Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 3

October 7, 2025

Celebrating 10 Years at One Stop for Writers!

Happy Birthday, One Stop for Writers!

It’s hard to believe, but One Stop for Writers�� is officially TEN years old!

When Becca and I built One Stop for Writers with Lee (a software developer who also created Scrivener for Windows), all those years ago, it was a significant departure from books and blogging. But we were on a mission to make writing fiction easier for everyone–and we knew our tools would help do just that. Fast-forward to today, ten years in. We are grateful to writers everywhere for their trust in us and thrilled to be part of so many creative journeys!

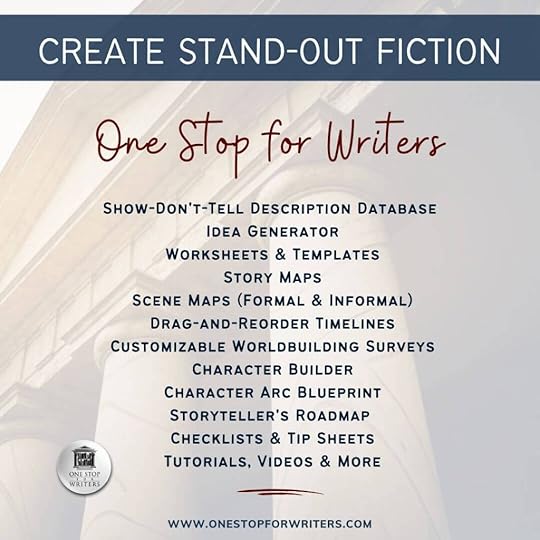

Adding more tools over the years means One Stop for Writers has truly become one of the most comprehensive story support toolkits out there. From the world���s largest show-don���t-tell thesaurus database to planners, maps, and our beloved Character Builder, we���ve loved creating resources that have helped you get your stories onto the page for readers to enjoy.

Save 25% on all plans

To celebrate a decade of storytelling together, we���ve cooked up a special thank-you. Use the code below to save 25% on any subscription plan:

10YEARS

How to use this code:

Sign up or sign in at One Stop for Writers.Choose a plan (1-month, 6-month, or 12-month) and add this code: 10 YEARS to the coupon box.Once activated via the button, a one-time 25% discount will apply onscreen.Add your payment method, check the Terms box, and then hit subscribe!And that’s it. An arsenal of tools and resources is waiting to help you plan, write, and revise!

Redeem by October 16th, 2025.

New to One Stop for Writers?If you’re not familiar with One Stop for Writers, join Becca for a virtual tour. She’ll show you how using the right tools will help you write stronger fiction faster.

Looking to grow your writing skills? Show-don’t-tell like a pro. Our free 5-minute tutorials will help you activate the power of our descriptive thesauruses!Level up all of your stories. We share a ton of writerly gold in our free Tip Sheet & Checklist Database . Bookmark, share, and download.Snoop around the One Stop Library. Start a free trial–writing can be easier!Thank you for 10 great years! We’re honored to be part of your writing process and look forward to helping you write many more stories.

The post Celebrating 10 Years at One Stop for Writers! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 4, 2025

Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Self-Medicating

When a character suffers emotional pain, the brain���s response is to stop the discomfort, and often this results in a coping mechanism being deployed. Whether it’s an automatic response or a learned go-to strategy, a mechanism helps them cope with the stress of the moment or escape the hurt of it.

But if the character develops an unhealthy reliance on that mechanism, problems will arise. Long-term, certain coping behaviors will impair their connections with others, their ability to achieve goals and dreams, and their resiliency in handling life’s pressures.

At some point, they must have an Aha! moment where they realize their coping method is holding them back and they need to seek other ways to deal with stress. Namely, they���ll have to adopt healthier mechanisms that enable them to manage difficulties and ultimately have a happier future.

To help you write your character’s growth (or regression) journey, we’ve created The Coping Mechanism Thesaurus, which contains a range of coping methods. The one we’re highlighting today can be damaging, and we hope this entry will help you show your character’s struggle in a way readers can relate to.

Self-MedicatingDEFINITIONSelf-medicating is the use of substances or soothing behaviors to handle (or avoid) unwanted emotions, stress, and circumstances.

WHAT IT MAY LOOK LIKEUsing drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, food, shopping, gambling, sex, exercise, or other substances or activities specifically to numb physical or emotional pain

Medicating at the first sign of discomfort

Loosening the guardrails around usage (medicating at work where it is prohibited, for example)

Defensiveness when asked about the activity or usage

Always ���using��� after the same triggers (at bedtime, after fighting with a spouse, etc.)…

Love and Connection: Hiding a habit from loved ones, or prioritizing it over them, will create bad feelings in the character’s important relationships. Friction will also arise when friends and family are honest and confront the character about their concerns with the activity.

Safety and Security: In extreme cases, the character may sacrifice personal finances, healthy boundaries, and their physical or mental health to engage in their self-medicating activity…

Missing important family events

Becoming less productive or reliable at work

Finances becoming strained as the usage increases

Feeling isolated from others

The character���s physical health deteriorating…

Recognizing what triggers the need to self-medicate

Minimizing time spent with bad influences

Creating a plan for when the temptation to self-medicate is strong

Learning how to have difficult conversations rather than avoid them

Being accountable if a slip happens (rather than letting their progress be derailed by it)…

Need More Descriptive Help?

While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Coping Mechanism Thesaurus Entry: Self-Medicating appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 2, 2025

What Kind of Writing Monster Is Lurking in Your Brain?

You wouldn���t think a productive writer would have to worry about monsters. But sometimes, just when you���ve cleared your schedule, opened your laptop, and promised yourself you���ll finally get that chapter (or email or video) done, something cold and invisible slinks up behind you.

Suddenly, you���re scrolling instead of writing, reorganizing your Scrivener folders, and researching branding fonts for the fifth time this week.

If that sounds familiar, here���s your diagnosis: There���s a monster in your brain.

Below, you���ll meet the four most common types that plague writers. These horrific beasts are drawn from the real patterns I���ve found in my research for my new book, Escape the Writer���s Web. Each monster represents a different conflict zone in your creative brain, and each comes with a set of tricks and a few treats to help you fight back.

Monster #1: The Whispering Wretch (a.k.a. The Inner Critic)You sit down to write or work on your marketing tasks, then find yourself endlessly editing, researching, or spiraling emotionally until you���re certain this manuscript needs to be dumped in the trash.

Meanwhile, your monster whispers things like:

���That���s not good enough.������Someone else already said it better.������Why even try?���How to Banish the Whispering WretchThis monster feeds on fear, especially fear of judgment, failure, or being seen. The goal isn���t to silence it entirely, but to shrink its power by creating safety, softening the stakes, and reducing the emotional load of showing up.

1. Lower the threat level.

The Wretch gets louder when the task feels too high-stakes, like everything hinges on this next sentence, pitch, or post. Your first move? Make what you���re tackling smaller and less ���important.���

Try this:

Write a deliberately awful paragraph just to prove the world won���t end.Rename your draft something absurd like UglyBlob_01.docx to trick your brain out of perfection mode.In marketing, post a ���throwaway��� caption in a secret document or alternate account where it doesn���t have to be polished or public.2. Break the shame spiral.

One of the Wretch���s favorite tricks is to require too much at once: write it, fix it, publish it, and defend it from judgment all in the first draft!

Try this:

First round: just ideas���no pressure.Second round: cleanup crew.Third round: polish and prep to share.When the critical voice pipes up early, say, ���This isn���t your shift yet. Come back at round three.���3. Build invisible momentum.

The Whispering Wretch thrives in stillness, particularly when you���re stuck, stalled, or staring too long at the blinking cursor. It withers when you start moving, even if the steps feel small or silly.

Try this:

Open your writing doc and type one sentence, any sentence. It doesn���t matter what it says. Then write one more.For marketing, try using a 5-minute timer to brainstorm headlines or hooks: no judgment or editing.Reward yourself for showing up, not finishing. Movement is the key measure here.Monster #2: The Ever-Hungry Howler (a.k.a. Energy-Momentum Disconnect)This monster gallops in at full speed, fangs bared, eyes wild, dripping ambition, and convinces you that now is the time to write the book, start the podcast, build the platform, update your website, grow an email list, and post three times a day on Instagram.

You feel possessed. Hyper-focused. Driven!

Until you crash. Then come the doubts, the guilt, and the scroll hole.

That���s how the Howler works: it fuels your drive until it devours your energy. The more you obey its manic rhythm, the louder it howls.

How to Banish the Ever-Hungry HowlerThis beast feeds on overcommitment and the shame that comes afterwards. The trick isn���t to work harder, but to work with your energy instead of always fighting it.

1. Create a minimum baseline.

When the Howler takes over, you believe every project matters equally, and that your success depends on doing all of it���right now.

To resist:

Choose one small keystone writing task each day (e.g., 15 minutes of drafting, one paragraph of revision).In marketing, define a single ���bare minimum��� action that keeps you visible without draining your soul. Maybe that���s scheduling one post per week or sending a once-a-month email that feels true to you.Declare your day ���done��� when that task is done. Anything else is a bonus.2. Build in recovery windows.

High creative energy is often followed by a natural lull. It would be nice if we could understand and honor that, but when haunted by the Howler, it���s impossible.

To outsmart it:

After intense writing days (or big visibility efforts like launches), pre-plan recovery time���a half day offline, a walk, a weekend away, or even just a change of scenery.Mark ���off-duty��� days in your calendar and protect them like deadlines.Let your audience or community know when you’re offline. This makes it harder for your brain to equate “not posting” with vanishing.3. Track your energy patterns, not just your progress.

We have to remember that our creative energy isn���t a machine. It���s more like a tide, and it needs to go out sometimes.

Try this:

Keep a simple journal or monthly calendar where you rate your energy on a scale of 1���5 and jot down what you worked on.Look for patterns. Are you more energized in the mornings? Mid-week? After certain types of tasks? At certain times of the month or year?Adjust your writing/marketing goals to sync with your high-output windows. Let the lows exist, remembering that they���re restorative.Monster #3: The Fogwalker (a.k.a. The Idea���Action Gap)

You���ve got ideas, so many ideas! An entire haunted library���s worth of outlines, snippets, and half-finished drafts. But when it���s time to pick one and take action, the fog rolls in. Everything feels overwhelming.

The Fogwalker doesn���t block you with fear or resistance. It just makes things too hazy to move.

How to Banish the FogwalkerThe trick is to simplify the path and reduce decision fatigue so you can move forward even when you���re not sure it���s the ���perfect��� move.

1. Limit your options.The Fogwalker grows stronger every time you stare at your ten open tabs or twelve half-outlined projects. To beat it, narrow the field.

Try this:

Choose one writing project to move forward with this month. Not forever, just for now.Pick one marketing channel to show up on consistently. Ignore the rest for 30 days.For creative ideas, make a ���Not Now��� doc. List other exciting options there, so you don���t feel like you���re losing them, but they don���t distract you either.2. Set micro-goals with visible wins.When every task feels too big or vague, your brain resists starting. Instead of ���revise chapter four��� or ���launch my Substack,��� break the fog into bite-sized chunks.

Try this:

Write one sentence. That���s it. Bonus points for a second.Create a single social post or newsletter draft���not a final version.Use sticky notes, checkboxes, or a visual tracker to see progress build. The Fogwalker hates evidence of momentum.3. Anchor your creative energy with structure.When your brain loves possibility, it rebels against rigid plans. But without some container, ideas stay floaty and the Fogwalker keeps you drifting.

Try this:

Use a weekly rhythm instead of a daily schedule. Example: Mondays = content planning, Tuesdays = drafting, Fridays = send/share.Give each idea a time limit: ���I���ll explore this story concept for 30 minutes, then decide next steps.���For marketing, try a repeatable format (e.g., a weekly ���tip Tuesday��� post or monthly ���writer behind the scenes��� email) to reduce the need for new decisions every time.Monster #4: The Rebel Revenant (a.k.a. The Autonomy Tension Trap)You meant to work on your novel or follow through on the launch plan you swore you’d stick to this time, but then you got this weird urge to do literally anything else. Suddenly, folding laundry felt like freedom.

That���s the Rebel Revenant. He shows up with defiance when a task feels imposed, forced, or loaded with expectation, or as the fun-seeker who wants novelty, dopamine, and creative freedom.

How to Banish the Rebel RevenantThis monster feeds on anything that feels like it���s boring or like you ���should��� do it. The trick isn���t to push harder, but to reframe the task so it feels like a fun choice, not a drab command.

1. Make it yours.To reclaim your creative fire, you need to feel like you���re driving instead of being dragged.

Try this:

Reword your to-dos in your own voice. Instead of ���Outline chapter three,��� try ���Play with what happens next.���For marketing, stop copying someone else���s formula. Create your own version of visibility. Hate video? Try audio. Hate social media? Focus on email or collaborations.Ask yourself: ���If I were doing this my way, what would that look like?���2. Add play���or a tiny rebellion.If it feels too serious or structured, you���ll ghost it. So bend the rules. Add a twist.

Try this:

Set a kitchen timer and race yourself. Write one messy paragraph before it dings.For marketing, post something honest, weird, or wildly off-brand just to see what happens.Give yourself one ���free pass��� day per week with no guilt. When you know you���re allowed to skip, you’re less likely to do so.3. Create goals that leave room to roam.Rigid checklists make the Rebel Revenant cranky. You need structure, but with wiggle room.

Try this:

Set flexible outcome-based goals. Instead of ���write every day,��� try ���finish two scenes this week.���Pick from a menu of tasks: ���Today I���ll do one of these five things.��� (Not all, just one.)For marketing, build in spontaneity. Have a list of quick ���fun��� posts or ideas you can draw from when the mood strikes.What���s Your Monster?I created a free quiz to help you identify which monster has been haunting you (in non-Halloween language). It takes just a few minutes, and the results will give you real insight into why you keep stalling out.

Go on. Shine a flashlight into the dark corners of your writing brain. What you find might finally set you free.

The post What Kind of Writing Monster Is Lurking in Your Brain? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 30, 2025

Meet Our 2025 – 2026 Resident Writing Coaches

I love being the Writers Helping Writers Blog Wizard���and am honored to work closely with the Resident Writing Coaches. They���re all talented, generous authors who share their wisdom to help take your writing to the next level. I’ve learned so much from them, and have a feeling you have, too!

This is the 10th year of our popular Resident Writing Coach program where we feature writing experts through a series of four blog posts scattered throughout the year. We bring in a mix of expertise, so you benefit from different voices and perspectives from all over the world.

Each year we have some new coaches and some returning, so let me first say goodbye to the wonderful Marissa Graff and Christina Delay. We greatly appreciate all they have shared with us. I’m thrilled that Marissa will be our guest editor for several upcoming critique contests, and hope she and Christina will be back as coaches in the future.

I���m excited to welcome two amazing Resident Writing Coaches. Please give a warm welcome to���

Jill Boehme was known for many years to the online writing community as Authoress, hostess of Miss Snark���s First Victim, a now-retired blog. She is the author of Stormrise and The Stolen Kingdom; she is also a writing coach, a freelance editor, and a staunch defender of the Oxford comma.

You will also find Jill teaching writing classes both locally and online. She finds great joy in encouraging and inspiring writers.

Julie Artz helps status quo busting writers slay their doubt demons and get their stories reader-ready. She is an Author Accelerator-certified Founding Book Coach and a sought-after writing instructor and speaker. She regularly contributes to Jane Friedman and Writers Helping Writers, and is an instructor for AuthorsPublish. A consummate social justice minded story geek, Julie lives by an enchanted river in Fort Collins, Colorado with her husband, two naughty furry familiars, and two college-aged children who occasionally manifest.

You can find her on Youtube and Substack.��

Is Your Story Reader-Ready? Take the quiz to find out.

In addition to our new coaches, we���re thrilled to have these returning masterminds���

Lucy V. Hay is a UK-based script editor & reader, and creator of the popular site, Bang2Write, a top screenwriting blog topping industry lists such as Writer���s Digest���s 101 Best Websites for Writers. She���s edited UK features and shorts for 20+ years and authored the bestselling Writing & Selling Thriller Screenplays. Her alter-ego, Lizzie Fry, pens dark thrillers including her latest, The Good Mother. You can find Lucy at her thriving Bang2Write community, helping writers improve their craft through insightful, real-world advice.

Colleen M. Story writes award-winning historical fantasy, supernatural thrillers, and motivational books for writers. Her latest, Escape the Writer���s Web, reveals a breakthrough method for overcoming procrastination. On YouTube, she helps writers stay motivated, focused, and creatively aligned, and through MasterWriterMindset.com, offers immersive workshops and unconventional tools for stuck writers. A freelance health writer, Colleen also speaks at writing conferences across North America. Find all her books at ColleenMStory.com.

Jami Gold is an award-winning paranormal romance author and blogger whose site was recognized by Writer���s Digest as a 101 Best Website for Writers. Her massive collection of resources for writers include popular worksheets (including the Romance Beat Sheet), workshops, and over 1000 posts on her blog. Jami is known for her deep dives into all aspects of craft, business, and life of writing and has helped tens of thousands of writers over the years.

Lisa Poisso is a book coach, editor, and writer with a background in journalism, communications, and magazine publishing. She specializes in working with new and emerging writers to create commercial fiction with emotional resonance. Her structured, artistry-meets-craft approach draws on her early training in classical dance. Lisa curates the popular Writes of Fiction newsletter and coaches alongside her pack of #45mphcouchpotato greyhounds.

Suzy Vadori is the award-winning author of The Fountain Series, a certified book coach with Author Accelerator, and founder of Wicked Good Fiction Bootcamp. She works with writers new to the industry, offering developmental editing, coaching, and online courses. Her superpower is tirelessly working to simplify complex craft topics to get writers up to speed and motivating them to reach their full potential.

Michelle Barker is an award-winning author, editor, and writing teacher based in Vancouver, Canada. Her novel, The House of One Thousand Eyes, won numerous awards and was named a Kirkus Best Book of the Year. She���s also co-authored Story Skeleton: The Classics and Immersion and Emotion: The Two Pillars of Storytelling with David Griffin Brown. Michelle loves working closely with writers to hone their manuscripts as a senior editor at The Darling Axe.

Jenny Hansen is a copywriter, brand storyteller, and LinkedIn coach by day, and a writer at night, working on memoir, humor, and women���s fiction. She���s a co-founder of Writers in the Storm, a long-running craft blog named to Writer���s Digest���s 101 Best Websites list. Jenny���s writing is known for a blend of heart and wit and she���s currently revising a memoir based on her cancer journey.

Tip: Love a post? Click on the name up top to see all the posts from that person.

Here���s to another year of amazing posts. Please give a warm welcome our Resident Writing Coaches.

Pssst���when you comment on their posts, they reply to you! So please share your thoughts and ask questions throughout the year. Angela, Becca and I love working with the coaches. They���re an incredible asset to the Writers Helping Writers blog.

If there���s a topic you���d like help with, please add it in the comments so hopefully one of our Resident Writing Coaches will post about it.The post Meet Our 2025 – 2026 Resident Writing Coaches appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 27, 2025

The Coping Mechanism Thesaurus is Coming!

Characters don���t always react to stress and threats in healthy ways–like real people, they lean on coping strategies they���ve developed to survive past trauma and avoid new pain. These dysfunctional coping mechanisms consist of behaviors and thought patterns designed to keep discomfort at bay. But habits formed in the past can become obstacles in the present.

Unhealthy mechanisms are forms of emotional shielding meant to protect the character from harm���specifically, from the recurrence of a past wounding event. And many times, they do keep those traumas from repeating. But they also create new difficulties. Practices like denial, avoidance, overindulgence, and self-sabotage generate issues that reverberate through their relationships, work performance, personal satisfaction, and the pursuit of their story goal.

Over the course of a story, the character must become aware of their go-to mechanism, realize how it���s holding them back, and replace it with healthy coping methods that will get them where they want to go. In this way, coping methods will play a key role in your character���s arc.

To help you write a transformation journey that���s authentic and complete, we���re launching The Coping Mechanism Thesaurus. Each Saturday, we���ll share a coping method that���s common to the human experience and could play into your character���s story. Here���s a sneak peek at what each entry will include.

What the Mechanism Looks LikeCoping behaviors show up in all kinds of ways���through speech, body language, habits, and emotional reactions. The content in this field will include a variety or fight, flight, and freeze responses associated with this mechanism. Showing these responses in believable ways builds realism and gives readers insight into what���s going on with the character under the surface.

Basic Human NeedsCoping mechanisms are tightly linked to a core element of character arc: basic human needs. Unhealthy mechanisms rob the character of a vital need, creating a void that they���ll go to great (and dysfunctional) lengths to fill. On the flip side, healthy mechanisms refill the hole. Knowing what mechanism will need to be replaced is the key to helping your character regain balance and learn positive methods that will help them achieve their goals and face difficulties in productive ways.

Fallout (And Possible Turning Points)Many unhealthy coping mechanisms start out as a benign behavior or attitude. They only become a problem when the character takes them to an extreme, can no longer function without them, and continues relying on them despite the damage they cause. The Fallout field is meant to show authors the many ways a coping method wreaks havoc. Then they can incorporate it into the character���s life so they���ll eventually see the need for change.

Challenges That Will Test the CharacterGrowth doesn���t happen immediately. Once a character realizes their current methods aren���t working for them, they���ll try a different one. But old habits die hard, and regression is a normal part of any transformation journey. Each healthy coping mechanism comes with its own challenges that can tempt the character to throw in the towel and revert to what���s comfortable. Likewise, certain internal struggles will make it harder for them to stick with the program long enough to effect change and see the benefits of coping in positive ways.

Pathways to Changing Unhealthy MechanismsTo complete a personal transformation, the character will need to discard their half-hearted attempts and fully commit themselves to change. By the story���s end, they���ll have embraced some mental shifts and new habits to show they���ve gone all in and are committed to the long-term work of healing. This field gives writers options for what true commitment to unloading the unhealthy mechanism looks like.

Final ThoughtsThe Coping Mechanism Thesaurus is designed to help you write both healthy and unhealthy methods with depth and nuance. We hope the entries we share will give you the tools to chart your character���s path to change and wholeness.

Frequently Asked QuestionsWhere Can I Buy This Book?Unfortunately, the Character Secret Thesaurus isn���t a book yet. When we introduce a new thesaurus on the blog, it means we���ve only started writing it. Our process is to ���test��� each new thesaurus here at Writers Helping Writers by posting a new entry each Saturday. If, over time, we receive feedback that writers find the thesaurus helpful and would like to see it become a book, we mark it as a possible book project for the future

Can I do something to ensurethis thesaurus becomes a book?

Yes! Take a minute to leave a comment on any of our Character Secret posts saying this topic will help you so we know! Another huge way to muster support for this thesaurus is to share links to it on social media or in writers��� groups so others know help is available in this area. The resulting boost in traffic here tells us the thesaurus is a popular one. (Thank you for doing this���we appreciate word of mouth!)

Will the book version be the same as the blog version?What you see here on the blog is only a fraction of what you���d see in a book, for a few reasons:

We only explore some secrets here, whereas the book will have many, many moreWe���re a huge target of AI scraping, which forces us to limit the content we share freely here.Each book also includes an expansive ���how-to��� section that explores how to use the thesaurus topic in a story more effectively. Our biggest mission is to help writers grow their craft, because great stories get noticed!How can I stay in the loop when you release a new book?We have an email list you can sign up for. We���ll send a note when a release date is coming, and then again when the book is available. (Thank you for asking!)

Is this Thesaurus at One Stop for Writers?Not just yet. We always wait until we have many thesaurus entries written before we add them to our show-don���t-tell database there. In the meantime, the One Stop THESAURUS is worth checking out since it contains all the thesauruses we���ve created to date (18) vs. how many exist in book form (10).

Is there a question I didn���t answer? Just leave it in the comments!

The post The Coping Mechanism Thesaurus is Coming! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 25, 2025

Writing 101: How to Find & Write Your Character���s Voice

Writing a strong and consistent character voice is one of the best ways to make your story stand out. A unique voice tailored to your character makes them feel real and more memorable to readers.

But voice is tricky to get right. Too little attention to this important aspect of storytelling results in all the author���s stories sounding the same because they���re written in their voice. And the characters fade into the background. A well-written voice, on the other hand, reflects personality, background, worldview, and emotional state, among other things. Together, they combine to create an individual voice that fits them perfectly.

Angela and I know how hard it is to nail the character���s voice, so we���ve curated quite a few posts at Writers Helping Writers on this topic. Rather than rehash what���s already been shared so well, I thought I���d gather some of those resources here, for easy reference. Hopefully these strategies will help you uncover your character���s voice and write it in such a way that readers will be hearing it long after the story is finished.

Character Voice vs. Author VoiceIt���s easy when you���re writing a story to tell it in your own authorial voice. But the voice should reflect whoever���s narrating the story, showing their view of the world. Understanding the key differences between character voice and authorial voice will help you stay in your character���s mindset. This is especially important when you���re writing in a close point of view.

Interview Your CharacterTo know how your character sounds, you have to know who they are. Interviewing a character���asking them detailed, open-ended questions���can reveal their emotional patterns, values, beliefs, and opinions. These insights reveal the lens through which they experience the world, and once you get a feel for that, their voice is easier to write.

(Read the post)

Know How They TalkThis is what comes to mind when we think of a character���s voice���their word choice, speed and cadence, patterns,and tone. How their speech sounds is a result of where they���ve lived, their education, and (again) their personality. More than just accents or slang, it���s about capturing the nuance of how they talk. Giving each character a clearly defined way of speaking makes them uniquely individual and provides readers with clues to who they are.

(Read the post)

Use Body Language to Show VoiceWhen it comes to voice, we typically think of speech and how the person talks. But that���s just part of the picture. Body language is a pivotal piece of how the character expresses themselves, and it���s dictated by their personality, emotional range, and comfort level with others. When you can show their body language, tendencies you���ve provided another piece of the voice puzzle.

Understand Their Internal WorldYour narrator���s inner dialogue���what they think and how they think it���will be played out on the pages as they tell the story. This key part of their voice will reveal their emotional makeup, self-talk, coping habits, worldview, and problem-solving behaviors. It also provides insight into how they process the people and challenges they���ll encounter.

Your narrator���s voice should be revealing, providing clues to their backstory and character. Once you determine their speech patterns, how they move, their most formative experiences, and what���s important to them���the voice tends to write itself. At that point, it���s just a matter of writing it consistently to make the character believable and interesting to readers.

For more help writing character voice and understanding other key aspects of storytelling, visit our Other Story Elements page.

Other Posts in This Series

Dialogue Mechanics

Effective Dialogue Techniques

Semi-Colons and Other Tricky Punctuation Marks

Show-Don���t-Tell, Part 1

Show-Don���t-Tell, Part 2

Infodumps

Point of View Basics

Choosing the Right Details

Avoiding Purple Prose

Character Arc in a Nutshell

The post Writing 101: How to Find & Write Your Character���s Voice appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 23, 2025

How to Use Weather to Create Mood, Not Clich��s

Are you afraid of using the weather in your writing? If so, you’re not alone. After all, if not careful, weather description can be a minefield of clich��s. The sunny, cloudless afternoon at the beach. The gloomy rainstorm at a funeral. Overdone setting and weather pairings can lie flat on the page.

Then there’s the danger that comes with using weather to mirror a character���s inner emotional landscape. Mishandling this technique can quickly create melodrama. We’ve all read a battle scene where lightning crackles as our protagonist leaps forward to hack down his foe in desperation. And how about that turbulent teen breakup where the character’s tears mix with falling rain? Unfortunately these have been used so much that most readers tilt their head and think, Really? when they read a description like this.

Agents and editors on first page panels never fail to reject a few openings that start with the weather, either. Why? Because done poorly, it comes across like a weather report, and delays the introduction of the hero. Readers are not always patient and we should strive to introduce our characters and what they are up against as soon as possible.

Wow, weather sounds like a recipe for disaster, doesn’t it? It���s no wonder that some writers are so nervous about using it they cut it from their manuscript. But here���s the thing���avoiding weather in fiction can be a fatal mistake.

Make Weather Your FriendWeather is rich. Powerful. It is infused with symbolism and meaning. And most of all, weather is important to us as people. We interact with it each day. It affects us in many subtle ways. In fact, let���s test this by walking in a character���s shoes.

Think about walking down a street. It���s late afternoon, crystal bright, and a hot breeze blows against you. School���s out and kids run willy-nilly down the sidewalk, laughter ringing the air as they race to the corner store for a grape slush. Your sandals click against the pavement as you turn down between two brick buildings. The side door to an Italian restaurant is just past a rusty dumpster, and your fianc��e���s shift is about to end. You smile, feeling light. You can���t wait to see him.

Now, let���s change the scene.

It���s sunset, and the weather has soured. Dark clouds pack the sky, creating a churning knot of cement above you. The sidewalk is deserted, and the wind is edged in cold, slapping your dress against your legs as you walk. You wish you���d worn pants, wish you���d brought a sweater. In the alley, garbage scrapes against the greasy pavement and the restaurant���s dumpster has been swallowed by thick shadow. The side door is only a few steps away. You can���t quite see it, and while all you have to do is cross the distance and knock, you hesitate, eyeing the darkness.

The same setting, the same event. Yet, the mood and tone shifted, all because of the weather I included in the backdrop. What was safe and bright and clean became dark and alien. This the power of weather–changing how people feel about their surroundings.

Steering Your Reader’s EmotionsReaders bring the real world with them when they enter a story. Avoiding weather description will be noticed as it’s such a natural part of the everyday, and it becomes a missed opportunity to steer how our readers feel.

Weather is a tool to evoke mood, guiding the character toward the emotions we want them to feel, and by extension, the reader as well. By tuning into specific weather conditions, a character may feel safe, or off balance. Weather can work for or against the character, creating conflict, tension, and be used to foreshadow, hinting that something is about to happen.

Because we have all experienced different types of weather ourselves, when we read about it within a scene, it reminds us of our own past, and the emotions we felt at the time. So, not only does weather add a large element of mood to the setting, it also encourages readers to identify with the character���s experience on a personal level.

How Do We Write Weather in a Clear Way and Stay Away From Pitfalls?Use Fresh, Sensory Images. In each passage, I utilized several senses to describe the effects of the weather. A hot breeze. Garbage scraping against the greasy pavement. A wind edged in cold, slapping against the legs. By describing weather by sound, touch and sight, I was able to make the scene feel real.

Avoid Direct Emotion-to-Weather Clich��s. There are some pairings we should avoid as I mentioned above, and with so many different types of weather elements we really need to think past the usual ones. Avoid mirroring and instead show the character���s reaction to the weather. This is a stronger way to indicate their emotions without being too direct.

Choose Each Setting with Care. Setting and Weather should work together, either through contrast or comparison. In the first scene, we have beautiful weather and an alley as a final destination. These two are contrasts���one desirable, one not, but I chose to show enthusiasm and anticipation for the meeting to win out. In the second, the weather becomes a storm. Now we have two undesirable elements, and as such, they work together to build unease.

Weather can have a positive or negative effect on setting and change the character���s reaction to it, so don���t be afraid to use it! Just remember that with something this powerful, a light touch is all that is needed.

Would you like help brainstorming descriptions for different types of weather?

Check out our comprehensive Weather Thesaurus at One Stop for Writers. There you can access all sorts of weather phenomenon, and the sights, smells, sounds, tastes and textures that will help you show, not tell, building in the exact emotional mood you want for each scene.

Great news! Check out this post to get 25% off any One Stop for Writers plan through September 25, 2025!

How do you use weather in your stories?The post How to Use Weather to Create Mood, Not Clich��s appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 17, 2025

Win Feedback on Your First 3 Pages & Blurb

Good news, wonderful

writerly people���it���s time for our monthly Phenomenal First Pages contest, where we help transform your story���s opening from good to great!

If you need a bit of help with your opening, today’s the day to enter for a chance to win professional feedback! (We’ve had past winners tell us they’ve found their dream editors through this contest, and even ended up with offers of representation!)

Five winners will receive feedback on their first 3 pages and blurb!Entering is easy. All you need to do is leave your contact information on this entry form (or click the graphic below). If you are a winner, we’ll notify you and explain how to send us your pages and blurb.

How Do You Write an Amazing Book Blurb?

How Do You Write an Amazing Book Blurb? Writing a strong book blurb is important–whether it’s for the back of your book or to entice an agent or editor to read your query.

Here are several helpful posts:

How to Craft a Top-Notch Blurb

Back Cover Copy Formula

Blurbs that Bore, Blurbs that Blare

I���m Erica Converso, author of the Five Stones Pentalogy (affiliate link). I love chocolate, animals, anime, musicals, and lots and lots of books ��� though not necessarily in that order. In addition to my work as an author, I have been an intern at Marvel Comics, a college essay tutor, and a database and emerging technologies librarian. Between helping adult patrons in the reference section and mentoring teens in the evening reading programs, I was also the resident research expert for anyone requiring more in-depth information for a project.

As an editor, I aim to improve and polish your work to a professional level, while also teaching you to hone your craft and learn from previous mistakes. With every piece I edit, I see the author as both client and student. I believe that every manuscript presents an opportunity to grow as a writer, and a good editor should teach you about your strengths and weaknesses so that you can return to your writing more confident in your skills. Visit my website astrioncreative.com for more information on my books and editing and coaching services.

Sign Up for Notifications!

If you���d like to be notified about our monthly Phenomenal First Pages contest, subscribe to blog notifications in this sidebar.

Good luck, everyone. We can’t wait to see who wins!

PS: To amp up your first page, grab our First Pages checklist from One Stop for Writers. For more help with story opening elements, visit this Mother Lode of First Page Resources.

The post Win Feedback on Your First 3 Pages & Blurb appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 16, 2025

How To Push Past The Fear of Never Getting Published

“What If No One Ever Publishes My Work?”

“What If No One Ever Publishes My Work?”If you’re worried that no publisher will pick YOUR novel, you’re not alone. This is a fear I’d venture 100% of authors have … and of course, it may even come true. Most of us will have at least one book we query that does not sell!

However, rejection is frequently most painful at the beginning of our writing careers. Not getting off the starter blocks straight away can feel awful, or even like an omen. After all, if we were ‘meant’ to be authors, then agents and publishers would snap up our books … right?

WRONG! Just because your book does not get published does not mean you’re automatically doomed. Plus acknowledging that literally every writer has this worry can help. Normalizing it and talking about it can only help us. Ready? Then let’s go …

Tip # 1: Name The Fear!The worry you will ‘never’ be published comes from self-doubt. That’s why we need to crush self-doubt wherever possible. We can do this by identifying common thought spirals and rejecting them, such as …

���I���m not talented enough.��� ��Seriously, how do you know this? Authors are notoriously bad at running themselves down. Besides, you may have someone’s favorite book of all time inside you. ���I���ve already failed.����� Authors frequently skip ahead and tell themselves they’ve failed already. They do this because it seems ‘realistic’ and might help ‘manage expectations’. But guess what? This tactic won’t make rejection hurt any less, so you might as well hope for the best outcome! “The gatekeepers are against me”. ��Some authors like to imagine the industry is against them to help fend off disappointment. Whilst the industry is hierarchical, ultimately it wants great stories, well told. That can be YOU, no matter your background.Naming the fear stops it from controlling you in the background. Don’t let it suck you under and hack your brain.

Tip # 2: ��Redefining What ���Published��� MeansIn ye olden days of just 15-20 years ago, publishing was very much a closed shop. You had to get a literary agent, who in turn would take your book to the Big Publishers and a small selection of Indies. That was the only route in.

Yet nowadays, authors have more options than they’ve ever had. The digital revolution with the Kindle, Kobo, KDP etc has changed everything. There are more indie publishers, digital-firsts, micropresses and self-publishing than ever.

This means that in real terms, it’s actually impossible not to get published … because you can learn how and do it yourself!

This fear often comes from a narrow definition of ‘success’, especially when authors see self-publishing as a last resort.

In real terms, self-publishing can be amazing. You can have more control and even make more money than a traditional deal!

Instead of looking at the industry the ‘old’ way, look at it with NEW eyes. Instead of thinking, ‘I want a traditional publishing deal or I am a failure’, think how can I SHARE my writing with the world?

Flipping that mindset switch can make all the difference!

Tip # 3: Building Resilience as a WriterPersistence is the key skill in any author’s toolkit. Various things will happen in not only writing, editing and submitting your novel, but in the publishing of it as well.

There will even be times you do everything you’re supposed to, but someone else drops the ball. That is inevitable. Cultivating resilience is all about creating strategies to help you keep on keeping on:

Rejections as data, not verdicts.Tracking small wins (shortlists, personalized feedback, finished drafts).Building a writing practice that is not solely outcome-based.Keep your feet on the ground any way you can. As the saying goes, novel writing is a marathon, not a sprint!

Tip # 4: Community, Not Competition

It’s true that many of our loved ones don’t truly get what it’s like to be a writer. This is why finding peers who do can really help ease the loneliness of the fear.

Writing groups, events and online communities can be great places to share the struggle. Knowing that others have to face climbing the same wall helps you keep climbing it!

Tip # 5: Action Beats AnxietyFear can make you stand still because it thrives in stagnation. In contrast, movement shrinks the fear … which is why it’s a GREAT IDEA to keep going! Here’s some ideas of how to do that …

Make submissions, often. Whether you’re sending to agents, contests, anthologies, writing websites, magazines or journals, keep at it. If it’s scary, then it’s working.Keep on learning!��Be a student of the craft. Keep going to workshops, reading books, getting feedback.Take back your power.��Publishers and agents love autonomous writers. Build your platform. Start small with your own blog, TikTok, IG, email list, book club or similar. Create a following by having fun, doing what you love.The progress you make will help give you confidence … and take you where you want to be. What’s not to like?

Last PointsFear is part of the writing journey, but it doesn���t have to dictate it. Your only job is to keep writing, keep submitting, keep showing up. Publishing may take longer than you want, but every word written is proof you haven���t let fear win.

Good Luck!The post How To Push Past The Fear of Never Getting Published appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 10, 2025

How to Show Your Character���s Repressed Emotions

Crafting characters that readers will connect to is every writer���s goal and dozens (hundreds?) of methods exist to achieve it: deep backstory planning, character profile sheets, questionnaires, etc.

Regardless of the roadmap a writer uses, writing an authentic character boils down to one important action: intentionally drawing from the real world, and specifically, the human experience.

The human experience is powerful, an emotional tidal wave that holds us in thrall. We understand it, relate to it, and live it. This is why, even when a character faces a challenge, barrier, or struggle that readers have not experienced in the real world, they can imagine it and place themselves within the folds of the character���s viewpoint.

Portraying an accurate mirror of humanity in fiction means we must master emotions. Getting raw feelings on the page isn���t done solely through a character���s shrug or smile; instead, a marriage of internal and external elements should show readers what is being felt and why. Body language, behavior, dialogue, vocal cues, thoughts, and internal sensations weave together to draw readers into the character���s emotional landscape.

Showing a character���s emotions isn���t always easy, especially when powerful emotions are at work. Characters may feel exposed or unsafe and instinctively try to repress or disguise what they feel. This creates a big challenge for writers: how do we show readers what the character is feeling when they are trying so hard to hide it?

Thankfully again, the human experience comes to the rescue. If a character is repressing an emotion, real-world behaviors can show it. Readers will catch on because they���ll recognize their own attempts to hide their feelings. Here���s a few ideas.

Over and UnderreactionsWhen you���ve done the background work on a character, you know how they���ll react to ordinary stimuli and will be able to write reliable responses. Readers become familiar with the character���s emotional range and have an idea what to expect. So when the character responds to a situation in an unexpected way, it sends up an alert for readers that says, ���Pay attention! This is important.���

A character may fly off the handle at something that seems benign or behave subdued in a situation that should have them upset. When this happens, these unusual responses signal that something more is going on, and the reader is hooked, wanting to uncover the why behind this unexpected behavior.

Tics and TellsNo matter how adept a character is at hiding their feelings, they all have their own tells��� subtle and unintentional mannerisms that hint at deception. As the author, you should know your characters intimately. Take a close look at them and figure out what might happen with their body when they���re being dishonest. It could be a physical signal or behavior, such as covering the mouth, spinning a wedding ring, or hiding the hands from view. Maybe it���s a vocal cue like throat-clearing. It might be a true tic, like a muscle twitch or excessive blinking. Figure out what makes sense for your character, then employ that tell when they���re hiding something. Readers will pick up on it and realize that, when it���s in play, everything is not as it seems.

Fight, Flight, or Freeze Responses

In the most general sense, the fight-flight-freeze response is the body���s physiological reaction to a real or perceived threat. We see this in everyday interactions: when a person invades someone���s space, stops what they���re doing mid-action, or literally flees the scene. It also happens on a smaller scale in our conversations. Remember that every character has a purpose for engaging with others. When that purpose is threatened, or the character feels unsafe, the fight-flight-freeze reflex kicks in.

Fight responses are confrontational in nature and may include the character turning toward an opponent to face them directly, squaring up her body to make herself look bigger, or insulting the person to put them on the offensive.Characters who lean toward flight will have reactions centering around escape: changing the subject, disengaging from a conversation, or fabricating a reason to leave.If the character���s fear or anxiety is triggered, they may simply freeze up, losing their ability to process the situation or find the words they need until something external happens to free them.Passive-Aggressive ReactionsPassive aggression is a covert way of expressing anger. If a character is angry but doesn���t feel comfortable showing it, they���ll often default to certain techniques that will allow them to get back at the person without revealing how they really feel. By employing sarcasm, framing insults as jokes, giving backhanding compliments, and not saying what they really mean (We���re good��or I���ll get right on that), characters are able to express their feelings in an underhanded way that others may not recognize or know how to deal with.

This can be a tricky technique to use, because, by definition, passive aggression masks the truth. But you can reveal it through a character���s thoughts, the physical signals they exhibit in private (particularly just after an interaction), and the cues they express when the other person isn���t looking.

IncongruenciesThe most common way to show hidden feelings is to highlight the incongruency that occurs when the character tries to mask one emotion by adopting the behavior of another. Imagine a character saying ���Come in, I���d love for us to visit��� but their body betrays the untruth of these words, perhaps through a strained voice, by closing of the door an inch rather than pulling it open wider in welcome, or by the keyring in their fist with the largest key thrusting out between two knuckles like a weapon.

If the reader is in the character���s POV, thoughts can also counterweight behavior or to provide context if the character is hiding true emotions out of fear. Incongruencies work well because all people use them to maintain the status quo in a relationship or stabilize a situation.

Reveal Hidden Feelings with Subtext.

Reveal Hidden Feelings with Subtext. Use dialogue and nonverbal cues to show your characters’ unspoken emotions and add depth to conversations. Readers will love piecing together what���s left unsaid, and their connection to your story will be heightened.

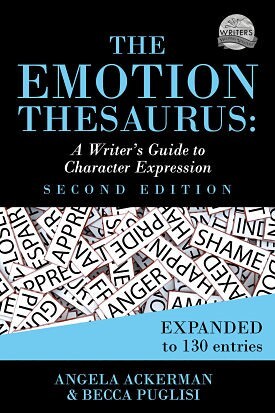

The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer���s Guide to Character Expression is a treasure trove of information on how to show exactly what your character���s feeling���even when they want to keep it hidden.

The post How to Show Your Character���s Repressed Emotions appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1023 followers