Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 47

October 14, 2022

Less Is More���When It Comes to Describing Setting��

By C. S. Lakin

If you���re writing fiction, it���s your job to create rich, descriptive settings in which your characters live and breathe. The challenge���as any seasoned fiction writer can tell you���is how to find the proper balance between over- and under-describing, between extensively showing the setting with sensory details and briefly summarizing.

With fiction, it���s best to take a ���Goldilocks��� approach���not too much, not too little. But how can we find that place where the amount of description is ���just right���?

Renown writing instructor Sol Stein wrote,

���Writing fiction is a delicate balance. On the one hand, so much inexperienced writing suffers from generalities. ��� When the inexperienced writer gives the reader detail on character, clothing, settings, and actions, he [robs] the reader of one of the great pleasures of reading: exercising the imagination. My advice on achieving a balance is to ��� err on the side of too little rather than too much. For the reader���s imagination, less is more.��� (Stein on Writing)

Learning to find the balance between too little and too much description takes time, practice, and study.

Study is the most important of the three elements because that is how you will learn masterful technique���examining how expert best-selling authors in your specific genre wield description so that readers are transported into the imaginative world created without suffering from boredom, irritation, or confusion.

How to Find the BalanceHow can writers understand the advice of ���less is more��� in a practical sense? Pull out a novel you love (in your genre) and find passages of setting. (Though it helps to look at current best sellers, it���s really not important when it comes to great setting description. I���ve found Zane Grey���s spectacular setting descriptions, written in the early 20th century, highly instructive for me when I write my historical Westerns, aiming to capture the sensory flavors that he did so masterfully.)

Often you���ll find that just 3-4 sensory details will convey a sense of place. But whatever detail is shown must be filtered through the POV character���s senses. To be believable, what she sees, feels, hears, or experiences of her surroundings must be things she would notice in that moment. And the few lines of description need to reflect her mood and mind-set.

This is critical. Any setting description out of POV and not in the right mood is too much (and, often, just plain weak writing). Why is it too much? Because hardly anyone ever looks around them and makes a mental list of every single thing they can see.

All this means you need to be clear on what your character is thinking and feeling at any given moment. And you need to keep the purpose of your scene at the forefront of your thoughts when considering how to describe setting.

I recall during a master class I took at Thrillerfest a few years back when my instructor spoke enviously about how another writer described New York City in one sentence. As the fictional character went out for his morning run, he passed the overstuffed black trash bags spilling off the corners of the streets at dawn on trash pickup days, noticing how the bags wiggled as the rats inside scrounged for food. To him, it was the perfect iconic description of setting in one line. Nothing else needed to be said to set the mood.

Here are some examples of setting up a sense of place with just a few specific, carefully chosen sensory details (in POV):The attic was pleasantly chilly and smelled of pine. Decades of summer heat have forced droplets of resin out of the rough floorboards, which in cooler weather hardened to little amber marbles that scattered in all directions as we shifted trunks and cardboard boxes. The afternoon is fixed in my memory with the sharp smell of resin and that particular amber rattle, like the sound of ball bearings rolling around in a box. It���s surprising how much of memory is built around things unnoticed at the time. (Animal Dreams, Barbara Kingsolver)

Across the yard the mound of bike parts glistened with the early morning wetness that I���d always heard was angel tears. Some of the sprockets stared at me, their gaping eyes rimmed with metal eyelashes. It could have been a postmodern sculpture. ���In New York you���d fetch big bucks,��� I told it.

Walking would warm me. I crossed the rickety bridge that spanned the creek and started off toward the road to town. I pumped my arms, striding briskly along the rutted lane, where evergreens, withered and skeletal, blended into the gray green of the sage. Tiny had said the trees were infested with a kind of beetle, killing them an inch at a time. This saddened me and I walked faster. (The Fence My Father Built, Linda S. Clare)

I walked back out to my car. The scrub oak on the rim of the hills looked like stenciled black scars against the molten sun. I started the car engine, then turned it off and got back out and slammed the door. (Bitteroot, James Lee Burke)

I hope you noticed how personal these descriptions are, the setting telling something about the POV character and not just blandly presenting a laundry list of adjectives and nouns.

With the last example, the setting comes through simple action���the character walks to his car, gets in, starts and cuts the engine, gets out. Without knowing anything about this moment in the story, it���s clear what the character���s mood and mind-set are by the choice of verbs and adjectives. Burke also uses a simile to convey that mood���a great technique to use to drive home emotion.

He doesn���t overdo it with lengthy, wordy descriptions of how the character is feeling. The man doesn���t stride angrily, stomping his feet as he goes to his car. He merely looks out at the horizon in a moment of contemplation. We sense he���s trying to decide whether to stay or go. He doesn���t rev the engine, grip the steering wheel with whitened knuckles as he grits his teeth. He doesn���t describe the temperature in the car, what the road looks like, or the smell of the exhaust.

Yes, Burke could have added a few more lines, deepened the mood, slowed things down further, and it would have been effective. But ��� less is more. And, as you can conclude, less results in strong pacing, keeping the action moving without dawdling and boring readers.

PracticeTake a moment and freewrite a setting your character finds herself in. If you can choose one from your current project, all the better.

First, consider the purpose of the scene. Why your character is in this particular place and what she is doing there. What mood is she in and why? Write about the setting from her POV and in her mood. Make sure every noun, verb, and adjective reflects her mood. Fill a whole page with all kinds of sensory details.

Now, select just three or four phrases, sentences, or similes that really nail the setting in her POV. If you do this every time you sit down to write a new scene or put your character in a new place, you���ll get the hang of ���less is more.��� And your writing will greatly improve.

Want to master crafting powerful settings? Enroll in C. S. Lakin���s new online video course that will give you technique and exercises to evoke settings that will immerse your readers. Enroll before October 24, 2022 and get 30% off with coupon code EARLYBIRD.

C. S. Lakin is an award-winning author, blogger, copyeditor, and writing coach. She has taught thousands of writers how to improve their craft through her blog, Live Write Thrive, and her online school. She is the author of the Writer���s Toolbox series of books on novel writing and does more than two hundred manuscript critiques a year.

You can find all her online courses for fiction writers at Writing for Life Workshops on teachable.

The post Less Is More���When It Comes to Describing Setting�� appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 12, 2022

The Key to a Successful NaNoWriMo? Using October Wisely

Are you one of tens of thousands of intrepid writers participating in NaNoWriMo? If so, know this: you’re a rock star. Writing a novel is something many people talk about doing, but few actually do it. And here you are, pulling out your keyboard to enter the challenge of completing a novel in a month!

If NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) is new to you, think CHALLENGE meets CREATIVITY. Writers all over the world set the same goal: to write 50,000 words in the month of November. That’s a boatload of words, and for many, adds up to a full novel. But whether a person reaches 50K or not, participating is a way to silence the ‘ol You can’t write a novel! jerk-voice in their head and just write. (Fun Fact: my first full-length novel was a NaNo novel.)

This challenge is a great time to experiment: try a new genre, play with ideas, and let creativity take the wheel. But don’t mishear me – giving over to creativity doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do any story planning and instead assume the muse will show up on November 1st.

In fact, the key to a successful NaNoWriMo is to use October to plan and prep!To be ready for a full month of intense writing bursts, we should know a few things about what we’re writing, and have a plan on how to get to our 50,000 word goal.

Plan the story…Whether you are a plotter or a pantser, it’s generally not good to start NaNoWriMo with no idea what to write about…unless you are looking to experiment, pressure-free, and won’t sweat it if you get lost or stuck, or finishing is not a big deal. But for the majority, having some direction at the start means starting off well, and it’s easier to build momentum so the words continue to flow.

Pantsers should have some idea of the type of story they want to write, and know a bit about what might happen. It can be a looser plan where characters and plot are more impressions, and who they are and what will happen in the story will be discovered as they write.

Plotters will want to do a deeper level of planning, including building characters to understand their personality, backstory, needs, goals, and more so it’s easier to write their actions and choices in the story. They’ll also want to plot or outline so they have a firmer idea of where their story will go and some of the major events that will happen. World building is also something to spend time on so it’s easier to draw readers into the character’s reality.

TIP: Whether you plot, plan, or do something in between, download the Ultimate NaNoWriMo Prep Guide below. You’ll be so glad you did.

Plan your time…

One of the biggest reasons why writers fail to finish NaNoWriMo is because life takes over and they can’t carve out enough time to write. Looking ahead to November and what might be happening in your life then can help you see what will be competing for your time. Maybe there will be some things you can handle now, or you can proactively plan for so they aren’t as disruptive. It’s also a good time to sit down with family members to explain how they can help you achieve your goal, and how that certain times they’ll need to step up because you won’t be available.

Plan your toolkit…There are plenty of resources that can make it easier for you to know what to write, focus on the task at hand, supply you with ideas when you need them, and support you in other ways. Bookmark these babies:

NANOWRIMO: Seems obvious, I know, but there’s a ton of support right at the NaNo site, and you don’t want to miss it. So, sign up, introduce yourself on the forums, find local groups, and explore the many resources that writers all over the world recommend. (Don’t forget to recommend the ones that help you, too!)

TRELLO: This free tool is great for brainstorming. Gather together story ideas, research links, create columns for each character…Trello’s drag-and-drop cards are a great way to organize your ideas.

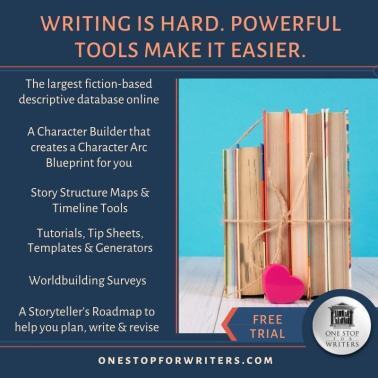

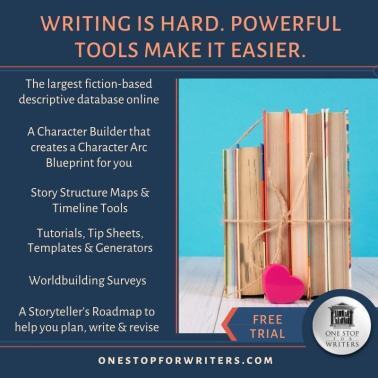

ONE STOP FOR WRITERS: This creativity portal is LOADED with powerful resources to help you plan characters & their arcs, world-build, create timelines, outline your story, and have non-stop ideas on tap so you always know what to write next. Start with a 2-week free trial if you like, or take advantage of this birthday discount.

TIP: While you’re at One Stop, poke around the THESAURUS to see all the way you can bring out your freshest stories ideas. The Conflict Thesaurus may become your best friend!

BRAIN FM: I purchased a lifetime license years ago and have never looked back, and why? Because it helps me focus on the task at hand. This app plays special neural phase-locking music that engages with your brain, encouraging productive writing sessions. If you’d like to try it, use my member’s code to get a free month.

FREEDOM: If social media and email pings distract you, well, you aren’t alone. An unending stream of information is a blessing and a curse, so if you want to claw back your keyboard, try this app and website blocker. (There’s a free trial).

THE NOVELIST’S TRIAGE CENTER: If you write yourself into a corner, run out of ideas, a plot hole happens, etc., visit this page. It’s packed with the many possible problems you might encounter and how to free yourself of them so the words continue to flow.

ULTIMATE NANOWRIMO PREP GUIDE: Wondering what story elements you really need to plan to be ready for November, and the other things you can do now that will set you up for a great NaNoWriMo?

Everything you need to for a successful NaNoWriMo is in this handy guide.

It’s full of actionable ideas on how to make time to write, plan as much or as little as you need, and points you to ingenious tools and resources that can help you.

Plan in October, slay it in November!Mindy, Becca, and I have our pom-poms ready to cheer you on. You’ve got this!

The post The Key to a Successful NaNoWriMo? Using October Wisely appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 11, 2022

The Skeleton of Your Story

Think of Milestones (aka story beats) as a human skeleton. The skull, spine, sternum (breastbone), scapula, ribs, and pelvis are vital for life. Without these large bones in place, we���d become a mushy blob of skin, muscle, and meat. Also important is the humerus (upper arm), radius and ulna (forearm), femur (thigh), patella (knee), tibia and fibula (shin). Though we could survive without arms and/or legs, we���d have to adjust to a new way of life. Same is true for the metatarsals and phalanges of our hands and feet.

A complete skeleton has the strongest foundation. Don���t we want the same for our novels?

Drilling down into the Three Act Structure, the dramatic arc is split into four quartiles. Milestones appear on the microlevel of those quartiles, called Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV. Each Part takes up about 25% of the novel. For clarity, I���ve colored Acts in red, Parts in blue, Milestones in black.

Ready to get high on craft? Cool. Let���s do this���

ACT 1 Part I: The Set Up:The first quartile (25%) of the story has but a single mission: to set-up everything that follows. We need to accomplish a handful of things (as you���ll see in the Milestones), but they all fall under the umbrella of that singular mission. If we choose to show the antagonist, we only want to include jigsaw pieces of the puzzle.

Most importantly, Part 1 needs to establish stakes for what happens to the hero after Part 1. Here in Part 1 is where the reader is made to care. The more we empathize with what the hero has at stake���what they need and want in their life and/or what obstacles they need to conquer before the arrival of the primary conflict���the more we care when it all changes.

In Part 1 the hero is like an orphan, unsure of what will happen in their life. And like orphans, we feel for them. We empathize. We care.

Opening Scene

Often the Opening Scene doubles as the Hook, but not always. If you choose to include a prologue, for example, the Opening Scene must also hook the reader.

Hook

In an 85K word novel, the Hook should arrive between p. 1-15. This scene should introduce the hero, hook the reader, and entice them enough to keep reading. You need to ensure the reader either relates to, or empathizes with, the main character. Contrary to what some believe a reader does not have to like a main character. There have been plenty of unlikable heroes that have hooked us for an entire novel. Why? Because we empathized with their situation. Likeable or unlikeable, the reader must have a reason to root for them. That���s key.

Inciting Incident *Optional*

Not every story has to have an Inciting Incident in the way I use the term. Some call the Inciting Incident the First Plot Point. I refer to it as a separate Milestone, a foreshadowing of the First Plot Point but without affecting the protagonist. And that���s the main difference. It can even be an entirely different event, one that relates to the main plot, but it���s a false start. A tease. If we choose to include a separate Inciting Incident, this Milestone should land between p. 10-60 in the same 85K word novel. But an Inciting Incident does not mean we can skip the First Plot Point.

First Plot Point

Here���s where the true quest begins. The First Plot Point should land at 20-25% into the story, or between p. 60-75 in the 85K word novel. The First Plot Point is the single most important scene of all the Milestones because it kicks off the action and propels the hero on a quest, which is your story. Even if it���s been foreshadowed or hinted at, the First Plot Point shows the reader how it affects or changes the protagonist.

ACT 2 Part II: The Response :This quartile shows the protagonist���s reaction to the new goal/stakes/obstacles revealed by the First Plot Point. They don���t need to be heroic yet. Instead, they retreat, regroup, and/or have doomed attempts at a resolution.

First Pinch Point

The First Pinch Point arrives at about 37.5% into the story (roughly the 3/8th mark or p. 114 in the 85K word novel). This Milestone reveals a peek at the antagonist force, preventing the hero from reaching their goal. If you showed the antagonist earlier, this is a reminder, not filtered through narrative or the protagonist���s description but directly visible to the reader.

For a more in-depth look at Pinch Points, see this post.

Midpoint Shift

The Midpoint Shift lands smack dab in the middle of the story at 50% or on p. 152 in the 85K word novel. This is a transformative scene, a catalyst for new decisions and actions. With new information, awareness, or contextual understanding, the protagonist changes from wanderer to warrior, attacking the problem head on, which lays the foundation for Part III.

Part III: The Attack:Midpoint information, awareness, or contextual understanding causes the protagonist to change course���to shift���in how to approach the obstacles. The hero is now empowered, not merely reacting as they did in Part II. They have a plan on how to proceed.

Second Pinch Point

Unlike the First Pinch Point, we must devote an entire scene to this Milestone. The Second Pinch should land around the 5/8th mark or 62.5% into the story (around p.190 in the 85K word novel). This time, the antagonist is more frightening than ever because, like the hero, he���s upped his game. Or, if the antagonist force is Mother Nature, the Second Pinch Point shows the eye of the hurricane or lava erupting from a dormant volcano.

Dark Night of the Soul

A slower paced, all-hope-is-lost moment before the Second Plot Point, also known as the second plot point lull. At its heart, the Dark Night of the Soul is the main character grappling with a death of some kind���a mentor, profession, a relationship, his reputation, her sense of who she is, etc. Here���s where the hero is at their lowest point, believing they���ve failed.

As a clich��d example, the Dark Night of the Soul shows the cop with his gun in his mouth, ready to commit suicide. But then something happens to change his mind, and that something sets up our next Milestone.

Second Plot Point

The Second Plot Point arrives at 75% of the way into the story, or around p. 228 in the 85K word novel. This Milestone launches the final push toward the story���s conclusion. It���s the last place to add new information, characters, or clues. Everything the hero needs to know, to work with or to work alongside, must be in play by the end of the Second Plot Point. Otherwise, deus ex machina. But the protagonist���and reader���may not fully understand yet.

ACT 3 Part IV: The Resolution:The protagonist summons the courage and growth to come up with a solution, overcome inner obstacles, and conquer the antagonist. They���re empowered, determined. Heroic.

Climax

The hero conquers the antagonist or dies a martyr. Most will say the hero should never die at the end, but it is an option. And here���s when it���ll happen. In most novels the hero survives. It���s important to note the protagonist should be the one to thwart the antagonist, or at least lead the charge if it���s a group effort. They cannot be an innocent bystander.

Denouement

Denouement means unknotting in French, and that���s exactly what this Milestone accomplishes.After enduring the quest, stronger for the effort, the protagonist unravels the complexities of the plot, and begins their new life.

Quick note to ease the minds of pantsersI would never ask you to change your writing process or suggest planning trumps pantsing. There���s no right or wrong way to write a first draft. Whatever works best for you is the right way���for you. But once you have that first draft, read through from beginning to end and take note of the Acts, Parts, and Milestones. Your story sensibilities might be spot on and nothing needs to change. Great! But if your story feels ���off��� and you can���t figure out why, it���s most often because the Milestones aren���t in the correct order, or they arrive too late, or not at all. Add, subtract, or shuffle your scenes. Rebuild the skeleton of your story bone by bone.

The post The Skeleton of Your Story appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 8, 2022

Writer���s Fight Club Story Contest Winners!

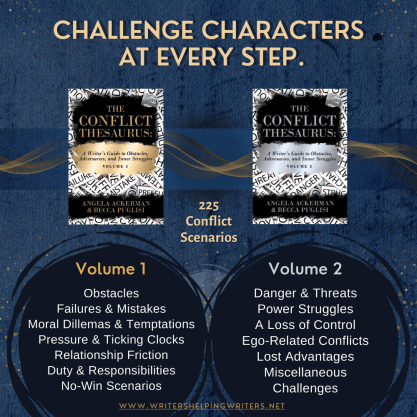

Thank you for celebrating the release of the SILVER Edition of The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer���s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles. Angela and Becca create amazing books���and find fun, generous ways to celebrate.

The Writer���s Fight Club Story Contest has been incredible. We enjoyed your entries and hope they���ll be published one day! Thank you for sharing your creativity, talent���and amazing conflicts.

Two of our Resident Writing Coaches donated edit prizes and judged the second round entries. I can���t wait for the talented winners to see their prizes below! If you didn���t win and are looking for an editor���check these coaches out to see if they���re a good match for you (you can see full bios for all our amazing Resident Writing Coaches here.)

Thanks Lisa Poisso and Colleen M. Story!Lisa Poisso��specializes in working with new and emerging fiction authors. Via her innovative Plot Accelerator and Story Incubator coaching, she fast-tracks authors through story theory and development while facilitating an author-paced ���developmental edit in a bottle.��� She holds a journalism degree and has decades of professional experience as an award-winning magazine editor and journalist, content writer, and corporate communications manager. In addition to story coaching, she is a developmental and line editor. Her popular Baker���s Dozen newsletter serves up 13 tasty tidbits for writers on a regular basis. Connect with an editor or coach who really gets your work with the��Writer���s Guide to Finding & Hiring an Editor. Find Lisa at LisaPoisso.com, download her free Manuscript Prep guide, and interact with her on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Colleen M. Story is a novelist, freelance writer, writing coach, and speaker with over 20 years in the creative writing industry. Her latest novel, The Beached Ones, released from CamCat Books on July 26, 2022. Her novel, Loreena���s Gift, was a Foreword Reviews��� INDIES Book of the Year Awards winner. Colleen has written three award-winning books to help writers succeed. Your Writing Matters, Writer Get Noticed! and Overwhelmed Writer Rescue. Check out free chapters! Colleen frequently serves as a workshop leader and motivational speaker, where she helps attendees remove mental and emotional blocks and tap into their unique creative powers. Find her at Writing and Wellness, Author Website, Life and Everything After, YouTube, Twitter, LinkedIn, Goodreads, BookBub and Instagram.

The Writers Helping Writers Street Team has helped us in so many ways, and we���re incredibly grateful. Here���s a huge thank you to the writers who judged the first round of our contest. Your thoughtful insight is greatly appreciated!

Thanks First Round JudgesStuart Wakefield

Jessica Subject

Shaley Nagle

Michelle Cornish

Randy Landenberger

Judy Kentrus

Faith Canright

Nicole Holloway

Megy Davis

Tracy Perkins

Rona Gofstein

Jan Sikes

Brandi MacCurdy

Kathy Swailes

Halli Gomez

Erica Converso

Julie Mcgue

Soquel Baumgardner

First Place: Diane Lee Sammet – Friend or Foe

First Place: Diane Lee Sammet – Friend or FoeConflict: Getting Caught in a Lie

Judge praise:

* I could feel the savviness of the author���s craft and the internal struggle of giving into fear & weight of guilt was really well done.

* I love this story! The conflict was so relatable.

* I want to know what happened next.

Prizes:

A $100 US cash prize

Two 1-year subscriptions to One Stop for Writers (One for you, one for a friend – $210 value)

A $100 US donation to your choice of charity that helps those impacted by conflict

A professional edit of your submission by our amazing Resident Writing Coach, Lisa Poisso

+ Bragging rights!

Conflict: Being Trapped

Judge praise:

* Boom���this scene sucked me right into the story.

*This grabbed me from the beginning ��� such a strong conflict!

* It held my attention from the beginning, and it was interesting and intriguing.

Prizes:

A $50 US cash prize

Two 6-month subscriptions to One Stop for Writers ��(One for you, one for a friend – $120 value)

A $50 US donation to your choice of charity that helps those impacted by conflict

A professional edit of your submission by our amazing Resident Writing Coach, Colleen M. Story

+ Bragging rights!

Conflict: Experiencing Discrimination

Judge praise:

* This made me feel something for the character, and I could imagine what it would have been like to find someone who completed you only to lose them, and the drudgery of settling for what was expected in life, not what the character wanted. And then of course, the second chance and taking the leap.

*I could feel the emotional conflict of discrimination in this story.

Prizes:

A professional edit of your submission by our amazing Resident Writing Coach, Lisa Poisso

+ Bragging rights!

I���m happy dancing for all the talented prize winners, and will e-mail you soon. Congrats to those who won prizes���and all the writers who prepared a submission and entered (which makes you winners in my eyes, too).

Pssst���speaking of prizes, everyone can get 25% off One Stop for Writers plans by using the one-time code SEVENYEARS until October 23.Thanks again for celebrating with Angela and Becca. Happy writing and revising!

The post Writer���s Fight Club Story Contest Winners! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 5, 2022

Themes and Symbols Go Together Like Peas and Carrots

So…symbolism. We���re pretty familiar with this storytelling element, and I���m guessing most of us have experimented with the use of symbols in our writing. In a nutshell, you take an object, word, color, phrase, etc., and apply it in a story to give it a deeper meaning:

Tolkien���s one ring (evil)

The floating feather (destiny/fate) in Forrest Gump

A Mockingjay (rebellion) in The Hunger Games

Some symbols are super obvious; other times, readers have more of a subconscious awareness that the object is really meant to represent X. Either way, when a symbol is deliberately included in a creative work, it���s almost always saying something about the story���s theme.

But theme ��� this one isn���t as easy to grasp. So let���s talk about this storytelling element and how you can use it along with symbolism to strengthen your writing.

What Is Theme?The theme of a story is the central message that explores a universal concept. Nature, good vs. evil, freedom���ideas like these are common to the human experience, and when we include them in our writing, readers tend to engage with them and connect with the text and the characters on a deeper level.

But thematic ideas themselves aren’t typically so neutral. The author will often bring their own worldview and perspective to bear on a given concept to form a thematic statement that supports a specific perspective:

We���re all part of the circle of life. (The Lion King)

Every human has equal capacity for good and evil. (Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde)

Freedom requires sacrifice. (Braveheart)

Typically, this statement emerges and is proven out through the protagonist���s journey. They may start out embracing the thematic statement, which is challenged along the way by other ideas, but it survives the test of time and holds true. (Or the protagonist refuses to embrace that statement, ensuring in most cases that the story ends in tragedy.)

Alternatively, the hero may come to the story with a contrasting statement that is eventually proven wrong. And in some cases, the protagonist has no particular dog in the thematic fight; they arrive on page one without an opinion either way about the main idea. But by the final pages, the people they���ve encountered and trials they���ve faced have made them believers in the thematic statement.

As authors, we���re orchestrating this process. Sometimes it happens subconsciously, with our deeply rooted opinions organically making their way onto the pages as we write. But others take a more strategic approach to theme; they know what idea they���re trying to get across. It���s just a matter of figuring out the best way to do it.

Well, good news! We���ve got some tried-and-true methods for you to do just that.

Use the Whole Cast Via…Contrasting Thematic Statements. If you���ve done your character creation homework, you���ve assembled a cast that is diverse in experience, personality, and mindset. As a result, each player will see the thematic idea from their own perspective. Allow readers to explore the central idea through the lens of those different viewpoints.

For instance, greed is the concept being explored in the movie Wall Street, and the players involved all see it a little differently. Protagonist Bud is a clean slate, with no preconceived ideas about it. His mentor lives by the mantra ���Greed is Good,��� and he has the money and moral ambiguity to prove it. Bud’s father, a hardworking blue-collar family man, believes that strength of character and being able to look yourself in the eye are more important than being rich. Bud’s girlfriend doesn’t reference greed overtly, but her ability to be bought says volumes. These viewpoints all leave an impression on Bud, formulating his ideas and influencing his journey to finally understanding and embracing his truth about the theme of greed.

Surround your protagonist with characters whose thematic statements contrast with his own. As the story unfolds and conflicts arise, the characters will respond based on their preconceived ideas about the theme. This will allow you to convey the idea you���re wanting to get across.

Personality Traits. We���re largely defined by our values, and this comes through in the traits that define us. The same is true for our characters. Someone who is honorable will look at greed differently than someone who is materialistic, selfish, or even ambitious. Likewise for an idealist vs. a cynic. Personality will naturally impact your character���s opinions and values, so whatever theme you want to explore, give each character the negative and/or positive traits that will make their beliefs about it make sense.

Experiences. A character���s ideals will also be influenced by their experiences. Let���s take, for example, a theme of family. Someone who grew up in a tight-knit, got-your-back family may swear by the adage that blood is thicker than water. But a character who was abandoned by their parents and has had to cobble together their own support system may believe that family is what you make it. Being raised in a home defined by rigid rules, strict punishments, and condemnation could cause someone to feel that family is a prison that must be escaped. Each character���s history���the good and the bad���will contribute to their personal ideas about your story theme. Set them up to have their own ideas about the theme by giving them the backstories that will support those beliefs.

PRO TIP: Your characters’ traits, experiences, and personal biases will influence how they approach the story theme, so it’s important for you to know these driving factors in your cast members.

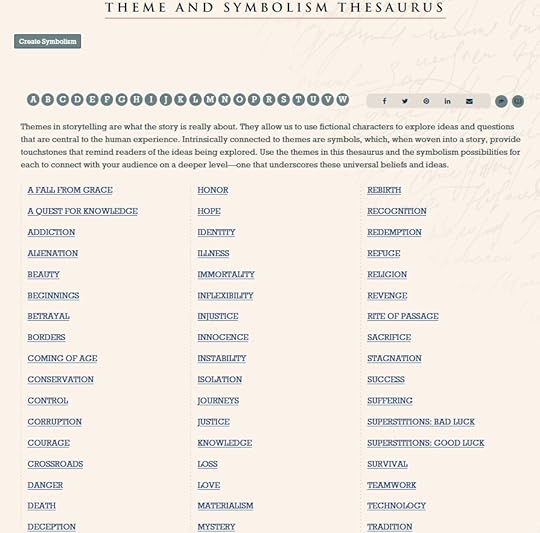

For this reason, we’ve structured the entries of One Stop for Writer���s Theme and Symbolism Thesaurus so you can explore these aspects for your characters and make smart decisions about their thematic statements. We’ve added 30 new entries to this collection and are in the process of updating the existing entries to include this helpful information, but you can see an example here.

Use Symbols to Reinforce Thematic Statements and Ideas

Use Symbols to Reinforce Thematic Statements and IdeasOnce you know the thematic statement you���d like to convey, an effective way to reinforce that idea is with some strategically chosen and placed symbols. Theme is abstract, but symbols turn it into something solid and concrete that readers can easily grasp. When it comes to finding the right symbols to reinforce your idea, keep the following options in mind.

Universal Symbols. While nothing is truly universal, certain objects are widely associated with certain themes, making them easier for readers to interpret. After all, they instinctively know that snakes symbolize evil, spring represents new beginnings, and a crown indicates royalty, so a universal symbol will make those references very clear.

However, because they���re used so often to stand for the same things, these objects can become a bit clich��d. If you���re worried about that and would like to go a more original direction, use something that���s unique to the character, instead.

Personal Symbols. These can be quite powerful because they relate directly to the character and their individual story. These objects can also contain inherent emotion because of the character���s connection to them.

Consider a woman who is defined by two things: she’s a competitive runner who has often been the victim of discrimination. A second-place marathon ribbon is in a prominent place in her study. It’s quite a prize, but to her, it doesn’t represent achievement or talent: it’s the moment success was stolen from her when she was sabotaged by another runner out of pure prejudice, a constant reminder of how important it is to keep fighting injustice and never giving up.

This unorthodox object as a symbol of injustice, discrimination, or possibly vengeance is original and makes perfect sense for this character. The strong emotional connection also stirs up a lot of emotion, which is always a good idea.

Symbols Within Symbols. If you���re looking for a fresh symbol, explore big devices for the gold nugget that may be hiding within. Weddings, for example, often represent a new beginning. But maybe the ceremony itself has been a little overdone in this context. To find something original that conveys the same meaning, go deeper into the wedding itself. The marriage certificate, a cake topper, the bride���s veil���even something as innocuous as the dried rose petals that were scattered by the flower girl on the big day can be used.

The little people, places, events, and objects associated with a bigger symbol can represent the same thing. Explore these micro options to come up with some unique symbolism choices to sprinkle throughout your story.

Symbols are potent, affecting how we feel about the chosen items. Themes are even more so because they get us thinking by challenging our ideas and deepest beliefs. Used together, your story���s theme and the symbols you use to reinforce it can create a deeper, more meaningful experience for readers.

For a list of themes, and the symbols representing each, visit our Theme and Symbolism Thesaurus Database at One Stop for Writers.

Birthday Bonus, Woot!

Birthday Bonus, Woot!One Stop for Writers is celebrating seven years this week with a 25% discount on all plans.

Whether you are an existing subscriber or you plan to become one to take advantage of all the powerful tools and resources there, grab this code and make your wallet happy. See you at One Stop!

The post Themes and Symbols Go Together Like Peas and Carrots appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 4, 2022

Happy 7th Birthday, One Stop for Writers!

It’s hard to believe another year has passed, but it’s birthday time again. One Stop for Writers is seven!

Over the years, Becca and I have stuffed this web app with innovative tools that help you think and write like story experts. And it’s been so great to see your confidence grow as you use them, and to know you’re getting more and more books into the hands of your readers. Thank you so much for letting us be part of your writing process!

Seven years is nothing to sneeze at, so here’s a sweet birthday discount for anyone who needs a war chest of storytelling tools to support them as they plan, write, and revise:

SEVENYEARS

To use this code: Sign up or sign in. Choose any paid subscription (1-month, 6-month, or 12-months) and add this code: SEVENYEARS to the coupon box.Add your payment details, and this one-time 25% discount will apply onscreen.Check the Terms box, and then hit the subscribe button.

To use this code: Sign up or sign in. Choose any paid subscription (1-month, 6-month, or 12-months) and add this code: SEVENYEARS to the coupon box.Add your payment details, and this one-time 25% discount will apply onscreen.Check the Terms box, and then hit the subscribe button. And that’s it! All of One Stop for Writers’ resources, including the incredible descriptive THESAURUS, is now part of your storyteller’s toolkit.

Code is active until October 23rd.

New to One Stop for Writers?If you’re not familiar with One Stop for Writers, join Becca for a virtual tour. She’ll show you exactly how this site is going to make writing stories much easier:

Planning your NaNoWriMo Novel?

One Stop for Writers is a powerful story planner, so if you’re gearing up for NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) now’s a great time to sign up for a free trial and start building your characters, plotting your story, and building your world. And once November hits, you’ll love having non-stop ideas on what to write, and how to find the right words, just a click away.

Thanks for helping us celebrate our birthday, and happy writing!

The post Happy 7th Birthday, One Stop for Writers! appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 1, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: Never Finding Happiness

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental health condition, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc. Please note that this isn’t a self-diagnosis tool. Fears are common in the real world, and while we may at times share similar tendencies as characters, the entry below is for fiction writing purposes only.

Fear of Never Being Happy

Fear of Never Being HappyNotes

A character who is afraid they will never be happy may feel unworthy of happiness. It’s also possible they’ve grown weary of life’s many disappointments and don’t want to get their hopes up any more. This fear creates a dichotomy of emotions, with the character either spending all their time chasing happiness or running from it.��

What It Looks Like

Searching for the one thing that will light the fire within them

Trying many different hobbies and pastimes

Researching philosophies, religions, and other ideologies

Spending a lot of time alone, soul-searching

Hopping from job to job trying to find the perfect one

Abusing drugs or alcohol, either as a way to find peace or numb the pain

Retreating or hiding from the world

Lashing out at others in frustration

Trying to be perfect

Engaging in negative self-talk

Struggling with making decisions

The character being unable to make a move toward something they desire��

Being unable to find things that excite them

Hating life and everything in it

Having a “why me” attitude

Common Internal Struggles

The character being unable to enjoy happy moments because they’re worrying about what could go wrong

Feeling numb even when something wonderful has happened��

Focusing on past hurts, even when things have gotten better

Worrying about the future instead of being grateful for the good things in the present

The character struggling with anxiety��

Being unable to see their own value��

Experiencing guilt or shame though they have done nothing wrong

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

Having a difficult time making friends

The character not going after what they want in life

Foregoing promising opportunities; settling for the status quo

Chronic substance abuse��

Being stymied by depression, social anxiety, etc.

Being paranoid that everyone is plotting against them

Believing that fate/God/the universe is working against them

Being driven by negative thoughts and emotions

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

Being victimized

Losing something that makes it seemingly impossible for the character to follow their passion (a musician going deaf, an athlete losing a limb, etc.)

The character being laid off from their perfect job

Experiencing a series of losses in a short span of time

A large-scale disaster (a weather event, economic depression, pandemic, etc.) negatively impacting the character

A health crisis that is difficult to overcome (cancer, a stroke, a chronic illness diagnosis, etc.)

The death of a loved one

A promising opportunity falling through at the last minute

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: Never Finding Happiness appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 29, 2022

Meet Our Resident Writing Coaches

I���ve had the pleasure of being the Writers Helping Writers Blog Wizard for a year���and have loved working with the Resident Writing Coaches. They���re all talented, generous authors who share their wisdom to help take your writing to the next level.

This is the 7th year of our popular Resident Writing Coach program where we feature writing experts through a series of four blog posts scattered throughout the year. We bring in a mix of expertise, so you benefit from different voices and perspectives from all over the world.

Each year we have some new coaches and some returning, so let me first say goodbye to the wonderful September C. Fawkes and Lisa Hall-Wilson. We greatly appreciate all you have shared with us.

I���m excited to introduce you to our wonderful new Resident Writing Coaches! Please give a warm welcome to���

Suzy Vadori is the award-winning author of The Fountain Series and is represented by Naomi Davis of Bookends Literary Agency. She is a certified Book Coach with Author Accelerator and the founder of the Wicked Good Fiction Bootcamp. Suzy breaks down concepts in writing into practical steps, so that writers with big dreams can get the story exploding in their minds onto their pages in a way that readers will LOVE.

In addition to her online courses, Suzy offers 1:1 Developmental Editing and Book Coaching services, and gives practical tips for writers at all stages on her vlog.

Find Suzy on her website, YouTube, Facebook, Free Inspired Writing Facebook Group, Instagram, and Twitter.

Michelle Barker is an award-winning author, editor, and writing teacher who lives in Vancouver, BC. Her newest novel My Long List of Impossible Things, came out in 2020 with Annick Press. It was a finalist for the Vine Awards and is a Junior Library Guild gold standard selection. She is the author of The House of One Thousand Eyes, which was named a Kirkus Best Book of the Year and won numerous awards including the Amy Mathers Teen Book Award. She���s also the author of the historical picture book, A Year of Borrowed Men, as well as the fantasy novel, The Beggar King, and a chapbook, Old Growth, Clear-Cut: Poems of Haida Gwaii. Her fiction, non-fiction and poetry have appeared in literary reviews around the world.

Michelle holds an MFA in creative writing from UBC and has been a senior editor at The Darling Axe since its inception, though she���s been editing and teaching creative writing for decades. She loves working closely with writers to hone their manuscripts and discuss the craft. You can find Michelle on Twitter, GoodReads, and Amazon.

In addition to our new coaches, we���re thrilled to have these returning masterminds���

Lucy V. Hay aka Bang2write is a script editor, author and blogger who helps writers. Lucy is the script editor and advisor on numerous UK features and shorts. She has also been a script reader for over 15 years, providing coverage for indie prodcos, investors, screen agencies, producers, directors and individual writers.

Publishing as LV Hay, Lucy���s debut crime novel, The Other Twin, is out now and is being adapted by Agatha Raisin producers Free@Last TV. Her second crime novel, Do No Harm, was a finalist in the 2019 Dead Good Book Readers��� Awards. Her next title is Never Have I Ever for Hodder Books. (Affiliate links)

Marissa Graff has been a freelance editor and reader for literary agent Sarah Davies at Greenhouse Literary Agency for over five years. In conjunction with Angelella Editorial, she offers developmental editing, author coaching, and more. She specializes in middle-grade and young-adult fiction but also works with adult fiction.

Marissa feels if she���s done her job well, a client should probably never need her help again because she���s given them a crash-course MFA via deep editorial support and/or coaching. Connect with Marissa on her Website, Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

Colleen M. Story is a novelist, freelance writer, writing coach, and speaker with over 20 years in the creative writing industry. Her latest novel, The Beached Ones, released from CamCat Books on July 26, 2022. Her previous novel, Loreena���s Gift, was a Foreword Reviews��� INDIES Book of the Year Awards winner, among others.

Colleen has written three books to help writers succeed. Your Writing Matters is the most recent, and was a bronze medal winner in the Reader Views Literary Awards (2022). Writer Get Noticed! was a gold-medal winner in the Reader���s Favorite Book Awards and a first-place winner in the Reader Views Literary Awards (2019). Overwhelmed Writer Rescue was named Book by Book Publicity���s Best Writing/Publishing Book in 2018. You can find free chapters of these books here.

Colleen frequently serves as a workshop leader and motivational speaker, where she helps attendees remove mental and emotional blocks and tap into their unique creative powers. Find her at Writing and Wellness, Author Website, Life and Everything After, YouTube, Twitter, LinkedIn, Goodreads, BookBub and Instagram.

Jami Gold, after muttering writing advice in tongues, decided to become a writer and put her talent for making up stuff to good use, such as by winning the 2015 National Readers��� Choice Award in Paranormal Romance for her novel Ironclad Devotion.

To help others reach their creative potential as well, she���s developed a massive collection of resources for writers. Explore her site to find worksheets���including the popular Romance Beat Sheet with 80,000+ downloads���workshops, and over 1000 posts on her blog about the craft, business, and life of writing. Her site has been named one of the 101 Best Websites for Writers by Writer���s Digest.

Find Jami at her website, Twitter, Facebook, Goodreads, BookBub, and Instagram.

Christina Delay is the hostess of Cruising Writers and an award-winning psychological suspense author. She also writes award-winning supernatural suspense for young adult and adult readers under the name Kris Faryn. Fun fact: Faryn means ���to wander or travel.��� Since that���s exactly what she loves to do, you���ll find juicy tidbits on exotic and interesting places in all her books!

Cruising Writers brings aspiring authors together with bestselling authors, an agent, an editor, and a world-renowned writing craft instructor together on writing retreats. Though on an extended vacation, you can sign up for news about upcoming retreats and fun travel tips here, follow Christina and Cruising Writers on Facebook, or find Kris on Facebook , Instagram, BookBub, and Amazon.

Lisa Poisso specializes in working with new and emerging fiction authors. A classically trained dancer, her approach to creativity is grounded in using structure, form, and technique as the doorway to freedom of movement. Via her innovative Plot Accelerator and Story Incubator coaching, she fast-tracks authors through story theory and development while facilitating an author-paced ���developmental edit in a bottle.���

She holds a journalism degree and has decades of professional experience as an award-winning magazine editor and journalist, content writer, and corporate communications manager. In addition to story coaching, she is a developmental and line editor, aided by an industrious team of retired greyhounds. Her popular Baker���s Dozen newsletter serves up 13 tasty tidbits for writers on a regular basis. Connect with an editor or coach who really gets your work with the Writer���s Guide to Finding & Hiring an Editor. Find Lisa at LisaPoisso.com, download her free Manuscript Prep guide, and interact with her on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Sue Coletta is an award-winning crime writer and an active member of Mystery Writers of America, Sisters in Crime, and International Thriller Writers. Feedspot and Expertido.org named her Murder Blog as ���Best 100 Crime Blogs on the Net��� (2018-2021). She���s also a member of the Kill Zone (Writer���s Digest ���101 Best Websites for Writers��� 2013-2021).

Sue lives with her husband in the Lakes Region of New Hampshire and writes psychological thrillers (Tirgearr Publishing) and true crime/narrative nonfiction (Rowman & Littlefield Group, Inc.). Sue teaches a virtual course about serial killers for EdAdvance in CT and a condensed version for her fellow Sisters in Crime. She���s appeared on the Emmy award-winning true crime series, Storm of Suspicion. In the fall she���s slated to appear on several episodes of Homicide: Hours to Kill. Learn more about Sue and her books at www.suecoletta.com.

Find Sue on her Website, Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, Goodreads, BookBub, Instagram, and YouTube.

TipsIf you want to browse past Resident Writing Coach posts, click here.

Check out all the Resident Writing Coach bios! You���ll find:

Editing and coaching servicesFree support through online groupsHelpful resourcesDon���t forget to follow them on social media for even more tips and updates!

Pssst���when you comment on their posts, they reply to you! So please share your thoughts and ask questions throughout the year. Angela, Becca and I love working with the coaches. They���re an incredible asset to the Writers Helping Writers blog.

Here���s to another year of amazing posts. Please welcome our Resident Writing Coaches. If there���s a topic you���d like help with, add it in the comments!

The post Meet Our Resident Writing Coaches appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 27, 2022

How to Reveal a Character’s Internal Conflict

If you’ve been on the writing trail long enough, you’ve heard plenty of talk surrounding conflict and the role it plays in storytelling. Whatever form it takes���annoying neighbors, quarrels with loved ones, car accidents, fistfights, ticking clocks���conflict keeps the story moving. It creates tension and complications while also providing opportunities for the character to grow and evolve as they navigate their character arc.

But some of the most compelling conflict doesn’t come from an external source. Rather, it lives within the character. These character vs. self struggles include a certain level of cognitive dissonance, with him wanting things that are at odds with each other. Competing wants and desires, moral quandaries, mental health battles, insecurity, confusion, self-doubt���internal struggles haunt the character because their impacts ripple outward, affecting not only how he sees himself but altering his future and often the lives of the people he cares about. They carry a heft that can���t easily be set aside.

Internal conflict is also critical for helping the character acknowledge the habits that are holding them back. Without that soul-cleansing tug-of-war, Aragorn would still be a ranger instead of the rightful king. Anakin Skywalker would have denied the goodness within, leaving Luke to die at the hands of the emperor. The Grinch would’ve stolen Christmas.

So it’s important to include this inner wrestling match for any character working a change arc. But equally important is how we reveal that struggle to readers. It’s all happening inside���meaning, we have to be subtle. The information has to be shared in an organic way through the natural context of the story. I’ve found the best method is to highlight the internal and external cues that hint at a character’s deeper problem.

Internal IndicatorsIf you’re writing in a viewpoint that allows you to reveal a character’s internal thoughts and processes, it’s a bit easier to draw attention to the struggle within. Just show the character experiencing some of the following:

Obsessive ThoughtsWhatever���s plaguing your character, she���s going to spend a lot of time thinking about it, because the only way to get past the insecurity is to figure out what to do and make a decision. So her thoughts should be circling the issue. You don���t want to spend too much time in her head, because too much introspection can slow the pace and diminish the reader���s interest. But the character should poke at the issue, examining it from different angles. Whatever���s going on in her life will bring her back to her inner conflict, and her thoughts should reflect that.

AvoidanceLike us, characters crave control and certainty, so not knowing what to do can make them feel incapable, afraid, and insecure. Being constantly reminded of their unsolvable problem might be emotionally painful enough for them to try to escape it. One way to convey this is by having them slam the door on a certain train of thought. Show their mind starting to wander in that direction and them deliberately turning away from it. Maybe they get really into work as a form of distraction. They may take avoidance a step further into full-blown denial, destroying paperwork or putting away mementos that remind them of the impossible decision so they can pretend it doesn���t exist. This is how you show that incongruency between what���s happening on the inside and the outside.

Wavering Between Courses of Action (Indecision)A dilemma is named such because the character doesn���t know what to do. It often takes a while for them to figure out what action to take, and the only way they can do that is to consider the options, so indecision is a major part of internal conflict. Show the character vacillating between choices, playing out various scenarios, weighing the pros and cons. This can be a great way to show the depth of the struggle.

External IndicatorsIf you’re limited in your ability to plumb the character’s depths���maybe because you’re writing in first person and can’t jump into the head of the love interest or villain���you can still show readers (and other cast members) that struggle. Just figure out the external signs of what’s happening inside, and show those.

Over or Under-CompensationThe character won���t be happy with their own inability to make a decision or take action. If their ego becomes involved or they���re the kind of person who wants to keep up pretenses, they may overcompensate by becoming forceful or pushy. Controlling external people and situations will make them feel better about their inability to control this other area of life.

Or your character could go a different direction. Plagued with indecision, they may become averse to making any choices at all. When even the smallest questions are raised, they defer to others. Letting other people take the lead ensures that the character won���t make a mistake, alleviating some of the pressure.

DistractionThe human brain can only focus on so many things at once. A character whose mind is consumed with a troubling scenario isn���t going to have much mental time for anything else. As a result, their efficiency and productivity at work or school could take a hit. They may become forgetful. Responsibilities they were always counted on to handle may be done halfway or fall completely to the wayside. These outer indicators will be a visible sign of the chaos beneath the surface.

MistakesCharacters under extreme pressure don���t always make the best decisions. Their distractibility, combined with any insecurities they may be feeling, can lead to mistakes that get them into trouble. For a character who is usually level-headed and logical, this can be like a neon sign to others that something isn���t right.

Emotional VolatilityWe all know what it���s like to be consumed by a problem we can���t fix. It steals our peace, our sleep, and our joy. This is fine���even normal���for short periods of time, but when it goes on for too long, it starts to take its toll. One of the first things to go is emotional stability.

A character in this situation may lose their patience, snap at people, or lash out at others. A different character may constantly be on the verge of tears, overwhelmed to the point of every little thing being the last straw. They may experience wild mood swings, reacting to everyday circumstances in unexpected ways. Your character���s response will depend on a host of other factors, including their personality and normal emotional range. Figure out which kind of response makes the most sense and you���ll be consistent in your portrayal of them, even in the most pressing of situations.

This is how you reveal an inner struggle: by focusing on the underlying and visible results of that conflict. The most important thing here is for you to know your character so you can predict how they’ll respond. Then you can clearly show what you know to readers.

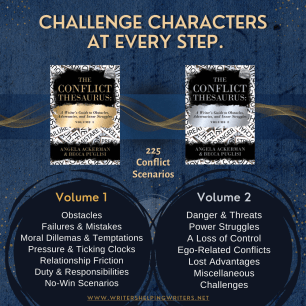

Want your conflict to go further?

Want your conflict to go further? The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer���s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles (Volume 1 & Volume 2) explores a whopping 225 conflict scenarios that force your character to navigate relationship issues, power struggles, lost advantages, dangers and threats, moral dilemmas, failures and mistakes, and much more.

You can also find the whole collection of entries in one place at One Stop for Writers.

The post How to Reveal a Character’s Internal Conflict appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 24, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: Becoming What One Hates

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental health condition, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc. Please note that this isn’t a self-diagnosis tool. Fears are common in the real world, and while we may at times share similar tendencies as characters, the entry below is for fiction writing purposes only.

Becoming What One Hates

Becoming What One HatesNotes

Some characters with this fear are worried about becoming someone dark and dangerous���a murderer, an abusive parent, or a psychopath. Others might worry about becoming the person they never thought they could or would be when they were young, from a mercenary capitalist to something more mundane, like a stay-at-home mom driving a minivan. This fear, taken to an extreme, could lead a character to not fully explore their own psyche, emotions, personality, and needs, giving them a skewed view of who they are and hindering the development of their true self.

What It Looks Like

Practicing asceticism or strict religious practices to prevent unwanted behaviors

Avoiding certain groups of people or situations where the undesired behavior may be triggered

Attending long-term therapy

The character seeking reassurance from others that they’re not taking on certain traits or attitudes

Going to extremes���e.g., someone who struggles with a forbidden sexual desire deciding to live a life of complete abstinence

Overcompensating

Voicing criticism of people who represent what the character fears

Becoming defensive if someone says something that suggests the character is similar to what they hate

Living a persona (pursuing hobbies, embracing opinions, etc.) that isn’t true to who they are

Avoiding interactions with the kind of people the character doesn’t want to emulate

Cutting people out of their life who represent what the character hates or who push them in that direction

Common Internal Struggles

Feeling guilty over secret desires to be “that person”

The character trying to accept facets of themselves while also staying true to their morals or principles

Struggling to avoid losing control of emotions or actions

Being drawn to the very people the character wants to distance themselves from

Feeling intense shame and self-loathing (for wanting to engage in certain activities, for being related to someone who exhibits something abhorrent, etc.)

The character wanting to be at peace with themselves but being unable to accept certain aspects of who they are

The character constantly searching themselves for signs that they’re becoming what they hate

The character doubting their instincts and motivations

Living in constant fear that someone will find out their deepest fears or desires

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

Coping with anxiety and depression

Not considering other sides of an issue, especially ones that oppose the character’s beliefs

Difficulty developing deep relationships with others because the character doesn’t believe they’re worthy or doesn’t trust themselves to make the right choices

Abusing drugs or alcohol to combat their fears or deal with perceived failures

Living a lie to fit in with others

Being unable to pursue things the character really wants because they’re associated with the thing they trying not to become

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

Having to associate with family members who embody what the character is trying to escape

Seeing media coverage of the type of person they are avoiding themselves

A situation that tempts the character to take a step toward what they’re trying to avoid

Feeling a compulsion to do the very thing that would turn the character into what they fear

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: Becoming What One Hates appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1022 followers