Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 44

December 15, 2022

How to Use Real Life to Inspire Your Fiction

The memoir section in any book shop is made of writers who have done outlandish, shocking or terrible things (or had them done to them). These books are popular because those writers are the exception, rather than the standard.

Whilst it���s said real life is ���stranger than fiction���, the reality is most of us have pretty straightforward lives. Some may even declare their own lives ���boring���.

So how can we use real life to inspire our fiction? It turns out there���s plenty of ways ��� Check these out for size.

Think: LocationAll of us have lived somewhere in our lives (perhaps many places!). This means we can utilize these locations to their best advantage in our fiction.

My latest novel, Kill for It, is set in Bristol, a city in the Southwest of England, UK. There were several reasons I chose Bristol ���

I know it very well. I���ve been visiting Bristol since I was a teen; my town is approximately forty-five minutes by train away. My adult son also lives there now. That means I know Bristol ���like the back of my hand��� (as people in the UK say!).Bristol is known for its culture. As the fourteenth biggest city in the UK, Bristol is very busy and cosmopolitan. It is known for its universities and colleges as well as its vibrant music scene, art and media. It is also the home of Banksy, the reclusive and renowned street artist, film director and activist.Bristol was in the news when I was starting my book. As I started outlining Kill For It, Bristol hit the worldwide headlines. The statue of the infamous slave trader Edward Colston was finally toppled by BLM protestors. (The statue had been subject to condemnation and multiple petitions for decades before Bristol residents took matters into their own hands. The statue is now in a museum).The combination of these three things made me realize I could use Bristol in my novel. Early reviewers like the fact the novel is not set in London too for a change!

Think: JobsMost of us will have lots of work experience. This real-life experience may include (but is not limited to): full-time or part-time employment; white collar versus blue collar work; Saturday jobs as teenagers; volunteering at charitable organizations; internships or unpaid caring.

Having real life experience of a particular job can be a great way of adding authenticity to our fiction.

Kill For It is set in the world of investigative journalism. The story pits young and upcoming journalist Cat against veteran reporter Erin. Cat is tired of not getting ahead at work, so comes up with a sickening plan to (literally!) grab the headlines. The only one who can stop her is Erin, but in doing so she must put her own life at risk.

The book draws on my own experience as a junior reporter in the late 90s/00s. I wrote for a variety of publications and sites (though I didn���t kill anyone ��� promise!).

The 90s and early 00s was a weird time for journalism. It was the age of the ���dot com bubble��� as well as ���The Millennium Bug���. I was also one of the last people to train before the internet changed the face of news and content forever!

I���d always wanted to write a story set against such a backdrop, so it was a real pleasure to write.

There���s one note of caution, however: DON���T imagine everything in a job stays the same decade to decade, or even year to year! If you have not done the job for a long time, you will still need to do some research to ensure your information is up-to-date.

Think: FavoritesThinking about what you enjoy reading or watching yourself in real life can really help you ���zero in��� on what you want to write in your own fiction.

Kill For It was inspired in part by Killing Eve, which I really enjoyed. I was lucky enough to interview Luke Jennings, author of the Killing Eve novellas, for LondonSWF365 in 2020.

He told me and the LSFers all about his work on the books and helping Phoebe Waller-Bridge with s1 of the acclaimed BBC TV series.

As an admirer of the psychopathic Villanelle, this lit the touchpaper in my imagination ��� so I was delighted when a beta reader proclaimed my antagonist Cat was ���Villanelle���s twisted little sister���!

In addition, one of my favorite movies is Dan Gilroy���s Nightcrawler (2014). In the film, Jake Gyllenhaal plays another psychopath: Louis Bloom, a con man desperate for work. He manages to muscle his way into the world of LA crime journalism where he blurs the line between reality on the stories he is reporting on.

Whilst Cat���s journey is different, the seed of the story is similar. In attempting to smash the glass ceiling, Cat will plumb depths no decent human should ever go to.

Think: PersonalAs writers, we all have personal experiences and opinions. We may even have started writing BECAUSE we feel the need to talk about such things.

One reason I write crime fiction is because Agatha Christie ��� the bestselling author of all time! – is a real ���shero��� of mine. Even better, she even comes from Devon, where I live too.

When I was growing up in the 80s and 90s however, movies, TV shows and books most often featured male protagonists. This annoyed me as a young girl and I remember thinking I would write female protagonists if I became a professional writer.

In addition, I was a teenage mother. Because of this, I discovered very quickly that the notion ���women can have it all��� ��� motherhood AND a career ��� was a lie. Even though I had great grades and a university degree, because I had a baby first it was extremely difficult to even get a job.

So, as a mother for over half my life now, I know how hard it is for women to juggle work and their responsibilities ��� Even when we manage it, it���s frequently held against us. After all, men STILL don���t get asked about their families or caring commitments like we do! I wanted to draw on this personal experience in KILL FOR IT.

That said, men are not the enemy in the book. KILL FOR IT takes aim at the system, not men. Whilst there���s at least one male character who is THE ABSOLUTE WORST, the point is not that men *as a whole* suck. Even female characters who don���t try and smash the system will lose their conscience and their humanity.

Of course, you may not have very strong feelings and opinions about a specific issue like I have. Other personal things you could mine for inspiration could include (but are not limited to):

FearsMost of us have fears, or even outright phobias. They may relate to specific childhood traumas or anxieties, or they may be difficult to understand. These fears may be universal, or they may be very niche.

Secrets��Secrets can be potent in storytelling. Most of us have them, so thinking about them can help us inform characters��� motivations in particular.

Moments you wish you could changeRegrets are common, especially if we did not act like our best self. However, even just wishing something unavoidable hadn���t happened can be good inspiration for our stories.

Favorite memories��And to the other end of the scale ��� just as we might wish things could have been different, there will be perfect moments in our lives that can act as story fuel, too.

Summing UpSo, don���t worry if your own real-life experiences are straightforward or even ���boring���. Chances are, you have plenty of lived experience you can use in your fiction to give it added authenticity and bite. Good luck!

The post How to Use Real Life to Inspire Your Fiction appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

December 13, 2022

���No, Don���t Tell Me���: How & When Should We Use Foreshadowing?

Foreshadowing is a literary technique we can use in our stories that gives a preview or hint of events that will happen later. While many might think of foreshadowing for mysteries, this literary device can be used in any genre.

In fact,��most��stories��need��foreshadowing of some type to keep readers interested��in what���s going to happen. That said, foreshadowing requires a��balance. When used poorly, foreshadowing can make our story feel boring or predictable, but when foreshadowing is used well, readers will find our story��more��satisfying.

How Can Foreshadowing Make Stories More Satisfying?While most aspects of writing contribute to readers��� sense of whether our writing is ���strong,��� foreshadowing helps create readers��� sense of whether we and/or our story have a plan, whether we���re going to take them on a worthwhile journey. In other words, foreshadowing can help create the sense that every element of the story has a purpose, that it���s all leading to a purposeful destination.

Hints of future story elements���even ones that just register with readers subconsciously���make story events fit into a sense of a bigger picture. While unexpected twists can make a story fun and avoid the feeling of being too predictable, foreshadowing can help a story hit the sweet spot of feeling inevitable-yet-surprising.

For example, imagine a final dilemma where a character faces a choice between two options illustrating the tug-of-war between aspects of their personality. If the story concludes with an unexpected twist as the character lands on a third option, the ending could feel like a cheat or an out-of-character decision ��� or it could feel like a brilliant way to resolve the story.

The difference between those reactions often comes down to whether the third option was foreshadowed at all, even in the most subtle, subconscious-registering way. A subtle foreshadowing can ensure that twist doesn���t feel like a cheat or out of character, and instead make it feel like the resolution was the point of the journey, adding to the sense of strong���and satisfying���storytelling.

Types of Foreshadowing

That said, before we can use foreshadowing effectively and find the right balance between leading readers along the storytelling journey and ���spoiling��� events, we need to understand more about foreshadowing as a writing technique. Different types of foreshadowing will fit our story at different times.

Some foreshadowing is direct and tells readers where the story is going. Other foreshadowing is more about subtle hints that are so indirect as to often be recognized only in hindsight.

Examples of Direct Foreshadowingmention of a future eventshow characters worrying about what might happena character declares that something won���t be a problem, which often hints to readers that the character will be proven wrong latershow or allude to tension that readers figure will eventually have to snapa prophecy of what the future will bringIf we���re writing in normal past tense rather than the default literary past tense, we can directly say what���s to come, such as: He didn���t know it yet, but that would be his last night at home.a flash-forward (often in a prologue or preface) showing events to comemention of emotions or thoughts of what a character longs for (even subconsciously), clueing readers into what their internal arc or internal goal will beDirect foreshadowing tells readers the what, but readers still read to learn the how.

Examples of Indirect Foreshadowingshow a lower-stakes version of the final conflict early, hinting at how the situation will play out latershow a prop or character skill in action earlier that will be important for the success of the final conflict (depending on how obvious the earlier incidence is, this type of pre-scene might be more direct than indirect)show a threatening object, hinting that it will eventually be used (i.e., Chekhov���s Gun) (depending on how obvious the appearance is���background vs. close up, etc.���we might consider this a direct technique rather than an indirect example)allude to something in a throwaway phrase, often burying the detail in the middle of a sentence and/or paragraph, letting readers skim over and forget about the hinttoss out a seemingly normal statement that will resonate with more meaning in future events lateruse similes or metaphors to hint at hidden traits or situationsshow a suspicious event, but have the viewpoint character believably decide there���s an innocuous reason, so readers don���t know the character assumed incorrectly until lateruse symbolism, such as how crows and ravens around a character often foreshadow their death or how weather often symbolizes a coming changeuse imagery and settings to create a certain mood appropriate to the later story, such as dread or creepinessIndirect foreshadowing uses subtlety, subtext, and/or misdirection to hide the story���s future, with the truth becoming clear only in hindsight.

3 Tips for How & When to Use ForeshadowingTip #1: Usually, Foreshadowing Should Be Avoided When���we���ve already foreshadowed the event, as we don���t want elements to feel repetitivethe event is unimportant, as the payoff won���t be worth the setup (exception: using it for non-anticipatory reasons, such as the setup and payoff of humorous details)we���ve already foreshadowed related events, as readers don���t want to know how everything will play outTip #2: Direct Foreshadowing Can Be Beneficial When It���establishes reader expectations, as meeting reader expectations makes our story more satisfyingmakes events seem credible, as by establishing the possibility, readers will be prepared to accept the eventsuses foreshadowed motivations to make characters seem more logical, as they���ll seem less like puppets to the plotincreases a story���s sense of foreboding, tension, or suspense, as readers might not know what exactly is going to happen, but they know it���s going to be badincreases a story���s sense of anticipation, as readers will want to know what happensmakes readers more invested, as they try to guess how the story will play outhelps us delay events until best for the story and reader anticipation, while still letting readers know that more interesting stuff is coming in the story soonmakes readers feel like they have a relationship with author-us, as readers interact with our writing to guess outcomesTip #3: Indirect Foreshadowing Can Be Beneficial When It���gives readers a sense of closure or gives our story the feeling of tying up loose endscreates a sense of the story being deliberately woven together with a surprising-yet-inevitable endingmakes readers feel more satisfied, like seeing the final piece of a puzzle fit and finally glimpsing the bigger pictureprovides a richer experience for readers by creating layers and parallelsavoids making the ending feel contrived or solved by waving a Deus Ex Machina wand, and instead makes events feel natural to the storygives readers the satisfying feeling of ���Wow! I can���t believe I didn���t see that coming��� rather than the angry or betrayed feeling of ���WTF? That came out of nowhere���increases emotions, such as making a tragedy more tragic by having the character (and reader) realize the tragedy could have been prevented if only they���d known earlier how X was significantprevents readers��� frustration when they���re purposely kept in the dark with lies, instead making them think they could have guessed with truths that are simply hidden.gives repeat readers something new to enjoy, as they put together new connections on a rereadUse Foreshadowing, but With PurposeWhether we���re using direct or indirect foreshadowing, the idea is to set up details, events, and concepts in our story that we later pay off with consequences, growth, change, etc.

Foreshadowing���setups and payoffs���creates echoes in our story that make our story feel more crafted, more purposeful, more deliberate, and more confident. All of that makes our story feel more meaningful to readers���and thus more satisfying. *smile*

Have you read stories with foreshadowing? Did the technique work for you (and why or why not)? Have you written stories with foreshadowing, or have you struggled to know how to use it (or find the right balance)? Can you think of other situations when foreshadowing would be beneficial or harmful? Do you have any questions about foreshadowing?

The post ���No, Don���t Tell Me���: How & When Should We Use Foreshadowing? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

December 10, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: Being Returned to an Abusive Environment

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental health condition, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc. Please note that this isn’t a self-diagnosis tool. Fears are common in the real world, and while we may at times share similar tendencies as characters, the entry below is for fiction writing purposes only.

Fear of Being Returned to an Abusive Environment

Fear of Being Returned to an Abusive EnvironmentNotes

A character who has escaped an abusive environment, whether as a child or an adult, and is determined to remain free will do anything to avoid going back to it. A fear of returning���voluntarily or against their will���to this place will trigger a host of physical, mental, and emotional reactions for the character, even if the event is unlikely to happen.

What It Looks Like

Becoming physically ill (nausea, headaches, stomachaches, hair loss, rashes, etc.)��

The character pleading their case to anyone who will listen

Threatening to harm themselves if they’re forced to go back

The character becoming desperately eager to please their current caregivers (to stay in their good graces)

Suffering from PTSD

Taking drugs or using alcohol to manage the fear��

Having nightmares about the environment or the abusive people there��

Pulling away from everyone

Becoming hypervigilant (watching for the abuser, whoever would bring news that the character has to go back, etc.)

Carrying a weapon

Becoming obsessed with self-defense

Creating an escape plan in case they’re forced to return

Hoarding money, travel supplies, and food so they can leave quickly if needed

Running away��

Common Internal Struggles

Having mixed feelings toward the abuser (especially if that person is a family member)

Trying and failing to stop thinking about abusive episodes

Wanting to fight the system that would return them to the abuser but feeling powerless to do so

Fantasizing about neutralizing the abuser

Feeling paranoid that the abuser or someone in his employ is watching the character

Feeling as if they will never be truly free

Struggling with suicidal thoughts

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

Avoiding romance to keep from falling into another abusive relationship

Becoming addicted to alcohol or drugs��

Insomnia impacting the character’s work or school performance

Being unable to trust the social systems or people who should protect the character

The character becoming homebound to avoid their abuser��

Having to move frequently to avoid the abuser or the people who would return the character to them

Difficulty building deep relationships with others because of an ongoing threat of being returned to the abuser (why bother making friends if you’re going to have to leave them?)

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

Being contacted by the abuser��

Suspecting that a friend is being abused

Watching a TV show or movie where someone is forced back into living with their abuser

Having to confront the abuser in court

Seeing the abuser in a social situation (at a family reunion, wedding, etc.)

Being told by loved ones or friends that the character is overreacting to the situation���that the abuse didn’t happen, they should give the abuser another chance, etc.

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

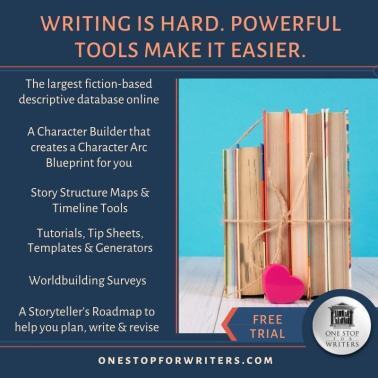

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: Being Returned to an Abusive Environment appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

December 7, 2022

A Gift for You: Secrets to Engaging Readers (Webinar Recording)

This time of year, we usually host a spectacular giveaway called Advent Calendar for Writers, and you may have noticed it’s missing this go-around.

I’ll be honest – life’s been hectic. Both my boys had weddings this October (so awesome!), but then a house move and my husband’s major surgery followed (he’s recovering well, thank goodness!). Needless to say, my mental tank is pretty low, so we made the call to skip Advent this year.

But are we skipping the gift-giving? Heck, no!

But are we skipping the gift-giving? Heck, no!If you’re interested in how to hack a reader’s brain using psychology and would like to know how a show-don’t-tell mindset steers you to opportunities to do more with your description, then this free webinar is for you!

Unfortunately because of some technical difficulties, it’s just me yammering away, but Becca’s there in spirit. We hope you find this dip into our process helpful, and that you walk away with ideas on how our thesauruses can help you write stronger characters and scenes. So, have a watch, and enjoy:

Psst! This is a limited time webinar, so make sure to view the recording before January 8th. Happy holidays!

The post A Gift for You: Secrets to Engaging Readers (Webinar Recording) appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

A Gift from Us: Secrets to Engaging Readers (Webinar Recording)

This time of year, we usually host a spectacular giveaway called Advent Calendar for Writers, and you may have noticed it’s missing this go-around.

I’ll be honest – life’s been hectic. Both my boys had weddings this October (so awesome!), but then a house move and my husband’s major surgery followed (he’s recovering well, thank goodness!). Needless to say, my mental tank is pretty low, so we made the call to skip Advent this year.

But are we skipping the gift-giving? Heck, no!

But are we skipping the gift-giving? Heck, no!If you’re interested in how to hack a reader’s brain using psychology and would like to know how a show-don’t-tell mindset steers you to opportunities to do more with your description, then this free webinar is for you!

Unfortunately because of some technical difficulties, it’s just me yammering away, but Becca’s there in spirit. We hope you find this dip into our process helpful, and that you walk away with ideas on how our thesauruses can help you write stronger characters and scenes. So, have a watch, and enjoy:

Psst! This is a limited time webinar, so make sure to view the recording before January 8th. Happy holidays!

The post A Gift from Us: Secrets to Engaging Readers (Webinar Recording) appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

A Gift from Us: Secrets to Engaging Readers (Webinar)

This time of year, we usually host a spectacular giveaway called Advent Calendar for Writers, and you may have noticed it’s missing this go-around.

I’ll be honest – life’s been hectic. Both my boys had weddings this October (so awesome!), but then a house move and my husband’s major surgery followed (he’s recovering well, thank goodness!). Needless to say, my mental tank is pretty low, so we made the call to skip Advent this year.

But are we skipping the gift-giving? Heck, no!

But are we skipping the gift-giving? Heck, no!If you’re interested in how to hack a reader’s brain using psychology and would like to know how a show-don’t-tell mindset steers you to opportunities to do more with your description, then this free webinar is for you!

Unfortunately because of some technical difficulties, it’s just me yammering away, but Becca’s there in spirit. We hope you find this dip into our process helpful, and that you walk away with ideas on how our thesauruses can help you write stronger characters and scenes. So, have a watch, and enjoy:

Psst! This is a limited time webinar, so make sure to view it before January 8th, and happy holidays!

The post A Gift from Us: Secrets to Engaging Readers (Webinar) appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

December 6, 2022

3 Action-Reaction Misfires That Flatten Your Writing

Cause and effect. Stimulus and response. Action and reaction. Everything in a story depends on what the characters do about whatever the story pushes them up against.

Stiff, disconnected, or missing character reactions snap the chain of cause and effect that constitutes your story. When readers can no longer see how and why the characters are doing what they���re doing, they lose the thread.

Let���s talk about the three most common action ���reaction misfires I see in manuscripts.

1. Missing or insufficient reactions

2. Jumbled responses

3. Purposely obscured stimuli

When characters fail to react to what���s happening around them, it’s as if nothing is happening at all. A snappy line of dialogue goes nowhere if it doesn���t get under someone���s skin. The first glimpse of a long-sought clue builds no excitement if nobody notices it. A punch in the nose might as well not have landed if it doesn���t start or end a disagreement.

When characters don���t react to the conversations and events around them, readers will assume they don���t care. If the characters don’t care, why should readers?

Keeping your characters engaged in the story keeps readers engaged with it too. When writing viewpoint characters, you have access to both internal and external responses. For other characters, you���re limited to whatever visible manifestations of those responses that the viewpoint character or narrator can perceive.

Internal ResponsesAll but the last type of internal response, thought, are involuntary reactions.

1. Involuntary sensations���These include physical sensations such as feeling a lump in the throat or a stomach full of butterflies.

2. Reflex reactions���These are the so-called knee-jerk reactions, such as jerking away from the source of pain.

3. Emotions���Before you can reveal emotions using any of these reaction modes, you as the writer must know what the emotion or blend of emotions actually is.

4. Thoughts���What���s the uncensored commentary running in the privacy of the character���s mind?

External ResponsesThese responses are conscious, voluntary reactions.

1. Voluntary action���These range from small-scale gestures (fist-pumping with glee) to story-moving choices (drawing a sword and attacking the duke).

2. Dialogue������We���ve never done it that way before���I don���t think it works like that,��� or ���I think I���m falling in love with you.���

Pro tip: Calibrate the number and scope of the responses to the significance of the stimulus. Dropping your keys on the floor merits a much smaller reaction than dropping your phone overboard into the sea. The more significant the stimulus, the more responses you can layer in. Tune with care. Over- or undercalibration makes the writing seem either melodramatic or flat.

Jumbled Responses

Almost as confusing to readers as a character who fails to react is a jumbled reaction that pulls the logical order of stimulus���response out of whack.

He scrabbled away from the roiling heap in which he���d landed. ���Get them off, get them off!���

It was ants���enraged, mandible-clacking ants, streaming over every inch of exposed skin. His whole frame jerked spasmodically, and a lacy net of agony cinched around his legs.

In this example, the hapless adventurer reacts by leaping away and shouting before readers even know there���s a problem. The narrator must loop back to explain (It was ants) and fill in the details. That���s not a dramatization of what���s happening (showing); it���s an explanation after the fact (telling).

Stimulus and response follows a predictable physiological pattern of perception and reaction. As a general rule of thumb, involuntary reactions come first. Next comes thought, as the character processes what���s happening. Finally, the character voluntarily and consciously reacts through action and dialogue.

STIMULUS���Our ill-fated adventurer tumbles into an ant hill.

1. INTERNAL RESPONSE���Sensation (involuntary): A lacy net of agony cinched around his legs.

2. INTERNAL RESPONSE���Reflex (involuntary): His whole frame jerked spasmodically ���

3. INTERNAL RESPONSE���Thought (voluntary): It was ants���enraged, mandible-clacking ants, streaming over every inch of exposed skin.

4. INTERNAL RESPONSE���Emotion (involuntary): Panic. You have a small window of creative leeway here. You could position this involuntary emotion after the voluntary thought in which he concludes that he���s covered in ants, or you could show him panicked by the sheer onslaught of physical reactions.

5. EXTERNAL RESPONSE���Action (voluntary): He scrabbled away from the roiling heap in which he���d landed. The order of these last voluntary actions is your call; your hero might shout first, then scrabble.

6. EXTERNAL RESPONSE���Dialogue (voluntary): ���Get them off, get them off!���

Poor guy.

Here���s how the passage would read if the scene were written following a physiologically logical order of reactions. You may give him an extra voluntary action (He peered down) in reaction to the pain, which allows him to reach the conclusion that inspires his next move.

A lacy net of agony cinched around his leg, and his whole frame jerked spasmodically. He peered down: Ants. Enraged, mandible-clacking ants, streaming over every inch of exposed skin.

He scrabbled away from the roiling heap in which he���d landed. ���Get them off, get them off!���

Purposely Obscured StimuliWhen you���re straining to create suspense, it���s easy to fall into withholding information���what I call Mysterioso Syndrome, the refusal to show readers what the characters are already clearly reacting to. This heavy-handed technique attempts to build dramatic tension by hiding or failing to identify the stimulus.

Let���s go back to the original, jumbled account of our hero���s tumble into the ant hill.

He scrabbled away from the roiling heap in which he���d landed. ���Get them off, get them off!���

It was ants���enraged, mandible-clacking ants, streaming over every inch of exposed skin. His whole frame jerked spasmodically, and a lacy net of agony cinched around his legs.

If the first paragraph were the end of the chapter, this dash of confusion could add a zing of cliffhanger-ish suspense.

But in the middle of a scene, refusing to let readers see what���s making our adventurer scrabble and shout momentarily puts the story on hold. It forces readers to wait for you to finish your clever little wait-for-it moment and get out of the way so that they, too, can see whatever the character���s in such a twist about.

Take heed: Modern readers want to see the story for themselves, not be left idling in the margins while you parse out explanations one crumb at a time. Let readers into the story: Cause, then effect. Stimulus, then response. Action, then reaction.

The post 3 Action-Reaction Misfires That Flatten Your Writing appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

December 3, 2022

Fear Thesaurus Entry: Losing One’s Heritage or Cultural Identity

Debilitating fears are a problem for everyone, an unfortunate part of the human experience. Whether they’re a result of learned behavior as a child, are related to a mental health condition, or stem from a past wounding event, these fears influence a character’s behaviors, habits, beliefs, and personality traits. The compulsion to avoid what they fear will drive characters away from certain people, events, and situations and hold them back in life.

In your story, this primary fear (or group of fears) will constantly challenge the goal the character is pursuing, tempting them to retreat, settle, and give up on what they want most. Because this fear must be addressed for them to achieve success, balance, and fulfillment, it plays a pivotal part in both character arc and the overall story.

This thesaurus explores the various fears that might be plaguing your character. Use it to understand and utilize fears to fully develop your characters and steer them through their story arc. Please note that this isn’t a self-diagnosis tool. Fears are common in the real world, and while we may at times share similar tendencies as characters, the entry below is for fiction writing purposes only.

Fear of Losing One’s Heritage or Cultural Identity

Fear of Losing One’s Heritage or Cultural IdentityNotes

Cultural differences���ones we adopt or are born into���are part of what define us. For a character who understands this, losing that aspect of their identity can shake the foundation of who they are and threaten the deep connections they have with others from their culture. This is an enormous loss. While it’s normal and healthy to nurture one’s heritage for oneself and one’s family, a fear of losing that sense of identity���whether the possibility is real or perceived���can drive the character to great (even unhealthy) lengths to keep it from happening.

What It Looks Like

Holding firmly to personal traditions

Observing cultural rituals to keep them alive and relevant

The character educating their children about their culture: engaging in traditions, telling them stories about their heritage, speaking their native language at home, etc.

Seeking to educate others about the character’s culture���forming a club at school or a committee at work, for instance

Becoming an activist

The character seeing offense or slights against their culture where none were intended

Refusing to assimilate or integrate into a different culture

Living a life at home that looks different from the character’s life outside of the home

Only associating with people within the character’s cultural group

The character sheltering their children from influences outside of their community

The character unintentionally passing their fear of others to their children

Requiring loved ones to choose spouses from within their cultural group

Scorning those outside of the character’s community (rejecting them before they can reject the character)

Developing an��us vs. them��mentality

Common Internal Struggles

The character wanting to maintain their cultural identity but also wanting to fit in with others

Feeling conflicted about their identity

Being drawn to the practices of other cultures and feeling disloyal

Fearing certain people groups outside of the character’s community

The character constantly fearing that they’re losing their children to another culture

The character wanting to protect their children from being drawn away by other cultures but recognizing that doing so is damaging their relationship

Flaws That May Emerge

Abrasive, Confrontational, Cynical, Defensive, Haughty, Hostile, Impatient, Impulsive, Inhibited, Insecure, Judgmental, Martyr, Melodramatic, Oversensitive, Pessimistic, Resentful, Suspicious

Hindrances and Disruptions to the Character’s Life

Missing out on valuable experiences, learning opportunities, and advances from other cultures that could benefit the character

Experiencing discrimination or harassment for their beliefs

Strained relationships with family members who want to integrate with the rest of the world

Only feeling safe and understood within their own community

Always feeling like an outsider

Becoming judgmental or prejudicial about people from other cultures

Scenarios That Might Awaken This Fear

A natural disaster or human conflict destroying a sacred site

Seeing other people’s children abandon their heritage

A child choosing to date someone from outside of the family’s culture

Witnessing the passage of laws that target their culture or heritage (prohibiting certain headwear, a form of worship being forbidden, etc.)

Being targeted because of the character’s heritage

Being pressured to fit in

A “bad apple” who shares the character’s culture committing a crime or gaining notoriety, generating animosity from the public

Other Fear Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (16 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, and then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Fear Thesaurus Entry: Losing One’s Heritage or Cultural Identity appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

November 30, 2022

Writing Antagonists Readers Can���t Help But Like

There’s a dirty little secret among many of us readers: well-written antagonists get our blood pumping. When a scene come along with them in it, well, we lean closer. Grin a little more. Not because we’re a bunch of budding psychopaths and this is some alter-ego role play–okay, maybe a little–no, it’s that deep down, there’s something we like about them. Maybe even admire.

What now? you say. How is that possible? He (or she) is the baddie, after all!

Indeed. And we know it. But just like a protagonist, the antagonist can have something special about them too. It’s not a hollow quirk, catch-phrase, or great sense of style that draws us in. No, it’s something deeper, something attached to their identity or life experience. We see this part of them and relate to it because it reminds us of something we’ve seen or experienced in our own real-world journey.

Is relatability only for protagonists?A lot of airtime is devoted to building a relatable protagonist because it makes the character accessible to readers in a meaningful way. Relatability is a rope that ties the two together – in some significant way, readers see the hero or heroine is like them. Maybe they’ve both felt the same thing, been in the same situation, experienced the same heartache or sting of failure. This common ground helps a bond of understanding and empathy to form, and the reader becomes invested in what happens to the character. They root for the protagonist and care what happens to them.

We don’t see as much written on the subject of relatability when it comes to the antagonist or villain because writers are supposed to nudge the reader into the protagonist’s camp, not the antagonist’s. Unfortunately, though, this can send the wrong message about the importance of our darker characters, leading to some writers glossing over their development so they end up with clich��, yawn-worthy villains.

Antagonists should be as developed as protagonists.

They should have understandable motivations (for them), have a history that shows what led them down the dark alley of life, and an identity, personality, and qualities that make them a tough adversary for the protagonist to beat. The more dedicated, skilled, and motivated the antagonist is, the more of a challenge they will be, leading to great friction, tension, clashes, and conflict.

So, just as we want to show readers a protagonist’s inner layers and give them ways to connect and care about the protagonist, we should encourage readers to find something good or relatable about the antagonist so it causes the reader to be conflicted. They may not agree with the antagonists’ goal or how they go about getting it, but maybe they understand why this story baddie wants what they want, or they admire certain qualities they have.

When readers are torn over how to feel, they become more invested in the story.Life is not always black and white, is it? So it’s okay if a tug of war goes on inside them over who is right and who is wrong in the story, or if they care enough about the villain to hope they will choose to turn from their dark path, and redemption may be possible.

So how do we make an antagonist relatable?

Common human experiences, especially ones that encourage moral confliction, are a great way to show readers they have something in common with the antagonist. For example, consider temptation.

Haven’t you ever been tempted to cross a moral line?

Did you ever want to make someone pay because they deserved it?

Have you ever ignored society’s rules because they don’t make sense, are unfair, or were built to benefit a select few?

Temptation is something we’ve all felt, and wrestle with. Sometimes we remain steadfast, other times we give in. So having a darker character be tempted in a way readers relate to will cause them to identify with the antagonist’s mindset.

Another way to use temptation is to get readers to imagine the what if, which can be another area of common ground:

What if you could easily let go of guilt and do what feels right for you? What if you could break the law for the right reasons and serve a greater good? What if you could go back in time and erase someone who really deserves to be erased?This can work well if you tie the antagonist’s desire to embrace the dark side because of a past trauma. For example…

Maybe they do whatever feels right because they were enslaved by a cruel master as a childThey break the law because those who make them are corrupt and entitledThey go back and erase someone because that person killed their beloved and unborn childCan’t we all relate to these dark motivations just a little? Don’t they help us understand where the character’s behavior is coming from? We may not morally agree with what the antagonist does, but we do feel some connection to them.

And I’m convinced this last one is the key because antagonists and villains have an Achilles heel: their role. As soon as it’s clear they are cast as the Bad Guy or Gal, readers put them in a box. They must be a jerk, a sore loser, a narcissist, someone who’s all about power and control. They must be unlikable.

And I don’t know about you, but when the antagonist or villain turns out to be exactly those things, I’m disappointed. Why? Because it’s expected: good guy faces off against typical bad guy, good guy wins. Yawn.

Relatability makes it okay to like the antagonist, even though they do bad things.So, to recap and offer a few more ideas…

Craft a backstory that���s as well-drawn as the Protagonist’s. As the author, you need to know why they’re messed up and take the dark path. Use a past tragedy to help readers understand what led them to their role. Maybe you can even reveal this in a way that causes readers to wonder if they would be any different had they been in the antagonist’s shoes.

Give them a credible, understandable motivation. Even if their goal is a destructive one, they should have a good reason for wanting it. (For ideas on what this could look like, check out the Dark Motivations in this database.)

Give them a talent, something helpful or interesting. Just like a protagonist, your antagonist likely is skilled in some way. What talent or skill will help them achieve their goal? And you can always make this an interesting dichotomy, like an antagonist with a talent for healing who takes in hurt animals but lacks the same empathy for humans.

Give them a quality or trait that is undeniably admirable. It’s easy to paint a villain as being all bad, so skip the clich�� and give them a belief they live by. Maybe they keep every promise or hold honestly in the highest regard and so are always truthful, even if it makes them look bad. Of course, the dark side might be that they don���t suffer lies of any kind, and punish them severely.

Make them human. Sometimes writers can go on a “power and glory” tear and forget their antagonist is as prone to ���Average Joe��� problems as anyone else. Does their roof leak, do they have visitors show up at an inconvenient time, do they get sick?

Antagonists can have a hobby or secret, struggle over what to do, or regret words said in haste just like the rest of us. So while you highlight their dark ways and volatile emotions, remember to also show how in some ways, they’re just like anyone else.

The post Writing Antagonists Readers Can���t Help But Like appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writing Antagonists that Readers Can���t Help But Like

There’s a dirty little secret among many of us readers: well-written antagonists get our blood pumping. When a scene come along with them in it, well, we lean closer. Grin a little more. Not because we’re a bunch of budding psychopaths and this is some alter-ego role play–okay, maybe a little–no, it’s that deep down, there’s something we like about them. Maybe even admire.

What now? you say. How is that possible? He (or she) is the baddie, after all!

Indeed. And we know it. But just like a protagonist, the antagonist can have something special about them too. It’s not a hollow quirk, catch-phrase, or great sense of style that draws us in. No, it’s something deeper, something attached to their identity or life experience. We see this part of them and relate to it because it reminds us of something we’ve seen or experienced in our own real-world journey.

Is relatability only for protagonists?A lot of airtime is devoted to building a relatable protagonist because it makes the character accessible to readers in a meaningful way. Relatability is a rope that ties the two together – in some significant way, readers see the hero or heroine is like them. Maybe they’ve both felt the same thing, been in the same situation, experienced the same heartache or sting of failure. This common ground helps a bond of understanding and empathy to form, and the reader becomes invested in what happens to the character. They root for the protagonist and care what happens to them.

We don’t see as much written on the subject of relatability when it comes to the antagonist or villain because writers are supposed to nudge the reader into the protagonist’s camp, not the antagonist’s. Unfortunately, though, this can send the wrong message about the importance of our darker characters, leading to some writers glossing over their development so they end up with clich��, yawn-worthy villains.

Antagonists should be as developed as protagonists.

They should have understandable motivations (for them), have a history that shows what led them down the dark alley of life, and an identity, personality, and qualities that make them a tough adversary for the protagonist to beat. The more dedicated, skilled, and motivated the antagonist is, the more of a challenge they will be, leading to great friction, tension, clashes, and conflict.

So, just as we want to show readers a protagonist’s inner layers and give them ways to connect and care about the protagonist, we should encourage readers to find something good or relatable about the antagonist so it causes the reader to be conflicted. They may not agree with the antagonists’ goal or how they go about getting it, but maybe they understand why this story baddie wants what they want, or they admire certain qualities they have.

When readers are torn over how to feel, they become more invested in the story.Life is not always black and white, is it? So it’s okay if a tug of war goes on inside them over who is right and who is wrong in the story, or if they care enough about the villain to hope they will choose to turn from their dark path, and that redemption may be possible.

So how do we make an antagonist relatable?

Common human experiences, especially ones that encourage moral confliction, are a great way to show readers they have something in common with the antagonist. For example, consider temptation.

Haven’t you ever been tempted to cross a moral line?

Did you ever want to make someone pay because they truly deserve it?

Have you ever ignored society’s rules because they don’t make sense, seem fair, or were built to benefit a select few?

Temptation is something we’ve all felt, and wrestle with. Sometimes we remain steadfast, other times we give in. So having a darker character face a temptation that readers relate to will cause them to identify with the antagonist’s mindset because they’ve been there themselves.

Another way to use temptation is to get readers to imagine the what if, which can be another area of common ground:

What if you could just let go of guilt and do what feels right for you? What if you could break the law for the right reasons and serve a greater good? What if you could go back in time and erase someone who really deserves to be erased?This can work well if you tie the antagonist’s desire to embrace the dark side of morality because of a past trauma. For example…

Maybe they do whatever feels right because they were enslaved by a cruel master as a childThey break the law because those who make them are corrupt and entitledThey go back and erase someone because that person killed their beloved and unborn childCan’t we all relate to these dark motivations just a little bit? Don’t they help us understand where the character’s behavior is coming from? We may not morally agree with what the antagonist does, but we do feel some connection to them.

And I’m convinced this last one is the key because antagonists and villains have an Achilles heel: their role. As soon as it’s clear they are cast as the Bad Guy or Gal, readers put them in a box. They must be a jerk, a sore loser, a narcissist, someone who’s all about power and control. They must be unlikable.

And I don’t know about you, but when the antagonist or villain turns out to be exactly those things, I’m disappointed. Why? Because it’s expected: good guy faces off against typical bad guy, good guy wins. Yawn.

Relatability makes it okay to like the antagonist, even though they do bad things.So, to recap and offer a few more ideas…

Craft a backstory that���s as well-drawn as the Protagonist’s. As the author, you need to know why they’re messed up and take the dark path. Use a past tragedy to help readers understand what led them to their role. Maybe you can even reveal this in a way that causes readers to wonder if they would be any different had they been in the antagonist’s shoes.��

Give them a credible, understandable motivation. Even if their goal is a destructive one, they should have a good reason for wanting it. (For ideas on what this could look like, check out the Dark Motivations in this database.)

Give them a talent, something helpful or interesting. Just like a protagonist, your antagonist likely is skilled in some way. What talent or skill will help them achieve their goal? And you can always make this an interesting dichotomy, like an antagonist with a talent for healing who takes in hurt animals but lacks the same empathy for humans.��

Give them a quality or trait that is undeniably admirable. It’s easy to paint a villain as being all bad, so skip the clich�� and give them a belief they live by. Maybe they keep every promise or hold honestly in the highest regard and so are always truthful, even if it makes them look bad. Of course, the dark side might be that they don���t suffer lies of any kind, and punish them severely.

Make them human. Sometimes writers can go on a “power and glory” tear and forget their antagonist is as prone to ���Average Joe��� problems as anyone else. Does their roof leak, do they have visitors show up at an inconvenient time, do they get sick?

Antagonists can have a hobby or secret, struggle over what to do, or regret something they said just like the rest of us. So while you highlight their dark ways and emotions, remember to show that in some regards, they are just like anyone else!

The post Writing Antagonists that Readers Can���t Help But Like appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1022 followers