craft.

2. Are you a reader? Can you imagine a songwriter who listened to no music and played no instruments? Me neither. If you���ve never read the sort of book you���re trying to write, why not? If you have no idea what���s on the bestseller lists right now, why should you expect readers to buy your book? Writers write for themselves; authors write for readers. Know your readers���be one.

3. Are you expecting the editor to do the heavy lifting? If your preparation consists of whisking through your manuscript while mumbling ���I���ll let the editor fix that,��� that���s exactly what you���ll get: editing focused on fixing basics a wordsmith should already have mastered.

4. Are you ready to evolve? Your first few novels and edits are your classroom as a novelist. Are you ready for a major step in your creative evolution? Criticism can be intimidating, but turtling from feedback prevents you from growing as an artist. Editors suggest and recommend; they don���t mandate. The throttle is yours. Are you ready to accelerate?

When You���re Not Ready YetMost people assume that writing the book is the hard part. They don���t see the part of the iceberg below the waterline, the real development that takes place before and after the first draft.

Like everything else about writing, revision is a skill. You���ll get better with time and practice. If you need help at first, a story or writing coach can help you prioritize and focus your efforts.

In the end, revision may reveal fatal flaws in the manuscript, or you may decide the story has potential but your execution isn���t there yet. That���s okay; better to know that now than after you���ve paid for editing. Sometimes getting ready for editing means shelving the manuscript for now and writing another.

Onward!

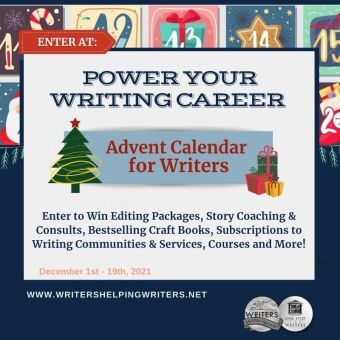

Before you go…Did you know that the Advent Calendar for Writers is on now?

Before you go…Did you know that the Advent Calendar for Writers is on now? 14 giveaways, 14 prizes to be won. Each prize is something that will help you boost your writing career and the total prize value is over $2500!

Go here to enter, and good luck!

Lisa Poisso

Lisa PoissoResident Writing Coach

Lisa Poisso’s innovative Plot Accelerator and Story Incubator coaching fast-tracks authors through story theory and development in weeks while facilitating an author-paced ���developmental edit in a bottle.��� She has decades of professional experience as an award-winning magazine editor and journalist, content writer, and corporate communications manager. She’s also a developmental and line editor, aided by an industrious team of retired greyhounds. For an extra shot of help, subscribe to her monthly Baker���s Dozen newsletter and pick up her free Manuscript Prep guide.

��

Website | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

The post When Are You Ready for Professional Editing? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

December 7, 2021

How Symbolism Adds Depth to a Story

I think we all agree, stories need to be more than a character, goal, and a series of scenarios that keep the two apart. Reading isn’t a mechanical action after all, it’s something we do to escape and enjoy. So, to deliver a true experience, we want to write fiction with layers, pulling readers in deeper as they go.

This depth can be added a number of ways���through subplots, character arc, subtext, theme, and symbolism. Of them all, symbolism is one of the simplest methods to deploy, packs a serious wallop, and is often underused. Let’s talk about why you should use it.

Symbolism can turn an ordinary object (or place, color, person, etc.) into something that goes beyond the literal. Babies represent innocence and unlimited potential, spring is synonymous with rebirth, shackles symbolize slavery, the color white brings to mind purity.

Symbols like these are considered ‘universal’ because the associated meaning is so well known within a culture or society. As such, using universal symbols in fiction means writers can deliver a deeper message without having to state it outright. Not only that, symbols tighten description too. By its very nature, if something is understood to be symbolic, it’s conveying something more.

A symbol can also be personal in nature. This is where it means something specifically to a character or specific group.

For William Wallace in the movie Braveheart, the thistle represents love since one was given to him by Murron when they were children. To most people, love in the form of a prickly weed wouldn���t typically compute. But as it���s used throughout the film at poignant moments, the audience comes to recognize this personal symbol for what it means.

So whether the symbol is universally obvious or one that���s specific to the protagonist, it can add a layer that draws readers deeper into the story. The setting itself can become a symbol as a whole should you need it to. A home could stand for safety. A river might represent a forbidden boundary.

More often than not, your symbol will be something within the setting that represents an important idea to your character. And when you look within your protagonist���s immediate world, you���re sure to find something that holds emotional value for him or her.

For instance, if your character was physically abused as a child, it might make sense for the father to be a symbol of that abuse since he was the one who perpetrated it. But the father might live thousands of miles away. The character may have little to no contact with him, which doesn���t leave many chances to symbolize. Choosing something within the protagonist���s own setting will have greater impact and offer more opportunities for conflict and tension.

Perhaps the symbol might be the smell of his father���s cologne���the same kind his roommate puts on when he���s prepping for a date, the scent of which soaks into the carpet and furniture and lingers for days.

Another choice might be an object from his setting that represents the one he was beaten with: wire hangers in the closet, a heavy dictionary on the library shelf, or the tennis racquet in his daughter���s room that she recently acquired and is using for lessons. These objects won���t be exact replicas of the ones from his past, but they���re close enough to trigger unease, bad memories, or even emotional trauma.

Symbols like these have potential because not only do they clearly remind the protagonist of a painful past event, they���re in his immediate environment, where he���s forced to encounter them frequently. In the case of the tennis racquet, an extra layer of complexity is added because the object is connected to someone he dearly loves���someone he wants to keep completely separate from any thoughts of his abuse.

Motifs: Symbolism on a Larger ScaleConnecting readers with our stories is what we all hope to achieve as authors. This is why the stories we write often contain a central message or idea���a theme���that is being conveyed through its telling. Sometimes the theme is deliberately included during the drafting stage; other times, it organically emerges during the writing process. However it occurs, the theme is often supported by certain recurring symbols that help to develop the overall message or idea throughout the course of a story. These repeated symbols are called motifs.

For example, consider the Harry Potter series. One of the motifs under-girding the theme of good vs. evil is the snake. It���s the sign for the house of Slytherin, from which so many bad wizards have emerged. Voldemort���s pet, Nagini, is a giant snake. Those who can speak Parseltongue (the language of serpents) are considered to be dark wizards. By repeatedly using this creature as a symbol for evil, Rowling creates an image that readers automatically associate with the dark side of Potter���s world.

Because motifs are pivotal in revealing your theme, it���s important to find the right ones. The setting is a natural place for these motifs to occur because it contains so many possibilities. It could be a season, an article of clothing, an animal, a weather phenomenon���it could be anything, as long as it recurs throughout the story and reinforces the overall theme.

Themes can either be planned or accidental. If you know beforehand what your theme will be, think of a location that could reinforce that idea���either through the setting itself or with objects within that place���and make sure those choices are prominently displayed throughout the story.

Need help finding the right symbol for your story?

Need help finding the right symbol for your story?Did you know we have a comprehensive Symbolism and Motifs Thesaurus at One Stop for Writers?

Stop by sometime and explore the many possible symbols that can be used to enhance the deeper themes in your writing using our FREE TRIAL.

Psst, want a crack at over $2500 in writerly prizes?

Psst, want a crack at over $2500 in writerly prizes? The Advent Calendar for Writers is on now.

14 day. 14 amazing giveaways. An astounding $2500 in prizes, each item something that will help give your writing career a boost!

The post How Symbolism Adds Depth to a Story appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

November 30, 2021

2021 Advent Calendar for Writers Giveaway Event

Your favorite holiday event is BACK!

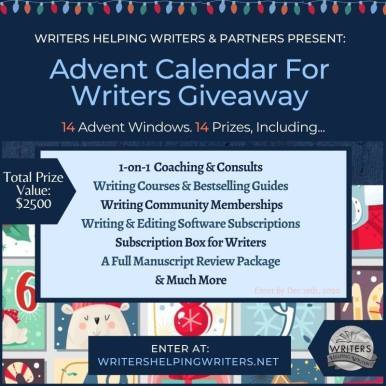

Get ready for 14 days of giveaways where you can win over $2500 in writerly prizes.

Some of the most knowledgeable and generous people in the industry have joined with us to bring you this Advent Calendar giveaway. Each prize can help you achieve your creative goals!

How it works…Advent Calendars traditionally hold a piece of holiday chocolate or a trinket, but this one is much better – it contains a host of prizes you can enter to win!

Each day between December 1-14th, 2021, a special giveaway for writers is unlocked. To discover what the prize is, click the Advent window. You might have a chance to win a subscription for writing software, a free edit, a marketing consult, story coaching, or another incredible prize.

After the last giveaway unlocks on December 14th, you have until December 19th, 2021 to enter any that you wish to. Then, watch your inbox in case you win something!

So…want to try and win something amazing?

Click this Advent Window:

Click this Advent Window: ���

To enter today’s giveaway! 14 Days.14 Amazing Giveaways. Dec 1: Something to help you power up your story structure ($200)Dec 2: Something to help you sell more books ($99) Dec 3: Something to help you gauge the strength of your book ($499) Dec 4: Something to help you polish your prose ($79) Dec 5: Something to make your story opening shine ($115) Dec 6: Something to guide you to stronger storytelling ($450)Dec 7: Something to activate your imagination & make writing easier ($90)Dec 8: Something that leads to a treasure trove of knowledge ($200)Dec 9: Something you will love when it shows up at your door ($39)Dec 10: Something to support you on the Writer’s Road ($149)Dec 11: Something to help you move toward your creative goals ($65)Dec 12: Something to help you spot problems & gain perspective ($50)Dec 13: Something to help you find your fellow creatives & get help ($65)Dec 14: Something to help you master show-don’t-tell ($50)

Check back each day to see what new prize has unlocked, and good luck!

Subject to our legal notices & rules (and those of Rafflecopter’s).

(We appreciate your social shares. Thank you!)The post 2021 Advent Calendar for Writers Giveaway Event appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

The Art (and Importance) of Specifically Ambiguous Writing

By Harrison Demchick

One of the cornerstones of effective writing is specific detail. Specific detail is what grounds the action of a scene in a tangible reality. It���s how we enable readers to see our characters and settings���and not only see them, but also hear, smell, taste, and touch them. When you���re imprecise, you���re unengaging, and that���s where you lose readers.

But what if you��want��to be ambiguous? What if that���s the whole point?

Imagine two characters in a lonely antique store at the start of a mystery. The conversation they have is meant to set up the action of the entire novel to come. Yet because this is, in fact, a mystery, you can���t reveal everything���or even much of anything. Readers aren���t supposed to know yet what the characters are talking about. Readers are meant to read on to find out.

In the case of a mystery, ambiguity is necessary. But the truth is, it’s important for all stories, because no matter the genre, we don’t want to give everything away all at once. We always want to leave a little mystery for readers to figure out. So how do we make that ambiguity compelling? How little information is too little? How much is too much?

Well, I find it���s best to imagine your story as a maze.

The MazeIt���s easy to regard a maze as the empty spaces���the corridors and passageways that bend and turn on themselves, leading you down false directions and straight into dead ends.

But what defines those empty spaces?

The trick to a maze is that it���s not about the paths. It���s about the walls. Without clearly defined walls to guide you in the right (or wrong) direction, a maze is nothing but empty, undefined space.

It���s the same when it comes to writing any story with an element of mystery: You define what readers��don���t��know, and��want��to know���in direct contrast with what they��do��know.

In other words, the walls of a good literary maze are built on bricks of specific detail. It���s just that the specific detail in question isn’t yet explained to readers.

It���s one thing to suggest that, but another to wrap your head around the concept. So let���s look at a specific example.

ProphecyOne element of writing that especially calls for this specific ambiguity is prophecy. This came up in a fantasy novel I edited earlier this year. Prophecy is by its nature uncertain and open to interpretation, but that can easily be taken for granted or taken too far. If your all-knowing sage were to suggest that with the turn of the day, the person will do the thing and the other thing will happen, it���d be a pretty lousy prophecy. Yes, it may technically be true, but it���s so vague as to be meaningless, or to be applied to virtually anything. The same is true if you drown your prophetic vision in generalized concepts like good rising to face evil or the chosen one fighting for all she holds dear.

But suppose you write that the towers will crumble where the beginning meets the end as the stars fall from the sky.

This isn���t any more intrinsically meaningful than the other examples. With no other context, it doesn���t on its own reveal itself. It���s still ambiguous. But there are specific images you can hold onto. A tower crumbling. Stars falling. Sandwiched between the images, the notion of the beginning meeting the end feels precise enough to mean something.

With this touch of specificity,��ambiguous��becomes��cryptic. We have a prophecy we can believe��will��have meaning in time. We���ve constructed the walls solidly enough for readers to start navigating the maze.

AuthenticityWhen our two characters are having their talk in the antique store, they might provide the name of a place we don���t yet know, or refer to particular events���cleaning up the blood, or dropping the bag in the Hudson River, or crashing the gala���that reveal something without revealing everything.

This is more intriguing. It���s also more authentic.

Sure, your readers aren���t supposed to know yet what���s happening���but your characters do. They know the details. It���s just the two of them. So they���re not going to couch their language in meaningless ambiguities. They need to have a real conversation���a conversation that would read every bit as real if readers��did��know everything. If your characters are being unrealistically oblique to hide information from readers they���re not supposed to know about���if it���s all about��dropping the thing in the place��and so forth���then you���re introducing a logic issue into the story.��

Think of this as��anti-exposition���characters revealing��less��than they naturally would for the benefit of the reader. Not only is it a struggle for readers to engage with writing like this, but they���re not going to believe the action on the page.

Fortifying the WallsThe benefit of using specific details doesn’t only apply to the mystery itself.

Consider the antique store. It���s not just a place: It���s the context in which our scene occurs. Taking the time to craft a very clear and particular setting provides more of that basic context readers need to navigate the maze. Readers who can see, feel, and smell the store���they’ll be more absorbed and readier to engage with what they don���t know because it falls within the context of what they do know.

Setting builds the walls.��Character��builds the walls. Who are these people in the antique store? Is there a scar on her face? A rip in his shirt? And how are they relating to one another���like long-lost friends, or close siblings, or two people meeting for the very first time?

The dialogue itself still needs detail, of course. But the more specificity we can build all around, the more precise we can be in exactly what the blank spaces in this story are���revealing to readers exactly what path they’re meant to follow.

ConclusionWe���ve focused mostly on the premise here, or the standalone scene, but all these things are important to remember as you continue to guide your readers through the maze. Let the details you reveal be concrete so as to clarify the shape of the secrets yet to be uncovered. With that constant hook of even ambiguous specificity���or especially ambiguous specificity���readers will be as compelled by what they don���t know as what they do. And that will keep them reading all the way through the end of the maze.

Developmental editor Harrison Demchick came up in the world of small press publishing, working along the way on more than eighty published novels and memoirs. He���s also the author of 2012 literary horror novel��The Listeners��and short stories including ���Tailgating��� (Tales to Terrify, 2020) and ���The Yesterday House��� (Aurealis, 2020), and as a screenwriter, his first film,��Ape Canyon,��was released in April 2021. Harrison is currently accepting new clients in fiction and memoir at the Writer���s Ally.

The post The Art (and Importance) of Specifically Ambiguous Writing appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

November 27, 2021

Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Benefactor and Recipient

Successful stories are driven by authentic and interesting characters, so it���s important to craft them carefully. But characters don���t usually exist in a vacuum; throughout the course of your story, they���ll live, work, play, and fight with other cast members. Some of those relationships are positive and supportive, pushing the protagonist to positive growth and helping them achieve their goals. Other relationships do exactly the opposite, derailing your character���s confidence and self-worth or they cause friction and conflict that leads to fallout and disruption. Many relationships hover somewhere in the middle. A balanced story will require a mix of these dynamics.

The purpose of this thesaurus is to encourage you to explore the kinds of relationships that might be good for your story and figure out what each might look like. Think about what a character needs (good and bad), and build a network of connections for him or her that will challenge them, showcase their innermost qualities, and bind readers to their relationship trials and triumphs.

Benefactor and Recipient

Description:

Sometimes, a person with ample financial resources may decide to share that excess with someone who could benefit from them. Introducing money into any relationship has the potential to create strife and alter the dynamics. And the inherent imbalance in this relationship will require both parties to progress carefully and thoughtfully if conflict is to be avoided.

Notable Examples: Great Expectations (Estella and Ms. Havisham), Indecent Proposal (Diana Murphy and John), As Good as it Gets (Melvin Udall and Carol Connelly)

Relationship Dynamics

Below are a wide range of dynamics that may accompany this relationship. Use the ideas that suit your story and work best for your characters to bring about and/or resolve the necessary conflict.

A benefactor and recipient who have a close relationship before the gifting

A relationship that grows beyond the financial arrangement and becomes personally fulfilling

A mutually beneficial arrangement that is largely transactional

A recipient becoming overly dependent on the benefactor

A benefactor whose “gift” comes with strings attached, and a recipient who feels obligated because of the gift

The gift thrusting a reluctant recipient into the limelight, leading to resentment

A recipient using the gift in a way the benefactor did not intend, causing strife

A recipient becoming entitled and expecting more resources from a benefactor who has trouble saying no

A congenial relationship becoming strained over time

Challenges That Could Threaten The Status Quo

The recipient struggling with self-doubt and a lack of confidence for being unable to care for themselves

The recipient asking for more help than the benefactor wanted to give

A third-party challenging the legality of the arrangement

The benefactor slipping into financial ruin before or after the gift is given

The benefactor becoming aware (after the fact) that the recipient lied about their difficult financial position

The recipient using the money in a way the benefactor doesn’t approve of

The recipient discovering that the money they received was “dirty”

A humble and introverted benefactor receiving unwanted attention for their actions

The recipient’s life worsening in some ways because of the gift (when fair-weather friends re-enter their life, relatives begin asking for money, the windfall causes strife in their marriage, etc.)

The recipient bragging about the gift and being targeted by thieves

Family members of the benefactor resenting their generosity

Conflicting Desires that Can Impair the Relationship

The recipient wanting more financial help than the benefactor is willing to provide

The benefactor wanting a reluctant recipient to become a surrogate son or daughter

The benefactor wanting to control or manipulate the recipient

Either party wanting to keep the charitable act a secret (while the other does not)

The benefactor wanting more gratitude than the recipient is comfortable expressing

Either party wanting a relationship beyond what the other wants

Clashing Personality Trait Combinations

Independent and Needy, Controlling and Weak-Willed, Trusting and Manipulative, Responsible and Uncooperative, Trustworthy and Dishonest, Cautious and Reckless

Negative Outcomes of Friction

Arguments and fights

Feelings of self-righteousness, entitlement, resentment, or anger

The recipient feeling a weight of debt, as if they owe something they can never repay

The parties becoming estranged

Either party having trouble setting or maintaining healthy boundaries

The recipient returning the money and continuing to suffer with financial difficulty

Tension with family members who disagree with either party’s choices

Fictional Scenarios That Could Turn These Characters into Allies

The two parties discovering a meaningful personal connection beyond finances

The recipient deciding to pass it on and help someone else in need

Both parties working together to avoid paying the taxes associated with the transaction

The benefactor taking a genuine interest in the recipient���s business venture or philanthropic cause

Either party fulfilling a relationship void for the other person

Ways This Relationship May Lead to Positive Change

A disadvantaged person accessing opportunities that might otherwise be out of reach

Either party becoming more humble, grounded, and gracious

The act of giving being so life-changing for the benefactor that they decide to do more of it

The recipient being able to leave a toxic or dangerous lifestyle because of the monetary gift

The benefactor modeling charitable acts and inspiring others

Either party considering the needs of others

The recipient sharing the financial gift with someone else in need

Themes and Symbols That Can Be Explored through This Relationship

A fall from grace, Beginnings, Deception, Depression, Family, Freedom, Friendship, Greed, Hope, Loss, Obstacles, Pride, Refuge, Suffering, Transformation, Unity, Wealth

Other Relationship Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (15 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Benefactor and Recipient appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

November 24, 2021

Gifts for Writers (That Skip the Supply Chain)

By now, you’ve probably read a few news reports about how the pandemic has disrupted the supply chain, and that it may impact shoppers this holiday season.

Those of us in the writing industry wonder if Christmas book orders will be printed and delivered in time, especially when there’s word of paper shortages and other supplies needed to create books. These worries prompted us to post our Books for Writers Gifting List at the start of November…so people wanting print copies could shop early if they wished to.

I like to be optimistic and hopeful, so my fingers are crossed we’ll weather things okay. But the “be prepared” side of Angela’s brain says maybe it would be wise to have a list of gift ideas that won’t be affected by a sluggish supply chain…just in case. So, if worry-free shopping sounds good to you, consider one of these stellar gifts:

The Hot Sheet

FACT: Jane Friedman is a publishing industry treasure. With over 20 years in publishing (including time at Writer���s Digest and the Virginia Quarterly Review), Jane knows the industry, where it’s headed, and how to help writers navigate it. In addition to being a regular speaker at publishing’s largest events and running an award-winning blog, Jane produces The Hot Sheet.

This biweekly newsletter contains all the news, trends, and market analysis a writer needs to keep up with a changing publishing industry, and would make a great gift ($59/year).

A Writing for Life Workshop

Writing is one career where there’s always more to learn, and the trick is to find the right people to learn from. C.S. Lakin is the editor of our Thesaurus Guides and her courses help a lot of writers.

If you would like to give someone the gift of knowledge, here’s her list of workshops.

A Margie Lawson Writer’s Academy Gift Certificate

If you know the name “Margie Lawson” then you’ll know why this makes my list. Margie is an incredible teacher and has a gift for showing writers how to power writing with emotion. She and her many instructors at Lawson Writer’s Academy teach on all aspects of writing craft, so the person you buy a gift certificate for will have a wealth of courses to choose from.

A Writer’s Digest Magazine Subscription

There’s something inspiring about getting a magazine every month that’s full of inspiration, success stories, new markets, and insider tips, so consider a Writer’s Digest Magazine subscription.

You can buy it in print, or digital.

The Hero’s Two Journey’s Video Set

It’s no secret Angela and Becca have a professional crush on Michael Hague. His storyteller’s brain helped then achieve a giant lightbulb moment, and so they want to see that for you, too.

One of our favorite learning tools is the Hero’s Two Journeys, a video series with Hollywood Story Experts Michael Hauge & Chris Vogler. This video collection makes a great gift ($39).

The Character Trait Bundle

Some of you might be squinting at the screen, wondering how you missed the news that there’s a digital Character Trait Thesaurus book bundle! Don’t worry, it’s understandable. This book bundle is only available through our Writers Helping Writers bookstore ($9.98).

It contains both the Positive Trait and Negative Trait Thesaurus volumes, which have been cross-linked. This means if one book mentions a trait listed in the other, you can travel right to that entry. Talk about handy when writers are brainstorming character personalities and planning friction-rich relationships!

A 1-Hour Consult with Mark Leslie

Being an author these days means we have to know a ton about things that have nothing to do with writing. Navigating different publishing platforms, price points, sales strategies, and the ‘go wide or not’ question can be overwhelming. Authors with lackluster sales can wonder if the effort is worth it. This is why an industry expert consult is on our list. Mark Leslie‘s mission is to help writers succeed (and he’s one of the nicest guys you’ll ever meet). If you know an author who is struggling, consider getting them a 1-hour consult ($99).

A Scribophile Premium Membership

Writers succeed better together, which is why being part of a community can be such a powerful boost. Creating requires a lot of mental energy, and we can doubt ourselves along the way. A Scribophile Premium Membership Gift Certificate means a writer you know can benefit from story feedback, fellowship, and the knowledge they need to help them succeed!

A Massage!

Writers spend looooong hours sitting at a desk, and this means neck pain, back pain, shoulder pain…you name it. A massage gift certificate will be well-received.

If the writer you want to send a gift to is someone you know virtually, don’t worry. Just find out what city they live in and head over to Groupon. You can choose a gift certificate for a massage or other pampering service that’s local to them (and usually save a lot in the process).

A One Stop for Writers Subscription

Crafting a fresh, engaging story is a lot of hard work, but it can be much easier with the right resources. This is where One Stop for Writers comes in. It contains an arsenal of ground-breaking tools that help writers write stronger fiction faster…and they grow their writing skills as they do it. And if a writer needs step-by-step guidance, our Storyteller’s Roadmap is a writer’s GPS for planning, writing, and revising their way to a best-selling novel.

Gift certificates range from 1-month ($9) to 6-months ($50) to a year ($90).

Tippy-tip…Thinking of getting yourself a little something? Subscribe to the 6-month plan by November 30th and get 40% off with the code BLACKFRIDAY2021. (This deal isn’t available with gift certificates, only subscriptions activated by the end date.)

I hope you find some good ideas on this list. It’s always nice to give a writing-focused gift because it shows the person we support their passion and want to see them succeed.

Finally… Happy Thanksgiving to all our America friends!We are ever grateful to have you in our lives, and we hope you have a peaceful, fulfilling day with loved ones.

Happy Thanksgiving to all our America friends!We are ever grateful to have you in our lives, and we hope you have a peaceful, fulfilling day with loved ones. The post Gifts for Writers (That Skip the Supply Chain) appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

November 23, 2021

How to Draw Readers in Through a Character���s Choices

Quick, what���s one thing you need in every scene?

This question can have a lot of answers ��� tension, conflict, stakes, emotion, action���on and on it goes. But I would argue one of the most important is one of the most basic: choice.

Characters with agency are always doing, acting, and pushing the story forward. Without action, the story stalls, which is why conflict is so important: problems, obstacles, challenges, adversaries���these things force our characters to do something to navigate past the things blocking their way. The linchpin that connects conflict to action and puts your character in the driver���s seat is choice.

Choices come in all shapes and sizes and should rarely be easy to make. Instead, they should force the character to weigh and measure, to think about possible consequences, who will be impacted, what will be lost and gained. If your character can���t see any good options at all, it comes down to what will do the least damage and to whom. Let���s look at some of the ways we can force our characters to make hard decisions.

Dilemmas: When neither choice is ideal, you have a dilemma. Decision-making will require weighing and measuring, because no matter what choice is made, there will be blood. Sometimes these choices come down to what the character is willing to sacrifice, or their preferences. Occasionally dilemmas can be between two positive choices, in which case it���s a win-win scenario.

Hobson���s Choice: This is the choice between something unwanted and an option that is even worse…kind of like expecting a raise at work but instead being given the choice of a deep pay cut or being laid off.

Sophie’s Choice: This scenario is one where the character must choose between two equally horrible options. Named for the book (and movie) Sophie���s Choice, in which the character must decide which of her two children will be killed, this is known as the impossible, tragic choice. However, it can also simply be a time-and-place decision when the character can only be in one place at that time.

Morton���s Fork: This choice is agonizing because both options lead to the same end. Die now or die later type scenarios. It���s a deceptive choice because there is only one outcome.

Moral Choices: Moral choices are those requiring the character to decide between two competing beliefs or choose whether or not to follow a moral conviction. Protect a loved one or turn him over to the police? Moral choices require the character to rationalize the decision so they can feel okay about making it.

Do Something or Nothing: In some cases, the character can choose to intervene or not get involved. These often carry a cost: a risk to their reputation (if not acting paints them as a coward), the moral repercussions of deciding to do nothing (after, say, letting someone die), or even a safety cost (if they choose to save someone who turns out to be a threat).

Make Sure Choices Carry Weight.Brainstorm possible complications that will further stress your character, increase the stakes or fallout, and create a fresh twist to your scenario. Use these challenge questions to help you:

What unforeseen consequences could happen because of this choice?Is there an unknown factor or missing piece of information that can allow me to create a reversal of the consequences and a fresh twist of fate?What sacrifice can I build into this choice that disconnects the character from a safety net that���s actually holding them back (especially when this separation is needed for the character to grow and change)?How can I tempt the character into making the wrong choice?How can I raise the stakes further?Surprise Readers With a Third Option

When it comes to wowing readers, one technique that never fails is to find the third option.

Imagine it. The walls have closed in, and your character has only two foreseeable choices. Neither is ideal, but there seems to be no other route forward.

All is lost…or so the reader thinks.

Because you–incredible story wizard that you are–have the character come up with a new, ingenious, and completely viable option so they can blaze their own trail. This third path will delight readers because it���s something they should have seen themselves but didn���t, and it upends their expectations in the best possible way.

The Firm provides a great example of this. Fresh out of law school, tax lawyer Mitch McDeere lands a too-good-to-be-true job at a law firm in Memphis. This dream job turns into a nightmare when he discovers the firm is engaging in white-collar crime for mobsters in Chicago. When he���s approached by the FBI, he���s given two choices���either continue with the corrupt law firm and eventually be thrown in jail, or work for the FBI as an informant, be disbarred, and be targeted by the mob.

The pressure is on and it seems there are no other options, but Mitch comes up with a third one: to turn over evidence for a lesser crime (mail fraud) that targets the firm instead of the Morolto crime family. This allows him to continue working as a lawyer, avoid jail, and escape the FBI���s noose.

When your character finds a third option that allows him to sidestep nasty consequences, he gets to keep his head above water and fight another day. And his ingenuity will give readers yet another thing to love about the character.

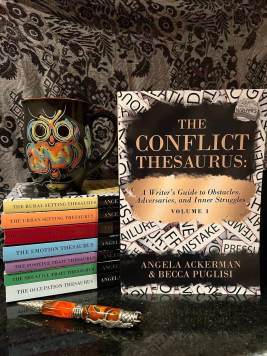

Need More Help? Add This Book to Your Reading List

Our latest guide, The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer���s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles (Volume 1) is now out and ready to help you activate your story’s conflict.

It���s packed with ideas on how to choose meaningful conflict that forces choices which will reveal your character’s inner layers to challenge your character and reveal their inner layers. It covers 120 unique conflict scenarios and ways to adapt each so you plot fresh scenes.

If you like, you can check out a sample here.

Happy writing!

The post How to Draw Readers in Through a Character���s Choices appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

November 20, 2021

Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Stepparent and Stepchild

Successful stories are driven by authentic and interesting characters, so it���s important to craft them carefully. But characters don���t usually exist in a vacuum; throughout the course of your story, they���ll live, work, play, and fight with other cast members. Some of those relationships are positive and supportive, pushing the protagonist to positive growth and helping them achieve their goals. Other relationships do exactly the opposite, derailing your character���s confidence and self-worth or they cause friction and conflict that leads to fallout and disruption. Many relationships hover somewhere in the middle. A balanced story will require a mix of these dynamics.

The purpose of this thesaurus is to encourage you to explore the kinds of relationships that might be good for your story and figure out what each might look like. Think about what a character needs (good and bad), and build a network of connections for him or her that will challenge them, showcase their innermost qualities, and bind readers to their relationship trials and triumphs.

Stepparent and Stepchild

Stepparent and StepchildDescription:

Many factors play into the dynamics of the stepparent/stepchild relationship. The child���s age and receptiveness to the stepparent will have a lot of impact. Similarly, the stepparent���s willingness to fill a parental role, their experience with children, and their relationships with the child���s biological parents can all determine how things play out. This relationship is anything but simple, making it fertile ground for plot and character development.

Relationship Dynamics

Below are a wide range of dynamics that may accompany this relationship. Use the ideas that suit your story and work best for your characters to bring about and/or resolve the necessary conflict.

A stepparent and stepchild who deeply fulfill relationship needs for each another

A stepparent who pursues harmony with the stepchild���s biological parent for the benefit of the child

A stepchild who is treated the same as the stepparent���s biological child

A stepparent filling a void for a child who has no relationship with their biological parent

A stepparent who fully embraces their role, regardless of the child���s feelings toward them

A stepparent being introduced into the life of a young adult child���smoothly, without much upheaval

A stepparent who tries to be the stepchild���s friend more than their parent

A reluctant stepparent who is playing the role of father or mother out of obligation

A stepparent whose efforts are largely controlled and limited by their spouse or the child’s other biological parent

A child rejecting any notion of a relationship with the stepparent

An apathetic stepparent who is more interested in gaining a spouse than being a mom or dad

One party struggling to accept or love the other

A stepchild actively seeking to sabotage their stepparent���s success or marriage

An estranged relationship between the two

Challenges That Could Threaten The Status Quo

The stepchild becoming injured or ill on the stepparent���s watch

The stepparent separating from or divorcing the child���s biological parent

A situation in which one of the two parties is lying, forcing the biological parent to choose who to believe

The stepparent and biological parent having a child of their own

The death of the stepchild���s biological parent

The stepparent needing to relocate for work, resulting in a major move for the child

The teenaged child rebelling against the stepparent and rejecting their authority

One of the child���s parents dealing with mental illness or addiction

The stepchild being treated differently than the stepparent’s biological children

The stepchild being diagnosed with a physical, learning, or mental health difficulty that the stepparent doesn’t understand or accept

One of the stepparent���s biological children bullying or abusing the stepchild

The stepchild discovering a harmful secret about their stepparent

The stepparent abusing the child’s biological parent

The stepparent taking a work-from-home job, resulting in them being around all the time

The stepchild preferring the stepparent over their biological parent

Conflicting Desires that Can Impair the Relationship

One party wanting a close relationship while the other does not

The stepparent wanting to legally adopt a child who doesn’t want to be adopted

Either party wanting greater control than the other party is willing to yield

The stepchild wanting their biological parents to get back together

The stepparent not wanting to be a parent

The stepparent wanting the stepchild to live full-time with the other biological parent

Both parties wanting a monopoly on the attention of the biological parent/spouse

The stepchild wanting to become emancipated

Clashing Personality Trait Combinations

Controlling and Rebellious, Independent and Needy, Nurturing and Withdrawn, Responsible and Uncooperative, Persuasive and Weak-Willed, Trusting and Manipulative, Trustworthy and Dishonest, Abrasive and Oversensitive

Negative Outcomes of Friction

One person forcing someone else to make a choice between people

Decreased trust

Feeling caught in the middle of competing interests and alliances

The stepparent and biological parent divorcing

Legal battles over custody and parental rights

Either party feeling like they can’t be completely honest or true to who they are

Anxiety and stress in the home

Arguments and fights

Domestic violence or abuse

The child pulling away from their biological parent

The child escaping a tense or unhappy home and looking for comfort in unhealthy relationships

The child running away from home

Estrangement

The child not being made a priority and experience neglect (in their education, their emotional development, etc.)

Fictional Scenarios That Could Turn These Characters into Allies

The stepparent advocating for the child���s needs

The two people standing up to an abusive or toxic third-party

The child becoming a big brother or sister to a new sibling

The child���s biological parent no longer being in the picture (through death, physical distance, abandonment, etc.), and the stepparent being able to fill the void

The stepparent helping the child reach an important goal

The two parties discovering a common interest or passion

Ways This Relationship May Lead to Positive Change

Increased trust and a widened support circle

Discovering that family can be found outside of genetic ties

Learning to embrace different views and parenting methods

The stepparent strengthening the bond between the child and their biological parent

One party learning and growing from the insight and experience of the other

Learning to put aside personal differences for the welfare of the family unit

The stepparent having the chance to do things differently with this family and not repeat the mistakes they made the first time around

Themes and Symbols That Can Be Explored through This Relationship

Alienation, Beginnings, Betrayal, Coming of age, Depression, Endings, Family, Health, Hope, Illness, Inflexibility, Innocence, Instability, Journeys, Loss, Love, Passage of time, Rebellion, Refuge, Sacrifice, Teamwork, Unity, Vulnerability

Other Relationship Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (15 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Stepparent and Stepchild appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

November 18, 2021

What���s Your Story���s Focus? Plot vs. Character Arcs

By Jami Gold

There are as many ways to tell a story as there are stories in existence. That means not all writing advice will be a good fit with the story we���re trying to tell.

An important step in knowing which advice to heed and which to ignore is being aware of the type of story we���re writing, specifically how we focus on the plot arc versus the character arc. So let���s talk about how we can discover our storytelling focus and what it means for our writing.

What Is Focus in Storytelling?���Focus��� refers to which arc���plot or character���gets more attention, has a bigger impact in our story, and/or is more closely tied to our story���s essence. Even if our story is fairly balanced, either our plot arc or our character arc is likely to have more of the focus in the story.

The focused arc might have a bigger influence on what the story feels like it���s about. Or it might involve a bigger overall change than the other arc. Or it might simply be the main thrust of the story while the other arc is more like a subplot.

Plot-Focused:

Plot-Focused:A balanced plot-focused story still includes a major character arc, but the character���s internal change doesn���t determine the direction or essence of the story as much as the plot does.

In a heavily plot-focused story, the character���s internal/emotional journey (if it exists at all) is minor and might be triggered by a subplot rather than be tied to the main plot.Character-Focused:

A balanced character-focused story still has a strong plot arc, but the essence of the story lies more in the character���s choices with those events and dilemmas.

In a heavily character-focused story, plot events might exist just enough to help reveal the character���s issues and/or force them to change.How Can We Tell Which Arc Has Focus in Our Story?

Obviously, we might be able to tell what type of story we have just by being in tune with our writing. But if we���re not sure���especially if our story is more balanced between the arcs���or if we want to verify that our draft matches our goals for the story, we can ask ourselves:

When thinking about what made us want to write our story, do we think more about the cool plot events���or about our character���s emotional struggle?When describing our story to others, do we talk about what happens���or how events affect our character?Most importantly, which could we change more easily without affecting the essence of our story: our character���s choices and growth���or the plot events that cause our character���s struggle?If we chose the first answer for each question above, our story is probably plot focused. But if we chose the second answer in each, our story is more likely to be character focused.

For example, if���

our original inspiration was to write a story about a character overcoming addiction, andwe describe our story through the lens of how they struggle with addiction, andwe could easily change the plot details of their addiction (how they got hooked, the obstacles they face, etc.) without changing the essence of their struggle���

our original inspiration was to write a story about a character overcoming addiction, andwe describe our story through the lens of how they struggle with addiction, andwe could easily change the plot details of their addiction (how they got hooked, the obstacles they face, etc.) without changing the essence of their struggle������then we probably intend to write a character-focused story. And once we know our answers, we should keep that intention in mind through our drafting, editing, and publication process.

Note, however, that if our answer to the third question doesn���t match the first two, our story draft may not be matching our intentions (unless our story is strongly balanced, in which case, that question can be difficult to answer). In case of a mismatch, though, we might need to step back and reanalyze our approach to the story.

How Can This Understanding Help Us?In addition to being able to judge how well our story matches our intentions, knowing the focus can help us recognize when advice won���t apply to our story. If we have a plot-focused story, all the tip-filled blog posts and feedback suggestions about character arcs might not be helpful to us and might even make us question our writing skills.

On the other hand, if we have a character-focused story, all the advice about including a strong villain or antagonist plot might make us worry our story will be boring. In other words, we should give ourselves permission to ignore the advice that doesn���t apply to our style���unless we decide it works for the story we���re trying to tell.

Also, understanding the focus can help us approach our marketing for the story (including query or back-cover blurb). If we have a character-focused story, our book���s description might only need to include just enough plot detail to clarify the character���s struggles.

Or if we have a plot-focused story, we���d know not to spend many words on the character���s internal issues. Instead, we might just label their internal perspective in their character ���tag��� (cranky detective, hopeful student, etc.).

Of course, we can���t always control others��� expectations, so using the right marketing focus isn���t a guarantee to avoid reader disappointment. (Check out my companion post to this one on how the new Dune movie by Denis Villeneuve is an interesting example of a character-focused story that was expected by some to be more plot focused.) In most cases, however, our marketing is the best way to lead reader expectations in the direction we want.

Our story is unique, and we don���t want to feel pressured to follow guidance that doesn���t fit the story we���re trying to tell. With the right understanding of our story, we���ll know when to listen to others��� advice and when to listen to our own instincts. *smile* Do you have any questions or insights about storytelling focus and how a better understanding could help our writing (and publishing) process?

Jami Gold

Jami GoldResident Writing Coach

After muttering writing advice in tongues, Jami decided to put her talent for making up stuff to good use. Fueled by chocolate, she creates writing resources and writes award-winning paranormal romance stories where normal need not apply. Just ask her family���and zombie cat.

Website | Goodreads | Twitter �� Facebook �� Pinterest

The post What���s Your Story���s Focus? Plot vs. Character Arcs appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

November 16, 2021

How to Show Emotion for Non-Viewpoint Characters

Those of you who are familiar with me know that Angela Ackerman and I talk a lot about emotion. A LOT.

That���s because we believe that clearly conveying emotion���particularly that of the protagonist or viewpoint character���plays an important role in building reader empathy. If we can build a strong connection for the reader, they���ll become invested in the character and be more likely to keep reading.

The other reason character emotion is so important is that it draws the reader into the story. If we���re able to show emotion well, we heighten the reader���s experience; instead of them sitting back and being told about the character���s emotions, they���re feeling them as the story goes along. They���re invited to share in the journey.

That level of engagement is critical if we���re going to pull readers into our stories and keep them there.

Quick Recap: How to Show a Viewpoint Character’s EmotionHere���s an example of character emotion that has been��shown, taken from the��2nd Edition of the Emotion Thesaurus:

JoAnne sat on the chair���s edge, spine straight as a new pencil, and stared into Mr. Paxton���s face. Sixteen years she���d given him���days she was sick, days the kids were sick���making the trip back and forth across town on that sweaty bus. Now he wouldn���t even look at her, just kept fiddling with her folder and pushing around the fancy knickknacks on his desk. Maybe he didn���t want to give her the news, but she wasn���t gonna make it easy for him.

Mr. Paxton cleared his throat for the hundredth time. The vinyl of JoAnne���s purse crackled and she lightened her grip on it. Her picture of the kids was in there and she didn���t want it creased.

���JoAnne���Mrs. Benson���it appears that your position with the company is no longer������

JoAnne jerked to her feet, sending her chair flying over the tile. It hit the wall with a satisfying bang as she stormed out of the office.

Through a combination of body language, thoughts, and reactions, we can see what JoAnne is feeling without her ever stating it outright. And because we���ve also learned something about who she is and where she���s coming from, our empathy is piqued. So��showing emotion for our��protagonist��pays off��in spades.

But How Do I Show Emotions for Other Characters?That example may not be news to you, since the importance of showing emotion has been discussed quite a bit. What hasn���t been talked much about is how to convey the feelings of a non-viewpoint character (NVPC).

Unless you���re writing in omniscient viewpoint, you���ll need to stick closely to your main character���s point of view and won���t be able to share what���s happening internally for anyone else. So��how do you convey the emotions of the other people in your story?

Technique #1: Outer Manifestations

When you���re in the main character���s head, you can���t access the thoughts and internal sensations of other cast members to show what they���re feeling. But you can use the outer manifestations of their emotions because the viewpoint character will be able to notice those.

In the example above, we can tell that Mr. Paxton is uncomfortable, maybe even nervous, about giving JoAnne the news. We know this because of what the viewpoint character is able to observe: the fiddling with knickknacks and his frequent clearing of the throat.

When we���re revealing the emotion of a NVPC, we can���t utilize all the same techniques that we could for the protagonist, but we can use the ones that are noticeable by others, such as:

body languagefacial expressionsvocal shiftschanges in posture and personal spaceTechnique #2: The Viewpoint Character���s ResponseMr. Paxton���s fussing and throat clearing aren���t enough to show exactly what he���s feeling because they could represent numerous things, such as restlessness, excitement, or nervousness. But JoAnne���s response to these clues clarifies his state.

Through her thoughts, we learn that her boss is reluctant to give her the news; that information provides some much-needed context to help us understand what Mr. Paxton is feeling.��Thoughts��can work well to show the viewpoint character���s response; so can��body language��and the��decisions��they make during or following an interaction.

Technique #3: Dialogue and Vocal CuesWhen we���re feeling emotional, one of the ways it comes through is in our speech patterns. Sometimes this can be shown through��vocal cues��(changes in pitch, tone, speed of speech, word usage, etc.), such as Mr. Paxton���s hesitations.

It can also be shown through the��words themselves���say, if a character is ranting about the events leading up to his current emotional state.��The reader will be able to combine this verbal context with the nonverbal body language��to figure out what emotion is being felt.

Technique #4: AvoidancesIf a NVPC���s emotions are uncomfortable ones, this can lead them to avoid certain things associated with them: a person, a place, a situation, specific questions, or a topic of conversation.

One of the clues to Mr. Paxton���s emotional state is his procrastination���how he���s putting off the difficult job of letting JoAnne go. She���s been sitting there a while, long enough to get pretty worked up as she watches him dither. His avoidance of the conversation itself shows a high level of discomfort, putting his emotional state into perspective for the reader.

Technique #5: Fight, Flight, or Freeze Reactions

When a character feels threatened, certain emotions will come into play. In these situations, a character may get confrontational, beat a hasty exit, or turn into the proverbial deer in the headlights.

Just as real-life people have a��fight, flight, or freeze response��to threatening scenarios, characters should, too. If you know which way your character leans, you can write their reactions in a way that readers (who are familiar with these responses) will be able to identify the emotion at work.

Technique #6: Changes to the Character���s BaselineOne vital part of writing emotion well is doing some research beforehand to figure out your character���s emotional range. This enables you to write him or her consistently throughout the story.

Then, when something happens that impacts their emotions, they���ll deviate from that norm, and readers will notice the shift. Changes in the voice, speech patterns, body language, how the character interacts with or responds to others, new avoidances���anything that alters their typical behavior can become a red flag for readers, letting them know that emotions are in flux.

As you can see, you have a lot of resources when it comes to writing the emotions of non-viewpoint characters. Some of them can work in isolation, but many of them should be used in tandem to help clarify things for the reader.

Use some visible body language while also noting the viewpoint character���s response to it. Show the character���s avoidance along with a persistent vocal cue to make the emotion clear. Use a flight response to a seemingly unthreatening situation along with a bit of dialogue to shed some light on what���s happening.

With a combination of these techniques, you���ll be able to paint a complete picture��of any non-viewpoint character���s emotions without hopping heads and pulling readers out of the story.

For more information on showing character emotion effectively, check out the 2nd edition of The Emotion Thesaurus and this list of resources.The post How to Show Emotion for Non-Viewpoint Characters appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1014 followers