The Art (and Importance) of Specifically Ambiguous Writing

By Harrison Demchick

One of the cornerstones of effective writing is specific detail. Specific detail is what grounds the action of a scene in a tangible reality. It���s how we enable readers to see our characters and settings���and not only see them, but also hear, smell, taste, and touch them. When you���re imprecise, you���re unengaging, and that���s where you lose readers.

But what if you��want��to be ambiguous? What if that���s the whole point?

Imagine two characters in a lonely antique store at the start of a mystery. The conversation they have is meant to set up the action of the entire novel to come. Yet because this is, in fact, a mystery, you can���t reveal everything���or even much of anything. Readers aren���t supposed to know yet what the characters are talking about. Readers are meant to read on to find out.

In the case of a mystery, ambiguity is necessary. But the truth is, it’s important for all stories, because no matter the genre, we don’t want to give everything away all at once. We always want to leave a little mystery for readers to figure out. So how do we make that ambiguity compelling? How little information is too little? How much is too much?

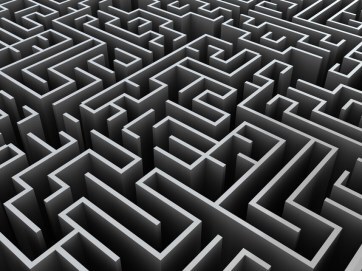

Well, I find it���s best to imagine your story as a maze.

The MazeIt���s easy to regard a maze as the empty spaces���the corridors and passageways that bend and turn on themselves, leading you down false directions and straight into dead ends.

But what defines those empty spaces?

The trick to a maze is that it���s not about the paths. It���s about the walls. Without clearly defined walls to guide you in the right (or wrong) direction, a maze is nothing but empty, undefined space.

It���s the same when it comes to writing any story with an element of mystery: You define what readers��don���t��know, and��want��to know���in direct contrast with what they��do��know.

In other words, the walls of a good literary maze are built on bricks of specific detail. It���s just that the specific detail in question isn’t yet explained to readers.

It���s one thing to suggest that, but another to wrap your head around the concept. So let���s look at a specific example.

ProphecyOne element of writing that especially calls for this specific ambiguity is prophecy. This came up in a fantasy novel I edited earlier this year. Prophecy is by its nature uncertain and open to interpretation, but that can easily be taken for granted or taken too far. If your all-knowing sage were to suggest that with the turn of the day, the person will do the thing and the other thing will happen, it���d be a pretty lousy prophecy. Yes, it may technically be true, but it���s so vague as to be meaningless, or to be applied to virtually anything. The same is true if you drown your prophetic vision in generalized concepts like good rising to face evil or the chosen one fighting for all she holds dear.

But suppose you write that the towers will crumble where the beginning meets the end as the stars fall from the sky.

This isn���t any more intrinsically meaningful than the other examples. With no other context, it doesn���t on its own reveal itself. It���s still ambiguous. But there are specific images you can hold onto. A tower crumbling. Stars falling. Sandwiched between the images, the notion of the beginning meeting the end feels precise enough to mean something.

With this touch of specificity,��ambiguous��becomes��cryptic. We have a prophecy we can believe��will��have meaning in time. We���ve constructed the walls solidly enough for readers to start navigating the maze.

AuthenticityWhen our two characters are having their talk in the antique store, they might provide the name of a place we don���t yet know, or refer to particular events���cleaning up the blood, or dropping the bag in the Hudson River, or crashing the gala���that reveal something without revealing everything.

This is more intriguing. It���s also more authentic.

Sure, your readers aren���t supposed to know yet what���s happening���but your characters do. They know the details. It���s just the two of them. So they���re not going to couch their language in meaningless ambiguities. They need to have a real conversation���a conversation that would read every bit as real if readers��did��know everything. If your characters are being unrealistically oblique to hide information from readers they���re not supposed to know about���if it���s all about��dropping the thing in the place��and so forth���then you���re introducing a logic issue into the story.��

Think of this as��anti-exposition���characters revealing��less��than they naturally would for the benefit of the reader. Not only is it a struggle for readers to engage with writing like this, but they���re not going to believe the action on the page.

Fortifying the WallsThe benefit of using specific details doesn’t only apply to the mystery itself.

Consider the antique store. It���s not just a place: It���s the context in which our scene occurs. Taking the time to craft a very clear and particular setting provides more of that basic context readers need to navigate the maze. Readers who can see, feel, and smell the store���they’ll be more absorbed and readier to engage with what they don���t know because it falls within the context of what they do know.

Setting builds the walls.��Character��builds the walls. Who are these people in the antique store? Is there a scar on her face? A rip in his shirt? And how are they relating to one another���like long-lost friends, or close siblings, or two people meeting for the very first time?

The dialogue itself still needs detail, of course. But the more specificity we can build all around, the more precise we can be in exactly what the blank spaces in this story are���revealing to readers exactly what path they’re meant to follow.

ConclusionWe���ve focused mostly on the premise here, or the standalone scene, but all these things are important to remember as you continue to guide your readers through the maze. Let the details you reveal be concrete so as to clarify the shape of the secrets yet to be uncovered. With that constant hook of even ambiguous specificity���or especially ambiguous specificity���readers will be as compelled by what they don���t know as what they do. And that will keep them reading all the way through the end of the maze.

Developmental editor Harrison Demchick came up in the world of small press publishing, working along the way on more than eighty published novels and memoirs. He���s also the author of 2012 literary horror novel��The Listeners��and short stories including ���Tailgating��� (Tales to Terrify, 2020) and ���The Yesterday House��� (Aurealis, 2020), and as a screenwriter, his first film,��Ape Canyon,��was released in April 2021. Harrison is currently accepting new clients in fiction and memoir at the Writer���s Ally.

The post The Art (and Importance) of Specifically Ambiguous Writing appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1014 followers