Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 19

August 27, 2024

How to Fix a Boring Main Character and Save Your Story

Are you struggling with a boring main character? Are you afraid that he or she is limiting your story���s potential?

This happened to me with my most recent release, “The Curse of King Midas.” Here’s how I not only fixed the problem but created a character powerful enough to spawn a whole series of historical fantasy books.

I Was Stuck with a Boring Main CharacterI wrote ���The Curse of King Midas��� because a friend asked me to.

Usually, my main character is already there when I write a story. But this time, it was different.

My friend was thinking of creating a musical on the well-known Midas myth. But he knew that the best musicals were based on books. Having read some of my previous novels, he asked if I might like to write it.

I told him I���d give it a try. I was concerned, though. I didn’t care for King Midas. In the myth, he’s not a very likable character. Driven by greed, he wishes for the touch of gold, but soon discovers it���s more of a curse than a gift. Ultimately, he begs for the curse to be lifted. The god Dionysus agrees, and all is well.

Ho-hum. Who wants to write about him? Not me.

Looking for inspiration, I researched the myth. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that King Midas was a real person who ruled the Kingdom of Phrygia in the 700s B.C. That blew my mind! Suddenly my main character had a lot more to him.

I uncovered many more historical treasures about this real king and dove confidently into the story.

Unfortunately, my troubles with Midas weren���t over.

My Main Character Was a GhostIn the beginning, I loved writing the story. The characters came to life: King Midas��� two children, his three advisors, his sworn enemy, and the wandering rogue with a secret connection to both kings.

It was all happening on the page in a fun and exciting way, with King Midas at the forefront.

Except he wasn���t. He was like a paper doll, thin and faceless. He was fashioned after Sean Connery. Then Ed Harris. Then Daniel Craig. Then Christian Bale. Nothing worked.

I kept writing scene after scene, but Midas only went through the motions, as hollow as a bamboo tree.

By the end of the first draft, I was getting worried. Despite my best efforts, Midas wasn���t coming through. He was the main character, but the only one who felt soulless on the page. I didn���t care about him, which meant the reader wasn’t going to care about him either.

What Finally Brought King Midas OutHere���s what helped me���three steps that brought King Midas into the light.

Observe him interacting with other characters.I don���t outline my stories. I discover the plot and the characters as I go. So despite my troubles with Midas, I just kept writing.

That meant that Midas was regularly interacting with these other characters, even though I wasn���t sure who he was. The other characters, meanwhile, were delightfully clear. They came through like people I���d known all my life, fully fleshed out and real.

Writing and editing the scenes where Midas appeared with these other characters helped to gradually woo him out of the shadows. It was as if their authenticity was forcing him to be more authentic, too.

Figure out what he really cared about.In the myth, Midas cares about wealth. But I couldn���t relate to that, and we all know that we can���t write convincingly about things we can���t relate to���particularly not for an entire novel.

That left me to figure out what my Midas cared about. The first thing had to be his daughter. He cares about her even in the original myth, so I started with that.

As king, he provides for his daughter and wants to keep her safe. I built a few convincing scenes showing his real feelings for her, but it wasn’t enough to fully understand him. His relationship with his daughter was only a small part of him.

I turned to his interactions with his son. That helped too, because I learned how much Midas cared about his son and wanted to see him prosper.

But it still wasn���t enough. When not interacting with his son or daughter, King Midas still appeared on the page as a stand-in rather than the main act.

Determine what I really cared about.The author Willa Cather is quoted as saying, ���The creative writer can do his best only with what lies within the range and character of his deepest sympathies.���

In other words, we can only write convincingly about those things that touch us deeply. Greed isn���t one of those things for me. Neither is the desire to provide for family or grow an empire.

But personal loss does.

I don’t remember quite how it happened���the idea for the prologue. But one day, somewhere in the middle of draft 3, it was just there���a slice of King Midas��� history when as a child. In a tragic attack, he lost everything he cared about.

Suddenly my flat and boring King Midas was a wounded, angry man who despite having risen to great heights, was consumed with the desire for revenge against the man who had stolen everything from him.

Finally, he became real. This man, I could care about, which meant that finally, I had created a character that readers could care about too.

Bring Your Boring Main Character Out of the Shadows

If you outline your story before you start, you may be able to create a character based on a set of characteristics and run with that. As a discovery writer, though, I lose interest in that approach and struggle to achieve the originality I desire. I have to write my way through to figure out who my characters are.

Usually, they come through fairly easily. This time was different because I was assigned a character to work with���a character I normally would not have chosen. I’m so glad, though, because by using the three methods listed above, I found my way to a new and original King Midas that I���m proud of.

Don���t give up on your boring main character. Give her time, watch her interact with the other characters, and dig deep into her emotions���and yours���and gradually, she���ll come out of the shadows as a much more authentic and interesting person.

Note: August is Colleen���s birthday month, so in celebration, she���s offering The Curse of King Midas ebook for only 99 cents! Get your copy here at that price for a limited time.

The post How to Fix a Boring Main Character and Save Your Story appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 22, 2024

What Characterization Detail Gives Your Protagonist More Depth?

Every writer wants to write a character who stands out, drives the story to interesting places, and captures the reader’s heart. Why?

Because characters with depth sell books.

And of course, the key to creating someone who readers connect to comes down to knowing them inside and out, and carefully choosing each detail about them so each piece of characterization – their personality, experiences, emotional wounds, motivations, beliefs, struggles, fears, needs, and all the rest – weaves together into a meaningful tapestry.

One area of characterization that is often underutilized, yet oh-so-powerful, is the choice of job they do. Whether the work is so suited to them, it feels like their calling in life, or they chose it only because it pays the bills, their choice reveals their inner layers in an ultimate display of show, don’t tell.

In the case of a job they love and find fulfilling, readers will immediately gain insight about their core values, what gets them excited and motivated, and the skills that make them good at what they do. Let’s try a few:

An Animal Rescue Worker will love animals, have a lot of compassion, and be the type of person to step in and help others in need. They abhor cruelty and unfairness, and seek to stand against it. They will be the giving sort, ready to step in, stay at work late, go in early. They will have incredible patience, and be fixers, motivated by the chance to transform an animal’s life so they go on to find the love and happiness they deserve.

A Funeral Director will be someone who is empathetic, respectful, and carry the belief that all people, regardless of who they are, deserve a dignified end to their journey in this world. They are obviously comfortable with death, have a strong work ethic, handing long hours and an unfixed schedule, because a person’s passing is unpredictable. They will be detailed-oriented, and take great care, knowing the families they serve are placing trust in them to serve in this final way.

A Reporter is someone who pays attention, always searching for the story and how to convey information in a way that makes it accessible and interesting to their audience. They will seek to report in a niche they are passionate about, providing clues as to what they believe in, care about, or have deep interests in. They are investigative, detail-oriented, and good at putting together pieces that others may miss. They will be good at connecting with people, getting them to open up and share, but their focus and dedication to the work may mean the job comes first, and their real-world relationships are not as strong as the effort they put into them is unpredictable.

What about a job that the character may not love, but it fits their life circumstances?The possibilities are endless.

A character doing a job they don’t enjoy (maybe a personal shopper or taxi driver tells readers that paying the bills comes before personal satisfaction because they are responsible.

A character working a manual job as a janitor may do so to avoid the stress of the career they trained for (an emergency dispatcher).

And what about a character that chooses a job no one wants to do (pest control technician)? Maybe it’s the perfect fit for someone in a witness protection program who values privacy and anonymity above prestige or a hefty paycheck.

Bottom line?

Bottom line?A character’s job isn’t a

throwaway detail.

It’s worth the time to pick a job that reflects the exact story you want readers to know about your character, personality, background, and life circumstances. If you need help brainstorming the right career, we have a giant list of occupations HERE.

The post What Characterization Detail Gives Your Protagonist More Depth? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 20, 2024

Creating Suspense in any Genre

When we think about suspense in writing, we naturally leap to thrillers and mysteries, genres that are known for suspense and rely on it. But that doesn���t mean the rest of us are off the hook. Suspense is an essential element in any story. Whenever we create a feeling of anticipation (or dread) that something dangerous or terrible is about to happen, we increase the odds that our reader will keep turning pages.

There���s suspense in romance: will the boy win over his crush?

There���s suspense in humor: will the joke land?

There���s even suspense in picture books: what will happen the third time little Johnny looks under the bed?

But suspense alone isn���t enough to keep your reader engaged.

Suspense Depends on ConnectionThe reader has to care about the character to care about what happens to them. If some stranger down the road is in danger of losing their job, it���s objectively sad but it probably won���t keep you awake at night. If it���s your partner, however, that���s a different story. You have a connection to that person. You care about what happens to them. You���re invested in the outcome of that problem. What will happen tomorrow at that big meeting? You can barely sleep thinking about it.

Just so in fiction. As an author, your primary job in the opening of a novel or story is to create connection. You want your reader to bond with the protagonist so that they���re invested in the character���s wellbeing. They care about what happens to them. Once you���ve done that, your job is to make the worst things either happen or threaten to happen so that your reader is on the edge of their seat hoping their beloved character will survive.

This is why it���s never particularly effective to start a novel with a car chase or a fight scene. If we don���t yet care about who these things are happening to, we won���t care how they turn out.

Suspense Depends on Future

Suspense involves the creation of anxiety in the reader over what will happen���not about what���s happening now. What���s happening in the moment involves (or should involve) either tension or conflict. Things are going wrong. Something is off. The character is uneasy. People aren���t getting along.

This is why foreshadowing and suspense go hand in hand. Foreshadowing prepares the ground for future disaster. If you don���t use foreshadowing, either your reader will feel cheated or the plot twists will seem too coincidental. But if you do foreshadow and your reader is paying attention, they���ll see the breadcrumbs and sense where they���re leading and think, No. Not that. Please not that. And voil��, you have created suspense.

Literary agent Donald Maass suggests including tension on every page. That means you should be giving your reader something to worry about on a regular basis. You should especially be doing this at the end of every chapter so that your poor reader cannot shut off the lamp and go to bed (yes, we authors are sadists).

I���m not necessarily talking about cliffhangers. While sometimes these might be appropriate, too many in a row will feel gimmicky. What I���m talking about is the creation of anxiety. The last thing you want at the end of a chapter is resolution. There is only one appropriate place for that: at the end of your novel.

Suspense Depends on RhythmPacing and suspense are soulmates. You want to draw things out just enough to keep your reader hooked. If you take too long to get the job done, they���ll drop off to sleep. If you move too quickly, they might stop caring because you���re not taking the time to develop internal conflict. And internal conflict is what makes readers care.

Suspense Depends on Playing FairI can���t count the number of manuscripts I���ve edited where an author decides to create suspense by purposely withholding information from the reader, even though it doesn���t make sense and in fact breaks POV.

Example: someone asks your protagonist to do them a rather sketchy favor. But you, the author, decide to manufacture false suspense by not revealing what the favor is. This is an example of not playing fair and it breaks POV rules. If we���re in the protagonist���s head and he was present during the conversation with the other person, we should have access to what���s going on.

The suspense should not be in the favor itself; it should be in the fallout. What will happen now that this person has asked your protagonist to do something shady? Will they do it? Should they do it? What will happen if they don���t do it? There���s the real suspense. Simply withholding the dialogue makes the reader feel manipulated.

Suspense Depends on StakesWhat will happen if Tina loses her job? Again, we���re talking about future: anxiety, giving the reader something to worry about. There must be something at stake���consequences if things go wrong. The reader needs to be reminded regularly of what they are. And the consequences have to matter���both to the protagonist and to us.

This means all parties involved must care about how this terrible situation might turn out. Which means, for your protagonist, whatever is going on needs to be personal. Again, not Joe Schmoe down the road but Tina sitting across from you at the breakfast table. Your protagonist should have skin in the game.

Dramatic Irony Can Heighten SuspenseDramatic irony involves putting your reader in the privileged position of knowing more than the protagonist. We know the businessperson they���re getting involved with is actually a con artist. Danger hurtles toward the protagonist and we see it coming���but they don���t. Dramatic irony can be a sharp tool to heighten suspense.

In ConclusionSuspense belongs in every genre. Create connection. Make your reader care about what happens to the protagonist���and then give them things to worry about.

The future is unstable. Be afraid. Be very afraid.

The post Creating Suspense in any Genre appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 14, 2024

Phenomenal First Pages Contest – Guest Editor Edition

Hey, wonderful

writerly people!

It���s time for Phenomenal First Pages, our monthly critique contest. So, if you need help with the beginning of your novel, today’s the day to enter for a chance to win professional feedback.

One winner will receive feedback on their first 20 pages!Entering is easy. All you need to do is leave your contact information on this entry form (or click the graphic below). If you are a winner, we’ll notify you and explain how to send us your pages.

Contest DetailsThis is a 24-hour contest, so enter ASAP.Make sure your contact information on the

entry form

is correct. One winner will be drawn. We will email you if you win and let you know how to submit.Please have your first 20 pages ready in case your name is selected. Format it with 1-inch margins, double-spaced, and 12pt Times New Roman font. You���ll need to supply a

synopsis

(a rough one is fine) so Stuart has context for his feedback.The editor you’ll be working with:Stuart Wakefield

Contest DetailsThis is a 24-hour contest, so enter ASAP.Make sure your contact information on the

entry form

is correct. One winner will be drawn. We will email you if you win and let you know how to submit.Please have your first 20 pages ready in case your name is selected. Format it with 1-inch margins, double-spaced, and 12pt Times New Roman font. You���ll need to supply a

synopsis

(a rough one is fine) so Stuart has context for his feedback.The editor you’ll be working with:Stuart Wakefield

With 26 years in theatre, broadcast media, and coaching under my belt, I have a visceral understanding of what makes stories work, and I���d like to share it with you because writing a novel doesn���t always have to be difficult and daunting, especially if it���s your first time. Understanding the process, getting started, and seeing it all come together can seem like an impossible mountain to climb.

As an Author Accelerator Certified Book Coach, I���m passionate about helping new writers craft stories with passion and purpose, momentum and meaning. I have an MA (Distinction) in Professional Writing, and my debut novel, Body of Water, was one of ten books long-listed for the Polari First Book Prize. My latest novel, Behind the Seams, was a 2021 BookLife Fiction Prize Contest semifinalist.

My first TV show aired on the UK���s Channel 4 in 2023.

So, if you have a story in your heart, just waiting to be shared with the world, I���m here to offer you guidance and support from developing your story right through to pursuing publication. You can find my website, blog, and free self-editing cheat sheet right here: https://linktr.ee/thebookcoach

Sign Up for Notifications!If you���d like to be notified about our monthly Phenomenal First Pages contest, subscribe to blog notifications in this sidebar.

Good luck, everyone. We can’t wait to see who wins!

PS: To amp up your first page, grab our First Pages checklist from One Stop for Writers. For more help with story opening elements, visit this Mother Lode of First Page Resources.

The post Phenomenal First Pages Contest – Guest Editor Edition appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 13, 2024

Use Your Story’s Takeaway (Theme) to Trim Extraneous Content

Writing an entire book is an immensely complex undertaking. Even if you���ve outlined meticulously, you’ll need more ideas than you can possibly imagine to fill the pages of an entire book (50,000 to 100,000 words or beyond, depending on your genre). And what you���ve mapped out in detail in an outline will only fill a portion of this.

Whether you���re writing fiction or pulling from real events for a nonfiction book, as you write, your brain will make decisions about what to include. What comes easily might depend on your mood or what you got up to that day.

When I read about characters making spaghetti while I���m editing draft pages of a writer���s fantasy novel, or a character cleaning their house in detail in a romance, I know instantly that the writer is bringing snippets of their own lives into their pages. Sometimes, these scenes are brilliant writing. Occasionally, the scenes are on point and tie into the rest of the book. But many times, scenes like these have nothing to do with the character���s journey, and they slow the pace of the book to the point a reader might stop reading.

As you���re coming up with ideas and exploring how they fit into your book, it���s easy to lose sight of what you wanted to say to readers in the first place. Instead, while you���re scrambling to fill your pages, you might veer off course, creating a book full of cool things that isn���t what you meant to write at all and will leave readers confused.

I have conversations with writers weekly who want to discuss whether they should add a new idea they just came up with to their book. What they really want is a compass that will tell them if the scene they���re adding is improving or taking away from their reader���s experience. To figure this out, they need to choose a Takeaway.

What Is a Takeaway?The Takeaway you decide on for your book is closely related to what some might call your theme, or the point of your story. As with everything I teach about writing, I like to flip the script, thinking about the reader at every turn, because they���re the ones that you hope will find, read, love, and share your book with others. They���re the ones you���re starting a conversation with when you publish your book, and choosing a Takeaway can help you decide which scenes belong and which ones you should kick to the curb.

To choose a Takeaway for your book, take a step back and ask yourself a simple question: What message do you want readers to take away from your book?

Choosing Your Book���s Takeaway

You don���t have to get too fancy with this. A simple sentence, clich��, tried-and-true saying, or a mantra will do, as long as it resonates with you and it���s what you hope your readers will think about when they���re done. Your Takeaway won���t be shared with the world, it���s just a reference point for you. So don���t sweat making every word in it perfect.

Some examples of Takeaways in books:

Blood is thicker than waterYou can���t accept love until you love yourselfYou get out of life what you put into itYou can choose your Takeaway when you���re planning your book or during your revision stage, whenever you need guidance. To get started, spend 20 minutes brainstorming a list of 5-7 possible Takeaways for the book you���re writing now, then narrow it down to one you���re excited about.

PRO TIPS:

* Choose only one Takeaway per book

* Books in a series may have the same Takeaway for each book, or they may be different

Simple, right? Now here���s the fun part. Once you���ve chosen your Takeaway, you have a way to test every idea or scene that you want to include in your book, to see if it fits.

Note: Choosing a Takeaway doesn���t mean everything in your book will feel the same, or that every character in your book will view the world the same way, which is pushback I often hear from writers who don���t want to be restricted. In fact, your Takeaway will open up multiple directions for your scenes to go while delivering an experience to your reader that feels cohesive and incredibly satisfying (even if they have no idea how you did it ��� that���s the magic and the behind-the-scenes of writing).

With your Takeaway handy, take a look at each scene, event, action, or character���s reaction you want to include in your book. Does it somehow compare, contrast, mirror, challenge, or support your Takeaway? If it does one of these things, it belongs in your book. If it doesn���t? It���s off-topic and will feel out of place to your reader. Cut it.

A Takeaway ExampleLet’s imagine that Blood is Thicker than Water is your Takeaway. Scenes that support this Takeaway will obviously show family bonds that are stronger than anything else in a character���s life.

But��� don���t forget to include ideas and scenes that will compare, contrast, mirror, or challenge this Takeaway, such as:

A subplot showing a dysfunctional family with no loyalty among them, and the resultA character who has no family trying to find their place in the worldA storyline where supporting one���s blood relatives results in disasterA character who feels burdened by their family, even if the relationships benefit themPRO TIP: The Theme & Symbolism Thesaurus at One Stop for Writers explores many popular story themes and thematic statements like the ones above that might work for your story.

You can include any number of ideas that revolve around your Takeaway. Remember, if you have a scene that doesn���t fit this bill, take it out, even if you love it (in writing we call this killing your darlings!). If you dig in your heels and leave it in, your readers will miss out on the incredibly satisfying experience of having everything in your book pointing in the same direction as your plot unfolds, leading readers to love and share your book with others.

Once your Takeaway is woven into every scene, you���ll start to see possibilities and connections you didn���t see before, and readers will be pulled deep into your story. With your Takeaway as a guide to what belongs in your book, your message will come through without you having to hit readers over the head with it, and it will linger long after they reach The End.

And those deleted scenes? You can always release them later as bonus material for your loyal readers, or you can include them in a future book that revolves around a different Takeaway. So they���re never really lost.

Defining your Takeaway and ensuring everything you���ve included in your book aligns or evokes it in some way is the secret sauce that will hold your reader���s attention and push their experience over the top. So keep your Takeaway top of mind while you plan and revise your book to make it as impactful as it can be.

Want more practical tips on writing that you can apply to your book today? Take a listen to my brand new podcast, Show, Don���t Tell Writing .The post Use Your Story’s Takeaway (Theme) to Trim Extraneous Content appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 8, 2024

Story Structure as a Fractal

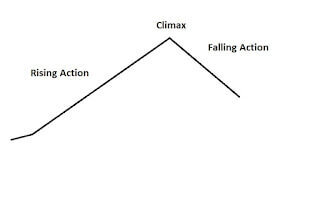

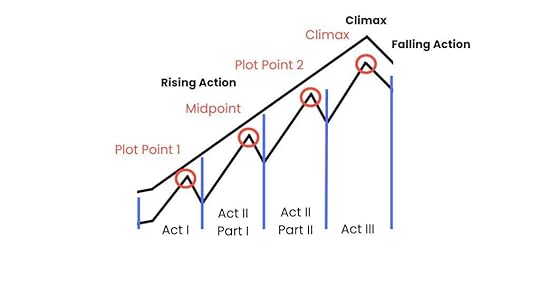

Structure is critical to every story. And it’s highly likely that if you are reading this article, you are familiar with the most basic shape of story structure. This one:

Rising Action:��A character starts with a goal, runs into an antagonist, and struggles through conflict.����

Climax: Eventually that conflict hits a peak, where the protagonist will succeed or fail definitively.

Falling Action: With the conflict resolved, the tension dissipates into falling action, and a new normal is usually established.

This is story’s foundational, basic structure. Nearly every satisfying story follows this structure. But this is still rather simplistic, and you can get more complex and detailed than this.

For one, it’s helpful to know that the climax is also what’s called a “turning point”–it��turns��the direction of the plot. Notice how the story’s “line” in the diagram quite literally, visually turns, from rising action, to falling action at the climax. The plot was going one direction and then��wham–it’s now going a different direction.��

A turning point is also known as a “plot point” or a “plot turn.” So we have three different terms for more or less the same thing. One of the quickest ways to gauge if a turning point has happened, is to ask if the character’s current goal or plan has shifted in some way. If the answer is yes, you likely hit a turning point.

The climax is the biggest, most recognizable turning point in a story, and it most definitely shifts the protagonist’s goal–because he will either definitively achieve (or fail to get) that goal. You can learn more about turning points here.

The climax, however, isn’t the only turning point in a story.

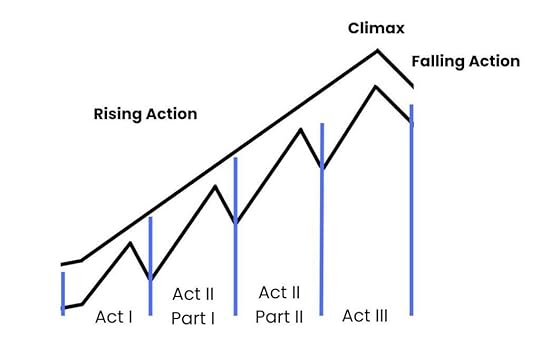

In reality, this basic structural shape works as a fractal or a Russian nesting doll. There are smaller versions of it that exist within the big one.

Just below the narrative arc as a whole, we have another structural unit: acts.

Most commonly, we see stories with three acts. We may view these as beginning, middle, and end.

Frequently, Act II (the middle) will be split in half, because it’s the longest–often taking up 50% of the story. So we have Act II, Part I, and Act II, Part II.

This means, generally speaking, we can divide most stories into quarters.

Act I (Beginning) takes up ~1 – 25% of the story.

Act II, Part I (Middle) takes up ~ 26 – 50%

Act II, Part II (Middle) takes up ~ 51 – 75%

Act III (End) takes up ~76 – 100%

I’m well aware that some writers dislike percentages, but percentages are the quickest way to explain when something should typically happen in a story, and they are just guidelines. Not all stories break down like this, and there is certainly room for variation.

Still, generally speaking, each of these quarters, follows this same shape–it’s just smaller and less pronounced than that of the whole narrative arc.

Each quarter should have a climb, hit a peak, and then have some falling action (which is usually made up of the character’s reaction to what happened at the peak). That peak is a turning point.

For example, in Act I of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the rising action is Harry dealing with the Dursleys and then trying to get the mysterious letter. It hits its peak when Hagrid arrives and reveals “Yer a wizard, Harry.” That’s the major turning point the beginning has been building toward. Notice it shifts Harry’s goal: Now he wants to go to Hogwarts to learn magic (which will take us into Act II).

Commonly, act-level turning points are called “plot points,” so you may have heard of them referred to as “Plot Point 1,” “Plot Point 2,” or the “Midpoint.”

However, in other approaches, they may go by different names. For example, Save the Cat! breaks down like this:

Each one is the major “climactic” plot turn of that quarter.

But this shape goes even smaller.

Inside of acts, we have scenes.

Most scenes should also have the rising action of conflict, the peak of a turning point, and the falling action of the character’s reaction.

Most scenes should also have an antagonist and goal.

The difference is that these things will be even smaller and less pronounced–because they fit inside acts.

For example, in Harry Potter, we have the scene where Harry is trying to find Platform 9 3/4 at King’s Cross–that’s his goal. But he’s met with obstacles: he can’t find the platform, he can’t find anyone to help him, he has to run at a barrier. The turn is Harry successfully getting through that barrier; notice it shifts his goal–because he achieved his scene-level desire. The falling action is him reacting to and taking in the platform.

This basic shape can go even smaller, fitting within passages of scenes, or it can be expanded into something bigger, creating a nice structure for a book series.

This basic shape permeates just about everything.

The post Story Structure as a Fractal appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 6, 2024

Using Your Setting to Characterize

In storytelling, our number one job is to make readers care. We want to ensure that our fiction captivates them on many levels and that our characters seem like living, breathing people who continue to exist in readers’ minds long after the book closes.

So how do we do this?

Well, it may not seem like the obvious choice, but the setting can be one of the best tools through which to organically reveal truths about your characters. Here are two quick tips on how to use the setting to characterize your cast for readers:

As the gods of our own little universes, we have the power to choose literally everything. But when it comes to the setting, the decision is often a halfhearted one���since the setting is just a backdrop, right? Wrong.

Every character has a history of blissful interludes, toxic run-ins, embarrassing moments, and traumatic episodes. And long after these formative events have been forgotten or buried, their settings will continue to hold significance for the characters involved.

For instance, let’s say that after being out of the romance game for a while, your heroine has agreed to go on a first date, and you need to decide on a setting.

Instead of falling back on a generic location for this scene, brainstorm some possibilities that hold significance for the character. Maybe her date has asked to meet at the same caf�� where her fianc�� once dumped her. Or in the park where she was mugged. Or at the bar where the guy she’s been in love with since tenth grade works as a bouncer.

Any of these settings can work because they’re already emotionally charged for the protagonist.

A first date can be difficult in and of itself; experiencing it in one of these places is going to heighten the character’s emotions and bring back old memories when she’d rather avoid them, ensuring that she won’t be at her best. When it comes to the important scenes in your story, complicate matters for your protagonist and tap into his or her emotions by choosing settings with personal significance.

Get Personal with the Details

Showing rather than telling is the most powerful means of providing insight into the personality of your protagonist and other cast members. Rather than explaining your characters through boring chunks of narrative, hone in on the personal details within a given setting that will tell readers about the people inhabiting it:

I surveyed Rossa’s spotless kitchen. Dishes in their racks���sparkling. Wooden counters���scrubbed to a stone-like smoothness. Rossa herself���hair perfectly arranged, clothes crisp even at this hour, the frivolous fall of lace at her throat. I crossed my arms and couldn’t help wondering, again, how she and Dad could be meant for each other.

Here we have a scene that says loads about its owner. Rossa is meticulous when it comes to tidiness���both for her home and herself. You get the feeling that she values propriety and appearances. And we learn something about the narrator, too: she isn’t so concerned with all of that. She disdains it, in fact, and doesn’t seem to like her Dad’s love interest very much. All of this we’re able to infer from the simple description of a kitchen.

Personal spaces can be quite telling. Make them do more than simply set the scene by zooming in on those details that reveal something about your characters. And for those vital scenes in your story, put your cast members on edge by thoughtfully choosing the settings���ones that add an emotional component or will up the stakes. Resist the temptation to settle for a generic setting and start putting your locations to work for you and your characters.

The post Using Your Setting to Characterize appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 1, 2024

7 Tips to Make Your Antihero Stand Out

When it comes to story heroes, there are many kinds, from reluctant to tortured to tragic. But the one that���s getting a lot of airtime these days is the antihero.

Heroes get the moniker because of the qualities they embody: they���re honorable, courageous, selfless, and good. They���re people of high integrity. These characters make good protagonists because readers value and admire those qualities. We���re eager to walk with them on their journey, and we naturally end up rooting for them.

Antiheroes, though, lack many of the traditionally heroic traits���or they embody the opposite. As such, they really shouldn���t work, because why would we root for people who stand for things we don’t like? But many readers do get sucked into their stories and end up on this unconventional protagonist���s side, wanting what���s best for them. Authors make this happen with a few tried-and-true techniques for writing these characters:

They���re complex, with complete backstoriesThey’re well-rounded characters with a mix of positive and negative traitsThey adhere to a strong moral codeThey struggle with internal conflictBut with all the villain origin stories and other antihero offerings on the market today, we’ve got to move beyond tried-and-true if we want our stories to stand out. So let���s look at 7 additional techniques we can use to make our antiheroes more compelling and memorable.

1. Make Them a Reluctant AntiheroGetting readers to fall in love with an antihero can be tricky if, in the reader���s mind, their undesirable traits and habits outweigh the good. So start these characters out as the good guy.

Walter White (you knew we���d get there eventually, so let���s get right to it) starts out as a barely-getting-by chemistry teacher with a physically disabled son and a baby on the way. And then he���s diagnosed with terminal cancer. We like Walt straight off because he���s an honorable person in a crappy situation with a relatable goal of just wanting to provide for his family. In the beginning, he doesn���t want to resort to making meth. He doesn���t want to become a criminal. He���s just doing what he has to in a desperate situation.

The reluctant antihero works because they don’t start off bad; they start as a protagonist people can relate to, ensuring that readers are fully drawn into the story as they see the hero being pulled to the dark side.

2. Show Their Full Tragic ArcThese stories can start one of two ways: with the protagonist as a fully actualized antihero, or with a character who will become an antihero over time. Each approach has its merits, but the latter highlights the protagonist���s entire journey from start to finish. Readers will often stick with the character because they’re already invested, and by the final page, they understand why the character is who they are.

Estella Miller is the star of Cruella, a young woman who dreams of being a fashion designer and is doing her best to get along in a society where she doesn���t quite fit. Over time, her need to succeed grows, turning her into someone who is controlling and disloyal, someone who will manipulate others and be downright mean to get what she wants. Then she discovers that her mother was murdered by her mentor, and her desire for revenge turns her into the full-blown Cruella we���re all familiar with. As a kid, I never empathized with Cruella, but I do after seeing where she came from and what makes her tick.

3. Make Them SympatheticReader sympathy is often a byproduct of a show-don���t-tell character arc���another benefit of letting the whole arc play out in your story. But even if your character is an antihero from page one, you can still engage reader empathy through the character���s vulnerability or weakness, as we see in the following examples.

Tony Soprano: the ruthless, hardcore mafia boss whose panic attacks land him in therapy, where he must look at himself honestly and analyze his actionsLisbeth Salander, whose history of extreme abuse makes her violent and antisocial nature seem almost acceptableJohn Rambo: the Green Beret war hero who is mistreated and misunderstood and finally pushed past his breaking point by a bigoted small-town sheriffMichael Scott, the neediest, most desperate-for-attention, most annoying office manager ever, who you still can���t help but feel for���Revealing your antihero���s weakness or internal struggle is a great way to get readers empathizing with them, which will encourage them to overlook the habits and traits that would normally turn them off.

4. Make Them Unusual

When it comes to creating unforgettable characters, never underestimate the power of a unique premise. Sometimes, giving an antihero a twist or fresh idea that hasn���t been done before is enough to make them stand out. It���s Sherlock Holmes’ almost-extrasensory powers of deduction. Or Dexter Morgan, a high-functioning sociopath and serial killer who satisfies his compulsions by killing bad people. And who can forget Johnny Depp���s Keith Richard���s-inspired version of the dishonest and egocentric Jack Sparrow?

To make your antihero stand out, give them a twist via an unexpected character trait, quirk, hobby, skill, or job.

5. Give Them Good IntentionsThe most questionable of methods can often be overlooked if the character���s intentions are honorable. I really like Scarlett O���Hara for this one. She���s a despicable person���manipulative, a liar, completely self-serving. She should be universally disliked, but so much of what she does is to save her home. Author Margaret Mitchell is a master of making the setting a character, and readers come to love Tara as much as they love the cast. They don���t want to see it fall into enemy hands and be destroyed. And they recognize that Scarlett���s identity is so wrapped up in her family���s land that if she loses it, she���ll lose herself. Readers almost can���t blame her for doing what she does to save it.

Give your antihero a strong goal and meaningful purpose for doing what they do, and in the reader���s eyes, the end will often justify the means.

6. Establish LimitsWriting an antihero requires us to walk a fine line between remaining authentic to who the character is while still keeping them likable. One way to maintain that balance is to set limits beyond which the character won���t go.

In Cormac McCarthy���s The Road, The Man���s purpose is to protect his son in a brutal post-apocalyptic world. It���s a noble and relatable goal, and he���s an antihero because of the things he must do to keep them both safe. But there are lines he won���t cross that many of the other survivors have already embraced���namely, kidnapping and killing people as a food source. Readers may not like a lot of what The Man does, but his adherence to certain ideals, even when doing so puts his goal in jeopardy, keeps us in his corner.��

7. Keep Readers GuessingLet’s be honest here; it’s a lot of work, trying to make your antihero sympathetic and relatable. So maybe there’s another way. With the right circumstances, it���s possible to write a story that disguises your antihero as something else.

In the first full half of Gone Girl, we think Amy Dunne is innocent, that her husband is the horrible person and she���s his victim. But it turns out she���s as antihero-y as any antihero ever was.

Flip the scenario, and you end up with everyone���s favorite antihero, Severus Snape, whose good qualities were deliberately downplayed to make readers think he was simply a villain. When the curtain���s pulled back, he���s revealed to be one of the most awesome examples of all time.

Antiheroes aren���t new. They���ve been alive and kicking since the time of Shakespeare, Greek mythology, and the Bible. But their recent revival has created a slew of them, and you don���t want yours to get lost in the maelstrom. Use these tips to create a new���dare I say, Snape-worthy?���antihero that will top readers��� lists of favorite and most memorable characters of all time.

The post 7 Tips to Make Your Antihero Stand Out appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

July 30, 2024

Reader Empathy Begins with Compelling Character Emotion

Do you know how many books are on the market today? Neither do I. I can���t count that high. This is awesome for readers, but it creates a problem for authors looking to create a fan base. Not only do we need customers to find our books, we need them to love them���enough to finish them and go on to consume everything else we have to offer.

To make it in this crowded space, we need to attract readers who are obsessed with our work. We want them staying up late and oversleeping because they couldn���t put our book down, texting friends to tell them how awesome it is, and running to the computer when they���re done to see if there are more coming out.

Basically, we want raving fans���customers who read all our stuff and do the word-of-mouth marketing for us. But how do we get this kind of response to our books?

We do it by generating empathy.

When readers start to care about the main character, they���re going to be invested in what happens to him. And they���re going to keep reading to make sure everything turns out okay.

This means we have to get readers feeling as they read. And the best way to do that is by conveying the character���s emotion in a way that evokes emotion in the reader. Let me give you an example from the second edition of The Emotion Thesaurus.

Jason tapped on the door frame. The battle-axe didn���t look up, just kept slashing through numbers on her sales report.

���Um, Mrs. Swanson?��� No response. He shifted his weight, wondering how to proceed. He couldn���t mess this up. He couldn���t miss another of Kristina���s games.

Jason shuffled half a step into her office. ���Um ��� about this weekend? I know your email said I needed to work, but ��� Well, I kind of already have plans������

���Cancel them,��� she said in a tone that was as forgiving as her Sharpie. When he didn���t answer, she looked up.

His gaze dropped to the rug.

In this example, it���s easy to see what the character is feeling without it having to be stated. The body language cues (the tentative tap on the door, his shuffling steps) combined with his speech hesitations and unsettled thoughts convey uncertainty and nervousness. This is an example of emotion that has been shown rather than told, and it works for building character empathy for a few reasons.

It Makes the Reader an Active ParticipantShowing emotion is effective because it pulls the reader in close to what���s happening. When readers are simply told what the character���s feeling (Jason was nervous), they���re not involved; they���re put at a distance, just sitting back and listening to someone tell them what���s going on.

But when the character���s emotions are shown through body language, vocal cues, thoughts, and dialogue, readers are able to infer what���s happening for themselves.

This process of figuring things out is part of what makes reading such a satisfying experience. We don���t want everything explained to us; it���s rewarding to be able to follow the clues and put the pieces together, even if we don���t know that���s what we���re doing. Showing emotion gives readers that opportunity.

It Engages the Reader���s EmotionsEmotions are universal���meaning, whatever your character is feeling, the reader has most likely felt it too. When we���re able to show that emotion in an evocative way, it can evoke a hint of that same feeling for the reader, because they���ve experienced what the character is going through.

Readers who feel a sense of doubt or fear or elation are going to be far more engaged than ones who sit back and watch other people feeling those emotions.

Showing Emotion Creates a Sense of Shared ExperienceWhen readers recognize the character���s emotional state as one they���ve experienced in the past, it creates a sense of shared experience. Readers will connect with the character, even on a subconscious level, because of this thing they have in common. This is a common way for empathy to begin.

When we master the art of showing emotion, readers become active participants in the story, their emotions are engaged, and they feel a sense of kinship with the character. All of this can lead to increased empathy and the reader being invested enough in the character to keep reading. If we can accomplish this in all of our books, it just might result in customers who keep coming back for more.

The post Reader Empathy Begins with Compelling Character Emotion appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

July 25, 2024

What’s Your Character Hiding?

Being able to write realistic, consistent, multi-dimensional characters is vital to gaining reader interest. Doing so first requires we know a lot about who our characters are���you know, the obvious stuff: positive and negative traits, behavioral habits, desires, goals, and the like. But it���s not always the obvious parts of characterization that create the most intrigue. What about the things your character is hiding?

Everyone hides. We hide the goals we know are wrong for us, opinions that may turn others against us, or feelings and desires that make us feel vulnerable���basically anything with the potential for rejection or shame.

The same should be true for our characters. When characters are cagey out of a need to protect themselves from emotional harm, readers understand that. It makes the characters more authentic and can pique your readers��� interest as they try to figure out the secret or worry over what will happen when it comes to light.

7 Things Your Character Is HidingTo add this layer of depth to your characters, you first need to know what���s taboo in their minds���not only what they���re hiding, but why. Here are some common things your character may feel compelled to conceal from others.

1. DesiresDesires are an important part of who your characters are. These desires drive their actions and decisions in the story. While these wants are often transparent, there are situations in which the character may not feel comfortable sharing them.

Maybe she���s secretly pining for her sister���s ex, or she longs for a career forbidden by her parents, or she wants to fight her boss���s unethical behavior but is afraid of losing her job.

Forbidden or dangerous desires can add an element of risk, upping the stakes for the character and making things more interesting for readers.

2. FearsEveryone has fears. Many of those fears are perfectly acceptable, which makes it safe for us to share them. It���s the ones that make us feel weak or lessen us in the eyes of others that we keep in the dark.

Think about uncommon fears, such as being afraid of a certain people group, physical intimacy, or of leaving one���s house.

Unusual fears like these should always come from somewhere���maybe from a wounding event or negative past influencers. Make sure there���s a good reason for whatever your character is afraid of.

3. Negative Past EventsSpeaking of wounding events, we each have defining moments from the past that we���re reluctant to share with others or even acknowledge ourselves.

What���s something that could have happened to your characters that they���ll go to great lengths to keep hidden? What failures or humiliating moments might they alter in their own memories to keep from facing them?

Wounds are formative on many levels, so it���s important to figure out what those are and how they may impact the character.

4. Flaws and InsecuritiesBeing flawed is part of the human experience. There are things about ourselves we don���t want to examine too closely and which we definitely don���t want others to know about.

For characters, these flaws often manifest as insecurities or negative traits (such as being weak-willed, unintelligent, or vain). Whether these weaknesses are real or only perceived, characters will try to downplay them.

But part of their journey to fulfillment includes facing the truth and acknowledging the part their flaws play in holding them back. To write their complete journeys, your need to know what weaknesses they���re keeping under wraps.

5. Unhealthy BehaviorsSometimes characters exhibit behaviors or habits they know aren���t good for them. Maybe these behaviors stem from a wounding event or an unhealthy desire. Maybe they really want to change, but they don���t know how.

Whether it���s a promiscuous lifestyle, a gambling addiction, or a compulsion to self-harm, they���ll expend a lot of energy to keep these behaviors hidden.

Revealing these behaviors to readers, while hiding them from other characters, is a great way to remain true to the human experience while also building reader interest.

6. Uncomfortable Emotions

While it���s healthy to embrace and express a range of emotions, characters are not always comfortable with all the feelings. This may occur with emotions that are tied to a negative event from the past. It may be an emotion that makes the character feel vulnerable or is culturally unacceptable.

The character will want to mask any uncomfortable emotions, often disguising them as something else: embarrassment is replaced with self-deprecation, or fear manifests as anger. This duality of emotion is important because it humanizes characters for readers and adds a layer of authenticity that might otherwise be missing.

7. Opinions and IdeasEveryone wants to be liked. To gain the respect of others, we often go so far as to sacrifice honesty.

If an opinion isn���t popular, your characters may keep it to themselves. If they have good ideas others won���t appreciate, they won���t share them���or they���ll get the ideas out there in a way that allows them to avoid taking ownership.

Peer acceptance is important to everyone; that need, and the secrets that accompany it, is something that every reader will be able to relate to.

***

Deception���whether deliberate or subconscious���is part of the human experience. When your characters hide things from others, they become deeper and more layered and avoid turning into clich��s. They���ll come across as more authentic to readers, who will be able to relate to them. It also can build empathy as readers see the character headed the wrong direction. A lot of good can result from taking the time to discover what your characters are hiding. So put on your Nosy Pants and get to work!

The post What’s Your Character Hiding? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1022 followers