Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 17

October 15, 2024

Three Ways You���re Losing Your Reader���s Trust (And How to Avoid Them)

There���s no better feeling than being in the hands of a great storyteller. They have command of the details we need to know, the scenes we need to see, and there���s a lock-step feel to the way the story advances. Strong storytelling isn���t just a unique premise or a character we love.

Strong storytelling is rooted in trust.

Trust in the person who has crafted the story, but also trust in the viewpoint character. If we feel as though the character shares with us everything they know and allows us to be along for all critical moments of their story, we can feel as though we are that character.

Let���s discuss three very simple ways you might be breaking your reader���s trust, intentionally or not. We���ll also cover what to do so your reader feels like those strong storytelling hands they���re in are yours.

Trust Violation #1: When we allow the character to react before we���ve shown the reader what they���re reacting to.Example: Holly stumbled backward. What she saw made her gasp. Could it be? There stood the man she thought was dead.

Notice how in the example, we have two lines of body language that point to surprise and shock, not to mention a third line where it���s clear she���s questioning whatever she���s seeing. All of these lines tell the reader how Holly (and how they) should feel before they even know what they���re seeing. On a small scale, this type of writing distances the reader from the character. The reader feels frustration for those three lines, waiting to see whatever it is that Holly���s seen. It backfires on Holly, the narrator, and even the writer because the reader starts to wonder why they aren���t being told what they need to know. In that span of time, they feel other���like they���re not Holly, which is what we don���t want at all. Instead, we want the reader to be in every moment with her, processing all her senses are processing in real time. That reinforces the feeling that the reader knows as much as she knows, and it shows the reader respect in leaving room for them to deduce how to feel when they first observe what the character does.

Bottom line: Present sensory-based action and observation first, and build in character reaction second.

Trust Violation #2: When we withhold a character���s name/identity just to perpetuate tension.

Example: Julie watched the figure make their way down the staircase. The way they moved was slow and sleek, commanding the attention of everyone below. Julie focused on the drink in her hand, determined not to let him control her the way he controlled everyone else. This was exactly why she left her ex-boyfriend in the first place.

In this example (somewhat like the first), we���re getting the character���s reaction before we���re entirely certain who or even really what they���re reacting to. To be fair, we do get movement and sensory-based action prior to Julie���s clear emotional reaction. But notice how for many lines, we have no idea who the ���figure��� is and Julie and the narrator do. Clearly, the space is well-lit based upon the details. Julie obviously knows who the figure is because she reacts in a specific way. And yet, we don���t get access to that same information in real time. A feeling creeps in from this type of withholding, and it���s something along the lines of being manipulated for the sake of drawing out the tension. The writer reveals themselves as the ���man behind the curtain��� and the writing draws attention to itself. When we use this type of writing, we aren���t keeping the figure���s identity unknown for a reason rooted in logic or plot. The figure isn���t wearing a disguise or hidden for some other reason. It���s evident Julie (and the writer) knows who he is. So why not just use their name? Why not tell us all that the character knows when she knows it? The answer is that there isn���t a reason, and readers will inherently know we���re pulling strings to tap into their curiosity.

Bottom line: Let us fully know all your viewpoint character knows the moment they know it. Avoid using tricks that withhold names or other information for the sake of making your reader curious because the reader will know they���re being manipulated.

Trust Violation #3: When we catch the reader up on what the character did since we last saw them.Example: Brian snuck through the front door, clenching the keys to his dad���s truck. Sometime overnight, Brian had come up with a plan. If Dad was going to insist that drinking and driving was perfectly fine, Brian would take charge of things.

There are absolutely times in storytelling when we want to compress time and leap over what happens in a character���s life. Sleeping, eating, traveling���These are often spots where nothing important and plot-bearing is happening, and we can bypass them altogether. But when the character has seemingly made a choice during a gap of time���a choice that relates to the pursuit of their goal���we should have access to it as it occurs. Plan-making should be born out of active scene. In other words, we should be in the scene whereby the threads of the new decision start to emerge, and we should even see hints of what the character might do next. Or, we should simply and fully know what they plan to do by the time we leave one scene and get ready for the next one. In the example above, unless Dad came home drunk the night before and we saw Brian eyeing Dad���s keys with a sense of hope rising in him���all clues that would logically allow us to predict what Brian might do next���then we feel like he���s made a decision without us. On his own and apart from us. And that separation causes us to not only lose trust in the character, but also the writer. As basic as it sounds, a feeling emerges like the character has been off doing important things without us, and we���re a bit bummed to have been left out. This type of writing makes your reader stop and ask, ���Wait, what?��� because the character���s decision has been made off-the-page without enough clues to feel logical or predictable.

One way you can tell when this sort of thing happens is that there hasn���t been time for the character (or the reader) to weigh the cost of the choice the character is ultimately going to make. We don���t know what Brian is knowingly losing in taking his dad���s truck, the risks specific to his character, or what���s at stake that he���s choosing to risk in pursuit of this goal. We don���t get the benefit of being with him as he makes the decision itself. There���s a feeling like it���s happening too fast and somewhat suddenly, and that makes us doubt Brian���the character we want to feel like represents us.

Bottom line: When your character makes a crucial decision toward their goal, make sure that it���s made (even partially via context clues) during active scene so that your reader feels like the character���s ally in every moment of the story.

What types of craft choices do you experience as a reader that break your trust? Do you struggle with these types of choices as a way of drawing out or generating tension? What other ways do you find help maintain that writer-character-reader trust?

Happy writing!Marissa

The post Three Ways You���re Losing Your Reader���s Trust (And How to Avoid Them) appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 12, 2024

Character Secret Thesaurus Entry: Having An Undisclosed Bias

What secret is your character keeping? Why are they safeguarding it? What’s at stake if it’s discovered? Does it need to come out at some point, or should it remain hidden?

This is some of the important information you need to know about your character’s secrets���and they will have secrets, because everyone does. They’re thorny little time bombs composed of fear, deceit, stress, and conflict that, when detonated, threaten to destroy everything the character holds dear.

So, of course, you should assemble them. And we can’t wait to help.

This thesaurus provides brainstorming fodder for a host of secrets that could plague your character. Use it to explore possible secrets, their underlying causes, how they might play into the overall story, and how to realistically write a character who is hiding them���all while establishing reader empathy and interest.

Maybe your character…

Has an Undisclosed BiasABOUT THIS SECRET: A character is biased when they view someone negatively and attribute flaws to that person without proof that those qualities apply. It might result from a negative encounter or traumatic experience with a specific individual, learned behavior from a trusted person, or repeated exposure to hurtful stereotypes (through the media, for example). In an environment where the bias isn���t widely accepted, the character will mask or hide it to avoid judgment, rejection, banishment, discrimination, or reputational fallout.

SPECIFIC FEARS THAT MAY DRIVE THE NEED FOR SECRECY: Being Taken Advantage of, Being Unsafe, Certain Kinds of People, Persecution, Putting Oneself out There, Trusting Others

HOW THIS SECRET COULD HOLD THE CHARACTER BACK

Causing friction with loved ones who don���t agree with the bias

Feeling guilt and shame over what their dark, biased thoughts say about who they are

Being deprived of an enriching or helpful relationship with someone from the biased group

Missing out on the opportunity to gain allies or share resources

The character���s perspective always being limited to align with people who think like them

BEHAVIORS OR HABITS THAT HELP HIDE THIS SECRET

The character entertaining the bias in their mind but not speaking it aloud

The character gravitating toward people who think like them

Justifying their reasons for not engaging with the people they���re biased against

Expressing support for those people but not offering them the same opportunities the character would offer to others

Mentally using labels for certain people but not verbally referring to them that way

ACTIVITIES OR TENDENCIES THAT MAY RAISE SUSPICIONS

Making jokes about the people they distrust

Passive-aggressiveness (backhanded compliments, talking about a member of this group behind their back, etc.)

Not questioning gossip and rumors that cast certain people in a negative light

Not requiring proof of wrongdoing to the same degree the character requires it from other people

Standoffish behavior around this group

SITUATIONS THAT MAKE KEEPING THIS SECRET A CHALLENGE��

Making jokes about the people they distrust

Passive-aggressiveness (backhanded compliments, talking about a member of this group behind their back, etc.)

Not questioning gossip and rumors that cast certain people in a negative light

Not requiring proof of wrongdoing to the same degree the character requires it from other people

Standoffish behavior around this group

Other Secret Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Secret Thesaurus Entry: Having An Undisclosed Bias appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Character Secret Thesaurus Entry: An Undisclosed Bias

What secret is your character keeping? Why are they safeguarding it? What’s at stake if it’s discovered? Does it need to come out at some point, or should it remain hidden?

This is some of the important information you need to know about your character’s secrets���and they will have secrets, because everyone does. They’re thorny little time bombs composed of fear, deceit, stress, and conflict that, when detonated, threaten to destroy everything the character holds dear.

So, of course, you should assemble them. And we can’t wait to help.

This thesaurus provides brainstorming fodder for a host of secrets that could plague your character. Use it to explore possible secrets, their underlying causes, how they might play into the overall story, and how to realistically write a character who is hiding them���all while establishing reader empathy and interest.

Maybe your character…

Has an Undisclosed BiasABOUT THIS SECRET: A character is biased when they view someone negatively and attribute flaws to that person without proof that those qualities apply. It might result from a negative encounter or traumatic experience with a specific individual, learned behavior from a trusted person, or repeated exposure to hurtful stereotypes (through the media, for example). In an environment where the bias isn���t widely accepted, the character will mask or hide it to avoid judgment, rejection, banishment, discrimination, or reputational fallout.

SPECIFIC FEARS THAT MAY DRIVE THE NEED FOR SECRECY: Being Taken Advantage of, Being Unsafe, Certain Kinds of People, Persecution, Putting Oneself out There, Trusting Others

HOW THIS SECRET COULD HOLD THE CHARACTER BACK

Causing friction with loved ones who don���t agree with the bias

Feeling guilt and shame over what their dark, biased thoughts say about who they are

Being deprived of an enriching or helpful relationship with someone from the biased group

Missing out on the opportunity to gain allies or share resources

The character���s perspective always being limited to align with people who think like them

BEHAVIORS OR HABITS THAT HELP HIDE THIS SECRET

The character entertaining the bias in their mind but not speaking it aloud

The character gravitating toward people who think like them

Justifying their reasons for not engaging with the people they���re biased against

Expressing support for those people but not offering them the same opportunities the character would offer to others

Mentally using labels for certain people but not verbally referring to them that way

ACTIVITIES OR TENDENCIES THAT MAY RAISE SUSPICIONS

Making jokes about the people they distrust

Passive-aggressiveness (backhanded compliments, talking about a member of this group behind their back, etc.)

Not questioning gossip and rumors that cast certain people in a negative light

Not requiring proof of wrongdoing to the same degree the character requires it from other people

Standoffish behavior around this group

SITUATIONS THAT MAKE KEEPING THIS SECRET A CHALLENGE��

Making jokes about the people they distrust

Passive-aggressiveness (backhanded compliments, talking about a member of this group behind their back, etc.)

Not questioning gossip and rumors that cast certain people in a negative light

Not requiring proof of wrongdoing to the same degree the character requires it from other people

Standoffish behavior around this group

Other Secret Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Secret Thesaurus Entry: An Undisclosed Bias appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 9, 2024

A Description Database for Character Relationships

No matter what genre you write, your characters–and their relationships–are the heart of a story. In fact, relationships help us explore our characters’ most meaningful layers while providing readers with the context they need to understand why each character thinks and acts the way they do.

Think about how we all behave in the real world. This looks a bit different depending on who is around, right? It’s no different for a character. Their decisions and choices will be shaped by the type of bond they have with someone. Is the relationship close, or not? Healthy or dysfunctional? Do they play a positive role (a friend, ally, or supporter) or does it run along the lines of something darker, like a rival, enemy, or detractor?

A character’s best and worst qualities may be on display at different times in a relationship, but even better, the type of connection your character has to someone will allow you to seed juicy, show-not-tell clues in your story about their motivations, insecurities, fears, needs, and vulnerabilities.

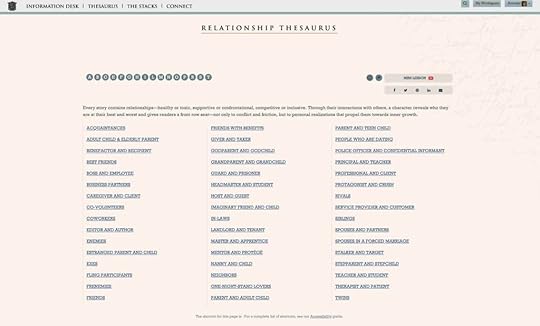

Relationships come in all shapes and sizes, so Becca and I have built a thesaurus of different common types so you can write them with authority. You can find it at One Stop for Writers, as part of our enormous show-don’t-tell THESAURUS.

The Relationship Thesaurus will help you brainstorm character interactions that feel true to life so you can write them into the story. You’ll also find plenty of ideas on how each relationship can develop your characters and further the plot.

If you’d like a peek at this thesaurus, visit these entries at One Stop for Writers: RIVALS, IN-LAWS, and PROTAGONIST AND CRUSH.

If this is the first time you’ve heard about our THESAURUS Database at One Stop for Writers, think of it like our books on steroids. We’ve released 10 thesaurus books to date, but at One Stop for Writers, the database has 18 thesaurus topics…so far.

Speaking of One Stop for Writers, Don’t Forget…

It’s our birthday!

One Stop for Writers is turning 9 this week, and we’re celebrating with a nice 25% discount on any plan.

If you like, grab this code:

HAPPY9

And follow the instructions below to redeem this discount!

To use this code:

Sign up or sign in. Choose any paid subscription (1-month, 6-month, or 12-months) and add this code: HAPPY9 to the coupon box.Once activated via the button, a one-time 25% discount will apply onscreen.Add your payment method, check the Terms box, and then hit the subscribe button.New to One Stop for Writers? Join Becca for a quick tour to see how our resources and tools can help you reach your creative goals.

The post A Description Database for Character Relationships appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 7, 2024

Happy 9th Birthday, One Stop for Writers (Save 25%)

One Stop for Writers‘ BIRTHDAY WEEK is here!

Nine years ago, Becca and I stepped outside our world of book-making and opened the doors of One Stop for Writers, a site filled with one of a kind tools and resources to make writing easier. Year by year, the toolbox at One Stop for Writers has grown and we’ve had the pleasure of helping writers all over the world. We love being part of other writers’ journeys!

25% off all plansTo celebrate NINE YEARS, we’ve cooked up a discount. Whether you’re new to One Stop for Writers or you’ve been using it since the very beginning, grab this code to access our arsenal of tools for less:

HAPPY9

To use this code:

Sign up or sign in. Choose any paid subscription (1-month, 6-month, or 12-months) and add this code: HAPPY9 to the coupon box.Once activated via the button, a one-time 25% discount will apply onscreen.Add your payment method, check the Terms box, and then hit the subscribe button.

And that’s it!

Get ready to put the largest show-don’t-tell database available to writers & the rest of our incredible storytelling tools to work!

New to One Stop?If you’re not familiar with One Stop for Writers, join Becca for a virtual tour. She’ll show you how our resources can help you write stronger fiction faster.

The post Happy 9th Birthday, One Stop for Writers (Save 25%) appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 4, 2024

Character Thesaurus Entry: Using a False Identity

What secret is your character keeping? Why are they safeguarding it? What’s at stake if it’s discovered? Does it need to come out at some point, or should it remain hidden?

This is some of the important information you need to know about your character’s secrets���and they will have secrets, because everyone does. They’re thorny little time bombs composed of fear, deceit, stress, and conflict that, when detonated, threaten to destroy everything the character holds dear.

So, of course, you should assemble them. And we can’t wait to help.

This thesaurus provides brainstorming fodder for a host of secrets that could plague your character. Use it to explore possible secrets, their underlying causes, how they might play into the overall story, and how to realistically write a character who is hiding them���all while establishing reader empathy and interest.

Maybe your character. . .

Uses a False IdentityABOUT THIS SECRET: A character who has made regrettable choices may need to distance themselves from their old life through a false identity. Perhaps they���re wanted by police, they tried to shake down a vengeful enemy, or they���ve adopted an alter ego to hide criminal behavior. This entry will focus on nefarious reasons for living under a false name.

SPECIFIC FEARS THAT MAY DRIVE THE NEED FOR SECRECY: Being Attacked, Being Judged, Being Returned to an Abusive Environment, Being Unsafe, Death, Government, Losing Autonomy, Losing One’s Social Standing, Losing the Respect of Others, Persecution

HOW THIS SECRET COULD HOLD THE CHARACTER BACK

Being unable to have open, honest, and trusting relationships (lest someone finds out)

Needing to avoid certain places, people, and situations where they might be recognized

Never feeling truly safe or at ease (always looking over their shoulder)

Being restricted to activities that will not require a thorough document check

Having to choose a job for its anonymity rather than an interest or skill

BEHAVIORS OR HABITS THAT HELP HIDE THIS SECRET

Changing their appearance

Being skilled at lying and deception

Aligning with the expectations of others

Moving from place to place, being nomadic

Moving far away from where they used to live

ACTIVITIES OR TENDENCIES THAT MAY RAISE SUSPICIONS

Odd behaviors (a tendency to not touch things, pay only with cash, etc.)

Becoming morally flexible when certain opportunities come up

Being caught in a lie, especially over something that seems silly to lie about

A vice being discovered (such as gambling or drug use) that doesn���t fit who they claim to be

Pointing out things the average person wouldn���t know: See that guy? Stay away from him–he���s a pickpocket.

SITUATIONS THAT MAKE KEEPING THIS SECRET A CHALLENGE

Marrying into a family who have members in law enforcement

Witnessing a crime (or being the victim of one) and being questioned by police

Winning a prize unexpectedly, becoming the focus of local attention

Running into someone from their old life

Other Secret Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Thesaurus Entry: Using a False Identity appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Character Thesaurus Entry: Uses a False Identity

What secret is your character keeping? Why are they safeguarding it? What’s at stake if it’s discovered? Does it need to come out at some point, or should it remain hidden?

This is some of the important information you need to know about your character’s secrets���and they will have secrets, because everyone does. They’re thorny little time bombs composed of fear, deceit, stress, and conflict that, when detonated, threaten to destroy everything the character holds dear.

So, of course, you should assemble them. And we can’t wait to help.

This thesaurus provides brainstorming fodder for a host of secrets that could plague your character. Use it to explore possible secrets, their underlying causes, how they might play into the overall story, and how to realistically write a character who is hiding them���all while establishing reader empathy and interest.

Maybe your character. . .

Uses a False IdentityABOUT THIS SECRET: A character who has made regrettable choices may need to distance themselves from their old life through a false identity. Perhaps they���re wanted by police, they tried to shake down a vengeful enemy, or they���ve adopted an alter ego to hide criminal behavior. This entry will focus on nefarious reasons for living under a false name.

SPECIFIC FEARS THAT MAY DRIVE THE NEED FOR SECRECY: Being Attacked, Being Judged, Being Returned to an Abusive Environment, Being Unsafe, Death, Government, Losing Autonomy, Losing One’s Social Standing, Losing the Respect of Others, Persecution

HOW THIS SECRET COULD HOLD THE CHARACTER BACK

Being unable to have open, honest, and trusting relationships (lest someone finds out)

Needing to avoid certain places, people, and situations where they might be recognized

Never feeling truly safe or at ease (always looking over their shoulder)

Being restricted to activities that will not require a thorough document check

Having to choose a job for its anonymity rather than an interest or skill

BEHAVIORS OR HABITS THAT HELP HIDE THIS SECRET

Changing their appearance

Being skilled at lying and deception

Aligning with the expectations of others

Moving from place to place, being nomadic

Moving far away from where they used to live

ACTIVITIES OR TENDENCIES THAT MAY RAISE SUSPICIONS

Odd behaviors (a tendency to not touch things, pay only with cash, etc.)

Becoming morally flexible when certain opportunities come up

Being caught in a lie, especially over something that seems silly to lie about

A vice being discovered (such as gambling or drug use) that doesn���t fit who they claim to be

Pointing out things the average person wouldn���t know: See that guy? Stay away from him–he���s a pickpocket.

SITUATIONS THAT MAKE KEEPING THIS SECRET A CHALLENGE

Marrying into a family who have members in law enforcement

Witnessing a crime (or being the victim of one) and being questioned by police

Winning a prize unexpectedly, becoming the focus of local attention

Running into someone from their old life

Other Secret Thesaurus entries can be found here.

Need More Descriptive Help?

Need More Descriptive Help?While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the One Stop for Writers THESAURUS database.

If you like, swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Thesaurus Entry: Uses a False Identity appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 3, 2024

How to Identify Your Writing Business Relationship Type

Try this: Think about your writing or writing business as a partner.

Start by giving it a name. What would you call your writing (if you haven���t started selling yet) or writing business (if you are selling books)?

Mine is ���Dolores,��� because she���s demanding. (If your name is Dolores, my apologies!) During all my waking hours, she’s babbling on about what I need to do for my next book, my author platform, my website, and more. She’s a slave driver and never lets up enough to give me a break.

Once you have a name, it���s time to see what sort of partnership the two of you have.

Do that, and you can better understand what the problems are and what you might need to change so you feel more energized, motivated, and successful.

Let me give you some examples. I based them on well-known movies just for fun.

Five Writer/Writing Business Relationship Types1. Pride and Prejudice: Too Sweetly Perfect!You are like Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy, perfectly suited for one another. You have your strengths and your writing business has its strengths, and together you are the perfect combination. You feel motivated, excited, and eager for tomorrow, and if problems arise, you have faith that you’ll solve them together.

Key Characteristics:

Strong partnership that regularly produces great products (books and related writing business items).Thriving relationship that gives both partners energy, motivating each to be at their best.Both sides give back���you to your writing business, and the writing business back to you (via positive feedback, reviews, income, and growth).Couples Counseling: Keep doing what you���re doing and enjoy the ride! It may also be wise to establish some checkpoints to make sure you both continue to thrive.

2. Titanic: Sweet but Doomed Because One of You Is Dying for the OtherIf you have a Titanic relationship, you know it, because one of you is dying. Maybe it���s the writer. Her books are doing well, but she is exhausted, burned out, and ready to quit. Or perhaps it’s the writing business. Subscribers are down, reviews aren���t good, money is near nonexistent, and it feels like a deep dark hole. The iceberg is looming, and the ship is headed right for it.

Key Characteristics:

The partnership is unbalanced���one of you is giving too much and the other is taking too much without giving back.One of you is exhausted and running on fumes while the other keeps demanding: give give give!A sense of doom surrounds you, and you wonder if you are cut out for this writing thing.Couples Counseling: Step back and assess. Which of you is giving too much? Usually, it���s the writer. You���re slaving away to the point of exhaustion, but your business isn���t giving back. You���re not getting the rewards you hoped for, whether that be money, positive feedback, recognition, or an expanding readership.

If you���d like to earn more money, stop doing anything that is not earning money and regroup. Educate yourself on how to earn money as a writer, then restart your efforts incorporating that learning.

If you���d like to grow your readership, stop everything you���re doing that���s not working. Educate yourself on how to do that, then start again.

The point is to clearly identify the issue so you can direct more of your time and energy toward those things that will bring you the rewards you crave.

3. Alien: You Started Out Curious but Now You Want to Run and Hide

Things were great in the beginning. You were writing and building your business and feeling wonderful. But then you submitted your book and were rejected, or you published your book to poor sales or lackluster reviews. You thought this partnership was going to be great, but now you���re having a hard time looking (Dolores) in the eye.

Key Characteristics:

The partnership is on a tenuous footing. Things haven’t gone like you wanted them to and you’re thinking of getting out.You feel overwhelmed at the prospect of trying to figure out how to kill the monster that���s tearing everything up.You���ve read books and taken workshops, but self-doubt is consuming you. You���re not sure you���ll get out of this alive.Couples Counseling: Take a deep breath and realize that every partnership goes through dark times. Failure is part of the deal. Try to relax, take a break, then try again. Few succeed their first time out���be compassionate with yourself, reconnect with ���why��� you���re writing, and believe in your talent and ability to improve.

4. Harry Potter: You Can Do Magic but There’s an Unknown Problem That Will Not Be NamedYou love the writing, and people love your writing! Those who read your stories have nothing but wonderful things to say, and you know this is where you’re meant to be. Why then, aren’t your stories selling? Why can’t you grow your subscriber list? What demon is in the shadows obstructing your hero’s journey?

Key Characteristics:

Some parts of the partnership feel magical���they keep you motivated and excited.But something is still not working right and you���re not sure what.Because you���re lacking some true markers of success (lots of readers, high sales numbers), you question whether you���re just deluding yourself that writing can create a viable future for you.Couples Counseling: If you���re doing everything you should be doing���updating your website, creating an attractive freebie for your subscribers, getting yourself out there on social media and podcast interviews���and you���re still not reaching the goals you���ve set for yourself, reach out to a mentor. A fresh set of eyes can often see more clearly what needs to change to root out this unnamed demon!

5. ET: Everything Was Exciting but Then the Alien Went Home and Now You���re BoredYou got that three-book deal, or your series of romance novels are selling well. The reader feedback is good, the money is coming in, and the two of you are on your way! But there���s one big problem: you���re bored. What you���re doing no longer excites you. Your creativity waddled onto the spaceship and left. Your writing business partner wants you to keep it up because, um, success! But you don���t know if you can muster the motivation.

Key Characteristics:

By all indications, the business is going well, but the writer is not excited about it anymore.The writer may feel guilt or remorse for her feelings���she should be happy for the success she���s experiencing.The writer is starting to see writing and everything related to it as a chore.Couples Counseling: It���s time to go looking for another alien���or at least a way to make writing fun again. If you���re locked into a publishing contract, maybe you can work on something new on the side. If the business tasks are dragging you down, perhaps you could hire an assistant. No matter what, you have to find a way to infuse excitement back into this partnership or it���s likely to eventually dissolve.

What Story Describes Your Relationship?I hope these examples gave you some ideas for how you might describe your writing business relationship. I���ve found that using your imagination to look at it creatively can often reveal new insights about how to do things better. The more fun you can have with it, the more ideas will come to mind.

Note: Colleen offers coaching on breaking through stuck spots and balancing writing with life. Get your FREE report: The Secret to Powerful Writing: Embracing Your Shadows.

The post How to Identify Your Writing Business Relationship Type appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

October 1, 2024

Meet Our Resident Writing Coaches

I love being the Writers Helping Writers Blog Wizard���and am honored to work closely with the Resident Writing Coaches. They���re all talented, generous authors who share their wisdom to help take your writing to the next level. I’ve learned so much from them, and have a feeling you have, too!

This is the 9th year of our popular Resident Writing Coach program where we feature writing experts through a series of four blog posts scattered throughout the year. We bring in a mix of expertise, so you benefit from different voices and perspectives from all over the world.

Each year we have some new coaches and some returning, so let me first say goodbye to the wonderful Sue Coletta and September C. Fawkes. We hope you’ll both join us again in the future and greatly appreciate all you have shared with us.

I���m excited to welcome back an amazing Resident Writing Coach. Please give a warm welcome to���

Christina Delay is an award-winning author of psychological suspense, as well as mythological-based fantasy written under the pen name Kris Faryn. A wanderer by heart, Christina���s latest adventure has led her and her family to the southwest of France. When not planning their next quest, Christina can be found writing in her garden, hosting writing retreats, sneaking in a nap, or convincing her patooties to call her Empress. If you love books about complex characters who never know when to quit, with a good bit of will-they or won���t-they tension, check out her books.

You can find Christina on Facebook, Instagram, her Website, and Amazon.

You can find Christina’s posts here.

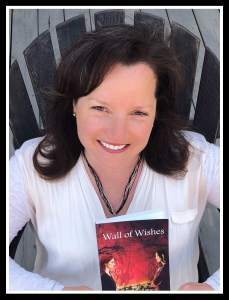

I’m also excited to introduce a new Resident Writing Coach with post topics I can’t wait to share with all of you. Please welcome…

Jenny Hansen provides brand storytelling, LinkedIn coaching, and copywriting for accountants and financial services firms by day. By night, she writes humor, memoir, women���s fiction, and short stories. After 20+ years as a corporate trainer, she���s delighted to sit down while she works.

As a co-founder of Writers In the Storm, Jenny has been sharing loads of love and how-to with writers since 2010. WITS, as it is affectionately known, has been named one of the 101 Best Websites for Writers by Writer���s Digest off and on since 2014. They post each week on writing craft, inspiration, and the up-and-down rollercoaster of this writing life.

Jenny is hard at work revising a memoir on her recent journey with cancer. Some have characterized her writing style as ���get busy laughing, or get busy crying.���

You can find her online at Writers In the Storm, Facebook or Instagram.

In addition to our new coaches, we���re thrilled to have these returning masterminds���

Lucy V. Hay is a script editor, author and blogger who helps writers. She���s been the script editor and advisor on numerous UK features and shorts & has also been a script reader for 20 years, providing coverage for indie prodcos, investors, screen agencies, producers, directors and individual writers. She���s also an author, publishing as both LV Hay and Lizzie Fry. Lizzie���s latest, a serial killer thriller titled The Good Mother is out now with Joffe Books, with her sixth thriller out in 2024. Lucy���s site at www.bang2write.com has appeared in Top 100 round-ups for Writer���s Digest & The Write Life, as well as a UK Blog Awards Finalist and Feedspot���s #1 Screenwriting blog in the UK (ninth in the world.). She is also the author of the bestselling non-fiction book, Writing & Selling Thriller Screenplays: From TV Pilot To Feature Film (Creative Essentials), which she updated for the streaming age for its tenth anniversary in 2023.

You can find Lucy���s posts here.

Marissa Graff has been a freelance editor and reader for literary agent Sarah Davies at Greenhouse Literary Agency for over five years. In conjunction with Angelella Editorial, she offers developmental editing, author coaching, and more. She specializes in middle-grade and young-adult fiction but also works with adult fiction.

Marissa feels if she���s done her job well, a client should probably never need her help again because she���s given them a crash-course MFA via deep editorial support and/or coaching. Connect with Marissa on her Website, Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

You can find Marissa���s posts here.

Colleen M. Story is a novelist, freelance writer, writing coach, and speaker with over 20 years in the creative writing industry. Her newest novel, The Curse of King Midas, is forthcoming in 2024, and has already been recognized as a top-ten finalist for the Claymore Award. Her novel The Beached Ones came out in 2022 with CamCat Books, while Loreena���s Gift, was a Foreword Reviews��� INDIES Book of the Year Awards winner, among others.

Colleen has written three books to help writers succeed. Your Writing Matters is the most recent, and was a bronze medal winner in the Reader Views Literary Awards (2022). Writer Get Noticed! was a gold-medal winner in the Reader���s Favorite Book Awards and a first-place winner in the Reader Views Literary Awards (2019). Overwhelmed Writer Rescue was named Book by Book Publicity���s Best Writing/Publishing Book in 2018. You can find free chapters of these books here.

Colleen offers personalized coaching plans tailored to meet your needs. If you���d like to work on-one-one with an experienced writing coach, check out her flexible and affordable options.

Colleen frequently serves as a workshop leader and motivational speaker, where she helps attendees remove mental and emotional blocks and tap into their unique creative powers. Find her at Writing and Wellness, Author Website, YouTube, Twitter, LinkedIn, Goodreads, BookBub and Instagram.

You can find Colleen���s posts here.

Jami Gold, after muttering writing advice in tongues, decided to become a writer and put her talent for making up stuff to good use, such as by winning the 2015 National Readers��� Choice Award in Paranormal Romance for her novel Ironclad Devotion.

To help others reach their creative potential as well, she���s developed a massive collection of resources for writers. Explore her site to find worksheets���including the popular Romance Beat Sheet with 80,000+ downloads���workshops, and over 1000 posts on her blog about the craft, business, and life of writing. Her site has been named one of the 101 Best Websites for Writers by Writer���s Digest.

Find Jami at her website, Twitter, Facebook, Goodreads, BookBub, and Instagram.

You can find Jami���s posts here.

Lisa Poisso works with new and emerging querying and self-publishing writers. A classically trained dancer, her approach to writing is likewise grounded in structure, form, and technique as doorways to freedom of movement on the page. She���s an energetic proponent of one-on-one feedback to accelerate the learning curve of writing fiction. Her Accelerator coaching fast-tracks authors through structure and technique while nurturing the potential of their early drafts.

Lisa is a degreed journalist and a veteran of decades of award-winning work in magazine editing and journalism, content writing, and corporate communications. Her coaching and editorial studio is staffed by an industrious team of #45mphcouchpotato greyhounds. Visit her Linktree for help with your early steps as a writer, join the Clarity for Writers community at Substack, and download a free Manuscript Prep guide. Connect with Lisa at LisaPoisso.com and on Instagram, Facebook, and X/Twitter.

You can find Lisa���s posts here.

Suzy Vadori is the award-winning author of The Fountain Series and is represented by Naomi Davis of Bookends Literary Agency. She is a certified Book Coach with Author Accelerator and the founder of the Wicked Good Fiction Bootcamp. Suzy breaks down concepts in writing into practical steps, so that writers with big dreams can get the story exploding in their minds onto their pages in a way that readers will LOVE.

In addition to her online courses, Suzy offers 1:1 Developmental Editing and Book Coaching services, and gives practical tips for writers at all stages on her vlog.

Find Suzy on her website, YouTube, Facebook, Free Inspired Writing Facebook Group, Instagram, and Tiktok.

You can find Suzy���s posts here.

Michelle Barker is an award-winning author, editor, and writing teacher who lives in Vancouver, BC. Her newest book, coauthored with David Griffin Brown, is Immersion and Emotion: The Two Pillars of Storytelling. Her novel My Long List of Impossible Things, came out in 2020 with Annick Press. She is the author of The House of One Thousand Eyes, which was named a Kirkus Best Book of the Year and won numerous awards including the Amy Mathers Teen Book Award. She���s also the author of the historical picture book, A Year of Borrowed Men, as well as the fantasy novel, The Beggar King, and a chapbook, Old Growth, Clear-Cut: Poems of Haida Gwaii. Her fiction, non-fiction and poetry have appeared in literary reviews around the world.

Michelle holds an MFA in creative writing from UBC and has been a senior editor at The Darling Axe since its inception. She loves working closely with writers to hone their manuscripts and discuss the craft. You can find Michelle on Twitter and GoodReads.

You can find Michelle���s posts here.

TipsIf you want to browse past Resident Writing Coach posts, click here.

Love a post? Click on the name up top to see all the posts from that person.

Check out all the Resident Writing Coach bios! You���ll find:

Editing and coaching servicesFree support through online groupsHelpful resourcesDon���t forget to follow them on social media for even more tips and updates!

Here���s to another year of amazing posts. Please give a warm welcome our Resident Writing Coaches.

Pssst���when you comment on their posts, they reply to you! So please share your thoughts and ask questions throughout the year. Angela, Becca and I love working with the coaches. They���re an incredible asset to the Writers Helping Writers blog.

If there���s a topic you���d like help with, please add it in the comments so hopefully one of our Resident Writing Coaches will post about it.The post Meet Our Resident Writing Coaches appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 28, 2024

Character Secret Thesaurus Entry: No Longer Loving a Partner

What secret is your character keeping? Why are they safeguarding it? What’s at stake if it’s discovered? Does it need to come out at some point, or should it remain hidden?

This is some of the important information you need to know about your character’s secrets���and they will have secrets, because everyone does. They’re thorny little time bombs composed of fear, deceit, stress, and conflict that, when detonated, threaten to destroy everything the character holds dear.

So, of course, you should assemble them. And we can’t wait to help.

This thesaurus provides brainstorming fodder for a host of secrets that could plague your character. Use it to explore possible secrets, their underlying causes, how they might play into the overall story, and how to realistically write a character who is hiding them���all while establishing reader empathy and interest.

Because everyone has secrets. What’s your character hiding?

No Longer Loving a PartnerABOUT THIS SECRET: Breaking up is hard to do���especially when the lack of feeling in a long-term relationship is one-sided. Many would rather suffer in silence in a romantic relationship than hurt the other person, break up, or buck cultural pressures. And when peripheral people, like children, would also be affected…there are many reasons a character might choose to keep their ho-hum feelings under wraps.

SPECIFIC FEARS THAT MAY DRIVE THE NEED FOR SECRECY: Becoming What One Hates, Being Judged, Being Separated from Loved Ones, Change, Conflict, Humiliation, Isolation, Letting Others Down, Losing Financial Security, Losing One’s Social Standing, Losing the Respect of Others

HOW THIS SECRET COULD HOLD THE CHARACTER BACK

Being dissatisfied in one of the most important relationships they could have

Being unable to pursue true love with someone else

Not enjoying sex or other forms of intimacy in the relationship

The character becoming insecure because they think something is wrong with them

Dishonesty with the partner making dishonesty with others more natural, generating conflict in other relationships

BEHAVIORS OR HABITS THAT HELP HIDE THIS SECRET

Continuing to profess emotions they don���t feel

Being overly attentive to the partner

Refusing to even look at or talk to other people the character might be attracted to

Speaking about the partner in glowing, exemplary terms

ACTIVITIES OR TENDENCIES THAT MAY RAISE SUSPICIONS

Losing track of the lies they���ve told and getting caught in deception

Making excuses to avoid physical intimacy

Working long hours

Staying busy with activities the partner isn���t involved in

Signs of emotional involvement with someone else

SITUATIONS THAT MAKE KEEPING THIS SECRET A CHALLENGE

Having to attend couples therapy

Having to plan for and celebrate an important marriage anniversary

Meeting someone the character wants to pursue a relationship with

Growing resentment and dissatisfaction

The partner becoming needy or clingy, needing extra affirmation and attention from the character

While this thesaurus is still being developed, the rest of our descriptive collection (18 unique thesauri and growing) is accessible through the��One Stop for Writers��THESAURUS database.

Intrigued? Swing by and check out the video walkthrough for this site, then give our Free Trial a spin.

The post Character Secret Thesaurus Entry: No Longer Loving a Partner appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1023 followers