Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 61

August 31, 2021

Testing Fate: A Closer Look at Person vs. Fate Conflict

By September Fawkes

Conflict is key to writing great stories. And while writers may categorize conflict differently, I categorize conflict into eight types:

Person vs. Self

Person vs. Person

Person vs. Nature

Person vs. Society

Person vs. God

Person vs. Fate

Person vs. the Supernatural

Person vs. Technology

In today’s modern times, the Person vs. God conflict often gets left off lists or is combined with or even replaced by the Person vs. Fate conflict. But because fate conflicts don’t necessarily have gods, and god conflicts don’t necessarily include fate, I put them in separate categories.

Out of all the conflict types, Person vs. Fate is often the most misunderstood.Many of us were introduced to the concept of person vs. fate through classic tragedies where the protagonist was foretold a future that led him to a dreadful end (like in Oedipus Rex or Macbeth). This has led some to proclaim that the person vs. fate conflict is unpopular or even outdated, and has also led some writers to shortchange this conflict type (if they even give it much thought). In reality, a fate conflict happens whenever a character is struggling with a destiny–something is predetermined or foreordained, and the character somehow opposes that. What is foretold need not always be tragic or lead to a dreadful end. Arguably, it need not always even be otherworldly.

In fantasy, fate often comes from a prophecy. In Harry Potter and the Half-blood Prince, Harry struggles with the prophecy that neither he nor Voldemort can really live while the other survives. In horror, this may be a kind of curse. In Final Destination, the characters are trying to cheat their deaths–they are fated to die. It can even play into the concept of the universe having an order or law that must be upheld or fulfilled. In The Lion King, Simba must embrace his destiny as the one true king to bring order to the Circle of Life. And if we broaden the concept a little more, we can find foretold fates in the normal world; in The Fault in Our Stars by John Green, Hazel is fated to die from terminal cancer.

Person vs. fate conflicts are very effective because they get the audience to anticipate a future outcome, which is exactly how we hook and reel the audience in. Readers will want to keep reading to see if what is expected to happen actually does happen, and they will want to know how it happens. So the person vs. fate conflict has some innate strengths.

Many fate conflicts are rendered as teasers. Some characters have premonitions in dreams or visions that only reveal a snippet of fate. Prophecies are often worded in ambiguous or metaphorical ways, giving rise to multiple interpretations. Teasers don’t tell readers specifics, but they promise that the specifics will come if the reader keeps reading. So, the reader keeps reading. This also introduces a sense of mystery. Some fate conflicts work as a riddle that the audience gets to participate in, which pulls them even deeper into the narrative.

Usually person vs. fate conflicts explore free will within strict limitations. While some writers choose to ultimately emphasize a lack of free will, others choose to emphasize the power of free will. In Oedipus Rex characters try to change fate and end up bringing it about. In Harry Potter and the Half-blood Prince, Harry eventually realizes he has a choice to accept his role or not, and chooses to rise to the occasion. Characters destined to die, may have a moment where they decide how they will face that death.

How the character chooses to deal with the fate is often just as (if not more) interesting than the fate itself. The character may openly fight against fate like Oedipus Rex, or the character may have more of a personal struggle with accepting the fate and its costs, like Simba. The audience may be invited to consider whether it���s worth the cost. In Dr. Faustus by Christopher Marlowe, Dr. Faustus sells his soul to the devil to gain all knowledge. Was gaining all knowledge worth a fate in hell?

We often think of fate conflicts coming from some force beyond the character���s power, but sometimes it���s interesting when the character makes a choice that leads to an inevitable fate, such as Dr. Faustus, or even Jack Sparrow, who makes a deal with Davy Jones in exchange for the Black Pearl in Pirates of the Caribbean.

Fate conflicts traditionally come from the supernatural: prophecies, premonitions, curses, fortunes and predictions, a universal law, magical debts, or the will of otherworldly entities. But the concept can be broadened to include real-world fates: terminal illness, death row and other court sentences, forced marriage, being made a scapegoat, or forced labor. Admittedly, some conflict types can overlap with others, but looking at conflicts from a fate angle may open up your stories to new possibilities.

A few more examples of fate conflicts:

Curses, like in The Ring, where a video is promised to kill the viewer in seven days.Deals, like in��Pirates of the Caribbean, where Jack is in debt to Davy Jones and must join The Flying Dutchman or be taken by the KrakenFortunes and predictions, like in��The Raven Boys��by Maggie Stiefvater, where Blue is told that if she kisses her true love, he will dieSupernatural entities, like in��A Christmas Carol��by Charles Dickens, where a ghost tells Scrooge of his coming deathWhat have you noticed about fate conflicts? Have you ever written, or do you plan to write about a fate conflict? What do you like about them?Note from Angela:

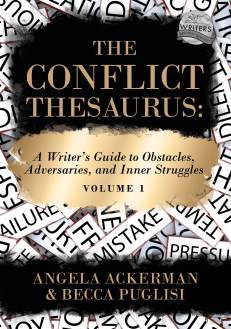

This seems like an excellent time to mention we’re releasing The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles Volume 1 on October 12th!

Want to know more about conflict categories & scenarios you can use in storytelling?

More about The Conflict Thesaurus

Master List of Conflict Scenarios (including sample entries from the book!)

Sign up for an email notification when the book releases

The post Testing Fate: A Closer Look at Person vs. Fate Conflict appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 28, 2021

Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Grandparent and Grandchild

Successful stories are driven by authentic and interesting characters, so it���s important to craft them carefully. But characters don���t usually exist in a vacuum; throughout the course of your story, they���ll live, work, play, and fight with other cast members. Some of those relationships are positive and supportive, pushing the protagonist to positive growth and helping them achieve their goals. Other relationships do exactly the opposite���derailing your character���s confidence and self-worth���or they cause friction and conflict that leads to fallout and disruption. Many relationships hover somewhere in the middle. A balanced story will require a mix of these dynamics.

The purpose of this thesaurus is to encourage you to explore the kinds of relationships that might be good for your story and figure out what each might look like. Think about what a character needs (good and bad), and build a network of connections for him or her that will challenge them, showcase their innermost qualities, and bind readers to their relationship trials and triumphs.

Grandparent and Grandchild

Description:

The grandparent/grandchild relationship is as varied as any familial relationship, running the gamut from intimate to distantly polite to toxic. Many factors will play into this relationship, such as physical distance between the parties, differing ideologies, and the parent’s influence, so it’s important to explore it from every angle to determine what will work best for your characters and story.

Relationship Dynamics

Below are a wide range of dynamics that may accompany this relationship. Use the ideas that suit your story and work best for your characters to bring about and/or resolve the necessary conflict.

Unconditional loved based on family ties

A grandparent who gives the grandchild the freedom to establish their own beliefs and values

A grandparent who backs up the efforts and parenting philosophies of the grandchild���s parents

A grandparent being a listening ear and part of the grandchild’s support system

A grandchild helping and supporting an elderly grandparent on a practical level

A grandparent learning new ideas and skills from their grandchild

A grandchild seeing their grandparent as a source of wisdom and guidance

A grandparent and grandchild who do not know one another well, if at all

A grandparent and grandchild who are cordial and polite but have no deeper relationship

The grandparent being too permissive in an attempt to be the grandchild���s friend��

The grandparent modeling bad behavior that the grandchild may emulate

A grandparent controlling and manipulating the grandchild

A grandchild who manipulates their grandparent to circumvent their parents

Conditional love based on the grandchild���s obedience and achievement

A neglectful or disinterested grandparent

An abusive or cruel grandparent

Challenges That Could Threaten The Status Quo

The grandparent being physically or financially unable to visit their grandchild

The grandchild���s family moving far away

The grandparent falling ill or being diagnosed with a serious medical condition

A new grandchild entering the scene

The grandparent needing to move into an assisted living facility

The grandparent refusing a request for help from the grandchild

The child���s parent being imprisoned, abandoning them, or dying

The grandchild being forced to spend time with the grandparent

Either party revealing a sensitive secret to the other

The grandparent needing to move in with the grandchild���s family

The grandparent losing their spouse

The grandparent not accepting the lifestyle choices of the grandchild

A falling-out between the grandparent and the child’s parent

The grandparent divorcing their spouse or remarrying

The grandchild needing financial help from their grandparent

The grandchild needing to live with the grandparent

The grandparent neglecting their grandchild or putting them in harm���s way

Conflicting Desires that Can Impair the Relationship

One party wanting a different level of communication and interaction than the other

The grandparent wanting custody of the grandchild

The grandchild wanting to live with the grandparent instead of their parents

The grandparent wanting the grandchild to share information about family ongoings

The grandchild wanting the grandparent to advocate for them while the grandparent prefers to stay out of their troubles

The grandparent wanting their estate to be executed differently than the grandchild does

The grandchild wanting all the grandparent���s attention

The grandparent wanting to ignore the preferences of the grandchild���s parents

The grandchild wanting medical care or a living situation that differs from what the grandparent chose

The grandparent wanting greater control over the grandchild���s life

Either party wanting the other party to embrace their views on lifestyle, religion, politics, or other divisive topics

One party wanting to keep a secret hidden

The grandparent wanting a different future than the one the grandchild is planning

Clashing Personality Trait Combinations

Independent and Controlling, Nurturing and Withdrawn, Ambitious and Lazy, Responsible and Scatterbrained, Responsible and Irresponsible, Playful and Humorless, Needy and Independent, Generous and Selfish

Negative Outcomes of Friction

Strained social interactions

Other family members being caught in the middle

Losing a sense of independence and voice

Arguments and fights

Estrangement

Stress and anxiety associated with keeping secrets

Losing the chance at a meaningful familial relationship

Failure to understand one���s heritage and future

Feelings of being misunderstood, unsupported, and rejected

Losing the chance to guide a loved one through life���s challenges

Being unable to separate love from money

Losing the chance to be mentored through difficult times

Fictional��Scenarios That Could Turn These Characters into Allies

The grandparent guiding the child through a challenge (school, friendships, romantic relationships, etc.)

The grandchild being adopted by the grandparent��

The grandparent needing the grandchild to help them with a project

The parties coming together to support or defy another loved one

Embarking on a trip or outing together

Helping one another through tragedy

Discovering a shared problem, such as a health issue or cultural challenge

Ways This Relationship May Lead to Positive Change

A grandparent who was not the best parent having a second chance at their role

The two learning and growing from each other���s perspectives and experiences

Finding satisfaction and purpose through investing time in the relationship

A grandchild learning to accept wisdom and guidance from an older family member

A child feeling valuable and full of potential

Either party learning to compromise

The relationship serving as a bridge for other strained relationships within the family

Themes and Symbols��That Can Be Explored through This Relationship

Coming of age, Death, Endings, Family, Friendship, Health, Hope, Illness, Inflexibility, Innocence, Journeys, Loss, Love

Other Relationship Thesaurus entries can be found here .

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (15 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Grandparent and Grandchild appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 26, 2021

Use Trauma Strategically To Create An Emotional Arc

By Lisa Hall-Wilson

Many authors give their characters past trauma that makes life more difficult and at the very least adds internal conflict. But are you strategic with the kind of trauma you choose���the severity, the onset, the symptoms and coping mechanisms? What���s the character���s emotional arc and how does the trauma shape that arc?

Types Of TraumaTrauma is anything that leaves a person feeling overwhelmed.

That���s it. There���s no threshold of ���bad��� that needs to be reached. We tend to think of trauma as huge horrifying events, such as combat/war, displacement, a natural disaster, car/plane/train accidents, rape, kidnapping, a near-death encounter, etc. These kinds of events change you, sometimes in only the span of minutes.

However, what���s more common is the everyday kind of trauma that every one of us has suffered to varying degrees. Some common examples might be divorce, forced relocation, public ridicule, loss of a loved one (even to natural causes), job loss, relationship loss, betrayal, poor response to a personal disclosure, sibling rivalry, emotional neglect, a health crisis or a sudden medical procedure, etc. This kind of backstory influences characters��� decisions, motivations, priorities, likes and dislikes, prejudices, and blind spots just as much as the big trauma events.

I really love the character Tyrion in the Game of Thrones series (books and TV). Tyrion is shaped by the fact that he has dwarfism. Having dwarfism is not a peripheral detail to differentiate him from the other characters. The specific and unique kinds of trauma he suffered growing up because of his stature influences every future decision and is subtly woven into every emotion he expresses, numbs, and holds back. His past trauma equipped him to survive, even though that same trauma was also a handicap and an anchor. The trauma wasn���t just a detail added to create sympathy in readers for a hard-to-like character.

Strategic Use Of TraumaBefore randomly choosing a trauma from the past, think about who your character is and how this trauma could make their story journey more difficult for them. Get really curious about this.

As an example, let���s take a look at Bilbo Baggins. Bilbo is a perfectly respectable hobbit until a wizard shows up with 13 loud, strong, obstinate, opinionated dwarves. Knowing what sort of challenges are ahead of him, what kind of trauma background could an author give a character like Bilbo that would make solving his story problem even more challenging (and definitely feel impossible)?

Bilbo is a homebody and an introvert, and living with so many boisterous individuals with strong personalities is a challenge. But imagine a Bilbo with a past of abuse that comes out in his adult life as extreme people-pleasing and conflict avoidance? How would this anxiety have made life even more difficult and bring additional challenges during his encounter with Gollum, facing off with Smaug, or negotiating with a walled-up Thorin to honor his promises to the people of Lake Town?

The past trauma you choose to include should be more than emotion-theatre. It should make your character���s journey more difficult and be specific to the journey ahead of them. I know this is hard if you���re a pantser, but it may be something to consider for a rewrite or editing phase.

Trauma Memories Are Often AvoidedPart of being strategic with trauma backstory is knowing when and how much to share. My personal preference is to drip in backstory. What does the reader need to know to make sense of what���s going on right now? It���s often far less than what you think the reader needs. This slow peeling back of emotional layers can increase the tension for readers.

Because the reality is that most people will do almost anything to avoid being reminded of the worst moment of their life. These are not the sorts of things people navel gaze over.

���Trauma comes back as a reaction, not a memory.���

~Bessel Van Der Kolk

Consistent use of coping mechanisms can show a past trauma early on without having to delve into the backstory before it���s necessary. A great example of this are the opening scenes from the movie Sleeping With The Enemy���Laura’s obsessive straightening of cans in cupboards, of adjusting towels on towel rods to precision, etc. It all pointed to this frantic need to appease someone else, someone she was afraid of. The specifics of the trauma weren’t necessary in those opening scenes to create tension.

There have been studies done on young men who suffered abuse by priests as young boys. Those who struggle with anxiety (of any sort) often become gym rats. They work out, they are health nuts, because they don���t ever want to be overpowered again. This obsessive need to be strong, stronger than most everyone else, is the reaction.

So ask yourself: How can you be strategic with the reaction to the emotions your character suppresses or tries to avoid?

Trauma Is Like A Spider���s Web

Trauma is not just something the character thinks about. Emotions are the key to making trauma reactions believable and visceral for readers, so be strategic with specific and unique ways those emotions affect the character’s body. Where do they hold or carry the tension? Do they clench their teeth? Does their neck ache? Do they have stomach problems? Do they have trouble sleeping? Do they startle easily? Do they get angry easily?

The way they carry the past in their body will also affect their behavior and choices. Some people become angry when one of those old emotions are triggered. Some people become compliant and seek to please everyone around them. My point? It���s all connected. One symptom or coping mechanism or trauma memory doesn���t exist in isolation from the character���s thinking, feeling, reacting, and decision-making. Avoid the temptation to use past trauma as emotion-theatre.

You can���t tear a hole in a spider���s web and not create reverberations felt throughout the entire structure. How could you use those reverberations to create more inner or external conflict? Maybe a woman who���s been raped obsessively uses exercise to regain a sense of control. But then she breaks her leg and is stuck on the sofa for two months. There���s a tear in the web. How would removing that coping mechanism affect her thinking, her emotions, her ability to cope with all of it?

PSSSST! Lisa’s got two courses on writing in deep POV that you might want to check out. Writing in Emotional Layers and Deep Point Of View Foundations can help you learn the effects the tools used in deep POV aim to create, so you can use those tools to best serve your story and your voice.

Lisa Hall-WilsonResident Writing Coach

Lisa Hall-WilsonResident Writing Coach If Lisa had a super-power it would be breaking down complicated concepts into digestible practical steps. Lisa loves helping writers ���go deeper��� and create emotional connections with readers using deep point of view! Hang out with Lisa on Facebook at Confident Writers where she talks deep point of view.

Twitter �� Facebook �� Website �� Pinterest

The post Use Trauma Strategically To Create An Emotional Arc appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 24, 2021

How to Nail the Purpose of Your Novel’s Scenes

By Resident Writing Coach Alumni, C. S. Lakin

Ever read a scene in a novel, get to the end, and scratch your head?

Have you ever asked, ���What the heck was the purpose of that scene? Nothing really happened���at least nothing interesting or _____? (important, revealing, tense, or funny ��� you fill in the blank).

It should be obvious that every scene���and let me emphasize every���should have a purpose.

It makes me think of the purposeful scene in the movie Babe in which the stuck-up cat lays out for Babe the pig what his impending fate is and why. Let���s listen in on part of their conversation:

Cat: And they even say that you don’t know what pigs are for.

Babe: What do you mean, what pigs are for?

Cat: You know, why pigs are here?

Babe: Why are any of us here?

Cat: Well, the cows are here to be milked; the dogs are here to help the Boss���s husband with the sheep; and I���m here to be beautiful and affectionate to the Boss …

Babe: Yes?

Cat: Ah, the fact is, pigs don’t have a purpose. Just like ducks don’t have a purpose.

Babe: Uh, I .. I don’t ��� uh …

Cat: Oh, all right. For your own sake, I’ll be blunt. Why do the Bosses keep ducks? To eat them. So why do the Bosses keep a pig? The fact is that animals that don���t seem to have a purpose really do have a purpose. The Bosses have to eat. It���s probably the most noble purpose of all, when you come to think about it.

Babe: They ��� eat ��� pigs?

Cat: Pork, they call it. Or bacon. They only call them pigs when they’re alive.

Babe : But, uh, I’m a sheep pig.

Cat : [giggles] The Boss���s husband’s just playing a little game with you. Believe me, sooner or later, every pig gets eaten. That’s the way the world works. Oh … I haven’t upset you, have I?

We aren���t left guessing why this scene is purposeful���it���s meant to give Babe doubts about Farmer Hoggett, whom he believes is a true friend with Babe���s best interest at heart. It���s meant to propel Babe into his dark night of the soul moment, which threatens to destroy his heart���s desire to be the best sheep-pig in the world (though, it���s likely he���s the only one in existence). Which would sabotage the plot goal���participating in and winning the sheep trials. It���s meant to put a rift of suspicion between the two main characters, adding tension and raising the stakes.

All this and more in this one scene. You see���scenes can accomplish many things, but they must primarily accomplish one thing ���

Propelling the plot forward toward the dramatic climax.You might argue: well, that���s an important scene, so of course it has a purpose.

I would answer: in a great story, every scene has a purpose. Not only that���every single word and action, even the mention of a gesture or expression, serves a purpose.

Just that truth should get you fine-combing through every line in your manuscript to ensure, yes, it all serves a purpose.

So ��� now that we got that out of the way, let���s deal with the even more important purpose of this post: to explain how to nail the purpose of your novel.

Here���s the kind of thing I see in many of the hundreds of manuscripts I critique every year:

I read the synopsis of the story, and it���s a suspense thriller about a woman whose expensive, rare ancient necklace has been stolen to use in a dark ritual. In her attempt to get it back, she���s abducted and soon to be sacrificed in that ritual wearing that necklace because, of course, her family line has some inherent power that the nemesis covets and by killing her he will absorb that power. Her boyfriend/treasure hunter/former Navy Seal is on the tail of the bad guy hell-bent on rescuing her, promising an exciting nail-biting confrontation at the climax.

Great premise, I think. Lots of potential for high action and drama, high stakes, an emotional ride, tense climax. Perfect premise for the genre. Readers will love it.

Writing ability aside, this promises to be a well-structure story with purposeful scenes ��� because the writer has laid out all the significant plot elements in the synopsis.

Then ��� I start reading the manuscript.

Scene after scene goes by ��� and I���m wondering when the author will mention the necklace. By the midpoint, I���ve finally seen the protagonist at an event where her necklace is on display with other ancient artifacts. But nothing���s really happened in the story so far.

In fact ��� all the opening scenes are lighthearted, about her boyfriend and their dinner dates. Filled with lots of small talk���boring, predictable dialogue���with no tension, no inner or outer conflict, no mystery, nothing at stake.

I���m sure you can see what���s wrong here.

First and foremost, the writer hasn���t done her genre homework. The book sounds more like a rom-com (romantic comedy) sans the ���com.��� That���s one absolute essential to nailing the purpose of your novel.

Readers have a purpose when they sit down and open a book���they have expectations of enjoying a novel they think is in the genre it claims to be in. How upsetting when that novel fails to deliver what���s rightly expected.

For every scene in your novel to work, it has to fit genre expectations. Don���t dismiss that.

The second way you nail the purpose of your novel is to build it to support your premise.

What���s a premise? It���s a situation the presupposes the need for action. In other words: something���s the matter, and someone needs to deal with it. Yes, that���s your protagonist. And her goal. Which gets resolved at the climax, and then the book ends shortly after.

Uninformed or inexperienced writers think that the first chunk of their novel needs to explain and set up background on the characters, details about their world, show how they interact with others ��� and, eventually, maybe by the midpoint, start bringing in the situation the premise hinges on.

All that stuff mentioned above���that���s what the first scene���the setup scene���needs to accomplish. And shortly after that should follow what���s called the inciting incident (or disturbance or opportunity). That incident is what showcases the premise.

I would expect in that example I gave that by chapter 2 the necklace has already been stolen and the stakes are high. By chapter 3 I���d look for the character to be in danger and shortly abducted after that.

It���s really quite simple if you know basic story structure. And therein lies the problem for many writers.

They don���t know story structure. And, in almost every case, that equates to novel failure.

The good news is learning story structure is easy. There are foundational scenes���key scenes���that the entire story is built on. You can start with those���what I call the 10 Key Scenes���and learn where they go and what they must accomplish. From there you add in more scenes (I use a layering method that works every time, and it���s laid out in Layer Your Novel.)

Indeed, the purpose of your novel, ultimately, is to entertain your readers���whether you intend to make them bite off all their nails, jump for joy, cry their heart out, or all three.

But to accomplish that purpose, you have to have a strong, enticing premise that fits a specific genre (and has all the genre markers), with every scene ���advancing the plot.���

Advancing how, in what way?

Purposefully���to play out the premise you���ve come up with. Amid rising high stakes and conflict, tension and obstacles, twists and setbacks, and all those glorious things readers love in the novels they read.

Every scene needs to end with a punch, a high moment that indicates how the character has changed in the scene (yes, in every scene) and hinting at what���s at stake (yes, in every scene). If a scene has nothing at stake, no high moment punched home at the end, nothing new revealed, then ��� it has no purpose.

And we know what happens to things that don���t serve a purpose���they meet their doom.

So be sure to study genre and story structure. Don���t waste your time writing purposeless scenes. Craft a great premise and make every word count!

If you���re ready to take 8 weeks to learn everything you need to know to write a great novel, enroll in C. S. Lakin���s upcoming course 8 Weeks to Writing a Commercially Successful Novel. Packed with a year���s worth of content (more than 10 hours of lecture and dozens of scenes from best-selling novels analyzed, plus handouts and worksheets galore), fiction writers of any level will learn the secrets of bestsellerdom.

And if you���ve written at least one novel, check out her master class 12 Weeks to Nailing Your 10 Key Scenes.

Both courses are open for enrollment and start September 6th.

C. S. Lakin is a writing coach, workshop instructor, and award-winning author of 30+ books and blogger at Live Write Thrive. Her Writer���s Toolbox series of books teach the craft of fiction, and her online video courses at Writing for Life Workshops have helped more than a thousand writers. She also works as a book copyeditor and does more than 200 critiques a year for writers, agents, and publishers in six continents (she���s still waiting for someone in Antarctica to hire her ���).

The post How to Nail the Purpose of Your Novel’s Scenes appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 21, 2021

Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Therapist and Patient

Successful stories are driven by authentic and interesting characters, so it���s important to craft them carefully. But characters don���t usually exist in a vacuum; throughout the course of your story, they���ll live, work, play, and fight with other cast members. Some of those relationships are positive and supportive, pushing the protagonist to positive growth and helping them achieve their goals. Other relationships do exactly the opposite���derailing your character���s confidence and self-worth���or they cause friction and conflict that leads to fallout and disruption. Many relationships hover somewhere in the middle. A balanced story will require a mix of these dynamics.

The purpose of this thesaurus is to encourage you to explore the kinds of relationships that might be good for your story and figure out what each might look like. Think about what a character needs (good and bad), and build a network of connections for him or her that will challenge them, showcase their innermost qualities, and bind readers to their relationship trials and triumphs.

Therapist and Patient

Description:

A patient visits a therapist to receive treatment and rehabilitation in support of their mental and emotional wellbeing. A therapist’s guidance helps the patient identify their emotions, cope with daily challenges, reduce symptoms of mental illness, and make life choices.

The term ���therapist��� is a broad one that encompasses social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, life coaches, and more. The label also applies to counselors who deal with marital, family, and substance abuse issues, among others.

Relationship Dynamics

Below are a wide range of dynamics that may accompany this relationship. Use the ideas that suit your story and work best for your characters to bring about and/or resolve the necessary conflict.

A therapist and patient working together willingly to solve a problem

A therapist working with a reluctant patient, such as a teen whose parent is making them attend sessions or an addict partaking in court-enforced rehab

A patient seeing an overworked or incompetent therapist who isn’t really helping

Two willing participants who just aren’t a good fit for each other

A once-willing patient backsliding into destructive habits and no longer being honest with their therapist

A long-term patient becoming frustrated with their lack of progress and pulling away from the therapist

A therapist becoming too emotionally involved in a patient’s situation

A needy patient demanding too much time or attention from their therapist

Challenges That Could Threaten The Status Quo

The therapist quitting their practice

The patient or therapist relocating��

Insurance changing for either the patient or the therapist���s practice

Either party developing feelings beyond the professional relationship

The therapist gossiping about the patient

Either party accusing the other of inappropriate conduct

The patient suffering a severe setback (a relapse, family tragedy, job loss, breakup, etc.)

Someone the patient knows receiving care from the same therapist

The patient refusing to participate in a session

The therapist giving the patient bad guidance or wrongly diagnosing them

The patient not following through on their appointments, promises, or the advice of the therapist

The patient coming off of prescribed medication for mental health reasons

The patient���s situation stirring up painful memories for the therapist

The patient giving the therapist a bad review

The patient failing to pay for services

The therapist not having the skills, knowledge, or experience to help the patient

The patient lying to the therapist

The therapist exerting too much control over the patient

Conflicting Desires that Can Impair the Relationship

The patient wanting to stop therapy before the therapist believes they are ready

The therapist wanting to put the patient on medication, and the patient resists

Either party wanting a different amount of time together than the other party

Either party wanting to bring a third party into the sessions, while the other does not

The therapist wanting to refer the patient to someone else

The patient wanting more access to and communication with the therapist

The therapist wanting information the patient is not yet ready to reveal

The patient wanting to finish therapy in order to meet an external requirement, while the therapist wants them to accept help

The patient wanting to keep secrets from the therapist

Either party wanting control

Either party wanting a personal relationship

The patient wanting the therapist to lie on their behalf

The patient wanting to maintain behaviors, believing they can self-monitor them

The patient expecting an unrealistic outcome based on what is possible through therapy

Clashing Personality Trait Combinations

Persuasive and Gullible, Dishonest and Honorable, Courteous and Disrespectful, Judgmental and Oversensitive, Independent and Needy, Ambitious and Lazy, Discreet and Gossipy, Confrontational and Timid, Nurturing and Withdrawn

Negative Outcomes of Friction

The patient quitting therapy

The therapist refusing to see the patient

The patient becoming jaded and cynical about therapy

Decreased trust

The therapist experiencing a crisis of self-doubt from being unable to help

Passive-aggressive behaviors

Secret keeping, which increases tension and anxiety

The patient feeling powerless to change their circumstances

The therapist worsening the patient’s mental health instead of improving it

Paranoia and worry

Either party being overwhelmed by the scope of the issues

Fictional��Scenarios That Could Turn These Characters into Allies

Sharing a common experience in their personal lives

Coming together to meet the needs of a third party (a child, a spouse with medical concerns, etc.)

The two parties reaching a financial arrangement that suits them both

Showing a united front for an official entity (a court of law, mediation, etc.)

Cooperating and compromising to meet the patient���s needs in an unconventional way

The therapist leading the patient to a significant breakthrough

The patient agreeing to leave an abusive situation with the help of the therapist

A reluctant patient seeing the need for therapy and fully committing to the process

The therapist helping the patient reach a milestone or goal

Ways This Relationship May Lead to Positive Change

A patient learning that not all relationships are untrustworthy

A patient feeling validated and understood

Both parties learning to compromise

Either party feeling empowered by the success of the relationship

The patient reaching a significant goal with the help of the therapist

Learning to respect one another���s viewpoints

The therapist learning to think outside the box to come up with new treatment methods

The patient identifying a longstanding issue and being able to deal with it

Lessons learned in therapy helping the patient succeed in numerous areas of life

Themes and Symbols��That Can Be Explored through This Relationship

A fall from grace, Alienation, A quest for knowledge, Beginnings, Deception, Depression, Disorder, Freedom, Friendship, Health, Hope, Illness, Innocence, Journeys, Loss, Mystery, Obstacles, Perseverance, Recognition, Refuge, Sacrifice, Stagnation, Suffering, Teamwork, Transformation, Vulnerability

Other Relationship Thesaurus entries can be found here .

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (15 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Relationship Thesaurus Entry: Therapist and Patient appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 18, 2021

The Storyteller’s Roadmap: Your Ultimate Guide to Planning, Writing, and Revising a Book

By now, most of you know that Becca and I are pretty nerdy when it comes to writing. We’ve spent over a dozen years studying story craft and psychology, and how to blend the two to create powerful stories that will draw readers in on an emotional level. We���ve penned millions of words on writing, taught internationally, and helped creatives all over the world through our books, tools, and resources.

But one thing we���ve never done is create a complete plan for writing a book…until now.

But one thing we���ve never done is create a complete plan for writing a book…until now.The Storyteller���s Roadmap is a user friendly, at-your-own-pace method to get you from that first word, to done.

We guide you through the important pieces of a story, helping you brainstorm and plan a great concept and plot, compelling characters, and a world that your readers won���t want to leave.

We stay with you as you write, helping you with strategies to stay focused, creative, and on task. And all those common writing derailments like writer���s block, self-doubt, procrastination, and getting lost in the middle of your novel? We show you how to get past these so the words continue to flow.

Of course, once the first draft is written, the real work begins. Revision can be where a lot of writers lose their passion for the story because they struggle to know exactly how to bring their best writing to the page. We’ve broken down the revision process into manageable pieces, so you have a path through the rounds of editing, feedback, and polishing to come.

As you follow the roadmap, we point you to tools and resources that can make the job much easier, saving you time and frustration.We also share hard-won advice, articles, and strategies, filling any gaps in your knowledge and shortening the learning curve to writing a great novel.

Hiring a story coach can be very expensive, and out of reach for many.The Storyteller’s Roadmap is like having Becca and me with you at every step, and is designed to build on your knowledge so your writing becomes stronger and stronger.

So where can you access this self-guided route to a publish-ready manuscript? At our sister site, One Stop for Writers. Wherever you are in the process, planning, writing, or revising, find the roadmap section that suits you best. And then…write!

The post The Storyteller’s Roadmap: Your Ultimate Guide to Planning, Writing, and Revising a Book appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 17, 2021

Breaking Free

By Christina Delay

Freedom is a contradictory word, don���t you think? The official definition of freedom is the power or right to act, speak, or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint. However, follow that to its extreme and chaos reigns.

But that���s the dream of every author, right? To be free to write on our own schedule, without the hindrance of other obligations. We want our book sales or family life or work schedule to provide us this freedom so we may be the best author we can be. But what happens when we get exactly what we want?

The patooties are heading back to school for the first time in seventeen months, and I am nose-to-nose with this concept of freedom, experiencing its contradictions in all its forms:

Fear of the unknownExcitement for an actual work dayTrepidation about what to do with uninterrupted hours (or, let���s be real here, minutes)Uncertainty about the right path forwardElation about having a few quiet hours in the house to write and to workDoubt I can meet my writing goals and deadlines again, as it has been so very long….I don���t feel very free.

With the world finding a new normal, are you experiencing something similar? Whether it be back-to-school, back-to-in-office-work, or simply the end of summer approaching, it���s not surprising if we find ourselves wrestling with conflicting emotions about the next season of our life.

Ronald Reagan says we need order to have freedom.

���There can be no freedom without order, and there is no order without virtue. ���

The musical Hamilton says our freedom can never be taken away.

���Raise a glass to freedom, Something they can never take away.���

Turns out, feeling free is different from freedom. Breaking it down further, I believe that in order to feel free and experience true freedom, we must first break free…

From ExpectationsExpectations are a sticky bog. Whether they be our own expectations for ourselves, others’ expectations for us, or even our expectations of others, when we start making decisions based on expectations, and our attitude and mood are affected by expectations, we lose our freedom. We are no longer able to feel free.

What expectations are you or others placing on your creative life?

A golden first draftTo make a story fit into a specific genreTo meet every deadline (self-imposed or contractual), regardless of what is going on in your personal lifeMore salesFive star reviewsThis book must do better than the last bookThis book must be better than the last bookReader feedback, suggestions, wish listMust engage your community on social mediaWrite X amount of words or write for X amount of time every dayCan you feel the pressure building? Just writing that list made my breathing go shallow.

Now take a moment and imagine…how would it feel to let all of that go?

What impact would it have on your creativity if you approached it with zero expectations, if you allowed yourself to simply enjoy the moments in which you have to write?

I bet it���d be pretty freeing.

From Old HabitsI don���t know about you, but I have developed some…let���s frame it as not helpful…habits over the past year.

Now is a good time to assess what lifestyle changes we���ve accepted that may no longer be beneficial to what we actually want for ourselves.

What do you want? What habits are holding you back from getting there?

As with all change, baby steps that are achievable, measurable, and realistic are key. Can you commit to taking a brainstorm walk once a week? How about going to bed 30 minutes earlier? Or meal plan once a week?

Being free to be our best creative selves starts with self-care. Self-care is not selfish. It is essential.

There is freedom in understanding what it is we want for ourselves. Now���s the time to take the steps away from unhelpful habits and move toward affirming rituals that lead us further down the path we���ve chosen.

From Upheaval…or rather, the anxiety that upheaval can cause.

And, as I���m sure you well know, anxiety is a huge drag on creativity. 2020 was a huge upheaval year. 2021 continues to be a huge upheaval year. Throw in any personal or family changes and, well…anxiety is a fairly common emotion that���s been floating around.

Our brains are wired to avoid change. Why? Change means we���re introducing something unknown into our safe zone, triggering our brains to think we���re no longer safe.

When we begin to understand the scientific why of our reactions to change or new information, we gain the ability to better handle the anxiety that comes hand-in-hand with upheaval. Knowing that anxiety is normal when something new is introduced into our life makes it easier to breathe through it, to know that this too will pass.

It is okay if your creativity suffers during a time of upheaval. It is normal.

So break free from the guilt surrounding not being able to be your most creative self during a time of upheaval. Let it go, give yourself grace, and I bet you���ll quickly find yourself feeling free.

Breaking Free

I wish I had a magic button or a code word that could open a heart and mind to accepting freedom without hesitation or restraint. But I don���t.

What I do have is persistence and faith. Persistence to keep trying, to keep doing a little better each day in letting go of expectations, accepting change, and breathing through anxiety. Faith that despite the uncertainty of the immediate future, I will choose to do what���s best for me, my creativity, and my family and friends.

Easier said than done, I know. So here are some practical tips on how to move into a new season with acceptance, grace, and hopefully, some creative productivity.

Find a quiet time in the mornings to meditate, pray, or journal about your creative vision for this new season. Even five minutes will allow you a more centered start to your day.Reach out, talk to a friend. Connection with our trusted circle of loved ones is healing, and allows for us to navigate change with a cheer squad in the background.Accept that your creative work is important and necessary.Set small, achievable goals, rather than big, insurmountable deadlines.Remember to breathe.There can be no freedom without order…and that order comes from our inner selves being at peace and able to flexibly move through change.

So raise a glass to freedom. And then get back to writing.

Christina DelayResident Writing Coach

Christina DelayResident Writing CoachChristina is the hostess of Cruising Writers and an award-winning psychological suspense author. She also writes award-winning supernatural suspense under the name Kris Faryn. You can find Kris at: Bookbub �� Facebook �� Amazon �� Instagram.

The post Breaking Free appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 13, 2021

Describing a Character’s Emotions: Problems and Solutions

Characters are the heart of a story, but what really draws readers in is their emotions. Only…showing them isn’t always easy, is it?

Like us in the real world, characters will struggle. Life is never all cherries and diamonds; in fact, it’s our writerly job to make sure reality fish-slaps our characters with painful life lessons! Big or small, these psychologically difficult moments will cause them to retreat and protect themselves emotionally, believing if they do so, it will prevent them from feeling exposed and hurt in the future.

And while we know “shielding” behavior is psychologically sound (we do it, too) and it means our characters will try to hide it when they feel vulnerable, this causes a real problem at the keyboard end of things. Why? Because no matter how hard a character is trying to hide or hold back their emotions, we writers must still show them. For readers to connect, they have to be part of that emotional experience.

(Reason #63027 why writing is HARD, right?)

A wounding event also causes emotional sensitivities to form, meaning your character may overreact when certain feelings draw near. A man who was mugged may verbally lash out at a stranger who touches his arm to ask for directions. A teenager may be unable to answer an easy question in class after forgetting the words to a song during her school’s talent show.

Not only can our characters be easily be triggered and give into their flight, flight, and freeze instincts, they may also project feelings onto others, deny them, become self-destructive, act out, or a host of other things…all of which we will need to show in a way that fits the character’s personality, comfort zone, and circumstances. It’s a tall order.

Three Tips to Show Emotion Well…Hidden or Not Know your character. So crucial. It’s the key to everything, so when you have a second, read this post to find out why. (No point reinventing the wheel.)Understand the character’s emotional range. Their “baseline” comfort zone & preferences are tied to their personality and will guide you to emotional expressiveness that will align with who they are, meaning what they do, say, and experience will ring true to readers.

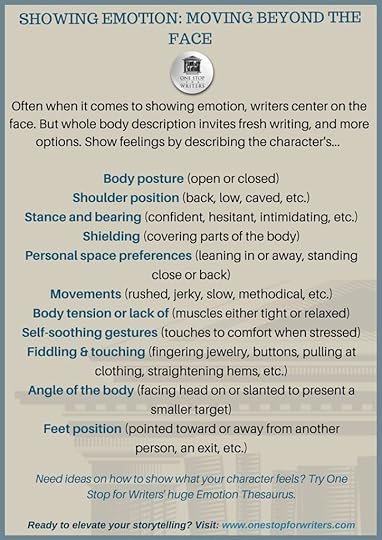

To avoid telling, think about the many unique ways emotion can be expressed. Writers can sometimes rely too much on expressions or gestures, so think past that steely glare or stomping foot. These tip sheets are gold:

Click here to download these tip sheets (and many more!)

Another challenge when it comes to showing readers what our characters feel is that emotions rarely show up alone. Most situations or events generate a mix of feelings, some of which may conflict with one another. For example, a character may feel…

Anxiety over what comes next while feeling relieved at being spared a worse fateHappiness at an outcome yet being worried about what loved ones will sayElation at winning but beneath it, insecurity over whether it was truly deservedGratitude at surviving along with the crushing guilt that comes with doing so when others were not so luckyI think we can all think of moments like these. A surge of emotion hits, and we laugh through our tears, collapse in jubilation, or even attack a loved one for delivering news that nearly destroys us. While it takes a greater effort to show multiple and/or conflicting emotions, experiencing more than one thing at once is true-to-life, and so can make these story moments more genuine and gripping.

Three Tips for Showing Multiple or Conflicting EmotionsWith multiple emotions, show them in order. For example, if a sibling were to jump out and scare the protagonist as she’s heading down the hall toward her room, she’ll feel fear, then relief, then mock-anger. If you showed this, it might go like this: jumping back with a shriek, sagging against the wall, and then charging her sibling and shoving him to the ground.If you need to, slow things down a touch. Focus description on what is causing the character to feel a specific emotion (stimulus), and then show what they do because of it (reaction). This helps readers see an event, person, situation, etc. is affecting a character and directing their behavior, action, and choices.

If the emotions are complicated or in conflict, you can also use a carefully placed thought (if it’s a POV character) or dialogue (if not). The important thing is to show the context of what’s happening. This doesn’t mean to fall into the trap of telling, rather to use realistic thoughts, questions, or comments that indicate something is influencing your character’s emotions (and therefore explains their actions).

Showing compelling emotion can be challenging, but thankfully there are many, many terrific ways to do it well. With effort, using a mix of expressions, behaviors, dialogue, thoughts, visceral sensations, vocal cues (and more!) will convey our character’s personal moments authentically, drawing readers in.

Need More Help?

The Emotion Thesaurus provides a starting point for emotion, providing lists of ideas on how it can be shown, which writers then adapt and tailor to each character’s unique personality and way of expressing. This guide is packed with advice on how to show emotion that draws readers into the character’s experience. It’s helped hundreds of thousands of writers improve their emotional showing, and if you struggle in this area, maybe it can help you, too.

I should mention that for the month of August, the EXPANDED edition (130 Emotions) is a $2.99 Kindle Deal at Amazon.com and Amazon.ca. It’s also a Monthly Kindle Deal at Amazon.in (���129.00 ). So if you don’t have this book (or you currently have the first edition containing 75 emotions) now’s a good time to save. (Note: affiliate links)

I hope these tips help. Happy writing to all!

The post Describing a Character’s Emotions: Problems and Solutions appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 11, 2021

The Conflict Thesaurus Writing Guide Is Coming

Each year we look forward to this post, the one where we get to spill the beans and introduce to you the next book in our thesaurus series. This one we are so excited about, because no matter what genre, medium, and age group you write for, mastering conflict is a must. And this book is going to help you do just that.

But first…THE COVER!

But first…THE COVER!Isn’t she pretty?

We figured it was time to go for gold, because, well, this book is a goldmine of conflict scenarios that will challenge your character inside and out! Here’s the back jacket…

THE CONFLICT THESAURUS, VOLUME 1:A Writer’s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles

Every story starts with a character motivated by a need and a goal that can resolve it. Whether their objective is to find a life partner, bring a killer to justice, overthrow a cruel regime, or something else, conflict transforms a story premise into something fresh. Physical obstacles, adversaries, moral dilemmas, deep-seated doubts and personal struggles���these not only block a character���s external progress, they become a personal gateway for internal growth. The right conflict will challenge characters as they traverse their arc, build tension and high stakes, and most importantly, keep readers emotionally invested from beginning to end.

CHOOSE MEANINGFUL CONFLICT TO FIT YOUR CHARACTER AND STORYInside The Conflict Thesaurus, you���ll find:

A myriad of conflict options in the form of relationship friction, failures and mistakes, moral dilemmas and temptations, pressure and ticking clocks, and no-win scenariosA dive into each circumstance to map out possible minor-to-disastrous complications and fallout, internal struggles, and the stressful impacts on a character���s basic human needsGuidance on using conflict to influence your protagonist’s character arc through opportunities for failure and successMaster class instruction on internal conflict: what it is, why it’s important, and how to incorporate it at the scene and story levelThe role conflict plays in generating high stakes that are personally significant to the character, upping the tension for readersA breakdown of the various adversaries your character might encounter along the wayDon’t give your character a break. Keep the hits coming with a variety of obstacles that will force them to work harder to get what they want. With 110 entries in a user-friendly format, The Conflict Thesaurus is the guide you need to write intense and satisfying fiction readers won���t forget.

Volume 1… Does that mean what I think it does?

Volume 1… Does that mean what I think it does? Yes! There will be two volumes. The second will contain even more advice on writing conflict and offer more conflict scenarios, giving you endless way to challenge your characters. Look for Volume 2 releasing in 2022.

Will there be a preorder?Sorry, no. We’ve tried a preorder in the past, but a certain online store made a mess of it (costing us hundreds of sales), so we’re not eager to try again. Our apologies. But you can get a notification the instant the book is available. Just add your email here!

Can I get an ARC of the Conflict Thesaurus?Every book launch we give out 50 Arcs, and unfortunately these have already been distributed. We’re sorry! But we hope you will review this guide when it’s out, and we’d be honored to have you on our Street Team if you’d like to be involved. (See below)

Will you have a Street Team? Can I help?

Will you have a Street Team? Can I help? Yes, yes, and YES! If you would like to be part of our Street Team, you can sign up here. To make this a success, we need helpers in many areas and your support is always appreciated so much. Plus, you get a front row seat to managing a Street Team and running a launch, which you can apply to your own book launches!

Can I access The Conflict Thesaurus at One Stop for Writers?Yes, in September. We always add all thesauruses to One Stop for Writers where they Borg into the largest descriptive database found anywhere.

Did we miss a question? If so, please ask and we’ll be happy to answer!We hope you are as excited for this book as we are! Two months…hurry up and get here, October 12th!

~ Becca & Angela

The post The Conflict Thesaurus Writing Guide Is Coming appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 10, 2021

Don’t Let Excess Baggage Bring Down Your Character’s Plane

By Marissa Graff

We���ve all heard that characters need backstory, and in particular, an emotional wound that they���re carrying around when we meet them on page one. (As an aside, if you haven���t checked out Angela and Becca���s Emotional Wound Thesaurus, you���re missing out. It identifies and explores just about every major wound a character may have from life before your novel starts.)

But what happens when that wound is murky because you haven���t written out the origin scene that gave birth to it? Or, as I see even more commonly in client manuscripts, you have more than one major emotional wound for your protagonist? Giving a character a primary emotional wound is a must. But giving them excess baggage can start to sound like a stereotypical country song. It���s not uncommon that I edit manuscripts where excess baggage is wreaking havoc on both the written story and the reader���s ability to connect with it.

Consider a character who is hiding who they truly are from their parents and they are struggling with addiction and they lost a sibling and they were the victim of a crime. This type of complexity may seem like a good idea. Who doesn���t want lots of conflict, right?

But what winds up happening in a story that starts off this way is that your reader doesn���t know where to look because bags are everywhere. And perhaps worse, there���s nowhere to go in the manuscript in terms of rising tension, rising stakes, and rising action. As a result, the reader is overwhelmed by all the problems your character already has, and they don���t have a clear idea of the misbelief the character needs to let go of by the time the climax rolls around. In the same way games oftentimes have one objective, the reader seeks a sense of the character���s internal objective in order to gauge success or failure come the end of the book. They need to know how this game, otherwise known as your story, is played.

An analogy I use often with editing clients when describing what an opening must function like is the ski jump. The emotional arc ���rails��� you build in scene one will set up the trajectory for the rest of the novel, long after your character has taken off. If your character has a past loaded like that country song, the ski jump won���t create a strong, clear path for either your character or your reader. Instead, the beginning will feel more like a complicated freeway interchange, and you���ll have failed to give the reader the directions that point them toward where to go.

By employing one major emotional wound at your story���s onset, you ensure that the character and the reader engage in a smooth emotional trajectory because you���ve given them directed rails. Yes, complications will be born out of the primary wound as your story plays out. For example, having someone die on your watch might lead to depression or fear of trusting one���s self, which might lead to broken relationships and decreased risk-taking. But trust yourself and your story to carry those obstacles out within your story. As the obstacles build up and things become more and more complicated, the stakes will rise, as will tension. This is the arc you want for your story as it moves along, not when it starts. If the character is carrying excess baggage when we first meet them, there are very few places for them or your story to go.

Challenge yourself to identify the one primary emotional wound your character has in the very first scene. If you have more than one wound, how might you narrow down your character���s backstory so that it creates those strong, directed ski jump rails that will keep the rest of your story on track? One option is One Stop for Writers’ Character Builder, which is great for helping you zero in on just one primary wounding event.

Consider how that wound might lead to secondary difficulties throughout the course of your novel and think about how you might plot those as complications. Above all, give yourself the clarity in knowing the emotional need your character has that your story sets out to fulfill.

Marissa Graff

Marissa GraffResident Writing Coach

Marissa has been a freelance editor and reader for literary agent Sarah Davies at Greenhouse Literary Agency for over five years. In conjunction with Angelella Editorial, she offers developmental editing, author coaching, and more. Marissa feels if she���s done her job well, a client should probably never need her help again because she���s given them a crash-course MFA via deep editorial support and/or coaching. Website | Twitter | Instagram | Facebook

The post Don’t Let Excess Baggage Bring Down Your Character’s Plane appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1014 followers