Michael Roberts's Blog, page 28

August 21, 2022

Will global inflation subside?

Is the global inflationary spiral peaking? And if it is and inflation is set to fall over the next year, then has the inflation scare been just a momentary blip and now things will start to turn back to the previously low pace of inflation in the prices of goods and services?

That seems to the view of investors in financial assets in the US, where the stock market has rallied by as much as 20% from lows in mid-June; and both government and corporate bond yields have steadied. Markets seem to believe in what is called the ‘Fed pivot’, where the US Federal Reserve, having hiked its policy rate aggressively since April, will now start to end its hikes going into 2023 as inflation subsides.

Certainly, there is some evidence of peaking inflation in the US where the consumer price inflation (CPI) rate slowed more than expected in July to 8.5% year over year from a 40-year high of 9.1% in June. But looking beneath the headline rate, it is less convincing that US inflation is heading downwards, at least at any significant pace. The slowing in July was mainly due to falling gasoline prices. Food inflation (10.9%) and electricity price inflation (15.2%) continued to accelerate. And stripping out food and energy, the so-called ‘core’ inflation rate stayed steady at 5.9%.

Source: Fred

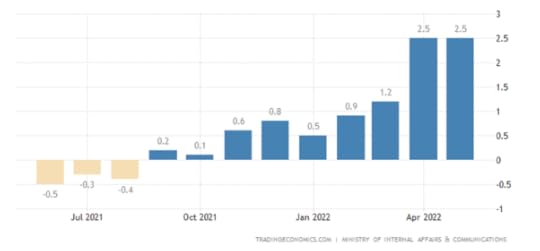

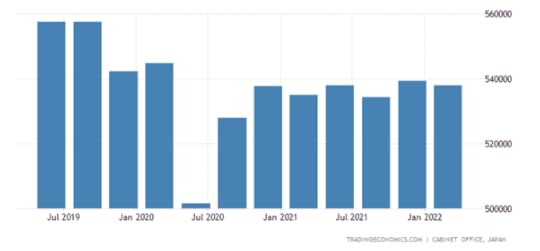

And outside the US, there is still little sign of peaking. The Eurozone inflation rate rose in July to 8.9% yoy, while the UK rate hit double-digits (10.1%), with the Bank of England forecasting a peak of 13%-plus by early 2023, and other forecasters calling a 15% rate. Even Japan, the economy of stagnation and deflation for decades, achieved a 2.6% yoy rate in July. This was the 11th straight month of increase in consumer prices and the fastest pace since April 2014.

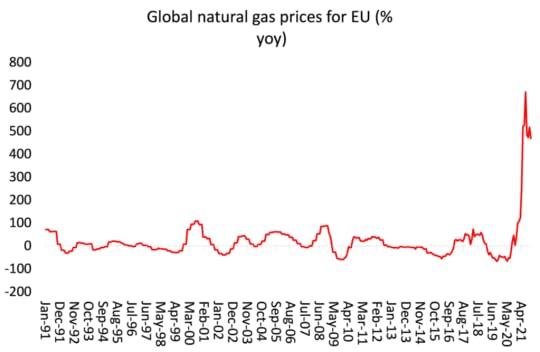

Nevertheless, perhaps there are signs globally down the road that inflation rates will ease at least during 2023. Crude oil prices are still 40% above a year ago, but prices have fallen from their peak of $120/b in June to $90/b. That should feed through to energy prices, at least for transport fuel. In contrast, natural gas prices are at all-time highs. This is particularly bad news for Europe, which depends heavily on gas imports from Russia.

The EU is trying to impose sanctions (including energy sanctions) against Russia over the invasion of Ukraine. But that means searching for new sources of supply, the competition for which globally is driving up prices. A combination of tight supplies and soaring demand amid persistent heatwaves across Europe (including a historic drought triggered by an arid summer that set heat records across Europe), threatens to halt energy shipments along the Rhine River while limiting hydroelectric and nuclear power production. At the same time, Russia’s Gazprom keeps reducing flows through the Nord Stream pipeline (now down to roughly 20% of its capacity), citing issues with turbines. So energy prices in Europe could rise even further as winter approaches.

Source: Fred

The other driver of inflation has been food. And here at last global food prices have dropped from all-time peaks, particularly after the agreement brokered between Russia and Ukraine to allow grain shipments through the Black Sea to world markets. But commodity prices in general remain over 50% higher than this time last year.

Source: FRED

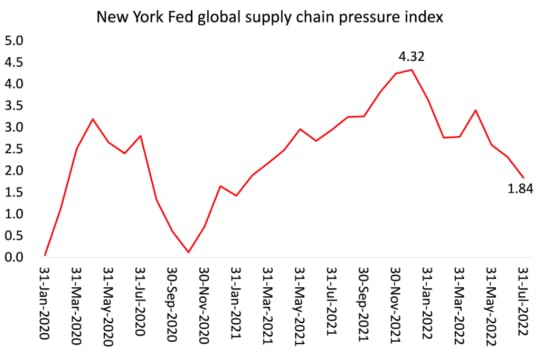

And that other key driver of global inflation, post the COVID slump, supply chain blockages, caused by lockdowns, loss of staff, lack of components and the slow regearing of transport logistics, is finally showing some easing. Even so, the New York Fed global supply chain pressure index (GSCPI), that measures various indicators of container ship and port blockages, is still much higher than before the COVID pandemic began.

Source: New York Fed

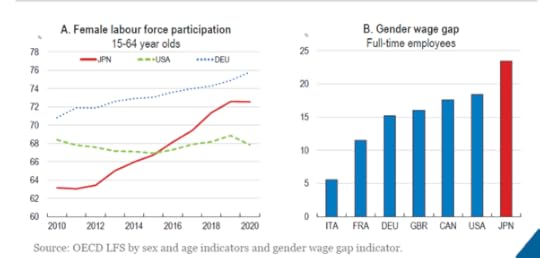

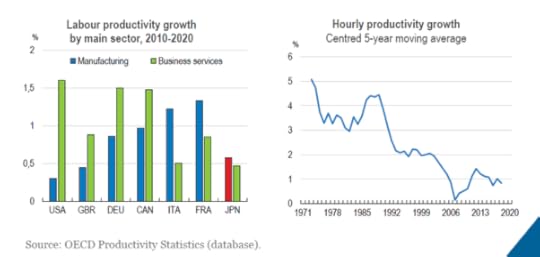

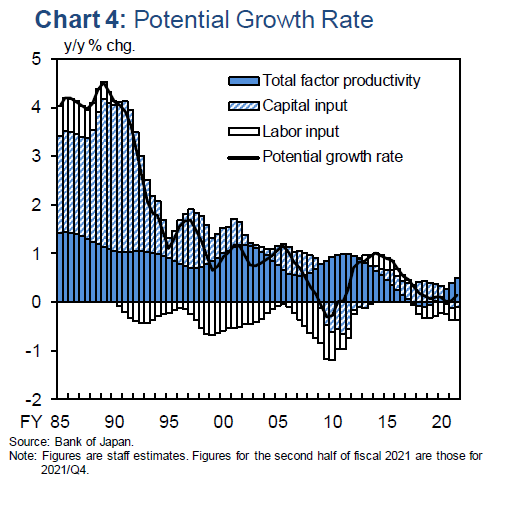

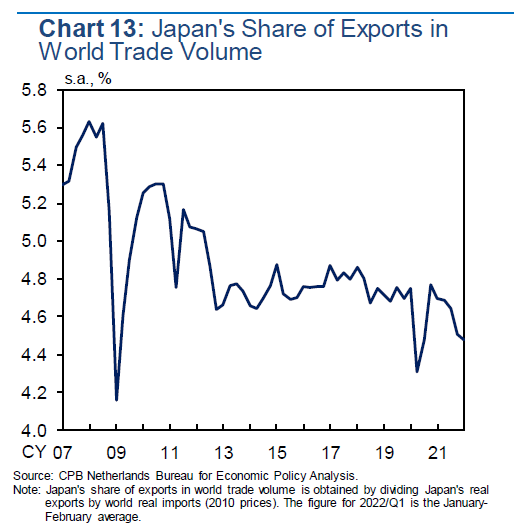

And take all this evidence of moderating inflation with considerable caution: for at least three reasons. The first is that central banks have no control over the pace of inflation because rising prices have not been driven by ‘excessive demand’ from consumers for goods and services or by companies investing heavily, or even by uncontrolled government spending. It’s not demand that is ‘excessive’, but the other side of the price equation, supply, is too weak. And there, central banks have no traction. They can hike policy interest rates as much as they deem, but it will have little effect on the supply squeeze. And that supply squeeze is not just due to production and transport blockages, or the war in Ukraine, but in my view, even more so to an underlying long-term decline in the productivity growth of the major economies.

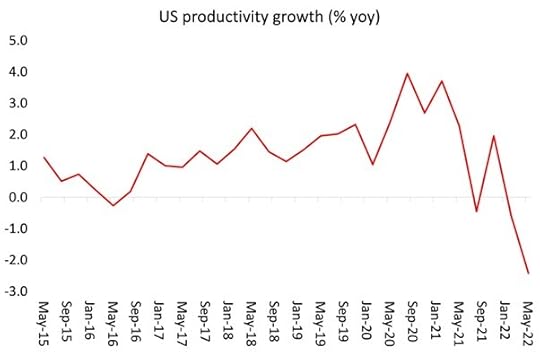

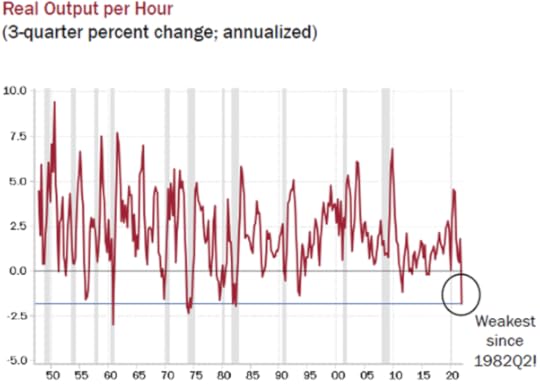

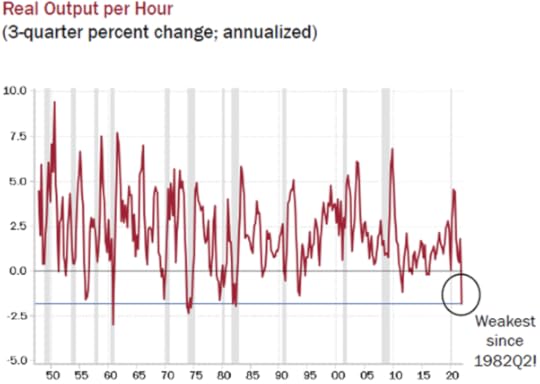

So the second reason for not expecting a sharp fall in inflation rates is that productivity growth has slowed so much that the supply-side cannot respond adequately to the recovery in demand for goods and services as economies came out of the COVID slump. For example, US productivity of labour (output per employee) has taken a huge tumble in the first half of 2022, down 3% over two quarters, the biggest half-yearly fall since records began.

Source: BEA, author

Official figures tell us that US employment is rising. But at the same time, the latest US real GDP figures show that national output fell in the first half of this year. That is the arithmetical reason for why US productivity has fallen. But the underlying causal explanation is to be found in the long-term tendencies in the US economy; and not just there, but in most of the major economies.

The key to sustained long-term real GDP growth is high and rising productivity of labour. But productivity growth has been slowing towards zero in the major economies for over two decades and particularly in the Long Depression since 2010. US labour productivity growth is now at its weakest for 40 years. Indeed, before the COVID pandemic, the world economy was already slowing down towards a slump after ten years of a Long Depression.

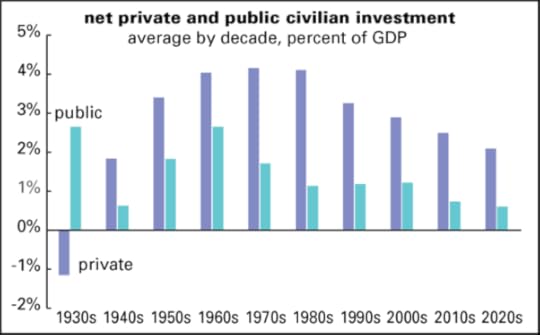

The productivity crisis is driven by two factors: first, slowing investment growth in productive (ie value-enhancing) sectors compared to unproductive sectors (like financial markets, property and military spending). As a percentage of GDP, US productive investment has steadily fallen, both in net private and public civilian investment.

Source: Federal Reserve, Doug Henman

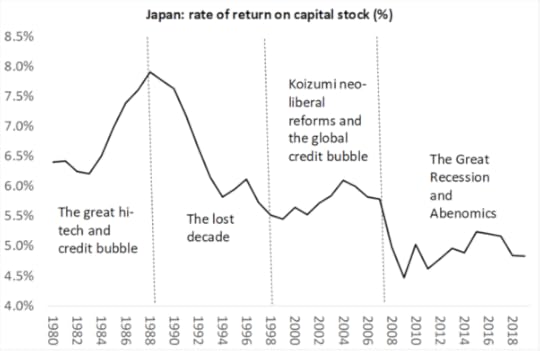

And second, behind this decline in productive investment is the long-term decline in the profitability of such investment compared to investing in financial assets and property. Profitability of investment in the main value-creating sectors is near post-1945 lows.

SOURCE: BEA, Basu-Wasner, author

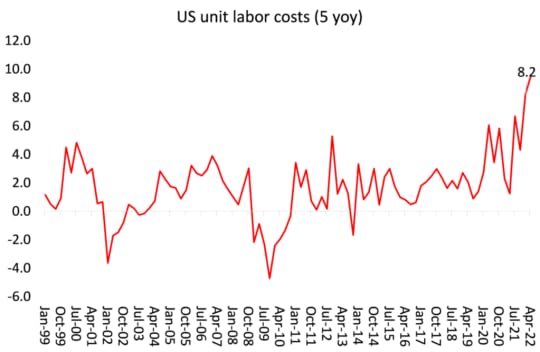

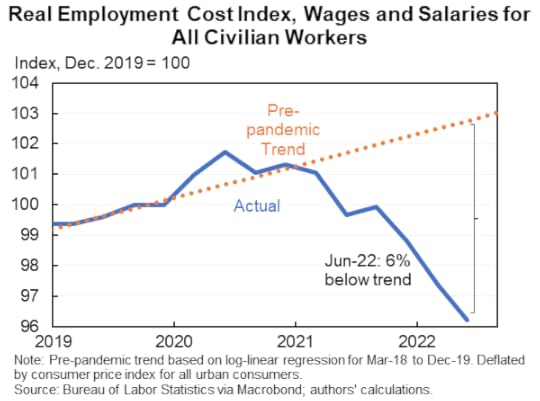

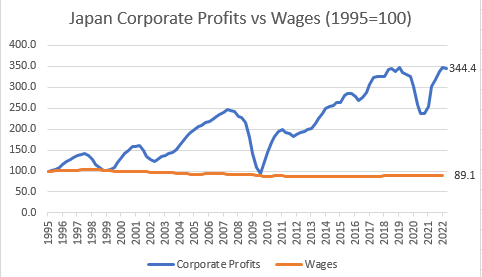

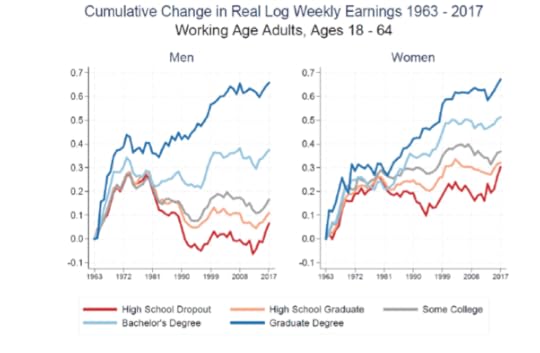

That brings me to my third reason for caution on inflation subsiding: the risk of increased wage demands driving up prices. When productivity growth is low, even small wage rises demanded by employees can sharply raise employee costs per unit of output. Companies are then forced to take a hit on their profits and/or try to raise prices to compensate. A so-called wage-price spiral could ensue. At least that’s the claim of the mainstream theory.

Source: FRED

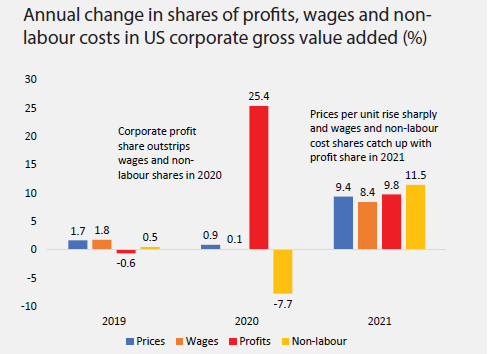

So far, that has not happened. And the mainstream economics charge that wage rises are causing the current inflation acceleration or even that future wage rises will do so is not backed by evidence historically.

Instead, average real wages have been falling sharply. The IMF reckons that the average European household will see a rise of about 7 percent in its cost of living this year relative to what was expected in early 2021. Employees everywhere are now trying to restore living standards through wage rise demands, in Europe and the US. If they are successful, this will most likely lower profits. Already, after reaching all-time highs, US corporate profit margins have begun to fall.

Source: BEA, author

That means the major economies could enter a period of stagflation, not seen since the late 1970s, where inflation rates stay high, but output stagnates. Indeed, it could be worse than that. The risk of an outright global slump is rising. If central banks continue to hike their policy rates, all that will do is increase of cost of borrowing for consumers and companies, driving weaker companies into bankruptcies and suppressing demand across the board. Sure, that may finally reduce inflation but only through a slump.

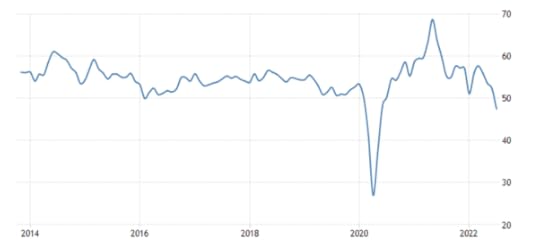

The recovery from the COVID slump of 2020 has petered out. The world economy is teetering on a slump according to the latest data by JP Morgan economists. Their measure of global economic activity (global PMI output) has slipped to 50.8 (anything below 50 is a recession), which is a 25-month low. JPM say that the 50.8 measure is equivalent to a world economic growth rate of just 2.2%. That’s near ‘stall speed’ and remember includes China, India and other large economies. The global manufacturing sector is on the cusp of contraction and the services sector is slowing fast.

As the IMF puts it, “The global outlook has already darkened significantly since April. The world may soon be teetering on the edge of a global recession, only two years after the last one.” says the IMF in its latest economic forecast. The IMF has reduced its forecasts for global economic growth. Under its baseline forecast, the IMF now expects world real GDP growth to slow from last year’s 6.1 percent to 3.2 percent this year and 2.9 percent next year (2023). This forecast slowdown from 2021 to 2022 is the biggest one-year drop in economic growth in 80 years! “This reflects stalling growth in the world’s three largest economies—the United States, China and the euro area—with important consequences for the global outlook.” At the same time, the IMF forecast for the inflation rate has been revised up. Inflation this year is anticipated to reach 6.6 percent in advanced economies and 9.5 percent in emerging market and developing economies and is projected to remain elevated longer.

And these are the baseline forecasts for growth with the risks “overwhelmingly tilted to the downside.” There is a risk that “inflation will rise and global growth decelerate further to about 2.6 percent this year and 2 percent next year—a pace that growth has fallen below just five times since 1970. Under this scenario, both the United States and the euro area experience near-zero growth next year, with negative knock-on effects for the rest of the world.”

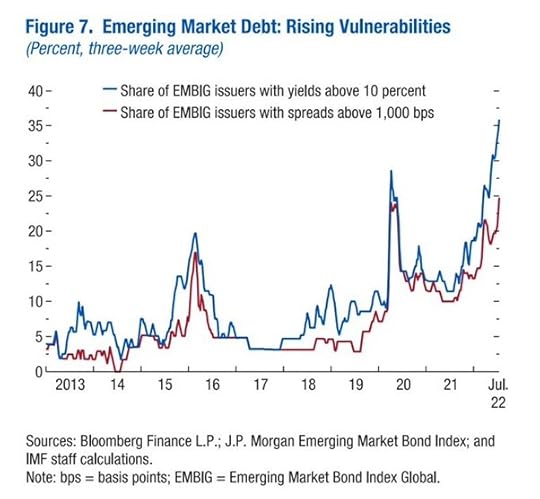

It will be even worse in the so-called developing countries: “many countries lack fiscal space, with the share of low-income countries in or at high risk of debt distress at 60 percent, up from about 20 percent a decade ago. Higher borrowing costs, diminished credit flows, a stronger dollar and weaker growth will push even more into distress.” The share of emerging market bond issuers with yields above 10% is now higher than at any time since 2013.

Source: IMF

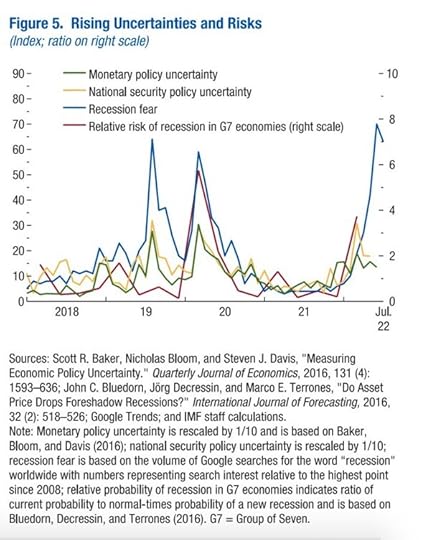

Recession fear is now at levels worldwide last seen in 2020.

At the very least, global inflation rates are still likely to be much higher than before the COVID pandemic by this time next year – and at the worst, the global economy could have entered a new slump only three years from the last one.

August 14, 2022

Russia under Putin

In my last post, I described how Western capital is planning to take over and control Ukraine’s resources and exploit its labour force to the maximum in order to boost the profitability of both Ukraine’s domestic capitalists (oligarchs) and foreign multi-nationals.

However, there is a problem for Western capital and Ukraine’s oligarchs: it’s Russia. The war has already led to Russian forces gaining control of at least $12.4trn worth of Ukraine’s resources in energy (cola), metals and mineral deposits, apart from agricultural land. If Putin’s forces succeed in annexing Ukrainian land seized during Russia’s invasion, Kyiv would permanently lose almost two-thirds of its deposits. Moscow now controls 63% of Ukraine’s coal deposits, 11% of its oil, 20% of its natural gas, 42% of its metals, and 33% of its rare earths.

So any rebuilding effort funded by Western capital has a major obstacle. “Not only will Ukraine have lost a lot of its territory and its resources, but it would be constantly vulnerable to another onslaught by Russia,” said Jacob Kirkegaard, a fellow at the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics. “No one in their right mind, a private company, would invest in the rest of Ukraine if this were to become a frozen conflict.” Ukraine has suffered continual bombing and military attacks with thousands of civilians dying and millions having to flee their homes and even leave the country. If Russia maintains its control of existing gains, the reconstruction of Ukraine as an independent state based funded by Western capital is put in jeopardy.

And many Russian-speaking Ukrainians and others will remain under the control of Russia. Ukraine’s working people are having their trade union rights and working conditions degraded by the nationalist Zelensky government. Under Putin’s Russia, it would even be worse. For in Russia, going on strike, demonstrating against the regime and organizing politically is already fraught with danger and even death (although Ukraine is heading the same way).

When the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s, the elite in Russia, with the enthusiastic backing of US imperialism and Western economic advisers, moved quickly to dismantle the Soviet state sector. There was no attempt to introduce even ‘liberal democracy’. Much more important was to gain control of Russia’s resources and labour for private profit. The pro-capitalist hero Yeltsin quickly launched what has become called a ‘shock therapy’ introduction of markets and private capital. Prices were ‘liberalised’ and rapid privatisation began—all by presidential decree without any democratic mandate from the Russian people. Yeltsin pushed through a constitution which enshrined a powerful president with strong decree and veto powers.

When price controls were lifted, the prices for basic foodstuffs like bread and butter skyrocketed by as much as 500 percent in a matter of days. Large sections of the population sank into deep poverty almost overnight. By 1994, about 70 percent of the Russian economy was privatised. Yeltsin achieved this by selling off Russia’s assets for peanuts to a cabal of favoured people, now called ‘oligarchs’

During the seven years of the Yeltsin regime, Russia’s GDP fell 40% and numerous bouts of hyperinflation wiped out the savings of many Russian citizens. Crime was rampant; mafia ran protection schemes on businesses and officials demanded bribes. Life expectancy plummeted. Kleptocracy and extreme inequality were permanently embedded.

Alcoholic Yeltsin became extremely unpopular (his approval rating fell to just 10%). But the new cabal of oligarchs made sure he was re-elected in 1996 through a plan drawn up by Western strategists at that year’s Davos World Economic Forum and delivered through a massive campaign in the controlled media and through the sidelining of any opposition campaign (then mainly the Communists). However, the economy still struggled to recover and in 1998, the Russian government defaulted on $40 billion of short-term government bonds, devalued the ruble, and declared a moratorium on payments to foreign creditors.

This catastrophic default crippled the Yeltsin government and led to Yeltsin stepping down as president just over a year later. Yeltsin made way for his prime minister Vladimir Putin. Putin, a former KGB officer, promised to establish stability and prosperity with reforms. He restored discipline and order to the government; made the State Duma—Russia’s parliament—subordinate to his will; ended elections of regional governors and turned them into appointed officials, centralising authority; seized control of the media; and cracked down on any resistant oligarchs, exiling or imprisoning many of them.

A new elite emerged that replaced many of the oligarchs of the Yeltsin years. These were individuals close to Putin dating back to his days in the KGB or when he served as deputy mayor of St. Petersburg in the 1990s. Because of their close ties to Putin, they were able to gain control over important sectors of the Russian economy and became heads of state companies that grew following the nationalization of assets of many of the former Yeltsin-era oligarchs. Step-by-step Putin created a state of crony capitalism that was bolstered by the so-called siloviki—powerful figures from the security and military services—who were active participants in Putin’s increasingly corrupt system.

Putin was lucky. During his first two terms as president (2000–2004, and 2004–2008), the Russian economy prospered and the people shared to some extent in this brief economic boom. Average annual real GDP growth reached 5.5%. But this was only due to the commodity price boom that also helped many weaker capitalist economies like Chavez’s Venezuela or Lula’s Brazil. Oil prices surged from a low of $10 a barrel to a peak of $150 a barrel.

But those relatively ‘golden years’ based on energy exports came sharply to an end with the Great Recession of 2008-9 and the subsequent Long Depression of the 2010s when the commodities boom dissipated. Stagnation set in. Real GDP growth in the next decade averaged only 2%.

Foreign investment declined precipitously and capital flight accelerated to nearly 4% of annual GDP as the oligarchs (including Putin) spirited their ill-gotten gains into offshore havens or property in the UK, with the help of Western investment and legal companies and government tax incentives.

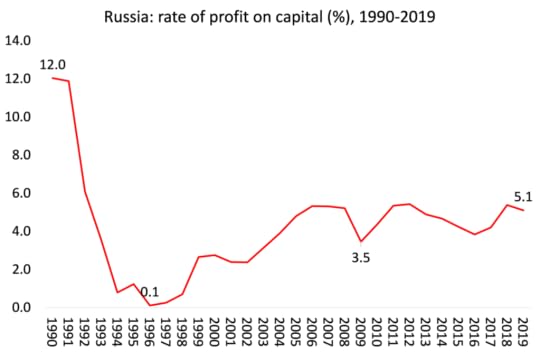

Productive investment growth was weak because the profitability of capital in Russia only slowly recovered from the ‘shock therapy’ years. This is graphically revealed by the trend in the profitability of Russian capital. After the ‘shock therapy’ economic collapse, profitability had recovered during the ‘golden years’ of Putin’s first two terms. But after 2007, profitability marked time; while economic growth crawled along.

So in Putin’s third term (after 2012), the regime became even more nationalist and autocratic, cracking down on any credible opposition with intimidation, force and even assassination. And 2014 saw a significant turning point. Putin promoted the 2014 Winter Olympics, which cost more than $50 billion—the most expensive Olympic Games ever. Much of the funding came from Putin’s billionaire cronies. So when the nationalist government in Ukraine launched its attacks on the Russian-speaking areas after the Maidan coup, Putin responded by annexing Crimea and providing active support for the separatists in the Donbas region. This boosted his popularity at home, turning attention away from the failure of the domestic economy, at least for a while, and his approval rating rocketed.

But the economy did not rocket. The West then applied economic sanctions against Russian business figures and sectors. Russia’s growth remained weak and below the growth rate in most developed countries. When adjusted for inflation, the average Russian was making less money in 2019 than in 2014.

Soon after he was first appointed president in 2000, Putin published an essay claiming that he wanted Russia to reach Portugal’s level of GDP per capita by the end of his two terms in office. Portugal was then the poorest EU member state. However, two decades later in 2021, Portugal’s GDP per capita in current dollars is twice as high as Russia’s. Despite the damage suffered by Portugal during the 2010 euro debt crisis, Russia has actually fallen further behind the Portuguese economy.

Amid stagnation, inequality has accelerated. According to joint research by the Higher School of Economics and the state-run VEB Bank, “the wealthiest 3 percent of Russians owned 89 percent of all financial assets in 2018.” The Moscow Times reports “the number of billionaires in Russia grew from 74 to 110 between mid-2018 and mid-2019, while the number of millionaires rose from 172,000 to 246,000.” According to Forbes’s rating, the total wealth possessed by Russia’s top 200 in 2019 was $15 billion higher than it had been in 2014.

In contrast, Rosstat reported last year that 14.3 percent of the population (21 million people) can be defined as poor. According to Yale economist Christopher Miller, Russians are getting poorer. The year “2018 marked the fifth straight year in which Russians’ inflation-adjusted disposable incomes fell.” Rosstat further reports that “almost two-thirds (63.5%) of Russian households only have enough money to buy food, clothes and other essential items.” The Russian Central Bank reported that 75 percent of the population is not able to save anything each month and almost one-third of those who manage to put some money into savings do so by skimping on food.

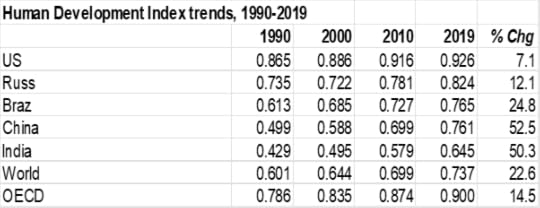

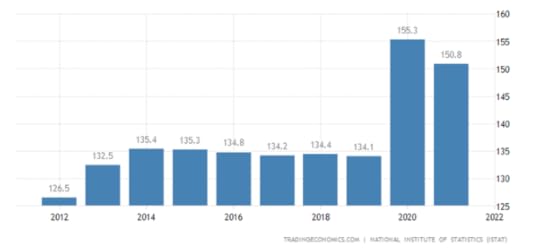

Just how badly Russia’s crony capitalist regime under Putin has performed for the average Russian is revealed in the UN’s human development index (HDI), which covers life expectancy, employment, incomes and other services. Russia’s HDI measure has grown the least of the major ‘emerging economies’ and is now way below the OECD average.

All this makes a joke of the arguments in the Western media that Putin’s regime is some sort of reversion to the Soviet state. For a start, Putin has often attacked ‘Bolshevism’ and, in particular the views of Lenin that nations like Ukrainians had a right to self-determination. Instead, Putin has turned to the feudal imperialism of Russia’s Peter the Great as his model for the invasion of Ukraine. Putin has eulogized Peter’s conquests in the Great Northern War and praised him for “returning” historically Russian lands. “It seems that it has fallen to us, too, to return (Russian lands),” Putin commented. For him, Ukraine is not a nation but part of Russia, which the nationalist in Kyev and Western powers are tryng to separate.

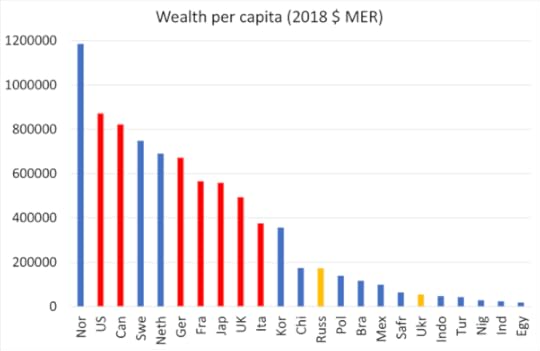

The irony is that Putin’s imperialist ambitions for control of the peripheral countries of the former Soviet Union are not backed up by a modern imperialist economy. Russia is not in the imperialist league, as I have shown in previous posts. Russia is no super power, economically or politically. Its total wealth (including labour and natural resources) is way down the league compared to the US and the G7 (red bars). And even its supposed military might has been exposed as a paper tiger.

The Russia economy remains a ‘one-trick pony’, depending on oil and gas that make up more than half its exports before the war started, with the rest being grain, chemicals and metals – no advanced technology exports. That means that far from extracting surplus value through trade with other countries, instead, the more advanced capitalist economies and their multi-nationals get net transfers of surplus value from Russia.

Putin may think Russia can be an imperialist power, but the economic reality is that Russia is just a large peripheral economy outside the US-led imperialist bloc like Brazil, China, India, South Africa, Turkey, Egypt etc – if with a larger military than most. Seriously opposing that bloc leads to conflict, as China now faces.

August 13, 2022

Ukraine: the invasion of capital

Last week, Ukraine’s foreign private creditors agreed to the country’s request for a two-year freeze on payments on about $20bn of foreign debt. This would enable Ukraine to avoid defaulting on its overseas borrowings. Unlike other ‘emerging economies’ in debt distress, it seems that foreign bondholders are happy to help Ukraine out – if only for two years. The move will save Ukraine $6bn over the period, helping to reduce pressure on central bank reserves, which slid by 28 per cent year-to-date, despite significant foreign aid.

Ukraine’s economy is, not surprisingly, in a desperate state. Real GDP is projected to decline by more than 30% in 2022 and the unemployment rate is at 35% (Constantinescu et al. 2022, Blinov and Djankov 2022, National Bank of Ukraine 2022). “We are grateful for the private sector support of our proposal in such terrible times for our country,” responded Yuriy Butsa, Ukraine’s deputy finance minister, “I’d like to emphasise that the support we’ve received during this transaction is hard to underestimate . . . We will stay fully engaged with the investment community further on and hope for their involvement in the financing of the rebuilding of our country after we win the war,” Butsa said.

Here Butsa reveals the price to pay for this limited largesse by foreign creditors.: the accelerating demand of foreign multi-nationals and governments to take control of Ukraine resources and bring them under the control of foreign capital without any restrictions and limitations.

In a past post, I had outlined the plan to privatise and hand over the vast agricultural resources of Ukraine to foreign multi-nationals. And for several years now, a series of reports by the Oakland Institute economic observatory has documented the takeover of foreign capital. Much of what is below comes from Oakland.

Post-Soviet Ukraine, with its 32 million arable hectares of rich and fertile black soil (known as “cernozëm”), has the equivalent of one-third of all existing agricultural land in the European Union. The “breadbasket of Europe,” as it is called, had an annual production of 64 million tons of grain and seeds, among the world’s largest producers of barley, wheat and sunflower oil (for the latter, Ukraine produces about 30 percent of the world total).

As I explained in my previous post, the planned takeover of Ukraine’s resources partly provoked the conflict: the semi-civil war, the Maidan revolt and the annexation of Crimea by Russia. As the Oakland Institute has outlined, to limit unrestrained privatization, a moratorium on the sale of land to foreigners had been imposed in 2001. Since then, the repeal of this rule has been a main goal of Western institutions. As early as 2013, for instance, the World Bank provided an $89 million loan for the development of a deed and land title program needed for the commercialization of state-owned and cooperative land. In the words of a 2019 World Bank paper the aim was an “accelerating of private investment in agriculture.” That agreement, denounced at the time by Russia as a backdoor to facilitating the entry of Western multinationals, includes the promotion of “modern agricultural production … including the use of biotechnologies,” an apparent opening towards GMO crops on Ukrainian fields.

Despite the moratorium on land sales to foreigners, by 2016, ten multinational agricultural corporations had already come to control 2.8 million hectares of land. Today, some estimates speak of 3.4 million hectares in the hands of foreign companies and Ukrainian companies with foreign funds as shareholders. Other estimates are as high as 6 million hectares. The moratorium on sales, which the US State Department, IMF and World Bank had repeatedly called to be removed, was finally repealed by the Zelensky government in 2020, ahead of a final referendum on the issue scheduled for 2024.

Now with war grinding on, Western governments and corporations are stepping up their plans to incorporate Ukraine and its resources into the capitalist economies of the West.On July 4 and 5, 2022, top officials from the US, EU, Britain, Japan, and South Korea met in Switzerland for a so-called “Ukraine Recovery Conference.”

The URC’s agenda was explicitly focused on imposing political changes on the country – namely, “strengthening the market economy“, “decentralization, privatization, reform of state-owned enterprises, land reform, state administration reform,” and “Euro-Atlantic integration.” The agenda was really a follow-up to the 2018 Ukraine Reform Conference which had emphasized the importance of privatizing most of Ukraine’s remaining public sector, stating that the “ultimate goal of the reform is to sell state-owned enterprises to private investors”, along with calls for more “privatization, deregulation, energy reform, tax and customs reform.” Lamenting that the “government is Ukraine’s largest asset holder,” the report stated, “Reform in privatization and SOEs has been long awaited, as this sector of the Ukrainian economy has remained largely unchanged since 1991.”

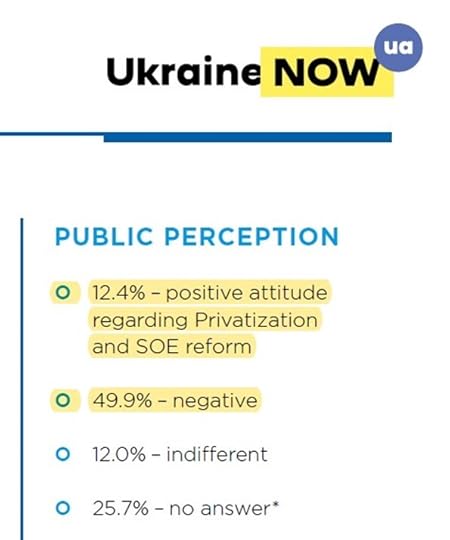

The irony is that the 2018 URC plans were opposed by most Ukrainians. A public opinion poll found that just 12.4% supported privatization of state-owned enterprises (SOE), whereas 49.9% opposed it. (An additional 12% were indifferent, whereas 25.7% had no answer.)

However, war can make all the difference. In June 2020, the IMF approved an 18-month, $5 billion loan program with Ukraine. In return, the Ukraine government lift[ed] the 19-year moratorium on the sale of state-owned agricultural lands, after sustained pressure from international finance institutions.. Olena Borodina with the Ukrainian Rural Development Network commented that, “the agribusiness interests and oligarchs will be the primary beneficiaries of such reform…[This] will only further marginalize smallholder farmers and risks severing them from their most valuable resource.”

And now July’s URC has re-emphasised its plans to take over the Ukraine economy for capital, with the full endorsement of Zelensky government. At the conclusion of the meeting, all governments and institutions present endorsed a joint statement called the Lugano Declaration. This declaration was supplemented by a “National Recovery Plan,” which was in turn prepared by a “National Recovery Council” established by the Ukrainian government.

This plan advocated for an array of pro-capital measures, including “privatization of non critical enterprises” and “finalization of corporatization of SOEs” (state-owned enterprises) – identifying as an example the selling off of Ukraine’s state-owned nuclear energy company EnergoAtom. In order to “attract private capital into banking system,” the proposal likewise called for the “privatization of SOBs” (state-owned banks). Seeking to increase “private investment and boost nationwide entrepreneurship,” the National Recovery Plan urged significant “deregulation” and proposed the creation of “‘catalyst projects’ to unlock private investment into priority sectors.”

In an explicit call for slashing labour protections, the document attacked the remaining pro-worker laws in Ukraine, some of which are a holdover of the Soviet era. The National Recovery Plan complained of “outdated labor legislation leading to complicated hiring and firing process, regulation of overtime, etc.” As an example of this supposed “outdated labor legislation,” the Western-backed plan lamented that workers in Ukraine with one year of experience are granted a nine-week “notice period for redundancy dismissal,” compared to just four weeks in Poland and South Korea.

In March 2022, the Ukrainian parliament adopted emergency legislation allowing employers to suspend collective agreements. Then in May, it passed a permanent reform package effectively exempting the vast majority of Ukrainian workers (those at businesses with fewer than 200 employees) from Ukrainian labor law. Documents leaked in 2021 showed that the British government coached Ukrainian officials on how to convince a recalcitrant public to give up workers’ rights and implement anti-union policies. Training materials lamented that popular opinion towards the proposed reforms was overwhelmingly negative, but provided messaging strategies to mislead Ukrainians into supporting them.

While workers’ rights are to be removed in the ‘new Ukraine’, in contrast the National Recovery Plan aims to help corporations and the wealthy by lowering taxes. The plan complained that 40% of Ukraine’s GDP came from tax revenue, calling this a “rather high tax burden” compared to its model example of South Korea. It thus called to “transform tax service,” and “review potential for decreasing the share of tax revenue in GDP.” In the name of “EU integration and access to markets,” it likewise proposed “removal of tariffs and non-tariff non-technical barriers for all Ukrainian goods,” while simultaneously calling to “facilitate FDI [foreign direct investment] attraction to bring the largest international companies to Ukraine,” with “special investment incentives” for foreign corporations.

In addition to the National Recovery Plan and the strategic briefing, the July 2022 Ukraine Recovery Conference presented a report prepared by the company Economist Impact, a corporate consulting firm that is part of The Economist Group. The Ukraine Reform Tracker pushed to “increase foreign direct investments” by international corporations, not invest resources in social programs for the Ukrainian people. The Tracker report emphasized the importance of developing the financial sector and called for “removing excessive regulations” and tariffs. It called for further “liberalising agriculture” to “attract foreign investment and encourage domestic entrepreneurship,” as well as “procedural simplifications,” to “make it easier for small and medium enterprises” to “expand by purchasing and investing in state-owned assets,” thereby “making it easier for foreign investors to enter the market post-conflict.”

The Ukraine Reform Tracker presented the war as an opportunity to impose the take over by foreign capital. “The post-war moment may present an opportunity to complete the difficult land reform by extending the right to purchase agricultural land to legal entities, including foreign ones,” the report stated. “Opening the path for international capital to flow into Ukrainian agriculture will likely boost productivity across the sector, increasing its competitiveness in the EU market,” it added. “Once the war is over, the government will also need to consider substantially lowering the share of state owned banks, with the privatisation of Privatbank, the country’s largest lender, and Oshchadbank, a large processor of pensions and social payments,” it insisted.

Elsewhere there are less explicit pro-capital polices offered by semi-Keynesian Western economists. In a recent compilation by the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), various economists have proposed Macroeconomic Policies for Wartime Ukraine. In this the authors “emphasise at the outset that Ukraine’s crisis is not a setting for a typical macroeconomic adjustment programme. ie not the usual IMF fiscal austerity and privatisation demands. But after many pages, it becomes clear that there is little difference in their proposals than those of the URC. As they say “the aim should be to pursue extensive radical deregulation of economic activity, avoid price controls, facilitate matching of labour and capital, and enhance the management of seized Russian and other sanctioned assets.“

The takeover of Ukraine by capital (mainly foreign) will thus be completed and Ukraine can start paying back its debts and providing new profits for Western imperialism.

August 7, 2022

The IRA and the four horsemen of the climate apocalypse

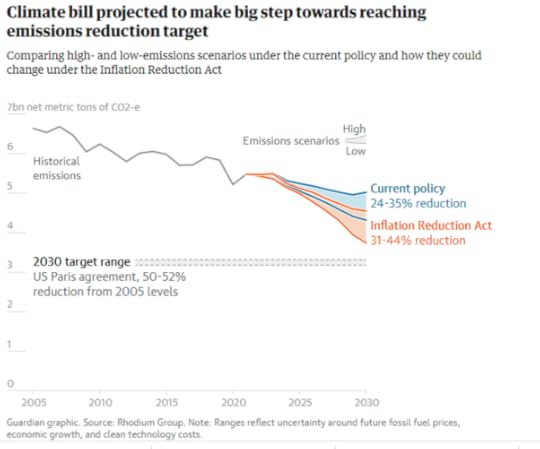

The announcement that US President’s Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has got the backing of pro-business, coal-mining owner Democratic Senator Manchin has been greeted with a wave of optimism that the US target of cutting carbon emissions in half before the end of this decade (or 40% compared with 2005 levels), can be met. “This bill will really turbocharge that transition to clean energy, it will transform markets where already solar PV, wind and batteries are in many cases cheaper than incumbent fossil fuels,” said Anand Gopal, executive director of policy at Energy Innovation, an open source research body. “Increasingly I’m more optimistic that keeping the temperature rise under 2C (3.6F) is more reachable. 1.5C is a stretch goal at this point.”

The bill will cut US emissions by between 31% and 44% below 2005 levels by 2030, according to Rhodium Group, a non-partisan research firm. A separate analysis by Energy Innovation, another research house, has found a similar reduction, of between 37% and 41% this decade.

But will it do the trick of saving the planet? First, the IRA has to get through Congress and even after a huge watering down of the bill to accommodate Manchin, there is still no certainty that it will get past a Republican opposition. As it is, the bill actually allows for an expansion of oil and gas drilling in national parks and land as a sop to Manchin. There may be yet more concessions to the fossil fuel lobby.

Then there are actual measures proposed in the IRA. “This is a massive turning point,” argues Leah Stokes, a climate policy expert at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “This bill includes so much, it comprises nearly $370bn in climate and clean energy investments. That’s truly historic. Overall, the IRA is a huge opportunity to tackle the climate crisis.” But is it? Much of the bill is really tax credits to companies to invest in clean energy projects as well as a rebate of up to $7,500 for Americans who want to buy new electric vehicles. There is $9bn to retrofit houses to make them more energy efficient, tax credits for heat pumps and rooftop solar and a $27bn “clean energy technology accelerator” to help deploy new renewable technology. A further $60bn would go towards environmental justice projects and there is a new program to reduce leaks of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from oil and gas drilling. Much of this is not direct public investment in climate projects but incentives to the private sector to do the right thing. The capitalist sector is being left to deliver on these targets.

And that’s the US. Elsewhere in the world, investment in meeting the already very modest target of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5C by 2030 is looking way too little. Indeed, the opposite is happening. For example, because of the threatened loss of energy in Europe from blocked Russian imports, the EU parliament has voted to designate gas and nuclear as sustainable! The need for energy to heat homes and fuel industry and transport after the Ukraine crisis has come into conflict with the aim to save the planet. The irony is that a global recession would reduce the demand for fossil fuel energy globally and so help reduce the impact on the planet.

And then there is the war itself. The military sector globally is the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in economies. And yet Nato’s secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg promised the alliance’s Madrid summit recently that there would be a nearly eightfold expansion in forces on high alert to 300,000. And member countries are also hiking defence spending to at least 2 per cent of GDP , “which is increasingly considered a floor, not a ceiling”. Russia’s military spending in 2021 hit $66bn, says the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. But even then, the US was spending $801bn a year and other Nato members about $363bn. NATO will be outspending Russia’s military by about 10 to one in the region, notes Dan Plesch of SOAS, University of London.

What the war and sky-high energy prices have brought home is that carbon pricing is no answer to controlling global warming. In effect, we’ve now got a global carbon tax, inflicting real hardship on people around the world without necessarily doing much to speed the transition from carbon.

I have argued against this ‘market solution’ in previous posts. Instead we need a global plan of public investment into things society does need, like renewable energy, organic farming, public transportation, public water systems, ecological remediation, public health, quality schools and other currently unmet needs. And it could equalize development the world over by shifting resources out of useless and harmful production in the North and into developing the South, building basic infrastructure, sanitation systems, public schools, health care. At the same time, a global plan could aim to provide equivalent jobs for workers displaced by the retrenchment or closure of unnecessary or harmful industries. None of those outcomes are offered by the IRA.

The other counter to the optimism now again coming forth on abating climate change and global warming is the risk of what is called in statistics a ‘fat tail’ in the probability of where global temperatures are likely to reach in the next few decades. The IPCC tends to look at the most probable outcome ie say a 2.5C increase by 2050. That’s bad enough. But there is still a reasonable probability that it could be much worse. Last year’s IPCC report suggested that if atmospheric CO doubles from pre-industrial levels – something the planet is halfway towards – then there is a roughly an 18% chance that temperatures will rise beyond 4.5°C. What would be the impact of that ‘fat tail’ coming through?

Well, just on GDP terms, one study shows that “a persistent increase in average global temperature by 0.04 °C per year, in the absence of mitigation policies, reduces world real GDP per capita by more than 7 percent by 2100. On the other hand, abiding by the Paris Agreement goals, thereby limiting the temperature increase to 0.01 °C per annum, reduces the loss substantially to about 1 percent.” The estimated losses would increase to 13 percent globally if country-specific variability of climate conditions were to rise commensurate with current annual temperature increases of 0.04 °C.

But that’s just the loss of GDP. The point is that if global temperatures were to reach above the optimistic 1.5C or 2.0C increase and beyond, the impact on the planet is exponential not gradual. “There are plenty of reasons to believe climate change could become catastrophic, even at modest levels of warming,” said lead author Dr Luke Kemp from Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, (https://www.cser.ac.uk/). Then what one study has called ‘the four horsemen of the climate apocalypse’ will appear, namely “famine and malnutrition, extreme weather, conflict, and vector-borne diseases.” The ‘fat tail’ of probability would deliver rising temperatures that pose a major threat to global food supply, with increasing probabilities of “breadbasket failures” as the world’s most agriculturally productive areas suffer collective meltdowns. Hotter and more extreme weather could also create conditions for new disease outbreaks as habitats for both people and wildlife shift and shrink.

The modelling in this study concluded that areas of extreme heat (i.e. an annual average temperature of over 29 °C), could cover two billion people by 2070. These areas are not only some of the most densely populated, but also some of the most politically fragile. “Average annual temperatures of 29 degrees currently affect around 30 million people in the Sahara and Gulf Coast,” said co-author Chi Xu of Nanjing University. “By 2070, these temperatures and the social and political consequences will directly affect two nuclear powers, and seven maximum containment laboratories housing the most dangerous pathogens. There is serious potential for disastrous knock-on effects,” he said.

The IRA may make some small inroads into emissions reduction in the US, if fully implemented (and as I say, there are serious doubts about that). But globally, there is little sign that global warming can be stopped at the Paris target; more likely global temperatures will rise above a 2C increase and beyond, as governments struggle to reconcile the need for energy at reasonable prices and reducing emissions (unless a major global slump solves the contradiction for a while). The four horsemen of the climate apocalypse are on the horizon.

July 31, 2022

Calling a recession and blaming it on interest rates

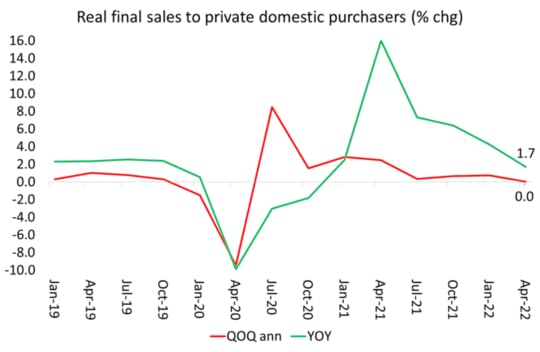

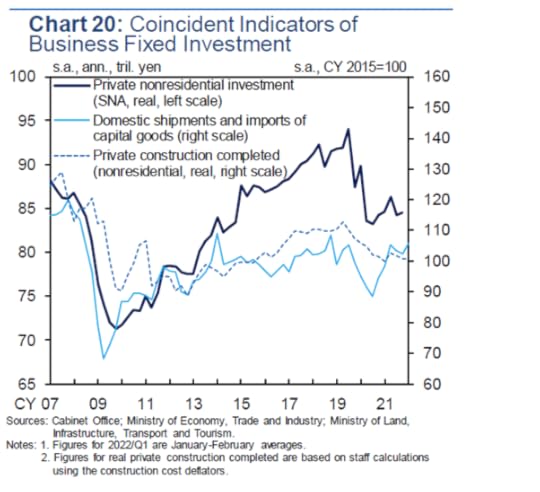

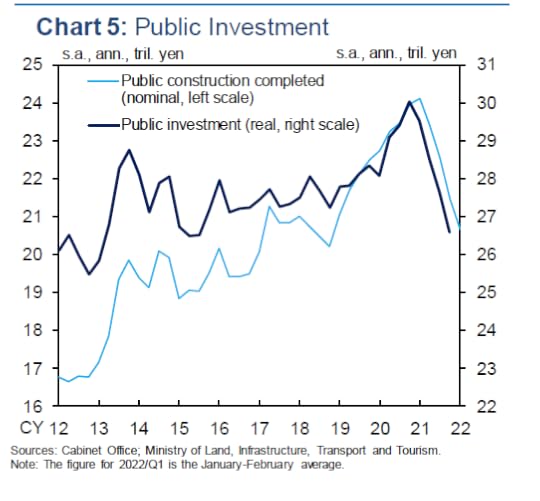

The latest US GDP figures for second quarter of 2022 renewed the debate about whether the US economy was in a recession or not. Real GDP contracted in the second quarter of this year by a 0.9% annualised rate (or by 0.2% quarter over quarter). That meant the US economy had contracted for two successive quarters, and so ‘technically’ (by that definition) was in a recession. Real GDP is now up only 1.6% from Q2 2021. And business investment is slowing, up only 3.5% from this time last year, the slowest rate since the end of the COVID slump in 2020.

But calling the US economy in ‘recession’ was denied by the powers that be, like President Biden, Fed chief Jay Powell and many mainstream economists who point out that unemployment is still near all-time lows and consumer spending is strong. Moreover, it is likely that this first estimate of GDP will be revised up – it usually is. Also, if you strip out the build-up of stocks and government spending from the GDP figures, then ‘core’ GDP did not fall in Q2. The best measure of this ‘core’ is the value of sales (after inflation) made to Americans ie real final sales to private domestic purchasers. On this measure, GDP was flat in Q2, while being still up 1.7% compared to Q2 2021.

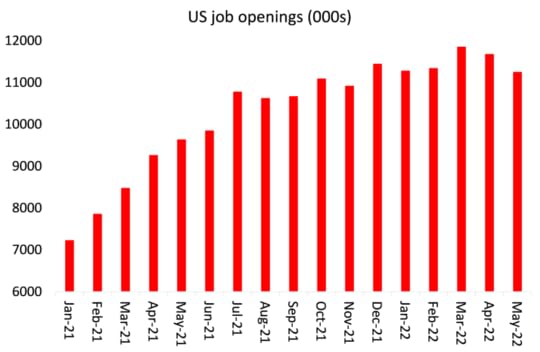

But even on this measure, the US economy is heading towards a recession, if not yet quite there now. But what about unemployment? is the response. That’s near all-time lows. But unemployment is a lagging indicator for the health of an economy. People start losing jobs only when employers stop hiring and start sacking and they don’t do that until they are sure that sales are dropping off, profits are no longer rising sufficiently or not at all; and then they cut back on investment in new factories, equipment etc. At the moment, the US employment data show only the beginnings of a weakening situation.

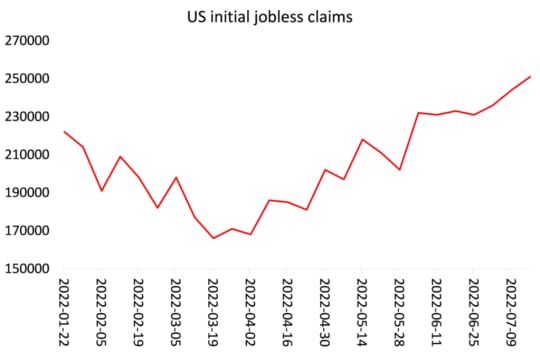

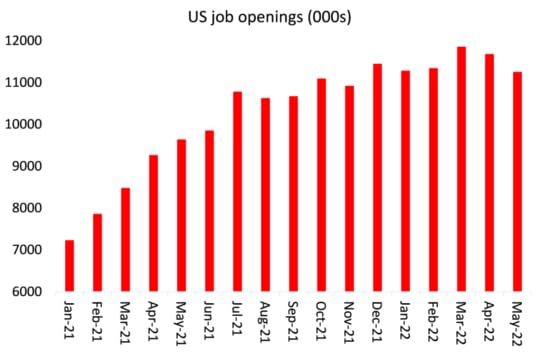

The initial jobless claims (the number of people claiming benefits because they are out of work) are now on a steady rise.

And the number of new jobs available (called JOLTS) have peaked.

So what are the leading indicators of a recession: in the Marxist view, it’s profits and investment. After reaching all-time highs, profit margins have begun to fall.

And nonresidential fixed (business) investment stagnated in Q2. The big hit was to house-buying (called residential fixed investment). Rising mortgage rates severely hit housing starts last quarter. So far real personal income ex-transfers and real personal consumption haven’t dropped, but they are stagnating. And wage income for the average American is diving in real terms as inflation spirals.

The powers that be say that you cannot call a recession unless the ‘wise men’ of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) do so and they have not yet. For some unfathomable reason, the NBER economists have become the arbiters of an official recession and they take into account, not just GDP, but also all the other factors mentioned above.

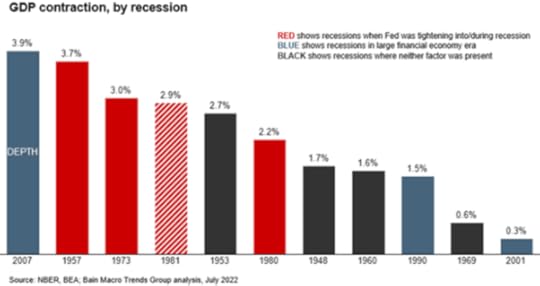

But the NBER always calls a recession in the long line of US recessions over the last century well after it has already happened. And it’s worth noting that US recessions have happened just when people claim they are not happening and, most important, whether the Federal Reserve is hiking interest rates or not. In 1957,1973 and 1980-2, recessions occurred when the Fed was raising rates, as it is now, but there were also recessions when it was not – as in 2007 before the Great Recession.

That poses the question of whether central banks have any significant effect on the economy either to sustain growth and employment and avoid slumps; or to control inflation. That question has been debated through two new books that have recently been published or are forthcoming. The first is by former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, who presided over the Great Recession of 2008-9. In it, Bernanke claims that the Fed saved the day in 2008-9 by pumping in credit for the banks and managed to keep inflation down as well. Bernanke argues that ‘quantitative easing’ (monetary injections and bond purchases by the Fed) did not cause inflation as many monetarists and Austrian school economists claimed it would. So central banks work. Of course, he does not explain why there was such a huge financial crash and the ensuing slump in 2008-9, despite the good ministry of the Fed. Apparently, that financial ‘panic’, as he calls it, was outside of the control of the central bank and can be blamed on lack of regulation.

At the other end of the spectrum, Austrian school economist, Edward Chancellor in his forthcoming book, The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest, presents the case for laying the cause of crises and slumps fairly at the door of the Fed and in the case of the Great Recession, at Ben Bernanke himself. Chancellor says “under Bernanke the Fed made a deliberate decision to ignore asset bubbles until they popped, seeing its job as simply repairing the damage. The housing bubble did indeed pop, causing quite a bit more damage than the Fed seemed to expect. The Fed under Greenspan and Bernanke forgot (or ignored) lessons stretching back to Bagehot in 19 th -century England.”

The Austrian school start from the premise that the ‘market economy’ works just fine and will deliver a natural or neutral rate of interest that will balance supply and demand. So things will then move on smoothly. Occasionally, because of the uncertainty of making investments for the long term, interest rates will get out of line with investment needs, and there will be ‘malinvestment’, usually leading to either a slump or inflation. These ‘business cycles’ will correct themselves, however, with a dose of unemployment and the liquidation of unproductive assets. But when central banks interfere to try and control interest rates, they distort them from the ‘natural’ rate’ and just make things worse and provoke unnecessary ‘credit bubbles’ which can only be burst with severe damage to the otherwise perfectly working market economy.

So for Bernanke, the issue is getting interest rates right to manage the economy; for Chancellor, it is stopping central banks interfering with interest rates and allowing the market economy to work. From a Marxist view, both the semi-Keynesian Bernanke and the neoclassical Austrian school Chancellor are wrong because they look only at interest rates and not at the real determinant of the capitalist economy, profits and profitability. The latter affects investment and growth much more than interest rates on borrowing.

A central bank controls only a component of the interest rate that helps determine the spread at which banks can lend, but it does not determine the rates at which banks lend to customers. It merely influences the spread. Aiming at the Fed’s supposed “control” over interest rates misunderstands how banks actually create money and influence economic output.

Marx denied the concept of a natural rate of interest. For him, the return on capital, whether exhibited in the interest earned on lending money, or dividends from holding shares, or rents from owning property, came from the surplus-value appropriated from the labour of the working class and appropriated by the productive sectors of capital. Interest was only a part of that surplus value. The rate of interest would thus fluctuate between zero and the average rate of profit from capitalist production in an economy. In boom times, it would move towards the average rate of profit and in slumps it would fall towards zero. But the decisive driver of investment would be profitability, not the interest rate. If profitability was low, then holders of money would increasingly hoard money or speculate in financial assets rather than invest in productive ones.

What matters is not whether the market rate of interest is above or below some ‘natural’ rate, as the Austrians claim, but whether it is so high that it is squeezing any profit for investment in productive assets. Actually, the Austrian, Knut Wicksell conceded this point. According to Wicksell, the natural rate is “never high or low in itself, but only in relation to the profit which people can make with the money in their hands, and this, of course, varies. In good times, when trade is brisk, the rate of profit is high, and, what is of great consequence, is generally expected to remain high; in periods of depression it is low, and expected to remain low.”

And the empirical evidence refutes the claim by both Bernanke and Chancellor that the setting of interest rates is key, not profits. Indeed, the US Fed itself concluded in its own recent study that: “A fundamental tenet of investment theory and the traditional theory of monetary policy transmission is that investment expenditures by businesses are negatively affected by interest rates. Yet, a large body of empirical research offer mixed evidence, at best, for a substantial interest-rate effect on investment…., we find that most firms claim to be quite insensitive to decreases in interest rates, and only mildly more responsive to interest rate increases.” But they are not insensitive to the profitability of their investments.

The US economy is moving into recession because profitability is falling and productive investment is stagnating. Of course, the economy is not helped by the Fed hiking rates at the same time, but if profits and investment were doing well, interest rates could rise without damage to the economy.

It’s the same story with longer-term economic growth. The key to sustained long-term real GDP growth is high and rising productivity of labour. Productivity growth has been slowing towards zero in the major economies for over two decades and particularly in the Long Depression since 2010. US labour productivity is currently falling and at its weakest for 40 years.

In his book, Chancellor claims that this weak productivity is due to central bank interference. He explained why in the interview last week. “By aggressively pursuing an inflation target of 2% and constantly living in horror of even the mildest form of deflation, they not only gave us the ultra-low interest rates with their unintended consequences in terms of the Everything Bubble. They also facilitated a misallocation of capital of epic proportions, they created an over-financialization of the economy and a rise in indebtedness. Putting all this together, they created and abetted an environment of low productivity growth.”

According to Chancellor, ultra low interest rates led to ‘malinvestment’ and thus low productivity. It’s true that much of the investment made in the last 20 years has gone not into productive sectors and instead has been moved into financial assets, leading to stock and bond market ‘bubbles’. But surely the reason for that is not artificially low interest rates, but low profitability on productive investment, now near all-time post-1945 lows along with productivity growth.

July 24, 2022

Europe: caught in a trap

The major economies are moving closer to recession, if they are not already there; and yet inflation rates continue to rise (for now). The latest surveys of business activity, called Purchasing Managers Indexes (PMIs), show that both the Euro area and the US are now in contraction territory (i.e. any level below 50). The composite PMIs (which put together both manufacturing and services) for the major economies in July show:

US 47.5 (contraction)

Eurozone 49.4 (contraction)

Japan 50.6 (slowing expansion)

Germany 48.0 (contraction)

UK 52.8 (slowing expansion)

Nobody should be surprised by the Eurozone score, given the impact of sanctions on Russian energy imports, which is severely weakening industrial production in the core of Europe (see below). Germany’s industrial production has been contracting for over three months.

The big shock was in the US. The US composite PMI also fell into contraction territory at 47.5 in July, down sharply from 52.3 in June to signal a solid fall in private sector output. The rate of decline was the sharpest since the initial stages of the pandemic in May 2020, as both manufacturers and service providers reported subdued demand conditions. So just as we enter the second half of 2022, US business activity is diving.

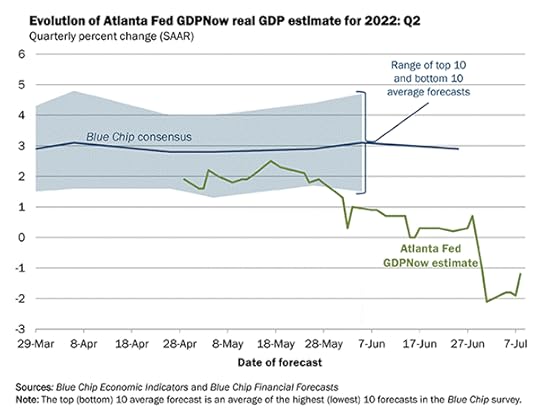

And according to the latest estimate of real GDP growth by the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank GDP NOW model, in the three months to June, the US economy contracted at a -1.6% annualized rate, matching a similar fall of -1.6% in the first quarter. If this estimate is confirmed next week, it would mean that the US was technically in recession.

The current response to this claim is: how can the US economy be in recession or close to it, when the unemployment rate is near all-time lows and payrolls keep on rising? But this response is dubious to say the least. First, there are two measures of employment for the US: the payroll figures and the household survey (a survey of households with jobs). The latter is currently showing the opposite of the former, namely a fall in the number of Americans at work. On this household measure, the labor force shrank, declining from 164.376 million to 164.023 million, and the participation rate (those in work compared to the total working age population) dropped more than expected to 62.2% – graph below.

Also, the initial jobless claims (the number of people claiming benefits because they are out of work) are now on a steady rise.

And the number of new jobs available (called JOLTS) have peaked.

Second, and most important, unemployment is a lagging indicator in a recession. The leading indicator is the movement in corporate profits and business investment, followed by production and then unemployment. Employment comes last because it rises only when corporations stop taking on more labour and begin to reduce their workforce. And they only do this when profitability and production start to fall away. And, after reaching all-time highs, profit margins have begun to fall.

During the COVID slump, profits rose sharply compared to wages and acted as the driver and gainer in rising inflation. Now that is beginning to change as profits are squeezed by rising components costs and weakening demand.

But it is in Europe that the evidence for an outright slump is most convincing. And it’s not just the data on economic growth that support that. In addition, Europe faces a huge squeeze on energy production and imports as the sanctions being applied on Russian gas and oil imports will not be sufficiently compensated for by imports from elsewhere.

Many German manufacturers are warning that they will have to close down production completely if energy inputs dry up. Petr Cingr, the chief executive of Germany’s largest ammonia producing company, and a key supplier of fertilisers and exhaust fluids for diesel engines, warned of the devastating consequences of the ending of Russian gas supplies. “We have to stop [production] immediately,” he said, “from 100 to zero.” According to UBS analysts, no gas for the winter will result in a “deep recession” with GDP contracting 6 percent by the end of next year. Germany’s Bundesbank has warned that the effects on global supply chains of any Russian cut-off would increase the original shock effect by two and a half times. ThyssenKrupp, Germany’s largest steelmaker, has said that without natural gas to run its furnaces “shutdowns and technical damage to our facilities cannot be ruled out.”

And it’s worse. Inflation is still rising in most European economies. So the European Central Bank (ECB) has decided that it must act to raise interest rates sharply. It pushed up its policy rate by 50bp last week, more than expected, taking the rate into positive territory for the first time in a decade. The days of ‘quantitative easing’ have been replaced by ‘quantitative tightening’.

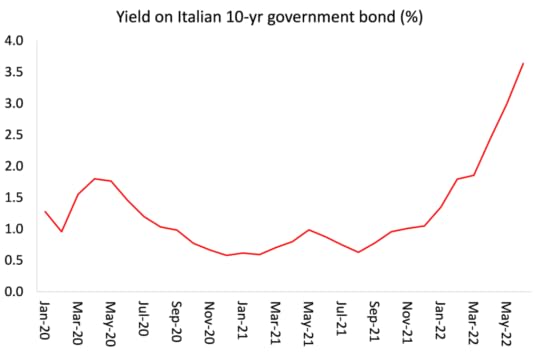

But this move comes at the worst time for countries like Italy, highly dependent on Russian energy. Last week, the technocrat former ECB chair, Italian prime minister Mario Draghi was forced to resign when several parties in his coalition government withdrew their support; some because they opposed his support for military aid to Ukraine; and some because they saw their chance to win an election. Italy has a very large public debt ratio to its GDP.

Up to now, the interest costs of servicing that debt have been low because interest rates have been kept low by the ECB, which has also provided billions of credit to Eurozone governments. But now interest rates are on the rise and investors in Italian government bonds have become worried that Italy (especially one without a viable government) may find it difficult to service these debts. So the yield on the Italian 10-year bonds surged to above 3.5%. The fall of the Italian government also threatens the distribution of billions of euros from EU Covid recovery funds, supposedly going to Italy next year to boost its economic growth.

So Europe’s economy is going down just as the ECB hikes rates to control inflation. As I have explained in previous posts, raising interest rates to control rising inflation caused by weak supply and productivity and the Ukraine war will not work, except to provoke a slump.

The ECB has now resorted to a desperate measure in introducing a transmission protection instrument (TPI), a new form of credit that will be doled out to governments like Italy if their bond prices collapse. However, this may never be used because it would mean the ECB would be providing open-ended financing of Italy’s fiscal spending, something likely to be against all the ‘Maastricht’ rules for the Eurozone.

The ECB is caught in what one analyst called a “nightmare scenario”. The deputy head of the Brussels-based Bruegel economic think tank, Maria Demertzis said, “The risk ahead of us is that because of the energy crisis, the euro area could end up in recession, while at the same time the ECB will have to keep raising rates if inflation does not come down.” Krishna Guha, head of policy and central bank strategy at US investment bank Evercore, said: “The combination of a brewing giant stagflationary shock from weaponised Russian natural gas and a political crisis in Italy is about as close to a perfect storm as can be imagined for the ECB.”

July 21, 2022

Is China headed for a crash?

Once again, Western ‘experts’ are predicting a financial crash in China. “China is flailing”, says one commentator; another says “a debt bomb is about to explode”. These would-be Cassandras reckon China’s demise will be driven by the bursting of the property bubble, excessive debt and the grinding down of the economy due to the government’s “terrible” ‘zero-COVID’ policy that keeps parts of the country in permanent lockdowns. And then of course, there are the growing restrictions on China’s exports and its investments abroad, imposed by the US and supposedly backed by its allies in Asia.

How much truth is there in this latest batch of critiques on China’s economic progress? The property crisis has reached dangerous levels. Last year, Evergrande, China’s second-largest private property developer was close to bankruptcy. The Evergrande property model is essentially a Ponzi scheme, where the company collects cash from the pre-sale of an ever-growing number of apartments, plus hundreds of thousands of individual investors and uses the cash to fund further sales by accelerating construction in progress and funding down-payments. Like any Ponzi, this works as long as it’s accelerating. But when the market slows, those incoming streams of cash start to fall behind the growing arc of cash demands. Evergrande now has about 800 unfinished projects and there are about 1.2 million people waiting to move in.

Now the property crisis has reached the point where millions of Chinese purchasers have stopped paying their upfront mortgage payments. Chinese homebuyers’ rapidly escalating boycotts on mortgage payments have spread across at least 301 projects in about 91 cities, with the value of mortgages that could be affected swelling to an estimated 2 trillion yuan ($297 billion). About 70% of household wealth in China is invested in real estate. Some Chinese banks have responded by seizing purchasers’ savings deposits, claiming they are really ‘mortgage investment products’. This has sparked open protests outside some banks, leading to the government surrounding the banks with tanks.

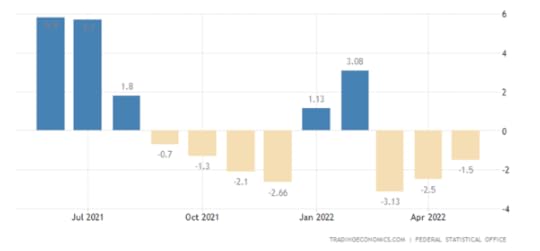

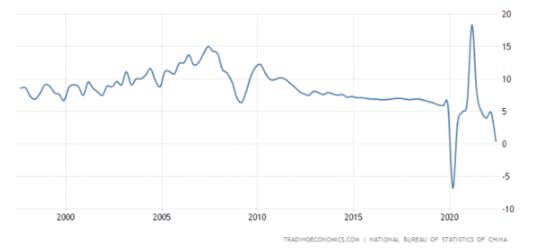

At the same time, China’s usually stupendous annual growth in real GDP has been sliding, even before the COVID slump in 2020. While recovery was strong in 2021, new bouts of COVID variants have caused new lockdowns. The Chinese government has been hugely successful in its policy of zero COVID, keeping the death rate down to miniscule levels compared with the major capitalist economies. But economic growth and employment have taken a hit as a result.

The Chinese economy shrank by a seasonally adjusted 2.6% quarter on quarter in the three months to June 2022. The nationwide urban survey-based unemployment rate eased only to 5.9% in May, with the unemployment rate for the 16-24 age group rising to an elevated 18.4%. It is increasingly clear that the government’s target real GDP growth rate of 5%-plus is not going to be met this year. And remember this target has been reduced over the last few years, as the double-digit annual expansion of the last decade has disappeared.

China: annual growth rate %

So, is this the moment of collapse in the Chinese model of development and the end of all that talk about ‘moving towards socialism’ etc? Many Western experts think so. What will cause this collapse, in their view, is the failure of the Chinese leaders to ‘liberalise’ the economy and open it up even more to capitalist companies and markets. Time to stop ‘zero COVID’ and relax restrictions as ‘successfully done’ (sic!) in the West. In effect, China needs more capitalism. It needs to expand the private sector.

But wait a moment. What are the causes of the current property crisis and the debt expansion? It can be laid squarely at the door of China’s expanding private sector, as promoted by a sizeable section of the Chinese leadership, particularly in the finance and property sectors.

Increasingly, China’s investment expansion has been in unproductive sectors like finance and real estate. Why in China, of all countries, was home building in the burgeoning cities left to private capital developers offering mortgages to buy? Why were homes not built by the state sector for rent? The result has been a classic case of a Western property market crash that the state now has to clear up. This will have to be resolved by the state (local governments) finishing off projects and restoring the rights of mortgagees to their money.

There is not going to be a financial crash in China. That’s because the government controls the financial levers of power: the central bank, the big four state-owned commercial banks which are the largest banks in the world, and the so-called ‘bad banks’, which absorb bad loans, big asset managers, most of the largest companies. The government can order the big four banks to exchange defaulted loans for equity stakes and forget them. It can tell the central bank, the People’s Bank of China, to do whatever it takes. It can tell state-owned asset managers and pension funds to buy shares and bonds to prop up prices and to fund companies. It can tell the state bad banks to buy bad debt from commercial banks. It can get local governments to take up the property projects to completion. So a financial crisis is ruled out because the state controls the banking system.

But the current property mess is a signal that the Chinese economy is becoming more influenced by the chaos and vagaries of the profit-based sector. It is the private sector that has been doing badly during COVID and after. Just one small example: COVID lockdowns in Shanghai were out-sourced to the private sector with poor results; in Beijing, local government did the job directly with much more success.

Profits in the capitalist sector have been falling. Profits earned by China’s industrial firms increased only by 1% yoy to CNY 34.41 trillion in January-May 2022, slowing from a 3.5% rise in the prior period, as high raw material prices and supply chain disruptions due to COVID-19 curbs continued to squeeze margins and disrupted factory activity. Profits at state-owned industrial firms rose 9.8%; while those in the private sector fell 2.2%. Only the state sector is continuing to deliver. This is what happened in the global financial crisis of 2008-9, which China avoided by expanding state investment to replace a ‘flailing’ capitalist sector. What Xi and the Chinese leaders have called the “disorderly expansion of capital”.

The capitalist sector has been increasing its size and influence in China, alongside the slowdown in real GDP growth, investment and employment, even under Xi. A recent study found that China’s private sector has grown not only in absolute terms but also as a proportion of the country’s largest companies, as measured by revenue or (for listed ones) by market value, from a very low level when President Xi was confirmed as the next top leader in 2010 to a significant share today. SOEs still dominate among the largest companies by revenue, but their preeminence is eroding.

Far from the answer to China’s mini-crisis requiring more ‘liberalising’ reforms towards capitalism, China needs to reverse the expansion of the private sector and introduce more effective plans for state investment, but this time with the democratic participation of the Chinese people in the process; not by tanks outside banks. Otherwise, the aims of the leadership for ‘common prosperity’ will be just talk.

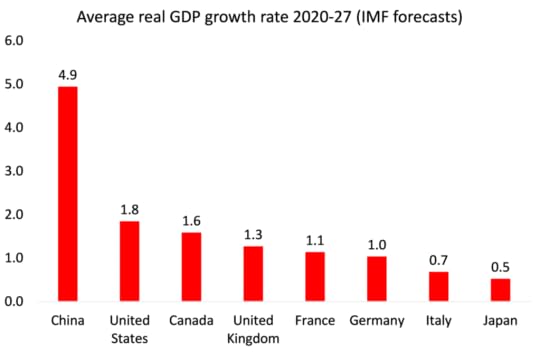

Having said all this, it is still the case that the public sector-dominated Chinese economy is and will do better than those in the West, the G7 economies. Here are the latest IMF forecasts for growth in the major economies.

Even this year, if China only manages around 4% real GDP growth, that would still be faster than any growth rate in the G7 economies. And the IMF forecasts that China will grow at 5%-plus in 2023, while G7 economies will be lucky to manage half that rate, assuming there is no new global slump. Indeed, longer term, the IMF forecasts that China will grow at a subdued rate of 5% a year, but that rate would more than twice as fast as the US, and more than four times as fast as the rest of the G7.

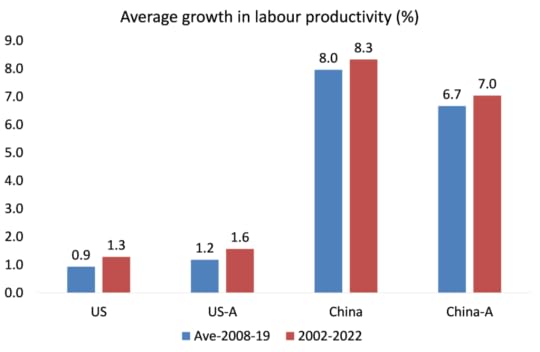

I have discussed at length in previous posts the claim by Western experts that China’s falling working-age population and its slowing productivity growth rate mean that it will begin to fail. These arguments are weak and faulty. Indeed, even on the adjusted (A) Western measures of labour productivity growth during the COVID period, China did way better than the ‘dynamic’ USA.

Indeed, the forecasts (and hopes) of the Western experts that China is about to melt down are clearly not agreed with by the strategists of capital in the US and NATO. They do not expect internal disintegration and so continue to try and strangle China’s economy externally.

July 13, 2022

Energy: the recession trigger?

There is confusion among mainstream economists and policy-makers on whether the major economies are heading for a recession, or are already in a recession; or will avoid one altogether. The majority view, at least in the US, is the latter. This optimistic view argues that, while inflation rates are high, they will start to fall over the next year, enabling the Federal Reserve to avoid hiking its policy interest rates too much to the point where it could restrict investment and spending. At the same time, the US unemployment rate is very low and the ‘labour market’ remains strong. Such a scenario hardly suggests a recession. Who ever heard of a slump where there is full employment?, the argument goes.

On the other hand, the pessimistic view is that the major economies are already in a slump that will be eventually recognized. If we look at the models that measure various aspects of economic activity, the major G7 economies seem to have contracted in Q2 of this year. The Atlanta Fed Now model puts US GDP contracting by an annual rate of 1.2%.

And the Euro-Area weekly tracker also suggesting contraction of about annual rate of 1% there.

Is it possible to have a recession and a tight labour market at the same time? US real GDP fell at a -1.5% annual rate in Q1 and looks like repeating that in Q2. That’s a ‘technical recession’, as it is called. But the unemployment rate is 3.6% near record lows and 380,000 jobs are being created each month, on average, over the past four months.

The extremely well-paid economists of the investment bank, Goldman Sachs, try to reconcile these divergent indicators. It’s true, they argue, that some GDP tracking estimates now project negative Q2 GDP growth, which would trip the rule of thumb that two quarters of negative growth constitute a recession. But they point out that the indicators on employment, real personal income less transfers, and gross domestic income have all continued to increase. And they find it “historically unusual for the labor market to be as strong as it is at present even at the very outset of a recession. In particular, nonfarm payroll employment has grown at roughly double the typical pace at the start of past recessions.” Nonfarm payrolls have grown at an annualized pace of 3.0% over the last three months and 3.7% over the last six, roughly double the typical pace at the start of past recessions.

But Jan Hatzius, chief US economist at Goldman Sachs, said there is “no doubt that a labour market slowdown is under way”, adding that “job openings and quits are declining, jobless claims are rising, the ISM employment indices in manufacturing and services have fallen to contractionary levels, and many publicly traded companies have announced hiring freezes or slowdowns”. That suggests that unemployment is a lagging indicator in judging when a slump comes. Indeed, that would be in line with a Marxist analysis of slumps. First, profitability declines, particularly in the productive sector, then profits in total. This leads to a fall in investment by companies and then the laying off of labour and a reduction in wages.

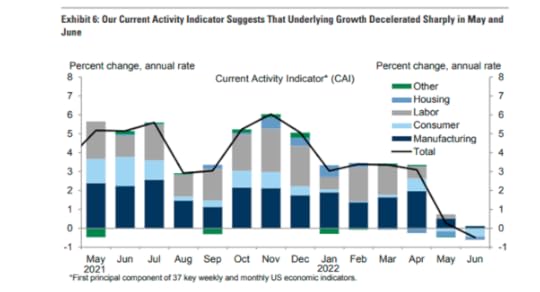

The GS economists admit that the battery of economic indicators that they look at are now suggesting the negative in the latest months.

GS concludes that there is a 30% probability of entering a recession over the next year, but a 48% probability of entering a recession by next year – in other words, it’s more or less likely by 2023, but not yet. For them, “we do not have a recession in our baseline forecast, but we continue to expect well below consensus growth and do see heightened recession risk.”

As I have referred to in several previous posts, if the government bond ‘yield curve’ inverts, it is a relatively reliable indicator of a future recession. The ‘yield curve’ measures the difference between the interest rate earned on a government bond that has, say, a ten year life or maturity and the interest rate on a bond of say just three months or a year. Normally, somebody who invests in a longer term bond expects a higher interest rate because their money won’t be paid back for a longer time. So the yield curve is usually positive ie the rate on the longer term bond is higher than on the short term bond. But sometimes it goes negative because bond investors are expecting a recession and so put their money into longer-term government bonds as the safest way to protect their money. So the yield curve ‘inverts’.

When that happens and the curve stays inverted, recession seems to follow within a year or so. The US government bond yield curve for 10yr-2yr is now inverted. The last time that happened was in 2019 when the major economies seemed to be heading for a slump anyway, just before the COVID pandemic.

The frightening thought for the US economy is that if inflation rates stay high and unemployment stays low, then it may take two recessions to kill inflation and smash jobs, the ultimate aim of the Fed and the authorities. That’s what happened between 1980-82 – a double-dip recession.

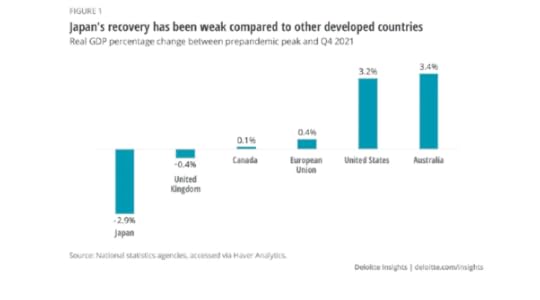

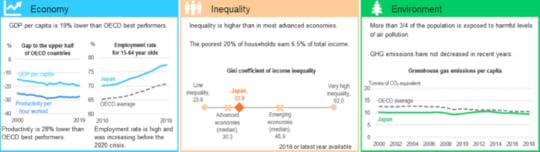

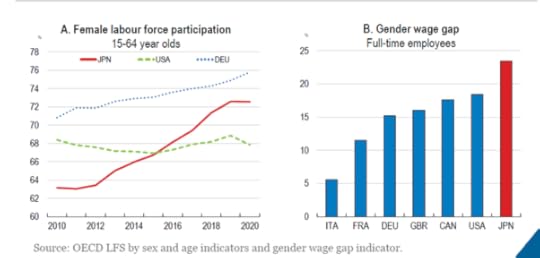

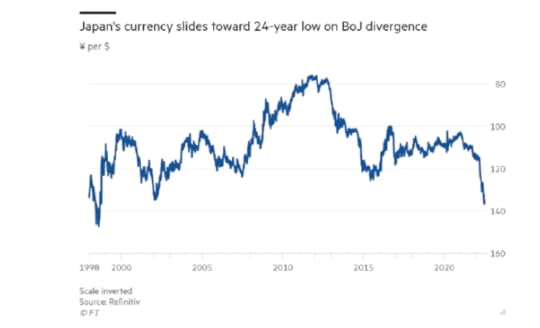

That’s the US economy, where the recovery from the COVID slump has been greatest among the major economies – although that is not saying too much. The situation is much worse in stagnant Japan (see my recent post) and in Europe where the Russia-Ukraine crisis portends a major energy crisis. Indeed, the war and the sanctions on Russia look like triggering a slump in the Eurozone of major proportions.

Already, Russian gas exports are down by one-third from a year ago and only 40% of the Nord Stream1 pipeline capacity is being used. As winter approaches, demand for gas in Europe will double, causing a serious shortfall for industrial production and heating homes. That alone could contract the Eurozone economy by 1.5-2.8% of GDP, according to some estimates. And rocketing natural gas and oil prices would drive up the inflation rate even more into double-digits by mid-winter.

The main pipeline for Russian gas to the EU through Ukraine is currently down for ten-day maintenance. But if Russia decides that it and the Nord Stream1 pipeline are not to be brought back online – fully or in part – things could get a lot worse.

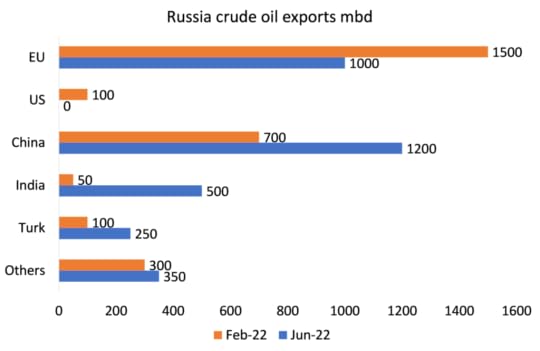

Russia now sells more oil than before it invaded Ukraine. So Russia’s current account surplus is likely to be over $160bn (more than 3.5 times the previous year), with more oil sold to China and India to compensate for the drop to Europe.

But what could trigger an even a deeper recession in Europe and globally would be if the G7/NATO countries go ahead with their plan to introduce price caps on Russian oil. The only way the G7 sees how to bring down oil prices and deprive Russia of oil revenues to finance its war is to price cap Russian oil. The cap would presumably be set between the cost of producing Urals (say $40/bbl) and its current discounted sale price of $80/bbl.

This plan is not going to work, however. Countries like India, China, Indonesia and a raft of others are not going to join a cartel that punishes themselves whether they like Russia or not. Given that the supply and demand balance in global oil markets is very tight, knocking out whole or part of Russian output will raise global prices sharply. And Russia could well retaliate by halting all oil exports to either the EU or all participants in the cap scheme. Moreover, the scheme of using shipping insurance to enforce the cap on Russian cargoes will mean that both Russia and some consuming states will set up their own state-sponsored insurance schemes (as China did with Iran and as the Russian National Reinsurance Company is doing for Russian shipping now).

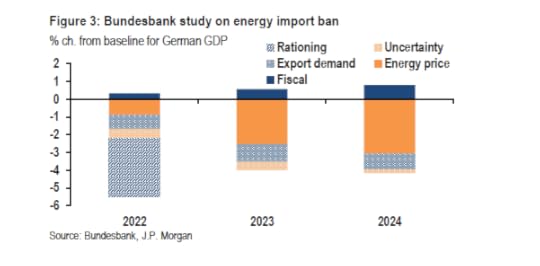

Far from forcing Russia to submit to NATO demands, any oil price cap is more likely to drive the oil price to near $200/bbl. That would trigger a global slump. The German central bank, the Bundesbank, reckons that real GDP in Germany could plunge as much 4-5% pts from its previous growth rate.

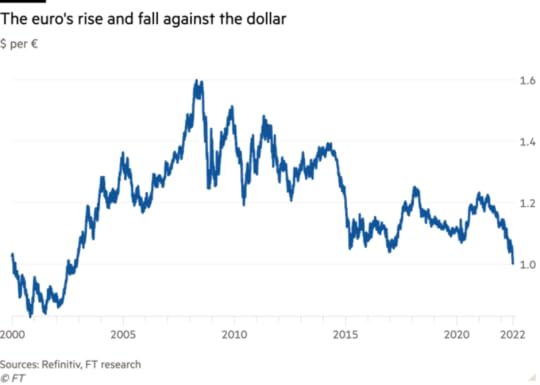

No wonder the euro has dropped to near parity with the US dollar in foreign currency markets, its lowest level since 2002.