Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 2

October 31, 2025

Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Altruism

When a character suffers emotional pain, the brain���s response is to stop the discomfort, and often this results in a coping mechanism being deployed. Whether it’s an automatic response or a learned go-to strategy, a mechanism helps them cope with the stress of the moment or escape the hurt of it.

But if the character develops an unhealthy reliance on that mechanism, problems will arise. Long-term, certain coping behaviors will impair their connections with others, their ability to achieve goals and dreams, and their ability to handle life’s pressures.

At some point, they must have an Aha! moment where they realize their coping method is holding them back and seek other ways to deal with stress. Namely, they���ll have to adopt healthier mechanisms that enable them to manage difficulties and ultimately have a happier future.

To help you write your character’s growth (or regression) journey, we’ve created The Coping Mechanism Thesaurus, which contains a range of coping mechanisms. The one we’re highlighting today can help your character better manage painful emotions and stress. Use this partial entry to show readers the character is choosing more productive strategies that will build resilience.

Altruism DefinitionBeing concerned for the welfare of others and selflessly acting to help��

What It May Look LikeStepping in to help, unasked (grabbing the door for someone carrying a burden, picking up an item someone dropped and returning it, acting quickly to catch a dog that slipped their owner���s leash)

Giving time to causes

Running errands for those who need help

Donating items to a charity shop or organization

Random acts of kindness

Wanting to help but not knowing how

Feeling guilt at ‘benefiting’ (say, experiencing a rush of wellbeing due to the act, or it resulting in reciprocity or a reward)

Clashing responsibilities (e.g., wanting to donate but the family���s rent is due)

Having good intentions but accidentally making things worse

Being disappointed if a kindness isn’t acknowledged or appreciated

Wanting to help but not feeling qualified

Being considerate by default, but not wanting to reward someone���s bad behavior

Wanting to help but having a time constraint

Something coming up that requires the character to walk back their offer to help

Wanting to restrict help or support because that person is acting entitled to it

Esteem and Recognition: Practicing altruism can allow a character to make amends. For example, a convicted impaired driver could speak at high schools, sharing their story and the deadly cost of mistakes.

Love and Connection: When there���s friction between people, altruism can be the olive branch that helps the relationship heal.

Safety and Security: Providing help after a natural disaster could make a character feel that wider stability is being restored, improving their own sense of security.��

Need More Descriptive Help?

While this thesaurus is still being developed and expanded, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Altruism appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 29, 2025

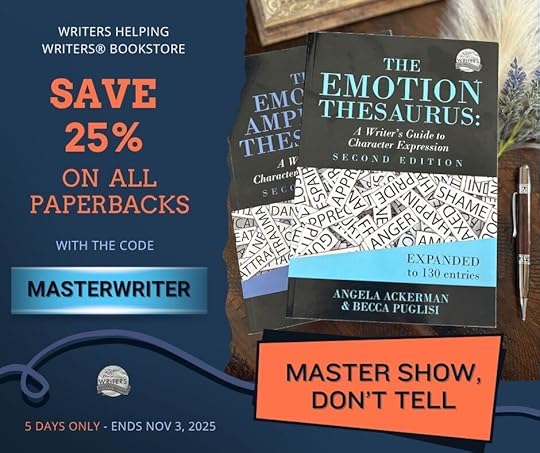

Save 25% on Writers Helping Writers Thesaurus Books

Earlier this year, we launched the Writers Helping Writers�� bookstore so writers could find our books in the formats they need, all in one place.

We started by adding eBook and PDF formats to the store, with plans for the paperbacks to follow. Well, friends–that day is finally here, and we are celebrating with a 25% discount code for print books when you purchase them from our store!

(This is a crazy-good deal, one that we may not be able to do again.)

Putting a store and supply chain for books together is a lot of work, and so it’s nice to celebrate our step of independence away from the big monopoly book retailers. With Christmas just around the corner, we hope this sale is a good time to buy a gift for a writer you know, and maybe pick up a little something for yourself!

Our Books Help You WriteDeeper, More Powerful Stories

Each writing guide in our series dives into an important area of description and shows you how to activate it to create stand-out characters and immersive fiction. Not only do you learn how to apply show, don’t tell in ways you’ve not thought of, but you’ll also discover new ways to connect readers to your characters and make them feel part of the story!

5 Days to Save 25%!If you need help taking your stories to the next level, or you’ve heard about these thesaurus guides and always wondered what the fuss was about, swing by our store and poke around. You can find all our print volumes here.

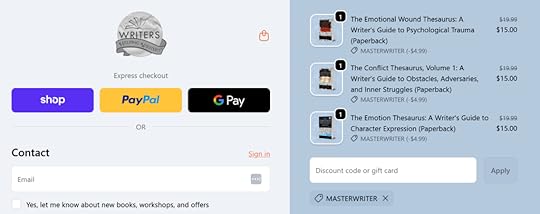

Once you’re at the checkout, use the code MASTERWRITER in the box provided and your discount will display onscreen.

How much will I pay for shipping?

How much will I pay for shipping?It depends on your location, but don’t worry���it will be calculated at checkout, so you see the full price before finalizing your purchase. Note: if you’re typically charged duty or other fees on products shipped from outside your country, those may also be charged upon delivery.

When will my paperback order arrive?

Orders are printed and shipped by one of Bookvault’s four global fulfillment centers. Delivery time will vary depending on where the book is printed and where it���s going. Based on past orders, we can estimate 12-15 days for deliveries within the US and Canada. Elsewhere, it may be longer, closer to 14-21 days. Ordering now puts you in the safe zone for Christmas!

Can I track my order?Yes! When your order is sent out, you���ll receive a shipping confirmation email that contains tracking information. If you don���t get this email or it doesn���t have a tracking number, please contact us directly.

And while print is sort of the prom queen of this post, if you prefer a portable option that goes where you do, we have eBooks and PDFs, too.

A small favor…

A small favor…Reviews are the lifeblood of any business. If you’ve purchased a book from us, would you consider leaving a review?

If it’s easier, you can scan this QR code, too. Thank you so much for taking the time to review our books!

The last day to save 25% on print books is November 3rd, 2025. Happy writing!

The post Save 25% on Writers Helping Writers Thesaurus Books appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 28, 2025

What Really Keeps An ADHD Writer Coming Back to the Desk? Hint- It’s Not Routine

Discover productivity tips from editor and coach Kirsten Donaghey who specializes in helping writers, creatives and ADHDers with projects and daily life. Check out two amazing prizes you can win at the bottom of this post.

As an ADHD Coach who works with a lot of writers, one of the most common questions I get from clients is: How can I be consistent with my writing?

I have been there myself, trying to trick my brain into showing up on a regular basis for my writing. Schedules, pep talks, forcing myself to sit at my desk even if I didn’t write a word. I spent so much energy trying, only to feel like a failure when I drifted away from yet another project.

I genuinely wanted to write. I often told people that writing was the way I processed the world around me. It was my filter from the chaos. It was a need as much as a desire.

So let me share with you what I’ve learned from my own experience, as well as from working with hundreds of writers who have struggled with this. We have been barking up the wrong tree. The question isn’t how to force consistency. If we are honest, we know better; if it feels forced, it’s not going to work long term. The real question is: what makes you hungry to write?

Trust Your Brain to Do What It Does Best

There’s a momentum that happens when you’re deep in a piece of writing. Your ADHD brain, usually bouncing from one thought to another, is in a state of flow, or hyperfocus. The constraints of time disappear. The world (aka distractions) beyond your document ceases to exist. This isn���t the result of discipline or consistency���this is you being authentically creative. The ADHD brain is naturally creative ��� thoughts travel away from the point, in all directions, to explore. But if you trust your brain, you will know that it is out there making connections. Ideas that seem random link up and produce new ideas. This process gives us that amazing dopamine surge.

I see it in my clients’ faces when they describe their best writing days. Their eyes light up, they become animated. They’re not talking about grinding through word counts or following schedules. They’re talking about sliding into something that felt authentic.

Allowing yourself space and patience for this to happen is what counts. When you are hyper-aware of word counts and doing it right, your ADHD brain will create resistance. The goal is not to fight resistance; it’s to let go of expectations so your creative brain has room to do what it does best.

Beyond the Productivity TrapHere’s where most writing advice fails ADHD brains: it gives advice and one-size-fits-all strategies, saying things like, just get your butt in the chair and write, or put it into your schedule. But we don’t like instructions or rules. We’re meaning-makers, pattern-seekers, connection-builders. The ADHD writers who finish their drafts aren’t the ones who’ve mastered discipline���they’re the ones who’ve learned to recognize and trust their own patterns of engagement.

They know that Tuesday mornings feel electric while Mondays are almost always a struggle. They’ve noticed that handwriting unlocks something that typing doesn’t. They’ve stopped fighting their need for background noise or complete silence or seven different colored pens.

So, ask yourself:

What do I need? How do I want to show up as a writer? What makes writing enticing? What makes me feel authentic?

And then ask yourself:

Why do I avoid my writing? (Do you hate your desk? Do you not believe in your story? Are you afraid you aren’t good enough?) Where do I feel stuck?

And finally:

If there was one thing I could change that would make me hungry to write, what would it be?

If you are having trouble staying with your writing project, I would suggest trying this first. Block off an hour or two of protected, uninterrupted time. Make sure you do it at a time when you’re not tired or distracted. Lie on the floor or go for a walk. Do something that relaxes you. Now, really delve into what is coming between you and your creative energy. Because whatever it is, it is a barrier. Not to be conquered, to be known, so you can gracefully step around it, saying, I���m not here to fight, I���m here to write.

The Practice of NoticingStart here: choose not to worry about word counts or daily goals. Instead, become a detective of your own desire. Notice what pulls you toward your writing and what pushes you away. Take notes if you feel like. Breathe it in. Own it.

Notice the difference between wanting to write and needing to write. The want is pleasant but negotiable. The need is urgent, almost uncomfortable���like hunger or the pressure of held breath. The need is what brings you back.

Notice the moments when your story feels most alive to you. Is it when you’re walking? In the shower? Right before sleep? These aren’t distractions from your “real” writing time���they’re glimpses of your story’s natural rhythm.

Notice what happens in your body when you think about your unfinished draft. Does your chest tighten with anxiety or expand with anticipation? Your body is giving you information about what your story needs from you.

The Violence of “Must” and “Should”And finally, we need to talk about the language that’s been poisoning our relationship with our own creativity. Listen to how we talk about writing: I must establish a routine, I should write every day, I need to manage my time better.

Every single one of these phrases is a creativity killer for the ADHD brain.

When we frame writing as something to be managed, we transform it from play into work. When we insist it requires a routine, we strip away the spontaneity that feeds our inspiration.

ADHD writers often learn to hate the act of writing because the route there makes them feel bad. It���s not a straight line back to your desk. It���s not a matter of trying harder, planning better, or engaging in processes that feel like punishment. It���s an exploratory route of reflecting and playing, to better understand how to be our authentic, creative selves.

You can explore your ADHD and discover how it affects your writing practice, gain some insight, and learn some effective strategies in my new book (co-authored with Nicole Bross) ����� A Novel Approach: Strategies for ADHD Writers

Kirsten generously has two giveaways!One lucky winner will receive a copy of her new co-authored book, A Novel Approach: Strategies for ADHD Writers.

Full of exercises, case studies, and thought-provoking advice, A Novel Approach will give you the tools you need to develop new habits and practices that work with, not against your ADHD. Your ADHD doesn���t have to stand in the way of your dream of being an author. It���s time to rewrite the story you���ve been telling yourself about what you can do, because your ADHD doesn���t get the final word���you do.

One lucky winner will receive a 45 minute coaching session.Many ADHD writers benefit from 1:1 coaching to help them better understand how their specific ADHD challenges are getting in the way of finishing their book. In coaching, we not only identify roadblocks but also focus on harnessing your strengths to create a writing practice that works for you.

Enter one or both of these giveaways HERE.Please thank Kirsten for her generosity in the comments. Winners will be announced on this post and notified via e-mail on Monday, November 3. Good luck.

Book Structure for Disorganized Writers

Writing Tips from a Neurodivergent Brain

Amazing Resources for Neurodivergent Writers

Kirsten Donaghey is the author of A Novel Approach – Strategies for ADHD Writers. She is a certified ADHD coach and longtime editor and writing coach. A Canadian living in Vienna, she was the founder of a nonprofit writing hub where she organized writing workshops and networking events for local writers. She now works with clients worldwide as a coach and editor, thriving on collaboration and creative solutions. Her own inspiration comes from reading, traveling, hiking, meaningful exchanges, and creating. She specializes in helping writers, creatives, academics, and ADHDers with their projects and daily life.

The post What Really Keeps An ADHD Writer Coming Back to the Desk? Hint- It’s Not Routine appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 24, 2025

Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Denial

When a character suffers emotional pain, the brain���s response is to stop the discomfort, and often this results in a coping mechanism being deployed. Whether it’s an automatic response or a learned go-to strategy, a mechanism helps them cope with the stress of the moment or escape the hurt of it.

But if the character develops an unhealthy reliance on that mechanism, problems will arise. Long-term, certain coping behaviors will impair their connections with others, their ability to achieve goals and dreams, and their resiliency in handling life’s pressures.

At some point, they must have an Aha! moment where they realize their coping method is holding them back and they need to seek other ways to deal with stress. Namely, they���ll have to adopt healthier mechanisms that enable them to manage difficulties and ultimately have a happier future.

To help you write your character’s growth (or regression) journey, we’ve created The Coping Mechanism Thesaurus, which contains a range of coping methods. The one we’re highlighting today can be damaging, and we hope this partial entry will help you show your character’s struggle in a way readers can relate to.

DenialDefinitionRefusing to accept facts or reality to avoid painful truths. This can apply to past events or current truths that are unpleasant, upsetting, or frightening.

What It May Look LikeCreating a fantasy version of unpleasant memories, and believing this is how they happened

Becoming agitated or angry when certain subjects are brought up

Avoiding people who continue to bring up the truth

Rationalizing unhealthy behavior (their own or someone else���s), thereby denying a problem exists

Blaming others, so the character can pretend there isn���t an internal issue to address

Love and Connection: Refusing to manage their problem or face the truth can create friction in important relationships. The character���s denial may even cause them to push away people who speak the truth.

Safety and Security: Denial of physical problems will only make them worsen, and not accepting a known truth can create mental health issues that can impair the character���s health.

Feeling powerless, as if they���re incapable of dealing with the problem

A relationship falling apart because the character fails to acknowledge how they���re contributing to its failure

A physical or mental condition worsening when the character refuses to seek treatment

Experiencing a crisis due to fallout from ignoring a personal problem (getting fired, beating someone up, etc.)

Medical problems from high cortisol produced by long-term stress

Replacing negative coping mechanisms with positive ones is how your character turns the page, but it starts with internal work, new habits, and practices:

Recognizing that their response isn���t healthy, and wanting to change

Listening to the internal voice trying to tell them the truth or that the way they���re remembering events isn���t quite right

Engaging a therapist to help them cope

Need More Descriptive Help?

While this thesaurus is still being developed and expanded, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Denial appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 22, 2025

Writing 101: Popular Structure Models that Work

Every successful story, no matter the genre or format, has some structure at its core. It���s the backbone that provides shape and purpose. Without it, even the most compelling ideas can lose focus and wander off track, making it harder for readers to engage.

Whether you’re a dedicated plotter or a discovery writer who prefers to see where the story goes, structure still plays a role. You don���t have to outline every scene and know everything that will happen; just figuring out the key turning points can help you shape a satisfying beginning, middle, and end (and avoid the dreaded saggy middle).

There are many proven structure systems out there, and each offers a slightly different lens to help writers frame their stories. Here are five widely used and respected models.

(affiliate links ahead)

Save the CatOriginally created for screenwriters, Blake Snyder���s Save the Cat has become a tried-and-true structure for novelists. It focuses on 15 ���beats��� that can be used to map your story’s emotional and narrative progress.

Why It WorksThe beats are clear, simple, and easy to followIt indicates where in the story beats should occur, so the pace doesn���t flagYou can use it while planning, drafting, or revisingBONUS TIP: Save the Cat! Writes a Novel (Brody) is an adaptation of Snyder���s screenwriting model for novels.

The Snowflake MethodWith Randy Ingermanson���s model, you start small (with a one-sentence summary) and build bigger, gradually expanding that nugget into character profiles, plot points, and whole scenes.

Why It WorksIt���s great for writers who like to start with a concept and expand logicallyThe complexity builds little by little, so you don���t get overwhelmedIt���s especially helpful if you���re working on a high-concept storyBecause of its unique approach, the Snowflake Method works well for analytical thinkers and writers who like structure but want flexibility.

The Writer���s JourneyChristopher Vogler���s The Writer���s Journey adapts Joseph Campbell���s The Hero���s Journey into a user-friendly guide for storytellers. Focused on character arc, this model follows a character through familiar stages, such as The Ordinary World, The Call to Adventure, Crossing the First Threshold, and Return With the Elixir.

Why It WorksIts patterns resonate with the human psycheIt focuses heavily on transformation and character arcPlot and theme are blended in a way that elevates bothBONUS: Vogler���s book also examines common character archetypes (the hero, mentor, shadow, etc.) and how to make the most of them in your story.

Michael Hauge���s 6-Stage Plot StructureMichael Hauge, a well-known Hollywood story consultant, created the 6-Stage Plot Structure for mapping a character���s inner journey alongside plot developments. It breaks the story into six stages and five turning points that can easily be used to map your story.

Why It WorksIt pairs internal transformation with external plotIt focuses on creating an emotional payoff, not just an exciting storyIt charts a protagonist���s evolution from identity (who they pretend to be) to essence (who they truly are)PSST: This is Becca and Angela���s preferred structure model. We like it so much that we used it to create a Story Map tool at One Stop for Writers. Check it out!

K.M. Weiland���s Structuring Your NovelStructuring Your Novel divides a story into four quarters and walks writers through the purpose of major turning points like the Inciting Event, First Plot Point, Midpoint, Third Plot Point, and Climax. K.M. Weiland builds on classic principles of storytelling while grounding them in modern narrative craft. The result is a practical guide that helps writers understand where key moments belong in a story and why they matter emotionally.

Why It WorksIt offers a clear, easy-to-follow roadmap through the stages of story developmentIt helps writers diagnose pacing issues and strengthen emotional impactThe complementary workbook makes it easy to put information from the book into practiceBONUS: Katie���s Story Structure Database examines literally hundreds of books and movies and identifies their major turning points. It���s a goldmine for learning to identify those points in familiar stories so it���s easier to incorporate them into your own.

Summary for Busy Writers: Structure doesn���t limit creativity; it supports it. When you understand how stories are built, you can write with control, shape stronger arcs, and give your readers a deep emotional experience. No matter your process, knowing the beats that make stories work will help you stay on track. Try a few of these models and see which one fits your style, genre, and the story you want to tell.

What story structure tool works best for you?

Other Posts in This Series

Dialogue Mechanics

Effective Dialogue Techniques

Semi-Colons and Other Tricky Punctuation Marks

Show-Don���t-Tell, Part 1

Show-Don���t-Tell, Part 2

Building a Balanced Character

Infodumps

Point of View Basics

Choosing the Right Details

Avoiding Purple Prose

Character Arc in a Nutshell

The post Writing 101: Popular Structure Models that Work appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 21, 2025

How To Use Dialogue for Backstory and Worldbuilding���Infodump-Free!

It���s an ongoing struggle for many of us: How do I share backstory and build my world without infodumping (and boring my readers)? One of my favorite���and sometimes overlooked���tools is dialogue!

Using dialogue���and the beats that go along with it���is an excellent way to develop character relationships, reveal secrets, and move the plot forward. But it���s also a highly effective way to write backstory and world building. There���s a right and a wrong way to do this, though. Let���s look at a few:

Using Dialogue for BackstoryDialogue is a great way to share both the history of your world and the history of individual characters. Readers often need to know what happened before, so that the now makes sense.

The Wrong WayThe rules of good dialogue apply here. In other words, people don���t speak in huge chunks of text. If your characters have thick paragraphs of dialogue because they���re explaining the history of the planet or the story behind the king���s latest military campaign, you���ve got nothing but a big ol��� infodump inside some quotation marks!

Example: Jenna frowned. ���How did this happen in the first place?���

���It���s complicated,��� Myron said. ���For one thing, no one ever wrote down the rules of engagement. Three hundred years ago, the Wisp Ghouls arrived on these shores with nothing but the leather satchels on their backs. It took them a while to settle in and establish the Sanctuary, which took almost a decade to build. By the time it was finished and they���d moved in, the Gatherings were already taking place. Most people think the Wisp Ghouls simply brought with them their own traditions, but a few think the Gatherings developed during the building of the Sanctuary, as a way to keep their magical practices clean and organized. But things change over time, you know? And now we have all sorts of factions and rules and counter-rules, and no one can be absolutely sure what the Wisp Ghouls��� original intention was.���

The Right WayTo avoid infodumping in your dialogue, you can:

Cut back on the amount of information you���re sharing.Break up the dialogue with beats and actions.Break up the dialogue with comments from other speakers.Example: Jenna frowned. ���How did this happen in the first place?���

���It���s complicated,��� Myron said. ���When the Wisp Ghouls arrived three hundred years ago, it took them nearly a decade to establish the Sanctuary. By the time they moved in, the Gatherings were already taking place.���

���Sounds like they brought their traditions with them,��� Jenna said.

���That���s what most people think,��� Myron said, ���but a few think the Gatherings developed during the building of the Sanctuary, as a way to keep their magical practices clean and organized. And now we have all sorts of factions and rules and counter-rules, and no one can be absolutely sure what the Wisp Ghouls��� original intention was.���

Using Beats and Inner Dialogue for BackstoryBeats (statements and actions between lines of dialogue) and inner dialogue (the POV character���s unspoken thoughts) are another great way to thread in backstory and worldbuilding.

The Wrong WayAgain, the key here is to avoid overwriting/infodumping. Less is more.

Example: ���Steve and Stacy never dated.��� Well, that was partially true. There had been that dinner date, two or three years ago. It was an unmitigated disaster, and Stacy refused to talk about it afterward, even though Lila had brought it up several times. She figured that, in these circumstances, ���never��� applied. ���And if anyone would know, I would.���

The Right WayWhat are the key things we need to know? Those stay, and the rest goes:

���Steve and Stacy never dated.��� Well, aside from that disastrous dinner date, two or three years ago. But Stacy had refused to talk about it afterward, so Lila figured that ���never��� applied here. ���And if anyone would know, I would.���

Using Dialogue for Worldbuilding

Dialogue is a highly effective way to share details about your world, such as:

Topography/geographyWeather/climate/seasonFantasy: magic rulesSci/fi: tech rulesCulture (politics, religion, etc.)The Wrong WayI won���t bore you with another overwritten example (you���re welcome!), but the same rule applies: LESS IS MORE. If your characters are discussing the lay of the land or trying to figure out how the weapons on a starship work, make the dialogue snappy and believable, offering just enough details for the readers to understand what���s going on.

The Right WayHere���s an example of how to do just that:

���Of course the spell didn���t work,��� Aden said. ���You didn���t take your shoes off! How do you expect the Earth energy to respond if you���re not barefoot?���

In the above example, we learn exactly why the spell doesn���t work, in the context of short, believable dialogue.

Using Beats for WorldbuildingAnd, finally, we can use beats for worldbuilding the same way we use them for backstory (carefully and sparingly!).

The Wrong WayBeats that are longer than a couple of lines or so are too much. Always keep an eye to trim, trim, trim!

The Right Way���Drink this.��� Jasmine lifted the crystal vial and swirled; the contents glowed first blue, then gold, then pure white���a perfect activation of the geraldine elements.

In the above example, we learn exactly how the magic in the vial works���in very few words!

Once you master using dialogue, beats, and inner dialogue to build your world and paint your backstory, you���ll find that your writing is clean instead of clunky, your narrative tight inside of bloated. Are you ready to kick infodumps to the curb? Dive into your dialogue and watch the magic begin!

Want to dig deeper? Sign up for Jill���s SELF-EDITING CRASH COURSE (it���s free!) to take your self-editing skills to the next level.

Summary for Busy Writers: No one wants to bore their readers with infodumps that bog down the narrative. This post examines the use of dialogue and beats for worldbuilding and backstory and offers clear examples of how to do it right.

The post How To Use Dialogue for Backstory and Worldbuilding���Infodump-Free! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 17, 2025

Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Asking for Help

When a character suffers emotional pain, the brain���s response is to stop the discomfort, and often this results in a coping mechanism being deployed. Whether it’s an automatic response or a learned go-to strategy, a mechanism helps them cope with the stress of the moment or escape the hurt of it.

But if the character develops an unhealthy reliance on that mechanism, problems will arise. Long-term, certain coping behaviors will impair their connections with others, their ability to achieve goals and dreams, and their ability to handle life’s pressures.

At some point, they must have an Aha! moment where they realize their coping method is holding them back and seek other ways to deal with stress. Namely, they���ll have to adopt healthier mechanisms that enable them to manage difficulties and ultimately have a happier future.

To help you write your character’s growth (or regression) journey, we’ve created The Coping Mechanism Thesaurus, which contains a range of coping mechanisms. The one we’re highlighting today can help your character better manage painful emotions and stress. Use this partial entry to show readers the character is choosing more productive strategies that will build resilience.

Asking for Help DefinitionOpening up to others about a personal situation and requesting support.

What It May Look LikeAsking someone to meet up to talk

Reaching out to someone from the past who was there for the character before

Offering a friend a compliment: “You give such great advice!” or “You always have a good perspective,” in hopes of being asked if they require advice about something

Answering the ���How are you?��� question honestly

Using the Band-Aid approach: “I did something stupid and need a lawyer. Yes, it���s that bad. Can you help me?”

Knowing they need help but not wanting to be viewed as incompetent or weak

Being self-sufficient to a fault (so struggling with feeling indebted to another)

Harboring resentment, believing the situation that led to needing help was unjust or unfair

Not agreeing with the ���helpful��� approach, but not being in a position to argue, either

Feeling judged or doubted (but knowing that it���s earned due to past actions)

Having to ask someone for help who will expect something in return

Needing to swallow their pride because other people told the character they couldn���t handle the situation alone, and they were right

Physiological Needs: Getting help when the situation is dire could mean the difference between surviving and perishing.

Safety and Security: In a crisis, seeking assistance can pave the way to safety and security, thereby restoring this essential need.

Love and Connection: When a character asks for help, it allows others the opportunity to show affection and love, being there for them in a moment of need. Tackling problems together strengthens relationships on both sides.

Need More Descriptive Help?

While this thesaurus is still being developed and expanded, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Asking for Help appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 15, 2025

Win Editorial Feedback on Your First 10 Pages

Want to win editorial feedback and take your story opening from good to great?

Well, my writerly friend, you’re in luck! It’s time for our monthly Phenomenal First Pages contest. In this draw, you can win…

Editorial feedback on yourfirst 10 pages

Entering is easy. Leave your contact information on this entry form (or click the graphic below). If you win the draw, we’ll let you know how to send us your pages.

Contest DetailsThis is a 24-hour contest, so enter ASAP.Make sure your contact information on the

entry form

is correct. One winner will be drawn. If you win, we’ll email instructions for submitting your first 10 pages and synopsis.Please have your pages ready in case your name is selected. Format with 1-inch margins, double-spaced, and 12pt Times New Roman font. You���ll need to supply a synopsis (a rough one is fine) so Stuart has context for his feedback.The editor you’ll be working with: Stuart Wakefield

Contest DetailsThis is a 24-hour contest, so enter ASAP.Make sure your contact information on the

entry form

is correct. One winner will be drawn. If you win, we’ll email instructions for submitting your first 10 pages and synopsis.Please have your pages ready in case your name is selected. Format with 1-inch margins, double-spaced, and 12pt Times New Roman font. You���ll need to supply a synopsis (a rough one is fine) so Stuart has context for his feedback.The editor you’ll be working with: Stuart Wakefield

With 26 years of experience in theatre, broadcast media, and coaching, I���ve developed a deep love of character and what drives them. My coaching style is warm, thoughtful, and practical���I believe writing a book can be hard sometimes, but more often than not, it should be fun.

As an Author Accelerator Certified Book Coach, I specialize in story development, with a particular focus on character backstory and emotional depth. I���ve helped writers develop powerful, satisfying stories that hold up to editorial scrutiny���and two of my clients have books coming out this year.

I hold an MA in Professional Writing, and my most recent novel, Behind the Seams, reached the semifinals of the BookLife Fiction Prize Contest, scoring 10/10 in every category. I���ve also been commissioned to write a play, and my first TV show���based around celebrity characters���is available to stream online.

Grab my free ebook on emotional resilience for writers and learn more about my services at: https://www.thebookcoach.co/

I���m also the host of the podcast Master Fiction Writing, where I explore the craft of storytelling with writers, editors, and creatives from all walks of life.

Did you know…

Some winners find their dream editor through this contest, and a few have shared with us that their polished pages have helped them secure representation. Talk about phenomenal reasons to enter!

Sign Up for Notifications:

Every month is a new chance to win feedback. Subscribe to our blog in the sidebar, and notifications about this contest and other helpful writing articles will come right to your inbox.

Good luck, everyone. We can’t wait to see who wins!

PS: To amp up your first page, grab our First Pages checklist from One Stop for Writers. For more help with story opening elements, visit this Mother Lode of First Page Resources.

The post Win Editorial Feedback on Your First 10 Pages appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 14, 2025

How to Tell the Difference Between a Hook and Inciting Incident

Opening pages are notoriously hard to get right, especially in early drafts of your manuscript. I���ve read hundreds of opening chapters of novels in my work as a writing instructor and book coach and one of the most common issues I see comes down to a misunderstanding of the difference between two key parts of your opening: the hook and the inciting incident.

The hook and the inciting incident are both story beats that should be part of the setup for Part 1 (20-25%) of your novel. They���re crucial for hooking the reader and kicking off the major action of the plot, respectively, but unless you���re writing thriller or mystery, they should not be the same beat.

Larry Brooks writes that there are ������a handful of important things Part 1 needs to accomplish��� it���s not to show the reader the big inciting incident in the first few pages���that���s called a hook, which is an important part of the setup��� (Brooks, Larry. Story Engineering (p. 146)). Lisa Cron describes the opening hook of the story as the first tick in your ticking clock, the step that ���trigger(s) your protagonist���s decision to take that first step out of her comfort zone��� (Cron, Lisa. Story Genius (p. 140)).

So how can you set up exactly the right trigger, the right hook, for your story? Let���s dig in and find out!

What Is a Beat?Ultimately, a beat is just an event that happens in the plot. All beats are important to your story, but some are more important than others. Beats like the hook, the inciting incident, the midpoint, and the climax are probably familiar to you, but if not, Resident Writing Coach Jami Gold has a solid introduction to story beats here.

How To Grab Readers, Hook, Line, And Sinker���With all the emphasis on first pages, on hooking readers (and agents!) in the first chapter, the first page, even the first sentence, it can be tempting to start your story with a huge, action-packed event. But that often backfires for a couple of reasons.

The first is because often the ���action-packed event��� (particularly if this is a death or mortal peril) would mean more to the reader if they first cared about the main character. Nobody denies the tension in seeing poor Aunt Bertha fall off a cliff on page one, but we as readers care a lot more if we know why we should care about Aunt Bertha. If we learn in the hook, for example, that our heroine was raised by Aunt Bertha and feels like she���s her only support system in an otherwise hostile and lonely world just as she���s about to face a major life challenge, then Aunt Bertha���s death has story context. If you kill poor Aunt Bertha on page one instead, you���d have to rely on flashback to establish that bond between Aunt Bertha and our heroine, thus killing all the tension and momentum you created with the fall from the cliff. So in this particular example, we might want to show just exactly how tenuous the main character���s situation is, what challenges she���s facing in her ordinary world, which will then be irrevocably upended when she finds out that Aunt Bertha is gone a bit later (at the inciting incident).

A good hook should:

Introduce the main character���s world in a tension-filled scene that demonstrates at least one of the challenges facing the character.Foreshadow the main antagonistic force and main plot that is coming.Establish the voice of the main character.Create sympathy for the main character.In short, the hook establishes the character���s ordinary world in an extraordinary way so that the reader takes the bait���hook, line, and sinker.

With The Context Established, Enter the Inciting IncidentOnce your readers are hooked, the next major story beat is the Inciting Incident. Lisa Cron describes the inciting incident as follows: ������what unavoidable external change will catapult my protagonist into the fray, triggering her internal battle? In other words, what threshold is my protagonist standing on the brink of, whether she knows it or not?��� (Cron, Lisa. Story Genius, (p. 129)). Once your main character crosses that threshold, they���ve passed a point of no return and the main plot of the story is inevitably, irrevocably set in motion.

A solid inciting incident should:

Be a moment that, given the context established in the hook and opening of the story, upends the character���s life.Set the larger plot in motion.Introduce the obstacles the character will face and a sense of the stakes if they fail.If you���ve done a good job of establishing the character���s ordinary world in the hook at the opening book and the intervening chapters leading to the inciting incident, the reader will instinctively know just exactly how the inciting incident is going to shake up the character���s life.

Some Real-World ExamplesOK, I know this is a lot, so let���s look at some examples (there will be some mild spoilers here, so read at your own risk!):

Yellowface by RF Kuang starts with a great hook���the death of the main character���s sometimes friend, sometimes professional rival, author Athena Liu. The tension is high here not just because Athena chokes to death in front of June, the main character, but because before that moment, June���s professional jealousy is clearly on display, which leads to the inciting incident���June stealing Athena���s unpublished manuscript and passing it off as her own. If RF Kuang had tried to start with the inciting incident���the stealing of the manuscript���she either would have had to hugely dip back into backstory to give the reader context or the reader just wouldn���t have known enough about June���s motivations, her sense of the injustice of her own failure to launch as an author, and all the other details of her character that bring the story to life. This is not a book where the reader has a great deal of sympathy for the main character, but at least we understand her motivations enough to suspect that she���s about to blow up her life in dramatic fashion and we���re hooked enough to go along for the ride to watch it happen.

In Helen Huang���s The Kiss Quotient, the story opens with main character Stella���s mother declaring that she���s ready to have grandchildren. The announcement begins a panic spiral that does an excellent job of character development while introducing us to one of the big impediments to Stella being able to meet her mother���s expectations: she hates the idea of having sex. The voice of this opening scene is already great at piquing the reader���s interest, but the next scene really sets the hook when we meet Philip, the colleague her parents suggest she date, and realize that he���s a terrible match for Stella. Back against the wall, Stella does what any self-respecting data scientist would: she decides to hire a male escort to teach her how to be good at sex (inciting incident) and shenanigans ensue for the rest of this hilarious and sexy gender-flipped Pretty Woman retelling.

In Six of Crows by Leigh Bardugo, the hook is a prologue that establishes the magic system of her story world. But it���s not an info-dump. Instead, it���s a vivid scene of those in power testing a drug on a prisoner with magical powers. The drug enhances her magical power to the point that she���s able to control her captors with disastrous results for these obviously bad men. Yet, the implications are clear���whoever controls this drug has access to an immense and dangerous power. This one���s a little bit of a rule breaker because we don���t start with one of the main POV characters that make up this ensemble cast, and yet it���s a brilliant hook because of the clear life or death stakes of this magic and the drug that amplifies it. So when we meet the main characters in the next several chapters and realize that several of them are also magical, the stakes are immediately raised. And when we find out they���re planning a heist that might disrupt the evil powers that be (inciting incident), we are completely invested in the characters and the world.

Now It���s Your Turn���Can you identify the hook moment and the inciting incident in your story? If not, perhaps look at a few examples from published stories in your genre/age category and then see if you can���t craft something similar for your own. Getting that hook right ensure you���re starting your story in the right place, a place that will grab readers and make sure they keep turning pages.

If you���d like a deeper dive into what makes first pages work, check out A Mother Lode of First Pages Resources and Writers Helping Writers��� First Pages Checklist.

Good news! Julie Artz will be the guest editor for our December 18 contest where winners will receive feedback on a scene up to 750 words that includes their chapter one hook.

The post How to Tell the Difference Between a Hook and Inciting Incident appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 11, 2025

Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Embracing Responsibility

When a character suffers emotional pain, the brain���s response is to stop the discomfort, and often this results in a coping mechanism being deployed. Whether it’s an automatic response or a learned go-to strategy, a mechanism helps them cope with the stress of the moment or escape the hurt of it.

But if the character develops an unhealthy reliance on that mechanism, problems will arise. Long-term, certain coping behaviors will impair their connections with others, their ability to achieve goals and dreams, and their ability to handle life’s pressures.

At some point, they must have an Aha! moment where they realize their coping method is holding them back and seek other ways to deal with stress. Namely, they���ll have to adopt healthier mechanisms that enable them to manage difficulties and ultimately have a happier future.

To help you write your character’s growth (or regression) journey, we’ve created The Coping Mechanism Thesaurus, which contains a range of coping mechanisms. The one we’re highlighting today can help your character better manage painful emotions and stress. Use this partial entry to show readers the character is choosing more productive strategies that will build resilience.

Embracing Responsibility DefinitionEmbracing responsibility is all about accepting obligations and following through, even when it feels uncomfortable.

What It May Look LikePrioritizing what���s most important

Choosing needs over wants

Following through on commitments

Being proactive and planning ahead

Not making promises they can���t keep

Wanting to take responsibility but doubting their ability to succeed

Fearing they���ll only make a mess of things

Trying to stay personally accountable when others are not doing the same

Striving to do better but struggling to regulate emotions

Not wanting to fall into the trap of overcommitting, but also wanting to please or impress others

An unforeseen factor forcing them to default on an obligation or responsibility

Having to take a medication that increases impulsivity and decreases focus

Being measured against unreasonable or unfair expectations

Being sabotaged by someone who wants the character to fail

Being blamed for something that isn���t the character���s fault

Esteem and Recognition: Taking ownership of their obligations will not only lift the character in the eyes of others but will also build up self-worth.

Love and Connection: Becoming more responsible will show others that they’re dependable and committed, which can help resolve friction and strengthen relationships.

Need More Descriptive Help?

While this thesaurus is still being developed and expanded, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Embracing Responsibility appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1023 followers