Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 54

March 1, 2022

Best Practices for Working with an Independent Editor

By Lisa Poisso

Most writers have read the wide-eyed articles from newly-agented writers detailing the pressure of revising and returning edits on a tight schedule and working with an assigned editor. But what if you���re the one hiring the editor? By their nature as entrepreneurs, every independent editor���s business practices vary. Ask your editor about these common expectations and practices before agreeing to any work.

Before Your Edit1. Agreements about the business details of your project protect you both. An agreement needn���t be a formal printed contract signed in person; an email constitutes a legal agreement. The agreement should define the scope of work, start and finish dates and other relevant deadlines, total cost and payment schedule, and a clear explanation of what happens if either party cancels or breaches the agreement.

2. New writers often mistakenly believe they need a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) to protect their material. Your work is legally copyrighted the moment you commit it to print, making NDAs cumbersome, unnecessary, and often a sign of professional mistrust.

3. Most editors require a deposit to get your book on their calendar, customarily ranging from a flat fee of $100 or more to the first half of the total fee. You can expect to pay your total editing bill in full before the editor releases the edited manuscript.

4. If you can���t or don���t want to use your editor���s preferred payment method, aren���t located in the same country as they are, or prefer a slow payment method like personal checks, ask if your choice will create any issues. Allow enough time to process payments without holding up the project.

5. Missing your editing date by even a day or two could leave your manuscript without time to fit into its scheduled slot, if the deadline is tight or your editor is busy. Communicate as soon as you suspect you may have a problem hitting your scheduled editing date.

6. The time it takes to edit a manuscript varies widely, depending on your manuscript���s needs, the type of editing, and the editor���s schedule and work practices. Developmental editing usually takes the longest. Line editing is slower than copyediting, and proofreading is the fastest editing service.

If there were such a thing as a typical editing rate among all these levels of service, it might run from 20,000 to 35,000 words per week. You get what you pay for. If all the editor has time for is a breakneck race through the manuscript, that���s precisely what you���ll get.

Don���t try to reverse-engineer what you think an editor���s editing rate should be based on words or pages per hour. Manuscript speed doesn���t account for writing an editorial report or letter; creating a style sheet; formatting and preparing the file; running automated software and macros to check mechanics, formatting, and style; an initial read-through; a follow-up read-through; or book mapping and structural analysis. If there���s no time for these (or if your editor prices the edit without them), you���ll be missing many aspects of a thorough professional edit.

7. Submitting a manuscript that���s as error-free as possible allows your editor to spend their time on elements that require professional skill and judgment. If the writing needs extensive spelling, grammar, and punctuation cleanup, those things are exactly where the editor will spend their time. Leaving messes for the editor to clean up costs money���your money. Clean manuscripts give editors elbow room to help you elevate your story and writing.

8. Don���t jump the gun with fancy formatting or graphics. It���s not time for your manuscript to look like a book yet. Standard manuscript format���12-point double-spaced Times New Roman, one-inch margins, first-line paragraph indents instead of tabs, one space (not two) between sentences, and no line space between paragraphs���lets your editor get right to work.

9. Although most editors spot-check facts and look for obvious errors (mostly for narrative and internal consistency), factual accuracy���including science, geography, history, and foreign languages���is your responsibility as the author.

During Your Edit10. Some editors consider work complete when they return the edited manuscript to you. This is typical for edits designed to inspire revision and new writing, such as developmental or line edits. Other editors ask that you review and approve or revise their edits and return the manuscript for final adjustments; this is more typical for polishing edits like copyediting or proofreading. These editors will review some or all of your changes; the first sort consider that a new round of editing. Neither way is wrong or superior. Included follow-up rounds generally mean higher rates; many editors who don���t include follow-up rounds offer deep discounts for additional rounds. Ask your editor what���s included.

11. Especially early in your writing career, your manuscript could need multiple rounds of the same type of editing. If a developmental edit leads to significant changes, for example, you could need a second round after revisions. Don���t let this possibility take you by surprise.

12. Expect to work using Microsoft Word and tracked changes. Most editors use Word because it permits the use of editorial tools that increase the accuracy and quality of the edit, a benefit you very much want for your manuscript. Agents, editors, and other publishing professionals will also expect to receive your manuscript as a Word file, not as a PDF or ���compatible��� file. Word and tracked changes look intimidating but aren���t difficult to learn, and working with them is part of a writer���s baseline skills.

13. You may not hear much from your editor while your edit is in progress, or they may contact you with various questions. Both are normal. Editing isn���t a sequential process that starts with chapter one and finishes at ���The End.��� Editors work in layers. There���s often not much to say about an edit in progress beyond ���Yep, still working.���

14. For anything but proofreading, edits are the beginning of the revision process, not the end. Reviewing a copyedit is relatively straightforward, but line and developmental edits are designed to steer you toward deeper, better writing. It���s up to you to follow through with the work.

After Your Edit[image error]15. Editing is a subjective process, and you���re free not to take every edit and recommendation. It���s your book and your vision. Most editors include follow-up time to review points of confusion or disagreement. Disagreeing with the substance of the feedback, however, does not entitle you to a discount or refund.

16. A full-length edit can generate hundreds of comments and tens of thousands of edits. Considering this scope, the final manuscript will inevitably contain some residual errors. You can minimize these by starting with a manuscript as clean as you can possibly manage and finishing with a professional proofread.

17. Just as you wouldn���t want your editor to discuss or share your manuscript with others, it���s unprofessional to share your edits online or kvetch about the specifics with other writers or editors. The edited final product is yours to do with as you wish, but the edits, comments, and editorial feedback themselves are intended for you alone.

18. If you find yourself rejecting most of the edits and suggestions in your edit, you may have hired the wrong editor for the job or pushed for a level of editing your manuscript wasn���t ready for. More often, you simply need some emotional distance from the feedback. Putting away a difficult edit for a while can help you regain objectivity.

19. American authors, don���t file a 1099-MISC for editing fees if you paid using a service such as PayPal. Payments made with a credit card or payment card and certain other types of payments, including third-party network transactions, must be reported on Form 1099-K by the payment settlement entity under section 6050W and are not subject to reporting on Form 1099-MISC.��

20. Want to thank your editor? Recommend them in writers��� groups. It���s the editorial equivalent of posting a reader review online. And consider sending a signed copy of your book. If your editor doesn���t have space to keep it, they can donate it to a Little Free Library���more readers for your brilliantly edited creation.

This article does not constitute legal or financial advice; for specific issues and questions, you should seek advice from a qualified attorney or financial professional.

Lisa Poisso

Lisa PoissoResident Writing Coach

Lisa Poisso’s innovative Plot Accelerator and Story Incubator coaching fast-tracks authors through story theory and development in weeks while facilitating an author-paced ���developmental edit in a bottle.��� She has decades of professional experience as an award-winning magazine editor and journalist, content writer, and corporate communications manager. She’s also a developmental and line editor, aided by an industrious team of retired greyhounds. For an extra shot of help, subscribe to her monthly Baker���s Dozen newsletter and pick up her free Manuscript Prep guide.

��

Website | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

The post Best Practices for Working with an Independent Editor appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

February 26, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: Leading

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental illness, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc.

A Fear of Leading

A Fear of LeadingNotes:

Leading is not easy. It means being responsible and accountable, making decisions that will have a wider impact, and facing scrutinization for certain actions taken. This fear can cause characters to avoid stepping forward when asked (or needed), resent having this role thrust upon them, and even affect those already in a leadership role.

What It Looks Like

Resistance to being in charge

Avoiding making a final decision

Not wanting to be responsible in bigger ways

Not wanting to speak out or speak one’s mind

Letting others decide

Being risk-adverse

Pointing out one’s flaws and lack of suitability to others

Self-sabotage (to prove to others they aren’t leadership material)

Avoiding conflict and arguments

Bringing on a partner to co-lead

Obsessing about one’s missteps and mistakes

Indecisiveness and hesitation

Asking someone else to pass on bad news

Avoiding being the one to make hard decisions (and instead passing the buck or putting it to a vote)

Pulling back or hiding out in stressful times

Trying to avoid public speaking (preferring email and other “silent” ways of communicating, or having someone else make the speeches)

Being prone to over-analyzing rather than decisiveness

Wanting to keep things smaller and less complicated due to doubts of being able to handle something bigger

Wanting to stick to what’s known rather than innovate and experiment

Setting smaller goals because they are easier to achieve

Feeling not up to a challenge

Resisting or minimizing growth (of a movement, a business, a community) to keep things manageable

Pushing people away

Finding reasons to stay in the comfort zone rather than ask, What’s next?

Seeing the drawbacks, not the potential

Feeling one’s knowledge is inadequate and that can’t be changed

Viewing failures or lackluster progress as proof of one’s inability to lead

Focusing on what could go wrong, not what could go right

Worrying about the repercussions

Pretending things are okay when they are not

The character becoming prickly in situations where they don’t know the answer

Common Internal Struggles

Wanting to hide from responsibility, but feeling cowardly to want that

Wanting to make things better, but only seeing one’s own shortcomings

Believing leading would be a disaster (if the character hasn’t taken on the role yet)

Wanting to do right by others but fearing one’s efforts will only disappoint

Feeling unworthy of the belief others have in their abilities

Feeling like an impostor

A desire to go back to simpler times

Taking criticism to heart

The misbelief that they are only capable of so much, rather than see personal shortcomings as temporary and subject to change

Over-focusing on mistakes and failures rather than successes

Believing successes are due to luck more than skill

Having good ideas but not wanting to be blamed if something goes wrong

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

Holding back great ideas out of the fear of being singled out and asked to lead

Suffering with a less-than-ideal status quo

Being unhappy in a follower role

Being stuck with bad leaders and situations that don’t improve

Feeling like they are living beneath their potential

Having to put up with poor leadership because they are unwilling to step forward

Leading, but with a fear-based mindset that catastrophizes rather than see limitless potential

Being pessimistic about the future

Feeling cowardly for not having the courage to step forward

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

Being asked to take something over

A survival situation where the character is the best suited to lead

Being the oldest in an emergency, so siblings look to the character to lead

Being promoted at work

Being asked to be in charge of a project, committee, event, etc.

When others come to the character in dire need of help

Needing leadership experience to round out college applications

A death in the family that makes the character a successor

Knowing by not stepping up, a greater harm will come

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

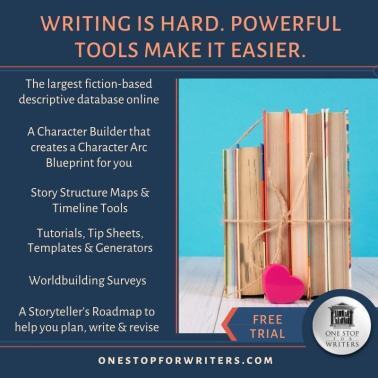

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: Leading appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

February 24, 2022

Spinning a Yarn out of History: How to Craft a Plot from your Historical Obsession

By E. C. Ambrose

Some of the most compelling fiction arises out of the writer’s engagement with a narrow aspect of history. It might be an event with an exciting impact on the people involved or the future of nations. Many authors come to historical fiction because of a personal connection to a distant time and place, and their writing explores the experiences of people who lived in that milieu. My obsession is early technology, and my latest novel was sparked by a footnote.

So how do you transform a passion for history into a compelling narrative?

Begin by framing your concept: the specific niche in history you’d like to write into, and why it excites you. Are you most excited about the setting, the event, the people, or perhaps the transformation around one of those elements? Freewriting about your enthusiasm can hone your focus. Capture this excitement in a brief statement to guide the choices you make as you brainstorm narrative ideas. If you’re developing a counterfactual or supernatural story, be sure to integrate that direction.

I organize my ideas using a spreadsheet for a timeline, characters, specific locations, scene ideas, etc.�� You may prefer a notebook with dividers, or some other format.�� The earlier you can settle on a system, the easier it will be to exploit your notes, both historical and fictional.

Now that you know where (and when) to begin, consider how to build a story about that concept. Here are a few questions to guide you.

1. Where is the most striking conflict in this concept?What is at stake? A battle might be life or death for the soldiers on the field. It might be existential for the future of the region or intensely personal for the groom who tends the warhorses.

Each of these levels can make an engaging narrative, and will suggest the character(s) involved as well as the breadth of the story. A larger, more complicated conflict signals the need for a larger structure to fully reveal it. If you’d like to craft a short story instead, look for a more intimate view into the conflict and explore that impact. Incorporating several layers of conflict adds richness, and shows why this character is invested in this particular conflict. That helps the reader to develop a rooting interest in what happens to them.

2. Who has the most to gain or lose in your concept?This suggests possible characters. To tell the complete story of the battle, you may need characters who have a top-down view like generals or nobility, as well as participants on the battlefield. These affected characters may not all have a narrative perspective in the work, but the protagonist’s encounters with them will reveal new insights. What additional layers of internal or personal conflict will these characters contribute because of who they are, the roles they play, or their own background? Characters with opposing views illuminate the history in a more three-dimensional way. Creating a cast list of the people most impacted, and how they relate to each other can help you imagine scenes and personal moments to build your plot.

Whose stories dominate the current narrative around the history and whose stories haven’t been told? Are you the right author to reveal lesser-known narratives? If you can respectfully present a new perspective, especially on a familiar or perennial historical moment, that can help to set your work apart.

3. What aspects of the milieu are most critical for readers to understand the concept and story?How can you reveal those aspects in the most engaging way?�� Lectures, backstory and summary are the bane of historical narratives.�� Instead, look for ways to embed historical details and context into scenes, through what characters experience, do, or understand. Deliver information through action or discovery, using sensory details to show the setting.�� As your reader experiences scenes alongside your characters, they will absorb the historical backdrop those characters inhabit without needing lengthy passages of exposition. My spreadsheet includes a column for brainstorming how to deliver the historical context my reader will need.

In particular, avoid explanatory dialog in which characters simply tell one another the information you want the reader to have. Instead, consider conflicts and opposing characters. Can they withhold, discover or argue about the information instead of simply delivering it?

4. What expectations will readers already have about this concept?Reader expectations can enhance or distract from your story. For instance, readers of a Titanic novel are aware the ship will sink, and that creates added tension. Which of the characters will survive and how? If your work contradicts reader expectations, either because it’s a counterfactual or fantastical narrative, or because those expectations are flawed, you’ll need to carefully frame the contradictions to draw the reader closer rather than losing their trust because the author appears to have their facts wrong.

As these questions spark ideas for scenes, add those to your notes. Look for ways to increase the conflicts and raise the stakes through arranging those scenes for maximum impact. I use notecards, dealing out possible story and character arcs until I arrive at the most compelling version, or know what I need to brainstorm next.�� Spinning your historical grist into these narrative elements should deliver plenty of material to weave your concept into a story.

Like E.C. Ambrose, graduates of the Odyssey Writing Workshop often go on to expertly tackle big ideas in their fiction. Lectures by E.C. Ambrose and other top writers will be included in this year’s Your Personal Odyssey, a breakthrough program for writers of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. Your Personal Odyssey is a one-on-one online writing workshop combining the intensive, advanced Odyssey lectures with expert feedback and deep mentoring in an experience designed to maximize your learning and improvement. The 2022 application deadline is April 1. Scholarships are available.

E. C. Ambrose writes knowledge-inspired adventure fiction, including DRAKEMASTER (Guardbridge, April 2022) about a clockwork doomsday device based on Su Song’s astronomical clock of 1090 CE, the Dark Apostle series about medieval surgery, and the Bone Guard archaeological thrillers. She is a graduate of, and sometime instructor for, the Odyssey Speculative Fiction Workshop, and lives in the blustery Granite State where she thinks of plot twists from the bench of her floor loom. Find her on Facebook or visit her website to learn about all of her work.

The post Spinning a Yarn out of History: How to Craft a Plot from your Historical Obsession appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

February 22, 2022

When to Kill a Character

Well, Valentine’s Day is in the rearview, so it’s time to move on to a less lovey-dovey topic: killing people. Fictional people, of course!

Let’s face it, some of our characters have to die. Sure, we may have spent hours (days, weeks, decades?) shaping them, planning their backstory, filling their hearts with hopes and dreams. But in the end, it just isn’t their time to shine.

So…

That deer crosses the icy road at the wrong time.

The cable hoisting a plate glass window to the third story breaks.

Or the psycho with the ax chooses your character like he’s Pikachu.

Tragic, right?

But here’s the thing: when it comes to killing, there’s a time and place.

We don’t kill because the scene needs some spice.

We don’t kill because we’ve spotted a plot hole, and killing a character seals it off.

We don’t kill when it’s the easy way out. (Bring on the suffering!)

We don’t randomly kill someone to show readers how bad our baddie is.

And most of all, we don’t kill 1) when the death serves no purpose or 2) if readers aren’t invested in the character. So, make sure the death pushes the story forward in some way and readers have a soft spot for the target (Rue from Hunger Games, for example) before you snuff them out. Emotional currency is king.

I know, I know, you’ve got a sad now, like I smashed your ice cream cone on the ground. So here’s when you can kill:

TO REMOVE YOUR PROTAGONIST���S SUPPORT SYSTEM

Sometimes our characters must hit rock bottom or lose everything before they can find inner strength. Taking away their safety net can trigger devolution or evolution and support their arc���s trajectory.

TO SUPPORT THE STORY���S THEME

Sometimes, there is a cost to holding to a belief or following a certain path, and death may be necessary to fully underscore the weight of the story���s theme. Sometimes, there is no justice. Evil triumphs instead of good. Safety is an illusion. Love means sacrifice, or finding one���s purpose in life may mean surrendering to it. Think about your theme and if this death will support the underlying meaning of the story.

TO SHOW THE COST OF FAILURE

Stakes can be primal, and it needs to be clear to everyone, including readers, when failure means death. If you go this route, invest time into the sacrificial character. Give them goals, needs, and people they would do anything for. Most of all, make readers care about them so their death has impact.

BECAUSE THEY HAD IT COMING

Some people deserve to die. They take risks, fail to heed advice, or are just plain toxic and awful. To show the cause and effect of their actions or provide a satisfying death scene for readers, take the character out in a way that makes sense, is ironic, or rings of poetic justice.

See? Lots of good options for killing. Challenge yourself to make it count so it serves the story in some way.

If you’d like to grab this “When to Kill a Character” checklist to save and print, just go here.

How do you decide when to kill a character? Who was it, and why did you do it?The post When to Kill a Character appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

February 19, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: Failure

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental illness, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc.

Fear of Failure

Fear of FailureWhat It Looks Like

Being content with the status quo

Taking a follower role; letting others lead

The character not doing their best

Apathy or laziness

Shutting down a co-worker’s new idea before it can be adopted

Finding faults in potential love interests

Ending a romantic relationship when it starts to get serious

Turning down new projects or opportunities

Doing something reckless or ill-advised the night before an important test or interview���e.g., staying up all night drinking, then falling asleep and missing the appointment

Procrastinating on a school or work assignment

Not finishing projects

Blaming others when a failure occurs

Projecting an image that encourages low expectations from others

Preoccupation with minor tasks (instead of focusing on the important ones necessary to succeed)

An inability to analyze past failures and learn from them

Being perceived as inflexible or lazy

Making excuses for underachieving

Manipulating others to avoid having to take on certain duties

Perfectionism; obsessing so much over making things perfect that the work never gets done and the end product is sabotaged

Common Internal Struggles

The character doubting their abilities or intelligence

The character being certain of their own failure when they’re entirely capable of winning

Worrying that failure will make others think less of the character

Worrying about disappointing others

Envisioning a desired future but doubting that it will ever come to be

Past failures replaying in the character’s head on a loop

Struggling with shame

Wanting to take on certain projects or opportunities but being too scared to try

Creating internal arguments against an appealing but risky opportunity

Flaws That May Emerge

Apathetic, Cautious, Cowardly, Cynical, Defensive, Devious, Evasive, Flaky, Forgetful, Frivolous, Humorless, Hypocritical, Indecisive, Inflexible, Inhibited, Insecure, Irrational, Irresponsible, Manipulative, Mischievous, Nervous, Perfectionist, Rebellious, Reckless, Self-Destructive, Self-Indulgent, Stubborn, Temperamental, Uncooperative, Withdrawn

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

Missing out on opportunities that the character would be good at or enjoy

Being looked down on by others (for a lack of ambition or ability)

Arguing with parents and family members who call the character out for not trying hard enough

The character being limited in what they’re able to achieve in life

Being unfulfilled

Being unable to succeed professionally

Being unable to maintain a meaningful and healthy romantic relationship

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

Being assigned a high-profile work project

The character’s work partner falling ill, leaving the character to handle things on their own

Being asked to join a committee or volunteer group

Being asked out by someone the character likes

A romantic relationship escalating to a new level (the other person saying I love you or suggesting they move in together)

A negative influence speaking doubt and failure to the character, echoing their own thoughts

Being introduced to a scenario similar to the one that caused the character’s fear of failure

Experiencing a failure���real or perceived���that reinforces the character’s fear (their marriage falling apart, their child dropping out of school, etc.)

Being pitted against someone who is superior and is sure to win

Being rejected by a potential love interest

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: Failure appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

February 17, 2022

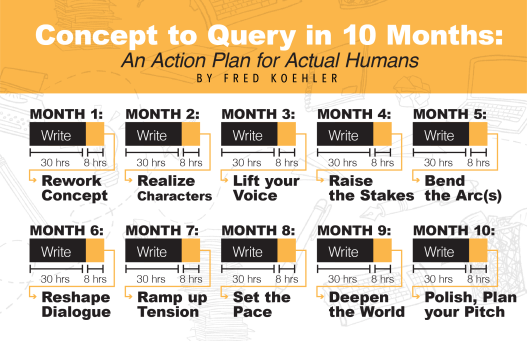

Your Novel: Concept to Query in 10 Months

An Action Plan for Actual Humans

An Action Plan for Actual HumansBy Fred Koehler

Like almost every other writer I know, I���m not a full time novelist. Publishing is, at the best of times, really slow. In the meantime, kids need braces. Cars break down. The rent doesn’t pay itself.

And yet, through each of the last three years, I managed to get a new novel approved by my agent and out on submission while working full time.

Here’s how.

It starts with every writer’s favorite acronym. B.I.C. Butt In Chair. You MUST make the time to write.

Some superhuman writers can do this in a sprint. Fifteen hour days. Doritos for dinner. Bi-weekly personal grooming. To those of you successfully writing and selling novels using a quick draft methodology, I tip my hat. The rest of us mere mortals, however, might need an alternative approach.

For me, B.I.C. means getting up and out the door two hours early each day. It also means coffee at the only fast food joint in town with an open lobby at 5 a.m. (For a while this included breakfast until I put on ten pounds from all the hash browns.)

However you get in the time, I find that eight hours of writing per week is enough to finish drafting a novel in ten months. But that���s just the drafting. I also like to polish as I go. This method is likely to resonate well with ���Plotters��� who love outlines and keep detailed notes. As for ���Pantsers��� (so named because they write by the seat of their pants), these exercises can be infused in a more free-flowing way.

Each week, work towards eight hours of just plain writing. Then, add two to four hours of polish based on an element of craft that changes month by month. Once you polish a scene to perfectly embody a specific element of craft, use that section of writing as a litmus test for the rest of your draft.

Month 1: Rework the ConceptYou want your “Big Idea��� to be fresh, easy to explain, and make a promise to the reader of an unexpected and satisfying journey. If it���s similar to existing stories, difficult to understand, or lacks enough conflict to be intriguing, now is the time to go through ideation exercises before you write yourself into a corner. Here���s a link to a favorite of mine called Mythic Mashup.

Month 2: Realize your Characters“We fall in love with character first.” This advice was given to me by a well-known editor as she kindly rejected a novel. Sadly, I���d filled my incredibly fun world with cardboard characters. Don’t do that. Instead, give your characters flaws so deep you sometimes can’t tell apart the heroes and villains. Make it worse with impossible choices where every conceivable decision has terrible consequences. This up-front understanding of your characters will give them nuance that makes them unforgettable.

Month 3: Lift your VoiceHumor, wit, imagination, confidence, authority ��� these are all elements of Voice. You want yours to feel fresh, confident, and distinct. You want readers to know they���re in the hands of a master storyteller and excited for the ride ahead. Is this a tall order? Yes. But I find it easier to dial in Voice when I���m only a few chapters deep instead of trying to infuse it once the book is drafted.

Month 4: Raise the StakesYour stakes should be well-established by this point in your story. If your character does not reach their goal, what does it cost them? Increase that cost tenfold and, in your opening chapters, show us why it matters so much. The more that���s at risk (physically and emotionally) for a character we love, the more we have to see them through.

Month 5: Bend the Arc(s)The characters at the beginning of your story must undergo trials to gain the emotional and physical strength they need to overcome the major conflict. You bend the arc by giving your characters greater odds to overcome. Essentially, keep asking “What would make it harder for them?” Practice this in even your opening scenes to foreshadow the overwhelming challenges you���ll need to build for the climax.

Month 6: Reshape DialogueDo your characters feel like individuals with distinct personalities? Do words and actions reflect how they would actually speak / think? Work to make conversations feel so natural we can envision the characters in our heads. As you rework the first half of your novel, find a section of pitch-perfect dialogue you can channel for the rest of your draft.

Month 7: Ramp up the TensionTension is the ability to create conflict on the page that tugs at your reader���s imagination and gives them concern for the outcome. This can happen in big ways through the main plot but also through tiny details in each scene. Teach yourself to add an extra element of tension to each scene, and you’ll start to automatically build it into your remaining chapters.

Month 8: Set the PaceAs you revisit key scenes, revise the intentional swiftness or slowness with which you move us through those moments. If it’s high-octane action, explore the senses during a breath between bullets. If nothing happens on the drive across Texas, cut the chapter to a single sentence.

Month 9: Make the World Deeper and WiderWhether it���s the 1920���s fashion industry or an alien cyborg planet, pay close attention to details and descriptions that pull us into your world. Are your scenes thoughtfully and artistically imagined? Are there enough curious details in the landscape and character interactions to reveal what makes it special?

Month 10: Polish & Plan your PitchYou’re going to keep polishing in month ten. Revisit each element of craft and look for scenes that still have room for improvement. But this is also a great time to review the ‘shelf’ on which your book will sit. Which publishers fill that shelf? Who edited those books and which agent did the deal? Did you research those gatekeepers and personalize each query? A thoughtful pitch plan, even if it ends in rejection, demonstrates your professionalism and helps grow your network.

I recognize that I’ve opened the door to scrutiny here. Some writers might define an element of craft differently. Some will feel I’ve got my timelines or order of importance mixed up. But like I said, this is a starting point, not a finished roadmap. Rework the formula based on your own writing habits. The goal of this method is to infuse your story with critical elements of craft that lead to publishing success.

And if the manuscript doesn���t feel like it���s ready, take an extra month. Let it simmer a while longer. Ask your beta readers to go heavy on a specific chapter or scene. Whatever you do, keep your butt in the chair. The world needs your stories now more than ever.

Ready Chapter 1 has openings in a first-of-its-kind academy designed to take writers from concept to query over 10 months with editors, agents, and bestselling authors who share workshops and unique writing tools. Here���s a discount code: WHW22

Fred Koehler is an artist and storyteller whose real-life misadventures include hurricanes, sunken ships, and shark encounters. His writing and artwork have earned numerous starred reviews and awards, including a Boston Globe-Horn Book Honor Award. Fred lives in Florida with his wife, kids, and a rescue dog named Cheerio Mutt-Face McChubbybutt. He’s passionate about elevating new voices in writing and founded Ready Chapter 1 Academy to help students of all levels write, polish and pitch their novel in less than a year.

The post Your Novel: Concept to Query in 10 Months appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

February 15, 2022

The Measure of a Character

By Christina Delay

One of my favorite characters of all time is Star Trek���s lovable android, Data. If you aren���t familiar with The Next Generation, and Data in particular, the most important thing you need to understand is Data is an android with a life mission of becoming more human. He���s the Pinocchio of space, but with better decision-making skills.

While rewatching the series for the tenth time���because of course we need to indoctrinate our oldest patootie into this world���we came across the episode titled ���The Measure of a Man.��� If you haven���t seen this episode, or if it���s been a while, please take a few minutes to watch this clip.

The crux of the episode is this���what (or who) qualifies as sentient life? And it made me wonder about my own characters. At what point do they become ���sentient���?

There are tons of character interview questions for authors to get to know their characters. My deep, dark secret? Character interviews have never ever worked for me. At least, they���ve never helped make my characters seem sentient.

But what if we applied Star Fleet���s criteria for sentient life to our characters and judged them under the same microscope that Data was judged in ���The Measure of a Man?��� Will doing so help us understand the core of our characters better? And if so, do our characters measure up?

Intelligence

The first criteria that sentient life must meet is intelligence. Does the being possess the ���ability to learn, to understand, and to cope with new situations?���

I mean, yes, we can force our characters to learn, to understand, and to cope with new situations. We are their creators, after all. But at what point do our characters become organically intelligent? In other words, when do our characters begin to tell us, their creator, if a certain decision or action is within character for them?

In the past, it has taken me a long time to get to this point with my characters. I have to live with them and immerse myself in their world for a while. Korrina, the main character in my Siren���s Call series, took years to develop because I, the creator, had a different idea of who she should be than who she truly was. (And she is nothing if not stubborn.) My idea of who she should be blocked her true self from coming out.

Once I let Korrina be her snarky, acts-now-apologizes-later self, she became organically intelligent. She was able to learn and to understand new, big concepts (such as the existence of mythological beings and that she���s a Siren with a magic object attached to her soul), as well as cope with new situations in ways that were realistic, believable, and unique to her character. It is her intelligence that adds shape to her character, as well as her ability to learn from her mistakes that makes her seem sentient.

Self-awarenessMy critique partner, Julie Glover, is an absolute whiz when it comes to crafting characters who appear self-aware. One of her main characters in SHARING HUNTER, Chloe, is so self-aware that she occasionally jumps into conversations Julie and I have with each other.

Dr. Maddox, in the Star Trek episode we���re referencing, claims that self-awareness is achieved when ���You are conscious of your existence and your actions. You are aware of yourself and your own ego.���

Are our characters capable of becoming self-aware?

I argue, yes, they are.

When our characters do something surprising or different than we had planned, our characters become self-aware.

When our characters speak in a way that is totally foreign to how we, the author, processes the world, they are self-aware.

When Julie Glover���s main character, Chloe, suggests that she and her best friend Rachel share a boyfriend the last semester of high school, she doesn���t just suggest it. She knows Rachel won���t go for this idea unless she sets the situation up perfectly, orchestrates the slow leak of idea building upon idea, and uses phrases like ���that smokin��� hot piece of boy-bacon won���t last long in the high school meat market.���

However, she also realizes that if she comes on too strong, Rachel will balk and the idea will be over before it has a chance, ���for Twain���s sake.���

The way Chloe masterminds her sharing-a-boyfriend scheme is just so…Chloe. (And if you haven���t read SHARING HUNTER yet, you really must.)

ConsciousnessThis one is, I believe, the hardest criteria for our characters to meet. Do our fictional characters experience true consciousness?

Consciousness is defined as ���the quality or state of being aware especially of something within oneself.���

In Data���s example, that is the question that was left unanswered. It was up to the court to decide if Data met the requirement of consciousness in even the smallest measure. Is Data a machine, programmed to answer an infinite number of questions, or does he have consciousness���is he capable of original thought?

So I will follow Star Trek���s example. What do you think?

Are our characters derived from our own subconscious, meaning that the questions they pose and the answers they find are actually from deep inside our own brains? Or do these characters speak for themselves, with thoughts and ideas that belong to them?

It���s an interesting concept to ponder. What is sentient consciousness? What is life?

And do your characters have it?

Our best characters don���t simply occupy the page but come to life���for us and for our readers. They possess intelligence, feel self-aware, and seem to be, or perhaps are, conscious.

Consider these traits as you write characters your readers will connect with, and use these traits to help your readers feel that your characters are almost as real as their own selves.

Live long and prosper.

Christina Delay

Christina DelayResident Writing Coach

Christina is the hostess of Cruising Writers and an award-winning psychological suspense author. She also writes award-winning supernatural suspense under the name Kris Faryn. You can find Kris at:

Bookbub �� Facebook �� Amazon �� Instagram.

The post The Measure of a Character appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

February 12, 2022

Introducing…The Fear Thesaurus!

Fear is an undeniable part of the human experience, for both real and fictional people. At its most basic, it warns our characters of potential danger and encourages them to take actions and make specific choices that will keep them safe. While unpleasant, it’s an important warning system meant to protect them from harm. But the system breaks down when a fear grows to the point of becoming overwhelming and crippling.

Debilitating fears play an important role in story and character arc, so we’ve decided to delve into this topic for our next thesaurus at Writers Helping Writers. Not just any fears, though���the virulent ones that stymie characters and derail them from their goals and dreams. To help you write your character’s greatest fear realistically, we’ll be exploring the following aspects for each entry:

What It Looks Like. Fears look different for each character based on a number of personal factors, so we’ll be providing a variety of manifestations for you to consider. Know your character’s personality, their sensitivities, and their personal boundaries���things they’re not willing to do because it will be triggering. Being intimately familiar with your character will give you a good idea of how their fear will manifest in various areas of life.

Common Internal Struggles. Fear will cause the character to doubt, obsess, and worry���many times, to an unhealthy degree. If they recognize that their preoccupation borders on the irrational or that it’s making certain desirable things impossible, that knowledge will war with their need for safety, generating internal conflict. The way they deal with it (or don’t deal with it) will have consequences that will impact their forward progress, so this is an important aspect of fear to think about.

Flaws That May Emerge. As your character tries to avoid what they fear, they may undergo a personality shift. A fear of commitment may cause the character to become superficial in their relationships and conversations. The character who is afraid of rejection may become abrasive, uncooperative, or dishonest���flaws that will keep people from getting close enough for a possible rejection to sting. Someone who is scared of losing control can become incredibly controlling and fussy. These traits are effective at protecting the character, but they will cause a myriad of other problems that then will have to be addressed.

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life. If your character has a debilitating fear, you’ll need to show it clearly to readers through the context of their current story���no expository paragraphs or info dumps. An effective way to do this is by showing how the fear impacts the various areas of the character’s life. In this field, we’ll offer ideas on the minor inconveniences and major disruptions a fear can create.

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear. This is another way you can clearly show your character’s fear���by introducing situations that will trigger them. But they’re also helpful for providing opportunities for growth. As your character moves through their story toward their goal, their fear will block them. For them to achieve their objective, at some point, they’ll have to confront their fear and put it in its rightful place. Knowing which scenarios will trigger their fears will allow you to build those important growth opportunities into the story.

Fear is such a vital part of your character’s arc and their story. Our hope for this thesaurus is that it will provide insight and guidance for this important element. The first entry will go live next Saturday, so stay tuned!

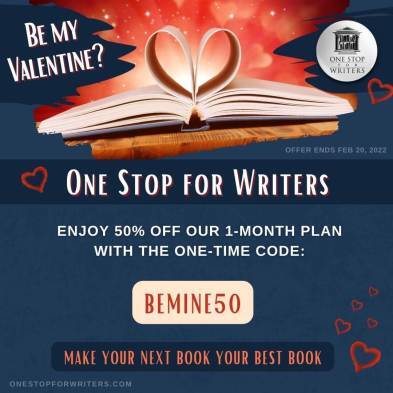

Come Join Our One Stop Family!

Don’t forget that we want to be your Valentine this year, and so we’ve cooked up a one-time 50% discount code for One Stop for Writers. Just sign up for a free account and then use the code:

BEMINE50When you subscribe to the 1-month plan. You’ll get a month for the cost of a latte, and kick butt on your writing goals because everything you need to write powerful stories, including a massive Show-Don’t-Tell Thesaurus database and Storyteller’s Roadmap, is at your fingertips!

Deal ends Feb 20th, 2022.

The post Introducing…The Fear Thesaurus! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

February 10, 2022

Stoking Your Story���s Fire: Three Considerations for Revising Scene by Scene

By David G. Brown

The Two Pillars of StorytellingAfter my first couple years as a fiction editor, I realized that all of my developmental feedback for clients fit into one of two categories. The first is immersion: the quality of a narrative that transports readers to another time and place. The second is emotional draw: that which maintains readers��� interest in a character and thus keeps them turning pages.

Immersion is achieved with scene-based writing, which means a focus on the protagonist���s moment-to-moment experience of setting and conflict. A reader���s sense of immediacy grows out of sensory details, movement, action, and dialogue.

Emotional draw is more complicated. Readers are diverse, and each one brings a slightly different reason for turning the page. But the main components are:

The author���s first job, whether they are writing fiction or narrative nonfiction, is to transport readers into their characters��� world. Context is important in any story, but sensory details are paramount since they are key to a reader���s imaginative experience of the text.

Comb through your scenes with this principle in mind. On every page, ask yourself what your readers might be seeing, hearing, smelling, and feeling. Do they know within a few sentences where a scene is taking place? Can they picture the surroundings? Do they have a physical sense of the characters moving through and occupying space in this locale?

Judge each sentence by the following criteria: does it convey the focal character���s moment-to-moment experience of the scene? Or does it instead provide context?

The more scene you have on each page, the deeper your readers��� potential immersion. As soon as you showcase context, your readers��� imaginative experience diminishes. That���s not to say there isn���t room for snippets of context. It���s a question of balance.

Context includes setting, world-building, backstory, and even interiority���your protagonist���s analysis and reflections. Again, context is important, but it works best when it surfaces in hints rather than explanations.

Treat your readers like detectives���give them clues and let them come to their own conclusions about context.

Chapter Arcs and ConsequenceHere���s another reason scene-based writing is so important: it���s where both plot and character come to life.

When characters make decisions and take risks, readers see them for who they really are. Witty asides and snippets of narrative context can give a story much depth, but the true essence of character is contained in what they are willing to do���or not���to get what they want.

Therein lies the nugget of a chapter arc: a character either takes action toward a goal or reacts to a new obstacle. The result is a consequence���their path forward has changed. In most cases, the scene will have some bearing on the overarching narrative trajectory (more on trajectory in a moment), but the action/reaction and consequence might also develop a subplot.

Take a close look at each scene in your manuscript and ask yourself:

Does the focal character make a choice or take action in pursuit of a goal?Does this choice or action result in a consequence that leads into the next scene?If the answer is no or if you aren���t sure, flag the scene for reconsideration: either bring it into the story���s chain of consequence or send it to the chopping block!

Plot is a Chain of ConsequenceA large part of emotional draw flows out of trajectory: a character struggling toward a goal. As the protagonist makes decisions and takes risks in pursuit of their goal, they court failure of some kind. If nothing is at stake, it���s extremely difficult to hold readers��� interest, and without a specific goal, the story becomes aimless.

In terms of structure, the beginning of a narrative is the point when a character���s underlying motivation crystallizes into this clear, relatable, and specific goal���the first link in the story���s chain of consequence. Keep in mind, many novels open sometime after this point. For example, in Moby Dick, Ahab���s inciting incident is implied.

In genre fiction, the narrative goal is often in sharp focus: it���s a quest to save the world or a mission to stop a killer. While emotional draw in literary fiction is usually connected to deeper thematic elements, the narrative goal is still a major component, even if the quest is subtler.

A protagonist���s goal is sometimes referred to as a narrative bridge���a question asked in the beginning of the novel that is answered by the end. The protagonist���s goal is the question, and whether or not they achieve it is the answer. This answer also forms the final link in the story���s chain of consequence.

The rest of the narrative chain lies between the inciting incident and the climax. That means each scene causes the next. In other words, if you map out your story scene by scene, there should be a causal transition between each segment: this happens, therefore this happens, but then this happens, therefore��� The alternative lacks momentum; it���s anecdotal: this happens, and then this happens, and then this happens.

Here���s a simple example: Rumpelstiltskin.

The miller���s daughter is the protagonist. Her inciting incident comes when her father brags to the king that she can spin gold from straw. She is therefore locked in a room where she is expected to perform her magical feat.

Father and daughter are in deep trouble, but then Rumpelstiltskin appears and offers to do the deed in exchange for her necklace. She agrees and therefore presents the king with his gold the next morning. But then the king wants even more gold; therefore the miller���s daughter needs Rumpelstiltskin���s services again and must make greater and greater sacrifices to pay for them.

The chain of consequence wraps up at the climax: eventually, when Rumpelstiltskin comes to collect on his final demand (her first-born child), the miller���s daughter tries to renegotiate. He gives her an unlikely escape clause: she must guess his name. She therefore follows him into the forest, finds his home, and overhears him singing his secret.

A novel is much more complex, especially given subplots like interpersonal arcs and side quests. For this reason, it���s a good idea to create separate causal maps for your story���s main trajectory as well as the secondary storylines. However, when you look at the big picture, each scene should fit into one of these chains of consequence.

Bringing It All TogetherThough this article first touches on the importance of your readers��� story-world immersion, you are better off to focus your initial self-editing efforts on your manuscript���s chain of consequence. You might find that entire scenes aren���t pulling their (causal) weight, which means they either need to be cut or substantially changed to align with the protagonist���s trajectory. For this reason, it���s best to nail down the structure before you start fleshing out and polishing scenes.

To conclude, here are a few more tips for your next self-editing adventure:

Take time away from your project. Work on something else for a month or two!On your next read through, pretend your worst enemy is following along over your shoulder. What would they say? What would they roll their eyes at?Between each draft, consider your story from wildly different angles���what if the protagonist and antagonist traded places? What if you switched genres? How would the conflicts play out in a different time and place?Don���t be afraid to tear down walls and install a new front door. In fact, sometimes we need to burn down the house altogether to find the best way forward.

David G. Brown is the founder of Darling Axe Editing and Darling Indie Marketing . He is an award-winning short fiction writer, and his debut novel is represented by the Donaghy Literary Group. He has published poetry, fiction, and nonfiction in magazines and literary journals, and he has an MFA in creative writing from UBC. David lives in Victoria, Canada, in the traditional territory of the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations.

The post Stoking Your Story���s Fire: Three Considerations for Revising Scene by Scene appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

February 8, 2022

Zig Zag Plot Arc

By Marissa Graff

As writers, the classic arc-plot diagram is burned into our brains. The one conveying that our characters should move through our books in one steady climb, both externally and internally. But what if the visual of a smooth line is sabotaging the way we convey our character���s journey? What if it���s not presenting the reader with an accurate picture of how diverse and rigorous a character���s journey really needs to be to deliver them to a satisfying and believable ending?

If we think of how a story filled with obstacles and victories plays out, a better visual representation of story looks more like a zigzag. Think of the old adage one step forward, two steps back.

Speaking of stepping back, let���s talk about why an arc-plot model fails to serve us as writers. Internally, if the protagonist only moves forward in their development and experiences constant wins, there���s a sense that the misbelief they had when we first met them wasn���t such a big deal after all. If it���s that easy to change, the story seems less crucial.

Externally, there���s little to no tension in a story where the protagonist keeps winning in a bid against an antagonist. Allowing the character to struggle and be tested not only draws the reader in, it���s simply more interesting for the character���s journey. It keeps us guessing and creates balance. Readers want to see the character face overwhelmingly difficult odds. They want every win to feel earned, and they want to be able to compare it to a previous instance where the character wasn���t quite ready.

So how can you achieve a zigzag character arc that gives the reader a far more believable experience?

Feel the RhythmWhen you step back and look at your draft, outline, or scene tracker, feel out the rhythm of your protagonist’s victories and setbacks. If they���ve just had a scene where they overcame something that would have been impossible to defeat when we first met them, consider presenting them with a challenge that shows their lack of readiness for even bigger change. Then, we will not only understand that there���s more story needed for their ultimate change, but we will also maintain the tension needed to bring us to the finish line. If the character only demonstrates the ability to overcome obstacles, the book begins to feel too easy. We won���t see the character struggle in a way that equips them with what they didn���t have in the opening.

Similarly, if you only deal your protagonist blows, they won���t seem gradually prepared for their ultimate victory come climax time. We won���t see how they���ve been readied little by little, gaining confidence and skills along the way. Utilizing a balance of wins and losses makes the story more interesting and the ending more earned.

Craft Wins with PrecisionIsolate your protagonist���s victories as their own thread. You���ll want to consider manipulating their wins with somewhat deliberate precision. It���s helpful to think of where you imagine your character to be in the end and work backward. Dismantle that picture into sizable, actionable pieces that create the finished whole.

At first, consider allowing your character to take small steps toward change, ones that bring about proportionately small victories. That will create a sense that change is hard and growth takes time. It stands to reason that the character would take little steps at first because the risk isn���t as high. But as their confidence increases and experience shapes them, their steps toward change can become bigger and the wins can yield greater reward. This gradual thread of victories will also create the feel of a believable story.

Craft Defeats with PrecisionIsolate your protagonist���s losses as their own thread. You���ll want to think about manipulating the obstacles so that they start small, but gradually grow more daunting. Consider making the setbacks the character faces increasingly painful for them. It���s helpful to create a list of the things your character cares about. Then, order the list from things that are least important to most important in terms of personal value. That way, If something of lesser value is on the line and the character is hit with something small at first, it doesn���t deal them a complete defeat. They still have room to want to grow and change. But as your story plays out, you���ll want to move up the list of things your character cares about, closing in on the things your character values most so that they���re efforts must line up accordingly. The smaller the blow, the smaller the effort needed to respond to the obstacle. Or, the easier it is to ignore. But the greater the blow and the more that���s on the line, the more motivation the character will need to summon in order to change. That increase in motivation and their willingness to change will take time. So ordering the setbacks from small to large will yield a realistic series of reactions.

Crafting a zigzag path earns both your plot and your character���s inner journey far more believably than the image a smooth arc suggests. By testing your protagonist���s willingness to change, the reader can then gauge their readiness for the climax. If they���re ready for change all along, the plot feels unnecessary. But if it���s going to take time and a series of wins and failures to crush the protagonist���s misbelief, then every bit of the plot feels needed. And perhaps more importantly, the ultimate victory in the climax feels that much sweeter.

For more information on using conflict to create a compelling two-steps-forward-one-step-back character journey, check out The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles. Marissa Graff

Marissa GraffResident Writing Coach

Marissa��has been a freelance editor and reader for literary agent Sarah Davies at��Greenhouse Literary Agency��for over five years. In conjunction with��Angelella Editorial, she offers developmental editing, author coaching, and more. Marissa feels if she���s done her job well, a client should probably never need her help again because she���s given them a crash-course MFA via deep editorial support and/or coaching.

Website��|��Twitter��|��Instagram��|��Facebook

The post Zig Zag Plot Arc appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1014 followers