Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 50

August 6, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: A Loved One Dying

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental health condition, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc. Please note that this isn’t a self-diagnosis tool. Fears are common in the real world, and while we may at times share similar tendencies as characters, the entry below is for fiction writing purposes only.

Fear of a Loved One Dying

Fear of a Loved One DyingNotes

At some point, everyone loses a loved one. It’s an inevitable part of life. We all worry about it to a certain extent, but for some characters, the fear of someone close to them dying can take over their life. Sometimes it’s rooted in the character not wanting to see their loved one suffer, but it can also be centered on uncertainty about death itself, the character’s ability to cope on their own, or how their life will change with their beloved no longer in it.

What It Looks Like

Being overprotective of a loved one’s health

Refusing to talk about the possibility of a loved one’s death (even if it’s likely to happen)

Being morbidly obsessed with death or funereal trappings, such as Victorian death masks and portraits

Limiting a child’s freedom and independence to keep them safe���not allowing them to drive, stay out late, or visit new places, for instance

Being obsessed with germs and sanitation

Forcing family members to take part in health crazes that promote longevity

Holding onto things as they are instead of allowing people and situations to evolve

Having panic attacks when thinking about the death of a loved one

Refusing to make contingency plans for a loved one’s death (not buying life insurance or making a will, etc.)

Refusing to accept a loved one’s illness or terminal diagnosis

Visiting psychics to gain insight into a loved one’s well-being and future

Investing in extensive security measures to keep family members safe

Common Internal Struggles

Obsessing about a loved one’s death and what it would mean for the character

Wanting to hold on tightly to a child while also knowing they need freedom to grow

Letting anxiety and fear control decision-making

Fearing the passage of time despite recognizing its inevitability

Knowing their fears are irrational but being unable to overcome them

Worrying constantly about worst-case scenarios despite knowing they’re unlikely to occur

Understanding that death is a part of life but being unable to accept it

Wanting to control a loved one (to keep them safe) but fearing it will drive them away

Flaws That May Emerge

Controlling, Fanatical, Fussy, Gullible, Irrational, Melodramatic, Morbid, Needy, Nervous, Obsessive, Paranoid, Possessive, Superstitious, Worrywart

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

The character’s neediness pushing loved ones away

Losing sleep from worry and anxiety

The character neglecting their own self-care because they’re so consumed with the health of others

Being plagued with worry and unable to enjoy life when the loved one is away

Being unable to watch the news or participate in social media because the stories about people losing loved ones are too upsetting

The character’s relationship with their children deteriorating because the kids are tired of being smothered and not trusted

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

A close friend unexpectedly losing a family member

Seeing a TV show or movie in which the character loses a spouse or child

A mass shooting or natural disaster resulting in extensive loss of life

A loved one having a near-death experience

A loved one becoming terminally ill or being diagnosed with a debilitating disease

Discovering that a child has been engaging in risky behaviors (racing their car, skydiving, driving under the influence, etc.)

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

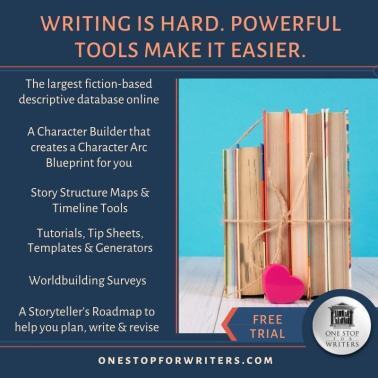

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: A Loved One Dying appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 3, 2022

Coming Soon: The Conflict Thesaurus (Volume 2)

Some things are harder than others: getting up to work out rather than sleeping in. Not eating that entire container of salted caramel gelato. But one of the hardest? Waiting for a sequel.

When it comes to finishing off an amazing novel, your brain goes into fourth of July mode: The characters, the world! You want more, and then sometimes, joy of joys, you discover there will be a sequel. It’s an instant sugar high. And then of course the realization hits that it’s going to be awhile. You’re a writer, so you how much goes into producing a book. It’s tough, because you know you have to wait, even though you want to do nothing more than dive right back into that reality again.

Becca and I won’t pretend our second volume of The Conflict Thesaurus is on the same level as your favorite fiction series, but if you’ve read the first guide, you know it’s packed with game-changing ideas on how to leverage conflict. And if you have been waiting, there’s only a month-ish to go, meaning it’s time to share a bit more about Volume Two.

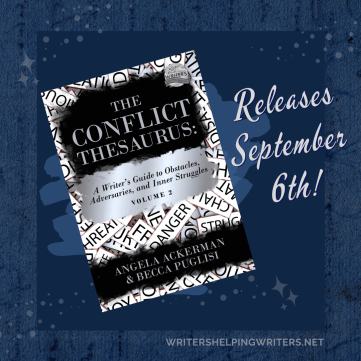

First up…the cover!

First up…the cover!Isn’t she pretty?

Silver is the perfect match for gold, and together these books will add serious storytelling ammo to your writerly toolkit because you’ll have non-stop ideas on conflict, making it easier to choose meaningful problems and struggles that draw readers in and further the story.

Next, the back jacket.THE CONFLICT THESAURUS, VOLUME 2:

A Writer’s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles

A story where the character gets exactly what they want doesn���t make for good reading. But add villainous clashes, lost advantages, power struggles, and menacing threats���well, now we have the makings of a page-turner. Conflict is the golden thread that binds plot to arc, providing the complications, setbacks, and derailments that make the character���s inner and outer journeys dynamic.

FORTIFY YOUR STORY BY ADDING MEANINGFUL CONFLICT AT DIFFERENT LEVELS

Inside Volume 2 of The Conflict Thesaurus, you���ll find:

A myriad of conflict options in the form of power struggles, ego-related stressors, dangers and threats, advantage and control losses, and other miscellaneous challengesInformation on how each scenario should hinder the character on the path to their goal so they’ll learn valuable life lessons and gain insight into what’s holding them back internallyInstruction about using the multiple levels of conflict to add pressure through immediate, scene-level challenges and looming problems that take time to solveGuidance on keeping a story���s central conflict in the spotlight and utilizing subplots effectively so they work with���not against���the main plot lineAn exploration of the climax and how to make this pinnacle event highly satisfying for readersWays to use conflict to deepen your story, facilitate epic adversarial showdowns, give your characters agency, infuse every scene with tension, and moreMeaningful conflict can be so much more than a series of roadblocks. Challenge your characters inside and out with over 100 tension-inducing scenarios in this second volume of The Conflict Thesaurus.

If this is Volume 2, it means there’s a Volume 1! Where do I find this mother lode of conflict?

If this is Volume 2, it means there’s a Volume 1! Where do I find this mother lode of conflict? Right here. Read a sample if you like to see how it will help you level up your story. And a bonus: it’s the Kindle deal of the month at Amazon.com & Amazon.ca., so you can grab it right now for .99 cents. (affiliate link)

Will there be a preorder?Sorry, no. We’ve tried a preorder in the past, but a certain online store made a mess of it (costing us hundreds of sales), so we’d rather not have that happen again. But if you’d like a notification if the book comes up early, add your email here.

Can I get an ARC of The Conflict Thesaurus, Volume 2?Every book launch we give out 50 Arcs, and unfortunately these have already been distributed. (Sorry.) We would love it if you would review the guide when it releases though. It would mean the world to us!

Do you have a Street Team? Can I help?Yes, yes, and YES! If you would like to be part of our Street Team, you can sign up here. We would love to have your help. Plus, being on the inside of a book launch means you can apply what we do to your own book launch strategy. Win-win!

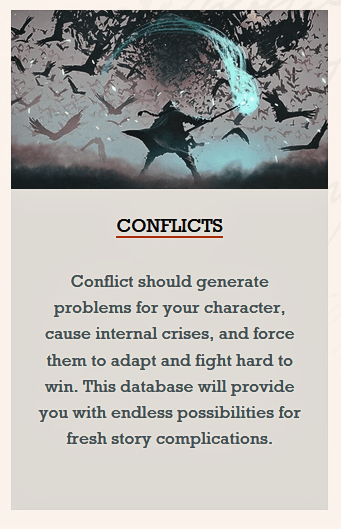

Can I access The Conflict Thesaurus Volume 2 at One Stop for Writers?

Yes! If you’d like to take a look at the full list of scenarios from both books, you can find the Conflict Thesaurus here along with the rest of the topics in our show-don’t-tell database. Start a free trial if you’d like to poke around & view it in full.

(TIP: if you like to use our books for character building, try the Character Builder. It contains all our databases and will help you step by step as you build a character, and connect all the characterization dots for you.)

Did I miss a question? If so, please ask, and I’ll be happy to answer!Thanks so much for always supporting us. September 6th will be here soon, and we can’t wait. We hope this book is everything you need, and more!

The post Coming Soon: The Conflict Thesaurus (Volume 2) appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 2, 2022

An Antagonist vs a Villain: What’s the Difference?

By Neil Chase

What’s the difference between an antagonist and a villain? We often see these terms used interchangeably, but there’s a big difference between them, and you need to know which is the right one for your story.

What Is an Antagonist?In literature and film, an antagonist is a character or force that actively works against the protagonist or main character. Think of them as a roadblock with a clear purpose and well-defined reasons for their choices and actions.

The antagonist may be an institutional force, such as an oppressive government, or an individual, such as a villainous mentor or a romantic rival. Antagonists can also be nature itself, such as in the case of a severe drought or a hungry animal.

In addition to providing conflict and tension, antagonists also help to create a stronger sense of empathy for the protagonist by highlighting their strength and determination in the face of adversity. And while they may cause difficulties for the story’s protagonist, they are not necessarily bad people. Antagonists play an essential role in making a story more memorable.

What Is a Villain?

A villain is an amoral or evil character with little to no regard for the general welfare of others. They are driven by ambition, greed, lust, or a desire for power or revenge.

Whatever their reason, villains typically use underhanded methods to try to achieve their goals. This might include deception, trickery, or violence.

While villainous characters can seem simplistic, they can be complex and even sympathetic if written well. In some stories, the villain might be the only one who understands the true nature of the conflict. This can make for a captivating and thought-provoking story.

Are All Villains the Antagonist of a Story?Villains are a great addition to a story. Thanks to their lack of morals and self-serving attitudes, they immediately add conflict, tension, and suspense. But not all villains are created equal.

In some stories, the villain is the clear-cut antagonist, standing in opposition to the protagonist and working to foil their plans. In others, however, the lines are more blurred. The villain may not be an active force opposing the hero; instead, they may simply have their own goals and motivations in parallel with that of the hero.

Are All Antagonists the Villain of a Story?In any good story, there is typically a protagonist and an antagonist. The protagonist is the main character of the story, while the antagonist is the opposing force. They provide conflict and help to drive the story forward. However, not all antagonists are villainous. In some cases, the antagonist may simply disagree with the protagonist or pose a challenge. They might even share the same goal, but have different methods to reach it.

In conclusion, while antagonists and villains are cut from the same cloth, they aren’t necessarily the same. To clarify, here are some popular examples of each.

A Character Who Is an Antagonist and a VillainHans Gruber in Die Hard is a classic villain, who is also the main antagonist to the hero, John McLane. Hans is an evil character intent on harming others for his own benefit. He is strongly motivated by greed – he wants the money in the Nakatomi Plaza vault, and he’ll stop at nothing to get it.

A Character Who Is an Antagonist But Not a VillainSamuel Gerard in The Fugitive is a textbook antagonist. He works in direct opposition to Richard Kimble’s attempt to escape, and spends the entirety of the story tracking him down, because it’s his job. It’s not personal and he has no ulterior motives. He’s simply really good at what he does, and he’s been tasked with bringing a known fugitive to justice. He’s not a villain. There are not evil intentions to what he does, but he is the primary antagonistic force preventing Richard from achieving his goal of finding the real killer.

A Character Who Is a Villain But Not an AntagonistIn American Psycho, Patrick Bateman is not only a terrifying serial killer but the protagonist. He is clearly evil and motivated to harm others, but the main antagonist working against him is Donald Kimball, a police detective and a good man, simply trying to solve a case.

Who is your favorite Villain or Antagonist? Why?

Neil Chase is a story and writing coach, award-winning screenwriter and actor, and author of the acclaimed horror-western novel, Iron Dogs. Neil believes that all writers have the potential to create great work. His passion is helping writers find their voice and develop their skills so that they can create stories that are both entertaining and meaningful. If you���re ready to take your writing to the next level, check out his website for tips and inspiration!

The post An Antagonist vs a Villain: What’s the Difference? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

July 30, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: Letting People Down

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental health condition, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc. Please note that this isn’t a self-diagnosis tool. Fears are common in the real world, and while we may at times share similar tendencies as characters, the entry below is for fiction writing purposes only.

Fear of Letting People Down

Fear of Letting People DownNotes

The feeling of letting people down is never a pleasant one, nor is it uncommon. Not wanting to disappoint or upset others is understandable���especially if it’s someone the character loves or is responsible for. The problem comes when this mindset becomes an obsession. This fear can come from a desire to please a parent, spouse, employer, friend, group, or even society as a whole. When pleasing people takes over, unhealthy patterns form, which lead to a whole host of problems.

What It Looks Like

Repeatedly asking for instructions

Asking to help (with chores, services, etc.) or doing these things without asking

Consistently receiving high grades or performance reviews

Working overtime often

Being a perfectionist

Volunteering to run errands, do favors, etc.

Constantly apologizing for little things

Being hurt by constructive criticism

Seeking validation and praise for work or services

Spending free time on pursuits that will make the character better (studying, volunteering, taking on an internship, etc.)

Obsessing over small details

Agreeing to plans with minimal hesitation

Being empathetic and sensitive to others’ emotions

Making sacrifices to put other’s needs first

Agreeing with others’ opinions, evaluations, and ideas

Being highly suggestible

Repeatedly assuring others when they make mistakes

Conforming to societal norms

Watching others carefully for negative reactions

Cheerfulness, even when doing menial tasks

Common Internal Struggles

Wanting to follow a passion (for a career, etc.), but caving to what others expect

Putting on an emotional front to hide “unacceptable” emotions

The character investing in a hobby they don’t enjoy because someone else likes it

Not knowing how to say no

The character feeling that they’re not enough

The character compromising their values to do what’s expected

Smiling on the outside while falling apart on the inside

Wanting to share an opinion but not wanting to cause trouble

Resenting the people the character is trying so hard to please, and feeling guilty about it

Worrying about the repercussions of falling short or making a mistake

Flaws That May Emerge

Cowardly, Defensive, Fussy, Inhibited, Insecure, Irrational, Martyr, Needy, Obsessive, Oversensitive, Perfectionist, Pessimistic, Self-Destructive, Subservient, Timid, Weak-Willed, Workaholic

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

Struggling to function at work or school due to fear of failure or making mistakes

Struggling with low self-esteem and depressive disorders

Feeling a lack of true connection to certain people (parents, a boss, etc.)

The character being unable to do the things that make them personally happy because they’re too busy doing what others want

Being taken advantage of due to a lack of personal boundaries

Constantly flirting with burnout

Frequently falling ill due to a lack of self-care

The character believing that their own opinions and ideas aren’t as important as other people’s

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

Receiving a poor grade or performance assessment at work

Being asked to do a large or difficult task

The character learning that someone wasn’t happy with their work

Having to make a crucial decision���e.g., marriage, attending college, choosing a career

Being punished or penalized for making a mistake

Someone critical or harsh re-entering the character’s life

Getting invited to two events at the same time and having to choose one

Being asked or pressured to do something the character isn’t comfortable with

A significant other not appreciating a thoughtful gift

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: Letting People Down appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

July 28, 2022

3 Medical Mistakes to Avoid in Your Story

By Natalie Dale, MD

As a former physician, I get a lot of questions from other writers about medical aspects of their stories. And while every story is unique, there are a few mistakes writers seem to make over and over. Below are three of the most common mistakes, along with suggestions on how to avoid them.

1. Passing Out from Blood LossThe mistake:

Your character is injured in a fight and they���re losing blood, fast. Then the world goes black. They wake up some time later, woozy but otherwise fine, with a bandage slapped over the wound.

Why it���s wrong:

If your character is bleeding out fast enough to pass out, they���re bleeding out fast enough to die. The average human contains about five liters (5L) of blood. The amount of blood they lose, and how fast they lose it, will dictate their symptoms.

10% blood loss (0.5L): Minimal symptoms20% blood loss (1L): Anxiety, dizziness, and blacking out when going from lying down to standing up (called orthostatic hypotension)30% blood loss (1.5L): Low blood pressure, racing pulse, and fast breathing rate, feeling woozy/drowsy, having difficulty focusing. Also called hemorrhagic shock.40% blood loss (2L): Loss of consciousness50% blood loss (2.5L): Death

It doesn���t take much to go from unconscious to dead. If you want your character to pass out from blood loss���and survive���they���ll need some sort of intervention to stop the bleeding. And no, slapping a bandage over the wound won���t cut it.

How to fix it:

Get your character medical care, such as surgery, blood products, and pressors, soon after they fall unconscious. If that isn���t possible, consider having them pass out from pain or from the sight of their own blood, rather than from the blood loss itself.

2. The Harmless Head InjuryThe mistake:

Your protagonist has subdued her nemesis; all she must do now is get rid of him. But she���s the good guy���she can���t kill him. So, she knocks him unconscious instead. He wakes up an hour or so later with a mild headache and a burning desire for vengeance.

Why it���s wrong:

A hit to the head that causes unconsciousness is a traumatic brain injury, or TBI. TBIs are major injuries, with lasting consequences ranging from daily headaches to coma and death. Here���s a brief guide to the symptoms your character should exhibit based on the duration of their unconsciousness.

No loss of consciousness: Mild-moderate concussion. Concussion symptoms include headaches, dizziness, ringing in the ears, trouble concentrating, short-term memory problems (posttraumatic amnesia), and behavior changes that last from several hours to a few weeks.Brief loss of consciousness (seconds to 30 minutes): Severe concussion or epidural hematoma, a potentially fatal type of brain bleed. If your character has a concussion, they will have severe concussive symptoms (see above) lasting days to months. If they have an epidural hematoma, your character will briefly pass out, then wake up and insist they���re fine. But watch out! As they continue to bleed into the space between their brain and skull, your character will get progressively drowsier and more incoherent, until they fall asleep. If they don���t get neurosurgery to stop the bleed, they���ll die.Up to 6 hours unconscious: Moderate TBI. Requires hospitalization and often ICU admission. After their hospitalization, your character will require weeks to months of intensive rehabilitation to recover. If your character doesn���t receive treatment, they may die.More than 6 hours unconscious: Severe TBI. Your character will require treatment in the ICU. If they survive���and many don���t���they will probably suffer from lifelong disability. Full recovery from a severe TBI is exceedingly rare.How to fix it:

Unfortunately, there is no safe way to instantaneously knock someone unconscious, keep them unconscious for any appreciable amount of time, then have them wake up and be totally fine. It���s a buzzkill, I know. But there are ways you can make it work.

Hit them over the head and give them a concussion: If your story needs your character to be immediately knocked unconscious for a few minutes, you can get away with it. Just keep the duration of unconsciousness to under 30 minutes and give them signs of a concussion afterwards.Give a sedative: If your story needs a character to be knocked out for a while, consider giving them a sedative like midazolam (Versed). Intravenous (IV) administration would start working fastest but can���t be given quickly. Intramuscular (IM) injections, on the other hand, can be given in as little as 2-4 seconds. Because they���re so easy to give, IM sedatives are often used by paramedics and psychiatrists on severely agitated patients. Once injected, these medications will take 15-30 min to take effect, but once it does, the character will be reliably asleep for up to 90 minutes.3. The Mythical “Medically Induced” ComaThe mistake:

Your character has been grievously injured, so they are put in a medically induced coma to heal. They���re on the brink of death and the family/police can���t talk to them, so no one really knows what happened. All they can do is wait and pray your character will be OK.

Why it���s wrong:

People aren���t put into comas to heal. In fact, therapeutic comas (the medical term for ���medically-induced coma���) are used only in two very specific situations. But first, let���s talk definitions.

A coma is a prolonged state of unresponsiveness, meaning that your character isn���t responding at all to their environment. Coma isn���t a diagnosis; there are lots of things that can cause a coma, ranging from drug overdose to TBI. If your character is in a coma, it means their brain has suffered a big enough insult that it needed to shut down some of its most basic functions. The prognosis of a coma depends on both its cause and duration. But for the most part, if your character is in a coma, they are going to have a very long road to recovery.

A therapeutic coma is when doctors give your character medications to artificially depress brain function so completely that your character becomes comatose. Doing so is quite dangerous; your character will need to be intubated and put on a ventilator to breathe for them, and their vital signs���particularly blood pressure���will need to be closely monitored. Because it���s so dangerous, your character will only be put into a therapeutic coma if doctors need to shut down all brain activity. And there are only two reasons for this: unrelenting seizures (refractory status epilepticus) and increased pressure inside the skull (increased intracranial pressure) due to brain swelling, bleeding on the brain, or a fast-growing brain tumor. These conditions are exceedingly dangerous and have a terrible prognosis. If you want your character to fully recover from their injuries, I highly recommend avoiding the therapeutic coma.

How to fix it: ��

Luckily, there is an easy solution: ventilation and sedation.

If your character has been seriously injured, they might need to be put on a ventilator to help them breathe. Reasons for needing a ventilator range from traumatic chest injuries, like flail chest or pulmonary contusion, to pneumonia. Ventilators are notoriously uncomfortable���many people who���ve been on a ventilator get PTSD from the experience���and so ventilated patients are usually kept at least minimally sedated.

Unlike comas, the prognosis of recovery after sedation is excellent. The medications can be reversed or just given time to make their way out of your character���s system, and they���ll wake right up. Ventilation and sedation provide all the tension of a life-threatening injury���and the inability to communicate���without the horrible prognosis of the medically induced coma.

Final ThoughtsWhat we write matters. Though it may seem like nitpicking to insist that you sedate your character instead of putting them in a medically induced coma, or give your character symptoms of a concussion after their head injury, I assure you that it���s important. There are real people out there suffering from these conditions and how we, as writers, portray these conditions can make a real difference.

Natalie Dale, MD, is a former neurologist turned writer and medical story consultant. Her ���Writer���s Guide to Medicine��� series currently has two volumes published through Ranunculus Press. Volume 1: Setting & Character was released in 2021, and Volume 2: Illness & Injury recently launched in July 2022. Dr. Dale also has essays and short stories published through The Bump, National Alliance on Mental Illness, Wyldblood, and Downstate Story, among others. To find out more, check out her website or follow her on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.

The post 3 Medical Mistakes to Avoid in Your Story appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

July 26, 2022

The Dreaded Synopsis

By Michelle Barker

Many authors would rather write a whole new novel than cram the one they���ve already written into a five-hundred-word summary. If I wanted to write a short story, I would have written one. Right?

The reason we hate writing synopses is because they���re hard. The reason they���re hard is because, more than any other tool available to us, they show us what���s wrong with the novel we���ve labored over for months, if not years.

The synopsis is the equivalent of a house inspector���that man or woman who walks around with a clipboard and goes through the house you thought you were ready to sell, pointing out all the structural issues you either didn���t know about or pretended weren���t a problem: roof damage, termites, a saggy bearing wall, you name it. You can do all the fancy writing in the world. If there���s something fundamentally wrong with your novel, it will come out in the synopsis.

That���s why we hate them.

That���s why most agents ask for one.

Reading a synopsis is the quickest way to know if a novel will work or not. It���s also the surest way to find out if the author knows what they���re doing when it comes to things like structure, causality, story arc and characterization���you know, those critical developmental issues you hoped wouldn���t matter.

Guess what? They do.

If your plot is anecdotal, it will show up in the synopsis. If your protagonist doesn���t have a goal that they���re actively pursuing throughout the story; if there are no stakes, a weak antagonist, a plot that���s bursting with too much superficial business and no depth���yup, the synopsis will reveal all of that.

If you, the author, are willing to see it, the synopsis will be that heart-sinking moment of truth where you can no longer deny that this house is not ready to sell, not by a long-shot. It needs help. It might even need to be razed to the ground.

Too extreme, you say? Well. Most published authors I know (myself included) have had to do it on numerous occasions. If you believe John Green, he does it with every one of his first drafts, throws out ninety percent, right down to the foundation, and starts over.

What do most new authors do? Close their eyes and send out the query as is, along with that stinky synopsis, hoping no one will notice.

They���ll notice.

If you wonder why your novel is getting rejected time and again, now you know. Even if the premise is great���which it may well be���if you can���t execute it because of developmental issues, forget it. No one will ask to read it.

This is harsh. It���s not what writers want to hear. But it���s the truth.

So���what to do about it?

Learn About Novel StructureThere are many great craft books that can teach you novel structure, and numerous workshops, classes, and conferences you can take. You can also hire an editor or even a writing coach to sort through these issues with you. In all of these cases, you���ll come away with skills that you���ll be able to rely on for the rest of your career.

Here are tons of tools to strengthen your plot and structure…including step-by step help while you plot with the Storyteller’s Roadmap.

Reverse the ProcessWrite the synopsis first.

In case you���re wondering: no, writing the synopsis first isn���t much fun, either. It���s way more enjoyable when you have that first ping of an idea to sit down and start writing the novel right away. I know. I���ve done it. And then you hit ten thousand words or so and suddenly it���s not so fun anymore. You���re stuck. You���ve written yourself into a corner that you can���t get out of because you haven���t thought about structure, or goals, or stakes.

The trick is to think about these things before you start writing.

How detailed you get about this pre-emptive synopsis is up to you. Personally, I like to know the big plot points but allow the finer details to emerge in the creative process of the novel itself, but there are writers who take a scene-by-scene approach. There���s no wrong way to do it. What you want to make sure you do, however, is list the essential structural elements of a novel and make sure you know what each of them will look like in your story. You���ll also want to make sure your protagonist���s goal is clear, specific, and quantifiable, and that the reader knows in the end whether the protagonist got what they wanted.

If your great idea turns out not to work at the synopsis stage, all you���ll lose are a few pages of work���as opposed to a three-hundred-page clunker of a novel. It���s also far easier to pinpoint where it���s not working at the synopsis stage and figure out how to fix it. When you���re deep into the novel, that���s a much more difficult thing to see. Usually by that point, you���ll need a dev editor to see it for you���and by then you���ll be so attached to your work (and all the time you���ve sunk into it), that you���ll be less inclined to listen to them when they tell you you need to start over.

Save yourself the heartache of rejection. Start at the end and give yourself a solid foundation to work with. Then, when it comes time to send out the synopsis, you���ll already have it done and will be confident that your house is sound and ready to sell.

Here are two posts to help you write a great synopsis:

Synopsis Writing Made Easy

A Cheat���s Guide to Writing a Synopsis

Michelle Barker is the award-winning author of The House of One Thousand Eyes. She is also a senior editor at darlingaxe.com, a novel development and editing service.

Her newest novel, My Long List of Impossible Things, was released in 2020 with Annick Press. You can find her on Twitter, Instagram, and her website.

The post The Dreaded Synopsis appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

July 22, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: Leaving No Legacy

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental health condition, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc. Please note that this isn’t a self-diagnosis tool. Fears are common in the real world, and while we may at times share similar tendencies as characters, the entry below is for fiction writing purposes only.

Fear of Leaving No Legacy

Fear of Leaving No LegacyNotes

There are different kinds of legacies. Sometimes, it’s accumulating something substantial, such as money or land, for one’s children. In other cases, a legacy is a worthwhile accomplishment that will be remembered after the character’s death. Legacy is often tied up in purpose, resulting in a character with this fear going to any length to leave their mark and prove that their life had meaning and substance.

What It Looks Like

Being ambitious

Accumulating wealth or status (degrees, membership in exclusive clubs, etc.)

Protecting the legacy above all else

Overspending to impress the right people and win recognition

Having high expectations (for themselves and/or others)

The character focusing intensely on whatever path will make their legacy a reality

Passionately pursuing creative endeavors and acclaim

Donating significant amounts of money to charities, hospitals, or the arts

The character pushing their own children toward financial or creative success

Volunteerism

Keeping meticulous records and photos for posterity

Making emotional decisions (instead of logical ones) surrounding the legacy

Using unethical means to keep others from blocking the character’s pursuit

Common Internal Struggles

Feeling guilty for missing family milestones in pursuit of the legacy

Wanting to leave a legacy despite knowing it won’t last forever

Grappling with the fear of dying without having left a mark

Seeing an opportunity that will give the character what they want, but knowing that others will be harmed by it

The character fearing they’ll never do enough to establish their legacy, no matter how hard they work

Being tempted to use unethical means to reach the goal

Wanting to build some kind of legacy but not knowing what it should be

Worrying about who will continue the legacy when the character is gone

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

An inability to balance the legacy with other areas of life

Missing important family events because of the character’s single-minded dedication to the legacy

Being unable to enjoy life outside of the legacy

Competing with friends and siblings (to earn more money, be more successful, etc.)

Living with regret over things and people the character sacrificed in pursuit of the legacy

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

Seeing someone fade into obscurity after their death

The character’s parent dying with nothing to leave for their heirs

A long-standing record of the character’s being broken

The character being unable to overcome an obstacle threatening their legacy

Having to declare bankruptcy

The character falling dangerously ill and not wanting to leave only debts for their children

The character being told that nothing they do matters

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: Leaving No Legacy appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

July 20, 2022

Phenomenal First Pages Contest

Hey, wonderful writerly people! It���s time for our monthly first-page critique contest

Hey, wonderful writerly people! It���s time for our monthly first-page critique contest

If you���re working on a first page (in any genre except erotica) and would like some objective feedback, please leave a comment. Any comment :). As long as the email address associated with your WordPress account/comment profile is up-to-date, I���ll be able to contact you if your first page is chosen. Just please know that if I���m unable to get in touch with you through that address, you���ll have to forfeit your win.

Two caveats:

Please be sure your first page (double-spaced in 12-point font) is ready to go so I can critique it before next month���s contest rolls around. If it needs some work and you won���t be able to get it to me right away, let me ask that you plan on entering the next contest, once any necessary tweaking has been taken care of. Resources for common problems writers encounter in their opening pages can be found here.

Please be sure your first page (double-spaced in 12-point font) is ready to go so I can critique it before next month���s contest rolls around. If it needs some work and you won���t be able to get it to me right away, let me ask that you plan on entering the next contest, once any necessary tweaking has been taken care of. Resources for common problems writers encounter in their opening pages can be found here.

This contest only runs for 24 hours, start to finish, so get your comment in there!

This contest only runs for 24 hours, start to finish, so get your comment in there!

Three commenters��� names will be randomly drawn and posted tomorrow morning. If you win, you can email me your first page and I���ll offer my feedback.

We run this contest on a monthly basis, so if you���d like to be notified when the next opportunity comes around, consider subscribing to our blog (see the right-hand sidebar).

Best of luck!

PS: If you want to amp up your first page, grab our helpful First Pages checklist from One Stop for Writers. And for more instruction on these important opening elements, see this Mother Lode of First Page Resources.The post Phenomenal First Pages Contest appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

July 19, 2022

Identify Your Character���s Emotional Triggers

By Lisa Hall Wilson

Every one has emotional triggers ��� are you using this to increase the emotional tension in your story? Why not!?

What Does Your Character Think is Their Strength?What does your character pride themselves on having, being, doing, possessing, needing, controlling, etc? Do they rest their identity in any of these things? Some common ones are: acceptance, respect, being liked, being needed, freedom, attention, being in control, autonomy, safety, etc.

It could be a strength or aptitude that was reinforced when they were young. A child identified as gifted at a young age might place all their identity and self-worth in being smart, in being the smartest person in the room. How would they feel when faced with a new colleague who is smarter, faster, more innovative? What would that do to their self-confidence?

This where personality plays into things. Would they react in anger and lash out, gossip, try to undermine the new colleague at every opportunity? Would they sink into shame and beat themselves up constantly? Would they become competitive and work themselves into the ground to maintain what they believe they���re owed or due?

A woman who���s always told how pretty she is might begin to expect that compliment from people, from men in particular. What thought takes root if that doesn���t happen? What emotions come to the fore if she���s in the room when another woman gets all the compliments and not her?

Emotional triggers are often linked to anything a character feels they���re really good at, that they deserve, something they see as their personal identity, or that they���re constantly striving for (feeling heard by a spouse for example).

What Does Your Character Value Most and Fears Having Taken Away?This is where the primary and secondary emotions come into play. You can read more about that here ��� but to recap a primary emotion is an instinctive emotional response: fear, guilt, envy, jealousy, attraction. A secondary emotion is any emotion that requires a thinking response: love, anger, hatred, shame, etc.

Anger and shame and love are always secondary emotions.

Some emotions can be either a primary or secondary emotion. For example, attraction can be an instinctive thing (a primary emotion), but it can also develop over time with familiarity (a secondary emotion).

An emotional trigger skips the primary emotion phase and jumps right to the thinking response ��� the secondary emotion. That���s why you can instantly be angry at something and not know why.

So, for example, I have a character with an emotional trigger of feeling high maintenance. If she perceives that people think she���s being high maintenance, too-big-for-her-britches, because it���s a learned response (one that she���s practiced many times) she skips right to feeling shame. The shame is what���s observable (showable in actions or dialogue). The shame is what I show when writing this emotional trigger.

What Emotions Are Activated When Key Needs Are or Aren���t Met?

Activated is another way to say triggered, but in this context it seems more descriptive. Once you���ve identified the feelings or fears that are emotional triggers for your character (and yes you can have more than one), figure out what emotions are activated when that situation crops up.

You have to think in terms of secondary emotions here. Do they immediately become angry? Are they riddled with shame? Do they feel loved? Remember, triggers don���t have to be negative!

Now, to manage or overcome an emotional trigger, an individual needs a good measure of self-awareness and humility. Then, as Brene Brown would say, they need to get curious. Why do they feel that way? What do they feel is at stake?

How to Show and Not Tell an Emotional TriggerIn my Method Acting For Writers Masterclass, I talk about how primary emotions are usually felt and secondary emotions are usually seen. How does that play out?

Eliza���s husband is three hours later coming home than he said he���d be, without answering texts, emails or phone calls to explain the delay. Eliza has shipped the kids off to grandma���s for the night, prepared a nice dinner, and gotten all dressed up ��� as a surprise.

By the time hubs arrives home, Eliza has cleared the romantic setting from the table, put all the still-edible bits of food in the fridge, and Eliza���s changed out of the sexy outfit she���d been wearing into a terry bathrobe.

During the whole clean-up, her primary emotions are going wild. Frustration (feeling taken for granted). Concern (did something happen at work). Fear (was he in an accident). Jealousy (was there another woman). You���d show all these emotions colliding around inside through physiology, actions, and internal dialogue.

Once hubs arrives home and is safe ��� oh, whoops ��� went out for drinks did I forget to text you? Now she has to DO something with these emotions so now she���s angry. But if Eliza had an emotional trigger of say��� feeling in control, then not knowing where her hubs was when he was supposed to be at home would be a trigger for a secondary emotion. Having her well-thought-out plans for the surprise would be an emotional trigger.

Emotional triggers can be powerful and effective, because they���re so often over-the-top emotional reactions. When your emotional triggers are activated, you���re not just angry ��� you���re livid. People can observe these night-and-day emotional hairpin turns. They seem to come out of nowhere if you���re not privy to what the trigger is.

Are you using emotional triggers in your novel?What is your character afraid will be taken away or threatened?

Lisa Hall-Wilson

Lisa Hall-WilsonResident Writing Coach

If Lisa had a super-power it would be breaking down complicated concepts into digestible practical steps. Lisa loves helping writers ���go deeper��� and create emotional connections with readers using deep point of view! Hang out with Lisa on Facebook at Confident Writers where she talks deep point of view.

Twitter �� Facebook �� Website �� Pinterest

The post Identify Your Character���s Emotional Triggers appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

July 16, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: Isolation

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental health condition, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc. Please note that this isn’t a self-diagnosis tool. Fears are common in the real world, and while we may at times share similar tendencies as characters, the entry below is for fiction writing purposes only.

Fear of Isolation

Fear of IsolationNotes

As social beings, it’s common for human beings to seek out others for support, companionship, or safety. But alone time is also important for people to be able to rest, reflect, and recharge. And no matter how social a character is, there will be times when they’re on their own and need to be comfortable with themselves as company. A character with a fear of isolation will struggle in these moments due to the intense discomfort that arises when they’re alone.

What It Looks Like

Having a large family

Pursuing a public career or one that requires the character to interface with others

Living in a highly populated area

Having an overly active social life

Always having a significant other

Being in multiple romantic relationships simultaneously

Flourishing in large groups of people

Being the one who coordinates get-togethers

Keeping the TV on all night as background noise

Working in an office rather than remotely

Calling people often to chat

Being the last one to leave the party

Making do with surface-level relationships when deeper ones aren’t available

Common Internal Struggles

Needing downtime to decompress but not wanting to be alone

Being stressed by a packed social calendar yet continuing to fill it

The character fearing their inner thoughts and emotions when they’re alone

The character fearing they cannot take care of themselves on their own

Negative thoughts and feelings taking over in the absence of other people

Feeling anxious, unsafe, or panicky when alone

Being assaulted by inner demons and bad memories when no one is around

Flaws That May Emerge

Abrasive, Addictive, Compulsive, Controlling, Frivolous, Impulsive, Insecure, Melodramatic, Needy, Obsessive, Possessive, Pushy, Self-Indulgent, Vain, Volatile, Workaholic

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

The character being unable to enjoy time alone and in their own company

Having more shallow friendships than deep and personal ones (because the character is flitting from one group of people to another)

Engaging romantically with people who aren’t a good fit simply because they’re available

Past pain going unresolved because the character won’t face it

Being over-scheduled

Using drugs, food, or alcohol when alone to combat anxiety

The character frequently annoying others by always intruding on their time

Suffering from exhaustion

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

A horrible secret or memory surfacing during a quiet moment alone

Getting lost and being alone for longer than usual

Being dumped and having a lot of disposable time

A pandemic or environmental disaster triggering a lockdown or quarantine

Seeing someone suffering alone with the same issue that plagues the character (depression, anxiety, wrestling with a similar wounding event, etc.)

Plans falling through, leaving the character on their own

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: Isolation appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1022 followers