Angela Ackerman's Blog: Writers Helping Writers, page 18

September 26, 2024

7 Tips for Finding Perfect Character Names

How much time do we spend thinking up character names?

Too much.

That name will represent the character we love, so the pressure���s on to get it right. And no one wants to get halfway through a manuscript and realize they have to make a change. Find and replace on that scale, with something that important? No thank you.

Resources abound on the common problems we see with character names (impossible pronunciations, contrived spellings, too many similar-sounding names), so I don���t need to cover that ground. Instead, I���d like to provide some tricks for finding a name that���s perfect for your character.

1. Don���t Reinvent the WheelSometimes, a simple name is best. One that���s invisible to the reader and doesn���t call attention to itself. In this case, don���t go through mental gymnastics to come up with something new when there are thousands of names that already exist. Here are some resources for finding those.

Baby Name BooksEncyclopediasObituaries. Agatha Christie liked these.Your Own Family TreeMaps and Atlases. Paris, Jordan, Brooklyn, Asia���get inspired by names of other places.Graveyards. If it was good enough for Rowling���. This can be helpful if you���re writing a period piece and want to find a popular name, you want to avoid something that���s too common, or you���re looking for inspiration.Name generators. I like , which lets you search up fantasy and medieval names, as well as those based on certain languages.These are helpful for brainstorming real names. But if you���d like a moniker with more gravitas that fits your character and story, keep the following tips in mind.

2. Know the Character���s RoleThe more important a character is to the story, the more memorable or purposeful their name can be. The opposite is true for background characters, because a peripheral character with an interesting or attention-grabbing name could pull the reader���s attention where you don���t want it and make them think there���s more going on back there than there really is. For those characters, consider a more common name, just a first name, or no name at all.

3. Choose Something that CharacterizesThink about what a character���s name could reveal about them. The obvious tells point to a character���s race, religion, gender, or the time they live in. In some cultures, it could identify their profession.

Also, consider what the character does with their name. Do they shorten it or use it in its entirety in the most pretentious way (Charles Emerson Winchester the Third, anyone)? Do they use a nickname that says something about their preferences, ideals, or attitude? If the character came up with it themselves, it often will say something about them.

4. Explore the Root Meaning

One way to subtly characterize is to choose a name with deeper meaning.

Beorn, the shape-shifting warrior in The Hobbit, comes from an Anglo-Saxon word meaning warrior/chieftain and an Old Norse word for bear.Kreacher���sniveling house elf to the Regulus family in Harry Potter���comes from the German word kriecher: to creep, crawl, grovel, cringe, or fawn upon.Shrek is Yiddish for fright.And then there���s Percy Wetmore, The Green Mile���s bullying, cowardly antagonist who���s such a wuss he ends up peeing his pants in fear.is a great tool that provides the etymology and history of many names. Even if readers don’t know the underlying meaning, a name with significance will often work because of the way it sounds or the connotations it evokes. And that brings us to the next tip:

5. Utilize Sound DevicesDid you know that explosive consonants have a jarring and unsettling effect to the hearer? These sounds (p, b, d, g, k, ch-, sh-) can work well for a villain���s name���Gordon Gekko, Krampus, Count Dracula, and the like. On the flip side, harmonious/soft consonants (l, m, n, r, th, wh, soft f, soft v) may be good for peaceful or nurturing characters, such as Luna Lovegood or Melanie Wilkes (Gone with the Wind). There are obvious exceptions, but the sound of a name is a good place to start when you���re trying to figure out the right handle for a character.

6. Evoke a Desired ResponseTo build on the last point, devise a memorable name by making the whole thing alliterative, musical, lilting, quirky, unnerving, or unsettling���whatever you���re going for. Inigo Montoya, Sam Spade, Boo Radley, Scheherazade, and Ponyboy Curtis are good examples. What do you want your character���s name to bring to the reader���s mind? Create an overall sound that fits.

7. Tie it to the Story���s ThemeWhat message do you want to convey, and how does the character relate to it? One of the themes of Watership Down circles leadership. Hazel must lead his band of reluctant rabbits to a new home, but he has no special skills; he���s not fast like Dandelion or strong like Bigwig. He���s just a regular guy. The rabbits in this story are all named after plants, so you���d expect the leader to have a grand, inspiring name, but Hazel, in lupine, simply means ���tree.��� His name reflects the story���s thematic message, that leadership doesn���t require flash and charisma; it often just means being willing to do what must be done.

There are so many tips for coming up with the perfect name for a character. But as always, the name needs to fit both them and the story. If readers are pulled out of the narrative because they���re enamored with (or confused by) them, we���ve led them astray. So have fun digging into those names, but remember that they���re just one part of the bigger picture.

The post appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 24, 2024

Five Pitfalls to Avoid When Developing Your Antagonist

By Savannah Cordova

It���s been said that every good story needs a villain. While that villain doesn���t have to be another character ��� it can be something more abstract, like a supernatural force or even fate itself ��� this ���person-to-person��� conflict is often what���s most compelling for readers.

But just because you���ve landed on this form of conflict for your story, doesn���t mean everything will naturally fall into place; far from it! An antagonist in this sense must be just as carefully developed as your protagonist, and it���s crucial to avoid the classic traps that people fall into when creating villains.

Here are five pitfalls to avoid when developing your antagonist, with illustrative examples to help you along the way.

1. Making Them Completely UnsympatheticYou���ve probably heard this one, but it bears repeating: if your villain has no redeeming qualities whatsoever, their journey ��� and their relationship to the protagonist ��� won���t be terribly exciting. Readers might be glad to see them get their just desserts, but they���re unlikely to get invested, and won���t remember much from your story beyond its generic ���good vs evil��� arc.

This doesn���t mean readers must have equal amounts of sympathy for your hero and your villain; it does, however, mean that the latter needs some grounding, realistic traits and goals. Think about their core motivations in your story. Why are they opposed to your protagonist in the first place, and how does that tie into their personality?

A low-stakes example: say you���ve established that your protagonist is a schoolteacher, and their nemesis is a grouchy school principal who thwarts the teacher���s ideas and initiatives at every turn��� but why? Maybe the principal has been burned by bureaucracy and is disillusioned with the system; maybe they���re trying to prevent the teacher from getting promoted and leaving the school; maybe they���re jealous of the teacher���s good ideas and work ethic, etc.

Remember, these motivations don���t have to be flattering, but they do have to have to be comprehensible. Even if the reader wouldn���t take the same actions as your antagonist, they should be able to grasp their reasons for doing so ��� basically, a good antagonist doesn���t require total reader empathy, but they do require some sympathy and understanding.

2. Failing to Consider Their BackstoryIn conjunction with that first point, don���t just stop at your antagonist���s immediate motivations re: your protagonist! If you really want to develop a worthy opponent, you must consider their entire backstory: their childhood and formative experiences, their turn to the ���dark side��� (whatever that means in your story), and other aspects of their life beyond the page.

Indeed, unlike the sympathetic elements to include in your story, your antagonist���s backstory may not be fully revealed to readers. If you���re familiar with the ���iceberg theory��� of fiction, that���s the technique to employ here; the details you divulge should only be the tip of an ���iceberg��� of backstory. The rest remains beneath the surface, largely unseen, but adding meaningful subtext to the details you do mention ��� and ready to be deployed in future books if needed.

Think about one of the most famous villains of all time, Voldemort from Harry Potter. One reason why he���s so effective as a character is because we know just enough about him to see him as a legitimate threat��� but plenty about him also remains mysterious and frightening.

Over the course of the books, we learn more about Voldemort���s family trauma, orphaned childhood, and fundamental misconceptions about things like love, power, and immortality. Through this process, we see how his backstory has subtly informed his character all along. And when he and Harry have their final confrontation in Book 7, we���re invested in the outcome partly because we know both characters intimately now, not just Harry alone.

3. Barely Letting Them Interact with Your ProtagonistSpeaking of final confrontations, another surprisingly common mistake with antagonists is to not ever let them encounter the protagonist until the very end ��� if they interact at all!

Some authors might think this creates a sense of mystery and narrative suspense. But while this tactic might work well for a short story, it starts to feel tedious and flat-out strange in a novel. A few times I���ve gotten well past the halfway point in a book and thought: ���Okay, but when are these two going to meet?���

One popular novel I read a few years ago (I won���t mention the title) was particularly guilty of this, with chapters that alternated POVs between the protagonist and the antagonist. The villain kept trying to meddle with the hero in roundabout ways, but the hero didn���t really understand what was going on, so it was frustrating to keep going back and forth. The two never metuntil a climactic battle at the end of the book��� at which point the story had already lost a lot of steam.

So don���t take this approach to your own villain���s arc. Instead, try doing the opposite ��� that is, intertwining your protagonist and antagonist���s paths as early as possible. Another novel from a few years ago (which I will name), Vicious by V.E. Schwab, does a brilliant job of this: the two main characters, Victor and Eli, are college roommates and friends before they turn enemies, and their established relationship and history makes their dynamic all the richer.

4. Having Them Do Stereotypical ���Villainous��� Things

This is another one that seems obvious to avoid, but comes up surprisingly often! It���s unfortunately true that even once you���ve rounded out your antagonist with backstory and strong motivations, you can still find them slipping into stereotypical actions. These include: delivering evil monologues at the protagonist, laughing the quintessential ���mua-ha-ha��� laugh, shooting a man in Reno just to watch him die, etc.

You may be more susceptible to this issue if you write fantasy, horror, or any sort of ���epic��� fiction in which the hero and villain have an archetypical relationship. But just because your genre can occasionally get trope-y, doesn���t mean you���re doomed! Really, the best way to combat this pitfall is just to stay aware of it. Try to remain meticulous as you write your villain���s scenes ��� and when the time comes to edit, do so with fresh eyes and a staunch intolerance for clich��s.

Alternatively, depending on what kind of fiction you���re writing, you could try subverting or lampshading certain stereotypes��� but you need to have a lot of confidence in your satire in order for this to land! As a result, I���d generally advise to simply steer clear.

5. Creating Multiple Antagonists Who Are Very SimilarFinally, this piece of advice is for those writing a series, particularly if you have the same protagonist from book to book (which, to be fair, not all series have).

Basically, if you remove or kill off a villain in one book, don���t bring back a nearly identical villain in the sequel ��� not just in terms of looks (though best to avoid that as well!), but in terms of key motivations and personality. It might feel natural to have similar antagonists ��� especially if your protagonist is defined by a worldview that their enemies always oppose ��� but remember that the majority of a villain���s character details should be unique to them.

This is what makes villains in media like the Batman comics so vivid and memorable: though Batman���s enemies are united in their criminality, they all have different motives for their crimes, different modi operandi, and certainly different personalities (just think about the Joker vs the Penguin, for example). If you happen to be writing a series of books or even stories, you should strive for the same degree of differentiation.

With that, I do wish you the best of luck in creating your own iconic antagonists. If you avoid these all-too-common pitfalls, you���ll be well on your way to character dynamic success!

Savannah Cordova is a writer with Reedsy, a marketplace that connects authors and publishers with the world���s best editors, designers, and marketers. In her spare time, Savannah enjoys reading contemporary fiction and writing short stories. You can read more of her professional work on Litreactor and the Reedsy blog.

The post Five Pitfalls to Avoid When Developing Your Antagonist appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 21, 2024

Introducing���the Character Secret Thesaurus

Every character has secrets they don���t want other people to know. Some are benign (something they like that others don���t, what they really think about a co-worker, that box of Thin Mints they polished off last night). They���re interesting, but whether these secrets come to light or not, they won���t impact their life.

But all secrets aren���t created equal. Some are powerful enough to threaten what the character holds dear: their reputation, closest relationships, the ability to achieve their dreams, and even their values and identity. Whether the threat is real or only perceived, the character will go to great lengths to keep the secret hidden���sometimes causing more harm trying to bury it than if it was discovered. In many cases, the secret will need to come out, or the character will at least have to see it with clarity and deal with it on a personal level to find peace.

It’s these formative, emotionally charged, and potentially costly secrets that can wreak havoc in a character���s life, changing who they are and determining the course of their story. They should figure, on some level, into every story, which is why Angela and I decided to create The Character Secret Thesaurus.

Whatever your character is hiding, there are certain things you���ll need to know as the author so you can write it convincingly. Here���s a breakdown of what we���ll cover for each secret in this thesaurus.

A Variety of Brainstorming Options. There are sooo many secrets a character could have. We’ve narrowed the list for you and focused on the ones we think could be most helpful from a variety of categories, including family and relationship secrets, past criminal acts, health issues, hidden identity, dark secrets, and more.

Fears Driving the Secret. We hide things because we���re afraid���afraid of being punished, people thinking badly of us, losing control or autonomy, and a host of other things. But while the secret may generate problems for your character, it���s only a symptom of a deeper root cause. Figure out what they fear the most, and you���ll know what���s driving their behavior in the story.

How the Secret Limits Them. Every secret will require deception to keep others from discerning the truth���even when it���s being kept for a good reason. Characters will be dishonest with their words and their actions. They���ll lie to themselves to keep from seeing the whole picture about their secret or the harm it���s causing. These are the consequences of keeping the truth hidden, and when readers see them unfolding, they���ll empathize with the character, wanting better for them. If the character will have to eventually disclose their secret to achieve fulfillment, recognizing these limitations will also help them get there.

Behaviors That Will Help Hide the Secret. How will you character keep the truth under wraps? What behaviors will they practice? What habits will they develop? How will they alter their own way of thinking so it���s easier to keep their secret? Some of this will be deliberate, and some of it will occur on the subconscious level. All of it is necessary for you to know so you can show (not tell) the character���s drive to protect the secret and why it���s so important to them.

Tendencies That Will Raise Suspicions. The longer a secret goes on, the more deception a character must engage in, and the harder it will be to uphold the facade. Despite their best efforts, glimpses of the truth will be revealed through things they say, looks they give, and activities or people they shy away from. These moments can establish the progression toward an inevitable reveal. At the very least, they���ll up the stakes and generate conflict that will make the character���s job more difficult.

Situations That Will Make the Secret Harder to Keep. If the story requires the secret to be revealed, you���ll need to create opportunities for that to happen. These scenarios can also help the character realize, bit by bit, that a secret isn���t worth keeping and needs to be let go.

Results of the Secret Going Public. If the character desperately needs to keep something private, what happens if they fail? High stakes are important for readers because they reveal why the character is working so hard to hide the truth. But the revelation of a secret can have positive results, too, becoming a blessing in disguise. We���ll explore the good and the bad so you���ll know all the options for the secret your character is keeping.

Bottom line: secrets are universal. A character who has an important, high-stakes secret will become more authentic to readers, building empathy and relatability. Their attempts to hide the truth will play into both character arc and story development, making this an important storytelling element. Our hope for this thesaurus is that it will provide insight and guidance for incorporating secrets into your story on many levels.

Look for the first entry next Saturday, the 28th!The post Introducing���the Character Secret Thesaurus appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 18, 2024

Phenomenal First Pages Contest

Hey, wonderful

writerly people!

It���s time for Phenomenal First Pages, our monthly critique contest. So, if you need a bit of help with your first page, today’s the day to enter for a chance to win professional feedback!

Entering is easy. All you need to do is leave your contact information on this entry form (or click the graphic below). If you are a winner, we’ll notify you and explain how to send us your first page.

Contest DetailsThis is a 24-hour contest, so enter ASAP.Make sure your contact information on the

entry form

is correct. Three winners will be drawn. We will email you if you win and let you know how to submit your first page. Please have your first page ready in case your name is selected. Format it with 1-inch margins, double-spaced, and 12pt Times New Roman font. All genres are welcome except erotica.Sign Up for Notifications!

Contest DetailsThis is a 24-hour contest, so enter ASAP.Make sure your contact information on the

entry form

is correct. Three winners will be drawn. We will email you if you win and let you know how to submit your first page. Please have your first page ready in case your name is selected. Format it with 1-inch margins, double-spaced, and 12pt Times New Roman font. All genres are welcome except erotica.Sign Up for Notifications!If you���d like to be notified about our monthly Phenomenal First Pages contest, subscribe to blog notifications in this sidebar.

Good luck, everyone. We can’t wait to see who wins!

PS: To amp up your first page, grab our First Pages checklist from One Stop for Writers. For more help with story opening elements, visit this Mother Lode of First Page Resources.

The post Phenomenal First Pages Contest appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 17, 2024

Should Your Novel Have a Prologue?

Every word counts in a story and first impressions matter. Traditionally, a prologue is an introductory chapter that sets the scene, tone and genre of your novel. But should you write one? The million-dollar question! Believe it or not, using a prologue can be quite controversial in the social media age.

So, let’s put prologues under the microscope, so you can make an informed choice on whether YOU should use one … let’s go!

What Is A Prologue?Put simply, a prologue is an introductory chapter that lays the groundwork of what’s to come. Their purpose is to hook the reader and make them want to turn the pages. Prologues are usually shorter than the average chapter, but they don’t have to be. Prologues can be controversial because both writers and readers can have strong feelings about whether they are necessary … or not.

You may have seen online discussions in which authors say they believe prologues provide important context and intrigue. Others might reject prologues, saying they can be too cryptic. You may even have heard that readers claim to skip prologues altogether.

So, with all this in mind, let’s explore the pros and cons of writing a prologue. Ready? Let’s go!

Prologue PROsi) Can be important for set up

Prologues can be powerful tools in setting the stage for your story. Early foreshadowing prepares readers for what lies ahead without revealing too much. Ultimately, it’s about creating a sense of anticipation.

ii) Can be important for backstory

In setting the stage for your story, a prologue can allow authors to provide readers with crucial backstory. This may be character or storyworld-related … or both.

iii) Creating Suspense or Intrigue

A good prologue can help hook readers from the very first line. By introducing an unresolved conflict or a puzzling scenario, you create suspense right away. This means good prologues can raise questions without offering immediate solutions.

Prologue CONsiv) Can be confusing

Prologues can sometimes overwhelm readers with excessive information. This is known as ‘info dumping’ and should be avoided at all costs. This is because too much upfront about the characters or storyworld can feel frustrating for the reader.

v) Can disrupt the flow of the story

Narrative flow in a story is very important … and starts with the prologue! If the beginning is too slow or overly complex, readers might become impatient to get to the main plot. They may even skip the beginning altogether. This is because a prologue can sometimes feel like a detour.

vi) Giving away too much too soon

Prologues must not give away too much, too soon. Readers may feel they already know what will happen, diminishing their motivation to keep turning pages. Striking a balance between intrigue and clarity is essential.

So, Should You Write A Prologue?When contemplating whether to write a prologue, consider …

The Genre and Style of Your Novel.��Some genres and styles like historical fiction or fantasy are enriched by prologues. Action thrillers often don’t need one. Weigh it up.Relevance and Impact.��Too much detail can sidetrack – rather than support – your story. Make sure your prologue ADDS to the reading experience, rather than detract from it.Your Personal Writing Style and Preferences.��Be honest with yourself about prologues: do you really need one? Think about what resonates with you and your target reader. Trust your instincts.Last Points

The Genre and Style of Your Novel.��Some genres and styles like historical fiction or fantasy are enriched by prologues. Action thrillers often don’t need one. Weigh it up.Relevance and Impact.��Too much detail can sidetrack – rather than support – your story. Make sure your prologue ADDS to the reading experience, rather than detract from it.Your Personal Writing Style and Preferences.��Be honest with yourself about prologues: do you really need one? Think about what resonates with you and your target reader. Trust your instincts.Last PointsUltimately, you need to decide what will serve your story best … you’re the writer, after all! Weighing up the pros and cons will help you make an informed choice on whether your novel needs a prologue or not.

Good Luck!The post Should Your Novel Have a Prologue? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 12, 2024

The Ultimate Guide for Giving and Receiving Feedback

Years ago I joined the award-winning site, The Critique Circle, where I learned to hone my writing skills and develop the thick skin needed to take criticism and rejection. In addition to writing well beyond a thousand critiques, I became a moderator for the site, and with members in the thousands, I mediated situations that cropped up between writers who either struggled to give an appropriate critique, or to accept one.

This experience taught me the value of peer feedback. Learning how to give and take a critique is one of the best ways to develop your writing skills. Critiquing isn’t a walk in the park, however. It���s very easy to let one���s emotions get in the way and damage relationships. For this to work, a person must respect the other���s role, value the time and energy writing and critiquing takes, and follow through without letting emotions overrun good judgment or manners. Here are ���best practices��� writers should observe in each stage of the Critique Process.

When Asking for a CritiqueIf you are lucky enough to find someone willing to give feedback, it is your job to make your work presentable. Here���s how:

Be honest about the stage the work is in. If this is a first draft, say so. Readers need to understand what they are looking at to offer you the best advice on how to proceed.Respect their time. Don���t be unreasonable regarding turnaround time. If you are on a deadline, make sure that is understood before you send your work. If you like, ask for the critter���s best guess for having it back to you. Contact them (politely) to ask how it is going only after this time has passed.Always send clean copy. First draft or last, make sure you have fixed typos and punctuation, and hopefully taken a stab at grammar as well. If your work is full of mistakes and your manuscript reads poorly, it becomes distracting and takes away from the critter���s ability to offer insight and advice on the story itself.Ask questions or voice concerns only at the END of the writing sample. This allows you to hone in on areas you���re worried about, but by placing questions at the end, you ensure the person reads the submission ���clean��� and without bias. Otherwise they will be looking for specific things as they read, and may miss the forest for the trees.When Giving a CritiqueIt is the critique partner���s job to pay the submission the attention it deserves. Some important points to remember:

Focus on the writing, not the writer. No matter what shape a story is in or how green the writer may be, a critter���s job is to offer feedback on the writing itself, not a writer���s developing skills (unless you are praising them, of course).Offer honesty, but be diplomatic. Fluffy Bunny praise doesn’t help, so don���t get sucked into the ���but I don���t want to hurt their feelings��� mindset. Your honest opinion is what the writer needs to improve the story, so if you notice something, say so. However, there is a difference between saying ���This heroine is coming across a bit clich��,��� and saying, ���This character sucks, I hate her���what a total clich��.���Be constructive, not destructive. When offering feedback, voice your feelings in a constructive way. To continue with the clich�� character example, explain what is making her come across clich��, and offer ideas on how to fix this by suggesting the author get to know them on a deeper level and think about how different traits, skills and flaws will help make her unique. Give examples if that will help. Bashing the author���s character helps no one.Be respectful. Regardless of where the writer may be on the path to publication, they have chosen to share their work with you, and this will make them feel vulnerable. Honor this by treating them and their work in a respectful way.Praise the good along with pointing out the bad. Sometimes we get so caught up in pointing out what needs fixing we forget to highlight what we enjoyed. If there���s something amazing about the work, say so. Even if the story is not your favorite, try to point out something positive, even if it is a simple description or dialogue snippet. The positives are what help writers keep going even when there is still a lot of work to do.Offer encouragement. Part of our job when critiquing is to offer encouragement. We want to build people up so they work harder to succeed, not tear them down and erode their confidence. End any critique with some words of support and friendly encouragement so it reminds them that writing is a process and we���re all in this together.Return the critique in a timely manner. If it has not been agreed upon before you receive a submission, give the writer a ballpark timeline to have the critique returned to them and then stick to it. If you need an extension, don���t wait for them to ask where the critique is���be proactive and explain your circumstances.When Receiving a CritiqueA critique waiting in our inbox brings about both excitement and dread. This is the final phase, with important steps to follow.

Before opening the critique, let the critter know you received it, and that you are looking forward to reading it as soon as you have a chance. This lets them know that it didn’t get lost in cyberspace, and that you have not yet read it, which gives you some time to process the critique without them wondering why you haven���t said anything about it to them.Before you read the critique, remind yourself that the reason you asked for feedback was to make the story stronger. Set the expectation that you will have work to do, and ultimately the story benefits. Steel your emotions for what is ahead.Read through the critique once. Try your best to not let anger, disappointment or even excitement cloud your read. Then, set it aside and turn your attention to something else. Use this time to go through any hurt feelings this critique caused, and deal with any emotional responses (self-doubt, frustration, even elation). Good or bad, you need to clear emotion from the picture to be able to best utilize this feedback, even if your gut instinct is to disagree with it.When you are ready, go through the critique again, this time, free of emotion. Look at each suggestion objectively and make notes to yourself. If there are suggestions that make you angry or defensive, pay special attention. Often when a comment hits close to home it indicates that something requires more thought. Challenge yourself to see the situation or scene as they did. Do you understand how they arrived at a specific conclusion? Is information missing that would help them view the situation/scene as you intended? This may lead you to realize something needs strengthening. Or, through the act of poking and prodding, you reaffirm your belief that it works as is, and you can dismiss this suggestion. (However, pay special attention when multiple partners highlight the same issue���even if you believe it is good enough, chances are strengthening is needed.)**Respect the Critique Partner���s time and effort. This person likely just spent several hours working on your submission, and regardless if you agree with the feedback or not, you should send a follow up email thanking them for the critique, highlighting how it gave you better insight into you story and characters. If you have questions about the feedback, ask! This is your opportunity for more helpful discussion and ideas on how to make your book better. Do not get angry. Let me repeat that: do NOT get angry. Take the high road, even if you found nothing helpful. Show appreciation for their time, and in the future, find another partner.

Before opening the critique, let the critter know you received it, and that you are looking forward to reading it as soon as you have a chance. This lets them know that it didn’t get lost in cyberspace, and that you have not yet read it, which gives you some time to process the critique without them wondering why you haven���t said anything about it to them.Before you read the critique, remind yourself that the reason you asked for feedback was to make the story stronger. Set the expectation that you will have work to do, and ultimately the story benefits. Steel your emotions for what is ahead.Read through the critique once. Try your best to not let anger, disappointment or even excitement cloud your read. Then, set it aside and turn your attention to something else. Use this time to go through any hurt feelings this critique caused, and deal with any emotional responses (self-doubt, frustration, even elation). Good or bad, you need to clear emotion from the picture to be able to best utilize this feedback, even if your gut instinct is to disagree with it.When you are ready, go through the critique again, this time, free of emotion. Look at each suggestion objectively and make notes to yourself. If there are suggestions that make you angry or defensive, pay special attention. Often when a comment hits close to home it indicates that something requires more thought. Challenge yourself to see the situation or scene as they did. Do you understand how they arrived at a specific conclusion? Is information missing that would help them view the situation/scene as you intended? This may lead you to realize something needs strengthening. Or, through the act of poking and prodding, you reaffirm your belief that it works as is, and you can dismiss this suggestion. (However, pay special attention when multiple partners highlight the same issue���even if you believe it is good enough, chances are strengthening is needed.)**Respect the Critique Partner���s time and effort. This person likely just spent several hours working on your submission, and regardless if you agree with the feedback or not, you should send a follow up email thanking them for the critique, highlighting how it gave you better insight into you story and characters. If you have questions about the feedback, ask! This is your opportunity for more helpful discussion and ideas on how to make your book better. Do not get angry. Let me repeat that: do NOT get angry. Take the high road, even if you found nothing helpful. Show appreciation for their time, and in the future, find another partner.**This last point is very important to nurture a critique relationship.

This person chose to help you, taking time away from their own writing. As someone who often spends hours on a critique, there is nothing more frustrating to me than when a writer does not acknowledge my work. I���m not looking for flowery pats on the head, simply to know the feedback was helpful in some form. Anyone who has given their time is worthy of your appreciation, regardless of whether you agree with their suggestions or not. Be gracious when feedback rolls in.

Consider Offering Feedback in ReturnCritiquing is about give and take, so if someone has kindly given time to help you, offering to look at something in return is the right thing to do.

Do you have any tips to add? Have you found critiquing helpful, or do you avoid it like the dentist’s chair?

The post The Ultimate Guide for Giving and Receiving Feedback appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 10, 2024

How to Strengthen Our Story with Tropes

Every genre and medium of storytelling uses tropes���common themes or story devices. However, the frequency of certain storytelling ideas, such as ���the chosen one,��� makes them so common that readers get sick of them, and every type of trope can seem clich�� or predictable.

Yet tropes are so common that we can���t avoid using them, so it���s better if we can learn how to benefit from them. How can we avoid the problems of tropes and instead use them to help strengthen our story?

Wait, Why Can���t We Just Avoid Tropes?Think of story tropes as a storytelling pattern. Some patterns are big and can encompass the entire story (coming of age), and some patterns are smaller and play out over a scene or two (a double cross).

These storytelling patterns, or tropes, can focus on:

characters (hero���s journey, unlikely allies, unreliable narrator, reluctant hero, etc.)settings (going into a dark basement, vaguely European medieval surroundings, etc.)plot elements (road trip, love triangle, blackmail, trapped in an elevator, etc.)and so on���Any storytelling idea that���s been used more than once becomes part of a pattern, from ���secret admirer��� to ���cellphone battery is dead.��� Virtually every idea, twist, obstacle, etc. falls into a pattern, which means it���s part of a trope.

At this point, even the many ways that authors attempt to subvert a trope have themselves become tropes. Think of a ���damsel in distress��� trope where the damsel isn���t really in danger at all.

Countless numbers of tropes exist, to the point that a whole website is dedicated to them. In other words, tropes are unavoidable.

How Can We Avoid the Weaknesses of Tropes?The pattern aspect of tropes is part of what makes a trope a trope. Audiences can fill in the details of a trope without the story having to spell everything out because they recognize the pattern.

Not surprisingly, that pattern recognition can also create the sense of predictability, clich��, and other weaknesses. However, the worst negative effects of tropes occur when we rely on them to carry the work of the story.

Taking some of the bullet points above, here���s what it means to rely on tropes to carry the story:

For characters, we set up an ���unlikely allies��� trope, but we don���t develop why these characters are working together despite the unlikeliness.For setting, we set up a ���vaguely European medieval surroundings��� trope, but we don���t develop any unique storytelling or worldbuilding details.For plot, we set up a ���blackmail��� trope, but we don���t develop the stakes and motivations of the parties involved.In all those cases, the tropes would weaken the story, regardless of the strength of our other story elements, because we���d be relying on the trope formula to do the work. Our lazy writing would expect readers to recognize the trope to the point that we merely kick off the pattern and wait for the formula to do the rest. The story itself is just going through the motions.

How Can Tropes Strengthen Our Story?

Given that inherent pattern recognition and predictability, how can we possibly make tropes strengthen our story?

Tropes and their patterns tap into universal experiences and emotions. Readers recognize and are familiar with the patterns of those experiences and emotions from other stories they���ve been exposed to, even if they���ve never come across them in real life. With that common background, tropes can help readers instantly grasp complex relationships, emotional flips, and storytelling turns.

So while tropes can be shortcuts to lazy writing, their patterns and expectations can also be shortcuts to relatability and understanding for readers. As long as we���re then building on those shortcuts rather than expecting them to do all the work, our story will be stronger. In other words, rather than relying on tropes to the extent of shortchanging unique details or character/story development, we can use tropes to improve readers��� connection and provide opportunities for deeper development.

Example: How Tropes Can Strengthen Our StoryLet���s say we want readers to feel more connected to a minor character. Here���s one way we can use tropes to shortcut a starting point for the character���s development (which we then build on) and strengthen the character���s connection to readers:

Recognize what tropes/patterns the character represents: The character is an intelligent precocious child, and thus readers will expect a know-it-all who���s always a step ahead of everyone else.Lean into the trope in a way that adds relatability: Make the child more relatable by showing them as an outsider or dismissed in some respects.Recognize the trope���s expectations (and common subversions): Readers will believe that when cornered by the bad guy, the child will come out on top.Subvert the trope in a way that adds opportunities for depth: Instead, the child doesn���t realize the bad guy is manipulating them, because���they are still a child. (Note: Sometimes this step isn���t even on the page because the opportunity is what���s important, not the subversion.)Use the opportunity to add character and/or story development: In the reveal of the child being manipulated instead, use the opportunity to deepen their character development, such as by exploring their feelings of outsider-ness or being dismissed, or maybe their precociousness is a result of feeling like they���re not allowed to make mistakes, and this was a big mistake.In this example, between the child being a victim of the bad guy���s manipulation and deepening their character development on the page, readers will feel doubly sorry for them and thus more emotionally connected to them. As a result, the story will feel deeper and stronger.

Focus on the Opportunity for More, Not the SubversionThere are plenty of advice articles out there about how to twist or subvert a trope:

Change the contextGender/role reversalLayer tropes to come up with something unique, etc.That advice can be great and good to know, and in fact, I���ve written one of those posts. But like mentioned above, many subversions have now become new tropes.

So if we can���t avoid using tropes, and if there���s a limit to how much we can subvert tropes, how can we make them benefit our story? Strengthening our story with ��� or despite ��� tropes is less about the specifics of subverting them and more about how we can take something potentially clich�� and use it to add depth and development to our story.

We can use the shortcuts that tropes provide to give us a quick starting point to build on for more depth in our story. We can use the shorthand of trope relatability to give us room to focus on development beyond or outside of the trope.

In other words, rather than spending our time trying to think of a never-before-thought-of twist for our story���s tropes, we may be better off to accept that tropes aren���t bad���but they are just a starting point. If we instead spend our time using our story���s tropes as a launchpad for adding uniqueness and depth, our story will be stronger. *smile*

Have you struggled to understand tropes before or been stumped for how to twist the tropes in your story? Does this post help you see how embracing them as shortcuts might allow us to add more depth in other ways? Do you have any questions about tropes or their weakness and how to use them?

Check out the Character Type and Trope Thesaurus.

Check out the Character Type and Trope Thesaurus. Use this resource to familiarize yourself with the commonalities for a certain kind of character while also exploring ways to elevate them and make them memorable, more interesting, and perfectly suited for the story you want to tell.

The post How to Strengthen Our Story with Tropes appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 5, 2024

Authors Are Assets, Not Competition

Most industries are competitive. Athletes go head-to-head for the medal or trophy. Car companies vie for market share as do grocery stores, restaurants, and delivery services. Reality TV show contestants duke it out for prize money, prestige, and in some cases (ugh) roses. And our favorite retail Godzilla, Amazon? They compete with everybody.

Know who isn���t your competition? Authors.

Sure, on the surface, it appears a competition is taking place. After all, look at the sea of books on the market, the sky-high submission piles. Think about how we need to list comparable titles when we pitch our work to agents and how past book sales and current platform numbers carry weight acquisitions decides which author will receive a contract offer.

Is it true that agents only take on certain clients and publishers only publish certain books? Yes. But the ���I���m competing against other authors��� idea is a sacred cow leftover from a time when keeping authors divided suited a publishing monopoly (that has thankfully been broken).

Other Authors Aren���t Competition, They���re ASSETS.Here���s Why.Of the bazillion books out there, only a small fraction are ones your exact audience may be interested in.

So, skip any hand-wringing over how flooded the market is — it doesn���t matter. You only need to consider books like yours. And even then, far from being your competition, these books and the authors attached to them can HELP YOU SELL MORE BOOKS. Which brings us to���

2. Your goal is to find your audience. Other authors are a gateway to them.

What now, Batman? Yes, that���s right���your so-called competition has been there, done that and has the t-shirt. They���ve found their readers. In fact, every day they reach more. So, if you do your research and find authors who write books a lot like yours, their readers can become your readers.

In today���s world, authors have online platforms to reach readers no matter where they live, giving you a starting point for finding and connecting with your potential audience. Pay attention to where comparable authors spend their time and you���ll find potential readers. It might be a Facebook group, Instagram, special interest forums, blogs, etc.��� Wherever you see authors who write similar books to you spend their time with readers, this is also a good place for you. Start spending time getting to know people in this space.

Don���t jab promotion at people, just join the conversation, enjoy common ground, and build relationships. If this truly is your audience, there will be topics that tie into your books that will be a subject of conversation and because that���s what you write about and are interested in, you���ll have lots to contribute. Eventually it will come out you ALSO write books about X and sooner or later, folks will check you out. And hey, while we���re talking about how established authors in our niche can help us���

3. Each author is a megaphone to their audience, meaning marketing collaborations with certain authors can help you build your readership more quickly.

When you research other authors to find ones in your niche, read their novels. Is the genre, style, and content a match to yours? Is the book well-written? Can you see yourself recommending this book to people?

If the answer is yes, this author may be someone you wish to collaborate with. If your values align, cross promotion will be a win-win. They encourage their readers to check you out and you do the same for them and you both gain new readers. So, find a good author match and think how you can help THEM sell books and gain visibility.

But wait���that doesn���t sound right. Shouldn���t I be trying to sell my own books, not someone else���s?

Glad you asked, because this ties into a truth we all have to bend our heads around:

4. No matter how fast you write, readers read faster.

One dangerous mistake we can make with our readers is to only think about US, not THEM. It���s ALWAYS about them, which means we need to take care of our audience even after they���ve finished reading all our books.

It takes time to release the next book, and in the meantime, our readers need good books to read. If we do nothing to stay in touch, they might forget about us and the next book, but if we make it a priority to give them more of what they love, we stay on their radar. Recommending books we know our readers will love shows we want them to have a great reading experience over and over again, whether it���s our book or not.

So rather than fearing losing our readers to someone else, we should encourage readers to seek out specific authors. Not only does this encourage reader loyalty, it���s also a great way to gain new readers ourselves. How? Because other comparable authors are in the same boat, and they will be looking to recommend books to their readers, too. Reciprocity is something that���s hardwired into us, so if they see us openly pushing people to their books, they will want to do the same in return. This brings us to a final point:

5. Other authors have a wealth of knowledge we may need.

There���s a lot to publishing and marketing well, and we���re all constantly running into new situations that exposes a gap in our knowledge. Maybe we���ve never tried for a Bookbub and so don���t know the tips and tricks. Or we���re just starting out with newsletters or Amazon ads and have no idea how to do either right. What���s better in these cases ��� spending a bunch of time and money on research, courses, and trial and error, or talking to another author who is successful in that space and asking them to point us to the right information?

And just as others can use their experiences to help us, we can do the same for them. A rising tide lifts all boats!

Honestly, this is just the tip of the ice cream scoop as far as why authors are assets, so I urge you to think about your own genre and who fits your niche. Reach out to your not-competition. Consider ways you can help them, and how you can collaborate to gain bigger readerships!

What was the best advice another writer shared with you?The post Authors Are Assets, Not Competition appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

September 3, 2024

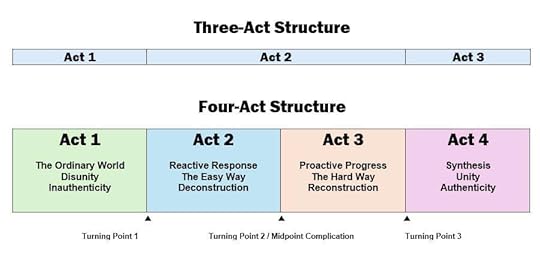

The Missing Link in Three-Act Structure

In any discussion of story structure, the three-act model inevitably dominates the conversation. Even as plotting methods such as Save the Cat, the Hero���s Journey, and the Snowflake Method gain popularity, the classic beginning-middle-end form reaching back to the dramatic theories of Aristotle remains the essential core.

But here’s the rub: Three-act structure produces a disproportionately large act in the middle of a novel���the double-stuff cream in the three-act Oreo���leaving writers with a puffy, gooey act notoriously recognized as the most difficult section to write. Act 2 of a three-act story is twice the length of the other acts, forcing writers to combat the infamous “saggy middle” effect using a hodge-podge of plot tangents and pacing tricks.

But it���s not the writing that makes the double-stuffed Act 2 feel like such a slog; it���s the structure itself. The loss of momentum is a symptom of a missing component that flattens plot and character development: the midpoint complication.

The Frog in the Boiling PotA well-paced story thrives on rising action, tugging readers into a web of progressively escalating complications. This stream of gains and setbacks turns up the heat on the protagonist, like a frog in the proverbial soon-to-boil pot of hot water.

But when complications occur solely at the scene level, readers may not feel as though their hand has been thrust against the blistering heat of the pot. Their experience is more likely to resemble that of our oblivious friend the frog���they may never notice the relentlessly mounting heat. They may lose interest and hop out of the story pot long before it comes to a boil and the frog finally takes action.

While fans of slow-burn stories do exist, most readers prefer regular injections of momentum. And the exciting change they���re looking for���the stuff that sends plots skittering in new directions and forces protagonists to grapple with impossible choices���is driven not by incremental temperature increases but by large-scale structural movement: story turning points.

What Do Turning Points Do?

Turning points are a structural element of storytelling. A turning point is a pivot point between two acts, forming a joint between one limb of the narrative and the next.

It���s not that a turning point is simply a dramatic, landmark event. That���s missing the point. A turning point fills a specific role in the story: It turns the story in a new direction. It keeps the story living, breathing, evolving ��� changing.

Turning points work on the basis of stimulus���response. The first element is a stimulus: a significant action, event, or revelation in the plot. The second element is the protagonist���s response to that stimulus. Their reaction determines the tenor and direction of the entire next act.

Recurring, well-paced turning points keep the story from deteriorating into a dull, predictable march toward an inevitable climax.

And this brings us back to the downfall of three-act structure.

The Midpoint ComplicationWithout a fundamental opportunity for narrative and character change during the second act of a three-act story, readers and writers are likely to flounder. But dividing the second act to create four acts instead of three creates an additional turning point���and another opportunity for the protagonist���s choices to determine the story���s direction.

The midpoint complication, which falls between the two middle acts, offers the perfect story shakeup. It sends the plot in a new direction or complicates the protagonist���s choices with significant new information.

Four-act structure eliminates the long, sagging middle act of three-act structure, prolonging the initial strategy the protagonist chooses at the end of Act 1. The midpoint complication injects new energy into the quest. Readers can visibly see the tides begin to turn. The protagonist���s initial attempts may not be paying off yet, but the hard knocks they���re taking are building determination and resourcefulness.

The midpoint complication serves as a crucial pivot, channeling the story���s energy from reactive response to proactive progress, from the easy way to the hard way, from deconstruction to reconstruction. This form helps writers avoid the common pitfall of the sagging middle act, buoying readers from the first act through the last.

The post The Missing Link in Three-Act Structure appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

August 29, 2024

Does Your Character���s Behavior Make Sense?

Have you been in a situation where someone acts erratically, and not in a good way? It takes you by surprise, doesn���t it? Imagine this scenario: you���re sitting around the lunch table with coworkers and pop out a joke. Instead of a wave of laughter, one of your tablemates begins to sob. Or they jump up, shove the table, and walk out.

Your emotional response? Befuddlement (What just happened?) Guilt (What did I say?) Judgement (Wow, she���s unstable.)

It���s always a bit uncomfortable when we can���t follow the logic of cause and effect. A joke should prompt laughter, head shaking and a grin, or maybe if poorly delivered, an awkward beat of silence. These are reactions we expect.

Cause-and-effect is very important in the real world.

*This sequence helps us navigate life. When we know what to expect, we know what to do.

*Study for a test to pass it.

*Pay the mortgage to have a safe place to live.

It also helps us know what not to do.

*Drinking too much causes a hangover.

*People who leave a paper trail get caught.

*If I tell the boss what I really think, I���ll be fired.

Cause-and-effect helps us plan and gives us a sense of control over our lives.

Guess who else is hardwired to notice cause-and-effect? Readers.

What helps us navigate life also helps readers navigate the story. In fiction, this means paying attention to your character���s behavior. How they react to situations in the story is EVERYTHING. Their decisions, actions, and choices will tell readers what���s really important, what the character wants and needs, who to root for, and what outcome is ideal.

As authors, we want to make it easy for our audience to ���read��� our character���s behavior. If a reader is confused about why a character does or says something it might pull them out of the story, or they could grow frustrated or even lose interest.

So how can we always ���know��� how our characters will behave? By understanding them down to their bones: what they care about, who they are. What they want and fear. What they believe in. By exploring a character���s deeper layers, we learn everything we need to know to determine what they will logically do in any situation. (And knowing this? WRITER���S GOLD. Your story will practically write itself!)

So, whether you like to plan up front or prefer discovery drafts where characters start out as more mystery than flesh, here are important factors that greatly influence how your character will behave.

Emotional RangeEvery person has a baseline when it comes to emotions: reserved or expressive, share feelings openly or keep them to themselves, things like that. Characters are the same. Understanding what this looks like helps us know the difference between ���typical reactions��� and ���escalations.��� After all, conflict and friction will push the needle, causing your character to be more emotionally reactive. It���s great for the story too; emotional extremes push them out of their comfort zone, lead to missteps and mistakes, and create MORE tension and conflict.

To figure out your character���s baseline, imagine everyday situations. How do they express emotion when they feel safe and when they do not? What do everyday emotions (contentment, nervousness, joy, worry, and fear) look like for them?

Once you get a feel for how they show typical emotional responses, this serves as a baseline, and when you add a nice dose of pressure or raise the stakes, you will know what more extreme behaviors and reactions should look like. (More on Determining Emotional Range.)

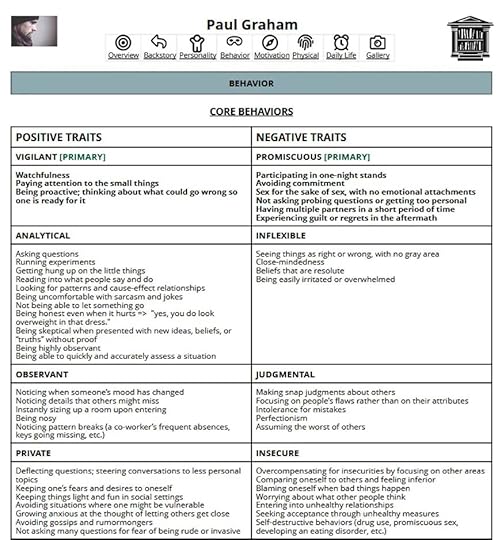

PersonalityTraits that make up your character���s personality steer their behavior. Take Paul Graham, a character I built using the Character Builder at One Stop for Writers. After choosing his personality traits I went through the lists of behaviors and attitudes associated with each to choose ones that fit my vision of him.

Personality traits reveal a character���s moral code, impact how they interact with other characters, how they view the world, and how they go about achieving goals. Here���s a partial screenshot of some of behaviors associated with Paul���s personality traits (via the Character Builder):

Planning Paul���s positive traits helps me see what behaviors will help him solve problems in the story, and his negative traits (especially his primary flaw) shows what behaviors and attitudes hold him back and keep him from his goal. I can also see what he must change about himself (character arc) if he is to achieve his goal. (More on Planning Personality Traits)

BackstoryWe are all products of our past, and characters are too, meaning a character���s history is a huge factor when it comes to their behavior. The people in their lives before the story began acted as either positive influencers (people who taught the character to be self-sufficient, imparted knowledge, and boosted their self-esteem) or negative influencers (people who made your character doubt themselves and their worth, manipulated them, or hurt them in some way).

Both groups have taught your character how to solve problems, in good ways and bad, which will carry forward to your story.

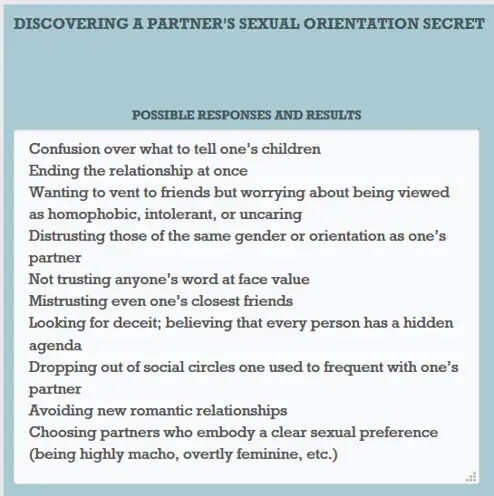

Another huge aspect of backstory are the character���s past experiences. Good ones give them a positive outlook and worldview, and negative ones create emotional wounds. These painful negative events are transformative: who the character is before a wounding event and who they are afterward are very different. Paul���s wound was finding out his wife was not who she thought she was, and this was the fallout:

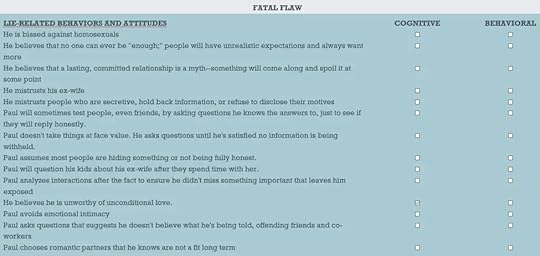

Because an emotional wound makes a person afraid that they could be hurt the same way again, they protect themselves by changing their behavior, often in negative ways that we call Emotional Shielding. These dysfunctional behaviors and attitudes are meant to keep people and situations at a distance so they cannot hurt the character. Unfortunately, emotional shielding also keeps a character chained to fear and ultimately gets in the way of what they want most. Here���s a partial list of Paul���s dysfunctional behaviors and attitudes: ��

Reading through these, you can see how they are dysfunctional and will cause problems for Paul. Past hurts always reveal emotional sensitivities and fears, which influence a character���s actions.

Character MotivationWhile a character enters the story with a lot of baggage and ���set��� behaviors, one factor can change everything: their motivation. What they want most in the story is powerful. Their goal, if achieved, can fill the hollowness inside them and erase the unmet need that keeps them from feeling happy and complete.

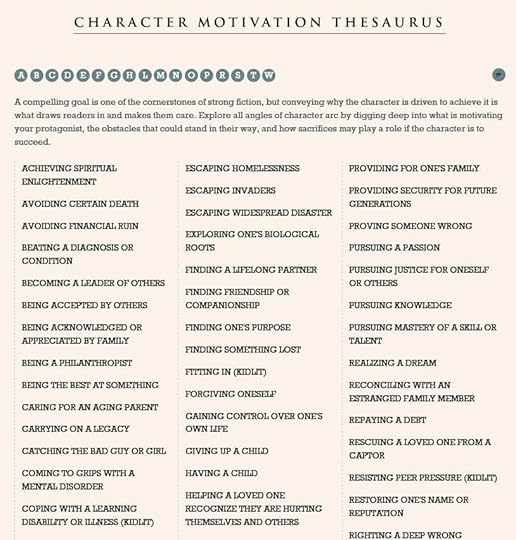

No matter how many hurts your character has endured, what they fear most, or how jaded they are at the world, they can and will change if it means getting what they want most. Here is a sampling of common character motivations:

A strong story goal should not be easy to obtain, and will require the character to transform their mindset and behavior to achieve it. So knowing the goal will also help you know how they will behave, especially as they grow and evolve.

Bottom line, readers want books written by authors who show authority. This authority comes from knowing a character so intimately that every action, choice, and decision rings true. Readers should have no trouble following cause-and-effect.

If you need help seeing how all the character pieces fit together, try the Character Builder.

If you need help seeing how all the character pieces fit together, try the Character Builder. It contains the largest character-centric database of information available anywhere and prompts you to go deeper step by step, making character building much easier.�� ��

As a reader, does it bother you when characters behave in a way that isn���t explained? Let me know in the comments!

The post Does Your Character���s Behavior Make Sense? appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS��.

Writers Helping Writers

- Angela Ackerman's profile

- 1022 followers